Abstract

Objective

In Mexico specialized treatment services for people with co-occurring disorders are limited within public health services, while private options are deemed too costly. Over 2,000 community-based residential care facilities have risen as an alternative and are the main source of treatment for individuals with substance use disorders; however suboptimal practices within such facilities are common. Information on the clinical characteristics of patients receiving care in these facilities is scarce and capacity to provide high quality care for co-occurring disorders is unknown. The aims of this study were to examine the prevalence of co-occurring disorders in patients receiving treatment for substance use in these community-based residential centers and to assess whether the presence of co-occurring disorders is associated with higher severity of substance use, psychiatric symptomatology and other health risks.

Methods:

This study was conducted with 601 patients receiving treatment for substance use disorders at 30 facilities located in five Mexican states, recruited in 2013 and 2014. Patients were assessed with self-report measures on substance use, service utilization, suicidality, HIV risk behaviors, psychiatric symptomatology and psychiatric disorder diagnostic criteria.

Results:

The prevalence of any co-occurring disorder in this sample was 62.6%. Antisocial personality disorder was the most prevalent (43.8%) followed by major depressive disorder (30.9%). The presence of a co-occurring disorder was associated with higher severity of psychiatric symptoms (aB = .496, SE = .050, p < .05); more days of substance use (aB = .219, SE = .019, p < .05); current suicidal ideation (aOR = 5.07, 95% CI [2.58, 11.17]; p < .05), plans (aOR = 5.17 95% CI [2.44, 12.73];p < .05), and attempts (aOR = 6.43 95% CI [1.83, 40.78];p < .05); more sexual risk behaviors; and more contact with professional services (aOR = 1.77, 95% CI [1.26, 2.49], p < .05).

Conclusions:

Co-occurring disorders are highly prevalent in community-based residential centers in Mexico and are associated with significantly increased probability of other health risks. This highlights the need to develop care standards for this population and the importance of clinical research in these settings.

Keywords: Co-occurring disorders, substance use disorders, suicide, risk behaviors, inpatients, community-based residential care facilities for substance use

1. INTRODUCTION

Current evidence suggests that patients with co-occurring disorders (presence of both psychiatric and substance use disorders) require a comprehensive, integrated approach that comprises a wide array of services, including pharmacological, behavioral, and psychosocial interventions (Drake et al., 2001; Flynn & Brown, 2008). However, few addiction and mental health programs meet criteria for such capability (McGovern, Lambert-Harris, Gotham, Claus & Xie, 2014). Such a comprehensive approach is difficult to implement due to several barriers within the mental health system, such as lack of integrative treatment for co-occurring disorders, restricted access to medication, scarcity of certified addiction specialists, and diminished funds for long-term monitoring of patients (Marín-Navarrete & Medina-Mora, 2015; Marín-Navarrete& Szerman, 2015; Padwa et al., 2015; Sterling et al., 2011).

The reported rate of co-occurring disorders in individuals receiving residential treatment for substance use disorders ranges between 20–70% (Hasin, Nunes, & Meydan, 2004). However, most of the evidence comes from treatment programs located in high-income countries, particularly in the United States (Arias et al., 2013; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2015; Kessler, 2004; Lev-Ran et al., 2013), limiting the evidence in Mexico to a single study (Marín-Navarrete, Benjet et al., 2013) that found a prevalence rate of 75% for any lifetime psychiatric disorder in residential centers.

In Mexico, specialized treatment services for people with co-occurring disorders are limited within the public health services, while private options are too costly for most people (Marín-Navarrete & Medina-Mora, 2015; Patel et al., 2007). As a result, alternative treatments, such as community-based residential care facilities, are considered instead of psychiatric inpatient care. The main difference between these treatment options is that psychiatric inpatient services are highly standardized, professionalized and publicly-funded or are for-profit health care organizations unaffordable for most of the Mexican population. Conversely, community-based residential care facilities are highly heterogeneous in the provision of services (some offer a vast array of services) and in length of stay (from three weeks to 12-months). These facilities are partially funded by the patients’ families and non-government agencies (Lozano-Verduzco et al., 2016) and are mostly managed and supervised by an individual who has achieved long-term abstinence, commonly lacking professional training in addiction or mental health treatment (Lozano-Verduzco et al., 2016).

Studies have reported that patients undergoing treatment in these facilities in Mexico commonly face overcrowded spaces, violence, unhygienic conditions and care provided by untrained staff who often operate under non-standardized treatment procedures and sub-optimal clinical practices (Harvey-Vera et al., 2016; Lozano-Verduzco et al., 2015; Marín-Navarrete, Eliosa-Hernández et al., 2013). However, this alternative is frequently seen as a means to facilitate community reinsertion of patients who require long-term monitoring and relapse prevention, which might be provided by lay community volunteers under supervision of mental health professionals (Kakuma et al., 2011).

In Mexico there are over 2,000 community-based residential care facilities for substance use that are the main source of treatment for individuals with substance use disorders. However, information on the clinical characteristics of patients undergoing care in these facilities is scarce (CONADIC et al., 2011) and the ability of these facilities to provide care for co-occurring disorders is unknown. This represents a public health concern because such information is crucial to providing appropriate assessment, diagnosis, and treatment, and to identifying staff training and skills requirements to deliver competent care (Kakuma et al., 2011).

The aims of this study were to determine the prevalence of any co-occurring disorders in patients receiving treatment for substance use in these community-based residential centers and to assess whether the presence of co-occurring disorders is associated with greater contact with services and higher severity of substance use, psychiatric symptomatology and other health risks, such as substance use related problems, suicidality, injection drug use, and risky sexual behaviors. We hypothesized that over 50% of the sample would have a co-occurring disorder, and that the presence of a co-occurring disorder would be significantly associated with higher severity of substance use, psychiatric symptoms, and other health risks.

2.0. METHODS

2.1. Setting

The study was conducted at 30 community-based residential care facilities. These facilities were selected from an initial pool of 569 facilities in five Mexican states (Mexico City, State of Mexico, Puebla, Queretaro and Hidalgo) included in a statewide registry provided by their respective addiction councils. The 30 selected facilities were all in compliance with current Mexican regulations for addiction treatment (N0M-028-SSA2–2009), were willing to facilitate the study procedures, and had adequate facilities to ensure patient privacy during study assessments. All data were collected between October, 2013-January, 2014.

2.2. Participants

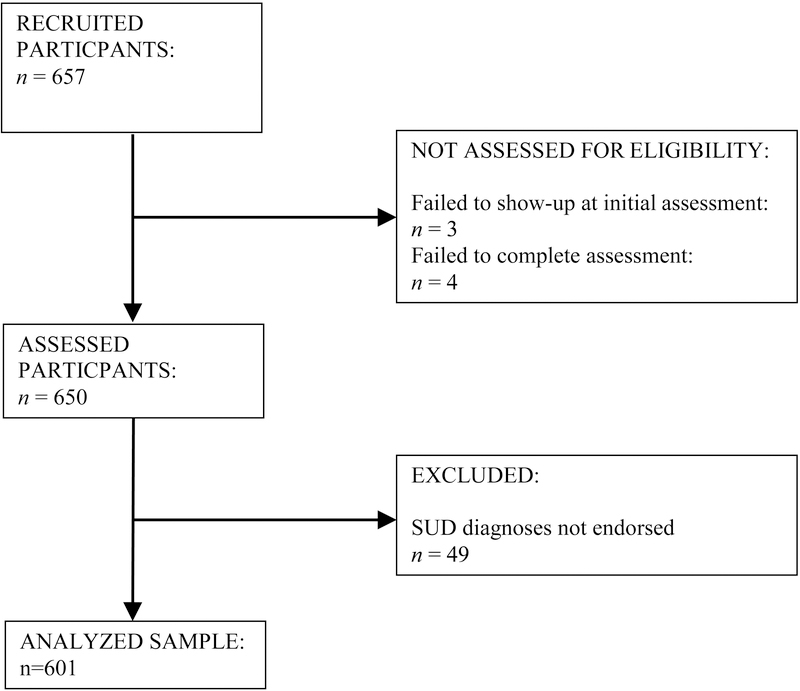

Participants included adults (ages 18–60) admitted to the community-based residential facilities at least a week before recruitment, and who provided written informed consent. Participants who did not endorse DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for any substance use disorder and those who failed to complete the structured interview were excluded from the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Participant flowchart

2.3. Measures

We used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview - fifth version (MINI 5.0) in Spanish to assess psychiatric conditions (Sheehan et al., 1997). The MINI 5.0 is a structured diagnostic interview with adequate inter-rater reliability and diagnostic precision when compared to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Sheehan et al., 1997). For this study, the following psychiatric disorders were assessed: major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, suicide risk, mania/hypomania, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol and drug use disorder, psychotic disorders, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, general anxiety disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

We used the Spanish version of the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90-R) (Derogatis & Cleary, 1977) to measure psychiatric symptom severity. Psychometric properties of the scale are published elsewhere (Cruz-Fuentes et al, 2005). The SCL-90-R items are scored on a 5-point rating scale, and the score of each subscale is the mean of the responses to its items. It is composed of 90 items distributed in nine subscales: somatization, obsessive compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism.

To assess problems related to substance use, we used a Spanish language adaptation of the Short Inventory of Problems-Revised (SIP-R). The SIP-R is a 17-item self-report scale that assesses the frequency of negative consequences of drug and alcohol use in the past three months through a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from “never” to “almost daily.” In addition to a total score, the SIP-R also produces five sub-scale scores (interpersonal, intrapersonal, physical, impulse control and social). Its psychometric properties are reported elsewhere (Kiluk et al., 2013).

Data on other clinical and demographic characteristics (age, education, employment, and marital status) were collected using a demographic interview form specifically designed for this study. This form included a section inquiring about any/all substance use in the previous 30 days as a measure of severity and primary substance of use. Contact with health services was measured with the question: “In your lifetime, which care services have you used to treat alcohol or drug use problems?” Participants were presented the following response options: general practitioner, non-psychiatric specialized physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, school counselor, mental health hotline, religious counselor and traditional healer. Participants were asked about length of stay (in days) and number of times attending the residential treatment center.

Sexual risk behavior and injection drug use were assessed using the HIV Risk-taking Behaviours Scale (HRBS; Darke et al., 1991). In this study, injection drug use, partner concurrence, and inconsistency in condom use with primary and non-primary partners were assessed for the previous 30 days and 12-months. For analytic purposes the items were recoded such that any response other than “Hasn’t hit up” in item 1 was considered injection drug use, any responses other than “none” in items 2–4 indicated needle-sharing, any responses other than “one partner” in item 7 was considered as multiple partners, and any responses other than “always” in items 8–10 and 12 indicated inconsistent condom use.

2.4. Procedures

Participants were recruited through an on-site information session. Interested participants went through an individual informed consent process with an interviewer who provided more detailed information on study assessments, risks, benefits and participant rights. Eligible participants completed all assessments in one or two sessions.

All study procedures were conducted on-site by trained interviewers overseen by a field supervisor. All interviewers and supervisors were staff members from the local institutes and councils against addiction, had experience in addiction treatment and completed at least a bachelor-degree level of education in health sciences. All research team members went through a training process on study assessments and procedures delivered by two clinical experts (a psychiatrist and a psychologist). Training consisted of a two-day centralized workshop, and six post-training webinar sessions, while certification was achieved through a role-playing exercise.

All protocol procedures, informed consent forms, assessment forms, and patient recruitment materials were approved by the Research on Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Psychiatry Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. In compliance with Mexican health laws and good practices for research involving human subjects, for all participants who endorsed psychosis, mania, or suicidality, the research team informed the site director and local health authorities in charge of overseeing the center to ensure patients received adequate treatment.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize variables, using mean and standard deviation for numeric variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Characteristics were compared between participants with substance use disorders only and co-occurring disorders using chi-square (χ2) for categorical and student’s t-test for numerical variables. To answer the first research question, we estimated the proportion of co-occurring psychiatric disorders within the full sample and by group according to whether they endorsed alcohol use disorder only, drug use disorder only or both alcohol and drug use disorders. Univariate χ2 was conducted to determine if there were significant differences in the prevalence of mental disorders by substance use disorder groups. To answer the second question, differences between participants with and without co-occurring psychiatric disorders were estimated using unadjusted and adjusted (controlling for age and sex) regression analysis depending on the assumed distribution of the dependent variables: linear regression for psychiatric symptoms and substance use related problems; binomial logistic regression for injection drug use, inconsistency of condom use, suicide behavior and contact with services; and Poisson regression for days of substance use, length of current residential treatment and number of previous residential treatments. In the regression models a categorical two-level variable was used as the independent variable (co-occurring disorder vs. no co-occurring disorder). Significance was set at p<.05, and all statistical analyses were conducted using R software 3.2.2 (R Development Core Team, 2008).

3.0. RESULTS

A total of 657 participants were recruited and 56 were eliminated (7 did not complete all study assessments and 49 did not endorse criteria for any substance use disorder), leaving a final analytic sample of 601. Participant flowchart throughout the study is presented in Figure 1.

3.1. Demographic characteristics

Almost 90% of participants were male, mean age was 30.2 years (SD=10.9), around half had never been married, and more than 60% had completed elementary school or less. Alcohol was the most commonly reported primary substance of use (45.2%), followed by cocaine (20.7%), inhalants (12.7%), and marijuana (10.4%). Participants with co-occurring disorders tended to be younger, never-married, less educated, less likely to report alcohol as their primary substance of use, and more likely to report daily smoking (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Total (n = 601) |

SUD (n = 225) |

COD (n = 376) |

SUD vs. COD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 30.2 (10.9) | 32.8 (11.5) | 28.7 (10.3) | t(599)=3.62* |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | χ2(1)=.263 | |||

| Female | 61 (10.1) | 21 (9.3) | 40 (10.6) | |

| Male | 540 (89.9) | 204 (90.7) | 336 (89.4) | |

| Marital Status | χ2(2)=11.145* | |||

| Never married | 318 (52.9) | 100 (44.4) | 218 (58.0) | |

| Divorced, Separated, Widowed | 103 (17.1) | 42 (18.7) | 61 (16.2) | |

| Married/Free union | 180 (30.0) | 83 (36.9) | 97 (25.8) | |

| Education | χ2(2)=6.664* | |||

| Elementary school | 385 (64.1) | 130 (57.8) | 255 (67.8) | |

| High school | 161 (26.8) | 73 (32.4) | 88 (23.4) | |

| College | 55 (9.2) | 22 (9.8) | 33 (8.8) | |

| Primary substance | χ2(4)=11.356* | |||

| Alcohol | 271 (45.2) | 121(53.8) | 150 (40.1) | |

| Cannabis | 62 (10.4) | 22 (9.8) | 40 (10.7) | |

| Cocaine | 124 (20.7) | 38 (16.8) | 86 (23.0) | |

| Inhalants | 76 (12.7) | 22 (9.8) | 54 (14.4) | |

| Other | 66 (11.0) | 22 (9.8) | 44 (11.8) | |

| Current cigarette smoker | χ2(1)=12.645* | |||

| Yes | 452 (75.2) | 151 (67.1) | 301 (80.1) | |

| No | 149 (24.8) | 74 (32.9) | 75 (19.9) |

Note. SUD = substance use disorder; COD = co-occurring disorders.

p < .05

3.2. Co-occurring disorders by type of substance use disorder

The prevalence of any psychiatric disorder was 62.6%. Antisocial personality disorder was the most commonly endorsed of all groups and in the overall sample (43.8%), followed by major depressive disorder (30.9%) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (14.6%). Participants with both alcohol and drug use disorders showed significantly higher prevalence for any psychiatric disorder (71.3%, χ2 = 30.63, df = 2, p < .05) when compared to participants with alcohol use disorder only and drug use disorder only. A similar pattern of differences was seen for several individual disorders, including major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, social phobia, psychotic disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Prevalence of all co-occurring disorders comparing participants with alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, and those with co-occurring alcohol and drug use disorders is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Co-occurring disorders (past 30 days)

| Alcohol use disorder (n = 160) |

Drug use disorder (n = 92) |

Alcohol and drug use disorders (n = 349) |

Total (n = 601) |

Statistical differences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | |

| MDD | 36 | 22.5 | 23 | 25.0 | 127 | 36.4 | 186 | 30.9 | χ2(2)=11.70* |

| Dysthymia | 7 | 4.4 | 5 | 5.4 | 21 | 6.0 | 33 | 5.5 | χ2(2)=.57 |

| GAD | 14 | 8.8 | 7 | 7.6 | 39 | 11.2 | 60 | 10.0 | χ2(2)=1.39 |

| PTSD | 8 | 5.0 | 6 | 6.5 | 41 | 11.7 | 55 | 9.2 | χ2(2)=6.91* |

| Social phobia | 5 | 3.1 | 5 | 5.4 | 49 | 14.0 | 59 | 9.8 | χ2(2)=17.12* |

| Bipolar disorder (I, II or any) | 1 | .6 | 3 | 3.3 | 12 | 3.4 | 16 | 2.7 | χ2(2)=3.50 |

| Any psychotic disorder | 7 | 4.4 | 10 | 10.9 | 57 | 16.3 | 74 | 12.3 | χ2(2)=14.73* |

| Anorexia Nervosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | .6 | 2 | .3 | χ2(2)=1.44 |

| Bulimia Nervosa | 2 | 1.3 | 5 | 5.4 | 18 | 5.2 | 25 | 4.2 | χ2(2)=4.64 |

| ADHD | 9 | 5.6 | 13 | 14.1 | 66 | 18.9 | 88 | 14.6 | χ2(2)=15.51* |

| ASPD | 38 | 23.8 | 34 | 37.0 | 191 | 54.7 | 263 | 43.8 | χ2(2)=44.82* |

| Any Disorder | 74 | 46.3 | 53 | 57.6 | 249 | 71.3 | 376 | 62.6 | χ2(2)=30.63* |

Note. MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = general anxiety disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder.

p < .05

3.3. Psychiatric symptoms, days of substance use and substance use related problems

Table 3 shows differences between participants with and without co-occurring disorders in SCL-90-R composite scores and in number of days of substance use. Participants with co-occurring disorders showed significantly greater scores on all composites, as well as in days of alcohol use (aB = .297, SE = .026,p < .05), any drug use (aB = .340, SE = .023,p < .05) and any substance use (aB = .219, SE = .019, p < .05). Participants with co-occurring disorders reported about 3–7 more days of substance use in the past 30 than those with substance use disorder only.

Table 3.

SCL-90-R and past month days of substance use between participants

| SUD | COD | Total | Statistical differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | B (SE) | aB (SE) | |

| SCL-90-R | |||||

| Somatization | .45 (.52) | .95 (.74) | .75 (.71) | .499* (.058) | .504* (.059) |

| Obsessive-compulsive | .68 (.58) | 1.23 (.74) | 1.01 (.73) | .547* (.059) | .533* (.060) |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | .55 (.49) | 1.03 (.75) | .84 (.70) | .482* (.057) | .476* (.058) |

| Depression | .68 (.52) | 1.21 (.77) | 1.00 (.73) | .528* (.060) | .533* (.061) |

| Anxiety | .42 (.46) | .99 (.75) | .76 (.76) | .571* (.057) | .559* (.058) |

| Hostility | .42 (.54) | 1.00 (.84) | .77 (.79) | .574* (.064) | .521* (.064) |

| Phobic anxiety | .23 (.40) | .57 (.68) | .44 (.61) | .334* (.051) | .330* (.052) |

| Paranoid ideation | .50 (.50) | .91 (.72) | .75 (.67) | .417* (.056) | .403* (.057) |

| Psychoticism | .45 (.47) | .93 (.75) | .74 (.69) | .480* (.057) | .471* (.058) |

| Global score | .52 (.42) | 1.02 (.65) | .82 (.62) | .504* (.050) | .496* (.050) |

| Days of substance use | |||||

| Alcohol | 9.97 (9.78) | 12.69 (12.98) | 11.67 (10.69) | .241* (.025) | .297* (.026) |

| Any drug | 10.97 (12.98) | 17.62 (13.33) | 15.13 (13.58) | .473* (.020) | .340* (.023) |

| Any substance | 17.09 (11.14) | 22.06 (10.49) | 20.20 (10.99) | .255* (.019) | .219* (.019) |

Note. SCL-90-R = Symptom Checklist 90-Revised; SUD = substance use disorder; COD = co-occurring disorders; B = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error; aB = adjusted unstandardized regression coefficient, controlling for age and sex.

p < .05

Participants with co-occurring disorders showed higher mean scores on the SIP-R total scale than participants without co-occurring disorders (aB = 4.165, SE = .979, p < .05). These differences were consistently seen on all sub-scales as well, with the greatest difference between groups in the impulsivity (aB = 1.271, SE = .233,p < .05) and physical consequences (aB = .908, SE = .227, p < .05) sub-scales (see Table 4).

Table 4.

SIP-R scores between participants

| SUD | COD | Total | Statistical differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscale | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | B (SE) | aB (SE) |

| Intrapersonal | 5.02 (2.39) | 5.53(2.48) | 5.33 (2.45) | .513* (.215) | .651* (.215) |

| Physical | 4.81 (2.57) | 5.59 (2.55) | 5.28 (2.59) | .782* (.225) | .908* (.227) |

| Social | 5.55 (5.55) | 6.17 (2.54) | 5.93 (2.54) | .620* (.222) | .701* (.224) |

| Impulsivity | 3.60 (2.41) | 4.94 (2.73) | 4.41 (2.69) | 1.335* (.229) | 1.271* (.233) |

| Interpersonal | 5.83 (2.71) | 6.41 (2.66) | 6.18 (2.70) | .577* (.236) | .632* (.240) |

| Total | 24.81 (10.74) | 28.64 (11.13) | 27.12 (11.12) | 3.830* (.966) | 4.165* (.979) |

Note. SIP-R = Short Inventory of Problems-Revised; SUD = substance use disorder; COD = co- occurring disorders; B = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error; aB = adjusted unstandardized regression coefficient, controlling for age and sex.

p < .05

3.4. Injection drug use, sexual risk and suicidal thoughts/behavior

Associations between co-occurring disorders and injection drug use, sexual risk and suicidal behavior in the past 12-months and 30-days are presented in Table 5, along with prevalence of these behaviors for participants both with and without co-occurring disorders. The point prevalence of injection drug use (2.5% in the past 30-days, and 5.3% in the past 12 months) and needle-sharing behavior (1.2% in the past 30-days, and 2.5% in the past 12 months) were very low in the total sample, which may account for the lack of significant differences between groups. Participants with co-occurring disorders reported more sexual risk behaviors than those without co-occurring disorders, with significantly greater odds of multiple partners in the past 30 days (aOR = 1.95, 95% CI [1.07, 3.75];p < .05); and inconsistency in condom use with nonprimary partner in the past 30 days (aOR = 2.00, 95% CI [1.01, 4.26], p < .05) and in the past 12 months (aOR = 2.00, 95% CI [1.35, 2.98],p < .05), and in anal sex in the past 12 months (aOR = 2.13, 95% CI [1.40, 3.28],p < .05).

Table 5.

Injection drug use, sexual risk and suicide behavior between participants

| SUD | COD | Total | Statistical differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | B [95% CI] | aOR [95% CI] | |

| Injection drug use | |||||

| Use past 30 days | 5 (2.2) | 10 (2.7) | 15 (2.5) | 1.20 [.40, 3.56] | .88 [.29, 2.93] |

| Use past 12 mos | 8 (3.6) | 24 (6.4) | 32 (5.3) | 1.84 [.81, 4.19] | 1.59 [.71, 3.90] |

| Needle sharing past 30 days | 2 (.9) | 5 (1.3) | 7 (1.2) | 1.50 [.28, 7.81] | 1.01 [.20, 7.37] |

| Needle sharing past 12 mos | 4 (1.8) | 11 (2.9) | 15 (2.5) | 1.66 [.52, 5.29] | 1.43 [.47, 5.31] |

| Partner concurrence | |||||

| Past 30 days | 15 (6.7) | 44 (11.7) | 59 (9.8) | 2.06 [1.11, 3.80]* | 1.95 [1.07, 3.75]* |

| Past 12 mos | 113 (51.6) | 210 (63.1) | 323 (58.5) | 1.60 [1.13, 2.26]* | 1.30 [.90, 1.89] |

| Inconsistency in condom use | |||||

| Primary partner past 30 days | 41 (18.7) | 70 (21.0) | 111 (20.1) | 1.15 [.74, 1.76] | 1.04 [.67, 1.62] |

| Primary partner past 12 mos | 135 (61.6) | 224 (67.1) | 359 (64.9) | 1.26 [.88, 1.80] | 1.22 [.85, 1.76] |

| Non-primary partner past 30 days | 11 (5.0) | 34 (10.2) | 45 (8.1) | 2.14 [1.06, 4.32]* | 2.00 [1.01, 4.26]* |

| Non-primary partner past 12 mos | 50 (22.8) | 135 (40.4) | 185 (33.5) | 2.29 [1.56, 3.36]* | 2.00 [1.35, 2.98]* |

| In sex exchange past 30 daysa | 4 (1.8) | 14 (4.2) | 18 (3.3) | 2.35 [.76, 7.24] | 2.34 [.81, 8.46] |

| In sex exchange past 12 mosa | 14 (6.4) | 38 (11.4) | 52 (9.4) | 1.88 [.99, 3.55] | 1.84 [.98, 3.63] |

| In anal sex past 30 days | 12 (5.5) | 33 (9.9) | 45 (8.1) | 1.89 [.95, 3.74] | 1.66 [.85, 3.46] |

| In anal sex past 12 mos | 39 (17.8) | 111 (33.3) | 150 (27.2) | 2.30 [1.52, 3.49]* | 2.13[1.40, 3.28]* |

| Suicidal behavior | |||||

| Thoughts past 30 days | 9 (4.0) | 68 (18.1) | 77 (12.8) | 5.29 [2.58, 10.84]* | 5.07 [2.58, 11.17]* |

| Planning past 30 days | 7 (3.1) | 56 (14.9) | 63 (10.5) | 5.45 [2.43, 12.18]* | 5.17 [2.44, 12.73]* |

| Attempts past 30 days | 2 (.9) | 50 (5.3) | 22 (3.7) | 6.26 [1.45, 27.05]* | 6.43 [1.83, 40.78]* |

| Attempts lifetime | 41 (18.2) | 177 (47.1) | 218 (36.3) | 3.99 [2.69, 5.92]* | 3.91 [2.62, 5.93]* |

Note: SUD = substance use disorder; COD = co-occurring disorders; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; aOR = adjusted odds ratio, controlling for age and sex.

Exchange of sex for money or drugs

p < .05

A prevalence of 3.7% was observed for suicide attempt in the past 30 days and 36.3% for lifetime suicide attempts in the whole sample. Participants with co-occurring disorders showed significantly greater odds of suicidal thoughts (aOR = 5.07, 95% CI [2.58, 11.17],p < .05), planning (aOR = 5.17, 95% CI [2.44, 12.73],p < .05) and attempts (aOR = 6.43, 95% CI [1.83, 40.78], p < .05) in the past 30 days, compared to participants without co-occurring disorders.

3.5. Contact with services

Table 6 presents the frequencies and odds ratios for contact with various services between groups. More than half of the sample (56.6%) reported having contacted any professional service for addiction or mental health problems in their lifetime, while 44.9% reported contact with a psychologist and 37.3% with alternative care services. Participants with co-occurring disorders showed significantly greater probabilities of contact with all treatment services than those with substance use disorders only. They also had significantly more days in current residential treatment (aB = .03, SE = .01 p < .05) and a higher number of previous residential treatments (aB = .40, SE = .04, p < .05).

Table 6.

Contact with services

| SUD | COD | Total | Statistical differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | OR [95% CI] | aOR [95% CI] | |

| General practitioner | 40 (17.8) | 89 (23.7) | 129 (21.5) | 1.43 [.946, 2.17] | 1.62 [1.06, 2.52]* |

| Physician (no psychiatric specialty) | 9 (4.0) | 29 (7.7) | 38 (6.3) | 2.00 [.93, 4.31] | 2.33 [1.10, 5.46]* |

| Psychiatrist | 47 (20.9) | 115 (30.6) | 162 (27.0) | 1.66 [1.13, 2.46]* | 1.82 [1.22, 2.74]* |

| Psychologist | 86 (38.2) | 184 (48.9) | 270 (44.9) | 1.54 [1.10, 2.16]* | 1.43 [1.01, 2.02]* |

| Any professional service | 108 (48.0) | 232 (61.7) | 340 (56.6) | 1.74 [1.25, 2.43]* | 1.77 [1.26, 2.49]* |

| Any alternative service a | 59 (26.2) | 165 (43.9) | 224 (37.3) | 2.20 [1.30, 2.14]* | 2.45 [1.69, 3.57]* |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | B (SE) | aB (SE) | |

| Residential treatment (lifetime) | |||||

| Total days | 65.04 (62.49) | 67.36 (68.43) | 66.49(66.22) | .03 (.01)* | .03 (.01)* |

| Number of treatment stays | 3.39 (6.74) | 4.66 (8.20) | 4.19 (7.70) | .31 (.04)* | .40 (.04)* |

Note: SUD = substance use disorder; COD = co-occurring disorders; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; aOR = adjusted odds ratio, controlling for age and sex, B = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error; aB = adjusted unstandardized regression coefficient, controlling for age and sex.

Including religious counselor and traditional healer.

p < .05

4.0. DISCUSSION

This study sought to examine the prevalence of co-occurring disorders in a sample of patients receiving treatment for substance use disorders in community-based residential care facilities, and to assess the association of co-occurring disorders with severity of substance use, psychiatric symptomatology, and other health risks.

The results of this study indicate that people receiving services in these community-based residential facilities show a high prevalence of co-occurring disorders (63%) and are mostly affected by polysubstance use disorders (58%). Participants with co-occurring disorders displayed differences in the severity of psychiatric symptoms, substance-use related problems, days of substance use, risky sexual behavior, suicidal thoughts and behavior, and contact with services when compared to those endorsing only substance use disorders.

These results are in line with previous findings that reported high prevalence of co-occurring disorders among clinical populations in diverse settings from outpatient (Arias et al., 2013; Roncero et al., 2015; Urbanoski et al., 2015) to residential (Hasin, Nunes, & Meydan, 2004) substance use disorders treatment. Previous studies also documented differential clinical outcomes among patients with co-occurring disorders (Torrens-Melich, 2008) with an increased level of severity and overall impairment (Marín-Navarrete& Szerman, 2015).

Notably, current and lifetime suicide attempt rates (3.7% and 36.3% respectively) reported by participants with co-occurring disorders in our study are substantially higher than those in the general population in Mexico (2.7% lifetime attempt) (Borges et al., 2007). This suggests that substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders may have a synergist effect, increasing the probability of suicide attempt when both conditions are present. This finding is in accordance with studies reporting disproportionally higher suicidal behavior in comorbid major depression and alcoholism (Cornelius et al., 1995; Salloum et al., 1995) emphasizing the need for developing and implementing on-site suicide behavior screening and interventions.

Another domain which has been scarcely studied in individuals with co-occurring disorders is their proneness to risky sexual behaviors, as previous evidence has been inconclusive on this subject (Meade, 2006). Our findings suggest that participants with co-occurring disorders displayed higher likelihood of partner concurrence and inconsistency in condom use. Increases in on-site monitoring of sexually transmitted infections and in promoting sexual health counseling in this population are substantially needed.

The results of this study are supportive of previous evidence indicating that patients with co-occurring disorders require specialized, integrated assessment and treatment (Minkoff et al., 2004) to improve outcomes and overall treatment costs. Although previous studies of community-based residential care facilities’ structure, services, and patient experiences (Lozano-Verduzco et al., 2015; Marín-Navarrete, Eliosa-Hernández et al., 2013) clearly suggested that these facilities failed to provide integrated assessment and treatment for this population, the impact on outcomes in patients with co-occurring disorders is still unknown. While these facilities are the main source of treatment for patients with severe substance use disorders in Mexico (Marín-Navarrete & Medina-Mora, 2015), care for co-occurring disorders in these setting would be significantly enhanced by the development of treatment standards that focus on integration of care for co-occurring disorders and on monitoring treatment outcomes and costs in order to address this problem.

This study has several limitations. First, the sampling method was not probabilistic; therefore these results are not representative of all facilities across the country. This is noteworthy given the heterogeneity of the geography of substance use in Mexico (e.g., higher injection drug use in the northern region and higher marijuana use in México City). In addition, the number of women enrolled in the study (10% of the sample) limits the statistical power to detect between-sex differences. This becomes a main concern in the study of co-occurring disorders as the prevalence, types and outcomes are highly differentiated by sex (Choi et al., 2015).

This study is unique in terms of evaluating the frequency and impact of co-occurring disorders in a major sector of substance use services across Mexico. An important strength of this study is the wide array of clinical indicators, in addition to co-occurring disorders diagnosis, in a clinical population in one of the most utilized, and less studied treatment alternatives. This is one of few multi-center clinical studies of its type to be conducted outside high-income countries.

5.0. CONCLUSIONS

Despite the multiple limitations of community-based residential care facilities, they may have potential benefits in Mexico, since they respond to basic treatment demands of patients with substance use disorders at a low cost, and show accessibility in areas where the supply of public services is insufficient. Future studies should aim to assess the range of capabilities of these centers.

The results shown that people using these facilities are exposed to multiple behavioral risks as well. To provide an effective care for these patients, simple peer support is not adequate. An integrative model of care along with well-trained and qualified health professionals is highly required.

These findings are in concordance with previous international studies on the high prevalence of co-occurring disorders among those in substance use treatment and the clinical impact of such comorbidity. Co-occurring disorders are not the exception but the rule. These results underscore the need for a consensus between representatives of the clinical, academic and public health policy fields, to address the complexity of co-occurring disorders and create effective strategies in funding, training, assessment, diagnosis, placement, and treatment in community-based residential care facilities for substance use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A special acknowledgment for their institutional support in this study: National Institute on Drug Abuse – Clinical Trials Network (NIDA-CTN), Consejo Nacional Contra las Adicciones (CONADIC-México), Instituto para la Atención y Prevención de las Adicciones en la Ciudad de México (IAPA), Instituto Mexiquense Contra las Adicciones (IMCA), Consejo Estatal Contra las Adicciones de Puebla (CECA-P), Consejo Estatal Contra las Adicciones de Hidalgo (CECA-H), Consejo Estatal Contra las Adicciones de Querétaro (CECA-Q). We also wish to thank David Sheehan M.D., for allowing the use of the Spanish-language adaptation of the 5th version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview in Spanish; and Aldebarán Toledo-Fernández MSc, for his comments to improve this paper.

FUNDING SOURCES

This study is part of the project “Development of a Clinical Trial Network on Addiction and Mental Health in Mexico ” funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of State (Grants No. SINLEC11GR0015/A001/A002) awarded to the Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz in Mexico. The U.S. Department of State had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit this paper for publication.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

REFERENCES

- Arias F, Szerman N, Vega P, Mesias B, Basurte I, Morant C, & Babín F. (2013). Estudio Madrid sobre prevalencia y características de los pacientes con patología dual en tratamiento en las redes de salud mental y de atención al drogodependiente. [Madrid Study On The Prevalence And Characteristics Of Outpatients With Dual Pathology In Community Mental Health And Substance Misuse Services]. Adicciones, 25(2), 118127. doi: 10.20882/adicciones.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Nock MK, Medina-Mora ME, Benjet C, Lara C, Chiu WT, & Kessler R. (2007). The epidemiology suicide of suicide-related outcomes in Mexico. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(6), 627–640. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.6.627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Adams SM, Morse SA, & MacMaster S. (2015). Gender differences in treatment retention among individuals with co-occurring substance abuse and mental health disorders. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(5), 653–663. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.997828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional Contra las Adicciones (CONADIC), Centro Nacional para la Prevención y el Control de las Adicciones (CENADIC), & Comisión Interamericana para el Control del Abuso de Drogas (CICAD-OEA). (2011). Diagnóstico nacional de servicios de tratamiento residencial de las adicciones: perfil del recurso humano vinculado al tratamiento de personas con problemas relacionados al abuso y dependencia a drogas y perfil del usuario [National Diagnosis Of The Residential Treatment Services For Addiction: Human Resources Proflied Linked To Treatment For People With Problems Related To The Abuse And Dependency Of Drugs And Users Profile ]. México: CONADIC [ISBN 978–607-95766–0-8]. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Mezzich J, Cornelius MD, Fabrega H Jr, Ehler JG, ... & Mann JJ (1995). Disproportionate suicidality in patients with comorbid major depression and alcoholism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152(3), 358–364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Fuentes CS, Lopez-Bello L, Blas-Gracia C, Gonzalez-Macias L, & Chavez-Balderas RA (2005). Datos sobre la validez y la confiabilidad de la Symptom Check List (SCL-90) en una muestra de sujetos mexicanos [Data about validity and reliability of the Symptom Check List 90 (SCL 90) in a Mexican population sample.]. Salud Mental, 28(1), 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Hall W, Heather N, & Ward J. (2001). The reliability and validity of a scale to measure HIV risk-taking behavior among intravenous drug users. Aids, 5(2), 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR & Cleary PA (1977). Confirmation of the dimensional structure of the scl-90: A study in construct validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33(4), 981–989. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, Carey KB, Minkoff K, Kola L, ... & Rickards L. (2001). Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 52, 469–476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2015). Comorbidity of substance use and mental disorders in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, & Brown BS (2008). Co-occurring disorders in substance abuse treatment:Issues and prospects. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 34(1), 36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey-Vera AT, Gonzalez-Zuniga P, Vargas-Ojeda AC, Medina-Mora ME, Magis-Rodriguez CL, Wagner K, ... & Werb D. (2016). Risk of violence in drug rehabilitation centers: Perceptions of people who inject drugs in Tijuana, Mexico. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 11(1), 1 – 9. doi: 10.1186/s3011-015-0044-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Nunes E, & Meydan J. (2004). Comorbidity of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric disorders: Epidemiology In Kranzler HR, & Tinsley JA (2nd Ed.), Dual diagnosis and psychiatric treatment: Substance abuse and comorbid disorders. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker. [Google Scholar]

- Kakuma R, Minas H, van Ginneken N, Dal Poz MR, Desiraju K, Morris JE, ... & Scheffler RM (2011). Human resources for mental health care: Current situation and strategies for action. The Lancet, 378(9803), 1654–1663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61093-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC (2004). The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biological Psychiatry, 56(10), 730737. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Dreifuss J, Weiss RD, Horigian VE, & Carroll KM (2013) Psychometric properties of a Spanish-language version of the Short Inventory of Problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(3), 893–900. doi: 10.1037/a0032805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Ran S, Imtiaz S, Rehm J, & Le Foll B. (2013). Exploring the association between lifetime prevalence of mental illness and transition from substance use to substance use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). The American Journal on Addictions, 22(2), 93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00304.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Verduzco I, Marín-Navarrete R, Romero-Mendoza M, & Tena-Suck A. (2016). Experiences of power and violence in Mexican men attending mutual-aid residential centers for addiction treatment. American Journal of Men’s Health. 10(3), 237–249. doi: 10.1177/1557988314565812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Navarrete R, & Medina-Mora ME (2015). Comorbilidades en los Trastornos por Consumo de Sustancias: Un desafío para los servicios de salud en México En: Medina-Mora ME(Ed.): La depresión y otros trastornos psiquiátricos. (pp. 39–58). México: Academia Nacional de Medicina de México A. C. [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Navarrete R, & Szerman N. (2015). Repensando el concepto de adicciones: pasos hacía la patología dual [Rethinking the concept of addictions: steps towards dual pathology]. Salud Mental, 38(6), 395–396. doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2015.060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Navarrete R, Benjet C, Borges G, Eliosa-Hernández A, Nanni-Alvarado R, Ayala-Ledesma M, ... & Medina-Mora ME (2013). Comorbilidad de los trastornos por consumo de sustancias con otros trastornos psiquiátricos en Centros Residenciales de Ayuda-Mutua para la Atención de las Adicciones [Comorbidity of substance use disorders with other psychiatric disorders in Mutual-Aid Residential Treatment Centers]. Salud Mental, 36(6), 471–479. doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2013.057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Navarrete R, Eliosa-Hernández A, Lozano-Verduzco I, Turnbull B, Fernández de la Fuente C, & Tena-Suck A. (2013). Estudio sobre la experiencia de hombres atendidos en centros residenciales de ayuda mutua para la atención de las adicciones [Study on the experience of men treated in residential substance abuse support centers]. Salud Mental, 36(5), 393–402. doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2013.049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS (2006). Sexual risk behavior among persons dually diagnosed with severe mental illness and substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(2), 147157. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkoff K, Zweben J, Rosenthal R, & Ries R. (2004). Development of service intensity criteria and program categories for individuals with co-occurring disorders. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 22(S1), 113–129. doi: 10.1300/J069v22S01_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padwa H, Guerrero EG, Braslow JT, & Fenwick KM (2015). Barriers to serving clients with co-occurring disorders in a transformed mental health system. Psychiatric Services, 66(5), 547–550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, ... & van Ommeren M. (2007). Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 370(9591), 991–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2008). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Viena: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [ISBN 3–900051-07–0] Retrieved from: http://www.r-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Roncero C, Ortega L, Perez-Pazos J, Lligona A, Abad AC, Gual A, ... & Daigre C. (2015). Psychiatric comorbidity in treatment-seeking alcohol dependence patients with and without ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. doi: 10.1177/1087054715598841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum IM, Mezzich JE, Cornelius J, Day NL, Daley D , & Kirisci L. (1995). Clinical profile of comorbid major depression and alcohol use disorders in an initial psychiatric evaluation. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 36(4), 260–6. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(95)90070-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, ... & Dunbar GC (1997). The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. European Psychiatry, 12(5), 232–241. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83297-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling S, Chi F, & Hinman A. (2011). Integrating care for people with co-occurring alcohol and other drug, medical, and mental health conditions. Alcohol Research & Health, 33(4), 338–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrens-Melich M. (2008). Patología dual: situación actual y retos de futuro [Dual diagnosis]. Adicciones, 20(4), 0315–320. doi: 10.20882/adicciones.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanoski K, Kenaszchuk C, Veldhuizen S, & Rush B. (2015). The clustering of psychopathology among adults seeking treatment for alcohol and drug addiction. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 49(1), 21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]