Abstract

Satellite sensors are powerful tools to monitor the spatiotemporal variations of air pollutants in large scales, but it has been challenging to detect surface O3 due to the presence of abundant stratospheric and upper tropospheric O3. East Asia is one of the most polluted regions in the world, but anthropogenic emissions such as NOx and SO2 began to decrease in 2010s. This trend was well observed by satellites, but the spatiotemporal impacts of these emission trends on O3 have not been well understood. Recent advancement in a retrieval method for the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) sensor enabled detection of lower tropospheric O3 and its legitimacy has been validated. In this study, we investigated the statistical significance for the OMI sensor to detect the lower tropospheric O3 responses to the future emission reduction of the O3 precursor gases over East Asia in summer, by utilizing a regional chemistry model. The emission reduction of 10, 25, 50, and 90% resulted in 4.4, 11, 23, and 53% decrease of the areal and monthly mean daytime simulated satellite-detectable O3 (ΔO3), respectively. The fractions of significant areas are 55, 84, 93, and 96% at a one-sided 95% confidence interval. Because of the recent advancement of satellite sensor technologies (e.g., TROPOMI), study on tropospheric photochemistry will be rapidly advanced in the near future. The current study proved the usefulness of such satellite analyses on the lower tropospheric O3 and its perturbations due to the precursor gas emission controls.

Subject terms: Atmospheric chemistry, Environmental impact

Introduction

Surface O3 causes detrimental effects on plants and animals1. Tropospheric O3 is an important climate forcing agent causing global warming2. Surface and lower tropospheric O3 is mainly produced by photochemical reactions between NOx and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs). The Asian anthropogenic nitrogen oxide emissions surpassed those from North America and Europe in 1990s3 and since then the emissions continued to increase in 2000s4. Cooper et al.5 showed based on the in-situ measurements that the daytime O3 in the summer in China was remarkably larger than that over other locations in the world in 2000s. In 2010s, the Chinese anthropogenic emissions such as NOx and SO2 began to decrease and this trend was well observed by satellites6–9. However, because the reduction of NOx emissions increased photochemical production of O3 near the emission source regions (VOC-limited regions)10, it is not necessary that the lower tropospheric O3 in China and East Asia have started to decrease, associated with the decrease in NOx emission in China, Korea, and Japan. Also the local/regional emission reduction may not decrease local/regional O3 concentrations, because the trans-boundary to hemispheric transport contributes to raise the background level of the surface and the lower tropospheric O3 concentrations11.

In order to monitor the spatiotemporal variations of air pollutants in large scales and to detect their long-term trends, satellite sensors are powerful tools. However, in terms of the surface and lower tropospheric O3, it has been challenging to measure from the space, because of the presence of abundant stratospheric O3. Recently, a retrieval algorithm has been developed by Liu et al.12 to detect the lower-tropospheric (i.e., approximately 0–3 km) O3 and its legitimacy has been validated especially focusing on the East Asian region13–16. In fact, based on the climatological zonal and monthly mean O3 profiles derived from 15 years of ozonesonde measurements17, the 0–3 km column amounts in the northern mid-latitudes range from 7.1 to 13.7 DU, which are only 2.1–4.0% of the total column amounts, approximately 300–380 DU. In this study, we investigated the statistical significance for the OMI sensor to detect the tropospheric O3 responses to the current/future emission reductions of the O3 precursor gases (NOx and NMVOCs) over East Asia by using the retrieval algorithm and numerical simulations. We selected June 2006 in the study, because both observed and simulated lower tropospheric O3 concentrations were largest. Also, the summer was most favorable for the current analysis, evaluating sensitivity of O3 to local precursor emission changes. In colder seasons, the contribution of long-range transport is larger due to monsoon and lower photochemical production. More than half of surface O3 in East Asia were attributed to those transported from distant sources, whereas most of them were the domestic origin in the summer11. In addition, the retrieval sensitivity to lower tropospheric O3 in this region maximizes in the summer due to smaller solar zenith angle12.

Results and Discussion

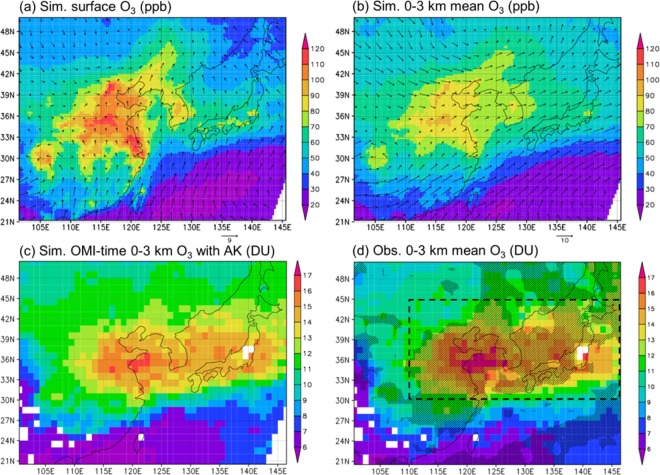

Spatial distribution of lower tropospheric O3

Figure 1 shows the monthly mean simulated and observed O3 over East Asia in June 2006. The simulation was conducted by using a regional meteorology – chemistry model (NHM-Chem)18. The panels are to show how the simulation results were compared with the retrieved OMI O312,19–21 (denoted as OMI-O3 hereinafter) and how the horizontal distributions were changed accordingly by the averaging procedures. Figure 1a shows the simulated surface O3 concentration (ppb; Δx = 30 km), the most important factor for the terrestrial ecosystems, and thus to be evaluated by the observation. In the summer, the atmospheric conditions are most favorable for the photochemical production of O3 over the land. Because the surface wind was relatively weaker compared to the cold seasons, the surface concentration showed maxima over the high emission areas, such as North China Plain, Yangtze River Delta, and Sichuan Basin in China and densely populated regions in Korea and Japan. In fact, the cluster analysis, provided by Hayashida et al.15, proved that the locations of a high OMI-O3 cluster matched with the high NOx emission areas. In the month, the Pacific High pressure system was dominant and the clean maritime air was transported from the south to the Northwestern Pacific. During the summer, the Pacific High blocks the long-range transport due to the mid-latitude westerlies in the region. Figure 1b shows the simulated 0–3 km mean O3 concentration (ppb; Δx = 30 km). Due to the prevailing mid-latitude westerlies at upper altitudes, the high concentration areas extend farther eastward compared to the surface concentrations. Figure 1c shows the simulated OMI-time 0–3 km mean O3 column amount (DU; Δx = 1°), convolved with the retrieval averaging kernels (AKs) (denoted as simulated O3 with AK, hereinafter) (see Eq. (1)), which can be quantitatively compared with the OMI-O3 as shown in Fig. 1d. The “simulated OMI-time” indicates simulation results at 6 UTC (13:40 local time at the center of model domain (115 °E)), while the OMI observation time is 13:45 local time. The spatial distributions of Fig. 1b,c are drastically different due to the following reasons: (1) influences of O3 from the above layers and (2) exclusion of cloudy/rainy days and days under the influence of stratospheric O3 intrusion due to the tropopause perturbations. In order to clearly show the effects, two more panels (OMI-time O3 before and after screening for clouds and stratospheric inclusion) are added to Fig. 1 as illustrated in Fig. S1 in the supplement. The “simulated OMI-time 0–3 km O3” means that after the screening in this paper.

Figure 1.

Monthly mean simulated and observed lower tropospheric O3. (a,b), The monthly mean simulated surface and 0–3 km mean O3 mixing ratio (ppb) together with wind vectors in June 2006. c, The monthly mean simulated OMI-time 0–3 km O3 column amount (DU) with AK and d, OMI-observed 0–3 km O3 column amount (DU). The dashed box indicates the analysis area of the study (110–146°E, 30–45°N) and the hatched area indicates the grids where the retrieved OMI-O3 is significantly larger than the a priori (climatological) O3 at a one-sided 95% confidence interval. The spatial resolution Δx of (a,b) is 30 km, whereas Δx of (c,d) is 1 degree.

The Student’s t-test was applied for the monthly mean OMI-O3 and the a priori O3 using the daily values in June 2006. Degrees of freedom at each grid point are the number of available data in the month minus one, i.e., up to 29. The hatched area of Fig. 1d indicates the grids where the OMI-O3 was significantly larger than the a priori O3 at a one-sided 95% confidence interval. Most of the O3 rich regions (i.e., >12 DU) are statistically significant. For the emission reduction test as presented later, data in the hatched area inside the dashed box (110–146°E, 30–45°N) were used for the analysis.

The same horizontal distribution with a different confidence interval, two-sided 99%, is presented in Fig. S2, in the supplement. Over the relatively low concentration areas such as Sichuan Basin, Korea, and Japan, the hatched areas become small or disappeared. In contrast, over the high concentration areas such as North China Plain and Yangtze River Delta, the difference between the OMI-O3 and the a priori O3 remained significant at this confidence interval, due to substantially large near-surface photochemical O3 production.

Comparison between observation and simulation

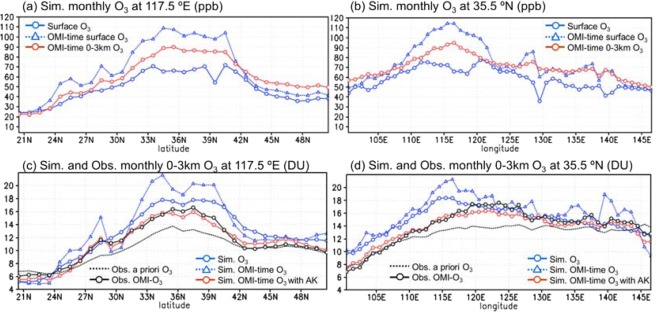

In order to compare the spatial distributions of the simulation (Fig. 1c) and the observation (Fig. 1d), as shown in Fig. 2, the cross sections of the simulated and observed O3 at 117.5°E and 35.5°N are compared, in order to cover the areas, where O3 enhancement was observed by the satellite retrieval, namely, the North China Plain and populated and industrial regions in Korea and Japan.

Figure 2.

Cross sections of monthly mean simulated and observed lower tropospheric O3. The cross sections of monthly mean (a,b), surface O3 mixing ratio (ppb) and (c,d), 0–3 km O3 column amount (DU) at (a,c), 117.5°E and (b,d), 35.5°N. a,b, The blue solid and dashed lines indicate the monthly mean values of simulated hourly O3 and OMI-time O3, respectively. The red line indicates the monthly mean OMI-time 0–3 km averaged O3 (after the screening). (c,d) The black solid and dashed lines indicate the retrieved OMI-O3 and the a priori O3 used for the retrieval, respectively. The blue solid and dashed lines indicate the monthly mean values of simulated hourly O3 and OMI-time O3 (after the screening), respectively. The red line indicates the monthly mean simulated OMI-time 0–3 km O3 column amount with AK.

The upper panels of Fig. 2 show the monthly mean values of simulated hourly surface O3 (blue, solid), O3 at the OMI observed time (blue, dashed), and 0–3 km mean O3 at the OMI time (red, solid). The surface mean OMI-time O3 was significantly larger by more than 30 ppb than the mean of hourly O3 over the area with the abundant presence of emission of precursor gases (30–40°N, 110–120°E). This daytime enhancement was smaller for 0–3 km mean O3 but still significant: the 0–3 km mean OMI-time O3 was larger by 10–20 ppb over the high emission area. On the other hand, over the low emission area or over the ocean, the 0–3 km mean OMI-time O3 was even larger than the surface OMI-time O3 due to the absence of photochemical production near the surface. In such areas, the daytime O3 enhancement was not detected by the satellite and thus no statistical significance was found between the a priori and retrieved O3.

The lower panels of Fig. 2 show the monthly mean values of simulated 0–3 km column amount of hourly O3 (blue, solid), O3 at the OMI time (blue, dashed), and O3 at the OMI time with AK (red, solid). The monthly mean OMI-time O3 was 1–4 DU larger than the monthly mean of hourly O3 over the large emission areas, but the absolute values of monthly simulated OMI-time O3 with AK were even lower than the monthly mean of hourly O3, due to the reasons presented later with Eq. (1). Still, the important things here are that the simulated OMI-time O3 with AK agreed well with the OMI-O3 (black, solid) (generally smaller than 0.5 DU over the high emission areas) and that the both simulated and observed O3 were significantly larger than the a priori O3 (black, dashed) over the high emission areas. The spatial correlation coefficient between the simulated and observed monthly values over the hatched area in the dashed box shown in Fig. 1d was 0.94.

Sensitivity to emission changes and statistical significance

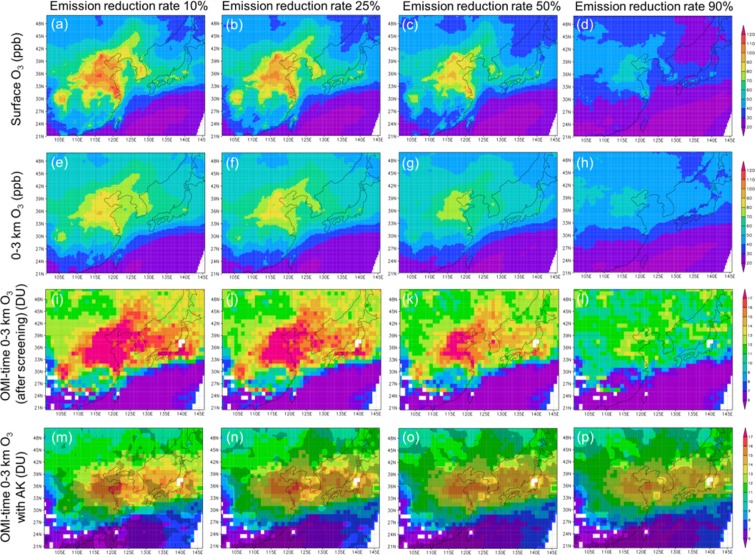

Figure 3 shows the monthly mean simulated (top to bottom) surface O3, 0–3 km mean O3, OMI-time 0–3 km O3 after the screening, and that with AK at the reduction rates of anthropogenic precursor gases emissions of (left to right) 10%, 25%, 50%, and 90%. The contrasts between the results with 10% and 90% reductions become gradually smaller from surface O3, 0–3 km O3, to OMI-time 0–3 km O3 with AK. For the simulated 0–3 km O3 with AK, even though the differences looked small, the differences between the emission reduction simulations and the control run (i.e. 0% emission reduction simulation; Fig. 1c) were statistically significant at a one-sided 95% confidence interval (the Student’s t-test), as indicated by the hatched areas in Fig. 3m–p. The significance areas became larger as the emission reduction rates were larger. (The same figures without the hatched areas are presented in Fig. S3 to make the results more visible.)

Figure 3.

Simulated lower tropospheric O3 responses to its precursor emission changes. The monthly mean simulated (top to bottom) surface O3 (ppb), 0–3 km mean O3 (ppb), OMI-time 0–3 km O3 column amount (after the screening) (DU), and OMI-time 0–3 km O3 column amount with AK (DU) at the different emission reduction levels of the precursor gases, (left to right), 10%, 25%, 50%, and 90% of the control level. The hatched areas indicate the grids where the simulated O3 with AK is significantly smaller than that for the control level of precursor gases emissions at a one-sided 95% confidence interval.

The same horizontal distribution with a different confidence interval, two-sided 99%, is presented in Fig. S4, in the supplement. Similar to the differences between the two confidence intervals as shown in Fig. S2, the hatched areas become smaller with the two-sided 99%, but still cover the high concentration areas such as North China Plain and Yangtze River Delta. The most of the high concentration areas are covered with the hatched areas for the emission reduction rates greater than 25% in Fig. S4f – S4h.

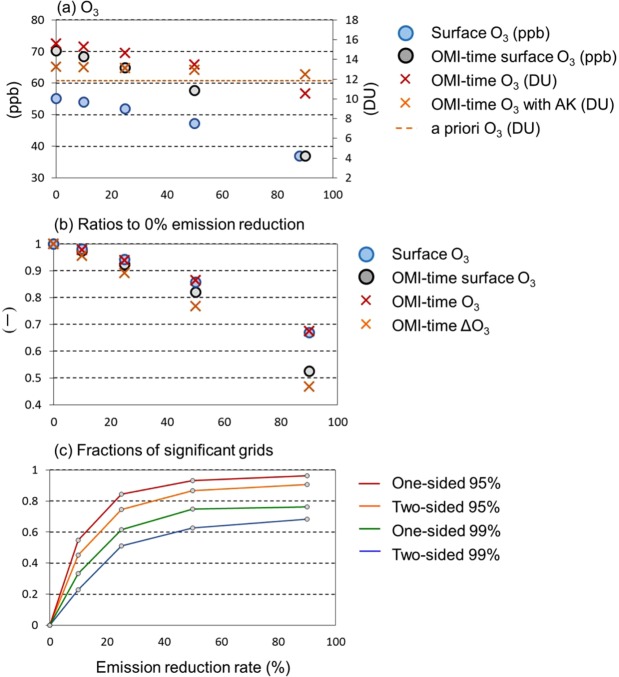

Figure 4 shows areal statistics of the horizontal distributions over the hatched regions in the dashed box of Fig. 1d: the monthly mean OMI-O3 was significantly larger than the a priori O3 over 110–146°E and 30–45°N. Some important values in the figure are presented in Table S1. Here we define ΔO3. The difference between the OMI-O3 and the a priori O3 is denoted as OMI-ΔO3, which can be regarded as a satellite-detectable O3. Also derived and discussed is the simulated ΔO3 (or simply referred to as ΔO3), which is the simulated O3 with AK minus the a priori O3 used for the retrieval. ΔO3 can be regarded as a simulated satellite-detectable O3.

Figure 4.

Summary of lower tropospheric O3 responses to its precursor emission changes. (a) The monthly and areal averaged simulated O3 over the areas where the retrieved OMI-O3 were significantly larger than the a priori O3 (as hatched in Fig. 1d) at the different reduction ratios of the precursor gases emissions (0%, 10%, 25%, 50%, and 90%). (b) Same as (a) but the ratios to the values at the emission reduction of 0%. (a,b) The blue and black symbols indicate the mixing ratios of surface hourly O3 and OMI-time O3 (left axis, ppb), respectively. The red and orange symbols indicate the OMI-time 0–3 km column amounts (after the screening) and that with AK (right axis, DU), respectively. The orange dashed line indicates the areal mean a priori O3 column amount. c, The blue, green, orange, and red lines indicate the areal fractions at different confidence intervals, two-sided 99%, one-sided 99%, two-sided 95%, and one-sided 95%, respectively.

Figure 4a,b show the areal and monthly mean simulated O3 and their ratios to those at 0% emission reduction, respectively. The black and blue symbols indicate the means of hourly and OMI-time surface O3, respectively. The daytime enhancement (black minus blue) was 15 ppb at 0% emission reduction due to the local photochemical productions, which was almost 0 ppb at 90% due to the absence of anthropogenic emissions of precursor gases. O3 level at 90% reduction rates can be almost regarded as the background level (or the contributions from the hemispheric transport11), approximately 35 ppb for surface O3 and 10 DU for 0–3 km column of O3. As shown in Fig. 4b, the decreasing rate of the OMI-time surface O3 (approximately 50% at 90% reduction) is larger than that of hourly surface O3 (approximately 70% at 90% reduction). The 0–3 km OMI-time column amount (red) decreased by 2.3, 6.1, 14, and 33% (Fig. 4b, Table S1) due to the emission reductions of 10, 25, 50, and 90%, respectively. This decreasing trend of the 0–3 km OMI-time column amount (red) was smaller than that of surface OMI-time concentration (black) and as small as that of the surface hourly concentration (blue). The decreasing trend of OMI-time O3 with AK (orange in Fig. 4a) is very small, but that of simulated ΔO3 (orange in Fig. 4b), i.e., OMI with AK (orange cross) minus the a priori OMI (orange dashed; 11.83 DU), is as large as surface OMI-time O3 (Fig. 4b): The ΔO3 was reduced to 47% at 90% reduction (Table S1). Therefore, even though the decreasing trend of O3 with AK was small, the simulated O3 with AK of various emission reduction simulations were significantly smaller than that at 0% reduction simulation, in substantial fractions of the domain (Fig. 4c). The fractions of significant areas at the emission reduction rates of 10%, 25%, 50%, and 90% to the hatched area in Fig. 1d are 55, 84, 93, and 96% at a one-sided 95% confidence interval (red) and 23%, 51%, 63%, and 68% at a two-sided 99% confidence interval (blue), respectively (Fig. 4c).

By using a recently developed satellite product12,13 and a regional meteorology – chemistry model18, we concluded that the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) sensor can detect summer-time lower tropospheric O3 responses due to reductions of emissions of anthropogenic precursor gases, NOx and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs), in East Asia, despite the abundant presence of stratospheric and upper tropospheric O3. A socio-economic future emission scenario study22 estimated approximately 50% reduction in the global NOx emission in 2100 with compared to the year 2000, and even higher reduction rates up to 80% for additional climate mitigation cases. For such reduction cases greater than 50%, the satellite sensor could detect lower tropospheric O3 changes over substantially large areas (Fig. 4c). The current study showed usefulness and importance of monitoring future O3 trend by satellite sensors. The same reduction rates between NOx and NMVOC emissions are unlikely in reality, as the emission sources of the two components are very different. The realistic emission scenario needs to be applied in the future beyond the current study. Recently, TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI23) has been onboard to the Copernicus Sentinel-5 Precursor (S5p) satellite. Because of the recent advancement of satellite sensor technologies, study on tropospheric photochemistry will be rapidly advanced in the near future, together with other technologies such as in-situ/remote measurements and numerical simulations.

Methods

OMI-retrieved lower tropospheric O3 product

The retrieval methodology and the usage of lower tropospheric O3 product are described in detail in Hayashida et al.14,15. We used the data obtained from the OMI sensor, a Dutch-Finnish-built nadir-viewing UV/visible instrument, carried by the Aura spacecraft of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Earth Observing System (EOS) in a sun-synchronous orbit with an equatorial crossing time of ~13:45 local time. The O3 profiles are retrieved by Liu et al.12 with several modifications described in Kim et al.19, from the ground upward to approximately 60 km in 24 layers, of which 3–7 layers are in the troposphere. To constrain the retrievals, they used climatological zonal mean O3 profiles and standard deviations derived from 15 years of ozonesonde measurements and the Stratospheric Aerosol and Gas Experiment (SAGE) as a priori data17, which vary with altitude, month, and latitude. The retrieval was performed at a nadir resolution of 52 km × 48 km by adding 4/8 UV1 (270–310 nm) /UV2 (310–365 nm) pixels. In the current study, we use the Level 3 product gridded to 1° × 1° (latitude × longitude) spatial resolution on a daily basis. The gridded data were screened using the effective cloud fraction (ECF) < 0.2 and RMS (root mean square of the ratio of the fitting residual to the assumed measurement error of the UV2 channel) < 2.4 criteria13. The retrieved O3 in the lower tropospheric layers was found to be affected by outstanding O3 enhancement along with the sub-tropical jet due to the intrusion of the stratospheric O313. This artifact was successfully screened out by the method developed by Hayashida et al.13,14. In order to validate their product, Hayashida et al.13 compared OMI-O3 against the in-situ airborne measurements, the Measurement of Ozone and Water Vapor by Airbus In-Service Aircraft (MOZAIC) program. Currently, it has been renamed to the Integration of Routine Aircraft Measurements into a Global Observing System (IAGOS) and the data is available at http://www.iagos.fr, last access: 2 November 2019). They found statistically-significant positive correlation for the 0–3 km OMI-O3 and that of IAGOS at Beijing from 2004 to 2005, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis for comparing OMI, NHM-Chem, and the in-situ measurements for 0–3 km O3.

| Product to be evaluated (y) | OMIa | NHM-Chemb | NHM-Chemc |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-situ measurement (x) | IAGOSa | IAGOSb | ozonesondec |

| Number of data | 36 | 65–309 | 80–94 |

| Unit | DU | ppb | ppb |

| Linear regression | y = 0.33x + 6.72 | —d | —d |

| R | 0.82 | 0.49–0.72 | 0.54–0.82 |

| Observed average () | n.a. | 38.2–55.8 | 34.0–45.9 |

| Mean bias () | n.a. | −1.76–5.2 | −3.52–7.94 |

aAt Beijing airport for 2004–2005 (Hayashida et al.13).

bRanges from four airports, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Osaka, and Tokyo for 2005–2006 (this study).

cRanges from four stations, Hong Kong, Naha, Tsukuba, and Sapporo for 2005–2006 (this study).

cLinear regression was not presented in this study. The mean bias and observed average values were presented instead.

After validation using the other in situ and satellite measurements, the 10 year product (October 2004 – December 2014) was published, referred to as the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) OMI Ozone Profile (OMPROFOZ)12,19–21. Currently, the dataset (V0.9.3) with updates (until September 2019) is available at https://avdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/index.php?site=1389025893&id=74 (last access: 4 November 2019). The data used in the study is equivalent to that V0.9.3.

A regional-scale meteorology – chemistry model

A regional-scale meteorology – chemistry model, NHM-Chem18, was used to simulate tropospheric O3 over East Asia. Among the three aerosol representation options employed in NHM-Chem, the bulk equilibrium method was selected in this study. The method is computationally efficient but found to be accurate enough for the prediction of mass concentrations18.

The simulation settings such as model domain, simulation period, and boundary conditions are the same as Kajino et al.18 and thus the details are refrained from repeating. The model domain covers East Asia with 200 × 140 horizontal grid cells with a resolution of Δx = 30 km. The number of grid cells of NHM and CTM were 38 (reaching up to 22,055 m M.S.L.) and 40 (reaching up to 18,000 m M.S.L), respectively, with the terrain-following coordinates. The 3-hourly lateral and upper boundary concentrations of O3 and its precursors were obtained from the simulation results of the global stratospheric and tropospheric chemistry – climate model (MRI-CCM224). We used REASv24 for the anthropogenic emissions. The simulation was made for the whole year of 2006, but the analysis was conducted for a month, June 2006, when the monthly mean lower-tropospheric OMI-O3 over East Asia was highest in the year. In order to synchronize the OMI observation time (13:45 local time) with the hourly model output time, the simulation results at 6 UTC, which is 13:40 local time at the center of model domain (115°E), were used for the comparison.

Because Kajino et al.18 only provided model evaluation for surface concentrations, the comparison of the simulated and observed 0–3 km mean concentrations were conducted as shown in Table 1. Because the IAGOS measurement at Beijing ended November of 2005 and no data are available for 2006, we compared the simulation results against the other East Asian airports such as Hong Kong, Shanghai, Osaka, and Tokyo for 2006. In order to increase the number of data, we also drove NHM-Chem for 2005 and compared the results against the observation. We also used the ozonesonde data, conducted by the Global Atmospheric Watch (GAW) program of World Meteorological Organization (WMO) for the model evaluation. The ozonesonde data is available at https://woudc.org/data/explore.php (last access: 2 November 2019). As shown in Table 1, the simulation results showed good agreements with the both in-situ measurements.

In addition to Kajino et al.18, we conducted sensitivity simulations of anthropogenic emission of O3 precursors such as NOx and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs). We have totally five sets of simulations, with 0%, 10%, 25%, 50%, and 90% reductions from the emission flux of the year 2006. The same reduction rates were applied for both NOx and NMVOCs. Note that the same reduction rates were unlikely in reality as the emission sources of the both species are quite different.

In order to compare against the OMI data, the simulation results were spatially allocated to the grids of the OMI products, which were horizontally 1° × 1° (latitude × longitude) with vertically approximately 3 km intervals. Then, we applied the OMI retrieval averaging kernels (AKs) (rows) to the simulation results for the consistent comparison as follows:

| 1 |

where is the simulated O3 column amount (DU) at j-th OMI vertical grid, convolved with the retrieval AKs (A(i, j)), denoted as O3 “with AK”. Xt,i is the simulated O3 column amount at i-th OMI vertical grid and Xa is the a priori profile used in the OMI retrievals. We applied Eq. (1) to the simulation results only for i = 22, 23, and 24, (i.e., lower than approximately 9 km above ground level, within the troposphere) and we used the OMI-retrieved data for Xt,i above the 21st layer because NHM-Chem is a tropospheric chemistry model.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was mainly supported by the Fundamental Research Budget of MRI (M5, P5), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP16H04051 and Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN: a constituent member of NIHU) Project No.14200133 (Aakash), and partly supported by the Integrated Research Program for Advancing Climate Models (TOUGOU Program) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology Japan (MEXT), and the Environmental Research and Technology Development Fund (5-1605) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency (ERCA). The authors feel obliged to thank Ms. H. Araki for their support on data analysis and handling.

Author contributions

M.K. designed the research and conducted the numerical simulations. M.K. wrote the manuscript with collaborations of S.H., T.T.S., M.D. and X.L. K.I. and M.K. made the model evaluations and produced the figures. S.H. and X.L. produced and provided the OMI data products.

Data availability

Data used in Figs. 1–4 and Table 1 are available at https://mri-2.mri-jma.go.jp/owncloud/index.php/s/jGm7cHGVXc8Bp9f. Other data are available upon request to the corresponding author (M.K.).

Code availability

The NHM-Chem source code is available subject to a license agreement with the Japan Meteorological Agency. Further information is available at http://www.mri-jma.go.jp/Dep/ap/nhmchem_model/application.html. Unfortunately, this website is only in Japanese. Thus additionally, the source code, user’s manual, analysis tools, and sets of boundary conditions can be provided upon request to the corresponding author (M.K.).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-55759-7.

References

- 1.US-EPA, Air Quality Criteria for Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidant, Vol. I, II, III, US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA, EPA/600/R-05/004aF,bF,cF (2016).

- 2.IPCC, Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G. –K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., & Midgley, P. M. (eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp. (2013).

- 3.Akimoto H. Global air quality and pollution. Science. 2003;302:1716–1719. doi: 10.1126/science.1092666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurokawa J, et al. Emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases over Asian regions during 2000–2008: Regional Emission inventory in ASia (REAS) version 2. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013;13(11):019–11,058. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper OR, et al. Global distribution and trends of tropospheric ozone: An observation-based review. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. 2014;2:000029–28 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan B, et al. A space-based, high-resolution view of notable changes in urban NOx pollution around the world (2005–2014), J. Geophys. Res. 2016;121:976–996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krotkov NA, et al. Aura OMI observations of regional SO2 and NO2 pollution changes from 2005 to 2015. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016;16:4605–4629. doi: 10.5194/acp-16-4605-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu X, et al. Increasing ammonia concentrations reduce the effectiveness of particle pollution control achieved via SO2 and NOx emissions reduction in East China. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017;4(6):221–227. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.7b00143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Lee CS, Zhang R, Chen L. Spatial and temporal evaluation of long term trend (2005–2014) of OMI retrieved NO2 and SO2 concentrations in Henan Province, China. Atmos. Environ. 2017;154:151–166. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.11.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kannari A, Ohara T. Theoretical implication of reversals of the ozone weekend effect systematically observed in Japan. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010;10:6765–6776. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-6765-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagashima T, Ohara T, Sudo K, Akimoto H. The relative importance of various source regions on East Asian surface ozone. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010;10(11):305–11,322. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Bhartia PK, Chance K, Spurr RJD, Korusu TP. Ozone profile retrievals from the ozone monitoring instrument. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010;10:2521–2537. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-2521-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashida S, Liu X, Ono A, Yang K, Chance K. Observation of ozone enhancement in the lower tropospheric over East Asia from a space-borne ultraviolet spectrometer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15:9865–9881. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-9865-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashida, S. et al. Study of lower tropospheric ozone over central and eastern China: comparison of satellite observation with model simulation. In: Vadrevu, Krishna Prasad, Ohara, Toshimasa, Justice, Chris (Eds.), Land-Atmospheric Research Applications in South and Southeast Asia. Springer Remote Sensing/Photogrammetry, 255–275 (2018a).

- 15.Hayashida S, Kajino M, Deushi M, Sekiyama TT, Liu X. Seasonality of the lower tropospheric ozone over China observed by the Ozone Monitoring Instrument. Atmos. Environ. 2018;184:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen L, et al. An evaluation of the ability of the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) to observe boundary layer ozon pollution across China: application to 2005–2017 ozone trends. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019;19:6551–6560. doi: 10.5194/acp-19-6551-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McPeters RD, Labow GJ, Logan JA. Ozone climatological profiles for satellite retrieval algorithms. J. Geophys. Res. 2007;112(1–9):D05308. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kajino M, et al. NHM-Chem, the Japan Meteorological Agency’s regional meteorology – chemistry model: model evaluations toward the consistent predictions of the chemical, physical, and optical properties of aerosols. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan. 2019;97(2):337–374. doi: 10.2151/jmsj.2019-020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim PS, et al. Global ozone-CO correlations from OMI and AIRS: constraints on tropospheric ozone sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013;13:9321–9335. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-9321-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang G, et al. Valication of 10-year SAO OMI Ozone Profile (PROFOZ) product using ozonesonde observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017;10:2455–2475. doi: 10.5194/amt-10-2455-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang G, Liu X, Chance K, Yang K, Cai Z. Validation of 10-year SAO OMI ozone profile (PROFOZ) product using Aura MLS measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018;11:17–32. doi: 10.5194/amt-11-17-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao S, et al. Future air pollution in the Shared Socio-economic Pathways. Global Environ. Chang. 2017;42:346–358. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veefkind JP, et al. TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel-5 Precursor: A GMES mission for global observations of the atmospheric composition for climate, air quality and ozone layer applications. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2012;120:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2011.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deushi M, Shibata K. Development of an MRI Chemistry-Climate model ver.2 for the study of tropospheric and stratospheric chemistry. Papers in Meteorology and Geophysics. 2011;62:1–46. doi: 10.2467/mripapers.62.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used in Figs. 1–4 and Table 1 are available at https://mri-2.mri-jma.go.jp/owncloud/index.php/s/jGm7cHGVXc8Bp9f. Other data are available upon request to the corresponding author (M.K.).

The NHM-Chem source code is available subject to a license agreement with the Japan Meteorological Agency. Further information is available at http://www.mri-jma.go.jp/Dep/ap/nhmchem_model/application.html. Unfortunately, this website is only in Japanese. Thus additionally, the source code, user’s manual, analysis tools, and sets of boundary conditions can be provided upon request to the corresponding author (M.K.).