Abstract

Aims

To date, clinical evidence of microvascular dysfunction in patients with heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) has been limited. We aimed to investigate the prevalence of coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) and its association with systemic endothelial dysfunction, HF severity, and myocardial dysfunction in a well defined, multi-centre HFpEF population.

Methods and results

This prospective multinational multi-centre observational study enrolled patients fulfilling strict criteria for HFpEF according to current guidelines. Those with known unrevascularized macrovascular coronary artery disease (CAD) were excluded. Coronary flow reserve (CFR) was measured with adenosine stress transthoracic Doppler echocardiography. Systemic endothelial function [reactive hyperaemia index (RHI)] was measured by peripheral arterial tonometry. Among 202 patients with HFpEF, 151 [75% (95% confidence interval 69–81%)] had CMD (defined as CFR <2.5). Patients with CMD had a higher prevalence of current or prior smoking (70% vs. 43%; P = 0.0006) and atrial fibrillation (58% vs. 25%; P = 0.004) compared with those without CMD. Worse CFR was associated with higher urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) and NTproBNP, and lower RHI, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, and right ventricular (RV) free wall strain after adjustment for age, sex, body mass index, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, revascularized CAD, smoking, left ventricular mass, and study site (P < 0.05 for all associations).

Conclusions

PROMIS-HFpEF is the first prospective multi-centre, multinational study to demonstrate a high prevalence of CMD in HFpEF in the absence of unrevascularized macrovascular CAD, and to show its association with systemic endothelial dysfunction (RHI, UACR) as well as markers of HF severity (NTproBNP and RV dysfunction). Microvascular dysfunction may be a promising therapeutic target in HFpEF.

Keywords: Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, Coronary microvascular dysfunction, Coronary flow reserve, Endothelial dysfunction, Echocardiography, Biomarkers

Introduction

Coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) has been proposed to be a novel mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)1–5—the dominant form of HF for which no treatment has yet been proven to reduce morbidity and mortality.6 Paulus and Tschope5 hypothesized that comorbidities common to HFpEF (e.g. obesity, diabetes, chronic kidney disease) lead to systemic inflammation and coronary endothelial inflammation and CMD, which reduces endothelial nitric oxide bioavailability and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) production by adjacent cardiomyocytes. This process results in downstream titin hypophosphorylation and increased cardiomyocyte stiffening, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, myofibroblast activation, and interstitial fibrosis. Both cardiomyocyte and extracellular mechanisms lead to increased left ventricular (LV) diastolic stiffening, a known hallmark of the HFpEF syndrome.7

Coronary microvascular dysfunction could also explain other deleterious effects in HFpEF such as exercise-induced myocardial ischaemia, subendocardial LV systolic dysfunction,8–10 and poor cardiac systolic and diastolic reserve.11,12 Several preclinical studies support the hypothesis that CMD plays a key role in HFpEF pathogenesis.1,4,13–17 However, clinical evidence of CMD in HFpEF has been largely indirect and limited to relatively small prospective studies or retrospective studies involving convenience samples referred for nuclear imaging for the evaluation of coronary artery disease (CAD).16–20 Exercise studies implicate vascular stiffness and impaired exercise vasodilation and suggest that impaired diastolic reserve may be related to endothelial and microvascular dysfunction.12 An autopsy study provided convincing evidence of coronary microvascular rarefaction in HFpEF.4 While supportive of the presence of CMD in HFpEF, the prevalence of CMD in HFpEF remains unknown, and the clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic correlates of CMD in HFpEF have not been adequately studied. Understanding the factors associated with CMD in HFpEF could provide insight into the pathogenesis of HFpEF and may help inform the design of future clinical trials of pharmacotherapies designed to ameliorate CMD in HFpEF.

We, therefore, designed a prospective, multi-centre, multinational study of CMD in HFpEF using a comprehensive functional imaging approach combining detailed echocardiography and adenosine-based transthoracic Doppler echocardiography-assessed coronary flow reserve (CFR) measurement [PRevalence Of MIcrovascular dySfunction in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (PROMIS-HFpEF)]. The key goals of the study were to evaluate (i) the prevalence of impaired CFR in HFpEF; and (ii) potential correlates of reduced CFR in HFpEF, including systemic endothelial dysfunction, clinical factors, laboratory markers, and echocardiographic indices.

Methods

PROMIS-HFpEF study design

Between December 2015 and January 2018, patients with a confirmed diagnosis of chronic HFpEF who met pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Supplementary material online) were prospectively enrolled at five centres [Karolinska Institute (Stockholm, Sweden); Sahlgrenska University Hospital (Gothenburg, Sweden); Turku University Hospital (Turku, Finland); Northwestern Memorial Hospital (Chicago, USA); and National Heart Centre Singapore (Singapore)]. Major inclusion criteria included a prior history of symptomatic HF, stable New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II–IV symptoms on the most recent clinic visit, ejection fraction (EF) ≥40%, and at least one of the following criteria: (i) elevated natriuretic peptides; (ii) prior HF hospitalization with evidence of either LV hypertrophy or left atrial (LA) enlargement; (iii) elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure at rest or with exercise; or (iv) E/e′ ratio >15. All patients underwent evaluation for epicardial CAD according to current guidelines. In patients who had suspected ischaemic heart disease, stress testing and/or coronary angiography was performed to exclude significant epicardial CAD. Patients with known unrevascularized macrovascular CAD were excluded. All study participants gave written informed consent, and the institutional review board at each of the participating sites approved the study. The PROMIS study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study procedures included a history and physical examination; fasting blood and urine testing; 6-min walk test (6MWT); EndoPAT (peripheral arterial tonometry) testing; Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ21); comprehensive echocardiography; and Doppler echocardiography measurement of left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery flow velocity at rest and during adenosine infusion. The Supplementary material online contains the collected clinical characteristics, laboratory tests, definitions of comorbidities, and a description of EndoPAT testing.

Echocardiography

All study participants underwent comprehensive two-dimensional echocardiography with Doppler and tissue Doppler imaging using commercially available ultrasound systems with harmonic imaging (Vivid 7 or Vivid E9, GE Healthcare, General Electric Corp., Waukesha, WI, USA). The test was performed with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position. Blood pressure was recorded at the time of echocardiography using a digital blood pressure monitor with a brachial cuff. Cardiac structure and function were quantified as recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography/European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging22–26; non-invasive pressure-volume analysis was performed using echocardiographic and blood pressure data27; and speckle-tracking analysis of the echocardiograms was performed as described previously.8 The echocardiography methods are further detailed in the Supplementary material online.

Measurement of coronary flow reserve

A dedicated research sonographer from each study site underwent a centralized, in-person, intensive 1 week training and standardization programme at Sahlgrenska University Hospital for the acquisition of LAD Doppler flow signals at rest and during adenosine infusion. Coronary flow reserve testing was performed using a previously published and validated protocol.28 Briefly, the mid-to-distal portion of the LAD coronary artery was identified using high-resolution (3.0–3.5 MHz) colour Doppler in the interventricular sulcus in a modified apical two-chamber view. Pulse wave Doppler was used to sample flow velocity signals at rest and during adenosine infusion (140 μg/min/kg) over 5–10 min. During the entire procedure, blood pressure and electrocardiography (ECG) were monitored. All studies were digitally stored for offline reviewing and measurements. Coronary flow velocity data were analysed offline using the ultrasound software Image Arena (TOMTEC, Unterschleißheim, Germany). Mean diastolic flow velocity at baseline and during peak hyperaemia was measured by manual tracing of the diastolic Doppler flow signals. Baseline coronary flow velocities were calculated by using the mean value of three representative cardiac cycles. The mean hyperaemic coronary flow velocity during adenosine infusion was calculated as the mean of the three highest values. For patients with atrial fibrillation, 10 beats were averaged at both rest and during hyperaemia. Coronary flow reserve was calculated as the ratio between the hyperaemic and baseline mean coronary flow velocity values. A coronary flow velocity ratio of <2.5 was defined as reduced and diagnostic of CMD based on prior studies that have established Doppler-based CFR <2.5 as the optimal threshold.29 However, given the continuum of risk associated with reduction in CFR (without a specific threshold) in other cardiovascular syndromes, we also examined CFR as a continuous variable (see Statistical Analysis section). All CFR measurements were performed by a single, blinded investigator at an experienced core laboratory at Sahlgrenska University Hospital (Sahlgrenska, Sweden). Details regarding the validation and feasibility of the echocardiography Doppler-based CFR measurement are provided in the Supplementary material online.

Statistical analysis

Using CFR <2.5 as a cut-off to define CMD, we first calculated the prevalence and 95% confidence interval (CI) of CMD in the enrolled HFpEF patients. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Heart Failure Association Pre-test probability, Echocardiography, Further advanced work-up, and Final etiology (HFA-PEFF) score—a tool based on echocardiographic and natriuretic peptide data, created to verify the diagnosis of HFpEF—was calculated for all patients. Next, we divided the PROMIS-HFpEF study participants into those with vs. without CMD and compared clinical characteristics, laboratory data, and echocardiographic measures. We used the t-test (or non-parametric equivalent, when indicated) and the χ2 test (or the Fisher’s exact test, when indicated) to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

We used multivariable linear regression (using CFR as the dependent variable) to identify the clinical correlates of CMD. We also used unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted linear regression analyses [using KCCQ, 6MWT, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR), NTproBNP, and various echocardiographic parameters as the dependent variable in each model] to determine the independent association between CFR and these variables. Covariates were selected on a basis of clinical relevance and known association with CMD. We also included study site as a covariate in all multivariable analyses. Covariates included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), atrial fibrillation, diabetes, CAD, LV mass, and E/e′ ratio. Formal interaction testing with multiplicative interaction terms was used to determine whether certain study (site) or clinical (age, sex, atrial fibrillation, and BMI) characteristics modified the identified factors associated with CMD in the HFpEF patients. Multicollinearity was examined in all regression models using the Variance Inflation Factor and correlation between variables included in the models. We used 200-fold bootstrapping of the multivariable-adjusted linear regression models to provide bootstrapped CIs.

A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed using Stata v.12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

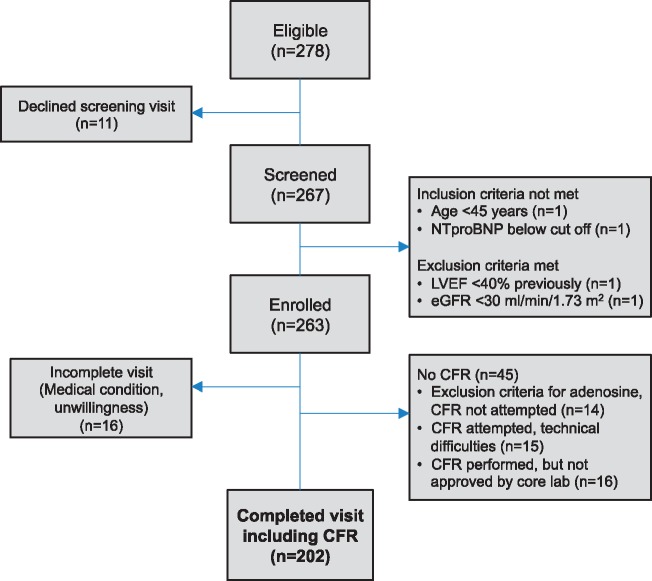

As shown in Figure 1 (patient flow diagram), a total of 263 patients were enrolled at the five study sites. Of these, CFR testing was attempted in 233, of whom 202 (87%) underwent successful CFR testing. As shown in Supplementary material online, Table S1, there were few significant differences between those who did vs. did not undergo successful CFR testing. Those who did not undergo successful CFR testing were more likely African American, less likely Asian, less likely taking a loop diuretic, had higher heart rate and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP), and had a lower 6MWT distance.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram.

The 202 HFpEF patients studied were distributed across the five study sites [n = 56 (28%) from Stockholm, Sweden; n = 51 (25%) from Chicago, USA; n = 40 (20%) from Turku, Finland; n = 35 (17%) from Sahlgrenska, Sweden; and n = 20 (10%) from Singapore]. Of the 202 study participants who underwent successful CFR testing, we found that 151 (74.8%; 95% CI 68.7–80.8%) had evidence of CMD (defined as CFR <2.5). Supplementary material online, Figure S1 displays the cumulative distribution of the CFR values across the PROMIS study participants. The mean ± standard deviation CFR in the study cohort overall was 2.13 ± 0.51, median 2.08 (25th–75th percentile 1.78–2.50).

Clinical (Table 1) and echocardiographic (Table 2) characteristics are presented stratified by presence or absence of CMD. Overall, the enrolled participants had multiple indicators supportive of the diagnosis of HFpEF—they were elderly (mean age 74 years), 55% female, and had multiple comorbidities. Mean KCCQ score (66 ± 22) and 6MWT distance (328 ± 118 meters) were both consistent with prior HFpEF studies and indicated a poor quality of life and reduced exercise tolerance, respectively. NTproBNP values were elevated [median 953 (25th–75th percentile 349–1765) pg/mL], LV EF was preserved (59 ± 8%), 162/202 (80%) had evidence of LV hypertrophy or concentric remodelling, and LV diastolic dysfunction was present in the majority [increased LA volume, reduced tissue Doppler e′ velocities, and elevated E/e′ ratio (Table 2)]. The mean HFA-PEFF score was 6.1 ± 1.6, and the majority [165/202 (82%)] had a score of ≥5, indicative of definite HFpEF based on resting echocardiographic and NTproBNP data obtained as part of the present study. The majority of those with an HFA-PEFF score <5 had a prior history of elevated LV filling pressures on invasive haemodynamic testing [22/37 (59%)], and the rest had a prior history of HF hospitalization, increased natriuretic peptides, and/or increased E/e’ ratio.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the PROMIS-HFpEF study participants, stratified by presence or absence of coronary microvascular dysfunction (coronary flow reserve <2.5)

| Clinical characteristics | CMD absent (CFR 2.8 ± 0.3, range 2.5–3.8; N = 51) | CMD present (CFR 1.9 ± 0.3, range 1.1–2.4; N = 151) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72.4 ± 9.0 | 74.7 ± 8.7 | 0.11 |

| Female, n (%) | 32 (63) | 79 (52) | 0.20 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.023 | ||

| White | 42 (82) | 132 (87) | |

| African American | 5 (10) | 2 (1) | |

| Asian | 4 (8) | 17 (11) | |

| NYHA class, n (%)a | 0.19 | ||

| I | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| II | 34 (67) | 115 (76) | |

| III | 15 (29) | 34 (23) | |

| IV | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 47 (92) | 123 (81) | 0.07 |

| Coronary artery diseaseb | 8 (16) | 31 (21) | 0.45 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 18 (35) | 88 (58) | 0.004 |

| Diabetes | 13 (25) | 45 (30) | 0.56 |

| Obesity | 22 (43) | 49 (32) | 0.17 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 26 (51) | 85 (56) | 0.51 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 25 (49) | 80 (53) | 0.63 |

| Cigarette smokerc | 22 (43) | 106 (70) | <0.001 |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| ACE-inhibitor or ARB | 33 (65) | 116 (77) | 0.09 |

| β-blocker | 33 (65) | 116 (77) | 0.09 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 20 (39) | 50 (33) | 0.43 |

| Loop diuretic | 33 (65) | 87 (58) | 0.37 |

| Thiazide diuretic | 8 (16) | 14 (9) | 0.20 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 17 (33) | 35 (23) | 0.15 |

| Statin | 27 (53) | 89 (59) | 0.45 |

| Aspirin | 18 (35) | 38 (25) | 0.16 |

| Anticoagulant | 17 (33) | 84 (56) | 0.006 |

| Vital signs, physical characteristics, and laboratory data | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 139.1 ± 20.4 | 139.6 ± 22.2 | 0.89 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 74.7 ± 11.5 | 76.5 ± 12.6 | 0.37 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 66.5 ± 9.2 | 70.9 ± 13.9 | 0.035 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 32.5 ± 10.7 | 29.0 ± 8.5 | 0.017 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.8 ± 1.3 | 13.0 ± 1.5 | 0.52 |

| Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratiod (mg/g) | 2.4 (1.1–3.7) | 4.3 (1.4–18.8) | 0.036 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 63 ± 20 | 59 ± 19 | 0.16 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 6.2 ± 1.9 | 6.5 ± 2.3 | 0.34 |

| Haemoglobin A1c (%) | 42.9 ± 9.6 | 45.2 ± 11.9 | 0.23 |

| NTproBNPc (pg/mL) | 597 (190–1410) | 1050 (396–1930) | 0.004 |

| Troponin Tc (ng/mL) | 10.0 (10.0–16.4) | 14.0 (10.0–25.6) | 0.002 |

| High-sensitivity CRPc (mg/dL) | 2.3 (0.9–5.5) | 2.3 (1.0–5.0) | 0.76 |

Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages; continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise specified.

NYHA Class I on the day of enrolment into the study.

Previously revascularized coronary artery disease (e.g. coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous coronary intervention).

Current or prior smoking history.

Median (25th–75th percentile).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic characteristics of the PROMIS-HFpEF study participants, stratified by presence or absence of coronary microvascular dysfunction (coronary flow reserve <2.5)

| Echocardiographic parameters | CMD absent (CFR 2.8 ± 0.3, range 2.5–3.8; N = 51) | CMD present (CFR 1.9 ± 0.3, range 1.1–2.4; N = 151) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left heart structure/function | |||

| Septal wall thickness (cm) | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.61 |

| Posterior wall thickness (cm) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.31 |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.46 ± 0.10 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.47 |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 102.1 ± 26.1 | 110.3 ± 36.6 | 0.14 |

| LV end-diastolic volume index (mL/m2) | 44.8 ± 12.2 | 42.3 ± 12.1 | 0.21 |

| LV end-systolic volume index (mL/m2) | 17.7 ± 6.1 | 18.0 ± 8.1 | 0.79 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 60.9 ± 6.4 | 58.5 ± 8.1 | 0.06 |

| LV ejection fraction >50%, n (%) | 48 (94) | 131 (87) | 0.15 |

| LA volume index (mL/m2) | 36.5 ± 11.0 | 39.3 ± 13.4 | 0.18 |

| E velocity (cm/s) | 90.7 ± 27.6 | 99.8 ± 28.1 | 0.045 |

| A velocity (cm/s) | 87.4 ± 31.8 | 80.1 ± 34.2 | 0.25 |

| E/A ratio | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.12 |

| Right heart structure/function | |||

| RV wall thickness (cm) | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 0.016 |

| RV end-diastolic area (cm2) | 18.9 ± 4.7 | 19.0 ± 5.2 | 0.90 |

| RV end-systolic area (cm2) | 10.8 ± 3.1 | 11.2 ± 0.3 | 0.55 |

| RV fractional area change (%) | 43.3 ± 6.5 | 42.0 ± 8.2 | 0.32 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 19.7 ± 3.6 | 17.5 ± 3.7 | <0.001 |

| Right atrial area (cm2) | 19.0 ± 5.6 | 20.8 ± 6.9 | 0.10 |

| Tissue Doppler indicesa | |||

| LV s′ velocity (cm/s) | 7.3 ± 2.1 | 6.3 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| LV e′ velocity (cm/s) | 8.1 ± 2.4 | 8.9 ± 5.9 | 0.36 |

| LV a′ velocity (cm/s) | 8.6 ± 2.8 | 7.5 ± 3.1 | 0.06 |

| LV E/e′ ratio | 12.4 ± 4.7 | 13.5 ± 6.2 | 0.24 |

| RV s′ velocity (cm/s) | 12.7 ± 3.1 | 11.3 ± 3.1 | 0.005 |

| RV e′ velocity (cm/s) | 13.1 ± 4.6 | 13.3 ± 5.0 | 0.80 |

| RV a′ velocity (cm/s) | 15.3 ± 5.9 | 14.2 ± 6.2 | 0.34 |

| RV E/e′ ratio | 4.5 ± 2.2 | 4.8 ± 2.6 | 0.43 |

| Haemodynamics | |||

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 6.8 ± 2.8 | 7.0 ± 3.2 | 0.66 |

| PA systolic pressure (mmHg) | 40.5 ± 10.8 | 45.6 ± 15.3 | 0.05 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 18.3 ± 2.5 | 18.6 ± 3.3 | 0.51 |

| Stroke volume (mL) | 83 ± 29 | 71 ± 22 | 0.001 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 5.1 ± 1.6 | 4.7 ± 1.4 | 0.07 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (WU) | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 0.014 |

| Pressure-volume analysis | |||

| Systemic arterial elastance (mmHg/mL) | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 0.01 |

| LV end-systolic elastance (mmHg/mL) | 7.6 ± 4.3 | 9.4 ± 5.6 | 0.041 |

| Systemic SV/PP ratio (mL/mmHg) | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.003 |

| TAPSE/PASP ratio (cm/mmHg) | 0.52 ± 0.14 | 0.43 ± 0.18 | 0.006 |

| Speckle-tracking echocardiography (%)b | |||

| LV global longitudinal strain | 17.0 ± 3.5 | 15.7 ± 3.5 | 0.023 |

| RV free wall strain | 23.3 ± 5.1 | 21.6 ± 5.2 | 0.05 |

| LA reservoir strain | 19.8 ± 8.3 | 15.0 ± 7.7 | <0.001 |

All LV tissue Doppler values represent average of septal and lateral indices.

All speckle-tracking measures are presented as absolute values.

Patients with CMD were more likely to have a history of atrial fibrillation (and taking anticoagulants) and were more often current or former smokers (Table 1). Participants in the CMD group had slightly lower BMI and higher heart rates, but other vital signs and physical characteristics were similar between groups. On laboratory testing, UACR, troponin, and NTproBNP were all higher in the CMD group compared to the non-CMD group. High-sensitivity CRP, a marker of systemic inflammation, was not associated with either CMD or CFR (P = 0.95).

Conventional echocardiography (resting 2D, Doppler, and tissue Doppler) parameters were similar between groups except for lower stroke volume, reduced longitudinal systolic function (s′ velocity) of the left ventricle and right ventricle, greater right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy, and higher estimated pulmonary vascular resistance in participants with CMD (Table 2). Non-invasive pressure–volume analysis revealed stiffer left ventricle and aorta, and evidence of worse RV-pulmonary artery coupling (lower ratio of tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) to estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure) in the CMD group. On speckle-tracking analysis, longitudinal systolic strain of the left ventricle, left atrium, and right ventricle were all lower (worse) in the CMD group compared with the non-CMD group (Table 2).

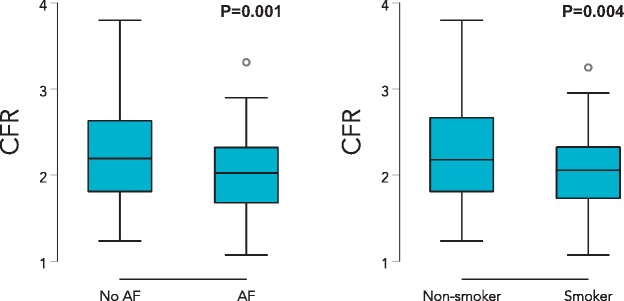

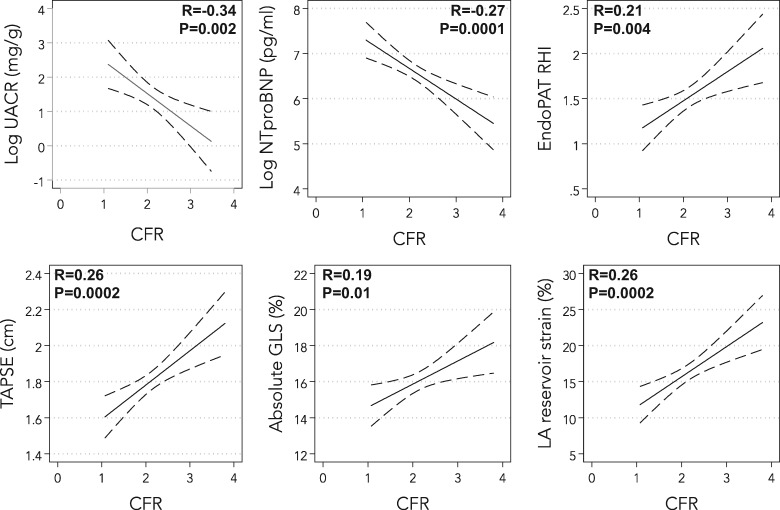

When examined as a continuous variable, participants with a history of current or former smoking, and those with a history of atrial fibrillation, had lower CFR values (Figure 2). In a multivariable model including age, sex, BMI, diabetes mellitus, history of revascularized CAD, smoking, and atrial fibrillation, both smoking [beta-coefficient −0.20 (95% CI −0.34 to −0.05), P = 0.007] and atrial fibrillation [beta-coefficient −0.17 (95% CI −0.31 to −0.03), P = 0.02] were still associated with lower values of CFR. Lower CFR was also associated with higher UACR and NTproBNP, and lower reactive hyperaemia index (RHI), TAPSE, LV global longitudinal strain, and LA reservoir strain on univariate analysis (Figure 3 andSupplementary material online, Table S2). Coronary flow reserve was not associated with either KCCQ score or 6MWT. Worse CFR was still associated with higher UACR and NTproBNP, and lower RHI, TAPSE, and RV free wall strain after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, revascularized CAD, smoking, left ventricular mass, and study site (P < 0.05 for all models) (Table 3). Tests for multicollinearity showed that atrial fibrillation and LA reservoir strain were highly correlated (r = −0.75); indeed, CFR remained associated with LA reservoir strain after multivariable adjustment when atrial fibrillation was excluded from the multivariable model. Bootstrapping results were similar to the primary results overall (Supplementary material online, Table S3). Formal interaction testing by age, sex, site, BMI, and atrial fibrillation revealed no statistically significant interactions except for the interaction by BMI on the association between CFR and RHI (BMI × CFR interaction term P = 0.03). There was a stronger association between CFR and RHI in those with obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2; r = 0.40, P = 0.01) compared with those without obesity (BMI ≤30 kg/m2; r = 0.16, P = 0.09).

Figure 2.

Box-and-whisker plots showing coronary flow reserve stratified by presence or absence of atrial fibrillation (left panel) and current or prior smoking (right panel). AF, atrial fibrillation.

Figure 3.

Correlations between coronary flow reserve and biomarkers, systemic endothelial function, and echocardiographic parameters. CFR, coronary flow reserve; GLS, left ventricular global longitudinal strain; LA, left atrial; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; RHI, reactive hyperaemia index, a marker of systemic endothelial function; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; UACR, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Table 3.

Association between coronary flow reserve and biomarkers, quality of life, 6 min walk test distance, systemic endothelial function, and echocardiographic parameters on linear regression analysis

| Parameters | Unadjusted |

Multivariable adjusteda |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-coefficient (95% CI)b | P-value | β-coefficient (95% CI)b | P-value | |

| Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (mg/g) | 5.0 (3.3–9.0) | 0.003 | 4.1 (2.7–6.7) | 0.028 |

| NTproBNP (pg/mL) | 606 (231–981) | 0.002 | 543 (132–954) | 0.010 |

| KCCQ summary score | −0.3 (−3.3 to 2.8) | 0.87 | — | — |

| 6MWT distance (m) | −7 (−24 to 10) | 0.39 | — | — |

| Reactive hyperaemia index | −0.17 (−0.28 to −0.05) | 0.004 | −0.11 (−0.21 to 0.00) | 0.041 |

| LV s′ velocity (cm/s) | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.2) | 0.002 | −0.03 (−0.25 to 0.20) | 0.80 |

| LV global longitudinal strain (%) | −0.7 (−1.2 to −0.2) | 0.010 | −0.06 (−0.50 to 0.38) | 0.79 |

| Stroke volume (mL) | −4.3 (−7.6 to −0.9) | 0.012 | −0.5 (−3.6 to 2.6) | 0.75 |

| TAPSE (mm) | −0.98 (−1.48 to −0.46) | <0.001 | −0.52 (−1.03 to −0.02) | 0.042 |

| RV s′ velocity (cm/s) | −0.4 (−0.9 to 0.02) | 0.059 | — | — |

| RV free wall strain (%) | −1.0 (−1.7 to −0.3) | 0.005 | −0.8 (−1.5 to −0.1) | 0.022 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (WU) | 0.20 (0.09–0.32) | 0.001 | 0.09 (−0.03 to 0.21) | 0.15 |

| LA reservoir strain (%) | −2.1 (−3.2 to −1.0) | <0.001 | −0.50 (−1.30 to 0.30) | 0.22 |

Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, coronary artery disease, smoking, LV mass, and study site.

Per 1-standard deviation decrease in coronary flow reserve.

Discussion

In PROMIS, the largest prospective, multi-centre study of CFR in HFpEF, we found that the prevalence of CMD was high (75%). The comorbidities most closely associated with CMD were a history of smoking and atrial fibrillation. In addition, we found that HFpEF patients with CMD had higher UACR and lower RHI, markers of systemic endothelial dysfunction, even after adjustment for potential confounders. Furthermore, we found that CFR was still associated with markers of HF severity (NTproBNP and RV dysfunction) after multivariable adjustment. These data support preclinical findings that suggest that HFpEF is a systemic disorder associated with endothelial dysfunction and microvascular disease in the heart and other organs.

As shown in Table 4, while other studies of CMD and HFpEF have been published,4,16–20 these prior studies are either small (n = 30 or less with HFpEF) or are retrospective and based on convenience samples of patients who underwent nuclear imaging for other reasons (e.g. evaluation of CAD). PROMIS builds on these important prior studies by demonstrating the high prevalence of impaired CFR in a prospective, multi-centre, and multinational study with rigorously defined HFpEF. Furthermore, PROMIS is the first study to demonstrate an association between reduced CFR and peripheral (systemic) endothelial dysfunction (as measured by the EndoPAT) in HFpEF patients. Furthermore, using systematic and comprehensive echocardiography, we found that reduced CFR is associated with multiple indices of abnormal longitudinal (subendocardial) myocardial dysfunction.

Table 4.

Comparison of the PROMIS-HFpEF study to other published studies of coronary microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

| First author (year) | Sample size | Study design | Method | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah (2018) PROMIS-HFpEF | n = 202 HFpEF | Prospective, multi-centre, multi-national | Echo/Doppler CFR (CMD = CFR< 2.5) | CMD prevalence in HFpEF = 75%. CMD patients were more likely to have a history of atrial fibrillation and smoking. CFR correlated with multiple indices including UACR, NTproBNP, RHI, TAPSE, RV, LV, and LA strain |

| Dryer (2018) | n = 30 HFpEF, n = 14 controls | Prospective, two centre | Invasive coronary Doppler (CFR and IMR); CMD = CFR ≤2.0 + IMR ≥23) | CMD prevalence in HFpEF = 37% using CFR ≤2.0 + IMR ≥23; CMD prevalence in HFpEF = 47% using CFR <2.0; four-quadrant approach to defining CMD based on CFR and IMR |

| Taqueti (2017) | n = 201 without HFpEF (n = 36 with subsequent incident HFpEF) | Retrospective, single centre | Rb-82 PET (CMD = CFR <2.0) | CMD was an independent risk factor for incident HFpEF; lower CFR was associated with worse LV diastolic function |

| Srivaratharajah (2016) | n = 78 HFpEF, n = 298 non-HFpEF | Retrospective, single centre | Rb-82 PET (CMD = MFR<2.0) | CMD prevalence in HFpEF = 40%; patients with HFpEF 2.6 times more likely to have CMD than controls even after adjustment for comorbidities |

| Kato (2016) | n = 25 HFpEF, n = 13 hypertensive LVH, and n = 18 controls | Prospective, single centre | Cardiac MRI (CMD = CFR<2.5) | CMD prevalence in HFpEF = 76%; CFR was lower in HFpEF compared with hypertensive LVH and controls; CFR correlated with BNP levels |

| Sucato (2015) | n = 155 HFpEF, n = 131 non-HFpEF | Retrospective, single centre | Invasive coronary angiography (TIMI frame count and TIMI myocardial perfusion grade) | HFpEF patients had worse TIMI frame count and worse TIMI myocardial perfusion grade in all three major coronary artery territories compared to controls |

| Mohammed (2015) | n = 124 HFpEF, n = 104 controls | Retrospective, single centre | Autopsy/pathology | Compared to controls, HFpEF patients had more coronary microvascular rarefaction and myocardial fibrosis. Microvascular density was inversely associated with myocardial fibrosis |

Doppler echocardiography for assessment of CFR has been validated and is reproducible, comparable to positron emission tomography (PET)-based CFR, and has been endorsed by the European Society of Cardiology.29–31 Compared with other methods Doppler echocardiography-based CFR assessment is relatively inexpensive, non-invasive, nearly universally applicable, and does not require radiation. Impaired CFR, whether measured by Doppler echocardiography, PET imaging, or invasive coronary evaluation, is a marker of CMD and is known to reflect endothelial dysfunction (though it can also be influenced by non-endothelial factors, capillary rarefaction, myocardial fibrosis, and elevated LV filling pressures).32 While fractional flow reserve reflects severity of focal coronary artery lesions, CFR is a measure of the global coronary vascular function. Reduced CFR has been shown to confer prognostic information for cardiovascular outcome in various conditions.32

Reduced CFR is also present in patients with systemic inflammation and improves after immunomodulatory treatment, and is reduced in comorbidities associated with and potentially driving HFpEF, such as diabetes and hypertension. In the present study, we did not find an association between reduced CFR and these factors, possibly because of the high prevalence of these comorbidities in patients with established HFpEF, or because reduced CFR was due to resultant myocardial fibrosis (with extrinsic compression of the coronary microvessels) and coronary microvascular rarefaction rather than the comorbidities themselves. The association of reduced CFR and elevated NTproBNP supports this hypothesis as the latter is a measure of HF severity and may be reflective of significant myocardial disease (e.g. myocardial fibrosis and capillary rarefaction). We did find an association between smoking and reduced CFR in HFpEF, which is consistent with prior studies that have found that smokers have endothelial dysfunction and CMD.33,34 Our finding that atrial fibrillation is strongly associated with impaired CFR is consistent with other studies in the absence of HFpEF; factors mediating this association may include the arrhythmia itself, sympathetic innervation, neurohormonal activation, endothelial dysfunction, or myocardial remodelling, all factors that could be present in both HFpEF and atrial fibrillation.35

In our study, we also did not find an association between impaired CFR and quality of life (as measured by the KCCQ) or 6MWT distance. Reasons for the lack of association are unclear, but one possibility is that in elderly HFpEF patients, qualify of life and reduced exercise tolerance are multifactorial, and are likely due to both CMD and other cardiac and non-cardiac factors.

Several studies have previously found that systemic endothelial dysfunction, quantitated by EndoPAT RHI, is abnormal in HFpEF and, when reduced, is associated with a worse prognosis.12,36,37 Our results add to these prior studies by demonstrating an independent association between reduced CFR and reduced RHI. Given these findings, for future clinical trials targeting CMD in HFpEF, assessment of RHI is an attractive method to identify patients who are most likely to have CMD without having to perform detailed coronary flow assessments. This may be especially important for large-scale pivotal studies, where CFR assessment may not be feasible. Alternatively, if HFpEF is defined according to the rigorous but universally available criteria used here, investigators may assume that a majority of, but not all, patients will have reduced CFR.

We found that of all echocardiographic parameters, impaired CFR was most associated with longitudinal fibre systolic (contractile) abnormalities in multiple cardiac chambers (left ventricle, left atrium, and right ventricle). Longitudinal systolic function is reflective of the health of the subendocardium; thus, it is not surprising that CMD is most associated with these abnormalities given the fact that the subendocardium is most affected by CMD. Indeed, we have previously found that increased UACR, a marker of systemic endothelial dysfunction, is associated with LV longitudinal strain in individuals at risk for HFpEF38 and in overt HFpEF.39 We also found an association between reduced CFR and worse LA strain, which is associated with worse outcomes, higher pulmonary vascular resistance, and reduced peak VO2 on cardiopulmonary exercise testing in HFpEF.8

Approximately 25% of the HFpEF patients enrolled in our study did not have evidence of CMD. There are several potential explanations for this finding. First, HFpEF is a heterogeneous syndrome; it is possible that these patients have a more ‘extra-cardiac’ cause of fluid overload instead of a myocardial-specific phenotype. The lesser degree of impairment in longitudinal systolic strain of the left ventricle, left atrium, and right ventricle in these patients supports this hypothesis. Second, given similarities in diastolic dysfunction between the two groups, it may be that other factors besides endothelial dysfunction are the cause of the HFpEF syndrome in these patients.

Strengths and limitations

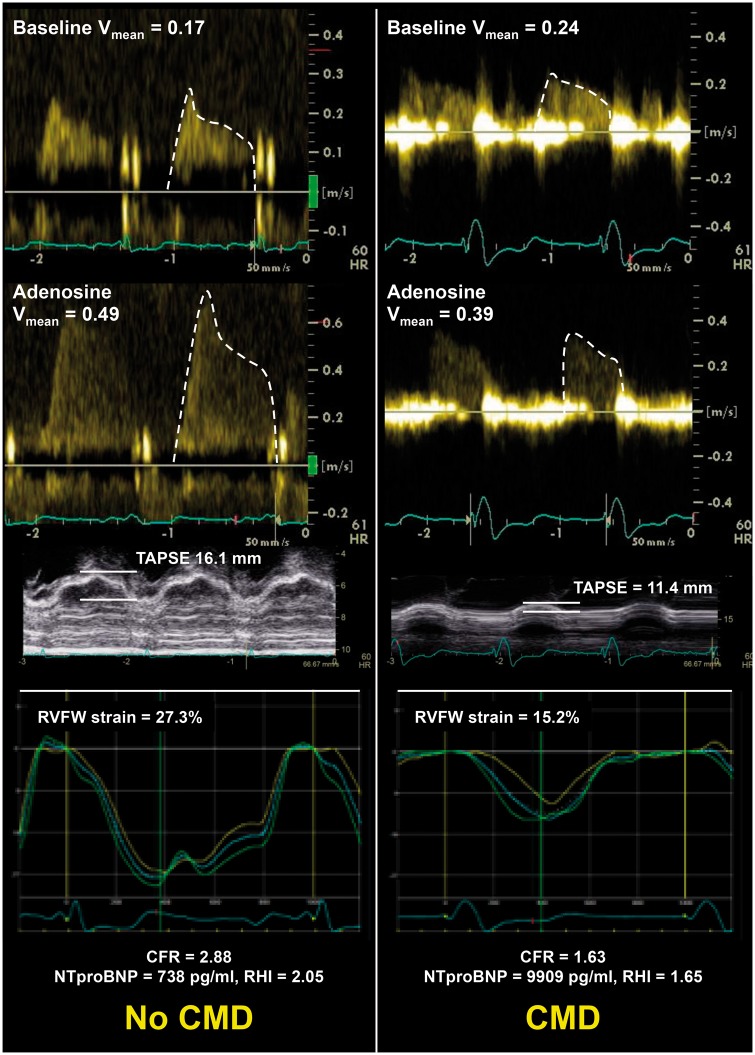

Our study has several strengths. First, the multi-centre, multinational, prospective evaluation of a large number of HFpEF patients increases the generalizability of our findings. Second, we successfully enrolled patients who met criteria for definite HFpEF, as indicated by the high HFA-PEFF score, and the fact that all patients met contemporary criteria for the HFpEF diagnosis. Third, we performed multimodality assessment of patients, which provided novel insight into type of HFpEF patients who have CMD, as summarized in the data from two example patients from our study shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Examples of coronary Doppler tracings at rest and with adenosine, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, and right ventricular free wall strain curves in a study patient without coronary microvascular dysfunction (left panel) vs. a study patient with coronary microvascular dysfunction (right panel). The patient without coronary microvascular dysfunction had a normal coronary flow reserve (2.88), whereas the patient with coronary microvascular dysfunction had a reduced coronary flow reserve (1.63). The lower coronary flow reserve in the patient with coronary microvascular dysfunction was associated with lower tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion and worse right ventricular free wall strain (as shown in the figure), as well as lower reactive hyperaemia index (1.65 vs. 2.05), worse left ventricular global longitudinal strain (7.8% vs. 13.2%), and worse left atrial reservoir strain (6.7% vs. 15.8%). CFR, coronary flow reserve; CMD, coronary microvascular dysfunction; LV, left ventricular; RHI, reactive hyperaemia index; RV, right ventricular; RVFW, right ventricular free wall; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Our study is limited by lack of longitudinal outcomes and comorbidity-matched controls, such data could have enhanced our study by allowing us to determine the prognostic utility of CMD, and would have allowed us to definitively prove that CMD is much higher in HFpEF than in those who have multiple cardiac risk factors but no HFpEF. However, several prior studies have examined the presence of CMD in non-HFpEF populations, and we found that the prevalence of CMD is much higher in HFpEF compared with the prevalence of CMD in the setting of stable CAD, diabetes, and hypertension. In addition, even though each site strictly followed guideline-recommended investigation of CAD when suspected, we did not collect detailed data on how many patients underwent coronary angiography, coronary computed tomography, or stress testing. We are also unable to exclude diffuse coronary artery atherosclerosis as potential reason for impaired CFR in the HFpEF patients. Systematic coronary angiography in all patients to exclude macrovascular CAD and invasive coronary assessment of the index of microvascular resistance would have been difficult in a study the size of PROMIS, but both could have added an additional dimension to the evaluation of CMD in HFpEF.18 However, our finding that peripheral endothelial dysfunction (i.e. RHI) correlates with Doppler CFR argues that irrespective of macrovascular CAD, there is a widespread endothelial/microvascular dysfunction present in the majority of patients with HFpEF.

Conclusions

Impaired coronary microvascular function is highly prevalent in HFpEF patients and is associated with NTproBNP (a marker of HF severity), systemic endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac dysfunction (Take home figure). Microvascular dysfunction may be a promising composite risk marker and therapeutic target in HFpEF.

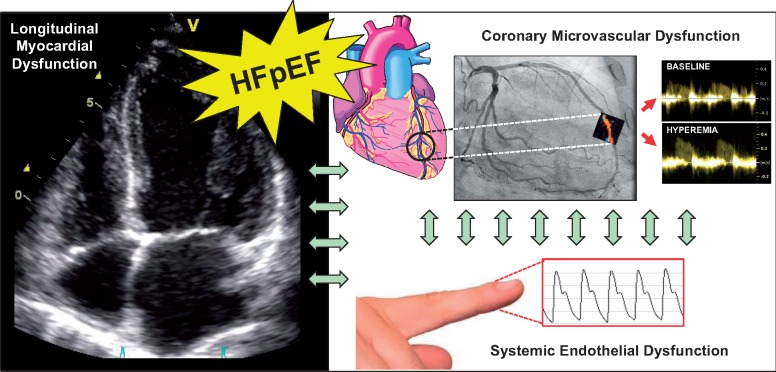

Take home figure.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction—systemic endothelial dysfunction, coronary microvascular dysfunction, and longitudinal myocardial dysfunction. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is associated with a high prevalence of longitudinal fibre (subendocardial) myocardial dysfunction, coronary microvascular dysfunction, and systemic endothelial dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the following study staff for their work on the PROMIS-HFpEF study: Ann Lindström, Ashwin Venkatesh, Ann Hultman-Cadring, Neal Pohlman, Juliet Ryan, Miriam Kåveryd Holmström, and Sofie Andréen.

Funding

S.J.S. is supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health grants [R01 HL105755 and R01 HL127028] and American Heart Association grants [#16SFRN28780016 and #15CVGPSD27260148]. C.S.L. is supported by a Clinician Scientist Award from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore.

Conflict of interest: S.J.S. has received research grants from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Corvia, and Novartis; and consulting fees from Actelion, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cardiora, Eisai, Ironwood, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, Tenax, and United Therapeutics. C.S.L. has received research support from Boston Scientific, Bayer, Roche Diagnostics, Medtronic, and Vifor Pharma; and has consulted for Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Novartis, Amgen, Merck, Janssen Research & Development LLC, Menarini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Abbott Diagnostics, Corvia, Stealth BioTherapeutics, and Takeda. A.S. received research grants from Academy of Finland and Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research during the conduct of the study; and consulting fees from GE healthcare, Novartis, Abbot, Astra Zeneca. C.H. has received consulting fees from Novartis and MSD. M.L.F., M.A.B., and L.M.G. are all employees of AstraZeneca R&D. All other authors have no disclosures. L.H.L. has received research grants from Novartis, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Vifor Pharma, and AstraZeneca, and consulting fees from Novartis, Merck, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Sanofi, Vifor Pharma, and AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

See page 3451 for the editorial comment on this article (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy558)

References

- 1. Franssen C, Chen S, Unger A, Korkmaz HI, De Keulenaer GW, Tschope C, Leite-Moreira AF, Musters R, Niessen HW, Linke WA, Paulus WJ, Hamdani N.. Myocardial microvascular inflammatory endothelial activation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:312–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lam CS, Brutsaert DL.. Endothelial dysfunction: a pathophysiologic factor in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1787–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lam CS, Lund LH.. Microvascular endothelial dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart 2016;102:257–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mohammed SF, Hussain S, Mirzoyev SA, Edwards WD, Maleszewski JJ, Redfield MM.. Coronary microvascular rarefaction and myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 2015;131:550–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paulus WJ, Tschope C.. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P.. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2016;69:1167.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Redfield MM. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1868–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Freed BH, Daruwalla V, Cheng JY, Aguilar FG, Beussink L, Choi A, Klein DA, Dixon D, Baldridge A, Rasmussen TLJ, Maganti K, Shah SJ.. Prognostic utility and clinical significance of cardiac mechanics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: importance of left atrial strain. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:pii: e003754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kraigher-Krainer E, Shah AM, Gupta DK, Santos A, Claggett B, Pieske B, Zile MR, Voors AA, Lefkowitz MP, Packer M, McMurray JJ, Solomon SD, Investigators P.. Impaired systolic function by strain imaging in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:447–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burkhoff D, Maurer MS, Joseph SM, Rogers JG, Birati EY, Rame JE, Shah SJ.. Left atrial decompression pump for severe heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: theoretical and clinical considerations. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Borlaug BA, Jaber WA, Ommen SR, Lam CS, Redfield MM, Nishimura RA.. Diastolic relaxation and compliance reserve during dynamic exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart 2011;97:964–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CS, Flood KS, Lerman A, Johnson BD, Redfield MM.. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:845–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee JF, Barrett-O'Keefe Z, Garten RS, Nelson AD, Ryan JJ, Nativi JN, Richardson RS, Wray DW.. Evidence of microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart 2016;102:278–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marechaux S, Samson R, van Belle E, Breyne J, de Monte J, Dedrie C, Chebai N, Menet A, Banfi C, Bouabdallaoui N, Le Jemtel TH, Ennezat PV.. Vascular and microvascular endothelial function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Card Fail 2016;22:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Narang N, Medvedofsky D, Dryer K, Shah SJ, Davidson CJ, Patel AR, Blair JEA.. Microvascular dysfunction and cardiac fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a case report. ESC Heart Fail 2017;4:645–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sucato V, Evola S, Novo G, Sansone A, Quagliana A, Andolina G, Assennato P, Novo S.. Angiographic evaluation of coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Microcirculation 2015;22:528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Taqueti VR, Solomon SD, Shah AM, Desai AS, Groarke JD, Osborne MT, Hainer J, Bibbo CF, Dorbala S, Blankstein R, Di Carli MF.. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and future risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 2018;39:840–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dryer K, Gajjar M, Narang N, Lee M, Paul J, Shah AP, Nathan S, Butler J, Davidson CJ, Fearon WF, Shah SJ, Blair JEA.. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018;314:H1033–H1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kato S, Saito N, Kirigaya H, Gyotoku D, Iinuma N, Kusakawa Y, Iguchi K, Nakachi T, Fukui K, Futaki M, Iwasawa T, Kimura K, Umemura S.. Impairment of coronary flow reserve evaluated by phase contrast cine-magnetic resonance imaging in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e002649.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Srivaratharajah K, Coutinho T, deKemp R, Liu P, Haddad H, Stadnick E, Davies RA, Chih S, Dwivedi G, Guo A, Wells GA, Bernick J, Beanlands R, Mielniczuk LM.. Reduced myocardial flow in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9:e002562.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joseph SM, Novak E, Arnold SV, Jones PG, Khattak H, Platts AE, Davila-Roman VG, Mann DL, Spertus JA.. Comparable performance of the Kansas City cardiomyopathy questionnaire in patients with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:1139–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ.. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:1440–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB.. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:685–713; quiz 786–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF 3rd, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, Flachskampf FA, Gillebert TC, Klein AL, Lancellotti P, Marino P, Oh JK, Popescu BA, Waggoner AD.. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:277–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, Marino PN, Oh JK, Smiseth OA, Waggoner AD, Flachskampf FA, Pellikka PA, Evangelista A.. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2009;22:107–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, Lancellotti P, Muraru D, Picard MH, Rietzschel ER, Rudski L, Spencer KT, Tsang W, Voigt JU.. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1–39.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burke MA, Katz DH, Beussink L, Selvaraj S, Gupta DK, Fox J, Chakrabarti S, Sauer AJ, Rich JD, Freed BH, Shah SJ.. Prognostic importance of pathophysiologic markers in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:288–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wittfeldt A, Emanuelsson H, Brandrup-Wognsen G, van Giezen JJ, Jonasson J, Nylander S, Gan LM.. Ticagrelor enhances adenosine-induced coronary vasodilatory responses in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:723–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gan LM, Svedlund S, Wittfeldt A, Eklund C, Gao S, Matejka G, Jeppsson A, Albertsson P, Omerovic E, Lerman A.. Incremental value of transthoracic Doppler echocardiography-assessed coronary flow reserve in patients with suspected myocardial ischemia undergoing myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e004875.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Olsen RH, Pedersen LR, Snoer M, Christensen TE, Ghotbi AA, Hasbak P, Kjaer A, Haugaard SB, Prescott E.. Coronary flow velocity reserve by echocardiography: feasibility, reproducibility and agreement with PET in overweight and obese patients with stable and revascularized coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2015;14:22.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Task Force Members Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, Ferreira JR, Gersh BJ, Gitt AK, Hulot JS, Marx N, Opie LH, Pfisterer M, Prescott E, Ruschitzka F, Sabate M, Senior R, Taggart DP, van der Wall EE, Vrints CJ ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Document R, Knuuti J, Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Claeys MJ, Donner-Banzhoff N, Erol C, Frank H, Funck-Brentano C, Gaemperli O, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Hamilos M, Hasdai D, Husted S, James SK, Kervinen K, Kolh P, Kristensen SD, Lancellotti P, Maggioni AP, Piepoli MF, Pries AR, Romeo F, Ryden L, Simoons ML, Sirnes PA, Steg PG, Timmis A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Yildirir A, Zamorano JL.. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gan LM, Wikstrom J, Fritsche-Danielson R.. Coronary flow reserve from mouse to man–from mechanistic understanding to future interventions. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2013;6:715–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gullu H, Caliskan M, Ciftci O, Erdogan D, Topcu S, Yildirim E, Yildirir A, Muderrisoglu H.. Light cigarette smoking impairs coronary microvascular functions as severely as smoking regular cigarettes. Heart 2007;93:1274–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Messner B, Bernhard D.. Smoking and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34:509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Range FT, Schafers M, Acil T, Schafers KP, Kies P, Paul M, Hermann S, Brisse B, Breithardt G, Schober O, Wichter T.. Impaired myocardial perfusion and perfusion reserve associated with increased coronary resistance in persistent idiopathic atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2223–2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Akiyama E, Sugiyama S, Matsuzawa Y, Konishi M, Suzuki H, Nozaki T, Ohba K, Matsubara J, Maeda H, Horibata Y, Sakamoto K, Sugamura K, Yamamuro M, Sumida H, Kaikita K, Iwashita S, Matsui K, Kimura K, Umemura S, Ogawa H.. Incremental prognostic significance of peripheral endothelial dysfunction in patients with heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1778–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matsue Y, Suzuki M, Nagahori W, Ohno M, Matsumura A, Hashimoto Y, Yoshida K, Yoshida M.. Endothelial dysfunction measured by peripheral arterial tonometry predicts prognosis in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Katz DH, Selvaraj S, Aguilar FG, Martinez EE, Beussink L, Kim KY, Peng J, Sha J, Irvin MR, Eckfeldt JH, Turner ST, Freedman BI, Arnett DK, Shah SJ.. Association of low-grade albuminuria with adverse cardiac mechanics: findings from the hypertension genetic epidemiology network (HyperGEN) study. Circulation 2014;129:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Katz DH, Burns JA, Aguilar FG, Beussink L, Shah SJ.. Albuminuria is independently associated with cardiac remodeling, abnormal right and left ventricular function, and worse outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2014;2:586–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.