Abstract

Aim: It remains unclear whether elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is a risk factor for cerebral vascular disease. Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is the most appropriate model for understanding the effects of excess LDL-C because affected individuals have inherently high levels of circulating LDL-C. To clarify the effects of hypercholesterolemia on cerebral small vessel disease (SVD), we investigated cerebrovascular damage in detail due to elevated LDL-C using high resolution brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with FH.

Methods: Twenty-eight patients with FH and 35 healthy controls underwent 7T brain MRI. The prevalence of SVD and arterial structural changes were determined in each group.

Results: The prevalence of periventricular hyperintensity (PVH) was significantly higher (control, 0% vs. FH, 14.2%, p = 0.021) and deep white matter intensity tended to be more frequent in FH patients than in controls. The prevalence of SVD in patients with forms of cerebral damage, such as lacunar infarction, PVH, deep white matter hyperintensities (DWMH), microbleeding, and brain atrophy, was significantly higher among FH patients (control, n = 2, 5.7% vs. FH, n = 7, 25.0%, p < 0.001, chi-square test). The tortuosity of major intracranial arteries and the signal intensity of lenticulostriate arteries were similar in the two groups. In FH patients, as the grade of PVH progressed, several atherosclerosis risk factors, such as body mass index, blood pressure, and triglyceride level, showed ever worsening values.

Conclusion: These results obtained from FH patients revealed that persistently elevated LDL-C leads to cerebral PVH. It is necessary in the management of FH to pay attention not only to the development of coronary heart disease but also to the presence of cerebral SVD.

Keywords: Familial hypercholesterolemia, Stroke, Neuroimaging, White matter hyperintensity, LDL cholesterol

See editorial vol. 26: 1041–1042

Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder of cholesterol metabolism, resulting in serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (LDL-C) elevation1, 2). Heterozygous FH is associated with genetic defects which impair functioning of the LDL receptor, with an estimated prevalence of 1:200 to 1:500, or higher, in founder populations3) Prolonged hypercholesterolemia from birth is associated with a high incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD). In the pre-statin era, the median onset age of the first myocardial infarction was about 50 years in men and 60 years in women4). With the use of statins over the past few decades, the onset of CHD in FH has been significantly delayed, not only in European populations5) but also in the Japanese population6). The SAFEHEART registry, including 2,752 FH cases receiving lipid lowering therapies, recthatently showed a CHD prevalence in FH patients 3.3-fold higher than prevalence in their unaffected relatives7). Taken together, these observations indicate that even though statin treatment provides significant benefits, the risk of CHD remains the most serious problem in the management of patients with FH.

In contrast, the effect of LDL-C elevation on the incidence of stroke remains unclear. Generally, higher LDL-C levels are thought to be related to an increased risk of ischemic stroke8), but the contribution of these high levels is less than their contribution to the incidence of CHD9). Furthermore, the prevalence of cerebral vascular disease (CVD) in FH populations has also been a source of controversy. A previous study in the 1980s reported the incidence of brain infarction to be 20 times higher in FH patients than in the general population10, 11). On the other hand, several studies have shown no association between incidence of ischemic stroke and FH12–14). The SAFEHEART registry also showed the prevalence of CVD to be similar in FH patients and their unaffected relatives7).

Subclinical ischemic brain damage was examined using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in asymptomatic FH patients. These examinations demonstrated brain abnormalities, such as deep white matter hyperintensities (DWMH), as not differing between FH and control patients15–17). Unfortunately, these studies lacked information on the prevalence of small vessel disease (SVD), including lacuna infarctions, microbleeds, and brain atrophy, and the microvasculature was not analyzed in detail by magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). The findings of these prior studies in the current statin era have indicated that the incidence of CVD is approximately the same, possibly somewhat higher, in FH patients as it is in the general population and, furthermore, that important issues remain to be resolved18).

Ultra-high-field 7.0 Tesla (7T) MRI provides an increased signal-to-noise ratio of the inflow signal at high spatial resolution19), enabling us to investigate characteristics of the microvasculature, including the structure of lenticulostriate arteries (LSA)20). To investigate details of the cerebrovascular damage associated with high LDL-C levels, we projected this imaging analysis study using high resolution brain MRI on Japanese FH patients.

Methods

Study Subjects

The study subjects were 28 FH patients with no past history of CHD visiting the Iwate Medical University Hospital during the period from October 2016 to December 2017. FH was defined according to the diagnostic criteria proposed by the Japan Atherosclerosis Society21), i.e., high values of LDL-C, presence of xanthomas and family history of hypercholesterolemia or early onset CHD, or identification of abnormalities in genes related to LDL-C metabolism. Thirty-five metabolically healthy local volunteers were enrolled as age-matched controls. The exclusion criteria applied to assure “metabolically healthy” status were hyperglycemia, high blood pressure and lipid profile abnormalities at the most recent medical check-up, and past history of diabetes and/or hypertension and/or dyslipidemia. None of the study patients in either group had any history of CHD or CVD. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Iwate Medical University (Approval number: H26-104).

MR Protocols

We used a 7T MRI scanner (Discovery MR950; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) with quadrature transmission and a 32-channel receive head coil. High resolution time-of-flight MRA was acquired using a three-dimensional (3D) spoiled gradient recalled echo sequence with the following scanning parameters: repetition time (TR) 12 ms; echo time (TE) 2.4 ms; flip angle (FA) 12°; field of view (FOV) 240 mm; acquisition matrix size 768 × 384; reconstructed matrix size 1024 × 1024; slice thickness 0.3 mm (after zero-fill interpolation); number of slices 352; and acquisition time 10 min 26 s. Conventional brain MRI, such as obtaining T1-weighted, T2*-weighted, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, was also performed22).

Data Analysis

The maximum intensity projection (MIP) images obtained by MRA, including the anterior and middle cerebral arteries focused on LSA, were reconstructed at the oblique coronal planes parallel to the LSA (thickness, 20 mm; interval, 1.0 mm; partitions, 45) with a 90 mm FOV, and at the axial planes (thickness, 2 mm; interval, 0.5 mm; partitions, 92) and the bilateral sagittal (thickness, 20 mm; interval, 0.6 mm; partitions, 40) planes with a 100 mm FOV22, 23). All reformatting of images was performed by one of the authors (I.U.) using a commercially available workstation (Advantage Workstation 4.5; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI).

To delineate LSA distributions, we overlaid line tracings that were based on the 3D LSA images onto the conventional two-dimensional MIP images. By using these images, the morphological characteristics of LSA, including stems, branches, length, and tortuosity, for comparison between FH patients, and controls were analyzed using Vox-base II (J-MAC SYSTEM, Inc., Japan), as previously reported23).

A board certified senior radiologist (MS, with more than 20 years of experience), blinded to the clinical status of the patients, visually evaluated all images twice each for the presence of any abnormalities. This radiologist concurrently determined narrowing or interruption of the LSA, as indicated by a decrease in signal intensity on the MRA-MIP images due to reduced blood flow, findings collectively referred to as “impaired LSA visualization”23). Conventional brain MRI was used to evaluate DWMH and periventricular hyperintensity (PVH) of Fazekas grade II or III, lacunar infarctions, brain atrophy, and microbleeds. Patients with one or more of these findings were defined as having SVD.

Measurements of baPWV and Carotid Artery IMT

The brachial ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) was measured using an automatic waveform analyzer (BP-203RPE; Colin Co., Komaki, Japan). The intima-media thickness (IMT) of the carotid arteries was measured using ultrasound diagnostic equipment (LOGIQ 500, GE Yokogawa Medical Systems Corp., Hino, Tokyo, Japan) and the max IMT, i.e., the thickest portion detected in the scanned regions, was measured as described previously24).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) or as medians with interquartile range (IQR) when the data showed a non-normal distribution. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Comparisons between the patient groups were performed employing the student t-test and the chi-square test or, when the data showed a non-normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U-test. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 21 (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Results

The clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients, both the FH and the control group, are shown in Table 1. The averages of LDL-C, total cholesterol (TC), systolic blood pressure (sBP), body mass index (BMI), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were significantly higher in the FH group than they were in the control group. Ages were similar in the two groups. In FH patients, the average Achilles tendon thickness was 9.22 ± 3.31 mm and the average pretreatment LDL-C value was 234.5 ± 52.3 mg/dL. All but one of the FH patients had a first-degree family history of hypercholesterolemia. Four patients had been diagnosed based on identification of a mutation in the LDL receptor gene or pro-protein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9). Twenty-two FH patients (78.5%) were treated with statins, six (21.4%) with ezetimibe and two (7.1%) with a PCSK9 inhibitor. No patients were administered drugs for either hypertension or diabetes.

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Subjects.

| control (n = 35) | FH (n = 28) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 45.2 ± 7.6 | 49.1 ± 15.3 | 0.312 |

| Male/Female | 19/16 | 9/19 | 0.078 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.8 ± 2.6 | 23.4 ± 2.7 | 0.026 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 113.6 ± 12.2 | 127.4 ± 17.4 | < 0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 72.5 ± 8.4 | 74.5 ± 7.8 | 0.295 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 111.5 (94–120) | 134.5 (120–161) | < 0.01 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 68.1 ± 15.3 | 64.0 ± 14.0 | 0.274 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 191.6 ± 24.8 | 235.3 ± 42.2 | < 0.01 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 72.5 (57.8–105.8) | 108.0 (76–123.8) | 0.111 |

| AST (U/L) | 20 (17–22) | 23.5 (19–25.5) | 0.056 |

| ALT (U/L) | 16.5 (13–22) | 23 (18–34) | < 0.01 |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 24.5 (16–38.5) | 18 (16–29) | 0.295 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.40 ± 0.28 | 5.56 ± 0.31 | 0.022 |

| Achilles tendon thickness (mm) | - | 9.22 ± 3.31 | - |

| Statin users (n) | - | 22 | - |

| Duration of Statin use (months) | - | 28.5 (17–108) | - |

| Ezetimibe users (n) | - | 6 | - |

| PCSK9 inhibitor (n) | - | 2 | - |

| No lipid lowering agent (n) | - | 3 | - |

Values are Means ± SD, Median (IQR)

AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, γ-GTP: γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TC: total cholesterol, TG: triglyceride

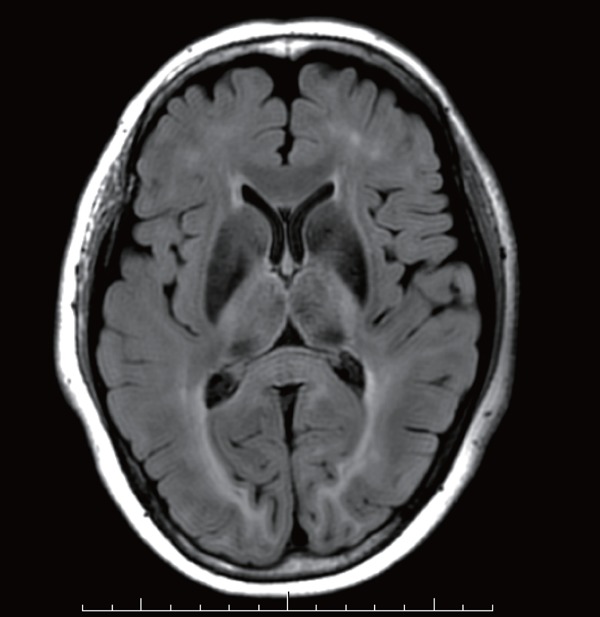

The results of the high resolution brain MRI analysis are shown in Table 2. No patient in either group had lacunar infarctions and/or microbleeds. The prevalence of DWMH tended to be higher in the FH group (n = 6, 21.4%) than in the control (n = 2, 5.6%) group. The prevalence of PVH, suggesting ischemic brain damage as well as DWMH, was significantly higher in the FH group than it was in the control group (control, 0% vs. FH, 14.2%, p = 0.021). Fig. 1 shows a representative FLAIR image of PVH in a patient with FH. The prevalence of SVD patients with cerebral damage, such as lacunar infarction, PVH, DWMH, microbleeding, and/or brain atrophy, was significantly higher among the FH patients than it was among the controls (control, n = 2, 5.7% vs. FH, n = 7, 25.0%, p < 0.001, chi-square test).

Table 2. Prevalence of cerebrovascular findings.

| control (n = 35) | FH (n = 28) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1W1/FLAIR | |||

| Lacunar infarction | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| PVH | 0 (0%) | 4 (14.2%) | 0.021 |

| DWMH | 2 (5.6%) | 6 (21.4%) | 0.063 |

| Atrophy | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.5%) | 0.259 |

| SWI | |||

| CMBs | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| MRA | |||

| Major tortuous artery | 2 (5.7%) | 2 (7.1%) | 0.395 |

| LSA visual impairment | 12 (34.2%) | 9 (32.1%) | 0.857 |

Analyzed by χ-square test

PVH: periventricular hyperintensity, DWMH: deep white matter hyperintensity, CMBs: cerebral microbleeds, LSA: lenticulostriate arteries

Fig. 1.

Axial FLAIR image with numerous areas of nonspecific PVH in a 52 year old female with FH.

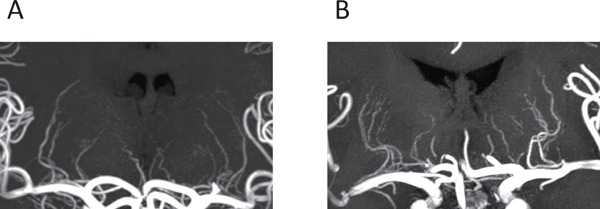

High resolution MRA clearly visualized bilateral LSA (Fig. 2) as well as large intracranial arteries in both groups. The tortuosity of major intracranial arteries was similar in the two groups (Table 2). The prevalence of this impaired LSA visualization did not differ between the two groups, as is shown in Table 2. A detailed investigation of LSA structural changes, such as numbers of stems and branches, length, and tortuosity, revealed no marked differences between the two groups (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Representative 7T MRA images of the LSA in controls (A) and FH (B)

Table 3. Comparison of LSA characteristics.

| control (n = 35) | FH (n = 28) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| stems (number) | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 6.4 ± 1.5 | 0.133 |

| branches (number) | 3.4 ± 2.2 | 4.1 ± 3.0 | 0.368 |

| length (mm) | 27.7 ± 6.0 | 25.5 ± 3.9 | 0.138 |

| tortuosity | 1.32 ± 0.10 | 1.31 ± 0.09 | 0.664 |

Values are Means ± SD

Analyzed by student t-test

Next, to identify the variables affecting ischemic brain damage in FH, we compared clinical parameters between subgroups which were divided according to the grade of PVH (Table 4). The patients with PVH of Fazekas grade II were significantly older than were those with grade 0 or grade I. Long-term statin administration in the patients with Fazekas grade II PVH might reflect advanced age. As the grade of PVH progressed, several atherosclerosis risk factors, such as BMI, blood pressure, and triglyceride (TG) levels, showed ever worsening values. Predictably, established surrogate markers of atherosclerosis, IMT, and pulse wave velocity (PWV) were closely associated with the progression of PVH in FH patients. Taking these observations together, we considered the risk factors for minimal cerebral ischemic change in our FH patients to be consistent with well-established risk factors in the general population, such as advanced age, high blood pressure, and obesity15).

Table 4. Comparison of clinical characteristics between subgroups based on PVH in FH.

| PVH | Grade0 (n = 9) | Grade1 (n = 15) | Grade2 (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.8 ± 12.8 | 51.2 ± 14.1 | 64.8 ± 4.3††** |

| BMI | 21.7 ± 2.3 | 23.8 ± 1.9 | 25.8 ± 3.3 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 116.7 ± 9.1 | 131.7 ± 17.9 | 135.0 ± 17.2 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73.4 ± 5.5 | 74.5 ± 8.0 | 76.0 ± 10.4 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 149 (146–161) | 125 (116–149) | 136.5 (129–159) |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 58.8 ± 11.3 | 67.3 ± 15.3 | 63.0 ± 9.3 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 240.6 ± 38.8 | 229.7 ± 45.1 | 244.5 ± 27.4 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 89 (66–112) | 108 (82.5–123) | 131.5 (94.8–180) |

| AST (U/L) | 19 (16–23) | 24 (20–30) | 24 (23–25) |

| ALT (U/L) | 21 (17–29) | 29 (17.5–41.5) | 22 (21.5–25) |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 16 (14–21) | 26 (17–56) | 16.5 (15.5–30) |

| Cre (mg/dl) | 0.71 ± 0.19 | 0.75 ± 0.11 | 0.74 ± 0.09 |

| Achilles tendon thickness (mm) | 8.89 ± 2.51 | 9.50 ± 2.92 | 9.25 ± 5.07 |

| Duration of Statin use (months) | 14 (0–28) | 25 (9–96) | 138 (36–258)† |

| Max IMT (mm) | 0.99 ± 0.61 | 1.38 ± 0.37 | 2.22 ± 0.46†** |

| PWV (cm/sec) | 1128 ± 78 | 1408 ± 269* | 1630 ± 219†† |

Analyzed by Tukey test or Dunnett test

p < 0.05 Grade0 vs Grade1,

p < 0.05 Grade0 vs Grade2,

p < 0.01 Grade0 vs Grade2,

p < 0.05 Grade1 vs Grade2

Discussion

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine cerebral SVD and cerebrovascular changes using MRI in a small group of Japanese patients with FH. Our imaging analysis revealed a high prevalence of ischemic cerebral change in asymptomatic FH subjects as compared with healthy controls, suggesting that LDL-C plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of CVD.

Several cohort studies have demonstrated cholesterol to make only a small contribution to the incidence of ischemic stroke. A meta-analysis of individual datasets from 61 prospective studies conducted in western countries showed no association between the TC level and the mortality rate from CVD25). In addition, a meta-analysis of studies conducted in Japan and China showed a major contribution of blood pressure to the incidence of CVD, with the contribution of TC being much smaller26). In terms of the relationship between LDL-C and ischemic stroke, the Women's Health Study showed a positive correlation27), while the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study showed no significant correlation28). In the Hisayama Study conducted in Japan, the serum LDL-C level was found to be a significant risk factor for atherothrombotic stroke8). On the other hand, it is well-known that statin treatment markedly reduces the risk of ischemic stroke, probably due to a vascular protective mechanism as well as to the LDL-C lowering effects29).

To understand the effects of excess LDL-C, FH is the most appropriate model because of the inherently high levels of circulating LDL-C in these patients. A prospective registry study of individuals with FH from England found the risk of fatal stroke in FH to not be increased as compared with controls14). Similarly, a cohort registry of Spanish FH patients showed similar CVD incidences, though not of CHD and peripheral artery disease, in FH patients and their unaffected relatives7). A Mendelian randomization analysis recently revealed FH and high LDL-C to not confer an increased risk of ischemic stroke30). In addition, previous imaging analyses using MRI showed that the prevalence of CVD, including small infarctions, DWMH, and lacunar infarctions, was similar in FH and control patients15–17, 31). Judging from cohort studies and imaging analyses, cerebral ischemic change appears to be mild in FH patients, suggesting LDL-C to have a minimal impact on cerebral vascular damage.

On the other hand, the pathogenic concept of LDL-induced atherosclerosis development, including foam cell formation32), inflammatory response, and endothelial dysfunction33), might be relevant to cerebral arteries as well as to coronary arteries. In fact, our imaging analysis revealed the prevalence of PVH to be significantly higher and that of DWMH to show an increasing tendency in FH as compared with control patients. Considering the pathological effects of LDL-C on arteriosclerosis, our results can be regarded as reasonable. In this study, sBP, BMI, and ALT, which have been implicated in the exacerbation of cerebral atherosclerosis, were significantly higher in FH than in control patients. However, these parameters remained within normal ranges in both groups, suggesting minor impacts on the prevalence of PVH and DWMH. One of the reasons for the differences between our results and those of previous studies18) is considered to be the duration of statin administration. The diagnostic yield for FH is reportedly low in Japan as compared with western countries34), resulting in delayed initiation of statin administration. In this study, nearly all enrolled FH patients were being treated with a statin or with another lipid lowering agent. However, 11 patients had recently been diagnosed as having FH, such that their durations of statin treatment were quite short. FH patients, who received long-term statin treatment (15 years) did not have more DWMH on brain MRI than healthy controls17). In contrast to this previous report17), the median duration of statin administration was 26 months in our FH patients, indicating insufficient time for the beneficial effects of statin treatment to be exerted. In other words, our results more accurately reflected the native features, i.e., independently of statin effects, of cerebral atherosclerosis in FH patients. Racial differences might be involved in the high prevalence of PVH in FH patients in our study. Ischemic stroke accounts for a large portion of atherosclerotic disease cases in Japan as compared with western countries35). Thus, the impacts of LDL-C on cerebral vascular damage may differ among races. Finally, advancements in MRI and image analysis in the present decade, i.e., high resolution 7T MRI, may also contribute to more accurate detection of SVD.

Aging is the strongest risk factor for SVD progression in FH. In addition, in the small group analysis, blood pressure, BMI, and TG values tended to rise in accordance with PVH grade. These well-established risk factors for atherosclerosis development were just as applicable to FH patients as they were to the general population. Furthermore, established surrogate markers, such as IMT and PWV measurements, were associated with the prevalence of PVH. Taking these preliminary observations together, we hypothesized that the risk of PVH in FH, as is the case for general populations, might be predictable by evaluating common risk factors and/or physiological features of atherosclerosis.

PVH and DWMH are both regarded as risk factors for cognitive impairment36). Meanwhile, FH patients had a higher incidence of mild cognitive impairment, which is considered to be a result of long-term hypercholesterolemia37), an observation made even in young patients38). Therefore, as an aspect of managing cognitive impairment, evaluation of cerebral SVD has become an important issue in FH. Long-term statin treatment may well be associated with better episodic memory39), indicating the benefits of early statin administration to FH patients.

The major limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, raising the possibility that our results show only associations. The relationship between the prevalence of SVD and ischemic stroke development in FH patients needs to be confirmed in a further longitudinal study. Secondly, clinical backgrounds of the FH patients were variable in terms of age, duration of statin administration, and medication types. The broad ranges in age and period of statin treatment affected cerebral vascular conformation and also introduced statistical bias. Most of the enrolled FH patients had not been diagnosed based on genetic analysis, instead meeting the diagnostic criteria proposed by the Japan Atherosclerosis Society2). Finally, our sample size was too small to allow sufficiently powered statistical analyses to be performed. Therefore, our data are not definitive but, rather, represent a preliminary result. Most notably, the number of patients in a comparative analysis of clinical characteristics between subgroups based on PVH, as is shown in Table 4, was unbalanced and extremely small. Additionally, this study lacked multivariate analysis due to the small sample size, suggesting the obtained results to potentially have an unconscious bias. Thus, further examination with larger numbers of FH patients is needed to confirm our findings.

In conclusion, the results obtained from FH patients revealed long-term LDL-C elevation to be associated with cerebral PVH formation. In the management of FH, it is necessary to pay attention to not only the development of CHD, but also to the presence of cerebral SVD.

Acknowledgments

The authors' contributions are as follows; Y.T. recruited the patients, collected the data and wrote the manuscript; S.Y., K.N, A.C., T.O., H.H., and Y. T. designed the study and conducted the statistical analysis. Y.H. reviewed and edited the manuscript; I.U. and MS performed the MRI examinations and radiological analyses; Y.I. managed the study, contributed to relevant discussions, and reviewed the manuscript.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (15K09416), to Y.I., from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and a Grant-in-Aid for Strategic Medical Science Research (S1491001, 2014–2018) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1). Mabuchi H: Half a Century Tales of Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH) in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2017; 24: 189-207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Harada-Shiba M, Arai H, Ishigaki Y, Ishibashi S, Okamura T, Ogura M, Dobashi K, Nohara A, Bujo H, Miyauchi K, Yamashita S, Yokote K: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Familial Hypercholesterolemia 2017. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2018; 25: 751-770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Mabuchi H, Nohara A, Noguchi T, Kobayashi J, Kawashiri MA, Inoue T, Mori M, Tada H, Nakanishi C, Yagi K, Yamagishi M, Ueda K, Takegoshi T, Miyamoto S, Inazu A, Koizumi J: Genotypic and phenotypic features in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia caused by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) gain-of-function mutation. Atherosclerosis, 2014; 236: 54-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Stone NJ, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS, Verter J: Coronary artery disease in 116 kindred with familial type II hyperlipoproteinemia. Circulation, 1974; 49: 476-488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Versmissen J, Oosterveer DM, Yazdanpanah M, Defesche JC, Basart DC, Liem AH, Heeringa J, Witteman JC, Lansberg PJ, Kastelein JJ, Sijbrands EJ: Efficacy of statins in familial hypercholesterolaemia: a long term cohort study. BMJ, 2008; 337: a2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Harada-Shiba M, Sugisawa T, Makino H, Abe M, Tsushima M, Yoshimasa Y, Yamashita T, Miyamoto Y, Yamamoto A, Tomoike H, Yokoyama S: Impact of statin treatment on the clinical fate of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2010; 17: 667-674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Perez de Isla L, Alonso R, Mata N, Saltijeral A, Muniz O, Rubio-Marin P, Diaz-Diaz JL, Fuentes F, de Andres R, Zambon D, Galiana J, Piedecausa M, Aguado R, Mosquera D, Vidal JI, Ruiz E, Manjon L, Mauri M, Padro T, Miramontes JP, Mata P: Coronary Heart Disease, Peripheral Arterial Disease, and Stroke in Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: Insights From the SAFEHEART Registry (Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Cohort Study). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2016; 36: 2004-2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Imamura T, Doi Y, Arima H, Yonemoto K, Hata J, Kubo M, Tanizaki Y, Ibayashi S, Iida M, Kiyohara Y: LDL cholesterol and the development of stroke subtypes and coronary heart disease in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Stroke, 2009; 40: 382-388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Okamura T, Tanaka H, Miyamatsu N, Hayakawa T, Kadowaki T, Kita Y, Nakamura Y, Okayama A, Ueshima H: The relationship between serum total cholesterol and all-cause or cause-specific mortality in a 17.3-year study of a Japanese cohort. Atherosclerosis, 2007; 190: 216-223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Kaste M, Koivisto P: Risk of brain infarction in familial hypercholesterolemia. Stroke, 1988; 19: 1097-1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Bansal BC, Sood AK, Bansal CB: Familial hyperlipidemia in stroke in the young. Stroke, 1986; 17: 1142-1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Mabuchi H, Miyamoto S, Ueda K, Oota M, Takegoshi T, Wakasugi T, Takeda R: Causes of death in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis, 1986; 61: 1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Hutter CM, Austin MA, Humphries SE: Familial hypercholesterolemia, peripheral arterial disease, and stroke: a HuGE minireview. Am J Epidemiol, 2004; 160: 430-435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Huxley RR, Hawkins MH, Humphries SE, Karpe F, Neil HA: Risk of fatal stroke in patients with treated familial hypercholesterolemia: a prospective registry study. Stroke, 2003; 34: 22-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Soljanlahti S, Autti T, Lauerma K, Raininko R, Keto P, Turtola H, Vuorio AF: Familial hypercholesterolemia patients treated with statins at no increased risk for intracranial vascular lesions despite increased cholesterol burden and extracranial atherosclerosis. Stroke, 2005; 36: 1572-1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Schmitz SA, O'Regan DP, Fitzpatrick J, Neuwirth C, Potter E, Tosi I, Hajnal JV, Naoumova RP: White matter brain lesions in midlife familial hypercholesterolemic patients at 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Radiol, 2008; 49: 184-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Hyttinen L, Autti T, Rauma S, Soljanlahti S, Vuorio AF, Strandberg TE: White matter hyperintensities on T2-weighted MRI images among DNA-verified older familial hypercholesterolemia patients. Acta Radiol, 2009; 50: 320-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Barkas F, Elisaf M, Milionis H: Statins decrease the risk of stroke in individuals with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis, 2015; 243: 60-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Sato Y, Ogasawara K, Yoshida K, Sasaki M: Preoperative visualization of the marginal tentorial artery as an unusual collateral pathway in a patient with symptomatic bilateral vertebral artery occlusion undergoing arterial bypass surgery: A 7.0-T magnetic resonance imaging study. Surg Neurol Int, 2014; 5: 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Natori T, Sasaki M, Miyoshi M, Ohba H, Oura MY, Narumi S, Harada T, Kabasawa H, Terayama Y: Detection of vessel wall lesions in spontaneous symptomatic vertebrobasilar artery dissection using T1-weighted 3-dimensional imaging. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 2014; 23: 2419-2424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, Birou S, Daida H, Dohi S, Egusa G, Hiro T, Hirobe K, Iida M, Kihara S, Kinoshita M, Maruyama C, Ohta T, Okamura T, Yamashita S, Yokode M, Yokote K, Harada-Shiba M, Arai H, Bujo H, Nohara A, Ohta T, Oikawa S, Okada T, Wakatsuki A: Familial hypercholesterolemia. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2014; 21: 6-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Uwano I, Kudo K, Yamashita F, Goodwin J, Higuchi S, Ito K, Harada T, Ogawa A, Sasaki M: Intensity inhomogeneity correction for magnetic resonance imaging of human brain at 7T. Med Phys, 2014; 41: 022302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Yashiro S, Kameda H, Chida A, Todate Y, Hasegawa Y, Nagasawa K, Uwano I, Sasaki M, Ogasawara K, Ishigaki Y: Evaluation of Lenticulostriate Arteries Changes by 7 T Magnetic Resonance Angiography in Type 2 Diabetes. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2018; 25: 1067-1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Hangai M, Takebe N, Honma H, Sasaki A, Chida A, Nakano R, Togashi H, Nakagawa R, Oda T, Matsui M, Yashiro S, Nagasawa K, Kajiwara T, Takahashi K, Takahashi Y, Satoh J, Ishigaki Y: Association of Advanced Glycation End Products with coronary Artery Calcification in Japanese Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes as Assessed by Skin Autofluorescence. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2016; 23: 1178-1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R: Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet, 2007; 370: 1829-1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Blood pressure, cholesterol, and stroke in eastern Asia. Eastern Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease Collaborative Research Group. Lancet, 1998; 352: 1801-1807 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Kurth T, Everett BM, Buring JE, Kase CS, Ridker PM, Gaziano JM: Lipid levels and the risk of ischemic stroke in women. Neurology, 2007; 68: 556-562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Psaty BM, Anderson M, Kronmal RA, Tracy RP, Orchard T, Fried LP, Lumley T, Robbins J, Burke G, Newman AB, Furberg CD: The association between lipid levels and the risks of incident myocardial infarction, stroke, and total mortality: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2004; 52: 1639-1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R: Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet, 2005; 366: 1267-1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Beheshti S, Madsen CM, Varbo A, Benn M, Nordestgaard BG: Relationship of Familial Hypercholesterolemia and High Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol to Ischemic Stroke. Circulation, 2018; 138: 578-589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Soljanlahti S, Raininko R, Hyttinen L, Lauerma K, Keto P, Vuorio AF, Autti T: Statin-treated familial hypercholesterolemia patients with coronary heart disease and pronounced atherosclerosis do not have more brain lesions than healthy controls in later middle age. Acta Radiol, 2007; 48: 894-899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Steinberg D: Atherogenesis in perspective: hypercholesterolemia and inflammation as partners in crime. Nat Med, 2002; 8: 1211-1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Ross R: Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med, 1999; 340: 115-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, Ginsberg HN, Masana L, Descamps OS, Wiklund O, Hegele RA, Raal FJ, Defesche JC, Wiegman A, Santos RD, Watts GF, Parhofer KG, Hovingh GK, Kovanen PT, Boileau C, Averna M, Boren J, Bruckert E, Catapano AL, Kuivenhoven JA, Pajukanta P, Ray K, Stalenhoef AF, Stroes E, Taskinen MR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A: Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J, 2013; 34: 3478-3490a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Suzuki K, Sarti C, Tuomilehto J, Kutsuzowa T, Narva EV, Sivenius J, Salmi K, Kaarsalo E, Torppa J, Kuulasmaa K: Stroke incidence and case fatality in Finland and in Akita, Japan: a comparative study. Neuroepidemiology, 1994; 13: 236-244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Vermeer SE, Hollander M, van Dijk EJ, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM: Silent brain infarcts and white matter lesions increase stroke risk in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke, 2003; 34: 1126-1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Zambon D, Quintana M, Mata P, Alonso R, Benavent J, Cruz-Sanchez F, Gich J, Pocovi M, Civeira F, Capurro S, Bachman D, Sambamurti K, Nicholas J, Pappolla MA: Higher incidence of mild cognitive impairment in familial hypercholesterolemia. Am J Med, 2010; 123: 267-274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Ariza M, Cuenca N, Mauri M, Jurado MA, Garolera M: Neuropsychological performance of young familial hypercholesterolemia patients. Eur J Intern Med, 2016; 34: e29-e31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Hyttinen L, TuulioHenriksson A, Vuorio AF, Kuosmanen N, Harkanen T, Koskinen S, Strandberg TE: Longterm statin therapy is associated with better episodic memory in aged familial hypercholesterolemia patients in comparison with population controls. Journal of Alzheimer's disease: JAD, 2010; 21: 611-617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]