SUMMARY

Progressive organ fibrosis accounts for one-third of all deaths worldwide, yet preclinical models that mimic the complex, progressive nature of the disease are lacking, and hence, there are no curative therapies. Progressive fibrosis across organs shares common cellular and molecular pathways involving chronic injury, inflammation, and aberrant repair resulting in deposition of extracellular matrix, organ remodeling, and ultimately organ failure. We describe the generation and characterization of an in vitro progressive fibrosis model that uses cell types derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. Our model produces endogenous activated transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and contains activated fibroblastic aggregates that progressively increase in size and stiffness with activation of known fibrotic molecular and cellular changes. We used this model as a phenotypic drug discovery platform for modulators of fibrosis. We validated this platform by identifying a compound that promotes resolution of fibrosis in in vivo and ex vivo models of ocular and lung fibrosis.

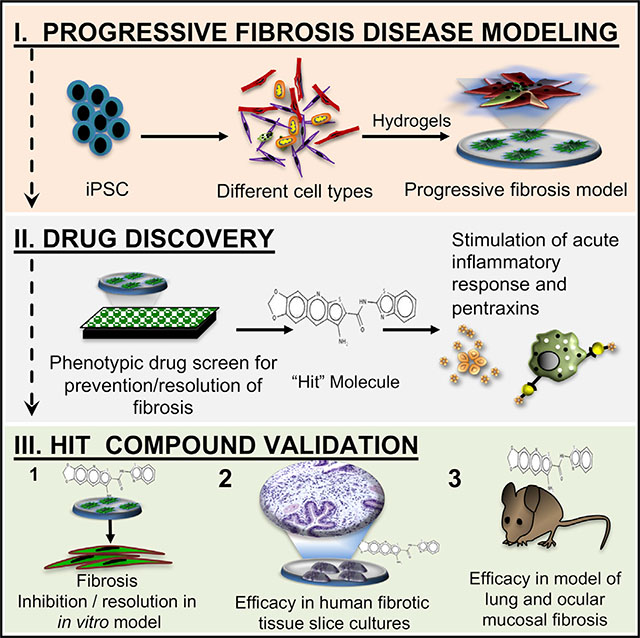

In Brief

Vijayaraj et al. describe the generation and characterization of an in vitro progressive fibrosis model that is broadly applicable to progressive organ fibrosis. They use it to identify a promising anti-fibrotic therapy that acts by activating normal tissue repair.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Our capacity to heal injured tissue is critically important for survival (Das et al., 2015). However, chronic, ongoing injury in any organ with failure to heal can result in tissue fibrosis (Martin and Leibovich, 2005). Fibrosis is characterized by overexpression of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) family members and the abnormal and excessive buildup of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, such as fibrillar collagen (Nanthakumar et al., 2015; Zeisberg and Kalluri, 2013). This accumulation of ECM triggers progressive organ remodeling and therefore organ dysfunction. Often, this fibrotic process is driven by metabolic and inflammatory diseases that result in organ injury and perpetuate the fibrosis (Martin and Leibovich, 2005; Wynn and Ramalingam, 2012). At early stages, the fibrosis is thought to be reversible, but upon progression, it can result in end organ failure (Wynn and Ramalingam, 2012). The fact that many different diseases all result in the same fibrotic response in different organs such as the liver, kidney, lung, and skin speaks for a common disease pathogenesis (Rockey et al., 2015; Zeisberg and Kalluri, 2013). Although we understand many of the molecular and cellular pathways underlying wound healing and fibrosis, we lack relevant human models of progressive fibrosis, mainly due to the challenges in reproducing persistent inflammation and cellular plasticity that precedes tissue remodeling and fibrosis (Meng et al., 2014; Nanthakumar et al., 2015; Pellicoro et al., 2014; Tashiro et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2010). Here, we report an in vitro human model that recapitulates the common inflammation-driven progressive fibrosis seen across organs. The unique response of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) differentiated to multiple different cell types and cultured on a stiff polyacrylamide hydrogel reproduces the molecular and cellular pathways found in progressive fibrotic disorders. This model of progressive fibrosis is amenable to drug screening and allowed us to identify a compound with promising anti-fibrotic potential.

RESULTS

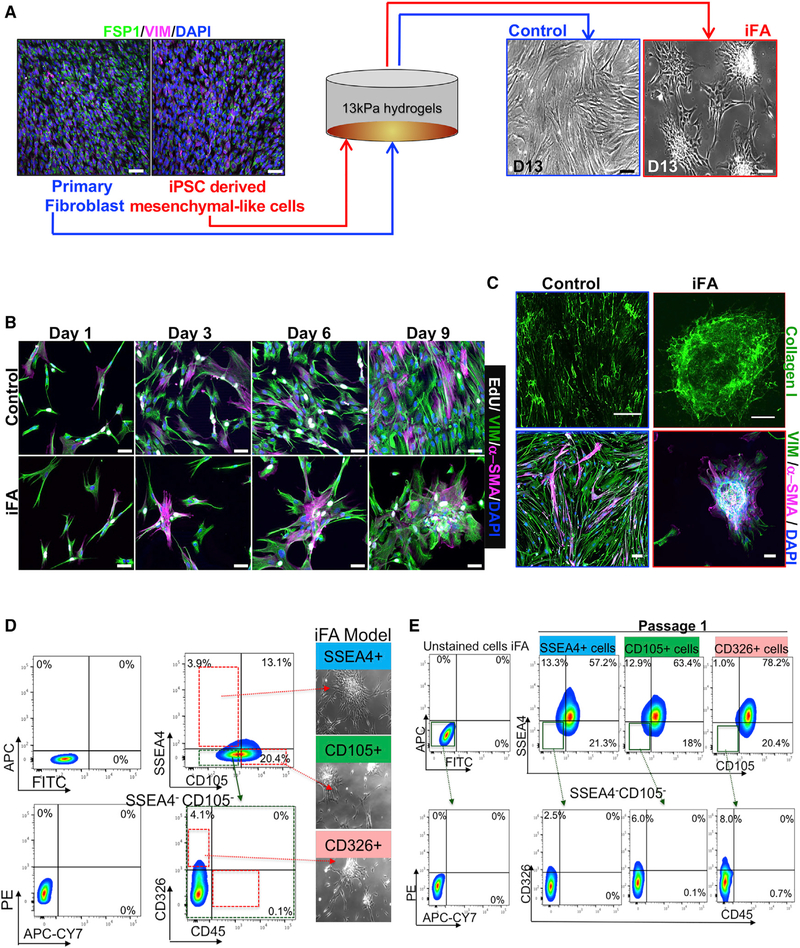

Differentiation of iPSCs to Multiple Cell Types for Disease Modeling

iPSC technology is an attractive tool to model and study complex diseases. Progressive fibrosis is one such complex disease that can occur in any organ and arises from the cumulative effect of aberrant wound repair involving multiple cell types, including fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and immune cells responding to various mechanical and chemical stimuli. Our scientific rationale for using iPSCs to model fibrosis in vitro was inspired by published studies of other complex diseases, namely Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, where fibrillary tangles and senile plaques were modeled in a dish (Tong et al., 2017). Given the promise of iPSCs for disease modeling and drug discovery and the extremely limited therapies available for progressive fibrosis, we undertook the task of using iPSCs to model the complex phenotype of progressive fibrosis that could lend itself to drug discovery. Every tissue in our body is capable of a wound-healing response that involves a scarring phase (Stroncek and Reichert, 2008). Additionally, reprogramming human somatic cells to iPSCs from any source and disease state leads to erasure of the existing somatic epigenetic memory (Nashun et al., 2015). Hence, we used iPSCs reprogrammed from different sources such as dermal and lung fibroblasts and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and differentiated them into multiple different cell types critical for modeling fibrosis (Guzzo et al., 2013; Manuilova et al., 2001; Murray, 2016; Passier et al., 2016) (Figures S1A–S1H; Table S1). The differentiated cells were composed of over 90% mesenchymal-like cells, as determined by their morphology in cell culture and expression of mesenchymal markers such as vimentin (VIM) and SSEA4 (Figures S1C and S1D). The mesenchymal-like cells lacked pluripotency markers such as TRA-160 and OCT4 (Figures S1C and S1E) and showed high expression of the mesenchymal stem cell markers CD73, CD90, and CD105 (Figure S1E) We therefore henceforth refer to them as mesenchymal-like cells. Importantly, over 30% (60.5% ± 4.3 [mean ± SEM]) of the mesenchymal-like cells showed expression of SSEA4 (Figure S1D), a marker associated with a fibrosis-initiating cell population in lung (Xia et al., 2014) and oral submucosa (Yu et al., 2016). Furthermore, there was a subpopulation of mesenchymal-like cells that expressed the epithelial cell marker CD326 (6.7% ± 0.5 [mean ± SEM]) (Figures S1E and S1F). There was also a separate small population of cells (4.9% ± 0.64 [mean ± SEM]) that expressed the immune cell markers CD45, CD32, CD11b, CD68, or CD14 (Figures S1E, S1G, and S1H). Cells with the classic features of macrophages such as heterochromatin, vacuolated cytoplasm, microvilli, and whorls of phagocytosed matter were found in low numbers within the differentiated cells by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the cells in the cultures (Figure S1H).

iPSC-Derived Mesenchymal-like Cells Model Progressive Fibrosis

To model progressive fibrosis, we cultured the mesenchymal-like cells on polyacrylamide-based hydrogels at 13 kPa (Mih et al., 2011), a stiffness that approximates that of a fibrotic organ (Clarke et al., 2013; Lagares et al., 2017). Hydrogels were functionalized with benzoquinone (Kálmán et al., 1983) and coated with 0.1% gelatin. Our cellular controls for this model consisted of primary fibroblasts obtained from the same anatomical sites as the site from which the mesenchymal-like cells were derived (parent primary fibroblast) (Figure 1A). The mesenchymal-like cells and the parent primary fibroblasts expressed SSEA4 and CD44 (Figure S1I). However, the mesenchymal-like cells also expressed CD326 and CD45, which the parent primary fibroblasts lacked (Figure S1I).

Figure 1. Generation of the iFA Phenotypic Surrogate of Progressive Fibrosis.

(A) Comparative immunofluorescence (IF) images of primary fibroblasts and mesenchymal-like cell cultures stained for fibroblast (FSP-1) and mesenchymal (VIM) markers cultured on 13-kPa hydrogels. Phase contrast images show monolayer cultures of the primary fibroblasts grown on hydrogels while the mesenchymal-like cells heaped up as scar-like aggregates (also called induced fibroblast activation [iFA] cultures) as shown on day 13. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(B) Comparative IF images of primary fibroblasts and mesenchymal-like cell cultures on days 1, 3, 6, and 9 stained with α-SMA, vimentin (VIM), and EdU after a 6-h EdU treatment. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(C) Representative IF images of decellularized primary fibroblast (control) and iFA cultures stained for collagen I (top) and α-SMA (bottom). Scale bars, 50 μm.

(D) Single-positive cells for SSEA4, CD105, and CD326 (negative for CD45) were sorted from the iFA model and re-cultured on 13-kPa hydrogels (n = 3).

(E) The iFA model created from single-positive cells of CD105, SSEA4, and CD326 in (D) were individually reanalyzed using FACS.

During a 13-day culture period on 13-kPa hydrogels, the mesenchymal-like cells failed to form a monolayer like that of the primary fibroblasts cultured under the same condition. Instead, the mesenchymal-like cells were highly proliferative and formed a dense, progressively enlarging scar-like phenotype (Figures 1A, 1B, S1J, and S1K; Videos S1 and S2). While the primary fibroblasts contained fewer proliferating cells (~25%) following contact inhibition by day 9 of culture as observed from EdU labeling, the mesenchymal-like cells continued to proliferate as scar-like aggregates (Figures 1B and S1L). Consistently, these aggregates revealed increased gene expression and protein levels of collagen I, α-SMA, and TGF-β when compared to the primary fibroblasts cultured under the same conditions (Figures 1C and S1M–S1O). Thus, the cultured mesenchymal-like cells with the scar-like phenotype in our model share many of the characteristics of the induced fibroblast activation (iFA) phenotype that is classically seen in organ fibrosis (Kendall and Feghali-Bostwick, 2014; Kong et al., 2018; Shinde and Frangogiannis, 2017; Shinde et al., 2017; Zeisberg et al., 2000). The iFA phenotype was consistently observed in all mesenchymal-like differentiated cell cultures (n = 17 patient samples) (Table S1), while primary fibroblasts showed no fibroblast activation phenotype irrespective of the source of tissue from which they were isolated.

To understand what was unique about our mesenchymal-like cells, we profiled them further and found them to demonstrate plasticity; when cells from our iFA model were negatively selected for CD45 expression and sorted for single-positive populations of SSEA4+, CD326+, or CD105+ (an auxiliary receptor for the TGF-β receptor complex; Guerrero-Esteo et al., 2002) cells and replated onto the 13-kPa hydrogels, each single-positive population was able to generate the iFA phenotype within 13 days (Figure 1D). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis revealed that the single-positive populations were able to repopulate into all the other cell types (Figure 1E). The pathological effects of progressive fibrosis are associated with cell plasticity, which plays a major role in the phenotypic transitions in cell populations that contribute to tissue remodeling in organ fibrosis (Nieto, 2013; Varga and Greten, 2017). These phenotypic transitions are commonly seen as epithelial-to-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions (Fabregat and Caballero-Díaz, 2018; Stone et al., 2016). This suggests that in our model, the multipotent nature of the mesenchymal-like cells and their plasticity are key in modeling progressive fibrosis.

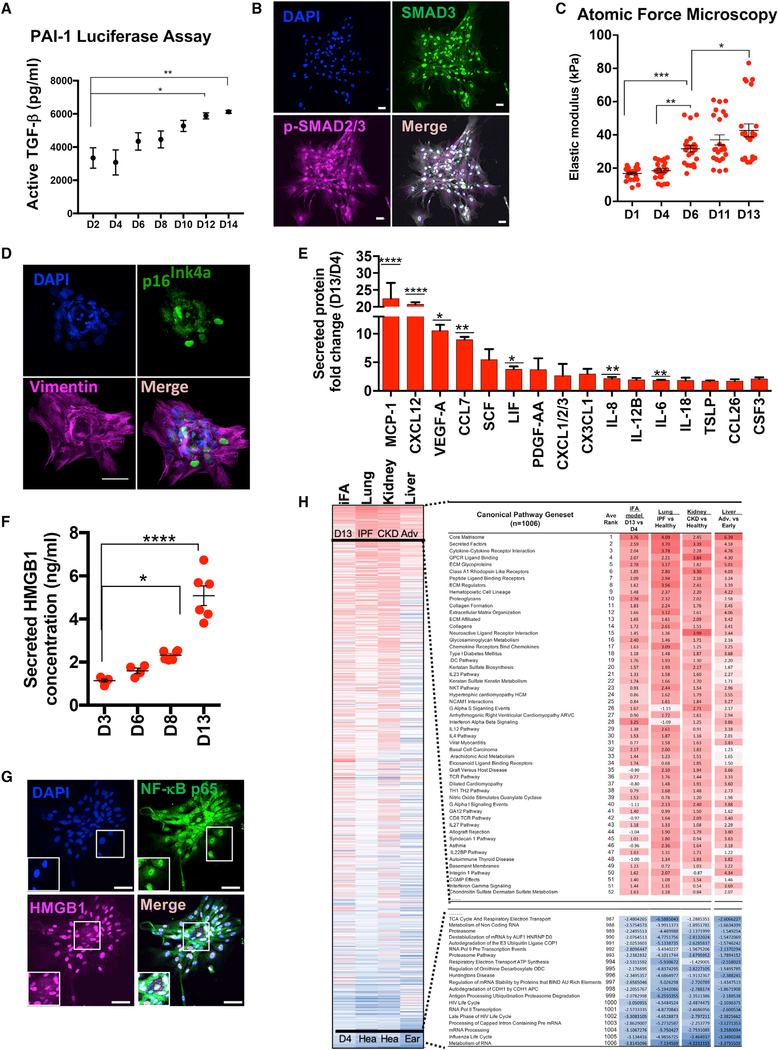

Characterizing the Induced Fibroblast Activation (iFA) Phenotypic Surrogate of Progressive Fibrosis

To validate how closely our iPSC-based iFA model recapitulates progressive fibrosis, we employed several assays to further characterize the model. First, we used mink lung epithelial cells (mLECs) that stably express luciferase under the control of the PAI-I (plasminogen activator inhibitor) promoter that is activated in the presence of TGF-β (Abe et al., 1994). mLECs were cultured in conditioned media collected from the iFA model at different time points (days 2–14). We observed increasing reporter activity over 13 days in culture as the iFA phenotype progressed, indicating that the iFA model produced increasing amounts of active TGF-β over time (Figures 2A and S2A). Additionally, culture supernatants from days 3, 7, and 13 showed increasing amounts of secreted TGF-β1 over time as the iFA phenotype progressed (Figure S2B). Consistently, in the iFA model at day 13, we observed activation of SMAD2/3, which are two major downstream regulators that promote TGF-β1-mediated tissue fibrosis (Figure 2B). Parenchymal stiffness increases as organ fibrosis progresses (Ben Amar and Bianca, 2016; Clarke et al., 2013; Wells, 2013). We used atomic force microscopy (AFM) to measure the local elastic response of the cell membranes and the underlying cytoskeleton resulting in stiffness in our iFA model. The elastic modulus was calculated by fitting force-indentation curves to the Sneddon contact model. The cells in the iFA model exhibited an elastic modulus ranging from 15 to 70 kPa, similar to that of fibrotic organs (Clarke et al., 2013; Lagares et al., 2017), and the stiffness increased with the progression of the iFA phenotype over time in culture (Figures 2C, S2C, and S2D). Senescent cells (20%–30%) were observed with p16INK4A staining in the iFA model during progression of the fibrotic phenotype, consistent with what has been described in fibrotic lung (Schafer et al., 2017), liver (Lasry and Ben-Neriah, 2015), and kidney tissue (Sturmlechner et al., 2017) (Figure 2D). Relative levels of cytokines and chemokines that are normally elevated in patients with fibrotic diseases (Borthwick et al., 2013; Hasegawa and Takehara, 2012) showed a similar profile in our disease model using a cytokine array, with notable increases in cytokines MCP-1, CXCL12, VEGF-A, interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and CSF3 (Figure 2E). These data suggest that there is a senescence-associated secretory phenotype in the iFA model. Using ELISA at different time points in our iFA model, we also observed increasing levels of secreted HMGB1 during progression of the phenotype (Figure 2F). The secretion and cytoplasmic translocation of nuclear HMGB1 can account for the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) (Kim et al., 2017; Li et al., 2016; López-Novoa and Nieto, 2009; Tadie et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2017) (Figure 2G) The activation of NF-κB in our iFA model is seen by its nuclear localization in the cells in our model (Figure 2G). As a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) protein, HMGB1 has been reported to be a pro-fibrotic agent in liver, renal, and lung fibrosis (Hamada et al., 2008; Li et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Characterization of the Induced Fibroblast Activation (iFA) Phenotypic Surrogate of Progressive Fibrosis.

(A) Active TGF-β secreted during the progression of the iFA phenotype (days 2–14) in a TGF-β bioassay (n = 3).

(B) Representative immunofluorescent image of iFA model stained for total SMAD3 and p-SMAD2/3 (S465/S467).

(C) Quantification of cell stiffness of the cells in the iFA model at different time points (days 1–13) (n = 22).

(D) Representative image of the iFA model at day 13 of culture stained with p16Ink4 staining and counterstained with VIM.

(E and F) Cytokine profiles (E) and HMGB1 (F) levels determined from conditioned media of the iFA model at day 13 relative to day 4 (n = 5 in duplicate).

(G) Representative image of the iFA model at day 13 stained for NF-κB p65. HMGB1 was translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm.

(H) Enrichment analysis of canonical pathways (1,006 MSigDB canonical pathways) in transcriptome data of RNA sequencing in day 13 versus day 4 cultures of the iFA model compared to the fibrotic organ versus healthy tissue data. Fibrotic organs include IPF versus healthy lung (n = 8), advanced (n = 6) versus early (n = 6) liver steatosis, and kidneys from chronic kidney disease (n = 46) versus healthy controls (n = 8). Related to Figure S2E and Table S1.

Scale bars, 50 mm. Data in figures represent the mean ± SEM; ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

We next performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to integrate the differential gene expression from RNA collected at day 4 (pre-iFA phenotype) and day 13 (established iFA phenotype) of the iFA model and to identify the top canonical pathways enriched during the progression of the iFA phenotype compared to published datasets from human healthy and fibrotic lung (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [IPF] [GEO: GSE52463]), human healthy and fibrotic kidney (chronic kidney disease [GEO: GSE66494]), and human early and advanced fibrotic liver (liver steatosis [ArrayExpress: E-MTAB-6863]) tissues (Nakagawa et al., 2015; Nance et al., 2014; Ramnath et al., 2018) (Figure 2H). The iFA model showed enrichment of genes encoding matrisome, ECM glycoproteins, chemokine-cytokine receptor interaction, proteoglycans, secreted factors, and the IL-4 pathway in a pattern similar to that seen in fibrotic lung (p = 0.018), kidney (p = 0.033), and liver (p = 0.089) tissues (Figure 2H; Table S2). Genes responsible for cell-surface interactions (e.g., integrin 1 pathway) and regulation of inflammatory host defenses, cell growth, and differentiation (e.g., cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions) were also enriched in the iFA model and across the fibrotic organ tissues (e.g., IPF [p < 0.01]) (Figure S2E). On the other hand, healthy human tissues of lung, liver, kidney, and pre-iFA phenotype cultures shared similar expression of genes associated with normal cell function, including DNA replication and cell cycle pathways (Figure 2H; Table S2). Taken together, this characterization of the iFA model revealed that it displays many gene expression profiles in common with fibrotic human tissues.

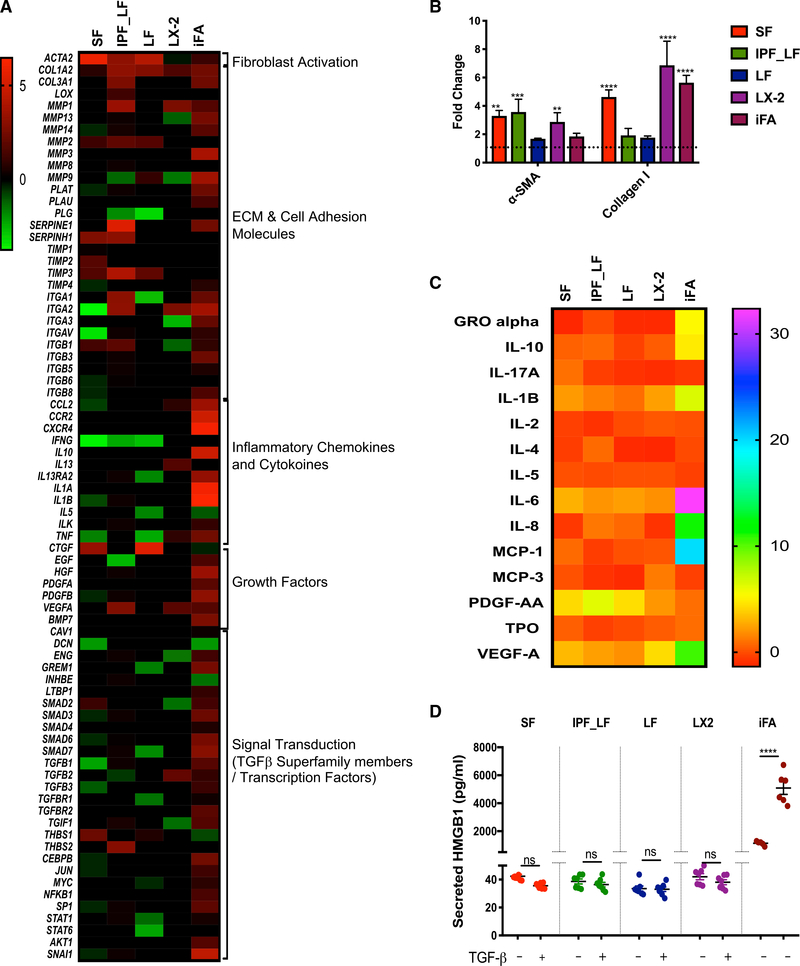

The iFA Model Is More Representative of Human Fibrotic Diseases than Exogenous TGF-β-Induced Fibrosis Models

To examine how our iFA model compares to the most commonly used fibrosis models in drug discovery programs, we performed a head-to-head comparison of our iFA model (that has no exogenous addition of TGF-β) to primary hepatic stellate cells (LX-2), primary fibroblasts from healthy (LF) and fibrotic lung (IPF_LF), and healthy skin (SF) that were exogenously treated with TGF-β for 48 h. The 48–72 h time frame of TGF-β treatment is the norm in the field of fibrosis drug discovery, since the cells reach the point of contact inhibition by this time. This comparison was first performed using a Human Fibrosis RT2 Profiler PCR Array to profile the expression of 84 key genes involved in dysregulated tissue remodeling during repair and regeneration. Consistent with the known pathogenesis of fibrosis, fibroblast activation (ACTA2) and ECM (COL1A2 and COL3A1) genes were upregulated in all models (Figure 3A). Interestingly, TGF-β was upregulated in the iFA model but downregulated in the models where TGF-β was given exogenously (Figure 3A). Increased fibroblast activation and ECM deposition across the models was also confirmed at the protein level by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence staining (Figures 3B, S3A, and S3B). However, the iFA model, unlike the other models, showed a strikingly higher inflammatory chemokine/cytokine, growth factor, and TGF-β superfamily involved signal transduction signature (p < 0.05) (Figure 3A). Next, we examined secreted levels of several cytokines/chemokines and the DAMP molecule HMGB1 across all fibrosis models. Consistent with what was observed at the gene expression level, we observed significant levels of secreted cytokines/chemokines such as IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and VEGF-A, and the DAMP molecule HMGB1 in our iFA model, whereas the primary fibroblasts that were exogenously treated with TGF-β did not show a significant increase in expression of these proteins after treatment (Figures 3C and 3D). Additionally, we stained all the models for β-galactosidase to identify senescent cells. While we saw progressively increasing numbers of senescent cells in our iFA model, we did not observe any senescent cells after 48-h treatment with TGF-β in the other models (Figure S3C), and these data were consistent with the lack of inflammatory signature seen across the TGF-β-induced fibrosis models (Figures 3A and 3C). This extensive characterization of our model and its comparison with exogenously added TGF-β-driven fibrosis models demonstrates a clinically relevant human model that phenotypically and functionally resembles inflammation-driven fibroblast activation and progressive fibrosis in a dish.

Figure 3. Direct Comparison between the iFA Model and TGF-β-Induced Fibrosis Models Commonly Used in Drug Discovery Programs.

(A) Heatmap summarizing fold change for 84 fibrosis-related genes exhibiting differential expression across the iFA model (day 13 versus day 4) and TGF-β-induced fibrosis models (TGF-β-treated versus untreated); SF, skin fibroblasts; LF, normal lung fibroblasts; IPF-LF, IPF lung fibroblasts; LX-2, hepatic stellate cell line. Heatmaps show log-base-2-transformed data for each experiment mean expression (n = 3) of genes with p value < 0.05 in at least one of the samples per gene.

(B) Densitometric analysis depicting fold change of α-SMA and collagen I in fibrosis models (TGF-β-treated versus untreated) and the iFA model (day 13 versus day 4) analyzed by immunoblotting normalized to total protein (for α-SMA) or β-actin (for collagen I).

(C) Heatmap summarizing fold change of differential expression of cytokines and growth factors in supernatants of fibrosis models (TGF-β-treated versus untreated) and iFA model (day 13 versus day 4) (n = 3 in duplicate). Heatmaps show log-base-2-transformed data for each experiment mean expression (n = 3 in duplicate) of genes with p value < 0.05 in at least one of the samples per protein.

(D) HMGB1 levels determined from conditioned media in the fibrosis models (with and without TGF-β treatment) and the iFA model at day 13 relative to day 4 (n = 6).

Data represent the mean ± SEM; ****p < 0.0001 ***p < 0.001, and **p < 0.01 using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

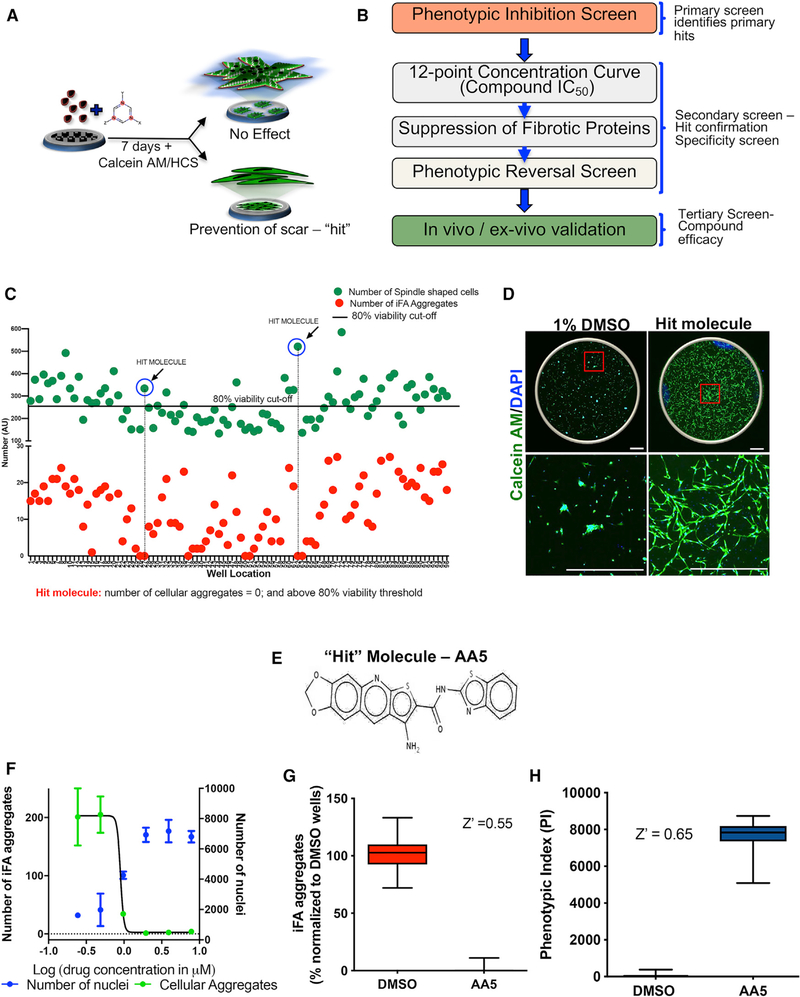

High-Content Phenotypic Screening Identifies an Anti-Fibrotic Small Molecule

Next, given the progressive fibrotic phenotype seen in the iFA model, we developed a phenotypic screening assay to identify potential anti-fibrotic drugs. Phenotypic assays are ideal when screening for compounds that reverse disease-related cellular phenotypes without knowing the precise biological causalities. Moreover, such approaches are more likely to yield therapeutically tractable hits than standard enzyme-based assays with better prognosis in translation to the clinic. In our case, our primary screen was an iFA-prevention assay without a priori knowledge of any targets (Figures 4A and 4B). We identified various cellular phenotype parameters that appeared relevant, such as size, fluorescence intensity of the iFA phenotype, the shape factor of the cells/aggregates, and the cells’ viability in the presence of viability dyes (Calcein AM) (Figure S4A).

Figure 4. High-Content Phenotypic Screening Identifies an Anti-fibrotic Small Molecule.

(A) Cartoon representing the phenotypic drug screening iFA-prevention assay.

(B) Schematic depicting the screen workflow.

(C) Superimposed representative scatterplot from a single 96-well plate of the iFA-prevention assay. Green and red dots represent the total number of live cellsand iFA phenotypes, respectively, in each well analyzed per the parameters listed in Figure S4A. DMSO controls were in wells A1-H1 and A12-H12. The black line is the statistical cutoff of the DMSO control used for selecting primary hits (≥80% viability). A hit molecule would be identified as one that has no iFA phenotype (red dot is near/at 0) and cell viability greater than 80% (green dot is above the cutoff line).

(D) Prevention of the iFA phenotype in the well containing our “hit” molecule, AA5, compared to DMSO control. Scale bar, 750 μm.

(E) Chemical structure of AA5.

(F) Dose response of AA5 showing IC50 of 0.9 μM.

(G) A pre-presentation of the assay performance with Z′ calculation demonstrating a robust assay performance using the number of iFA phenotypes.

(H) The assay performance with Z′ calculation demonstrating again a robust assay performance using the phenotypic cell index (PI).

The most desired hit compounds would prevent the cells from forming the iFA phenotype and instead allow them to grow as a monolayer of viable cells with a spindle-shaped cell morphology due to decreased fibroblast activation similar to the morphology of parent primary fibroblasts cultured on hydrogels (Figures 1A and S1L). For our initial primary screen, we used a simple data-mining strategy that would differentiate the iFA phenotype and spindle-shaped cells using area, fluorescence intensity, and morphometric shape analysis (Figure S4A).

We exposed our iFA model to compounds from in-house-curated libraries of ~17,000 small molecules at a concentration of 10 μM for 7 days. Wells with only DMSO were used as negative controls to assess drug efficacy for preventing the progression of the iFA phenotype. To determine assay robustness, we analyzed the iFA phenotype over multiple plates and experimental runs. The total fluorescent signal generated per single iFA phenotype was found to be proportional to its size. We defined wells that had more than 80% viable cells compared to the DMSO-treated controls as not impacted by the toxicity of the compounds. Using the standard plate layout in the NIH assay guide, we monitored the signal to detect deleterious effects such as drifts or edge effects. All per-well measurements were normalized to DMSO control averages. From the primary screen, we identified a compound, AA5, that completely prevented the progression of the iFA phenotype (AA5 prevention) (Figures 4C–4E). Instead, the cells resembled mesenchymal-like cells and covered the well as a monolayer at concentrations ranging from 2 to 150 μM with an IC50 of ~0.9 μM (Figures 4F and S4B). There are currently no compounds that have been identified to prevent progression of fibrosis. We further refined our primary screen by using a full plate of DMSO as solvent control and AA5 as tool compound to assess standard parameters (Z′, SD, and coefficient of variance [CV]) for assay performance. We benchmarked our assay by data mining for the presence or absence of iFA phenotype and single spindle-shaped cells. We were able to achieve a Z′ = 0.55 for the presence/absence of iFA phenotype. We were able to further improve our assay performance by deriving a phenotypic index (PI) that is calculated as follows: PI = (area covered in the well) × (number of nuclei)/log (number of iFA phenotypes detected + 5). Using the PI, we obtained a Z′ = 0.65, which is an excellent assay (Figures 4G and 4H). The numerical value of 5 that is added to the iFA phenotype is roughly 1 SD of the number of iFA phenotypes found in an average well.

For the iFA phenotype analysis, the signal to basal ratio (S/B) ratio was 59.3-fold, and the CVs were 0.31 for the DMSO-treated wells and 3.5 for the AA5-treated wells (Figure 4G). For the PI analysis, the S/B ratio was 76-fold, and the CVs were 0.63 for the DMSO-treated wells and 0.11 for the AA5-treated wells (Figure 4H). Thus, our assay is suitable for high-throughput screening.

Our hit rate from the primary screen (chemical and functional genomic screens) was 0.1%, which included hits that could partially or completely inhibit the iFA phenotype. For example, the JAK/STAT pathway is known to be important in driving fibrosis in many organs (Mair et al., 2011; Milara et al., 2018; Mir et al., 2012). Our chemical screen identified the JAK2 inhibitor CEP-3379, and our functional genomic screen identified knockdown of STAT5b as hits in our primary screen (Figure S4C). The gene expression of ACTA2/COL1A1 was consistent with the phenotype observed (Figures S4D and S4E).

Characterizing the Anti-fibrotic Activity of AA5

As AA5 is an unknown small molecule, we decided to characterize its anti-fibrotic effect further. We first determined if AA5 had an effect on cellular proliferation. DMSO- and AA5-treated cells were labeled for 6 h with EdU at different time points during the iFA phenotype progression, and we did not detect any significant difference in proliferation rates at 10 μM concentration (Figures S4F and S4G). Next, we examined the anti-fibrotic effect of AA5 by profiling the expression of several genes involved in tissue remodeling during repair. Downregulation of the gene expression of the fibrotic markers α-SMA, collagen I, TIMP-3, and POSTN in response to treatment with AA5 was further confirmed by immunoblotting, Luminex, and immunofluorescence analysis (Figures S4H and S4I).

As a secondary screen, we determined whether treatment with AA5 was sufficient to promote the resolution of a fibrotic phenotype. 13 days after the generation of the iFA phenotype, cells were treated with 10 μM AA5, and within 48 h, AA5 resolved the iFA phenotype based on the reduction in levels of collagen I and α-SMA (Figures 5A and S5A–S5C; Videos S2 and S3). We also examined the outcome of AA5 prevention and AA5 resolution on cell stiffness and found that AA5 treatment significantly decreased cell stiffness (Figure 5B). Additionally, we found that secreted levels of HMGB1 and percentages of SSEA4+ cells were attenuated with AA5 treatment (Figures 5C, S5D, and S5E).

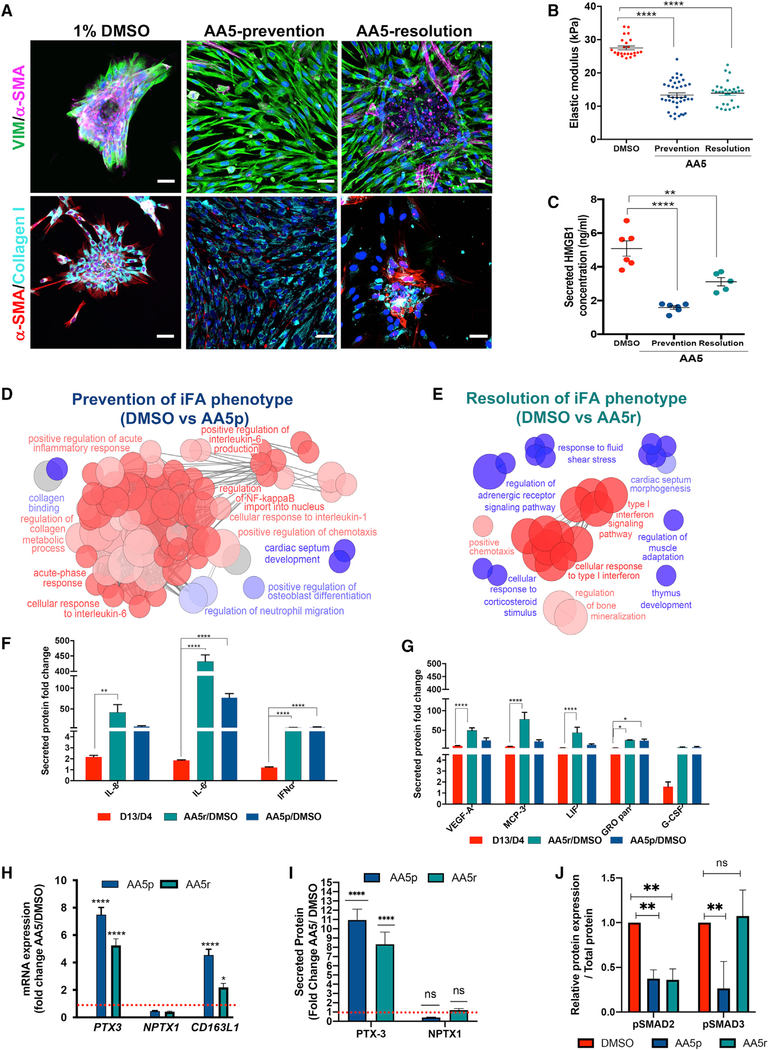

Figure 5. AA5 Induces Acute-Phase Response Proteins Promoting Resolution of Fibrosis.

(A) Representative DMSO-treated, AA5-prevention (AA5p), and AA5-resolution (AA5r) iFA cultures immunostained for VIM and α-SMA (top panels) and collagen I and α-SMA (bottom panels). Scale bar, 50 μm.

(B) Quantification of stiffness of the cells in the DMSO-treated, AA5p, and AA5r iFA model.

(C) Secreted levels of HMGB1 in the iFA model during AA5p and AA5r treatments in comparison to DMSO-treated controls.

(D and E) ClueGO clustering analysis results of up- (red) and downregulated (blue) genes in a pairwise comparison of AA5p (D) or AA5r (E) treatment with DMSO-treated iFA model. p values of ≤ 0.05 are shown.

(F) Cytokine profiles of acute-phase proteins in supernatants of the iFA model at day 13 relative to day 4 cytokines in AA5r or AA5p versus DMSO-treated cells(n = 4 in duplicate).

(G) Cytokine profiles of proteins secondary to acute-phase response in supernatants from the iFA model at day 13 relative to day 4 cytokines in AA5r or AA5pversus DMSO-treated cells (n = 4 in duplicate).

(H) Comparison of gene expression fold change levels of PTX3 and NPTX1 and scavenger receptor CD163L1 in the AA5r- and AA5p-treated iFA model when compared to the DMSO-treated iFA cultures (n = 5).

(I) Time-dependent fold increase in secreted PTX3 and NPTX1 on AA5p and AA5r treatment measured in supernatants collected on day 13 (AA5p) and 48 h (AA5r) of treatment when compared to DMSO controls in the iFA model (n = 4).

(J) Densitometric analysis depicting fold change of p-SMAD2/3 in the iFA model with DMSO, AA5-prevention, and AA5-resolution treatments analyzed by immunoblotting normalized to total protein.

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, and **p < 0.01 using one- or two-way ANOVA and Dunnett or Sidaks’s multiple comparison test.

To determine if AA5 exhibits its preventive and resolutive effects on the iFA phenotype by modulating similar cellular mechanisms, we performed transcriptomic analysis of the iFA model post-AA5-prevention and AA5-resolution treatments. Using rank-rank hypergeometric overlap (RRHO) analysis (Plaisier et al., 2010), we observed a strong hypergeometric overlap between the differentially expressed genes upon AA5-prevention and AA5-resolution treatments, suggesting overlapping mechanisms by which AA5 prevents and resolves the iFA phenotype (Figure S5F). To determine how significantly AA5-treated cells correlated to healthy and fibrotic lung, we performed RRHO analysis between the differentially expressed genes in healthy and IPF lung datasets compared to datasets of differentially expressed AA5-prevention- (Figure S5G) and AA5-resolution-treated (Figure S5H) genes. We observed medium to strong hypergeometric overlap between treated (AA5 prevention or AA5 resolution) and untreated (fibrotic surrogate) iFA cultures as compared to the whole lung healthy and IPF tissues, suggesting AA5 treatment drives cells toward a healthier lung phenotype. These findings further support the iFA model as a tractable model to study progressive fibrosis.

Next, to understand the biological activity modulated by AA5, we performed differential gene expression analysis using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments in the iFA model treated with AA5 in both preventative (AA5 prevention) and resolutive (AA5 resolution) experiments. We performed functional cluster analysis using the ClueGo tool and observed upregulation of Gene Ontology pathways such as response to acute-phase reactants, positive regulation of the acute inflammatory response, and regulation of NF-κB import to the nucleus. Notably, positive regulation of chemotaxis and activation of acute-phase proteins such as IL-6, type I interferon (IFN), and IL-1 were observed after both AA5-resolution and AA5-prevention treatments (Figures 5D, 5E, S5I, and S5J).

Because of the inflammatory signature induced by AA5 prevention and AA5 resolution, we further examined the acute-phase response in the iFA model treated with and without AA5. We observed increased secreted levels of the acute-phase response cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-α with both AA5-prevention and AA5-resolution treatments using Luminex assays (Figure 5F). Acute-phase response cytokines play a central role in regulating the innate immune response to infection, tissue injury, and DAMPs. Additionally, we observed an increase in the acute-phase signaling secondary cytokines MCP-3, VEGF, CSF3, and GRO (Figure 5G). Taken together, AA5 induced an acute-phase response and inhibition of HMGB1-mediated chronic cytokine signaling that is associated with scar resolution.

As a consequence of the acute-phase response, pentraxins (PTXs) are released (Bottazzi et al., 2010), and scavenging receptors such as CD163L1 on phagocytic cells are activated. Scavenger receptors such as CD163L1 play important roles in regulating tissue repair (Doni et al., 2015). Our data showed upregulation of modulators of tissue repair, PTX3 and CD163L1, within 24 h of treatment with AA5 resolution (Figure 5H). The acute-phase signaling seen in the iFA model treated with AA5 prevention and AA5 resolution was consistently associated with progressively increasing amounts of PTX3 protein (Figure 5I), which also correlated with the iFA prevention and resolution phenotypes (Figures 4 and 5). Additionally, we saw attenuation of TGF-β signaling with downregulation of pSMAD2/3 activity with AA5-prevention and AA5-resolution treatments (Figures 5J and S5K). p-SMAD2 and p-SMAD3 were differentially regulated in the prevention and resolution treatments with AA5, and differential regulation of p-SMAD2 and p-SMAD3 has also been reported during a regenerative process (Denis et al., 2016). Taken together, AA5 appears to induce an acute-phase response that is associated with scar resolution.

Ex Vivo Anti-fibrotic Efficacy of AA5 in Human LSCs from Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

As a tertiary screen, we evaluated the efficacy of the hit molecule AA5 using an ex vivo model of lung fibrosis (Morin et al., 2013) (Figure 6) and two in vivo models of IPF and ocular mucosal fibrosis (Ahadome et al., 2016a, 2016b) (Figure 7). For nearly three decades, more than 90% of drug candidates identified to be effective in animal models of fibrosis have failed in clinical trials (Raghu, 2017; Spagnolo and Maher, 2017). Therefore, to further strengthen our tertiary screen, we examined the efficacy of AA5 in a human ex vivo model using fibrotic lung samples. A lung slice culture (LSC) system was established from end-stage IPF patient lung tissue obtained at the time of lung transplantation. Thin fibrotic lung slices were incubated with AA5 (10 μM) or DMSO (1%). The LSCs were viable at 48 h, as determined by immunostaining with the proliferation marker PCNA (Figure S6A). Following culture, RNA was isolated and quantitative real-time PCR was used to determine expression of fibrosis markers. AA5 treatment significantly reduced ACTA-2, COL1A2, and TGF-β3 (but not TGF-β1/2) mRNA expression within 48 h relative to DMSO-treated LSCs (Figure 6A). Further, we saw decreased levels of secreted TGF-β3 (but not TGF-β1/2), TIMP-4, and POSTN protein expression and increased secretion of matrix degrading proteases such as MMP-9 and urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) with AA5 treatment, consistent with a tissue repair response (Figures 6B, S6B, and S6C). Additionally, immunostaining for HMGB1 revealed exclusively nuclear staining in the AA5-treated LSCs compared to the DMSO-treated LSC controls. This was further confirmed by the Luminex assay that detected markedly decreased secreted HMGB1 with AA5 treatment (Figures 6C and 6D). Additionally, the fibrosis-initiating SSEA4+ cells (Xia et al., 2014) were significantly reduced (>50%; p value < 0.001) upon AA5 treatment (Figure 6E).

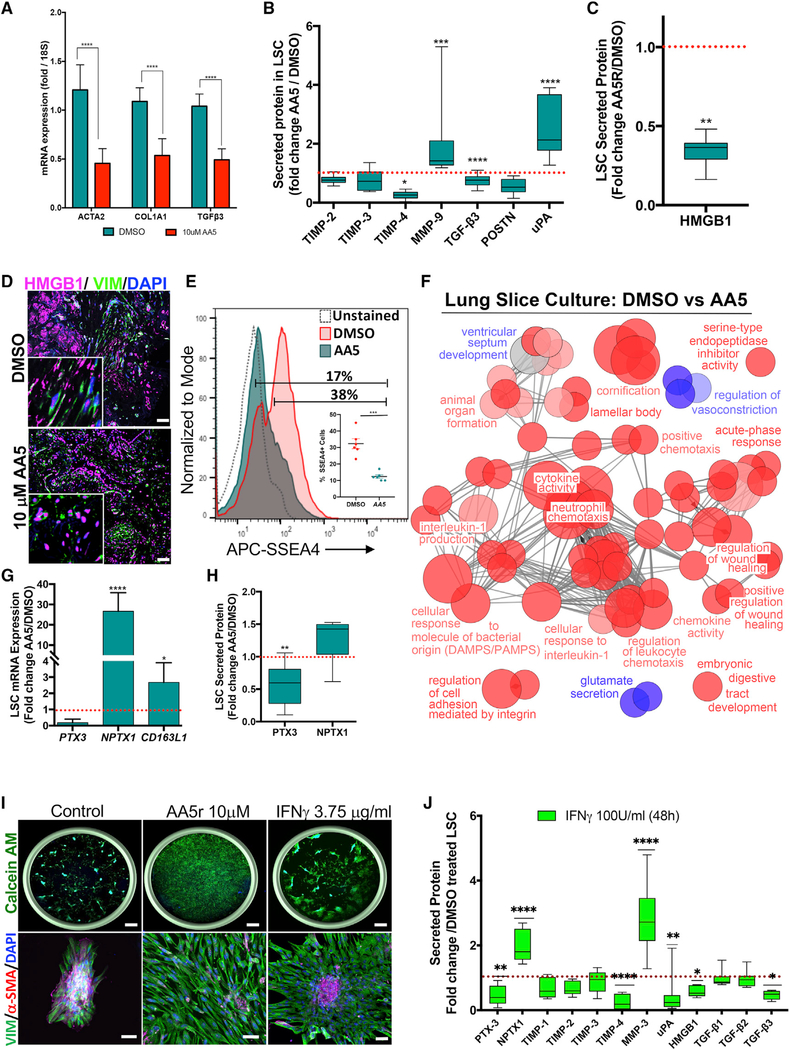

Figure 6. Ex Vivo Analyses Confirm the Anti-fibrotic Efficacy of the Hit Molecule in Human Fibrotic Samples.

(A) Fold change of gene expression in AA5-treated lung slice cultures (LSCs) relative to DMSO-treated controls at 48 h (n = 4). Data represent mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

(B) Relative secreted levels of fibrosis-related proteins in supernatants of AA5-treated LSC cultures compared to DMSO-treated controls at 48 h (n = 9).

(C) Relative secreted levels of HMGB1 in AA5-treated LSC cultures compared to DMSO-treated controls at 48 h (n = 9).

(D) Representative image of DMSO- and AA5-treated LSC stained for HMGB1 counter stained for VIM and DAPI. Insets are higher magnification images; scalebar, 50 μm.

(E) Representative FACS plots revealing expression of SSEA4+ population in LSCs treated with DMSO or AA5. Inset shows quantitative data of SSEA4+ cells. Data represent mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 using two-tailed paired t test.

(F) ClueGO clustering analysis results of up- (red) and downregulated (blue) genes in a pairwise comparison of AA5- versus DMSO-treated LSCs (p % 0.05).

(G and H) Fold change of expression of PTX3, NPTX1 and CD163L1 in AA5-treated LSCs relative to DMSO-treated controls at 48 h at mRNA (G; n = 6) and secreted protein (H; n = 6) levels.

(I) Representative images from wells of the iFA model treated with the DMSO, 10 μM AA5, or 3.75 μg/ml IFN-γ stained with Calcein AM and DAPI (left panel). Scale bars, top panel - 750 μm, bottom panel - 50 μm.

(J) Relative fold change of secreted proteins in LSCs treated with 3.75 μg/ml rIFN-γ for 48 h in comparison to DMSO-treated controls (n = 4).

Data represent min-max and median protein abundance; ****p < 0.0001 ***p < 0.001 **p < 0.01 *p < 0.05 using two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

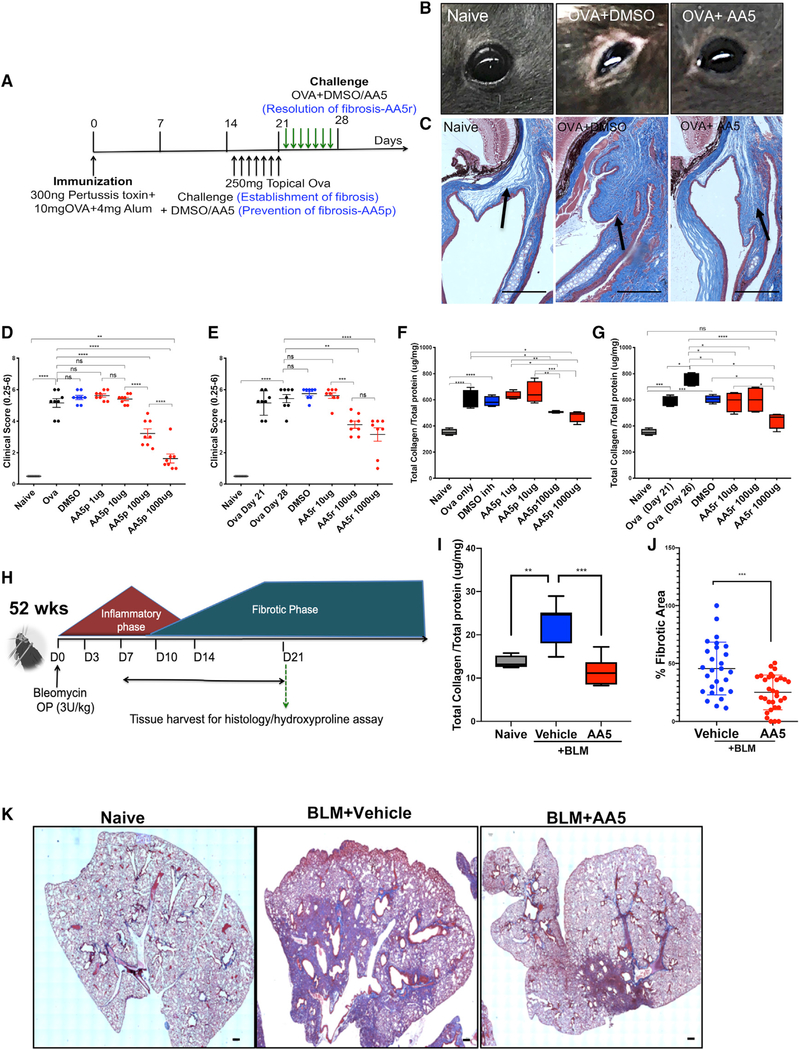

Figure 7. In Vivo Analyses Confirm the Anti-fibrotic Efficacy of the Hit Molecule.

(A) Schema illustrating the experiment to induce and treat ocular fibrosis in mice in a dose-dependent manner.

(B) Representative images of eyes of mice from naive, OVA-sensitized and either DMSO- or AA5-treated animals on day 21.

(C) Representative Gömöri trichrome stained sections of whole eyes (n = 12 per group). Scale bar: 50 μm.

(D and E) Ocular surface inflammatory score in OVA-treated mice (n = 12) treated daily with topical eye drops containing DMSO or (0.1–1,000 μg) AA5 in fibrosis prevention (D) and resolution (E) studies.

(F and G) Total collagen content in conjunctival tissue in naive, OVA-, DMSO-, and AA5-prevention (F) or AA5-resolution (G) treated animals following ocular scarring (n = 12).

(H) Schema illustrating the experiment to induce and treat IPF in mice.

(I) Hydroxyproline content in lung tissue collected on day 21 post -BLM injury with and without AA5 (n = 8).

(J) Percentage fibrotic area measured using the spline contour tool in each sectioned lobe. Data represent mean of two samples analyzed by unpaired t test(***p < 0.001). Related to Figure S7A.

(K) Representative trichrome-stained sections of BLM-treated lungs with and without AA5 collected at day 21 used for scoring fibrotic area in Figure 7J. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Data represent min-max and median. ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05 using one-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

AA5 Induces Acute-Phase Response Proteins Promoting Resolution of Fibrosis

To understand the cellular responses modulated by AA5, we performed RNA sequencing on LSCs from six different IPF patients treated with AA5 or DMSO. Pathway enrichment analysis using ClueGo showed a significant enrichment of acute-phase signaling with nodes including neutrophil chemotaxis, IL-1 signaling, and cellular response to DAMPs (Figures 6F and S6D). Therefore, as with the iFA model, activation of acute-phase response genes and fibrosis-resolution genes with AA5 treatment were consistently observed in the LSCs.

Interestingly, unlike AA5 treatment in the iFA model, we did not observe increasing levels of secreted protein PTX3 in LSC. Instead, we observed the paralog of PTX3, neuronal pentraxin 1 (NPTX1), to be upregulated in the LSCs at the mRNA and protein levels (Figures 6G, 6H, and S6E). Scavenger receptors are shed and secreted following phagocytic cell activation (Canton et al., 2013). Similar to the AA5-treated iFA cultures, we observed the scavenger receptor CD163L1 to be upregulated and secreted in the AA5-treated LSCs (Figures 6G and S6E).

These data suggest that AA5 exhibits its anti-fibrotic activity by activating an acute-phase response and playing an immune regulatory role. IFNs have immune-regulatory effects and are known anti-fibrotic cytokines. To further confirm the activity of AA5, we treated the iFA model with recombinant IFN-γ. Cells treated with recombinant IFN-γ showed more spreading of cells and less prominent iFA phenotype than the DMSO control, suggesting a partial rescue of the iFA phenotype (Figure 6I). Consistent with this, treatment of the LSCs with recombinant IFN-γ also revealed a similar expression profile of fibrosis-related resolution proteins when treated with AA5 (Figure 6J). This was accompanied by regulation of complex fibro-suppressive inflammatory processes such as activation of MMPs and uPA and downregulation of TIMPs, elastin, fibronectin, collagens, LOX, and secreted DAMPs. Our data suggest that AA5 exhibits its anti-fibrotic effect by activating an acute-phase response with cytokines such as IL-6 and IFNs.

AA5 Ameliorates Fibrosis in a Murine Model of Ocular Mucosal Fibrosis

For the in vivo studies, we evaluated the effect of AA5 in both prevention and resolution of fibrosis. Mice were sensitized with ovalbumin (OVA) for 14 days and then challenged with topical eye drops of OVA for an additional 7 days for the establishment of progressive ocular mucosal fibrosis (Figure 7A). During this period, OVA-challenged mice exhibited severe eyelid edema, chemosis, conjunctival redness, and tearing compared to naive mice, consistent with an inflammation driven fibrotic response (Ahadome et al., 2016b). DMSO (1%) or AA5 (0.001–1 mg/1% DMSO) was either applied to the ocular surface on day 14 together with the OVA challenge for the prevention of fibrosis studies or applied on day 21 for 7 days following the establishment of fibrosis to determine the efficacy of AA5 in resolving fibrosis in a dose-escalation study. The eyes that received 0.1 and 1 mg AA5 showed less clinical swelling, tearing, and inflammation than DMSO-treated eyes in both the preventive and resolutive treatments, and this correlated with the conjunctival histology (Figures 7B–7E). The mice were sacrificed at the end of the treatment period, the eyes were collected, and the conjunctivae were dissected out for total collagen estimation. Total collagen content in the conjunctivae was quantified using a hydroxyproline assay. We observed a significant reduction in the collagen content of the conjunctivae after AA5-prevention and AA5-resolution administration at 0.1- and 1-mg doses that correlated with the eye histology (Figures 7C, 7F, and 7G), suggesting that AA5 was able to ameliorate OVA-induced fibrosis in a dose-dependent manner.

AA5 Suppresses BLM-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in Aged Mice

To define the anti-fibrotic effect of AA5 in a second in vivo model of fibrosis, we used the bleomycin (BLM) model of lung injury in aged mice (Figure 7H). 52-week-old mice were challenged with BLM (3 U/kg) by the oropharyngeal route to induce lung injury, followed by systemic administration of AA5 (20 mg/kg) or DMSO from days 7 to 21 post-BLM injury. Naive mice were maintained as controls. The mice were sacrificed on day 21, and the total collagen content of the lungs was quantified using the hydroxyproline assay. BLM-challenged mice had elevated amounts of total collagen compared to their naive controls. In contrast, mice treated with AA5 demonstrated significantly reduced total collagen compared to the vehicle-treated controls (Figure 7I). The percentage of fibrotic areas from each section was quantified using Masson trichrome stain, tiled and imaged on a Zeiss Axioscope microscope at 2.5×, and quantified using the spline contour tool using ZEN 2011 software. This demonstrated that the vehicle-treated mice displayed significantly more fibrotic areas than AA5-treated animals following challenge with BLM (Figures 7J, 7K, and S7A).

DISCUSSION

Four major phases of the fibrogenic response have been described that include initiation of the injury, activation of effector cells followed by production of ECM, and then failure to resorb the ECM with continued deposition of ECM (Rockey et al., 2015). Our iFA model mimics all four fibrotic phases with the secretion of the DAMP molecule HMGB1, the activation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, the activation of TGF-β, the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and the progressive deposition of collagen, thereby creating a phenotypic surrogate for progressive fibrosis.

Fibrotic diseases resulting in organ remodeling and failure are responsible for ~45% of all deaths worldwide. Currently, there are very few effective therapies and none that can halt or reverse progressive fibrosis (Rockey et al., 2015). Most in vitro models for fibrosis utilize the exogenous addition of pro-fibrotic modulators such as TGF-β to their cultures to drive a fibrotic response for 48 or 72 h, after which gene and protein expression for markers of myofibroblast activation and ECM production are investigated. This approach uses a time course that is likely too short to model disease progression and is also subject to modulator-driven bias. In contrast, our model does not utilize the addition of any external fibrotic modulators and is hence unbiased and target-agnostic for progressive fibrosis disease modeling and drug discovery. Further, other current in vitro models only seek to inhibit fibrosis; that is, unlike our model, these models cannot be used to assess a reversal of fibrosis. Importantly, the lack of relevant mouse models for the progressive nature of fibrosis is also widely acknowledged (Degryse and Lawson, 2011).

We surmise that iPSCs are uniquely able to generate this phenotype, because they are capable of differentiating to multiple different progenitor cell types, and each cell type displays plasticity and can give rise to the other cell types. The pathological effects of progressive fibrosis are associated with cell plasticity, which plays a major role in the phenotypic transitions in cell populations that contribute to tissue remodeling in organ fibrosis (Nieto, 2013; Varga and Greten, 2017). Cellular plasticity is a key feature of fibrosis involving bidirectional interactions between epithelial cells and fibroblasts and a dynamic interplay between ECM deposition and regression (Rockey et al., 2015). The hierarchical relationships among stem cells, lineage-committed progenitors, and differentiated cells remain unclear in several tissues due to a high degree of cell plasticity, allowing cells to switch between different cell states in both regeneration and pathological conditions. While strict lineage hierarchies exist during development and homeostatic tissue turnover, this is not the case in pathological conditions such as fibrosis. These phenotypic transitions are commonly seen as dedifferentiation (Tetteh et al., 2015) or transdifferentiation (Tata and Rajagopal, 2016) and epithelial-to-mesenchymal and mesenchymalto-epithelial transitions (Fabregat and Caballero-Díaz, 2018; Stone et al., 2016). Cell plasticity is also apparent from single-cell RNA-sequencing studies from fibrotic lung where individual epithelial cells express markers of both distal lung and conducting airways, demonstrating that undetermined cell types are a characteristic feature of fibrotic tissue (Xu et al., 2016). In addition, during acute kidney injury, metabolic constraints have been shown to alter the epithelial features of renal proximal tubular cells to undergo a phenotypic switch and promote fibrogenesis, leading to chronic kidney disease (Rastaldi et al., 2002; Xu-Dubois et al., 2013). Circulating bone-marrow-derived cells can also acquire both and antifibrotic phenotypes in liver and kidney and potential other fibrotic organs (Campanholle et al., 2013; Trautwein et al., 2015). Single cell RNA-seq analysis is a very powerful tool to define cell types using unsupervised clustering based on the whole transcriptome (Pal et al., 2017) and may be a useful tool to identify common cellular plasticity signatures at the single-cell level across fibrotic organs and our model.

Inflammation has been shown to drive fibrosis. Our studies suggest that altering the inflammatory milieu can switch the fibrotic process to a resolutive one, and this is an important area for further studies. Inflammatory phagocytic cells are involved in inflammation at all stages of the fibrotic process in various organs such as lung, kidney, and liver. Following injury, they promote fibrosis by activating NF-κB and secreting profibrotic mediators such as TGF-β, which induces fibroblast/myofibroblast activation and ECM deposition. However, they also behave as pro-resolutive cells and facilitate resolution of fibrosis by producing MMPs and proteolytic enzymes such as uPA and cathepsins that degrade fibrotic ECM (Adhyatmika et al., 2015; Karlmark et al., 2010; Reddy et al., 2014; Tighe et al., 2011). The pro-resolutive phagocytic cells, such as macrophages, function to restore balance in the affected tissue. For example, they function by reducing DAMP signaling, increasing apoptotic cell clearance, restoring TIMP/MMP balance, and reducing ECM content (Adhyatmika et al., 2015; Galli et al., 2011) in line with the tissue repair process. Consistently, in animal models of lung and liver fibrosis, depletion of macrophages during the inflammatory phase of fibrosis resulted in a reduction in ECM deposition. In contrast, macrophage depletion at the repair phase revealed aggravated ECM deposition (Boorsma et al., 2013; Duffield et al., 2005; Gibbons et al., 2011; Song et al., 2000). Furthermore, inhibition of NF-κB signaling in the intestine and skin has been shown to result in immune homeostasis dysregulation and poor survival outcomes (Wullaert et al., 2011). Similarly, TNF-α, which is predominantly secreted by macrophages, has been shown to promote fibrosis. It is also produced by macrophages during the resolutive phase, and mice that are deficient in TNF-α demonstrate delayed resolution of BLM-induced lung fibrosis (Redente et al., 2014).

Our data suggest that approaching inflammation-driven fibrosis by targeting endogenous agonists of resolution may offer an attractive strategy to treat progressive fibrosis. Targeting endogenous agonists of tissue repair for the treatment of IPF is currently being tested in a clinical trial with inhaled delivery of IFN-γ for a localized effect, since parenteral delivery of IFN-γ did not show any benefit (King et al., 2009).

STAR⋆METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by lead contact, Brigitte Gomperts (bgomperts@mednet.ucla.edu). This study did not generate new unique reagents.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

University of California iPSC lines were generated from IPF lung tissue obtained at the time of lung transplantation and from skin biopsies from IPF patients. Both male and female samples were used. Additionally, the following iPSC lines from Boston University were used: BU1, BU2, BU3, T1 1Cr NKX2.1, T3 2Cr NKX2.1 and T4 32Cr NKX2.1. The details are listed in Table S1.

Primary Fibroblasts

Primary fibroblasts were freshly isolated from healthy and IPF lung tissue and skin and heart biopsies. Both male and female lines were used. Since the cells were largely compared to our iFA model with limited set of samples, no conclusion could be drawn on sex as a biological variable.

Human subjects

Deidentified human donor and IPF explanted lung tissue prior to lung transplantation were used for reprogramming and ex vivo lung slice culture studies. Patients for the generation of IPSCs were randomly chosen and were both male and female. We did not find any biological variable with respect to sex in the generation of our model. With respect to the ex vivo lung slice culture experiments, as these were efficacy experiments on a limited set of samples, no conclusions can be drawn on sex as a biological variable. The University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board determined that this study was exempt from review since the samples were all deidentified and considered waste tissue.

Mice studies

Wild-type C57BL/6 mice aged either 8–10 weeks (ocular mucosal fibrosis studies) or 52 weeks (lung fibrosis studies) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Animals were housed together in groups and maintained in a pathogen-free animal facility in a 12-h light-dark cycle in a temperature-controlled room (21.1 ± 1.1°C), with ad libitum access to water and food at the Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine at UCLA. All procedures were carried out under the UCLA Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

METHOD DETAILS

Generation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

For the generation of iPSCs, skin and lung biopsies and PBMCs were procured with appropriate patient consent and institute IRB approval. The iPSCs were generated according to established protocols (Karumbayaram et al., 2012). Briefly, the punch biopsy samples were chopped and incubated in 2% animal origin free collagenase solution for 90 min at 37°C. The dissociated cells were plated in MSCGM-CD (Lonza) medium to generate primary fibroblasts. For the generation of iPSC’s, 1 × 105 primary fibroblasts were transduced with STEMCAA (kind gift from Dr. Darrell Kotton, Boston University, MA) vector concentrate (7 × 106 TU/ml) in MSCGM-CD medium. Five days post-infection, cells were re-plated in 50:50 TeSR2/Nutristem containing 10 ng/ml bFGF until iPSC-like colonies appeared. The colonies were picked mechanically and cultured in CELLstart-coated dishes. Three independent iPSC lines per tissue sample were generated.

Differentiation of iPSC into mesenchymal-like cells to model progressive fibrosis

Differentiation of iPSC for modeling progressive fibrosis was generated according to published protocols (Wilkinson et al., 2017). Briefly, iPSCs were dissociated using 1 mg/ml of dispase, rinsed twice and then cultured in non-adherent dishes in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1x Glutamax, 10nM Non-essential amino acids and 0.1mM monothioglycerol (MTG) for the generation of embryoid bodies. After 4 days, the embryoid bodies were collected gently and plated on gelatinized dishes to allow to adhere and cultured in media containing DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1x Glutamax and 10nM non-essential amino acids and allowed to differentiate for an additional two weeks. The outgrowths from the embryoid bodies were collected by trypsinization and passaged for expansion and cryopreservation.

Generation of an Induced Fibroblast Activation (iFA) Phenotypic Surrogate of Progressive Fibrosis

Mesenchymal-like cells were cultured on 13 kPa functionalized polyacrylamide gels that were prepared as follows. 187.5 μL of 40% acrylamide, 60 μL of 2% bis-acrylamide and 8.55 μL of sodium bisulfate in a final volume of 990 μL of water was incubated for 20 min at room temperature to degas the mixture. To this mixture, 0.10% ammonium persulfate and 0.15% TEMED were added, mixed and 100 μL of the solution was added onto a 0.4% 3-(Trimethoxysily) propyl methacrylate pH 3.5 treated coverslip. A 2% dimethyldichlorosilane in chloroform treated round glass coverslip was then inverted on the acrylamide solution and allowed to polymerize for 15 min between the two surfaces. The top coverslip was gently removed, and the bottom coverslips with the hydrogel were transferred to appropriate multi-well low adherent tissue culture plate containing coupling buffer (0.1 M sodium phosphate dibasic, 0.1 M sodium phosphate monobasic) pH8. To functionalize the hydrogel, 1 part of 0.1 M p-benzoquinone in dioxane was added to the hydrogels containing 4 parts of coupling buffer and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The gel was then successively washed with 20% dioxane in water, water, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer at pH 4.0 containing 1.0 M sodium chloride, 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate solution at pH 8.5 containing 1.0 M sodium chloride, and finally with coupling buffer at pH 7.5. The hydrogels were then coated with 0.1% gelatin for 2 hr prior to seeding the cells. Cells were seeded at a density of 3000 cells/cm2.

Activated PAI-1 Activity

Quantitation of biologically active TGF-β levels was performed using mink lung epithelial cells stably transfected with plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promoter/luciferase construct, in which luciferase activity represents bioactive TGF-β levels according to established protocols (Mazzieri et al., 2000). Briefly, cells in the iFA model were serum starved for 30 hr and conditioned media was collected at different time points. 2.5×104 mink lung epithelial cells were seeded per well in a 96-well plate and allowed to adhere to the plate for 3 hr. The medium was then replaced with conditioned media from the iFA model. Separately, control medium containing increasing concentrations (10ng/ml – 30 pg/ml range) of rTGF-β1 was used to generate a standard curve. After 24 hr of incubation at 37°C, cells were lysed with equal quantity of Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and luminescence was measured using a DTX 880 multimode detector. The luciferase activity that was recorded as relative light units (RLU) was interpolated to TGF-β1 activity (pg/mL) using the TGF-β standard curve.

Assessing Proliferation by EdU Labeling

Cells were incubated with 10μM EdU (Invitrogen) at specified time points of culture for 6 hr, fixed with 4% PFA, and detected by staining with Alexa594-azide according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were additionally counterstained with Vimentin and/or α-SMA and DAPI.

Decellularization of Primary Fibroblasts and iFA Model

Coverslips were gently washed with PBS and subjected to repetitive 30-minute freeze-thaw cycles in water, six times in total. The water was then replaced with 25 mM ammonium hydroxide containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. The coverslip was then washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 10 minutes and processed for immunostaining.

Multiplex Analysis of Cytokines

The Milliplex human cytokine/chemokine Panel IV, human TIMP Panel 2, and human TGFβ 1,2,3 magnetic bead kits (EMD Millipore) were used per manufacturer’s instructions. Prior to plating, all samples tested for human TGFβ only were activated and neutralized with 1.0 N HCl and 1.0 N NaOH, respectively. Briefly, 25 μL of undiluted or treated cell culture supernatant samples were mixed with 25 μL of magnetic beads and allowed to incubate overnight at 4°C while shaking. After washing the plates with wash buffer in a Biotek EL×405 washer, 25 μL of biotinylated detection antibody was added and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature while shaking. 25 μL of streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate was then added to the reaction mixture and incubated for another 30 minutes at room temperature while shaking. Following additional washes, beads were resuspended in sheath fluid, and fluorescence was quantified using a Luminex 200 instrument. Similarly, a custom magnetic Luminex assay kit of select analytes (R&D Systems) was used per manufacturer’s instructions. Cell culture supernatants were prepared with a 2-fold dilution. 50 μL of diluted sample were added to 50 μL of provided micro-particle cocktail and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature while shaking. After washing with wash buffer, 50 μL of biotin antibody cocktail was added and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature while shaking. Following additional washes, 50 μL of diluted Streptavidin-PE was then added for incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature while shaking. The plate was then washed again and the micro-particles resuspended in 100 μL wash buffer. After an additional 2-minute incubation while shaking, the data was acquired using a Luminex 200 instrument. For all multiplex assays, data was analyzed using MILLIPLEX Analyst 5.1 software. Kits used were TGFβ 1,2,3 (MILLIPORE: TGFBMAG-64K-03), TIMP Panel 2 (MILLIPORE: HTMP2MAG-54K), Cytokine/Chemokine Panel IV (MILLIPORE: HCY4MG-64K-PX21); Custom Luminex (R&D: CUST01704 13). Multiplexing LASER Bead Technology service from Eve Technologies Corp (Calgary, Canada) was used to simultaneous analyze several cytokines, chemokines and growth factors in a single assay from the iFA model at specified time points using the Human Cytokine Array / Chemokine Array 64-Plex Discovery Assay based on a MILLIPLEX® MAP assay kit from Millipore according to their protocol. The assay sensitivities of these markers range from 0.1 – 55.8 pg/ml.

Quantification of Secreted HMGB1 and NPTX1

Conditioned media at different time points of progression of the phenotype, and on prevention and resolution drug treatments were collected and quantification of protein was performed using the IBL man HMGB1 ELISA kit or LSBio NPTX1 ELISA kits per manufacturer’s instructions. 10 μL of each supernatant sample was added to anti-HMGB1 polyclonal antibody-coated plate and incubated for 20 hours at 37°C. All liquid was then removed, and the plate manually washed 5 times with wash buffer. 100 μL of enzyme conjugate was then added and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing again, color solution was added at 100 μL per well and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Following an additional five washes, the plate was incubated with 90 μL of TMB substrate for another 15 minutes at 37°C in the dark. The reaction was then stopped by addition 100 μL of stop solution. Absorbance was measured at 450nm using a SpectraMAX Plate Reader. Data was analyzed using SoftMax Pro software.

In Situ Cell Elasticity Measurements Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

Tapping mode AFM using the Bruker BioScope Catalyst Atomic Force coupled with Zeiss LSM5 Confocal Fluorescence Microscope was used on the cells at 37°C in cell culture media. AFM deflection images of cells were used in the imaging experiment. In the force measurement, sharp silicon nitride AFM probes (tip radius, 20 nm) were employed (Bruker Corp., USA). The spring constants of AFM tips were calibrated to be 0.10–0.11 N m−1 and deflection sensitivities were 45–50 nm V−1, using Thermo K Calibration (Agilent Technologies, USA). The approaching/retracting speed of the AFM tip during the force curve measurement was 6 μm s−1. Force–distance curves were recorded to obtain cell elasticity (Young’s modulus, E) of individual cells. For each time point, at least 20 single cells, 20 cells at the base of the iFA and 20 cells at the tip of the scar were measured with over 15 force–distance curves per cell to obtain significant results. The Young’s modulus was calculated via the Scanning Probe Image Processor (SPIP) software (Image Metrology, Denmark) by converting the force–distance curves to force–separation curves and fitting the Sneddon variation of the Hertz model, which describes conical tips indenting elastic samples.

Fibrosis Models with the exogenous addition of TGF-β

Hepatic Stellate Cell (LX-2) was purchased from Millipore. Primary skin, healthy lung and IPF lung fibroblasts were prepared from punch biopsies collected from patient samples according to the Institution’s IRB approvals. Three patient lines were used for each experiment. 100,000 cells were seeded in a 35mm dish and allowed to grow to confluency of 48 hours. After a 24-hour serum starvation, the media was replaced with serum-free media containing either 2ng/ml rhTGF-β for the LX-2 cell line or 10ng/ml rhTGF-β for all other primary cultures. Untreated cultures in serum free were maintained as controls. After 48 hours with daily media changes, samples were collected for either RNA or protein analysis.

Phenotypic High-Content Drug Screen

A phenotypic high-content drug screen was established to identify compounds capable of preventing the iFA phenotype in a 96-well format. Toward this end we utilized an ImageXpress XL high-throughput imager with a 4x Plan objective (N/A 0.20) and image based focusing. Briefly, 100 μL media were plated in each well of 96 well plate using a Thermo Multidrop non-contact dispenser. Using a custom V&P pin tool mounted to a Beckman FX liquid handler, 1.5μL compounds or DMSO were added. Mesenchymal-like cells were added as a suspension using the Multidrop at a density of 3.5×103 cells/well. The resulting compound concentration was 10 μM. Cells were imaged after 7 days of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2: A final of 0.5 μg/ml of Calcein AM and/or 10 μg/ml propidium iodide (viability dye) with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 were added and imaged using the ImageXpress XL system. Data mining was performed using a custom module consisting of the following steps: The image background was removed using a top-hat filter with 25 μm round shape polisher. Next, we identified areas with iFA phenotype and individual spindle-shaped cells: iFA phenotypes were defined by size with a cut-off of 60 to 200 micron and an intensity of at least 200 gray scales over background. Individual spindle-shaped cells were identified as smaller objects with cut-offs from 15 to 100 micron and a lower intensity of at least 70 gray scales over background.

We also performed additional morphometric measurements by counting labeled cell nuclei and measuring total area covered with cells per well. The data resulting from the screen were batch exported through MetaXpress and uploaded into our Collaborative Drug Discovery (CDD) cloud based database (Ekins and Bunin, 2013). Hits were selected on a cut-off of more than 3 standard deviations from mean using data normalized to reference wells in each plate. IC50 values (the half maximal inhibitory concentration) from confirmation experiments were calculated from dose-response signal curves using the Prism software (GraphPad Software). Signal-to-background (S/B) ratio, standard variation and variation coefficients were calculated as the signal of DMSO treated wells divided by the signal of the hit compound (AA5) treated wells. We used Z’ values to measure assay quality which was calculated by the formula of Z’ = 1–3(SDTotal+SDBackground)/(MeanTotal–MeanBackground) (Inglese et al., 2006) where SDTotal and Mean-Total are the standard deviation and mean of signal for DMSO treated wells, and SDBackground and MeanBackground are the standard deviation and mean of signal for AA5 treated wells. Data normalization and curve fitting were performed as previously reported (Kariv et al., 1999). We obtained Z’ values for the number of iFA phenotypes and also calculated a phenotypic cell index as the product of cell number × area / Log(number of iFA phenotypes +5). The assay was standardized using 50% of the plate with 0% DMSO and 50% of the plate with 1% DMSO. This was done is triplicate per day and repeated on three different dates in order to determine DMSO toxicity and assay reproducibility with minimum-to-none inter-plate and intra-plate variability. Reproducibility was determined by averaging the number of foci in all the wells per plate and comparing to other plates run on the same day and different dates. Toxicity was determined as wells showing < 80% viability compared to the 0% DMSO wells. The assay was then run using the Prestwick chemical library and the LOPAC library (2560 compounds) in duplicate on two separate days in order to standardize the assay performance. Due to the lack of a tool compound, a positive control could not be used. For the primary screen, ~17,000 compounds were screened in singlets. Secondary screening using α-SMA and collagen deposition was employed to further ensure efficacy and resolution of the iFA phenotype of the compounds. For the resolution screen, cells were seeded in a 96-well plate as mentioned above and compounds were added at day 13 to analyze their capacity to resolve the iFA phenotype using the same readouts as above. Dose response experiments were carried out as in the secondary screen but with at least 12 steps of a 1:1 dilution resulting in final compound concentrations from 500 μM to high nanomolar ranges.

For the functional genomic screen, a pilot of 500 clones were custom-picked from our in-house arrayed shRNA libraries targeting about 100 genes with an emphasis in coverage of desirable target classes such as kinases, proteases, phosphatases, GPCRs and ion channels. Oligonucleotides encoding each shRNA were cloned into linear pLX304 and entry vectors by 5min room temperature ligations, transformation of TOP10 cells, and selection on LB/blasticidin broth according to the vector manuals (Transomics Technologies). To transfer RNAi cassettes to the desired destination vectors, one-hour LR Clonase reactions (Invitrogen) were performed, transformed into TOP10 cells, and selected with 10mg/ml Blasticidin. Clones were verified by restriction digest due to the high fidelity of the Gateway (Invitrogen) recombination reactions. Lentiviral particles were produced according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Functional titer was determined using the mesenchymal-like cell line to ensure optimal transduction using the formula (Number of colonies) × (Dilution factor)/0.01. Transductions were carried out in a final volume of 100 μL medium in 96-well plates seeded with 10,000cells/cm2 per well on day 2 of seeding. The following day, medium was replaced with complete medium supplemented with 10mg/ml Blasticidin. Resistant clones were grown out and cultured on 12kPa hydrogels in order to determine presence/absence of iFA phenotype.

RNA Preparation and Expression Analysis

In-vitro cultures of PF and cells in the iFA model were washed once with PBS and total RNA from the samples were extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the lung slice cultures (LSC), tissues were snap-frozen after treatment and stored at −80°C until RNA isolation. Lung slices were homogenized using a handheld homogenizer and passing the homogenate through a Qiashredder (QIAGEN). Total RNA from the LSC and cells from the disease model were extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentrations were measured on a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. Single-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 200ng of total RNA using Superscript IV and random hexamer primers (Invitrogen) in a volume of 20 μl. cDNA was then used for qRT-PCR analysis. PCR reactions were performed using Taqman Gene Expression Assay mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR reactions were performed using the StepOnePlus (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with 18S Cat. # 4331182 (Invitrogen) as housekeeping gene. For the RT2qPCR arrays, cDNA from DMSO and AA5 treated iFA and was added to the RT2 qPCR iTaq Universal SYBR green Master Mix (Biorad). 20 μL of the experimental cocktail was added to each well of the Fibrosis PCR (QIAGEN). Real-Time PCR was performed on the StepOnePlus qPCR system (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR green detection according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. All data from the PCR was collected and analyzed by SA Bioscience’s PCR Array Data Analysis Web Portal.

RNA Sequencing Analysis of Stepwise Progression, iFA (AA5) and LSC

Libraries for RNA-Seq were prepared with the Nugen human FFPE Kit (LSC). The workflow consisted of cDNA generation, end repair to generate blunt ends, adaptor ligation, adaptor cleavage and PCR amplification. Different adaptors were used for multiplexing samples in one lane. Sequencing was performed on the Illumina Nextseq500 with a single read 75 run.

iFA phenotypes from the mesenchymal-like cells (iFA model, day4 and day13), IPF whole lung tissue from the previously published data (Koyama et al., 2013) and iFA model post-AA5-prevention and AA5-resolution treatment were analyzed using the following method. The reads were aligned to the NCBI build 37.2 transcript set using Bowtie2 version 2.1.0 and TopHat version 2.0.9. TopHat’s read alignments were assembled by Cufflinks version 2.2.1. Technical replicates were combined and aligned together in all cases except for the AA5-treated model. The gene expression estimates were then log2-transformed and genes with no reads across all samples were removed from further analysis.

LSC from IPF patients treated with AA5 or DMSO for 48 hours were analyzed using the following method. Data quality check was done on Illumina SAV. Demultiplexing was performed with Illumina Bcl2fastq2 v 2.17 program. The reads were first mapped to the latest UCSC transcript set using Bowtie2 version 2.1.0 and the gene expression level was estimated using RSEM v1.2.15. TMM (trimmed mean of M-values) was used to normalize the gene expression. The gene expression estimates were then log2-transformed and genes with no reads across all samples were removed from further analysis.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

Canonical pathways GSEA (Mazzieri et al., 2000) was performed using 1,006 canonical pathways (CP) defined by the Broad Institute’s Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). Gene sets with less than 10 genes were excluded from the analysis. Published datasets from fibrotic organs were used for the comparisons to the iFA model. For calculating the normalized enrichment scores (NES), genes were ranked based on the signal-to-noise ratio. After enrichment results from the whole lung, liver and kidney tissue and iFA model were obtained, gene sets were ordered based on the average NES rank between the pairwise analyses.

The Rank Rank Hypergeometric Overlap (RRHO) Analysis

The rank rank hypergeometric overlap (RRHO) (Plaisier et al., 2010) was calculated using the web application (https://systems.crump.ucla.edu/rankrank/rankranksimple.php). The step size of 1 was used to bin the ranked items to improve the run time of calculating the hypergeometric distribution. Genes were ranked based on their differential expression in comparison groups using a log10-transformed t test P value with the sign denoting the direction of change.

Functional Network Analysis

The gene list of interest in each analysis was compiled by pairwise generating log2-transformed gene expression fold changes between AA5-treated and untreated cases. Only log2-transformed fold changes greater than −1.3 and less than 1.3 were considered significant for further analysis. From the resulting matrix, a co-expression correlation matrix was calculated, and genes were ranked based on how often they had correlation greater than 0.7. For AA5-prevention-treated (AA5-resolution-treated) iFA model 54 (82) genes upregulated and 58 (75) genes downregulated after AA5 treatment were included in the network analysis. For AA5 treated lung slice cultures 68 genes upregulated and 57 genes downregulated after AA5 treatment were included in the network analysis.

A Cytoscape plug-in ClueGo (Bindea et al., 2009) was used to visualize functionally grouped terms that contained genes from the list of interest in the form of network. The terms in Biological Processes, Cellular Component, Immune System Process and Molecular Function Gene Ontologies from February 2017 version were analyzed. Terms sharing genes were linked together into functional groups based on kappa score level ≥ 0.4. Only terms with two-sided hypergeometric p value ≤ 0.05 were kept.

In Vivo Efficacy of AA5 using murine model of ocular mucosal fibrosis

Female C56/Bl7 mice 8–10 week of age were used for all the experiments. The mice were housed in the institute’s vivarium in compliance with the Animal Research Committee. Immune-mediated conjunctivitis was induced by i.p. injection of 200 μL of immunization mix containing: 10 μg Ovalbumin (OVA) (Sigma-Aldrich), 4 mg aluminum hydroxide (Thermo Scientific), and 300 ng of pertussis toxin (Sigma-Aldrich). After 2 weeks, mice received topical OVA challenge (250 mg) once a day for 7 days for the development of fibrosis. To evaluate the efficacy of AA5 in preventing fibrosis, topical OVA challenge was accompanied by addition of 1, 10, 100 or 1000 μg/mouse (n = 12) AA5 administered in both eyes in a volume of 5 ul for a total of 7 days. To evaluate the efficacy of AA5 in resolving fibrosis, topical OVA challenge was continued for an additional 7 days (days 14–21) after the initial OVA sensitization for the development of fibrosis. From day 21 to 28, OVA challenge was accompanied by addition of 1, 10, 100 or 1000 μg/mouse (n = 12) AA5. 1% DMSO administered in both eyes in a 5 μL volume of PBS was used as control. Both eyes were scored in the same manner. For the scoring, a cumulative score of eyelid swelling (out of 3) and tearing (out of 3) was taken. At the end of the experiment at day 21 (prevention studies) or day 28 (resolution studies), mice were sacrificed and whole eyes were collected, fixed in 10% (v/v) formalin and processed by the standard methods for paraffin embedding. Sections (5 μm) were stained with Gomori Trichrome or H&E and imaged. Tissue sections were reviewed by 4 independent observers, including two observers who were blinded to the groups - a pathologist and another researcher. Conjunctivae were dissected from whole eyes and either processed for RNA or hydroxyproline assay.

In Vivo Efficacy of AA5 using murine model of pulmonary fibrosis