Abstract

Previous studies have shown that lipid metabolism in granulosa cells (GCs) plays a vital role during mammalian ovarian follicular development. However, little research has been done on lipid metabolism in avian follicular GCs. The goal of the present study was to investigate the dynamic characteristics of lipid metabolism in GCs from geese pre-hierarchical (6–10 mm) and hierarchical (F4-F2 and F1) follicles during a 6-day period of in vitro culture. Oil red O staining showed that with the increasing incubation time, the amount of lipids accumulated in three cohorts of GCs increased gradually, reached the maxima after 96 h of culture, and then decreased. Moreover, the lipid content varied among these three cohorts, with the highest in F1 GCs. The qPCR results showed genes related to lipid synthesis and oxidation were highest expressed in pre-hierarchical GCs, while those related to lipid transport and deposition were highest expressed in hierarchical GCs. These results suggested that the amount of intracellular lipids in GCs increases with both the follicular diameter and culture time, which is accompanied by significant changes in expression of genes related to lipid metabolism. Therefore, it is postulated that the lipid accumulation capacity of geese GCs depends on the stage of follicle development and is finely regulated by the differential expression of genes related to lipid metabolism.

Keywords: Follicle development, Goose, Granulosa cell, Lipid metabolism

Introduction

As the critical component of ovarian follicles, GCs play a pivotal role during follicular development and oocyte maturation [1–4]. Previous functional studies on GCs were mainly focused on proliferation, apoptosis and steroidogenesis [5–8]. Whereas, it has been recently reported that lipid metabolism in bovine, sheep and human GCs is also important for follicular development [9–11]. Investigations of lipid profile in both follicular cells (including cumulus, granulosa and theca cells) and follicular fluid by mass spectrometry (MS) suggest that lipid metabolism is pivotal for follicular development and oocyte maturation [12–16]. Additionally, glucose is known as the main energy source for the oocyte [17], since the oocyte has a limited capacity to utilize glucose and the substrates such as pyruvate and lactate are main energy sources metabolized by GCs [18,19]. Thus, lipid metabolism in GCs is considered to be indispensable for oocyte maturation.

By comparing the transcriptomic profiling of bovine cumulus cells (CCs, a type of GCs) isolated from ovaries before and after oocyte maturation, 27 genes related to lipogenesis, lipolysis, fatty acid transport and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) are identified [20], and 22 of them were significantly up-regulated from the phase of germinal vesicle breakdown to metaphase-II during in vitro maturation [20]. Furthermore, inhibitors of FAO (e.g. etomoxir) decreased the maturation rate of in vitro cultured oocytes in a dose-dependent manner by decreasing expression of lipogenic genes and increasing that of lipolytic and FAO-related genes [20,21]. Similarly, in bovine GCs, pharmacological inhibition of the enzymatic activity of fatty acid synthase using its specific inhibitors C75 significantly reduced the production of progesterone, suggesting that ovarian steroidogenesis relies on lipid metabolism in GCs [9,22]. In support of this, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ (PPARG), a key transcriptional factor regulating lipid metabolism, was widely expressed in rat, buffalo and sheep GCs, and was shown to participate in the synthesis of steroid hormones by modulating the aromatase activity [23–25]. These results suggested that lipid metabolism is important for follicular maturation by regulating cellular energy metabolism, proliferation, apoptosis and steroid hormone synthesis.

Changes in lipids have shown that the total lipid content increased with the growth of follicles (including early antral, small antral, medium antral, large antral, pre-ovulatory, ovulatory follicle) in goat ovary by biochemical quantitative [26]. Morphological observation also showed lipid droplet changed in shape from small and black to large and gray and its number increased in both oocyte and GCs as the follicles develop in mammals [27–29]. Our recently published study demonstrated that de novo lipogenesis (DNL) exists in goose ovarian follicles, especially in GCs [30]. Additionally, previous studies on avian GCs indicated that GCs change in their morphological and functional characteristics with the maturation of ovarian follicles. For instance, the number of GCs as well as their thickness and surface area change among avian follicles at different developmental stages [31,32] and the shape of GCs changes from flatten to cuboidal during follicle development [32]. Meanwhile, GCs are maintained in an undifferentiated state before being selected into the preovulatory hierarchy, and are active in mitosis but have weak steroidogenic ability [33,34]. And the pre-hierarchical GCs are more prone to undergo apoptosis than the hierarchical GCs [31,35]. Furthermore, the maturation of avian follicles is accompanied with the accumulation of yolk [36], and the major component of yolk is lipid. Taken together, we speculated that lipid metabolism in GCs is associated with the stage of follicle development in birds.

Therefore, the present study aimed to reveal differences in the dynamic characteristics of lipid deposition in the three cohorts of in vitro cultured GCs from geese follicles at different developmental stages and to investigate the expression profiles of a series of lipid metabolism-related genes in these GCs. These data are expected to lay a foundation for future research on follicular lipid metabolism and the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Tianfu meat geese, at the age of 35–45 weeks and laying in regular sequences of at least 2–3 eggs, were used in the present study. Geese were kept under natural conditions of temperature and light and had free access to food and water at the Experimental Farm of Waterfowl Breeding of Sichuan Agriculture University (Sichuan, China). Individual laying patterns were recorded on a daily basis. The healthy geese were killed by cervical dislocation 6–8 h ahead of oviposition. All procedures described herein were conducted according to the Guide of the Faculty Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University (Sichuan, China).

Isolation and culture of GCs

Follicles were rapidly dissected from each ovary and were then washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China). These follicles were classified into pre-hierarchical (<10 mm) and hierarchical (designated as F5-F1) follicles, and three cohorts of them including the pre-hierarchical (6–10 mm), F4-F2 and F1 follicles were further selected for isolation of GCs based on our previously protocol [35,37]. GCs isolated from each cohort were digested with 0.1% collagenase (sigma, Aldrich, U.S.A.), counted using the Handheld Automated Cell Counter (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA 01821). The GCs were seeded at a density of ∼3 × 105 cells/well (12-well plate) and cultured as previously described [35], and these cells were used for Oil red O staining and qPCR.

Oil red O staining and morphological observation

The amount of lipids accumulated in GCs was evaluated using the Oil red O staining method according to a previously described protocol with slight modification [38]. In brief, after being washed three times with PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) for 1 h. Then, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and were subsequently stained with Oil red O (Sigma, ST. Louis, United States) in the dark for 1 h at room temperature. Thereafter, cells were washed with PBS and photographed using a phase contrast microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Finally, isopropanol was added into wells to extract Oil red O that transferred to 96-well plates and subjected to determination of optical density (OD) value at 490 nm using the automatic enzyme immunoassay analyzer.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from each sample using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.), according to the manufacture’s instruction. The RNA quality, purity and concentration were using gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometric absorbance measurement. Equal amount of total RNA (1 μg) from each sample was reversely transcribed into cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit following the manufacture’s instruction (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan).

Quantitative real-time PCR

The mRNA expression levels of those genes of interest were detected by quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) using the SYBR PrimerScriptTM RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). The qRT-PCR reactions were conducted in a 12.5 μl volume (containing 1 μl cDNA, 6.25 μl of SYBR PremixEX Taq, 4.25 μl of sterile water and 1 μl of primers) and were run on the CFX96TMReal-Time System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.). The qRT-PCR procedures included 95°C for 10 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s imposing the annealing temperature for 30 s and at 72°C for 10 min. An 80-cycle melting curve was performed, starting at a temperature of 65°C and increasing by 0.5°C every 10 s to determine primer specificity. Each sample was conducted in triplicate and the relative mRNA level for genes were normalized by β-actin and 18 s rRNA using 2−ΔΔCt method [39]. Primer used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Primer pairs for real-time quantitative PCR.

| Genes | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Tm (°C) | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| accα | TGCCTCCGAGAACCCTAA | AAGACCACTGCCACTCCA | 60 | 163 |

| fasn | TGGGAGTAACACTGATGGC | TCCAGGCTTGATACCACA | 60 | 109 |

| dgat1 | CCTGAGGAACTTGGACACG | CAGGGACTGGTGGAACTCG | 59 | 265 |

| dgat2 | CGCCATCATCATCGTGGT | CGTGCCGTAGAGCCAGTTT | 59 | 113 |

| cpt1 | GTCTCCAAGGCTCCGACAA | GAAGACCCGAATGAAAGTA | 56 | 193 |

| atgl | TCGCAACCTCTACCGCCTCT | TCCGCACAAGCCTCCATAAGA | 60 | 300 |

| apob | CTCAAGCCAACGAAGAAG | AAGCAAGTCAAGGCAAAA | 56 | 153 |

| mttp | CCCGATGAAGGAGAGGAA | AAAATGTAACTGGCCTGAGT | 56 | 85 |

| srebp1 | CGAGTACATCCGCTTCCTGC | TGAGGGACTTGCTCTTCTGC | 60 | 92 |

| pparβ | TGACGGCGAGCGAGAT | CAGGTAGGCGTTGTAGATGTG | 60 | 83 |

| pparγ | CCTCCTTCCCCACCCTATT | CTTGTCCCCACACACACGA | 59 | 108 |

| β-actin1 | CAACGAGCGGTTCAGGTGT | TGGAGTTGAAGGTGGTCTCG | 60 | 92 |

| 18 S1 | TTGGTGGAGCGATTTGTC | ATCTCGGGTGGCTGAACG | 60 | 129 |

Houskeeping gene for data normalization.

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) of three independent experiments. All data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and differences among the means were assessed for significance by Duncan’s multiple range test using SPSS (IBM, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

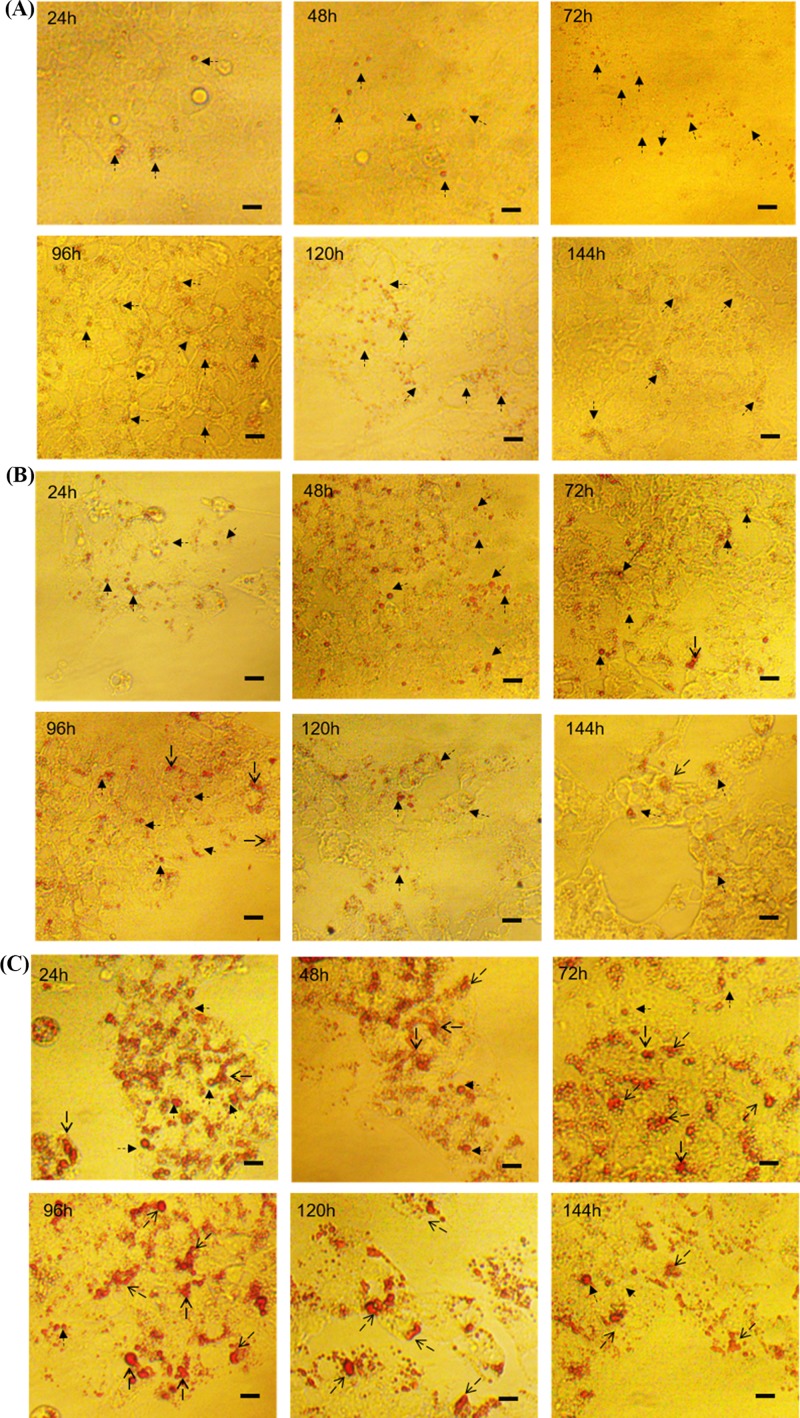

Dynamic changes in morphological characteristics of lipid droplets among different cohorts of in vitro cultured GCs

Changes in the morphology of lipid droplets among three cohorts of GCs isolated from follicles at different stages of development were evaluated using Oil red O staining and are shown in Figure 1. Morphological changes in lipid droplet were manifested by fusing with each other, and its size changed after fusion. With increasing incubation time, the pre-hierarchical GCs began to form smaller lipid droplets, which were generally spherical in shape. By contrast, both the F4-F2 and F1 GCs tended to form relatively larger lipid droplets, which were shown as spherical or irregular. Additionally, after Oil red O staining, the color of lipid droplets was generally brighter in the F1 GCs compared with the other two cohorts. Because the color intensity reflected the levels of triglycerides and cholesterol within lipid droplets, these data demonstrated that higher levels of lipids were accumulated in the hierarchical than pre-hierarchical GCs.

Figure 1. Morphological characteristics of lipid droplets in vitro cultured GCs.

Panels (A–C) represent the pre-hierarchical, F4-F2 and F1 GCs, respectively. The thin arrows represent round lipid droplets, and triangular arrows represent irregular lipid droplets owing to fusion. The scale marker represents 50 μm.

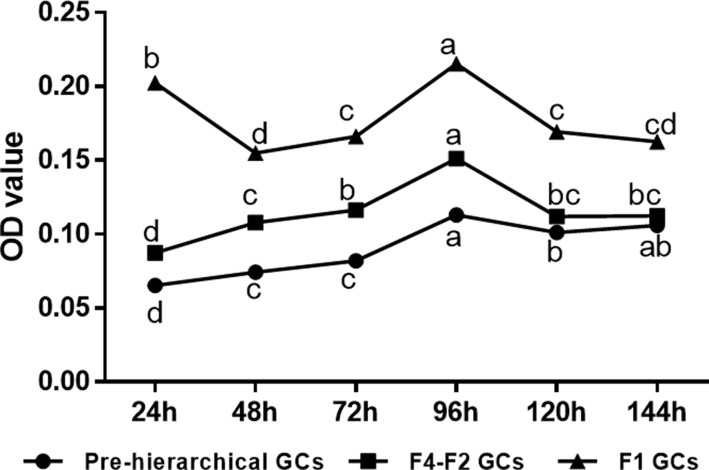

Dynamic changes in the content of intracellular lipids among different cohorts of in vitro cultured GCs

Intracellular lipids within GCs were measured by Oil red O extraction. As shown in Figure 2. we found that large amounts of lipids were deposited into three cohorts of GCs after 24 h of in vitro culture. Furthermore, with the extension of incubation time, the amount of lipids accumulated in three cohorts of GCs increased gradually, reached the maxima at 96 h culture, and then decreased. Greater amount of intracellular lipids was found in hierarchical than pre-hierarchical GCs (P < 0.05) except the observation that during the incubation period from 120 to 144 h the F4-F2 and 6–10 mm GCs accumulated similar amount of lipids. Noticeably, an abrupt decline in intracellular lipids was seen in the F1 GCs at 48 h of culture. The results of Oil red O extraction indicated that a greater amount of lipids was shown to be accumulated in the F1 GCs compared with the other two cohorts throughout the incubation period, and the F4-F2 GCs appeared to have much higher ability than the 6–10 mm GCs in the accumulation of lipids.

Figure 2. Intracellular lipid deposition of three cohorts of in vitro cultured GCs.

Different lowercase letters indicate the significant differences among different culture time within the same cohort of cells (P < 0.05).

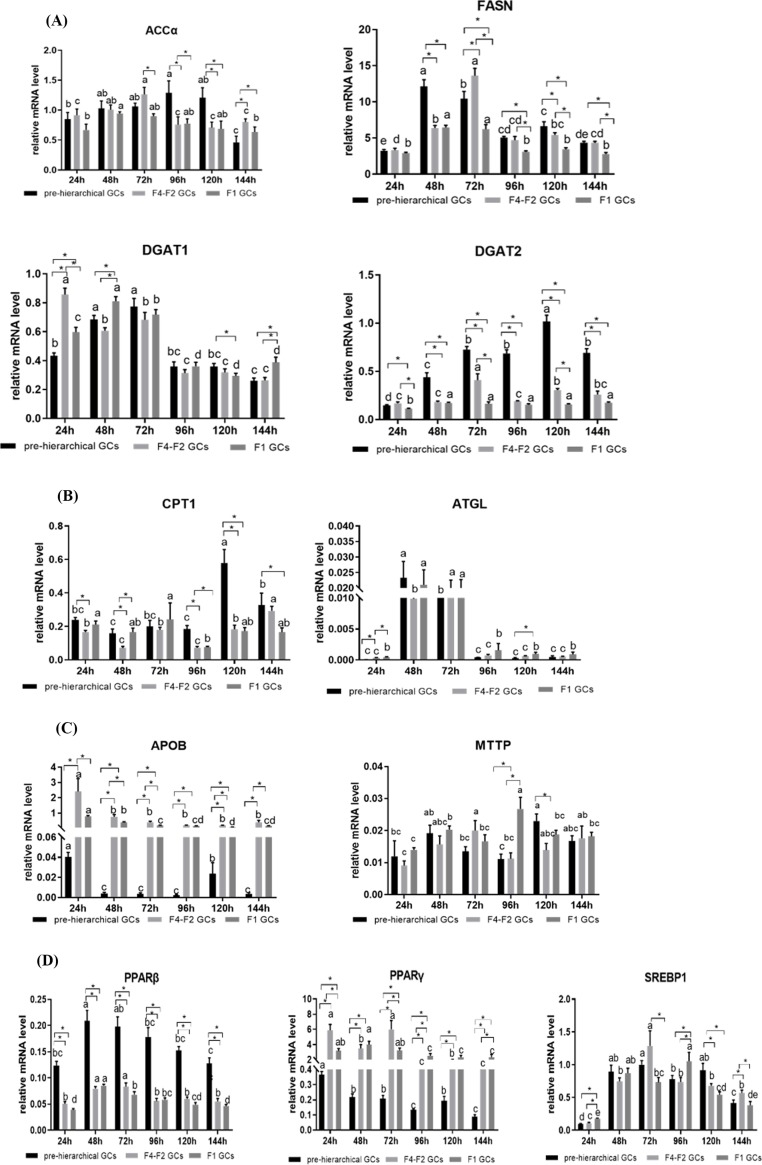

Expression profiles of lipid metabolism-related marker genes in cultured GCs of geese follicles at different developmental stages

The mRNA levels of lipid metabolism-related marker genes were assessed by qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 3A, lipogenic genes including acetyl-CoA carboxylase (accα), fatty acid synthase (fasn), diglyceride acyltransferase 1 (dgat1) and diglyceride acyltransferase 2 (dgat2) were expressed in all GCs but presented different expression patterns among three cohorts of GCs during in vitro culture period. While the mRNA levels of accα showed a significant increase in the pre-hierarchical GCs from 96 h to 120 h compared with hierarchical GCs (P < 0.05). The mRNA expression of fasn in the pre-hierarchical GCs was higher than that of the hierarchical GCs. The mRNA levels of dgat1 showed a trend of increasing early and decreasing later throughout the incubation period. As for dgat2, its mRNA levels were higher in pre-hierarchical than in hierarchical GCs (P < 0.05), but there was no significant difference in its expression between the F1 and F4-F2 GCs (P > 0.05).

Figure 3. Expression patterns of genes involved in lipid metabolism in vitro culture GCs.

(A) Genes of lipogenic enzymes; (B) genes of lipolytic enzymes; (C) genes of lipid transport; (D) genes of transcription factors. Bars with different lowercase letters are significantly different for the same type of cell during the cultured time in vitro (P < 0.05). * indicates significant differences among GCs of three different stages in the same cultured time (P < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 replicate tanks). mRNA levels were normalized by β-actin and 18s.

As shown in Figure 3B, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1(cpt1), one of FAO-related genes, showed that a tendency of the levels of mRNA were higher in pre-hierarchical GCs than the hierarchical GCs. Adipose triglyceride lipase (atgl), lipolysis-related genes, the mRNA level was highest at 48 and 72 h. As for lipid transport, we measured the mRNA levels of apolipoprotein B(apob) and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (mttp). Levels of apob were higher in hierarchical than in pre-hierarchical GCs (P > 0.05). The mRNA levels of mttp showed no significant changes. Additionally, we also measured the mRNA levels of transcriptional factors involved in the regulation of lipid metabolism including sterol-regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). Levels of srebp1 increased with the increase of culture time, and then decreased (Figure 3D). The mRNA levels of pparβ had higher expression in pre-hierarchical GCs than hierarchical (P > 0.05). As for pparγ, the expression was highest in F4-F2 GCs.

Discussion

In the present study, we primarily revealed the characteristics of lipid metabolism in cultured GCs from geese follicles at different developmental stages. During the entire incubation period, lipid deposition occurred in all three cohorts of GCs (Figure 1). With the extension of incubation time, the amount of lipids accumulated in these GCs increased gradually, reached the maxima after 96 h of culture, and then decreased (Figure 2). The morphology of lipid droplets (LDs) varied among these three cohorts, especially between pre- and hierarchical GCs. The pre-hierarchical GCs preferred to form smaller LDs that were generally spherical in shape. By contrast, both the F4-F2 and F1 GCs tended to form relatively larger LDs that were shown as spherical or irregular. Meanwhile, after Oil red O staining, the color of LDs was generally brighter in the F1 GCs compared with the other two cohorts (Figure 1). LDs are highly dynamic organelles, and they can store neutral lipids and are involved in many physiological processes [40–42]. The follicles of almost all mammals contain LDs, and LDs are considered to be a source of energy for oocyte maturation [43,44]. As ovarian follicles grow, it was reported that changes in both the size and number of LDs changed [43,45,46]. The total intracellular lipid content increased gradually with the follicular growth, and increased exponentially in large antral follicles [26,47]. Our study showed that the lipid content in GCs increased with the follicle development, which was similar to these reports. Since both secretion of steroid hormones and energy metabolism increased with the development of follicles, it was postulated that differences in the amount of lipids deposited in different cohort of GCs could be dependent on the stage of follicle development. And this may reflect the different capacities of the GCs to respond to hormonal signals and provide energy for follicle development. Our results showed that the lipid content of GCs increased with the development of goose follicles, and the morphology of LDs was related to the stage of follicular development.

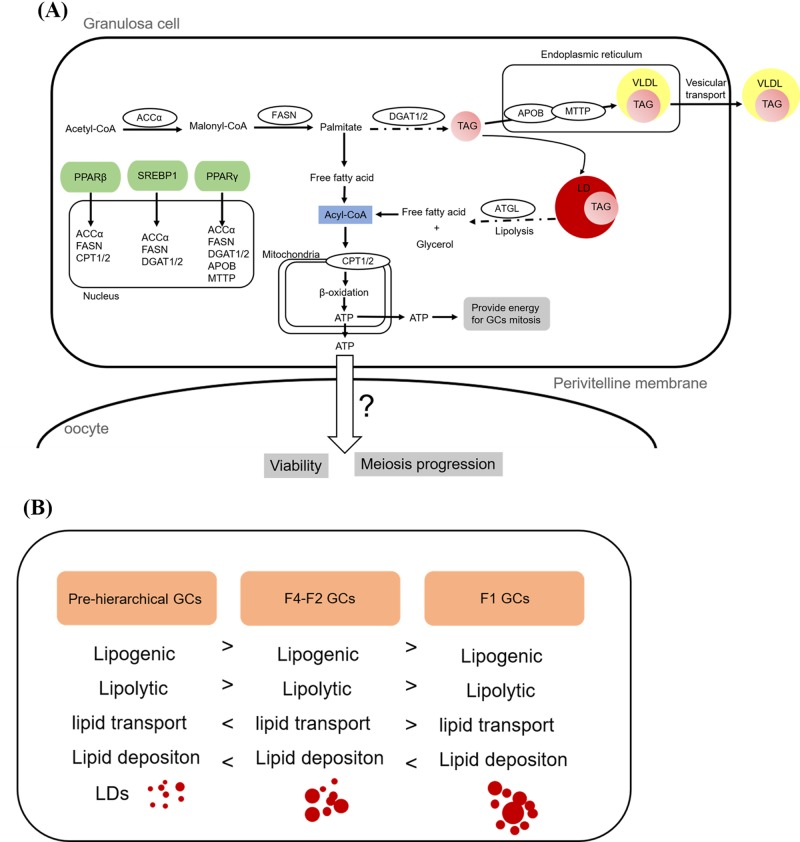

To further explore the lipid metabolism characteristics among the three cohorts of GCs, 11 genes associated with lipid metabolism were selected for qRT-PCR. Among them, accα, fasn and dgat1/2 were recognized as key enzymes in de novo synthesis of fatty acids and triglyceride synthesis, respectively [48–52]. Our results showed that the mRNA levels of accα and fasn were significantly higher in pre-hierarchical GCs than in the other two cohort cells in 96 and 120 h. And the mRNA levels of dgat2 were also significantly higher in pre-hierarchical GCs than the other two cohort cells. At the same time, the mRNA expression pattern of pparβ was similar to that of dgat2. These results showed that pre-hierarchical GCs may synthesize more endogenous triglycerides than hierarchical GCs. The apob and mttp co-regulate of lipoprotein assembly and secret [53,54]. In our study, the mRNA levels of apob were higher in hierarchical GCs than pre-hierarchical GCs, and the mRNA levels of mttp showed no significantly changed among the three cohorts of GCs. pparγ is the lipid metabolism-related key transcriptional factor [55], and pparγ can regulate GCs steroidogenesis by influence aromatase activity [24] and loss of pparγ leads to reduce fertility [56]. The present study indicated that the mRNA levels of pparγ first increased and then decreased with follicular development that was consistent with previous studies [57,58]. Studies in mammals have shown that dgat2 is related to the size of lipid droplets. When overexpressing dgat2, a large number of large lipid droplets are produced. [59]. Contrary to our study, in our study, the expression level of dgat2 was higher in pre-hierarchical GCs than in hierarchical GCs, but the size of lipid droplets in hierarchical GCs was smaller than pre-hierarchical GCs. In addition, we know that phenotypic indicators are determined by multiple factors. Lipid deposition is determined by lipid synthesis rate, lipolysis rate and lipid transport rate. In our study, lipid deposition of hierarchical GCs is higher than that pre-hierarchical GCs. Why is this happening? It is not possible to explain the problem simply by quantification of several genes, but we can speculate that the expression of lipogenic genes in pre-hierarchical GCs is higher than in hierarchical GCs. But at the same time, the expression level of the lipolysis genes was also high (Figure 4A). Pre-hierarchical GCs mitosis are prevalent, so they require a lot of energy to supply their own metabolism. Put together, the lipid deposition of the pre-hierarchical GCs is less than the hierarchical GCs (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Schematic representation of the mechanisms possibly responsible for developmental stage-dependent changes in the capacity of lipid accumulation in GCs.

(A) Putative roles of lipid metabolism-related genes in goose GCs. (B) Differential expression profiles of genes related to lipogenesis, lipolysis, lipid transport, and lipid deposition lead to differences in the capacity of lipid accumulation in GCs of follicles at different developmental stages.

In summary, these differences in expression of lipid metabolism-related genes and lipid content may be related to the stage of follicular development and reflect the function difference of GCs at different follicular development stages.

Abbreviations

- GC

granulosa cell

- LD

lipid droplet

- TAG

triglycerides

- VLDL

very-low density lipoprotein

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 31672424]; China Agricultural Research System [grant number CARS-42-4]; and Project of National Science and Technology Plan for the Rural Development in China [grant number 2015BAD03B06].

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: Shenqiang Hu and Xiang Gan; Data analysis: Shanyan Gao; Funding acquisition: Jiwen Wang; Investigation: Shanyan Gao, Xiang Gan, Hua He, Yan Deng, Xi Chen, and Li Li. Methodology: Shanyan Gao; Project administration: Jiwen Wang, Liang Li and Jiwei Hu; Supervision: Jiwen Wang; Visualization: Shanyan Gao; Writing (original draft): Shanyan Gao; Writing (review and editing): Shanyan Gao and Shenqiang Hu.

References

- 1.Johnson A.L. (2014) The avian ovary and follicle development: some comparative and practical insights. Turkish J. Veterinary and Animal Sci. 38, 660–669 10.3906/vet-1405-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palma G.A. et al. (2012) Biology and biotechnology of follicle development. Sci. World J. 2012, 938138 10.1100/2012/938138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braw-Tal R. (2002) The initiation of follicle growth: the oocyte or the somatic cells? Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 187, 11–18 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00699-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilchrist R.B., Ritter L.J. and Armstrong D.T. (2004) Oocyte-somatic cell interactions during follicle development in mammals. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 82, 431–446 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orisaka M. et al. (2010) Effects of ovarian theca cells on granulosa cell differentiation during gonadotropin-independent follicular growth in cattle. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 73, 737–744 10.1002/mrd.20246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter T.E. et al. (1989) Differential steroid production between theca interna and theca externa cells: a three-cell model for follicular steroidogenesis in avian species. Endocrinology 125, 109 10.1210/endo-125-1-109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manabe N. et al. (2002) Regulatory Mechanisms of Granulosa Cell Apoptosis in Ovarian Follicle Atresia. Reproduct. Biol. Update Kyoto 343–347 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manchanda R., Kim J.M. and Tsang B.K. (2001) Role of prostaglandins in the suppression of apoptosis in hen granulosa cells by transforming growth factor alpha. Reproduction 122, 91 10.1530/rep.0.1220091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elis S. et al. (2015) Cell proliferation and progesterone synthesis depend on lipid metabolism in bovine granulosa cells. Theriogenology 83, 840–853 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2014.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell B.K. et al. (2010) The effect of monosaccharide sugars and pyruvate on the differentiation and metabolism of sheep granulosa cells in vitro. Reproduction 140, 541–550 10.1530/REP-10-0146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu W. (2011) Expression and regulation of adipocyte fatty acid binding protein in granulosa cells and its relation with clinical characteristics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrine 40, 196–202 10.1007/s12020-011-9495-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svetlana U. et al. (2015) MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Lipids and Gene Expression Reveals Differences in Fatty Acid Metabolism between Follicular Compartments in Porcine Ovaries. Biology 4, 216–236 10.3390/biology4010216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vireque A.A. et al. (2017) MALDI mass spectrometry reveals that cumulus cells modulate the lipid profile of in vitro-matured bovine oocytes. Syst. Biol. Reproduct. Med. 63, 86–99 10.1080/19396368.2017.1289279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haggarty P. et al. (2006) Fatty acid metabolism in human preimplantation embryos. Hum. Reprod. 21, 766–773 10.1093/humrep/dei385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira C.R. et al. (2010) Single embryo and oocyte lipid fingerprinting by mass spectrometry. J. Lipid Res. 51, 1218 10.1194/jlr.D001768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira C.R. et al. (2015) Ambient ionisation mass spectrometry for lipid profiling and structural analysis of mammalian oocytes, preimplantation embryos and stem cells. Reproduct. Fert. Dev. 27, 621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suttonmcdowall M.L., Gilchrist R.B. and Thompson J.G. (2010) The pivotal role of glucose metabolism in determining oocyte developmental competence. Reproduction 139, 685–695 10.1530/REP-09-0345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris S.E. et al. (2010) Pyruvate and oxygen consumption throughout the growth and development of murine oocytes. Mol. Reproduct. Dev. 76, 231–238 10.1002/mrd.20945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leese H.J. and Barton A.M. (1984) Pyruvate and glucose uptake by mouse ova and preimplantation embryos. J. Reprod. Fertil. 72, 9–13 10.1530/jrf.0.0720009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laura S.L. et al. (2014) Fatty acid synthesis and oxidation in cumulus cells support oocyte maturation in bovine. Mol. Endocrinol. 28, 1502–1521 10.1210/me.2014-1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paczkowski M., Schoolcraft W.B. and Krisher R.L. (2014) Fatty acid metabolism during maturation affects glucose uptake and is essential to oocyte competence. Reproduction 148, 429–439 10.1530/REP-14-0015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yenuganti V.R., Viergutz T. and Vanselow J. (2016) Oleic acid induces specific alterations in the morphology, gene expression and steroid hormone production of cultured bovine granulosa cells. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 232, 134–144 10.1016/j.ygcen.2016.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Froment P. et al. (2003) Expression and functional role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in ovarian folliculogenesis in the sheep. Biol. Reprod. 69, 1665–1674 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrama I. and Singh D. (2015) Direct action of natural and synthetic Pparγ ligands on buffalo granulosa cell proliferation and steroidogenesis. Buffalo Bulletin 34, 401–415 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komar C.M. and Curry T.E. Jr (2003) Inverse Relationship Between the Expression of Messenger Ribonucleic Acid for Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ and P450 Side Chain Cleavage in the Rat Ovary1. Biol. Reprod. 69, 549 10.1095/biolreprod.102.012831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma R.K., Vats R. and Sawhney A.K. (1996) Changes in follicular lipids during follicular growth in the goat (Capra hircus) ovary. Small Ruminant Res. 20, 177–180 10.1016/0921-4488(95)00793-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva R.C. et al. (2011) Ultrastructural characterization of porcine oocytes and adjacent follicular cells during follicle development: lipid component evolution. Theriogenology 76, 1647–1657 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjersing L. (1967) On the ultrastructure of follicles and isolated follicular granulosa cells of porcine ovary. Z. Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 82, 173–186 10.1007/BF01901700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fair T. et al. (1997) Oocyte ultrastructure in bovine primordial to early tertiary follicles. Anat. Embryol. 195, 327–336 10.1007/s004290050052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen R. et al. (2018) Evidence for the existence of de novo lipogenesis in goose granulosa cells. Poult. Sci. pey400–pey400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia D. et al. (2014) Histological and developmental study of prehierarchical follicles in geese. Folia. Biol. 62, 171–177 10.3409/fb62_3.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert A.B. et al. (1980) Cellular changes in the granulosa layer of the maturing ovarian follicle of the domestic fowl. Br. Poult. Sci. 21, 7 10.1080/00071668008416667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson A.L. (2015) Ovarian follicle selection and granulosa cell differentiation. Poult. Sci. 94, 781 10.3382/ps/peu008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tilly J.L., Kowalski K.I. and Johnson A.L. (1991) Stage of ovarian follicular development associated with the initiation of steroidogenic competence in avian granulosa cells. Biol. Reprod. 44, 305–314 10.1095/biolreprod44.2.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng Y. et al. (2018) Comparison of growth characteristics of in vitro cultured granulosa cells from geese follicles at different developmental stages. Biosci. Rep. 38, BSR20171361 10.1042/BSR20171361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen X. et al. (1993) Chicken oocyte growth: receptor-mediated yolk deposition. Cell Tissue Res. 272, 459–471 10.1007/BF00318552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbert A.B. et al. (1977) A method for separating the granulosa cells, the basal lamina and the theca of the preovulatory ovarian follicle of the domestic fowl (Gallus domesticus). J. Reprod. Fertil. 50, 179–181 10.1530/jrf.0.0500179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yagi K. et al. (2004) A novel preadipocyte cell line established from mouse adult mature adipocytes. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 321, 967–974 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Livak K.J. and Schmittgen T.D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using rea l-time quantitative PCR a nd the 2 - ct method. Method 25, 402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walther T.C. and Farese R.V. Jr (2009) The life of lipid droplets. BBA - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1791, 459–466 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thiam A.R. and Beller M. (2017) The why, when and how of lipid droplet diversity. J. Cell Sci. 130, jcs.192021 10.1242/jcs.192021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Onal G. et al. (2017) Lipid Droplets in Health and Disease. Lipids Health Dis. 16, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silva R.C. et al. (2011) Ultrastructural characterization of porcine oocytes and adjacent follicular cells during follicle development: lipid component evolution. Theriogenology 76, 1647–1657 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sturmey R.G., O’Toole P.J. and Leese H.J. (2006) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis of mitochondrial:lipid association in the porcine oocyte. Reproduction 132, 829–837 10.1530/REP-06-0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dadarwal D. et al. (2015) Organelle reorganization in bovine oocytes during dominant follicle growth and regression. Reproduct. Biol. Endocrinol. Rb & E 13, 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paulini F. et al. (2014) Ultrastructural changes in oocytes during folliculogenesis in domestic mammals. J. Ovarian Res. 7, 102 10.1186/s13048-014-0102-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sangha G.K. and Guraya S.S. (1989) Biochemical changes in lipids during follicular growth and corpora lutea formation and regression in rat ovary. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 27, 998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cases S. et al. (2001) Cloning of DGAT2, a Second Mammalian Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase, and Related Family Members. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38870–38876 10.1074/jbc.M106219200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y. et al. (2004) The Human Fatty Acid Synthase Gene and De Novo Lipogenesis Are Coordinately Regulated in Human Adipose Tissue. J. Nutr. 134, 1032–1038 10.1093/jn/134.5.1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ntambi J.M. (2010) Genetic control of lipogenesis: role in diet-induced obesity. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 45, 199 10.3109/10409231003667500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y. et al. (2004) The human fatty acid synthase gene and de novo lipogenesis are coordinately regulated in human adipose tissue. J. Nutr. 134, 1032–1038 10.1093/jn/134.5.1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yen C.L.E. et al. (2008) DGAT enzymes and triacylglycerol biosynthesis. J. Lipid Res. 49, 2283 10.1194/jlr.R800018-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hussain M.M., Shi J. and Dreizen P. (2003) Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and its role in apob-lipoprotein assembly. J. Lipid Res. 44, 22 10.1194/jlr.R200014-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borén J., Rustaeus S. and Olofsson S.O. (1994) Studies on the assembly of apolipoprotein B-100- and B-48-containing very low density lipoproteins in McA-RH7777 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 25879–25888 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spiegelman B.M. and Flier J.S. (2001) Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell 104, 531–543 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00240-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yongzhi C. et al. (2002) Loss of the peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) does not affect mammary development and propensity for tumor formation but leads to reduced fertility. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17830 10.1074/jbc.M200186200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Komar C.M. et al. (2001) Expression and Localization of PPARs in the Rat Ovary During Follicular Development and the Periovulatory Period. Endocrinology 142, 4831 10.1210/endo.142.11.8429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Froment P. et al. (2003) Expression and functional role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in ovarian folliculogenesis in the sheep. Biol. Reprod. 69, 1665–1674 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stone S.J. et al. (2004) Lipopenia and skin barrier abnormalities in DGAT2-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11767–11776 10.1074/jbc.M311000200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]