Abstract

Background and Aims: In cancer patients, a common complication during chemotherapy is chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). For this reason, we decided to conduct a phase II prospective study on 33 patients with multiple myeloma at first diagnosis, to evaluate whether a nutraceutical compound given for 6 months during bortezomib (BTZ) treatment succeeded in preventing the onset of neurotoxicity. Methods: Neurological evaluation, electroneurography, and functional and quality of life (QoL) scales were performed at baseline and after 6 months. We administered a tablet containing docosahexaenoic acid 400 mg, α-lipoic acid 600 mg, vitamin C 60 mg, and vitamin E 10 mg bid for 6 months. Results: Concerning the 25 patients who completed the study, at 6-month follow-up, 10 patients had no neurotoxicity (NCI-CTCAE [National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events] = 0), while 13 progressed to NCI-CTCAE grade 1, 1 had NCI-CTCAE grade 1 with pain, and 1 experienced a NCI-CTCAE grade 2. Painful symptoms were reported only in 2 patients, and we observed stability on functional and QoL scales in all patients. None of the 25 patients stopped chemotherapy due to neurotoxicity. Conclusions: Our data seem to indicate that the co-administration of a neuroprotective agent during BTZ treatment can prevent the appearance/worsening of symptoms related to CIPN, avoiding the interruption of BTZ and maintaining valuable functional autonomy to allow normal daily activities. We believe that prevention remains the mainstay to preserve QoL in this particular patient population, and that future studies with a larger patient population are needed.

Keywords: nutraceutical compound, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, multiple myeloma, bortezomib, prevention, QoL

Introduction

Patients with multiple myeloma (MM) can present peripheral neuropathy (PN) as a frequent disease-related clinical manifestation or as a therapy-related complication induced by oncological treatment.1-3 Mild axonal sensory-motor neuropathy is the most usual type of PN,3 but a demyelinating PN is also possible to observe.4 Data about incidence of PN in MM patients are not clear and contrasting data have been published in clinical studies, reporting that about 20% of patients suffer from disease-related PN at diagnosis and up to 75% may experience chemotherapy-induced PN (CIPN).3,6-8

There have been studies about the mechanism responsible for CIPN in MM, depending on chemotherapy (CT) used. For example, among the old CTs, vincristine interferes with microtubule-aided post-axonal transport, while cisplatin, through DNA damage and inhibition of protein synthesis, induces apoptosis of the dorsal root ganglion.8,9 On the other hand, the novel immunomodulator agents (ie, thalidomide, lenalidomide) and proteasome inhibitors (ie, bortezomib [BTZ]) exert a pleiotropic action on nerve fibers, although the exact mechanism responsible for neurologic damage is still not clear.10 Regarding thalidomide-related neurotoxicity, some data highlight that one of the most important mechanisms includes capillary damage and secondary anoxemia in nerve fibers, but also an accelerated neuronal-cell death by downregulation of tumor necrosis factor-α and the consequent inhibition of nuclear factor κβ.11 The neurotoxicity due to BTZ seems related to transient release of intracellular calcium stores with consequent mitochondrial calcium influx and caspase-mediated apoptosis12,13 as well as to altered intracellular calcium homeostasis that can induce pain and paresthesia.13

CIPN is usually dose-dependent and heavily affects patients’ quality of life (QoL), inducing disabilities, even worsening preexisting polyneuropathy1,14,15 so intensely as to become one of the most important factors leading to dose reduction or discontinuation of CT.1,16 In patients with CIPN the most common symptom is pain, which often becomes unbearable to the point that patients need to stop CT and/or activities of everyday life are impossible to be performed.15 Among the newer CT medications for the treatment of hematooncological diseases, BTZ is the first-line proteasome inhibitor drug in the treatment of MM.17 BTZ may induce CIPN that is characterized by a reversible painful distal neuropathy that improves or disappears 3 to 4 months after treatment discontinuation.1 This CIPN neuropathy can occur in 33% of newly diagnosed MM patients as grade 1 or 2, according to the National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE),18 and as grade 3 or 4 in 18% of newly diagnosed patients.15 In recent years, the route of administration of BTZ has progressively moved from intravenous to subcutaneous, given that the latter has a better profile of toxicity, precisely regarding the onset and severity of PN; therefore, it results in a better treatment tolerability and improved compliance.19 Nevertheless, CIPN is still one of the most relevant dose-limiting toxicities related to BTZ treatment.20,21 No method of CIPN prevention was suggested by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, although their guidelines reported therapies aimed at reducing CIPN.22,23 There are some evidence only for treatment of CIPN pain that support moderate recommendation of antidepressant duloxetine.22 In fact, Smith and colleagues24 reported that duloxetine administration produced a low 1.06 point reduction in pain on a 10-point scale from baseline, but was also associated with adverse events (AE) such as fatigue and nausea.

To date there are some preliminary studies that show the positive effect of using several agents for treatment of oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy, even though those treatments require further investigations: glutathione, carbamazepine, gabapentin, amifostine, acetyl-L-carnitine, α-lipoic acid (ALA), Gingko biloba extract, and celecoxib.25,26 To our knowledge, there are only 2 available studies regarding the treatment of BTZ-induced PN in MM patients: the first randomized trial by Zhang et al27 shows that mecobalamin administration in these patients leads to a reduction of PN in the 77.7%. Differently in the study of Callender et al,28 the addition of acetyl-carnitine for prophylactic purposes leads to a minor appearance of grade 3 CIPN in the treated group compared with the control group.

Literature data indicate that to reduce inflammation and to favor the formation of new axons and intersynaptic connections, nutraceutical compounds with antioxidant and axonal regrowth action may be useful.29 Among the newly marketed nutraceuticals, some compounds that contain docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and ALA exert powerful neurotrophic, neuroprotective, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory actions, due to the simultaneous presence of both these molecules.29 To date, there are data demonstrating the efficacy of these compounds in the treatment of PN in diabetic patients.30-34

Even when concomitant pathologies are present, DHA and ALA demonstrated high tolerability, with no side effects to gastrointestinal and renal systems, and extreme safety, so there is the possibility to use them in young and old patients.35-38 They can be given in association with steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pain relief medications, and gabaergic drugs.29 Based on these evidences, we conducted a Phase II prospective study on 33 patients with MM at first diagnosis aiming to evaluate if using a nutraceutical compound with DHA and ALA during the first 6 months of BTZ treatment would prevent the onset of neurotoxicity.

Methods

The primary objective of the study was to assess if the use of a nutraceutical compound with DHA and ALA could prevent the onset of chemo-induced peripheral neurotoxicity of grade II according to NCI-CTCAE.18 We used as the primary efficacy variable a cutoff represented by grade II of neurotoxicity on the NCI-CTCAE because guidelines recommended BTZ withdrawal and discontinuation when PN reaches grades 3 and 4 of NCI-CTCAE.39

Secondary objectives were to verify if the onset of painful symptoms of PN could be prevented by the nutraceutical, or the nutraceutical could maintain stability of QoL and functional autonomy.

Subjects

We consecutively enrolled in the study patients with newly diagnosed MM, diagnosed according to the International Myeloma Working Group Criteria,40 followed by the Hematology Unit of our institute, undergoing subcutaneous administration of BTZ. Patients were managed according to the current standard of care and no additional diagnostic or therapeutic procedure was performed. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by Regina Elena National Cancer Institute’s Ethics Committee (RS661/15-RS571/15-1629).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18 to 75 years; newly diagnosed MM; written informed consent; absence of neurotoxicity demonstrated by grade 0 of NCI-CTCAE; absence of painful symptoms demonstrated by grade 0 of VAS (Visual Analogue Scale).

Patients with other PN (eg, diabetic polyneuropathy), with other hematologic malignancies, previously treated or with previous neurological or psychiatric disorders were excluded from this analysis. Patients with severe vitamin deficiency or documented drug or alcohol addiction were also excluded.

Study Treatment

The study treatment (Neuronorm) is composed of DHA (400 mg), ALA (600 mg), vitamin C (60 mg), and vitamin E (10 mg). It is a nutritional supplement containing DHA, ALA, synthetic vitamin C, and vegetable vitamin E. Trophic and antioxidant properties of these constituents that act on the nervous system were supported by literature in experimental or animal studies.30,31,33,37,41 The presence of both vitamins C and E in this compound has 2 reasons. First, DHA, being the fatty acid with the highest number of double bonds, is extremely exposed to oxidation risk; for this reason, it is very important to preserve it with the presence of vitamins C and E (as well as ALA). Second, vitamin C is needed as a cofactor of dopamine β-monooxygenase for the biosynthesis of noradrenaline (and adrenaline); the EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) Panel concludes that a cause and effect relationship has been established between the dietary intake of vitamin C and normal function of the nervous system.42,43 Vitamin E possesses neuroprotective properties; therefore, its deficiency is linked to PN.43,44

Inpha Duemila srl unconditionally and freely supplied the investigational product, and it was dispensed to the patients at the study site (Inpha Duemila srl; via Cardinale Ferrari, 6 Mariano Comense [CO], Italy; made in via Ariosto, 50/60 Trezzano sul Naviglio [MI], Italy; licensed by Ambros Pharma via Larga 2 Milano, Italy). The manufacturer is SIIT, via Canova, 7-20090, Trezzano sul Naviglio (Milano). Each used dose came from the same lot number, subject to a standardized quality control.

The study treatment was then taken orally, 1 tablet twice daily for 6 months, and patients received pill bottles at each neurological visit, every month. Patients’ compliance was verified by checking the number of pills returned.

The patients were treated with 3 different chemotherapeutic protocols including subcutaneous BTZ at a dose of 1.3 mg/m2: (1) BTZ with thalidomide and dexamethasone (VTD), with a median of 4 cycles (range = 3-5) administered every 21 days using a twice weekly schedule of BTZ; (2) 5 cycles of BTZ with melphalan and prednisone (VMP) every 35 days with biweekly subcutaneous BTZ; and (3) VMP cycles “attenuated” (5 cycles) using a 1-week schedule of BTZ established “a priori,” considering age and comorbidity.

Visits Schedule

The following assessments were performed at baseline and final follow-up at 6 months: neurological examination, electroneurography (ENG), and evaluation scales: NCI-CTCAE,18 reduced version of Total Neuropathic Score45,46 (TNSr), VAS47 for pain, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life-Questionnaire-Core-3048 (EORTC QLQ-C30), European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-CIPN 20-item scale49 (QLQ-CIPN20), and Daily and Instrumental Life Activities scale50 (ADL/IADL). At baseline, blood levels of vitamin B12 were measured, and after eligibility assessment, Neuronorm was given to patients. Every month, patients received neurological examination to monitor the occurrence of any AE.

Assessments

Primary efficacy variable was to maintain a neurotoxicity less than grade 2 under the NCI-CTCAE system and grade 10 of TNSr system at final follow-up.

Secondary efficacy variable was to maintain a stability in all other scales compared with baseline at final follow-up.

To assess tolerability, the incidence of AEs during treatment with BTZ and Neuronorm was assessed using the NCI-CTCAE.18

Any unexpected medical problem (sign, symptom, or disease) that happens during the assumption of a specific drug, that may or may not be considered related to the drug, is considered an “AE”. The analysis of toxicity was performed including all the patients who assumed at least one dose of drug. To gain the best recognition of AE, each unexpected medical problem, spontaneously reported or observed, was recorded relating to details of time of onset and resolution, intensity, need for eventual concomitant treatment, and with the investigator’s opinion of a possible relationship with study treatment.

Assessment Tools/Scales

Neurological examination included a medical history specifically addressing symptoms of numbness, tingling or pain, weakness in the extremities, in addition to a complete neurological examination focused on tendon reflexes, strength and sensory modalities, assessed with Rydel Seiffer tuning fork.51

Electroneurography

Nerve conduction was examined using conventional procedures and a standard electromyography machine (Medelec Synergy). We chose the right median and peroneal nerves to examine motor nerves and the right median and bilateral sural nerves to examine sensory nerves. Compound muscle action potentials were recorded from the abductor pollicis brevis, and sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) were recorded from the second digit. Skin temperature was measured near the stimulation site and maintained above 32.0°C. Median SNAPs were recorded from the index finger after antidromic stimulation at the wrist, and sural SNAPs were noted at lateral malleolus after antidromic stimulation delivered 14 cm proximally at mid-calf.2

Evaluation Scales

NCI-CTCAE is an oncology toxicity scale that grades the sensory and motor peripheral neurotoxicity CIPN based on severity of symptoms and disability from grades 1 (mild) to 4 (disabling).11,52

TNSr is a composite score to evaluate peripheral nerve impairment, ranging between 0 and 32 points. This score sums up motor, sensory, and autonomic symptoms and signs; quantitative determination of the vibration perception threshold; and neurophysiological examination of 1 motor and 1 sensory nerve in the leg. For this study, to calculate TNRs, we decided to use the amplitude values of peroneal and sural nerve. Using this score the severity of the neuropathy can be classified as mild (1-10), moderate (11-20), and severe (>20).45,46

EORTC QLQ-C30 Scale is a self-assessed questionnaire used in cancer patients for the evaluation of functional status, symptoms, and QoL, ranging between 0 and 100 points (a higher scale score represents higher response level or higher level of symptoms).48

EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 Scale is a self-assessed questionnaire used in cancer patients for the evaluation of sensory symptoms, motor and autonomic peripheral neuropathies induced by CT, ranging between 0 and 100 points (a higher scale score represents more symptoms/problems).49

The VAS is a self-assessed scale for pain ranging between 0 (no pain) and 10 (unbearable pain).47

The ADL/IADL questionnaires50 are specific tools for the evaluation of basic and instrumental daily life activities for the assessment of functional autonomy. ADL ranges between 0 and 6, and IADL ranges between 0 and 8, where 0 indicates full dependency and the highest score indicates independence in all functions.

Statistical Analysis

This trial is to be considered exploratory, in order to get information on the possible effect of the nutraceutical. The obtained results will be used to design a double-blinded placebo-controlled study with the appropriate sample size.

The incidence of patients with grade 2 (or higher) of neurotoxicity with the NCI-CTCAE scales at the 6-month follow-up was considered the primary endpoint. We designed the study as a single stage, as proposed by A’Hern.53 According to literature data, a mean incidence rate of 40%12,21 was taken as the null hypothesis (p0, ie, an incidence of toxicity that, if true, will imply that the proposed treatment could not be considered adequate). As an alternate hypothesis, an incidence rate of 20% was taken (ie, an incidence that, if true, will imply that our treatment had an acceptable toxicity control). Assuming a level of significance of 5% and a power of 80%, 33 patients were enrolled in the study. We considered that if at least 25 patients did not experience neurotoxicity of grade 2 NCI-CTCAE or higher, the treatment would be considered adequate to control neurotoxicity and may be proposed for a subsequent, larger comparative study.

Primary and secondary results were reported with their 95% confidence interval.

Patients’ characteristics and treatments were described by mean, standard deviation, and range if related to quantitative variables and absolute frequencies relative to qualitative variables.

The incidence of patients with grade 2 (or higher) neurotoxicity at follow-up was estimated as the ratio between the number of patients with grade 2 (or higher) toxicity and the number of enrolled patients.

The changes between baseline and follow-up in TNSr, mean VAS score for pain, EORTC QLQ-C30, and EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 were analyzed using repeated measure t test.

Results

Of 33 patients, 6 dropped out (because of disease progression or a change in chemotherapeutic regimen) and 2 were immediately lost to follow-up. Twenty-five patients completed the study (6 months; see Table 1). Regarding the CT schedule with BTZ, 17 patients received VTD, administered every 21 days using a twice weekly schedule of BTZ (median cycles = 4, range = 3-5), 9 patients received 5 cycles of VMP every 35 days with biweekly subcutaneous BTZ, whereas the remaining 7 patients were treated with 5 VMP cycles using a 1-week schedule of BTZ. Regarding the study treatment with Neuronorm, all patients returned the individually assigned bottles empty.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical and Biologic Features of Entire Population (n = 33).

| Parameters | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 17 (51) |

| Mean age, years | 65.3 (8.8) |

| Diagnosis | |

| IgG kappa | 19 (57) |

| IgG lambda | 3 (9) |

| IgA kappa | 5 (15) |

| IgD kappa | 1 (3) |

| Non-secretory myeloma | 1 (3) |

| Micromolecular kappa | 2 (6) |

| Micromolecular lambda | 1 (3) |

| Oligosecretory kappa | 1 (3) |

| ISS stage | |

| 1 | 17 (51) |

| 2 | 6 (18) |

| 3 | 10 (30) |

| Durie and Salmon stage | |

| IA | 10 (30) |

| IIA | 14 (42) |

| IIIA | 5 (15) |

| II-IIIB | 4 (12) |

| Cytogenetic analysis53 | |

| Intermediate-high risk | 10 (30) |

| Standard risk | 17 (51) |

| Negative | 1 (3) |

| NA | 5 (15) |

| Treatment | |

| VTDa | 17 (51) |

| VMP with biweekly BTZ administration | 9 (27) |

| VMP with weekly BTZ administration | 7 (21) |

| Response assessment39 | |

| CR | 15 (45) |

| VGPR | 9 (27) |

| PR | 4 (12) |

| SD/PD | 4 (12) |

| NE | 1 (3) |

Abbreviations: Ig, immunoglobulin; ISS, International Staging System; NA, not available; VTD, BTZ with thalidomide and dexamethasone; VMP, BTZ with melphalan and prednisone; BTZ, bortezoimb; CR; complete response; VGPR, very good partial response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; NE, not evaluable.

In all patients treated with VTD, BTZ was administered twice weekly.

During the 6 months of observation, 28 (84%) patients experienced at least partial remission, while 4 (12%) had stable disease or disease progression (Table 1).54

At baseline, 25/33 patients have vitamin B12 levels in the normal range (mean value = 391.05 pg/mL).

All patients enrolled had NCI-CTCAE = 0 (Table 3).

Table 3.

EORTC QLQ-C30: Comparison of Mean Scores of All Evaluated Patients Between Baseline and Final Follow-up (6 Months).

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | Baseline (Mean ±SD) | Final (Mean ± SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | 78.6 ± 20.8 | 77.3 ± 17.6 | .77 |

| Role | 77.3 ± 30.9 | 76.3 ± 27.7 | .87 |

| Emotional | 82.9 ± 15.6 | 79.8 ± 24.0 | .40 |

| Cognitive | 89.0 ± 15.9 | 85.4 ± 19.1 | .32 |

| Social | 85.5 ± 22.6 | 78.6 ± 21.0 | .15 |

| Fatigue | 28.8 ± 22.5 | 33.3 ± 19.9 | .42 |

| Nausea | 3.1 ± 8.04 | 6.8 ± 15.5 | .23 |

| Pain | 22.8 ± 30.7 | 22.2 ± 23.1 | .92 |

| Dyspnea | 19.7 ± 26.6 | 18.5 ± 21.3 | .77 |

| Insomnia | 24.7 ± 28.6 | 23.4 ± 28.9 | .86 |

| Appetite | 3.7 ± 10.7 | 8.6 ± 17.5 | .21 |

| Constipation | 13.6 ± 19.1 | 13.6 ± 21.2 | .99 |

| Diarrhea | 6.2 ± 13.2 | 9.9 ± 22.3 | .26 |

| Financial | 11.1 ± 24.4 | 8.6 ± 19.8 | .57 |

| Quality of life | 67.9 ± 24.4 | 64.4 ± 20.6 | .46 |

Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life-Questionnaire-Core-30; SD, standard deviation.

Regarding the ITT (intention-to-treat) population (31 patients, mean follow-up 5.5 months), at the mean last follow-up available 12 patients had no neurotoxicity (NCI-CTCAE = 0), while 13 patients progressed to NCI-CTCAE grade 1, 1 patient had NCI-CTCAE grade 1 with pain, and 5 patients experienced a NCI-CTCAE grade 2.

Considering the primary endpoint, 5 out of 31 evaluable patients experienced a neurotoxicity of grade ≥2, so the endpoint was reached and the study can be considered positive.

Concerning the results of 25 patients who completed the study, at final follow-up 10 patients had no neurotoxicity (NCI-CTCAE = 0), while 13 patients progressed to NCI-CTCAE grade 1, 1 patient had NCI-CTCAE grade 1 with pain, and 1 patient experienced a NCI-CTCAE grade 2.

ENG values for peroneal and sural nerve amplitude at baseline and at 6-month follow-up were used to calculate TNSr for each patient (Table 2).

Table 2.

NCI-CTCAE Gradea, Peroneal and Sural Nerves Amplitude, and TNSr Scoreb at Baseline and at Final Follow-up Evaluation.

| Baseline Evaluation | Final Follow-up Evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCI-CTCAE Grade | Peroneal Nerve Amplitude, mV | Sural Nerve Amplitude, uV | TNSr Score | NCI-CTCAE Grade | Peroneal Nerve Amplitude, mV | Sural Nerve Amplitude, uV | TNSr Score | |

| 1 | 0 | 3.1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3.1 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | 0 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 4 | 1 | 5.3 | 0.88 | 6 |

| 3 | 0 | 3.6 | 8.3 | 0 | 1 | 3.6 | 8.3 | 3 |

| 4 | 0 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 4 | 0 | 3.3 | 7.8 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 2 | 1 | 3.7 | 5 | 4 |

| 6c | 0 | 7.2 | 3 | 3 | − | − | − | − |

| 7c | 0 | 9 | 2.2 | 3 | —- | − | − | − |

| 8 | 0 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 2 | 1 | 5.2 | 6.7 | 3 |

| 9 | 0 | 7.5 | 3.5 | 3 | 1 | 6.2 | 1.4 | 6 |

| 10 | 0 | 4 | 4.7 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1.5 | 7 |

| 11 | 0 | 2.4 | 5.3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 12 | 0 | 5.6 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 11.4 | 3 |

| 13d | 0 | 6.7 | 11.3 | 0 | 0 (2 months) | − | − | − |

| 14 | 0 | 7.1 | 2.7 | 4 | 1 | 4.3 | 0 | 8 |

| 15 | 0 | 6.5 | 2.2 | 3 | 0 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 2 |

| 16 | 0 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3 | 0 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3 |

| 17 | 0 | 6.9 | 4.7 | 2 | 1 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 6 |

| 18 | 0 | 3.3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2.2 | 0 | 7 |

| 19 | 0 | 3.6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 4 |

| 20 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| 21 | 0 | 0.6 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 1.6 | 0 | 8 |

| 22 | 0 | 4.7 | 2.5 | 3 | 2 | 1.4 | 0 | 9 |

| 23d | 0 | 1.1 | 0 | 7 | 2 (5 months) | − | − | − |

| 24d | 0 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 3 | 0 (1 month) | − | − | − |

| 25 | 0 | 2.9 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 9 |

| 26 | 0 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 2 | 1 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 7 |

| 27 | 0 | 4.7 | 12.5 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 7 |

| 28 | 0 | 3.1 | 20.2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6.1 | 7 |

| 29d | 0 | 6 | 4.2 | 2 | 2 (5 months) | − | − | − |

| 30 | 0 | 4.7 | 6.2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1.2 | 6 |

| 31 | 0 | 3.6 | 28.8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 19.2 | 0 |

| 32d | 0 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 5 | 2 (5 months) | − | − | − |

| 33d | 0 | 7.3 | 4.7 | 2 | 2 (3 months) | − | − | − |

Abbreviations: NCI-CTCAE, National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; TNS(r), reduced version of Total Neuropathic Score.

NCI-CTCAE: evaluated at the end of the study (6 months) for 25 patients or at last follow-up available for 6 patients.

TNS(r): range of severity of peripheral nerve impairment: mild (1-10), moderate (11-20), and severe (>20).

Immediately lost at follow-up.

Drop-out by final follow-up at 6 months, with last follow-up available.

TNSr increased from an average value of 2.6 at baseline to 4.5 at final follow-up. Although the increase was statistically significant (P = .002), the value observed at final follow-up is still within the range indicating mild neurotoxicity (1-10). No patient had moderate or severe neurotoxicity, according to TNSr.

Mean VAS score for pain increased from 0 to 1.5 between baseline and final follow-up and the increase was statistically significant (P = .006). Six patients reported a VAS score greater than 5 at the last observation, without any pain relief medications having been given to them.

The scores of the functional scales remained stable within normal limits indicating full functional autonomy throughout the follow-up period (ADL 6/6; IADL 8/8).

EORTC QLQ-C30 Functional scales mean scores remained stable and within high values between baseline and final follow-up, indicating a good level of everyday life functioning. Symptom scales mean scores remained stable and within low values between baseline and final follow-up, indicating the presence of subtle tumor-related symptoms. QoL scales mean scores remained stable and within high values between baseline and final follow-up, indicating a good QoL (see Table 3).

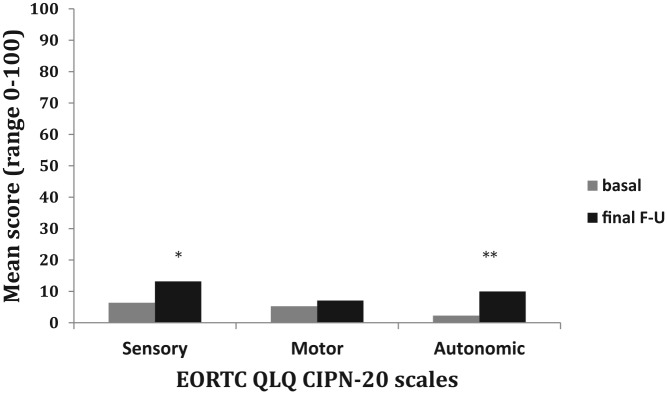

The EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 sensory scale mean scores showed a statistically significant increase of sensory symptoms between baseline and final follow-up (sensory: 6.4 ± 7.2 vs 13.2 ± 16.5; P = .05) indicating the presence of subtle CIPN-related sensory symptoms. Motor scale mean scores remained stable and within low values from baseline until final follow-up (motor: 5.3 ± 4.9 vs 7.1 ± 9.6; P = .33). Autonomic scale mean scores showed a statistically significant increase of autonomic disturbances from baseline until final follow-up (2.3 ± 7.4 vs 10.0 ± 19.4; P = .04) indicating the presence of subtle autonomic symptoms (see Figure 1).

Figure. 1.

Comparison of self-assessment questionnaire EORTC CIPN-20 mean scores between baseline and final follow-up in all patients.

*P = .05 comparison of EORTC CIPN-20 sensory scale mean scores between baseline and final follow-up.

**P = .04 comparison of EORTC CIPN-20 autonomic scale mean scores between baseline and final follow-up.

During the study period, no patient reported AEs or suspended Neuronorm treatment. Furthermore, no patient had to stop treatment with BTZ. Only 1 patient needed a 50% reduction in BTZ dosage due to hematological toxicity.

Discussion

The significant impact of CIPN on QoL in MM patients may be a relevant issue on pain intensity, leading to dose reduction or treatment discontinuation.2,10,22 For this reason we conducted a Phase II prospective study on 33 patients with MM at first diagnosis aiming to evaluate if using a nutraceutical compound with DHA and ALA (Neuronorm) during the first 6 months of BTZ treatment would prevent the onset of neurotoxicity. To consider this compound efficient, the aim was that at least 25 patients did not experience a neurotoxicity grade 2 or higher of NCI-CTCAE; since 26 of 31 evaluable patients did not experience a neurotoxicity of grade ≥2 of NCI-CTCAE at final follow-up, the endpoint is to be considered reached. It means the experimental treatment with Neuronorm would be considered adequate to control neurotoxicity.

BTZ neurotoxicity in newly diagnosed MM patients was evaluated in previous published work using different neurological assessments, not comparable to each other. Several authors have suggested a systematic neurological monitoring of patients planned to receive BTZ,46,55,56 considering the central role of BTZ in myeloma treatment55 and the paucity of data about the risk factors associated with CIPN due to BTZ. The dose-limiting toxicity of this drug is in fact peripheral neurotoxicity, reported in more than one third of the patients.54-58 which can induce a reduction or suspension of the treatment in up to about 40% of cases.55,57 Even though dose reduction could improve neurological symptoms, they can persist in some patients.59,60 Painful neuropathy can occur during BTZ therapy at a variable rate from 30% to 60%55,61 with consequent significant limitations in QoL related to neuropathic symptomatology, lasting over time.62 The aim of this study was to evaluate if using a nutraceutical compound with DHA and ALA during the first 6 months of BTZ treatment would prevent the onset of neurotoxicity.

Our patients were evaluated at baseline and after 6 months of treatment with neurological visit assessment, ENG, and administration of functional and QoL scales.

At baseline, all patients got normal results on the neurological examination and reported no neurological symptoms or pain. ADL and IADL showed the absence of any limitation in daily life activities, TNSr scores were indicative of mild neuropathy in 84% of patients, and EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 scores indicated the presence of subtle CIPN-related symptoms (sensory and autonomic) in all patients.

After 6 months of CT with BTZ (subcutaneous) in combination with Neuronorm, none of the 25 patients who completed the study stopped CT due to neurotoxicity and only 1 patient had the dose reduced by 50% due to hematological toxicity. Ten patients (40%) did not experience any neurotoxicity during the study, 14 patients (56%) had NCI-CTCAE scores for mild sensory PN (grade 1), while 1 patient (4%) reached grade 2 (moderate PN), against the 40% of patients with grade 2 expected according to the null hypothesis formulated on the basis of literature data.12,21

All TNSr scores remained within the range of mild neurotoxicity, and no patient reached the score of 10, indicating moderate neurotoxicity, although we observed a statistical increase of the average value.

Regarding painful symptomatology, no specific therapy was required, although 5 patients experienced pain during the study. Although we observed a statistical increase of average value on the mean VAS scores, the range remains between low values (0 to 1.5), which indicate low pain during follow-up.

Finally, EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 showed a significant increase in the mean score of sensory and autonomic scale, indicating the presence of a subtle polyneuropathy.

Despite this worsening, the mean score of functional ADL/IADL scales and EORTC QLQC30 questionnaire remained stable, indicating a preserved autonomy in everyday life activities, low incidence of tumor-related symptoms, and a good self-perceived QoL.

The EORTC QLQ-CIPN 20 scale is the only questionnaire we used that focuses on the patient’s subjective perception of symptoms related to CIPN. The others (ie, ADL/IADL and the EORTC QLQC30) are focused on the influence of CT-related AEs on QoL, functional and physical sphere. The EORTC QLQ-CIPN 30 allowed us to identify specific aspects related to the patient’s perception that could be undetected. These results are consistent with literature data that suggest that, for the evaluation of CIPN, the integration between instrumental and clinical evaluation of patients and self-assessment of CIPN-related symptoms questionnaire is needed.63,64 This, in fact, could allow not only to identify aspects related to the patient’s toxicity that physicians tend to underreport, but also to more accurately monitor the appearance of CIPN-related disorders.22,64

Our study completes the results of our previous published work65 that showed that the early introduction of a nutraceutical compound (Neuronorm), containing DHA and ALA, can prevent the onset or the worsening of PN and maintaining a good functional autonomy to allow normal daily activities. To date, only 2 small trials have observed an improvement of neuropathic symptoms, but using ALA alone in patients with CIPN due to docetaxel and oxaliplatin.26 Another trial failed to note any protective effect of ALA alone against CIPN.66

There is growing interest in researching new nutrient compounds that could show promise for selective neurotoxic CT agents. There are literature data about vitamin E with cisplatin,67 vitamin B6 with hexamtheylmelamin and cisplatin,68 intravenous glutathione for oxaliplatin administration,69 omega-3 fatty acids for paclitaxel,70 and acetyl-L-carnitine for paclitaxel and cisplatin that have not demonstrated clear efficacy against CIPN.23,71 However, the is need to carry out large-scale randomized-controlled trials.24,72

Our study shows some limitations: first, the small population, and second, the absence of a parallel control group.

Nevertheless, the results are suggestive of a preventive effect of Neuronorm on symptoms related to CIPN in patients with MM in the first-line treatment with BTZ. In particular, using Neuronorm for 6 months, none of the 25 patients (whether treated with VTD or VMP schedule) discontinued treatment with BTZ due to neurotoxicity, but all of them maintained a good functional autonomy and performed normal daily activities, while only 1 patient (4%) reached grade 2 NCI-CTCAE (moderate PN).These results differ from the literature data that reported discontinuation of CT in 5% to 10% of patients due to BTZ-induced PN, and incidence of Grade II CIPN in about 30% to 35% of patients.10,15,28,56-60,73-77

It is our opinion that this preventive effect of Neuronorm could be due to the synergy of its 4 active components. First of all, literature data evidenced that DHA might be useful as an adjuvant therapy for the prevention of painful neuropathy, such as diabetic neuropathy.8,78,79 Due to the fact that ALA is a co-factor of several enzymes involved in the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate and other keto acids, and in several anti-oxidant mechanisms (such as reduced gluthatione, GSH, and ascorbic acid regeneration),29 their combination represents a new approach for sustaining the subjects with neuropathy/polyneuropathy, as indicated by literature data.29 Finally, in experimental and animal studies, the last 2 components (vitamin C and vitamin E) seem to preserve DHA from oxidation risk and possess neuroprotective properties.43,44

Conclusions

Although the study involved only a small population with short follow-up, our data seem to indicate that early introduction of a neuroprotective agent in patients with newly diagnosed MM may prevent the appearance or worsening of symptoms related to PN. This will lead to preventing the interruption of the therapy with BTZ and will help the patients in keeping a functional autonomy to allow daily activities. These result seems to show that this nutraceutical may have the capability to be investigated for further trials.

Furthermore, we think that prevention remains the mainstay to preserve QoL in this particular patient population, providing a clearer and more detailed assessment for reducing CIPN risk,10,55 but only if it includes a multidisciplinary team with hematologist and neurologist working together, with periodic meetings and periodic follow-up for patients.

Moreover, our data support the need to evaluate patients with MM treated with BTZ, both with clinical measures and with specific self-report questionnaires for the detection of CIPN-related symptoms in order to identify specific aspects related to the patient’s perception of neuropathic symptomatology that otherwise could go underreported.22,64

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Marta Maschio has received support for travel to congresses from EISAI srl and Inpha 2000; has participated in scientific advisory boards for EISAI; has participated in pharmaceutical industry-sponsored symposia for UCB Pharma; has received research grants from UCB Pharma. Other authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Marta Maschio  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3075-4108

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3075-4108

References

- 1. Argyriou AA, Bruna J, Marmiroli P, Cavaletti G. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity (CIPN): an update. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;82:51-77. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morawska M, Grzasko N, Kostyra M, Wojciechowicz J, Hus M. Therapy-related peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma patients. Hematol Oncol. 2015;33:113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malhotra P, Choudhary PP, Lal V, Varma N, Suri V, Varma S. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma at initial diagnosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:2135-2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramchandren S, Lewis RA. An update on monoclonal gammopathy and neuropathy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12:102-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koeppen S. Treatment of multiple myeloma: thalidomide-, bortezomib-, and lenalidomide-induced peripheral neuropathy. Oncol Res Treat. 2014;37:506-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richardson PG, Xie W, Mitsiades C, et al. Single-agent bortezomib in previously untreated multiple myeloma: efficacy, characterization of peripheral neuropathy, and molecular correlations with response and neuropathy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3518-3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sonneveld P, Jongen JL. Dealing with neuropathy in plasma-cell dyscrasias. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2019:423-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Windebank AJ, Grisold W. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2008;13:27-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Antoine JC, Camdessanche JP. Peripheral nervous system involvement in patients with cancer. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:75-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Delforge M, Bladé J, Dimopoulos MA, et al. Treatment-related peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma: the challenge continues. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1086-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fernyhough P, Smith DR, Schapansky J, et al. Activation of nuclear factor-κB via endogenous tumor necrosis factor α regulates survival of axotomized adult sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1682-1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Argyriou AA, Iconomou G, Kalofonos HP. Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Blood. 2008;112:1593-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bennett GJ, Paice JA. Peripheral neuropathy: experimental findings, clinical approaches. J Support Oncol. 2007;5:61-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park SB, Goldstein D, Krishnan AV, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: a critical analysis. CA Cancer J Clinic. 2013;63:419-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Badros A, Goloubeva O, Dalal JS, et al. Neurotoxicity of bortezomib therapy in multiple myeloma: a single-center experience and review of the literature. Cancer. 2007;110:1042-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghobrial IM, Rajkumar SV. Management of thalidomide toxicity. J Support Oncol. 2003;1:194-205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2609-2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. US Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Version 4. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_40. Published May 28, 2009. Accessed November 1, 2009.

- 19. Mateos MV, Miguel JFS. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous formulation of bortezomib versus the conventional intravenous formulation in multiple myeloma. Ther Adv Hematol. 2012;3:117-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Terpos E, Kleber M, Engelhardt M, et al. European Myeloma Network guidelines for the management of multiple myeloma-related complications. Haematologica. 2015;100:1254-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bilinska M, Usnarska-Zubkiewicz L, Pokryszko-Dragan A. Bortezomib-induced painful neuropathy in patients with multiple myeloma. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2013;17:421-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1941-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schloss JM, Colosimo M, Airey C, Masci PP, Linnane AW, Vitetta L. Nutraceuticals and chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): a systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:888-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith EM, Pang H, Cirrincione C, et al. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy; a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1359-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pachman DR, Barton DL, Watson JC, Loprinzi CL. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: prevention and treatment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:377-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saif MW, Reardon J. Management of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1:249-258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang LL, Wang YH, Shao ZH, Ma J. Prophylaxis of Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with multiple myeloma by high-dose intravenous mecobalamin [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye XueZaZhi. 2017;25:480-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Callender N, Markovina S, Eickhoff J, et al. Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) for the prevention of chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma treated with bortezomib, doxorubicin and low-dose dexamethasone: a study from the Wisconsin Oncology Network. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:875-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rossini G, Stankov BM. Alpha-lipoic acid and docosahaenoicacid. A positive interaction on the carrageenan inflammatory response in rats. Nutrafoods. 2010;9:21-25. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papanas N, Ziegler D. Efficacy of alpha-lipoic acid in diabetic neuropathy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15:2721-2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ziegler D, Hanefeld M, Ruhnau KJ, Hasche H, Lobisch M, Schütte K, Kerum G, Malessa R. Treatment of symptomatic diabetic polyneuropathy with the antioxidant alpha-lipoic acid: a 7-month multicenter randomized controlled trial (ALADIN III Study). ALADIN III Study Group. Alpha-Lipoic Acid in Diabetic Neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(8):1296-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reljanovic M, Reichel G, Rett K, et al. Treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy with the antioxidant thioctic acid (alpha-lipoic acid): a two year multicenter randomized double blind placebo-controlled trial (ALADIN II). Alpha lipoic acid in diabetic neuropathy. Free Radic Res. 1999;31:171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coste TC, Gerbi A, Vague P, Pieroni G, Raccah D. Neuroprotective effect of docosahexaeonic acid-enriched phospholipidis in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes. 2003;52:2578-2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yee P, Weymouth AE, Fletcher EL, Vingrys AJ. A role for omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplements in diabetic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1755-1764. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carlson SE, Colombo J, Gayewsky BJ, et al. DHA supplementation and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:808-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Parente E, Colannino G, Picconi O, Monastra G. Safety of oral alpha-lipoic acid treatment in pregnant women: a retrospective observational study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:4219-4227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mostacci B, Liguori R, Cicero AF. Nutraceutical approach to peripheral neuropathies: evidence from clinical trials. Curr Drug Metab. 2018;19:460-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Teichert J, Tuemmers T, Achenbach H, et al. Pharmacokinetics of alpha-lipoic acid in subjects with severe kidney damage and end-stage renal disease. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:313-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mohan M, Matin A, Davies FE. Update on the optimal use of bortezomib in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Cancer Manag Res. 2017;9:51-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Criteria for diagnosis, staging, risk stratification and response assessment of multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009;23:3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sijben JW, Calder PC. Differential immunomodulation with long-chain n-3 PUFA in health and chronic disease. Proc Nutr Soc. 2007;66:237-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. EFSA Panel on dietetic products, nutrition and allergies. EFSA J. 2009;7:1226. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lu C, Liu Y. Interactions of lipoic acid radical cations with vitamins C and E analogue and hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;406:78-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Galal MK, Khalaf AAA, Ogaly HA, Ibrahim MA. Vitamin E attenuates neurotoxicity induced by deltamethrin in rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cavaletti G, Boglium G, Marzorati L, et al. Grading of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity using the Total Neuropathy Scale. Neurology. 2003;61:1297-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cavaletti G, Frigeni B, Lanzani F, et al. The Total Neuropathy Score as an assessment tool for grading the course of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: comparison with the National Cancer Institute-Common Toxicity Scale. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2007;12:210-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scott J, Huskisson EC. Graphic representation of pain. Pain. 1976;2:175-184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Apolone G, Filiberti A, Cifani S, Ruggiata R, Mosconi P. Evaluation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire: a comparison with SF-36 Health Survey in a cohort of Italian long-survival cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:549-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Postma TJ, Aaronson NK, Heimans JJ, et al. ; EORTC Quality of Life Group. The development of an EORTC quality of life questionnaire to assess chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: the QLQ-CIPN20. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1135-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Katz TF, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standard measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Velasco R, Petit J, Clapés V, Verdú E, Navarro X, Bruna J. Neurological monitoring reduces the incidence of bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma patients. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2010;15:17-25. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2010.00248.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, et al. CTCAEv3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:176-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. A’Hern RP. Sample size tables for exact single-stage phase II designs. Stat Med. 2001;20:859-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Drach J, et al. ; International Myeloma Working Group. International Myeloma Working Group molecular classification of multiple myeloma: spotlight review. Leukemia. 2009;23:2210-2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lanzani F, Mattavelli L, Frigeni B, et al. Role of a pre-existing neuropathy on the course of bortezomib-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2008;13:267-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Richardson PG, Briemberg H, Jagannath S, et al. Frequency, characteristics and reversibility of peripheral neuropathy during treatment of advanced multiple myeloma with bortezomib. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3113-3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Orlowsky RZ, Voorhees PM, Garcia RA, et al. Phase 1 trial of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2005;105:3058-3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Aghajanian C, Dizon DS, Sabbatini P, Raizer JJ, Dupont J, Spriggs DR. Phase I trial of bortezomib and carboplatin in recurrent ovarian or primary peritoneal cancer. J Clin Oncol.2005;23:5939-5943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Boyette-Davis JA, Cata JP, Zhang H, et al. Follow-up psychophysical studies in bortezomib-related chemoneuropathy patients. J Pain. 2011;12:1017-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cavaletti G, Nobile-Orazio E. Bortezomib-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: still far from a painless gain. Haematologica. 2007;92:1308-1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lakshman A, Modi M, Prakash G, et al. Evaluation of bortezomib-induced neuropathy using Total Neuropathy Score (reduced and clinical versions) and NCI CTCAE v4.0 in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma receiving bortezomib-based induction. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17:513-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jordan K, Schaffrath J, Jahn F, Mueller-Tidow C, Jordan B. Neuropharmacology and management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel). 2014;9:246-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Alberti P, Rossi E, Cornblath DR, et al. ; CI-PeriNomS Group. Physician-assessed and patient-reported outcome measures in chemotherapy-induced sensory peripheral neurotoxicity: two sides of the same coin. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:257-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Beijers AJM, Vreugdenhil G, Oerlemans S, et al. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy in multiple myeloma: influence on quality of life and development of a questionnaire to compose common toxicity criteria grading for use in daily clinical practice. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2411-2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Maschio M, Zarabla A, Maialetti A, et al. Prevention of bortezomib-related peripheral neuropathy with docosahexaenoic acid and α-lipoic acid in patients with multiple myeloma: preliminary data. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:1115-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Guo Y, Jones D, Palmer JL, et al. Oral alpha-lipoic acid to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1223-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Paksoy M, Ayduran E, Sanlı A, et al. The protective effects of intratympanic dexamethasone and vitamin E on cisplatin-induced ototoxicity are demonstrated in rats. Med Oncol. 2011;28:615-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wiernik PH, Yeap B, Vogl SE, et al. Hexamethylmelamineand low or moderate dose cisplatin with or without pyridoxine for treatment of advanced ovarian carcinoma: a study of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Cancer Invest. 1992;10:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cascinu S, Catalano V, Cordella L, et al. Neuroprotective effect of reduced glutathione on oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3478-3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ghoreishi Z, Esfahani A, Djazayeri A, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids are protective against paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy: a randomised double-blind placebo controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bianchi G, Vitali G, Caraceni A, et al. Symptomatic and neurophysiological responses of paclitaxel- or cisplatin induced neuropathy to oral acetyl-L-carnitine. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1746-1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hershman DL, Unger JM, Crew KD, et al. Two-year trends of taxane-induced neuropathy in women enrolled in a randomized trial of acetyl-l-carnitine (SWOG S0715). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:669-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Meregalli C. An overview of bortezomib-induced neurotoxicity. Toxics. 2015;3:294-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Shah A, Hoffman EM, Mauermann ML, et al. Incidence and disease burden of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in a population-based cohort. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:636-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Schloss J, Colosimo M, Vitetta L. New insights into potential prevention and management options for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2016;3:73-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Koh Y, Lee SY, Kim I, et al. Bortezomib-associated peripheral neuropathy requiring medical treatment is decreased by administering the medication by subcutaneous injection in Korean multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:653-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bechakra M, Nieuwenhoff MD, Van Rosmalen J, et al. Clinical, electrophysiological, and cutaneous innervation changes in patients with bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy reveal insight into mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Mol Pain. 2018;14:1744806918797042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Heng LJ, Qi R, Yang RH, Xu GZ. Docosahexaenoic acid inhibits mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgia in diabetic rats by decreasing the excitability of DRG neurons. Exp Neurol. 2015;271:291-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lewis EJH, Perkins BA, Lovblom LE, Bazinet RP, Wolever TMS, Bril V. Effect of omega-3 supplementation on neuropathy in type 1 diabetes: a 12-month pilot trial. Neurology. 2017;88:2294-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]