Abstract

Roxadustat (FG-4592), an analog of 2-oxoglutarate, is an orally-administered, heterocyclic small molecule known to be an inhibitor of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylase. However, none of the studies have thus far thoroughly investigated its possible perturbations on membrane ion currents in endocrine or heart cells. In our studies, the whole-cell current recordings of the patch-clamp technique showed that the presence of roxadustat effectively and differentially suppressed the peak and late components of IK(DR) amplitude in response to membrane depolarization in pituitary tumor (GH3) cells with an IC50 value of 5.71 and 1.32 μM, respectively. The current inactivation of IK(DR) elicited by 10-sec membrane depolarization became raised in the presence of roxadustatt. When cells were exposed to either CoCl2 or deferoxamine (DFO), the IK(DR) elicited by membrane depolarization was not modified; however, nonactin, a K+-selective ionophore, in continued presence of roxadustat, attenuated roxadustat-mediated inhibition of the amplitude. The steady-state inactivation of IK(DR) could be constructed in the presence of roxadustat. Recovery of IK(DR) block by roxadustat (3 and 10 μM) could be fitted by a single exponential with 382 and 523 msec, respectively. The roxadustat addition slightly suppressed erg-mediated K+ or hyperpolarization-activated cation currents. This drug also decreased the peak amplitude of voltage-gated Na+ current with a slowing in inactivation rate of the current. Likewise, in H9c2 heart-derived cells, the addition of roxadustat suppressed IK(DR) amplitude in combination with the shortening in inactivation time course of the current. In high glucose-treated H9c2 cells, roxadustat-mediated inhibition of IK(DR) remained unchanged. Collectively, despite its suppression of HIF prolyl hydroxylase, inhibitory actions of roxadustat on different types of ionic currents possibly in a non-genomic fashion might provide another yet unidentified mechanism through which cellular functions are seriously perturbed, if similar findings occur in vivo.

Keywords: roxadustat, delayed-rectifier K+ current, voltage-gated Na+ current, current kinetics, pituitary cell and heart cell

1. Introduction

The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway alters gene expression in response to low oxygen tension. Under normal conditions, HIF-specific prolyl hydroxylases (HIF-PHs) initiate the degradation of oxygen-sensitive HIF isoforms.

Roxadustat (FG-4592, 47 N-[(4-hydroxy-1-methyl-7-phenoxy-3-isoquinolinyl) carbonyl]-glycine, Ai Rui Zhuo® in China), an analog of 2-oxoglutarate, is an orally administered, heterocyclic small molecule, known to inhibit HIF prolyl hydroxylases [1]. Of note, there are a growing number of studies to show that this drug could suppress HIF degradation and in this way induce erythropoietin expression, hence promoting erythropoiesis or preventing anemia in vivo [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11].

Roxadustat has been also demonstrated to have therapeutic potential either for Parkinson’s diseases occurring in vitro or in vivo, for experimental retinal detachment, or for spinal cord injury, which are possibly through its regulation of redox reaction and mitochondrial function [5,12,13,14,15]. Alternatively, this compound could effectively exert neuroprotective effects against photoreceptor or neuronal cell death and prevent liver ischemia-reperfusion injury to donation after cardiac death [13,15,16]. The activity of KV channels (e.g., eag1-mediated K+ channels) has been noted to be associated with oxygen homeostats and induction of angiogenesis in certain types of tumors [17]. Of particular interest, the HIF-1α expression in pituitary gland including pituitary tumor (GH3) cells has shown that it is closely linked to the occurrence or progression of pituitary adenoma [16,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

On the other hand, roxadustat was reported to possess some unexpected side effects [25]. For example, a recent study demonstrated that inhibitors of HIF prolyl hydroxylases could effectively exert neuroprotective actions which are thought to be independent of its inhibitory effects on HIF prolyl hydroxlyases [26]. Roxadustat was also found to exert direct effects on skeletal myotube [27]. However, of note, whether roxadustat is capable of producing any perturbations on the level of surface membrane including on ionic channels in different types of cells is not thoroughly investigated, despite its clinical approval for anemia in chronic kidney disease with or without the dialysis [1,4,5,8,9,10].

Because of the aforementioned considerations, rising attempts were made to evaluate whether roxadustat or other related compounds could produce any modifications on various types of ionic currents (e.g., delayed-rectifier K+ current [IK(DR)], erg-mediated K+ current [IK(erg)], and voltage-gated Na+ current [INa]) in pituitary tumor (GH3) cells. Moreover, earlier numerous studies have reported the effective regulations of HIF-1α expression present in heart-derived H9c2 myoblasts [24,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Thus, we further decided to investigate the possible actions of roxadustat on IK(DR) in these cells. In the present study, we provide the evidence to unravel that roxadustat is able to modify membrane ionic currents in pituitary tumor (GH3) cells and in cardiac H9c2 cells, those actions of which are conceivably of clinical or pharmacological relevance and tend to be upstream of its inhibitory action on HIF prolyl hydroxylases.

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Roxadustat on Delayed-Rectifier K+ Current (IK(DR)) Recorded from Pituitary Tumor (GH3) Cells

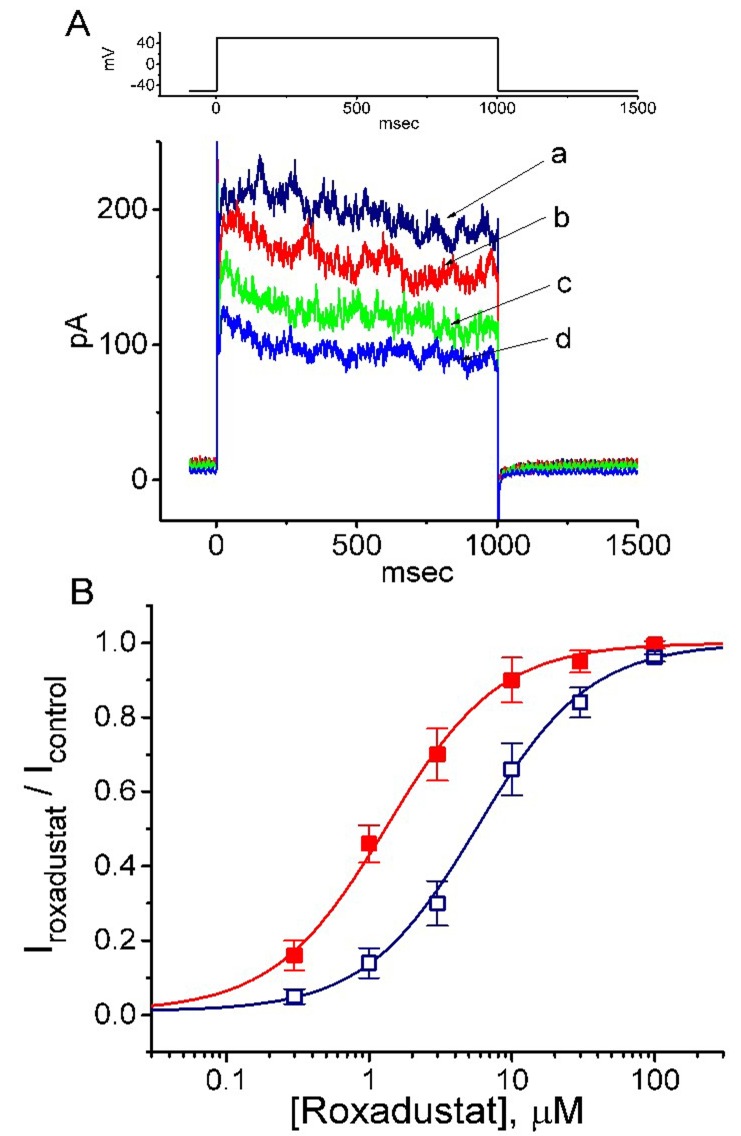

In the first stage of experiments, we examined whether this drug has any perturbation on IK(DR) inherently in these cells. In order to avoid the contamination of Ca2+-activated K+ currents [36,37], we bathed cells in Ca2+-free, Tyrode’s solution, and during the measurements, we filled the recording electrode with a K+-containing solution. The composition of these solutions is detailed above. As the whole-cell configuration was firmly established, we maintained the examined cell at −50 mV and the depolarizing voltage step to +50 mV with a duration of 1 sec was then applied to evoke IK(DR). As shown in Figure 1A, within 1 min of exposing the cell to different roxadustat concentrations, the amplitude of IK(DR) was progressively decreased; moreover, the decaying time course of the current in response to maintained depolarization became faster in their presence. The concentration-dependent relationships of roxadustat effect on IK(DR) amplitude measured at the beginning (i.e., peak current) or end (i.e., late current) of the depolarizing pulse were constructed and are hence plotted in Figure 1B. The IC50 values required for roxadustat-mediated suppression of peak and late IK(DR) were calculated to be 5.71 and 1.32 μM, respectively; however, no measurable change in Hill coefficient of the relationship was found. Therefore, due primarily to the increase of inactivation time course in response to membrane depolarization, the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value for roxadustat was conceivably noted to be fivefold less in IK(DR) amplitude measured at the beginning of depolarizing step than in that at the end of pulse.

Figure 1.

Inhibitory effect of roxadustat on delayed-rectifier K+ current (IK(DR)) in pituitary GH3 cells. In these whole-cell current recordings, cells were bathed in Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution containing 1 μM tetrodotoxin and 5 mM CdCl2, and the recording pipette was backfilled with a K+-containing solution. (A) Representative IK(DR) traces in responses to membrane depolarization (as indicated in the upper part). a: control, b: 0.3 μM roxadustat; c: 1 μM roxadustat; d: 3 μM roxadustat. (B) Concentration-dependent effects of roxadustat on IK(DR). The IK(DR) was evoked by membrane depolarization from −50 to +50 mV. Current amplitudes obtained during cell exposure to different concentrations (0.3–30 μM) of roxadustat were measured at the beginning (□, peak IK(DR)) and end (■, late IK(DR)) of depolarizing pulses. Each point indicates the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM, n = 8–11). The values of IC50 and nH for roxadustat-mediated inhibition of late IK(DR) were estimated to be 1.32 μM and 1.1, respectively, and those for peak IK(DR) were 5.71 μM and 1.1, respectively. Of note, the roxadustat addition is able to differently suppress the amplitude of peak and late IK(DR) in GH3 cells, with no appreciable change in the Hill coefficient of the curve.

2.2. Effect of Roxadustat on the Inactivation Process of IK(DR) Elicited by 10-sec Membrane Depolarization

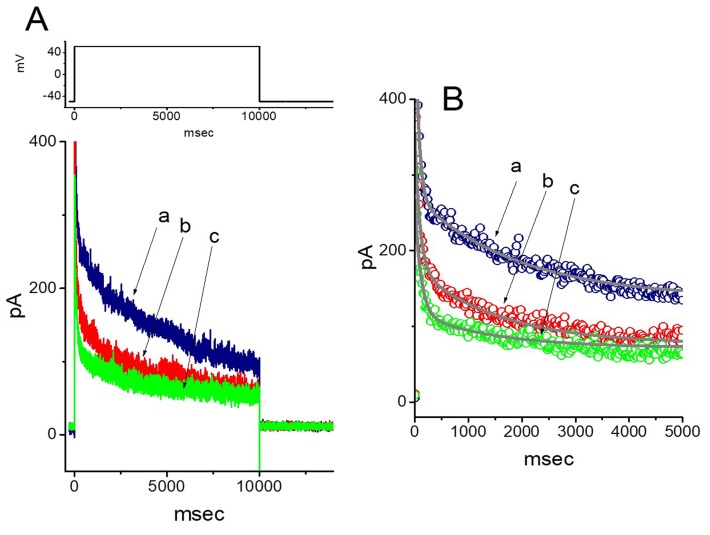

In order to determine the inhibitory effect of roxadustat on the inactivation of IK(DR), a 10 sec long and sustained depolarization from −50 to +50 mV was applied to the cell. As shown in Figure 2, upon 10-sec membrane depolarization, the trajectory of IK(DR) inactivation in the control became slowly decayed with the values of fast (τinact(F)) and slow component (τinact(S)) of current inactivation of 67 ± 9 and 1908 ± 102 msec (n = 9), respectively. Importantly, as the cells were exposed to roxadusat, the inactivation rate of IK(DR) was escalated and the values of τinact(F) and τinact(S) were hence shortened, as evidenced by a significant reduction of τinact(F) and τinact(S) values to 54 ± 8 and 1442 ± 78 msec (n = 9, p < 0.05), respectively, during the exposure to 3 μM roxadustat. After washout of the agent, the values of τinact(F) and τinact(S) returned to 64 ± 7 and 1894 ± 98 msec (n = 7), respectively; moreover, current amplitude returned to the control level. Therefore, roxadustat, in addition to the suppression of current amplitude, was capable of decreasing τinact(F) and τinact(S) values of the current elicited by such long-lasting membrane depolarization.

Figure 2.

Effect of roxadustat on IK(DR) elicited by long-lasting membrane depolarization in GH3 cells. In this set of experiments, the duration of clamp pulse from −50 to +50 mV was maintained for 10 sec, and the tested cells were depolarized from −50 to +50 mV. (A) Representative IK(DR) traces obtained in the control (a), and during the exposure to 1 μM roxadustat (b) and 3 μM roxadustat (c). The upper part denotes the voltage protocol applied. (B) Continuous line in each IK(DR) trajectory corresponds to the least-squares fit to two-exponential function. The data points in each trace were skipped by 20 for clear representation. a: control; b: 1 μM roxadustat; c: 3 μM roxadustat. Of note, the presence of roxadustat, in addition to the reduction of IK(DR) amplitude, decreases the τinact(F) and τinact(S) values of IK(DR) in response to 10-sec membrane depolarization.

2.3. Comparisons among Effects of Roxadustat, CoCl2 and Deferoxamine on IK(DR) Amplitude in GH3 Cells

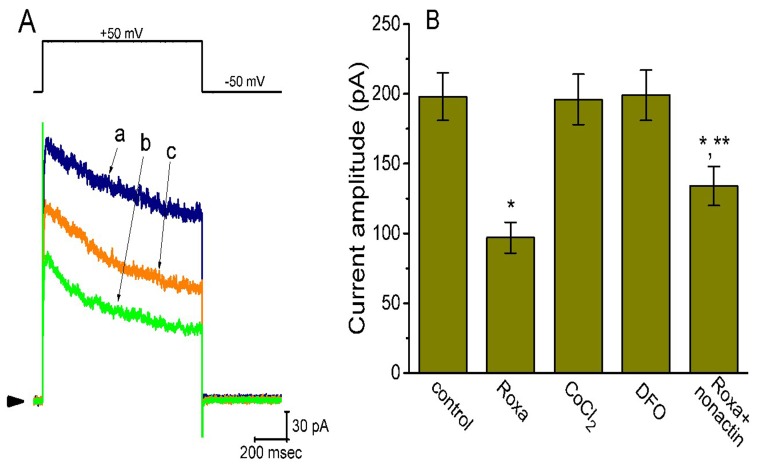

Previous studies have demonstrated that CoCl2 and deferoxamine (DFO, an iron chelator) are hypoxia mimetic reagents. DFO can suppress the activity of iron-dependent prolyl hydroxylase, while CoCl2 activates iron-independent induction of HIF-1α [38]. However, as shown in Figure 3, the addition of CoCl2 or DFO to bath could not modify the IK(DR) elicited in response to membrane depolarization. However, in continued presence of roxadustat (3 μM), subsequent addition of nonactin (10 μM), a K+-selective ionophore, significantly attenuated roxadustat-mediated suppression of IK(DR). As a result, the results led us to reflect that roxadustat-mediated inhibition of IK(DR) in GH3 cells tends to be not attributable to its effect on the accumulation of HIF-1α.

Figure 3.

Comparisons between effects of roxadustat (3 μM), CoCl2 (1 mM), deferoxamine (30 μM), and roxadustat (3 μM) plus nonactin (10 μM) on IK(DR) amplitude in GH3 cells. In these experiments, we bathed cells in Ca2+-free, Tyrode’s solution and the pipette was filled with K+-containing solution. (A) Superimposed IK(DR) obtained in the control (a) and during the exposure to 3 μM roxadustat (b) and 3 μM roxadustat plus 10 μM nonactin (c). The upper part indicates the voltage protocol used and arrowhead in the left side of panel is the zero current level. (B) Summary bar graph showing the effects of roxadustat, CoCl2, deferoxamine, and roxadustat plus nonactin on IK(DR) amplitude. The current amplitude at the end of depolarizing command from −50 to +50 mV was taken. Each bar indicates the mean ± SEM (n = 6–9 for each bar). * Significantly different from control (p < 0.05) and ** significantly different from roxadustat alone group (p < 0.05). Roxa: 3 μM roxadustat; CoCl2: 1 mM CoCl2; DFO: 30 μM deferoxamine; nonactin: 10 μM nonactin.

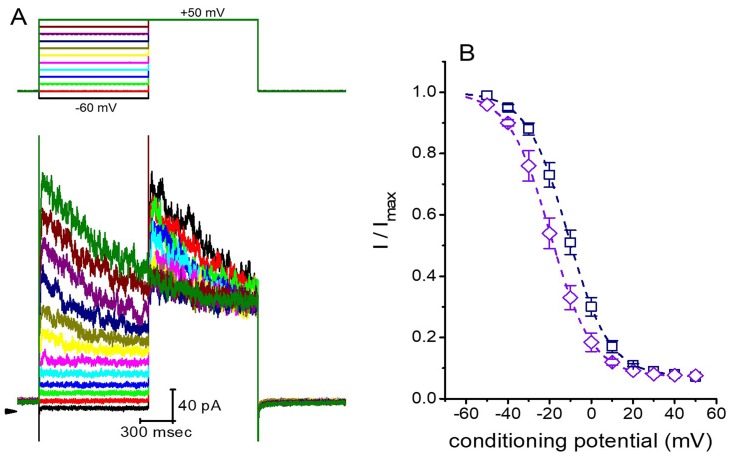

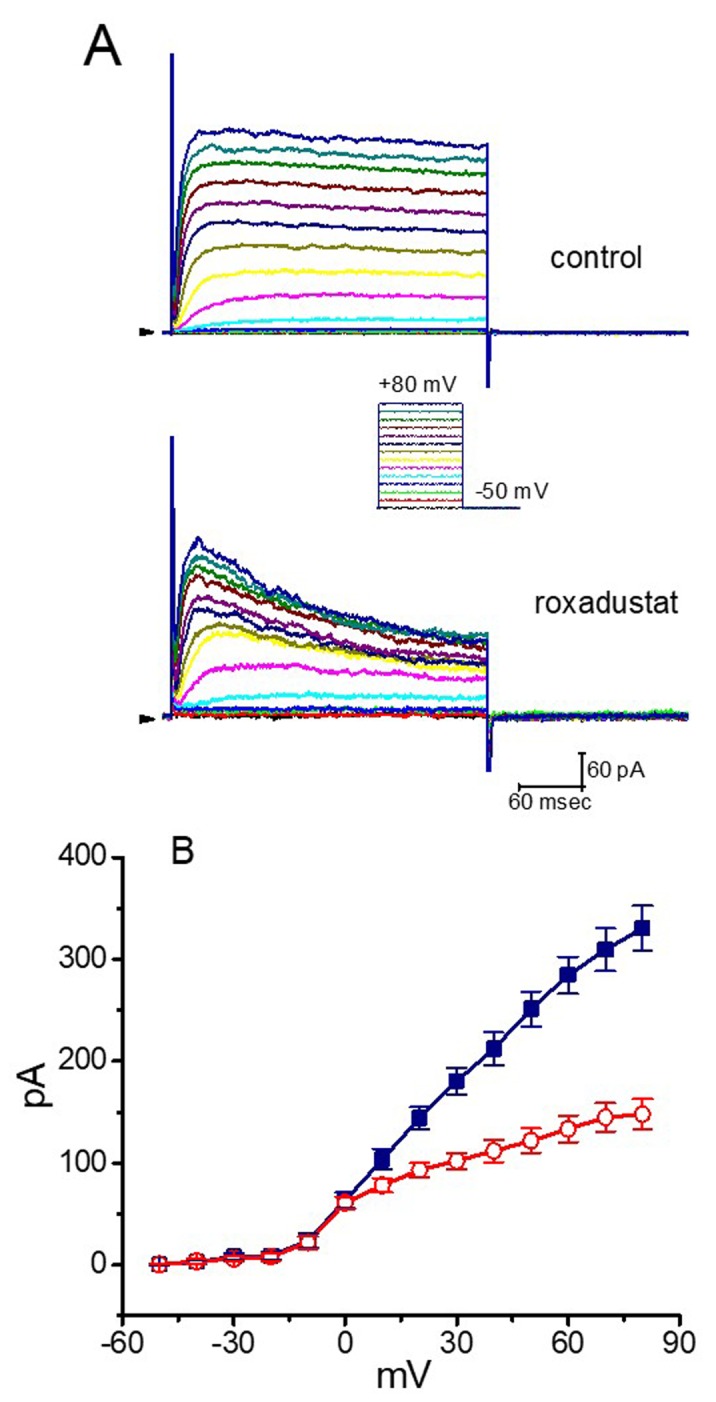

2.4. Effect of Roxadustat on the Steady-State Inactivation Curve of IK(DR) Recorded from GH3 Cells

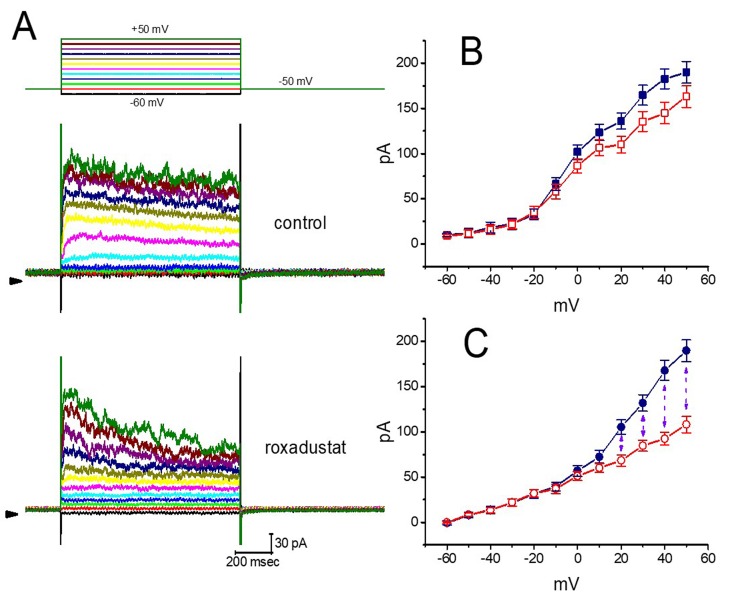

The steady-state inactivation curve of IK(DR) in the presence of roxadustat was further studied. In these experiments, cells were immersed in Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution and the recording electrode was filled with K+-containing solution (Figure 4). As whole-cell configuration was achieved, we applied a two-pulse protocol (i.e., through analog-to-digital conversion) to the examined cells which were exposed to different roxadustat concentrations. The inactivation parameters of IK(DR) were appropriately measured in the presence of 3 or 10 μM roxadustat. As depicted in Figure 5, the normalized amplitudes of IK(DR) (i.e., I/Imax) were constructed against the conditioning potential and the continuous curve was fitted with the goodness of fit by a modified Boltzmann function described under Materials and Methods. In the presence of 3 μM roxadustat, V1/2 = −11.2 ± 1.2 mV, q = 2.6 ± 0.2 e and a = 0.074 ± 0.002 (n = 8), while in the presence of 10 μM roxadustat, V1/2 = -19.4 ± 1.4 mV, q = 2.5 ± 0.2 e and a = 0.074 ± 0.002 (n = 8). Results from these experiments showed that during cell exposure to different roxadustat concentrations, the inactivation parameter (i.e., V1/2 value) of IK(DR) measured from GH3 cells could be altered, despite no appreciable change in the gating charge (q) of the current.

Figure 4.

Averaged current–voltage (I–V) relationships of IK(DR) taken with or without roxadustat addition. In these experiments, the examined cells were maintained at −50 mV and a series of voltage pulses from −60 to +50 mV in 10-mV increments were applied at a rate of 0.1 Hz. (A) Representative IK(DR) traces obtained in the absence (upper) and presence (lower) of 3 μM roxadustat. The upper part indicates the voltage protocol applied and the arrowhead shown in the left inside each panel is the zero current level. Calibration mark in the right lower corner applies to all panels. (B) Averaged I–V relationships of IK(DR) in the control (i.e., in the absence of roxadustat). Current amplitudes at different levels of voltage were measured at the beginning (■) and end (□) of voltage steps. (C) Averaged I–V relationships of IK(DR) in the presence of 3 μM roxadustat. Current amplitudes at different levels of command steps were measured at the beginning (●) and end (○) of voltage steps. Each point shown in (B) and (C) indicates the mean ± SEM (n = 9). The vertical dashed line shown in (C) indicates considerable difference between peak and late IK(DR) as cells were exposed to 3 μM roxadustat.

Figure 5.

Effect of roxadustat on the steady-state inactivation curve of IK(DR) in GH3 cells. These experiments were conducted in a two-step voltage clamp protocol. (A) Representative IK(DR) traces obtained in the presence of 3 μM roxadustat. The upper part denotes the voltage protocol used, and arrowhead in the left side inside panel (A) is zero current level. Calibration mark in the right lower corner applies to all current traces. (B) Steady-state inactivation curve of IK(DR) obtained in the presence of 3 μM (□) and 10 μM roxadustat (◇). Each point indicates the mean ± SEM (n = 8). The smooth curves were least-squares fitted by a Boltzmann function (detailed under Materials and Methods).

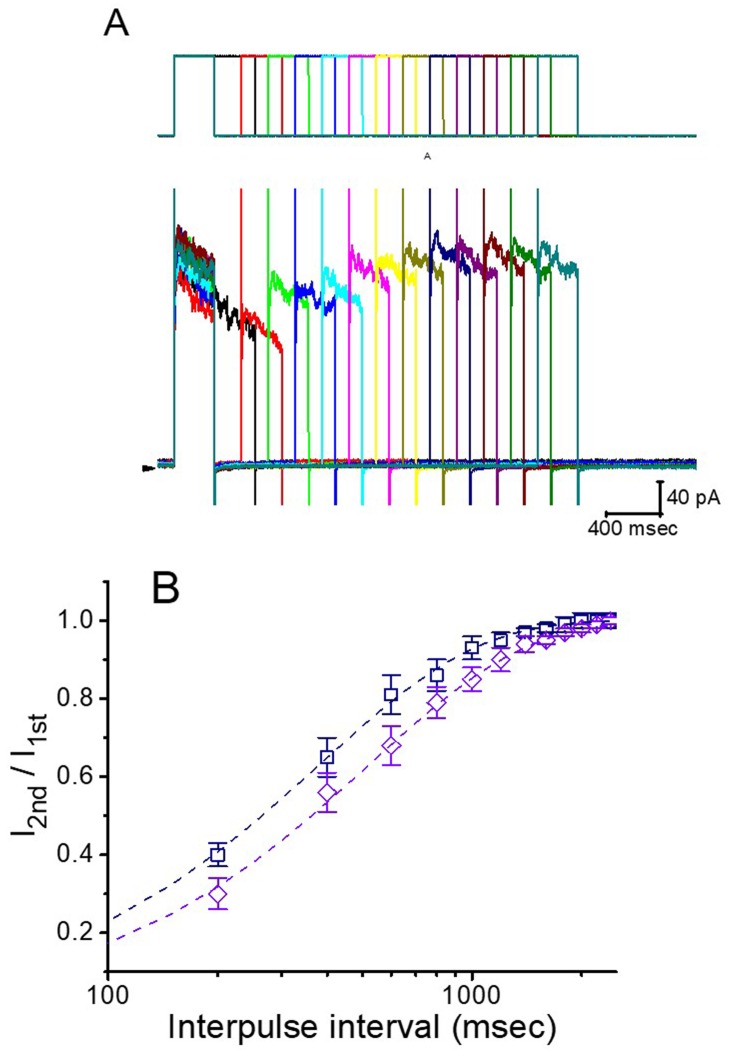

2.5. Effect of Roxadustat on the Recovery of IK(DR) Block in GH3 Cells

In order to evaluate roxadustat-induced block of IK(DR) in these cells, we further investigated the recovery from current inactivation caused by this agent. In this series of experiments, a stimulation protocol consisting of a first (conditioning) depolarizing pulse which is adequately long to allow block to reach a steady state was used. While cells were exposed to roxadustat (3 or 10 μM), the IK(DR) traces were elicited by the following voltage protocol; that is, the membrane potential was stepped to +50 mV from −50 mV for a variable time, after that a second depolarizing pulse (test pulse) was applied at the same potential as the coditioning pulse (Figure 6). Then, the ratios of the peak IK(DR), in response to the second (test, Ipost) and first (conditioning, Ipre) pulse, were taken as a measure of recovery from IK(DR) block and are plotted versus interpulse interval. As depicted in Figure 6, the IK(DR) recovery from block during the exposure to 3 or 10 μM roxadustat was constructed and the time courses could be described by single exponential with the time constants of 382 ± 16 and 523 ± 22 msec (n = 8). It is likely, from the present results, that the recovery of IK(DR) block produced by the presence of roxadustat in GH3 cells was prolonged as its concentration was increased, and that the delayed recovery caused by this agent may result largely from open channel block, as reported previously for aconitine-induced block of IK(DR) [39].

Figure 6.

Time course of the recovery of IK(DR) block in the presence of roxadustat. In these experiments, another set of two-pulse voltage protocol was applied to the examined cells. (A) Superimposed IK(DR) trace in response to two-pulse voltage protocol with different interpulse durations (indicated in the upper part), as the cell was exposed to 3 μM roxadustat. (B) Time course of recovery from IK(DR) inactivation obtained in the presence of 3 μM roxadustat (□) and 10 μM roxadustat (◇) (mean ± SEM; n = 8 for each point). Smooth dashed lines were fitted by single exponential. Note that abscissa (i.e., interpulse interval) in the graph is illustrated at logarithmic scale.

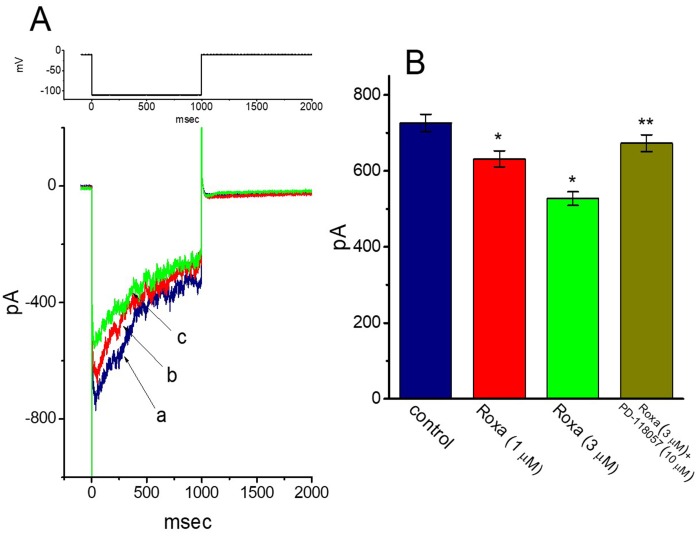

2.6. Effect of Roxadustat on Erg-Mediated K+ Current (IK(erg)) in GH3 Cells

The IK(erg) has been previously reported to be linked to the regulation of HIF (17). We next tested whether roxadustat can modify another type of K+ current (i.e., IK(erg)) which is inherently present in GH3 cells [40,41,42]. These experiments were conducted in cells bathed in high-K+, Ca2+-free solution, and we filled the recording pipette with K+-containing solution. As shown in Figure 7, the deactivating IK(erg) could be readily evoked by membrane hyperpolarization to −110 mV [40]. The addition of 1 or 3 μM roxadustat decreased the peak amplitude of IK(erg) to 632 ± 21 pA (n = 8, p < 0.05) or 527 ± 18 pA (n = 8, p < 0.05), respectively, from a control value of 726 ± 23 pA (n = 8). In the continued presence of 3 μM roxadustat, further addition of 10 μM PD-118057 notably reversed IK(erg) amplitude to 673 ± 22 (n = 8, p < 0.05). PD-118057 was previously shown to activate IK(erg) [43]. Therefore, as compared with its suppressive effect on IK(DR) described above, the IK(erg) in GH3 cells is relatively resistant to modification by roxadustat.

Figure 7.

Effect of roxadustat on erg-mediated K+ current (IK(erg)) in GH3 cells. In this set of experiments, cells were bathed in high-K+, Ca2+-free solution and the recording pipette was filled with K+-containing solution. (A) Representative IK(erg) traces obtained in the absence (a) and presence of 1 μM roxadustat (b) or 3 μM roxadustat (c). The upper part is the voltage protocol used for elicitation of deactivating IK(erg). (B) Summary bar graph showing the effects of roxadustat (Roxa) and roxadustat plus PD-118057 on IK(erg) amplitude in GH3 cells. To evoke deactivating IK(erg), each cell was maintained at -10 mV and the hyperpolarizing pulse to -110 mV with a duration of 1 sec was applied. IK(erg) amplitude was measured at the beginning of hyperpolarizing pulse. Each bar indicates the mean ± SEM (n = 8 for each bar). * Significantly different from control (p < 0.05) and ** significantly different from 3 μM roxadustat alone group.

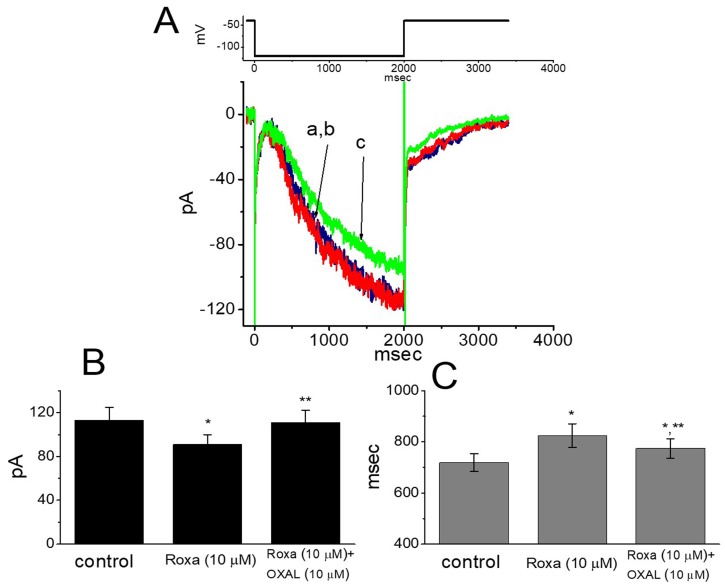

2.7. Suppressive Effect of Roxadustat on Hyperpolarization-Activated Cation Current (Ih) Recorded from GH3 Cells

Whether roxadustat can modify the amplitude and gating of Ih in these cells was further tested in this study. In these experiments, cells were bathed in Ca2+-free, Tyrode’s solution and we filled the patch electrode with K+-containing solution. As the examined cell was maintained at −40 mV, a 2-sec membrane hyperpolarization to −120 mV readily evoked the Ih, the property of which, in accordance with previous observations [44], displayed a considerably slow activation (i.e., a slowly activating inward [depolarizing] current). Moreover, as cells were exposed to 3 μM roxadustat, no significant change in the Ih amplitude by long-lasting hyperpolarizing command was demonstrated. However, as depicted in Figure 8, at 10 μM roxadustat decreased the Ih amplitude from 113 ± 12 to 91 ± 9 pA (n = 8, p < 0.05). Subsequent application of 10 μM oxaliplatin, still in the presence of 10 μM roxadustat, could significantly reverse Ih amplitude to 111 ± 11 pA (n = 8, p < 0.05). Meanwhile, the addition of 10 μM roxadustat raised the activation time constant of Ih from 719 ± 34 to 824 ± 46 msec (n = 8, p < 0.05), and subsequent addition of 10 μM oxaliplatin reduced the time constant of current activation to 774 ± 38 msec (n = 8, p < 0.05). Oxaliplatin was recently noted to increase the amplitude of Ih in response to long-lasting membrane hyperpolarization [25]. Therefore, roxadustat at a concentration of 10 μM can decrease Ih amplitude as well as slow the activation time course of the current.

Figure 8.

Effect of roxadustat on hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) in GH3 cells. These experiments were conducted in cells bathed in Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution and the pipette was filled with K+-containing solution. (A) Representative Ih traces obtained in the absence (a) and presence of 3 μM roxadustat (b) or 10 μM roxadustat (c). The upper part is the voltage protocol used. Panels (B) and (C), respectively, indicate the effect of roxadustat and roxadustat plus oxaliplatin (OXAL) on the amplitude and the activation time constant of Ih elicited by membrane hyperpolarization from −40 to −120 mV with a duration of 2 s. Each bar indicates the mean ± SEM (n = 8 for each bar). * Significantly different from controls (p < 0.05) and ** significantly different from 10 μM roxadustat alone group (p < 0.05).

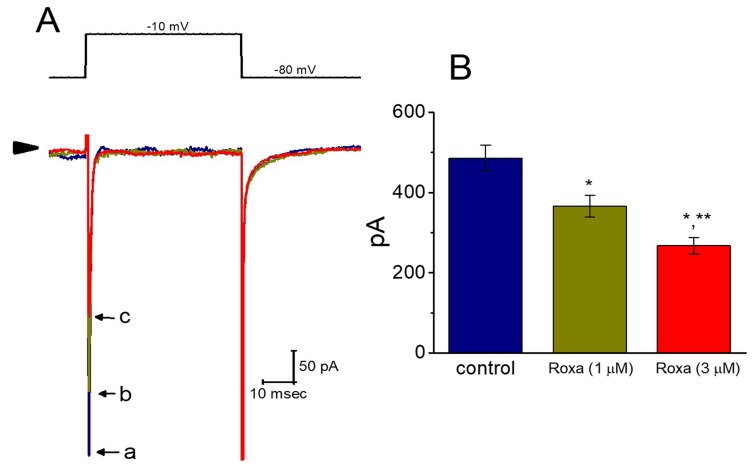

2.8. Inhibitory Effect of Roxadustat on Voltage-Gated Na+ Current (INa) in GH3 Cells

We also ascertained whether the INa present in GH3 cells was subject to any perturbations by roxadustat. In these experiments, cells were bathed in Ca2+-free, Tyrode’s solution, and the recording pipettes used were filled with Cs+-containing solution, the composition of which is detailed under Materials and Methods. As shown in Figure 9, the addition of roxadustat produced a progressive reduction of peak INa in these cells. For example, within 1 min of exposing cells to 1 or 3 μM roxadustat, the peak amplitude of INa in response to rapid membrane depolarization was significantly decreased to 366 ± 27 pA (n = 8, p < 0.05) or 267 ± 21 pA (n = 8, p < 0.05), respectively, from a control value of 486 ± 32 pA (n = 8). After washout of this compound, peak INa was returned to 359 ± 25 pA (n = 8, p < 0.05).

Figure 9.

Effect of roxadustat on voltage-gated Na+ current (INa) in GH3 cells. In these whole-cell recording experiments, we bathed cells in Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution and, during the measurements, we filled the pipette with Cs+-containing solution, the composition of which is described under Materials and Methods. (A) Representative INa traces taken in the control (a) and during cell exposure to 1 μM roxadustat (b) or 3 μM roxadustat (c). The upper part of (A) is the voltage protocol (i.e., the examined cell was rapidly depolarized from −80 mV to −10 mV) and arrowhead denotes the zero current level. (B) Summary bar graph showing the inhibitory effect of roxadustat on peak INa elicited by rapid membrane depolarization from −80 to −10 mV. Current amplitude was measured at the beginning of rapid depolarization. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM (n = 9). * Significantly different from control (p < 0.05) and ** significantly different from 1 μM roxadustat group (p < 0.05). Note that the presence of roxadustat, in addition to the decreased amplitude of peak INa, slowed the inactivation time course of the current.

However, it needs to be mentioned that, as described previously in the telmisartan actions on INa [41], the inactivation rate of INa in response to brief sustained depolarization became slowed in the presence of roxadustat. As cells were exposed to 1 or 3 μM roxadustat, the inactivation time constant of INa was increased to 1.31 ± 0.21 msec (n = 8, p < 0.05) or 1.63 ± 0.35 msec (n = 9, p < 0.05), respectively, from a control value of 0.84 ± 0.17 msec (n = 8). Therefore, distinguishable from roxadustat-induced increase of IK(DR) inactivation, the inactivation rate of peak INa elicited by brief depolarization was apparently depressed in the presence of roxadustat. This occurrence indicates that roxadustat can decrease peak INa amplitude concomitantly with the attenuation of current inactivation rate in GH3 cells.

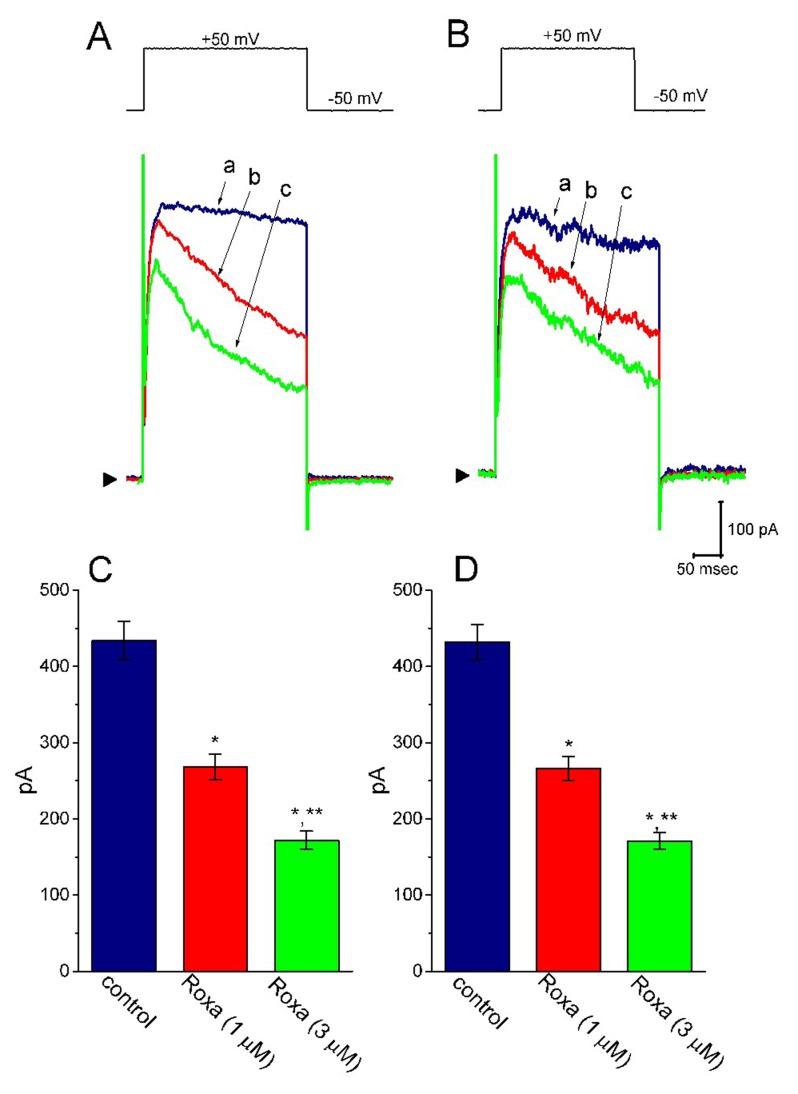

2.9. Effect of Roxadustat on IK(DR) Recorded from Heart-Derived H9c2 Cells

A number of investigations have noted that the expression of HIF-1α in heart-derived H9c2 myoblasts could be delicately regulated [24,28,29,30,31,35]. In another set of experiments, we thus investigated the possible perturbations of roxadustat on IK(DR) inherently in H9c2 cells. As illustrated in Figure 10, the IK(DR) in response to membrane depolarization from −50 mV to a series of voltage steps as described previously [45,46] could be readily evoked with an outwardly rectifying property. Importantly, the presence of 3 μM roxadustat was found to suppress the IK(DR) amplitude effectively elicited throughout the entire voltage-clamp steps in these cells. For example, at the level of +60 mV, the addition of 3 μM roxadustat diminished current amplitude (i.e., late IK(DR)) by 53 ± 3 % from 284 ±18 to 133 ± 13 pA (n = 8, p < 0.05). Similar to the previous results shown in GH3 cells, the presence of roxadustat can significantly but differentially suppress the peak and late amplitude of IK(DR) in cardiac H9c2 cells.

Figure 10.

Effect of roxadustat on IK(DR) recorded from heart-derived H9c2 cells. Experimental protocol used is similar to that for measurement of IK(DR) in GH3 cells. (A) Representative IK(DR) traces obtained in the absence (upper) and presence (lower) of 3 μM roxadustat. Inset indicates the voltage protocol applied. Arrowhead in the left side of each panel marks the zero current level, while calibration mark in the right lower corner applies to all current traces. (B) Averaged I–V relationships of IK(DR) with or without addition of 3 μM roxadustat (mean ± SEM; n = 8 for each point). Current amplitude was measured at the end of 300-msec depolarizing pulse. ■: control; □: in the presence of 3 μM roxadustat.

2.10. Effect of Roxadustat on IK(DR) in High Glucose-Treated H9c2 Cells

Previous studies have demonstrated that roxadustat could alleviate high glucose-induced cell injury [30,47]. The challenging of cells with high glucose has been also shown to suppress the activity of HIF prolyl hydroxylase along with the upregulation of HIF-1α [30,48]. For these reasons, we further studied whether in high glucose-treated H9c2 cells, the biophysical properties of IK(DR) are able to be altered and whether the roxadustat addition could still have any modifications on IK(DR) in these cells. As shown in Figure 11, the IK(DR) in response to membrane depolarization in these cells (i.e., high glucose-treated cells) was quite indistinguishable from that in control cells (i.e., little current inactivation in response to maintained depolarization). Furthermore, within 1 min of exposing high glucose-treated cells to roxadustat, the peak and late amplitudes of IK(DR) were differentially suppressed. For example, roxadustat (3 μM) decreased the late IK(DR) (i.e., current amplitude measured at the end of depolarizing step) from 432 ± 23 to 171 ± 11 (n = 7, p < 0.05) in H9c2 cells treated with high glucose (30 mM). Therefore, the presence of roxadustat remains efficacious at modifying the amplitude and gating of IK(DR) in high glucose-treated cells.

Figure 11.

Effect of roxadustat on IK(DR) in high glucose-treated H9c2 cells. In these experiments, H9c2 cells were incubated in normal glucose (5.5 mM) or high glucose (30 mM) medium for 24 h. In (A) and (B), superimposed IK(DR) traces obtained in the control (a) and during the exposure to 1 μM roxadustat (b) and 3 μM roxadustat (c) were taken in the cell treated with normal glucose (5.5 mM) and high glucose (30 mM), respectively. The upper part in each panel denotes the voltage protocol, the calibration mark in the lower part applies all current trace, and arrowhead at the left side of currents in each panel is the zero current level. In (C,D), summary bar graphs illustrate the effects of roxadustat on the IK(DR) amplitude recorded from H9c2 cells treated with normal glucose (5.5 mM) and high glucose (30 mM), respectively (mean ± SEM; n = 7 for each bar). * Significantly different from control (p < 0.05) and ** significantly different from 1 μM roxadustat alone group (p < 0.05).

3. Discussion

Our results demonstrated that in GH3 cells, the presence of roxadustat (FG-4592) differentially produced an inhibitory action on the peak and late component of IK(DR) in a concentration-dependent manner. The values of τinact(F) and τinact(S) of IK(DR) elicited by 10-sec membrane depolarization were reduced. The steady-state inactivation curve of IK(DR) as well as the recovery of IK(DR) block produced by the presence of roxadustat was clearly demonstrated in this study. However, when cells were exposed to either CoCl2 or DFO, the IK(DR) elicited by membrane depolarization was not modified. This agent slightly suppressed the amplitude of IK(erg) and Ih. It also inhibited INa with a clear slowing in the inactivation rate of the current. The modifications of ionic currents by roxadustat presented herein tend to be acute in onset, and they could be independent of its interaction with HIF prolyl hydroxylases, shortly before the molecules pass through surface membrane. The action of roxadustat on the amplitude and gating IK(DR) is thought to be through its preferential binding to the open-inactivated state(s) of the KV channel.

Roxadustat was previously reported to disrupt mitochondrial oxygen consumption present in skeletal C2C12 myotube [27]. Earlier studies have demonstrated the presence of ATP-sensitive K+ channels functionally expressed in GH3 and H9c2 cells [41,49,50]. It has been also shown that mitochondrial function found in different types of neurons may be stabilized by the presence of roxadustat [12,13,15,51]. However, it is important to note that in our whole-cell current recordings, the pipette solution contained 3 mM ATP, a value that is adequate to suppress the activation of ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels. Furthermore, subsequent addition of diazoxide (10 μM), an activator of KATP channels, but still in the presence of roxadustat, was unable to attenuate roxadustat-mediated inhibition of IK(DR) or Ih amplitude. In this scenario, the inhibition by this agent of ionic currents shown here is, thus, unlikely to be mediated largely through the modifications of KATP-channel activity.

In our study, the addition of CoCl2 or DFO to the bath could not modify the IK(DR) elicited in response to membrane depolarization in GH3 cells. These are hypoxia mimetic regents known to produce the induction of HIF-1α [38]. Moreover, in H9c2 cells preincubated with high glucose (30 mM), the biophysical properties of IK(DR) remained unchanged, i.e., outward K+ current with little inactivation elicited by sustained depolarization. Furthermore, in these cells, roxadustat was also effective at suppressing IK(DR) together with a measurable shortening of inactivation time constant elicited by 10-sec maintained depolarization. The preincubation of H9c2 cells with high-glucose medium was previously reported to suppress HIF prolyl hydroxylase and then to cause the upregulation of HIF [30,48]. Therefore, findings from the present experiments prompted us to propose that the ability of roxadustat to suppress the amplitude of IK(DR), INa, or both is most likely to occur in a non-genomic manner and that it would not be associated with either the inhibition of HIF prolyl hydroxylase or the elevation in the level of HIF [30].

Following a single oral dose of roxadustat at 0.3, 1, 2, 3 or 4 mg/kg, the mean maximal concentrations of roxadustat were previously reported to be 1, 5, 11, 17 and 26 μg/mL (i.e., 2.8, 14.2, 31.2, 48.2 or 73.8 μM), respectively [1,52,53]. In this study, the IC50 values required for roxadustat-mediated inhibition of peak or late IK(DR) in GH3 cells were estimated to be 5.71 or 1.32 μM, respectively. These values are quite close to those that are either therapeutically achievable or needed for the inhibitory actions on HIF prolyl hydroxylases. Alternatively, a concentration-dependent increase by roxadustat in the rate of current inactivation can account largely for differential effectiveness in the reduction in peak and late IK(DR). In other words, the inhibitory action of roxadustat on IK(DR) is shown to correlate over time with a conceivable rise in the inactivation rate of the current elicited in response to long-step membrane depolarization. The IK(DR) recovery from the block during cell exposure to roxadustat was also demonstrated. According to our experimental results, it might be assumed that the blocking site of roxadustat appears to be located within the KV channel pore, only when the channel is open. As such, apart from its inhibitory action at HIF prolyl hydroxylases, the concentration of roxadustat used for both inhibition of ionic currents and modifications in current kinetics (e.g., IK(DR) and INa inactivation, or Ih activation) shown here is conceivably achievable and, thus, of clinical relevance in humans. Findings from the present results would strengthen the notion that the importance of roxadustat-mediated inhibition of HIF prolyl hydroxylase tends to be overestimated, despite the fact that these enzymes could be present in pituitary or heart cells [54]. Roxadustat or other structural similar compounds could also be a family of valuable tools for probing the structure and function of KV channels from the KDR family, as the pore region of the channel protein to which it binds is of particular relevance for open-channel blockade.

Aconitine, a potent cardiotoxin, was previously reported to modify the amplitude and gating of IK(DR) in neurons and heart cells [39,46]. Shenfu injection, the composition of which contains aconitine, has been demonstrated to be beneficial for secondary aplastic anemia induced following chemotherapy via stimulation of bone marrow function [6,55,56]. Previous studies have demonstrated the ability of aconitine to depress IK(DR) amplitude and to fasten the inactivation rate of the current [39,46]. Therefore, because of their similar actions on the amplitude and gating of IK(DR), to what extent changes in the amplitude and gating of IK(DR) by aconitine or roxadustat could produce any stimulatory effects on the function of hematopoietic cells in bone marrow [57] is worthy of being further investigated. Additionally, it needs to be noted that in Kcnk3-mutated rats, a novel model for occurrence of pulmonary hypertension was recently characterized [58].

There are limitations in the present study. Ideally, it would be important to evaluate the effects of roxadustat on ionic currents, when the mRNAs of hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) have been knocked down, and subsequently to test the perturbations on all the ion channels of interest in these cells. However, under our experimental results, the rapid onset of actions of roxadustat on ionic currents seen in GH3 or H9c2 cells were noted. Moreover, the cells in which the HIF-1α mRNAs were knocked-down, would have become too fragile to be accurately studied during the measurements. For example, the activity of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in GH3 or H9c2 cells would have been seriously deranged [27,49,50,54]. Alternatively, in our study, in high-glucose-treated H9c2 cardiac cells, inhibition by roxadustat of the IK(DR) elicited in response to long-lasing membrane depolarization was noted to remain efficacious. It needs to be mentioned that the challenging of cells with high glucose has been demonstrated to suppress the activity of HIF prolyl hydroxylases along with the upregulation of HIF [30,47,48] We also found out that deferoxamine, an inhibitor of iron-dependent prolyl hydroxylase [38], could not modify the amplitude or gating of IK(DR) in GH3 cells. The results thus reflect the fact that roxadustat-mediated inhibition of IK(DR) in GH3 cells tends to be not attributable to its actions on the accumulation of HIF-1α. To what extent roxadustat-mediated modifications of ionic currents can be potentially altered in HIF-1α-knocked down cells remains to be further delineated.

Nonetheless, our studies indeed highlight the notion that, in addition to the inhibition of HIF prolyl hydroxylase, the roxadustat molecule per se is capable of interacting directly with membrane ion channels, thus perturbing the amplitude and gating of ionic currents. Therefore, roxadustat is recognized as a potent and efficacious compound in suppressing ionic currents (e.g., IK(DR)) in a non-genomic pathway. The interaction of roxadustat with the activity of these ion channels presented herein is acute in onset and thus less likely to be linked to the activity of HIF-1α, although the detailed molecular mechanism of its action on ionic currents still needs to be further resolved.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Drugs, Chemicals and Solutions

Roxadustat (FG-4592, ASP1517, AZD9941, Ai Rui Zhuo®, Beijing, China, N-[(4-hydroxy-1-methyl-7-phenoxy-3-isoquinolinyl)carbonyl]-glycine, C19H16N2O5, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Roxadustat) was acquired from Cayman (Excel Biomedical Inc., Taipei, Taiwan), diazoxide, nonactin and PD-118057 were from Tocris (Union Biomed Inc., Taipei, Taiwan), and deferoxamine (DFO), oxaliplatin and tetrodotoxin were from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan). Tissue culture media, fetal calf serum, horse serum, L-glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin, fungizone and trypsin/EDTA were obtained from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA, USA), and other chemicals that include CdCl2, CoCl2, CsCl, CsOH, aspartic acid and HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) were of the best available quality, mostly at analytical grades.

The composition of normal Tyrode’s solution was 136.5 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.53 mM MgCl2, 5.5 mM glucose, and 5.5 mM HEPES-NaOH buffer, pH 7.4. To record IK(DR) or Ih, the patch electrode was filled with the following solution: 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 3 mM Na2ATP, 0.1 mM Na2GTP, 0.1 mM EGTA, and 5 mM HEPES-KOH buffer, pH 7.2. To measure INa, we replaced KCl inside the pipette solution with equimolar CsCl, and pH was adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. To avoid possible contamination of Cl- currents, we substituted aspartate for Cl- ions inside the pipette solution. To measure IK(erg), bath solution was replaced with a high-K+, Ca2+-free solution containing 130 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES-KOH buffer, pH 7.4, and the pipette solution contained 145 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES-KOH buffer, pH 7.2.

4.2. Cell Culture

GH3 pituitary tumor cells, obtained from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center ([BCRC-60015]; Hsinchu, Taiwan), were grown in Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 15% horse serum (v/v), 2.5% fetal bovine serum (v/v), and 2 mM L-glutamine [59]. To promote cell differentiation, GH3 cells were transferred to a serum-free, Ca2+-free medium. The H9c2 cell line, derived from embryonic rat ventricles, was also provided by the Bioresource Collection and Research Center (BCRC-60096). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (v/v) and 2 mM glutamine [45]. GH3 or H9c2 cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified environment of 5% CO2/95% air and sub-cultured weekly and fresh media were replenished every 2–3 days for removal of non-adhering cells. In another separate set of experiments, in attempts to suppress the activity of HIF prolyl hydroxylase [30], we incubated H9c2 cells in high-glucose medium containing 30 mM glucose and 2% fetal bovine serum for 24 h.

4.3. Electrophysiological Measurements

On the day of each experiment, GH3 or H9c2 cells were dissociated and an aliquot of cell suspension was transferred to a custom-built recording chamber firmly mounted on the stage of an inverted DM-IL microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Cells were bathed at room temperature (20–25 °C) in normal Tyrode’s solution, the composition of which is described above. The pipettes were fabricated from Kimax-51 borosilicate capillaries (#34500; Kimble, Vineland, NJ, USA) by using either a PP-83 vertical puller (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) or a P-97 Flaming/Brown horizontal puller (Sutter, Novato, CA, USA). The electrodes used for the recordings had a tip resistance ranging between 3 and 5 MΩ, when they were filled up with different internal solutions described above. Ion currents were measured in the whole-cell mode of standard patch-clamp technique by use of either an RK-400 (Bio-Logic, Claix, France) or an Axopatch 200B (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) patch amplifier [41,59]. All potentials were corrected for liquid–liquid junction potential that would appear, when the composition of the pipette solution remained different from that in the bath. Through digital-to-analog conversion, the voltage-step profiles including one- or two-step pulses digitally, which were created from pCLAMP 10.7 software (Molecular Devices), were particularly designed to establish either the current–voltage (I–V) relations of ionic currents, or the steady-state inactivation and recovery from inactivation of IK(DR).

4.4. Data Recordings

The signals, consisting of potential and current traces, were stored online at 10 kHz in an ASUSPRO-BU401LG computer (ASUS, Taipei City, Taiwan) through a Digidata 1440A interface (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), the device of which was controlled by pCLAMP 10.7 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The laptop computer was put on the top of an adjustable Cookskin stand (Ningbo, Zhejiang, China) for efficient control during the recordings. Current signals were low-pass filtered at 3 kHz. The data digitally acquired during each experiment were analyzed subsequently using different analytical tools that include LabChart 7.0 program (AD Instruments; Gerin, Tainan, Taiwan), OriginPro (Microcal, Northampton, MA, USA), and custom-made macro procedures built under Microsoft ExcelTM 2016 (Redmond, WA, USA).

4.5. Data Analyses

To evaluate concentration-dependent inhibition of roxadustat on the amplitude of IK(DR), cells were bathed in Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution and step depolarizing pulses from −50 to +50 mV with a duration of 1 sec were delivered. The IK(DR) amplitude which was measured at the beginning (i.e., peak component) or end (i.e., late component) of each long-step depolarizing pulse, during cell exposure to different concentrations (0.3–100 μM) of roxadustat was compared with the control value. The concentration-dependent relation of roxadustat on the inhibition of IK(DR) measured in GH3 cells was established by fitting the data with the goodness of fit to a modified form of the Hill equation. That is, where [Roxa], IC50, and nH are the roxadustat concentration used, the concentration required for a 50% inhibition, and Hill coefficient, respectively; and, A or a represents the maximal fraction of total current (peak and late component) which is roxadustat sensitive or insensitive, respectively.

| (1) |

To determine the steady-state inactivation curve of IK(DR) during cell exposure to different roxadustat concentrations, the relationships between the normalized amplitude of IK(DR) and the conditioning potentials obtained in the presence of 3 or 10 μM roxadustat were least-squares fitted with a modified Boltzmann function of the following form:

| (2) |

where Imax is the maximal peak amplitude of IK(DR) taken at the level of +50 mV, V1/2 the voltage at which half-maximal inhibition occurs, q the apparent gating charge of the inactivation curve, F Faraday’s constant, R the universal gas constant, T the absolute temperature, and a the residual fraction of the current.

4.6. Statistical Analyses

Linear or non-linear curve-fitting (e.g., single or two exponential, or sigmoidal fitting) to data sets was performed with the goodness of fit by using different maneuvers such as Microsoft Solver function embedded in Excel 2016 (Microsoft) and 64-bit OriginPro 2016 program (OriginLab). The averaged results are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) with sample sizes (n) indicating the cell numbers from which the results were collected. The paired or unpaired Student’s t-test and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc Fisher’s least-significance difference method, were implemented for statistical evaluation of differences among means. If normality underlying ANOVA was presumably violated, we attempted to use the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 20 statistical software package (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). Statistical significance was determined at a p-value of <0.05.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, we found that roxadustat was effective at modifying the amplitude and gating of IK(DR) in GH3 and H9c2 cells. The modification of aconitine on IK(DR) was reported to aberrantly prolong action potential in heart cells, in combination with the emergence of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Therefore, whether roxadustat caused any serious complications in heart function needs to be determined as an imperative, despite a previous study showing little or no occurrence of serious adverse cardiac events during roxadustat treatment. Nonetheless, our study reveals another unidentified but important aspect which needs to be given due consideration, despite the inhibitory actions of either roxadustat or other structurally similar compounds on the activity of HIF prolyl hydroxylase inside the cell. Such actions on these ionic currents are of particular clinical, pharmacological or toxicological relevance.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Kaisen Lee and Sih-Wei Li for technical assistances in earlier work.

Abbreviations

| DFO | Deferoxamine |

| erg | ether-à-go-go-related gene |

| HIF | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| IC50 | The concentration required for 50% inhibition |

| I h | Hyperpolarization-activated cation current |

| I K(DR) | Delayed-rectifier K+ current |

| I K(erg) | erg-mediated K+ current |

| I Na | Voltage-gated Na+ current |

| KATP channel | ATP-sensitive K+ channel |

| roxadustat | (FG-4592, N-[(4-hydroxy-1-methyl-7-phenoxy-3-isoquinolinyl)carbonyl]-glycine) |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| τinact(F) | Fast component of inactivation time constant |

| τinact(S) | Slow component of inactivation time constant |

Author Contributions

S.-N.W. was responsible for the study design. Z.-H.G., Y.-C.L. and S.-N.W. were involved in conducting the experiments. W.-T.C. and S.-N.W. wrote the manuscript with editing help from all co-authors.

Funding

The research detailed in this paper is partly supported by grants from National Cheng Kung University (D107-F2519, D108-F2507, NCKUH-10709001 and CMNCKU10703), and from Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST-108-2314-B-006-094), Taiwan, all of which are through a contract awarded to S.N. Wu, while the grant named CMNCKU10703 was awarded to W.T. Chang and S.N. Wu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dhillon S. Roxadustat: First global approval. Drugs. 2019;79:563–572. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruegge K., Jelkmann W., Metzen E. Hydroxylation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors and chemical compounds targeting the HIF-α hydroxylases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007;14:1853–1862. doi: 10.2174/092986707781058850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsieh M.M., Linde N.S., Wynter A., Metzger M., Wong C., Langsetmo I., Klaus S.J. HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibition results in endogenous erythropoietin induction, erythrocytosis, and modest fetal hemoglobin expression in rhesus macaques. Blood. 2007;110:2140–2147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Provenzano R., Besarab A., Wright S., Dua S., Zeig S., Nguyen P., Szczech L. Roxadustat (FG-4592) versus epoetin alfa for anemia in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: A phase 2, randomized, 6- to 19-week, open-label, active-comparator, dose-ranging, safety and exploratory efficacy study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016;67:912–924. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Vecchio L., Locatelli F. Roxadustat in the treatment of anaemia in chronic kidney disease. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2018;27:125–133. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2018.1417386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joharapurkar A.A., Pandya V.B., Patel V.J., Desai R.C., Jain M.R. Prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors: A breakthrough in the therapy of anemia associated with chronic diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:6964–6982. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong H., Zhou T., Li H., Zhong Z. The role of hypoxia-inducible factor stabilizers in the treatment of anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2018;12:3003–3011. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S175887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen N., Hao C., Peng X., Lin H., Yin A., Hao L., Chen J. Roxadustat for anemia in patients with kidney disease not receiving dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:1001–1010. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen N., Hao C., Liu B.C., Lin H., Wang C., Xing C., Zuo L. Roxadustat treatment for anemia in patients undergoing long-term dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:1011–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan J. Roxadustat and anemia of chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:1070–1072. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1908978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanghani N.S., Haase V.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor activators in renal anemia: Current Clinical Experience. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019;26:253–266. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain I.H., Zazzeron L., Goli R., Alexa K., Schatzman-Bone S., Dhillon H., Zhang F. Hypoxia as a therapy for mitochondrial disease. Science. 2016;352:54–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H., Zhu H., Li T., Zhang P., Wang N., Sun X. Prolyl-4-hydroxylases inhibitor stabilizes HIF-1α and increases mitophagy to reduce cell death after experimental retinal detachment. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016;57:1807–1815. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu K., Zhou K., Wang Y., Zhou Y., Tian N., Wu Y., Zhang X. Stabilization of HIF-1α by FG-4592 promotes functional recovery and neural protection in experimental spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 2016;1632:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo C.W., Tsai M.H., Lin T.K., Tiao M.M., Wang P.W., Chuang J.H., Liou C.W. mtDNA as a mediator for expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and ROS in hypoxic neuroblastoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1220. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X., Liu Z., Xiao Q., Zeng C., Lai C.H., Fan X., Xiong Y. Donor treatment with a hypoxia-inducible factor-1 agonist prevents donation after cardiac death liver graft injury in a rat isolated perfusion model. Artif. Organs. 2018;42:280–289. doi: 10.1111/aor.13005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downie B.R., Sánchez A., Knötgen H., Contreras-Jurado C., Gymnopoulos M., Weber C., Pardo L.A. Eag1 expression interferes with hypoxia homeostasis and induces angiogenesis in tumors. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:36234–36240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801830200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida D., Kim K., Yamazaki M., Teramoto A. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and cathepsin D in pituitary adenomas. Endocr. Pathol. 2005;16:123–131. doi: 10.1385/EP:16:2:123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shan B., Gerez J., Haedo M., Fuertes M., Theodoropoulou M., Buchfelder M., Renner U. RSUME is implicated in HIF-1-induced VEGF-A production in pituitary tumour cells. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2012;19:13–27. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shan B., Schaaf C., Schmidt A., Lucia K., Buchfelder M., Losa M., Stalla G.K. Curcumin suppresses HIF1A synthesis and VEGFA release in pituitary adenomas. J. Endocrinol. 2012;214:389–398. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang K., Yang Y., Wang D., Xie B., Li X., Xu B. HIF-1α Inhibition Sensitized pituitary adenoma cells to temozolomide by regulating presenilin 1 expression and autophagy. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2016;15:NP95–NP104. doi: 10.1177/1533034615618834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouroupi M., Sivridis E., Papazoglou D., Koukourakis M.I., Giatromanolaki A. Hypoxia inducible factor expression and angiogenesis—Analysis in the pituitary gland and patterns of death. Vivo. 2018;32:185–190. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinali B., Senoglu M., Karadag F.K., Karadag A., Middlebrooks E.H., Oksuz P., Diniz G. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A expression in pituitary adenomas: Association with pathological, clinical, and radiological features. World Neurosurg. 2019;121:e716–e722. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang L., Wu J., Xie P., Yu J., Li X., Wang J., Zheng H. Sevoflurane postconditioning alleviates hypoxia-reoxygenation injury of cardiomyocytes by promoting mitochondrial autophagy through the HIF-1/BNIP3 signaling pathway. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7165. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dini L., Del Lungo M., Resta F., Melchiorre M., Spinelli V., Di Cesare Mannelli L., Mannaioni G. Selective blockade of HCN1/HCN2 channels as a potential pharmacological strategy against pain. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:1252. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vetrovoy O., Rybnikova E. Neuroprotective action of PHD inhibitors is predominantly HIF-1-independent. J. Neurochem. 2019;150:645–647. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishi H., Takemura K., Higashihara T., Nangaku M. HIF stabilizer decreases mitochondrial oxygen consumption in skeletal C2C12 myotube. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019;34(Suppl. 1):gfz096-FO013. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfz096.FO013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu N., Zhang X., Du S., Chen D., Che R. Upregulation of miR-335 ameliorates myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury via targeting hypoxia inducible factor 1-alpha subunit inhibitor. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018;10:4082–4094. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Z.Y., Wang F., Jia C.H., Xie M.L. Apigenin-induced HIF-1α inhibitory effect improves abnormal glucolipid metabolism in Ang/hypoxia-stimulated or HIF-1α-overexpressed H9c2 cells. Phytomedicine. 2018;62:152713. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y.T., Liu C.H., Yang Y.C., Aneja R., Wen S.Y., Huang C.Y., Kuo W.W. ROS- and HIF1α-dependent IGFBP3 upregulation blocks IGF1 survival signaling and thereby mediates high-glucose-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234:13557–13570. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lakshmi Sundaram R., Vasanthi H.R. Dalspinin isolated from Spermacoce hispida (Linn.) protects H9c2 cardiomyocytes from hypoxic injury by modulating oxidative stress and apoptosis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019;241:111962. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.111962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu D.W., Zhang Y.N., Hu H.J., Zhang P.Q., Cui W. Downregulation of microRNA-199a-5p attenuates hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cytotoxicity in cardiomyocytes by targeting the HIF1α-GSK3β-mPTP axis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019;19:5335–5344. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pu J., Zhu S., Zhou D., Zhao L., Yin M., Wang Z., Hong J. Propofol alleviates apoptosis induced by chronic high glucose exposure via regulation of HIF-1α in H9c2 cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019;2019:4824035. doi: 10.1155/2019/4824035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J., Gao T., Wang F., Xue J., Ye H., Xie M. Luteolin improves myocardial cell glucolipid metabolism by inhibiting hypoxia inducible factor-1α expression in angiotensin II/hypoxia-induced hypertrophic H9c2 cells. Nutr. Res. 2019;65:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu H., Chen B., Ren Q. Baicalin relieves hypoxia-aroused H9c2 cell apoptosis by activating Nrf2/HO-1-mediated HIF1α/BNIP3 pathway. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019;47:3657–3663. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1657879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu S.N., Li H.F., Jan C.R., Shen A.Y. Inhibition of Ca2+-activated K+ current by clotrimazole in rat anterior pituitary GH3 cells. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:979–989. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen P.C., Ruan J.S., Wu S.N. Evidence of decreased activity in intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels during retinoic acid-induced differentiation in motor neuron-like NSC-34 cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;48:2374–2388. doi: 10.1159/000492653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Triantafyllou A., Liakos P., Tsakalof A., Georgatsou E., Simos G., Bonanou S. Cobalt induces hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) in HeLa cells by an iron-independent, but ROS-, PI-3K- and MAPK-dependent mechanism. Free Radic. Res. 2006;40:847–856. doi: 10.1080/10715760600730810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin M.W., Wang Y.J., Liu S.I., Lin A.A., Lo Y.C., Wu S.N. Characterization of aconitine-induced block of delayed rectifier K+ current in differentiated NG108-15 neuronal cells. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:912–923. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y.C., Wu S.N. Block of erg current by linoleoylamide, a sleep-inducing agent, in pituitary GH3 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;458:37–47. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)02728-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu S.N., Yang W.H., Yeh C.C., Huang H.C. The inhibition by di(2-ethylhexyl)-phthalate of erg-mediated K+ current in pituitary tumor (GH3) cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2012;86:713–723. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0805-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang W.T., Wu S.N. Activation of voltage-gated sodium current and inhibition of erg-mediated potassium current caused by telmisartan, an antagonist of angiotensin II type-1 receptor, in HL-1 atrial cardiomyocytes. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018;45:797–807. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou J., Augelli-Szafran C.E., Bradley J.A., Chen X., Koci B.J., Volberg W.A., Cordes J.S. Novel potent human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel enhancers and their in vitro antiarrhythmic activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;68:876–884. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.014035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsiao H.T., Liu Y.C., Liu P.Y., Wu S.N. Concerted suppression of Ih and activation of IK(M) by ivabradine, an HCN-channel inhibitor, in pituitary cells and hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. Bull. 2019;149:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lo Y.C., Yang S.R., Huang M.H., Liu Y.C., Wu S.N. Characterization of chromanol 293B-induced block of the delayed-rectifier K+ current in heart-derived H9c2 cells. Life Sci. 2005;76:2275–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y.J., Chen B.S., Lin M.W., Lin A.A., Peng H., Sung R.J., Wu S.N. Time-dependent block of ultrarapid-delayed rectifier K+ currents by aconitine, a potent cardiotoxin, in heart-derived H9c2 myoblasts and in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;106:454–463. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie R.Y., Fang X.L., Zheng X.B., Lv W.Z., Li Y.J., Rage H.I., Cui T.X. Salidroside and FG-4592 ameliorate high glucose-induced glomerular endothelial cells injury via HIF upregulation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;118:109175. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xia Y., Gong L., Liu H., Luo B., Li B., Li R., An F. Inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase 3 ameliorates cardiac dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015;403:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu S.N., Li H.F., Chiang H.T. Characterization of ATP-sensitive potassium channels functionally expressed in pituitary GH3 cells. J. Membr. Biol. 2000;178:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s002320010028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu S.N., Chang H.D. Diethyl pyrocarbonate, a histidine-modifying agent, directly stimulates activity of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in pituitary GH3 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;71:615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li X., Cui X.X., Chen Y.J., Wu T.T., Xu H., Yin H., Wu Y.C. Therapeutic potential of a prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor FG-4592 for Parkinson’s diseases in vitro and in vivo: Regulation of redox biology and mitochondrial function. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:121. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Groenendaal-van de Meent D., den Adel M., van Dijk J., Barroso-Fernandez B., El Galta R., Golor G., Schaddelee M. Effect of multiple doses of omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of roxadustat in healthy subjects. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2018;43:685–692. doi: 10.1007/s13318-018-0480-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shibata T., Nomura Y., Takada A., Ueno M., Katashima M., Yazawa R., Furihata K. Evaluation of food and spherical carbon adsorbent effects on the pharmacokinetics of roxadustat in healthy nonelderly adult male Japanese subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2019;8:304–313. doi: 10.1002/cpdd.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang H., Zhang G., Gonzalez F.J., Park S.M., Cai D. Hypoxia-inducible factor directs POMC gene to mediate hypothalamic glucose sensing and energy balance regulation. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen G. Effects of Shenfu injection on chemotherapy-induced adverse effects and quality of life in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2018;14:S549–S555. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.187299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kubasch A.S., Platzbecker U. Setting fire to ESA and EMA resistance: New targeted treatment options in lower risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3853. doi: 10.3390/ijms20163853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Forristal C.E., Levesque J.P. Targeting the hypoxia-sensing pathway in clinical hematology. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014;3:135–140. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lambert M., Capuano V., Boet A., Tesson L., Bertero T., Nakhleh M.K., Rucker-Martin C. Characterization of Kcnk3-mutated rat, a novel model of pulmonary hypertension. Circ. Res. 2019;125:678–695. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.314793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu S.N., Chern J.H., Shen S., Chen H.H., Hsu Y.T., Lee C.C., Shie F.S. Stimulatory actions of a novel thiourea derivative on large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017;232:3409–3421. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]