Abstract

Background

Polymorphisms in the interleukin-10 (IL-10) gene have been studied in various ethnic groups for possible association with Behçet’s disease (BD). This study aimed to perform a meta-analysis of eligible studies to calculate the association of IL-10 polymorphisms with BD.

A systematic literature search was carried out in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus databases to identify relevant publications, and extracted the respective results. Pooled odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to evaluate the power of association with a random-effects model.

Results

A total of 19 articles, consisting of 10,626 patients and 13,592 controls were included in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis revealed significant associations in allelic and genotypic test models of − 819 (C vs. T: OR = 0.691, P < 0.001; CC vs. TT: OR = 0.466, P < 0.001; CC + CT vs. TT: OR = 0.692, P < 0.001; and CC vs. CT + TT: OR = 0.557, P < 0.001), − 592 (C vs. A: OR = 0.779, P = 0.002; CC + AA vs. AA: OR = 0.713, P = 0.021; and CA vs. AA: OR = 0.716, P = 0.016), rs1518111 (G vs. A: OR = 0.738, P < 0.001; GG vs. AA: OR = 0.570, P < 0.001; GG + AG vs. AA: OR = 0.697, P < 0.001; GG vs. GA + AA: OR = 0.701, P < 0.001; and AG vs. GG: OR = 0.786, P = 0.004) and rs1554286 (C vs. T: OR = 0.582, P < 0.001; CC vs. TT: OR = 0.508, P < 0.001; CC + CT vs. TT: OR = 0.605, P < 0.001; CC vs. CT + TT: OR = 0.665, P = 0.012; and CT vs. TT: OR = 0.646, P = 0.001). However, we failed to find any association between − 1082 polymorphism and susceptibility of BD.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrated that the interleukin-10 -819, − 596, rs1518111 and rs1554286 polymorphisms could be responsible against BD susceptibility, and should probably be regarded as a protective factor for Behçet’s disease.

Keywords: Behçet’s disease, Interleukin-10, Polymorphism, Meta-analysis

Background

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a chronic remitting systemic vasculitis of unrevealed etiology [1]. BD is heterogeneous in onset [2] that its common clinical manifestations are orogenital ulcers, skin lesions, and uveitis [3]. BD is frequently observed in the Far East and the Middle East; however, it has distributed along the Old Silk Route due to immigration [1, 4–6]. Although the exact cause of Behçet’s disease is mostly indefinite, it is believed that the pivotal pathophysiologic event is an inflammatory reaction to environmental factors in a genetically predisposed host and presence of epigenetic changes [7–11]. Research has evidenced that various cytokine networks play a crucial role in the determination of the disease onset, course of the disease, and outcome [12]. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) [Gene ID: 3586] is a multifunctional cytokine that acts upon other cytokines’ signaling pathways [13]. IL-10 is a Type II cytokine in a family, including IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-26, and IL-29 [14]. IL-10 is expressed mostly by activated monocytes/macrophages, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, mast cells, T lymphocytes (mainly Th2 subsets), and B lymphocytes [15].

This immuno-regulatory cytokine was demonstrated to have an imperative cytokine-suppressing role in the autoimmunity and inflammatory responses as a result of its ability to the downregulate antigen presentation and macrophage activation [16–20]. The abundant evidence has revealed that low IL-10 expression is involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases such as BD [21]. Furthermore, polymorphisms in multiple immuno-regulatory genes have indicated as a risk predisposition for the developing of BD owing to their effect on the cytokine production [22]. The human IL-10 gene maps to 1q31–32 and contains five exons and four introns. The IL-10 promoter is highly polymorphic and these single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) appear to be correlated to the expression level of IL-10. Three frequently investigated SNPs of IL-10 gene are − 1082 A to G (rs1800896) -lies within a putative Ets transcription factor binding site-, − 819 T to C (rs1800871) -placed within a putative positive regulatory region-, and − 592 A to C (rs1800872) -is located within a putative STAT-3 binding site and negative regulatory region- polymorphisms [23, 24]. Rs1518111 (2195 A to G) which is in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with rs1800896 and rs1554286 (2607 T to C) that is in a strong LD with rs1800571 are the intronic variant of second and third exons [25, 26].

Considering the role of IL-10 in BD and the correlation between the IL-10 gene polymorphisms and IL-10 production, several studies have been carried out to investigate the association of the IL-10 gene polymorphisms with the BD susceptibility. However, contradictory reported results and/or small sample size could lead to low statistical power and false-positive results. Therefore, in order to deal with these ambiguities, and potential biases, such as publication bias and providing increased statistical power, we turned to meta-analysis. In the present study, a meta-analysis of all available published studies was carried out to clarify the association between the IL-10 gene polymorphisms and the BD susceptibility.

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

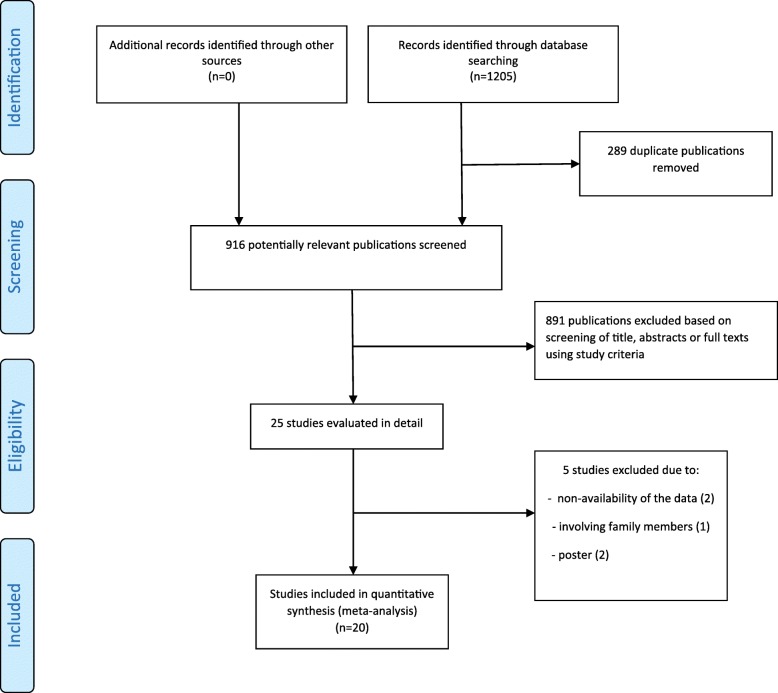

The literature search filtered 2390 English and Persian-language potential articles related to the IL-10 polymorphisms and BD. After the removal of duplicates, other publications were reviewed based on the titles and abstracts. In the end, 24 eligible studies were selected with a full-text review where 5 studies were eliminated (two studies due to non-availability of the data, even no responses could be gotten after having sought the relevant data via email contacts, two were posters and one study was involving family members). A flowchart of the study selection process and its results is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of studies for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis

We conduct the meta-analysis, involving 10,626 cases and 13,592 controls. Of the 19 articles, studies including different subpopulations were considered as separate studies. Consequently, these groups were independently analyzed. Ten studies reported on -1082G/A, nineteen studies on -819C/T, thirteen studies on −592C/A, thirteen studies on rs1518111G/A and three studies on rs1554286C/T. The baseline characteristics of the eligible studies are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author(year) | Ethnicity | Sample size case/control | Mean-age | Genotyping methods | Studied polymorphism | HWE Pvalue (control) |

ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | |||||||

| Baris S(2016) | Turkish | 71/70 | 37.8 ± 1.0 | – | PCR-RFLP | rs1800896 | – | 27 |

| Hu J. stage I(2015) | Chinese Han | 300/350 | 33.60 ± 8.78 | 39.66 ± 11.19 | PCR-RFLP | rs1800896, rs1800872, rs1554286 | p > 0.05 | 28 |

| Hu J. stage II(2015) | Chinese Han | 418/1403 | 33.60 ± 8.78 | 39.66 ± 11.19 | PCR-RFLP | rs1800871 | p > 0.05 | 28 |

| Al-Okaily F(2015) | Saudi | 61/211 | 37.87 ± 12.5 | 36 ± 10 | PCR-ARMS | rs1800896, rs1800871, rs1800872 | – | 29 |

| Talaat R. M(2014) | Egyptian | 87/97 | 34.37 ± 10.36 | – | PCR-SSP | rs1800896, rs1800871 | p > 0.05 | 30 |

| Xavier J. M(2012) | Iranian | 973/637 | 39.1 ± 11.0 | 42.0 ± 11.6 | Sequenom iPlex assay | rs1800896, rs1518111, rs1554286 | P > 0.01 | 26 |

| Shahram F(2011) | Iranian | 150/140 | – | – | PCR-SSP | rs1800896, rs1800871, rs1800872 | p > 0.05 | 31 |

| Ates O(2010) | Turkish | 102/102 | 37.2 ± 8.4 | 52 ± 7 | PCR-ARMS | rs1800896, rs1800871, rs1800872 | – | 32 |

| Dilek K(2009) | Turkish | 97/127 | – | – | PCR-SSP | rs1800896, rs1800871, rs1800872 | p > 0.05 | 33 |

| Wallace GR(2007) | UK | 63/182 | – | – | PCR-SSP | rs1800896, rs1800871 | p > 0.05 | 34 |

| Wallace GR(2007) | ME | 115/113 | – | – | PCR-SSP | rs1800896, rs1800871 | p > 0.05 | 34 |

| Kramer M(2018) | Turkish | 64/68 | – | – | Sanger technique | rs1800871, rs1800872, rs1518111 | – | 35 |

| Kramer M(2018) | Israeli | 25/20 | – | – | Sanger technique | rs1800871, rs1800872, rs1518111 | – | 35 |

| Yu H(2017) | Chinese Han | 1206/2475 | 34.86 ± 9.9 | 35.46 ± 10.3 | Sequenom Mass Array | rs1800871, rs1554286 | – | 36 |

| Carapito R(2015) | Iranian | 552/417 | – | – | Taqman | rs1800871, rs1518111 | – | 37 |

| Wu Z(2014) | Chinese | 407/679 | 38.02 ± 12.44 | 38.81 ± 10.45 | Sequenom Mass Array | rs1800871, rs1518111 | p > 0.05 | 38 |

| Khaib Dit Naib O(2013) | Western Algeria | 51/96 | 26 ± 11 | – | Direct sequencing | rs1800871, rs1800872 | – | 39 |

| Kirino Y(2013) | Turkish | 1209/1278 | – | – | GWAS | rs1800871, rs1518111 | P < 0.0001 | 40 |

| Mizuki N(2010) | Japanese | 611/737 | – | – | GWAS | rs1800871, rs1800872 | P < 0.001 | 7 |

| Mizuki N(2010) | Korean | 124/140 | – | – | GWAS | rs1800871, rs1800872 | P < 0.001 | 7 |

| Mizuki N(2010) | Turkish | 1215/1279 | – | – | GWAS | rs1800871, rs1800872 | P < 0.001 | 7 |

| Afkari B(2018) | Iranian | 47/58 | 38.02 ± 10.25 | 37.4 ± 8.5 | PCR-RFLP | rs1800872 | p > 0.05 | 41 |

| Montes-Cano MA(2013) | Spanish | 304/313 | 38.7 ± 13.8 | – | Taqman | rs1800872 | p > 0.05 | 42 |

| Remmers EF(2010) | Discovery-Turkish | 1161/1221 | – | – | GWAS | rs1518111 | p > 0.00001 | 8 |

| Remmers EF(2010) | Rplication-Turkish | 110/224 | – | – | GWAS | rs1518111 | p > 0.00001 | 8 |

| Remmers EF(2010) | Replication-Middle Eastern Arab | 188/163 | – | – | GWAS | rs1518111 | p > 0.00001 | 8 |

| Remmers EF(2010) | Replication-Greek | 107/84 | – | – | GWAS | rs1518111 | p > 0.00001 | 8 |

| Remmers EF(2010) | Replication-UK Caucasian | 120/119 | – | – | GWAS | rs1518111 | p > 0.00001 | 8 |

| Remmers EF(2010) | Replication-Korean | 77/52 | – | – | GWAS | rs1518111 | p > 0.00001 | 8 |

| Remmers EF(2010) | Replication-Japanese | 611/737 | – | – | GWAS | rs1518111 | p > 0.00001 | 8 |

Association between rs1800896 polymorphism and risk of BD

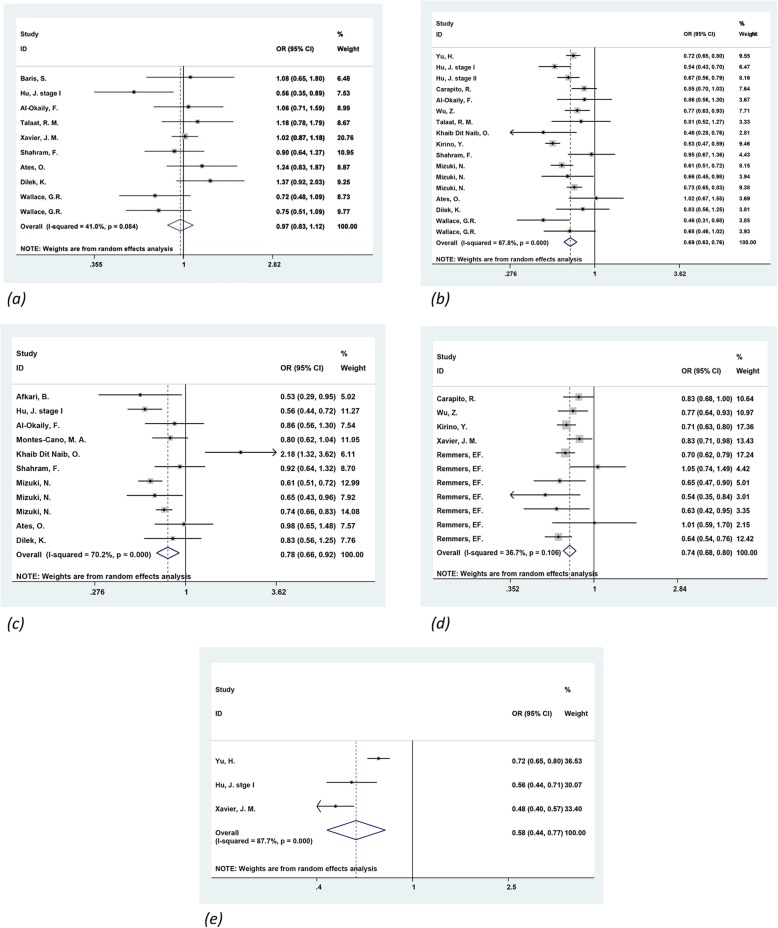

Based on ten studies [26–34], including 1970 cases and 1930 controls, the association between IL-10 -1082G/A polymorphism and BD susceptibility was examined. The combined results showed that considering all the studies, the comparisons of allele and genotypes failed to detect any statistical association under the random-effects model (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of the association between IL-10 polymorphisms and BD risk

| polymorphism | No. of studies | Comparison | Test of association | Test of heterogeneity | Egger’s test (P) | Metareg’s test (P) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | P- value | I2 (%) | Q test | |||||

| rs1800896 A/G | 10 | GG vs. AA | 0.925 (0.684–1.251) | 0.613 | 0.266 | 19.9 | 9.98 | 0.746 | 0.689 |

| GG + GA vs. AA | 0.936 (0.733–1.195) | 0.596 | 0.020 | 56/0 | 18.20 | 0.836 | 0.866 | ||

| GG vs. GA + AA | 0.975 (0.660–1.441) | 0.900 | 0.025 | 54.4 | 17.55 | 0.619 | 0.640 | ||

| AG vs. AA | 0.945 (0.717–1.245) | 0.687 | 0.007 | 62.2 | 21.17 | 0.822 | 0.870 | ||

| G vs. A | 0.965 (0.831–1.120) | 0.640 | 0.084 | 41.0 | 15.25 | 0.816 | 0.807 | ||

| rs1800871 T/C | 19 | CC vs. TT | 0.466 (0.368–0.589) | 0.000 | 0.003 | 57.4 | 32.88 | 0.081 | 0.347 |

| CC + CT vs. TT | 0.692 (0.584–0.820) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 66.1 | 41.33 | 0.842 | 0.674 | ||

| CC vs. CT + TT | 0.557 (0.405–0.767) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 86.6 | 119.02 | 0.032 | 0.123 | ||

| CT vs. TT | 0.842 (0.572–1.240) | 0.384 | 0.000 | 93.7 | 220.52 | 0.542 | 0.883 | ||

| C vs. T | 0.691 (0.626–0.762) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 67.8 | 49.73 | 0.363 | 0.493 | ||

| rs1800872 A/C | 13 | CC vs. AA | 0.723 (0.440–1.186) | 0.199 | 0.000 | 72.4 | 32.63 | 0.161 | 0.360 |

| CC + CA vs. AA | 0.713 (0.535–0.951) | 0.021 | 0.004 | 62.4 | 23.94 | 0.116 | 0.276 | ||

| CC vs. CA + AA | 0.776 (0.583–1.032) | 0.082 | 0.004 | 60.3 | 27.71 | 0.210 | 0.367 | ||

| CA vs. AA | 0.716 (0.546–0.940) | 0.016 | 0.024 | 53.0 | 19.13 | 0.101 | 0.313 | ||

| C vs. A | 0.779 (0.662–0.915) | 0.002 | 0.000 | 70.2 | 33.59 | 0.194 | 0.423 | ||

| rs1518111 A/G | 13 | GG vs. AA | 0.570 (0.471–0.690) | 0.000 | 0.459 | 0.0 | 1.56 | 0.622 | 0.741 |

| GG + GA vs. AA | 0.697)0.596–0.814) | 0.000 | 0.393 | 0.0 | 1.87 | 0.684 | 0.533 | ||

| GG vs. GA + AA | 0.701 (0.623–0.790) | 0.000 | 0.505 | 0.0 | 3.32 | 0.558 | 0.967 | ||

| AG vs. AA | 0.786 (0.667–0.927) | 0.004 | 0.723 | 0.0 | 0.65 | 0.604 | 0.645 | ||

| G vs. A | 0.738 (0.681–0.800) | 0.000 | 0.106 | 36.7 | 15.79 | 0.500 | 0.352 | ||

| rs1554286 T/C | 3 | CC vs. TT | 0.508 (0.372–0.694) | 0.000 | 0.198 | 38.2 | 3.23 | 0.795 | 0.868 |

| CC + CT vs. TT | 0.605)0.467–0.785( | 0.000 | 0.087 | 59.1 | 4.89 | 0.626 | 0.466 | ||

| CC vs. CT + TT | 0.665)0.484–0.916( | 0.012 | 0.041 | 68.7 | 6.40 | 0.487 | 0.893 | ||

| CT vs. TT | 0.646 (0.502–0.832) | 0.001 | 0.115 | 53.8 | 4.33 | 0.656 | 0.506 | ||

| C vs. T | 0.582 (0.440–0.770) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 87.7 | 16.23 | 0.384 | 0.265 | ||

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the association of IL-10 polymorphisms with BD. A random-effects model for the OR with 95% CI was used to detect an association between IL-10 polymorphisms with BD. (a) rs1800896 (b) rs1800871 (c) rs1800872 (d) rs1518111 (e) rs1554286

Association between rs1800871 polymorphism and risk of BD

In total, we identified nineteen studies [7, 28–40] which contained 6854 cases and 9911 controls assessed the effect of the IL-10 -819C/T polymorphism in the occurrence of BD. By using the random-effects model, meta-analysis revealed a significant association between BD and the IL-10 -819C/T polymorphism under the allelic (OR = 0.691, 95% CI: 0.626–0.762, P < 0.001), homozygous (OR = 0.466, 95% CI: 0.368–0.589, P < 0.001), dominant (OR = 0.692, 95% CI: 0.584–0.820, P < 0.001), and recessive (OR = 0.557, 95% CI: 0.405–0.767, P < 0.001) models, while no significant association was found under the heterozygous model (P = 0.384) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Association between rs1800872 polymorphism and risk of BD

For IL-10 -592C/A polymorphism, thirteen studies [7, 28, 29, 31–33, 35, 39, 41, 42] were involved composed of 3132 BD patients and 3638 controls. The results of the combined analysis of the association between -592 polymorphism and BD are summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 2. There were significant associations for C vs. A allele, CC + CA vs. AA and CA vs. AA genotypes; however, other comparisons failed to obtain any significant association.

Association between rs1518111 polymorphism and risk of BD

Thirteen studies [8, 26, 35, 37, 38, 40], including 5519 cases and 5643 controls focused on the relationship between rs1518111 polymorphism and BD risk. The combined results (Table 2 and Fig. 2) showed significant differences in all models between BD cases and healthy controls.

Association between rs1554286 polymorphism and risk of BD

In total, three studies [26, 28, 36] which contained 2421 cases and 3429 controls were performed to assess the importance of rs1554286 polymorphism for BD susceptibility. As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2, this polymorphism was found to be significantly associated with BD susceptibility under all models.

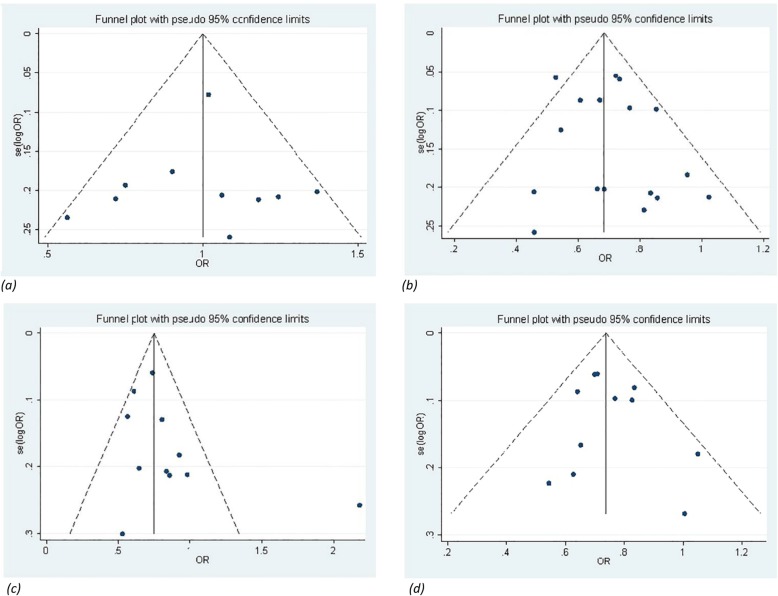

Heterogeneity and publication bias

A funnel plot was used to reveal any publication bias influencing the analysis. The funnel plots did not show a significant sign of asymmetry for IL-10 polymorphisms. For rs1554286, a funnel plot was not performed because it is useless when the number of studies is limited (Fig. 3). The Metareg’s test and Egger’s test were also conducted and the findings showed a lack of publication bias among all comparison models except heterozygous (CC vs. CT + TT) model of rs1800871.

Fig. 3.

Begg’s funnel plot for publication bias analysis of the IL-10 polymorphisms with BD. Symmetry in Begg’s funnel plots demonstrate the absence of publication bias in the studies investigating the association of (a) rs1800896 (b) rs1800871 (c) rs1800872 (d) rs1518111

To test heterogeneity among the selected studies, the I2 statistic was employed. The heterogeneity was significant under the genetic models of CC vs. CT + TT and CT vs. TT of rs1800871. After excluding the study by Kirino [40], the heterogeneity was eliminated (I2 = 44.3, association P < 0.001) and (I2 = 19.6, association P < 0.001), respectively. Significant heterogeneity was detected in C vs. T model of rs1554286 polymorphism. It can be due to a small number of studies included in this analysis. Therefore, the random-effects model was applied to synthesize the data (Table 2).

Discussion

In order to better understand the possible genetic association of the IL-10 gene polymorphisms and BD, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis using pooling the results of the independent usable studies to determine whether the IL-10 polymorphisms have a potential impact on the BD susceptibility.

Behçet’s disease is a multi-system inflammatory disorder with complex etiology, therefore genes involved in the immune system and inflammatory responses are potential candidate genes for the BD development. In addition to HLA-B51 as the strongest genetic factor for BD, which explains 20% incidence of BD [43, 44], GWAS and subsequent genetic studies have identified a number of non-HLA potent loci for the susceptibility and organ damages of this disease, such as cytokines (IL-4 [45], IL-6 [46], IL-10 [7, 40], CCL2 [47, 48], TNF-α [49]), ERAP1 [40], UBASH3B [50, 51], STAT4 [52].

Several studies have been conducted on the influence and impression of the interleukin-10 gene and its protein on the probability of the multiple autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, such as BD relying on its chromosomal location and functional relevance.

Research on the effect of IL-10 on various inflammatory models has led to different and sometimes contradictory results even in the same models, indicating that there are intricate influenced agents on the regulation of cellular responses by IL-10. In the experimental study by Rizzo et al. [53] indicated that IL-10 knockout mice had a susceptibility to develop the Experimental Autoimmune Uveoretinitis (EAU) in comparison to controls, also, IL-10-treatment in induced mice for the EAU showed a resistance to the disease. Other animal studies have also confirmed the protective effect of IL-10 on the ocular inflammation and CNS autoimmune [54–56]. Some studies on BD have observed a reduction in IL-10 protein level in BD patients’ peripheral blood and aqueous humor [13, 30, 41, 57], while in other studies, there has been an increase in the concentration of this protein in plasma and active ulcers of BD [58–63]. On the other hand, there is a study that has not recorded significant changes between patients and controls [64]. Similar to the protein concentration determination studies, the results of the mRNA expression level were varied among previous studies. Several investigations [13, 41, 64] have shown low expression of the IL-10 mRNA in B cells and serums of BD patients. In contrast, Ahmed Ben et al. [65] have reported a high expression of the IL-10 mRNA in oral/genital ulcers, pseudofolliculitis lesions and sites of positive pathergy test. In contrast, Balkan et al. [66] found no significant difference in the IL-10 mRNA expression.

So far, different factors have been studied in the production and regulatory the role of IL-10. One of these influential factors that have recently been studied on IL-10 is epigenetic agents. The study of Alipour et al. [13] showed a hyper-methylation on IL-10 gene promoter region. Genetic variants are other factors that account for up to 75% of the IL-10 expression variance in inter-individual human [67]. Investigation of the polymorphic region in the transcriptional regulation of IL-10 gene may be helpful in predicting inflammatory diseases such as BD. Three common polymorphisms of IL-10 (− 1082G/A, − 819C/T and -592C/A) have been evaluated in detail for their impacts on gene transcription. In vitro studies showed that the highest IL-10 expression has been observed in GCC (− 1082/− 819/− 592) haplotype and lowest expression in AT (− 1082/− 819) haplotype [68–70]. However, studies on BD have not confirmed the effects of the above alleles [30]. In addition to the promoter variants, the intronic variant of rs1518111 is also likely to influence transcription [66].

The present meta-analysis was performed to examine the association between the IL-10 polymorphisms (− 1082, − 819, − 592, rs1518111, and rs1554286) and BD susceptibility in different ethnic groups including East Asian, Middle Eastern, European, and African populations. The strongest associations were observed in the comparisons of allele and genotypes of − 819C/T promoter SNP, rs1518111G/A intronic SNP, and rs1554286C/T intronic SNP. The overall results indicated the protective impact of these polymorphisms against the disease. So that, individuals carrying C allele of −819 and rs1554286 have 31 and 42% lower risk of developing BD, respectively. We also achieved significant association in -592C/A promoter SNP, which showed a relatively protective role against BD. However, the comparisons of allele and genotypes of -1082G/A promoter SNP failed to demonstrate any significant association.

However, our results should be interpreted cautiously, with respect to the following limitation reasons. First, limited number of included studies in some studied SNPs; second, heterogeneity and publication bias, for instance, missing articles due to unpublished studies, possibly with negative results, and/or language bias due to writing in other languages (except English and Persian); third, lack of sufficient data on the characteristics and symptoms of the participants in most of the primary studies to perform subgroups analysis, such as based on age, gender and the disease activity; lastly, some genotype distributions of control groups do not follow the HWE.

Conclusions

Our data demonstrated significant associations of the IL-10 polymorphisms with BD. Accordingly, the polymorphisms of -819, − 592, rs1518111 and rs1554286 play relatively protective roles against Behcet’s disease.

Methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive search for the IL-10 polymorphisms and BD was performed in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus databases for articles in English, and SID, Magiran, IranMedex, and IranDoc for articles in Persian up to February 2019 according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist and PICO approach [43]. The most relevant articles were identified by computerized searches using relevant text words and medical subject headings (MeSH) that included all spellings and combination of “Behcet’s syndrome” or “Behcet’s disease” and “Interleukin-10” or “IL-10”. Besides, we hand-searched reference lists of selected publications and previous meta-analysis study to ensure that all relevant studies and recent reviews were included. The search was limited to case-control studies and Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS). No restrictions were placed on race, ethnicity or geographic area publication date.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A study was included in this meta-analysis if (1) it was published by February 2019, (2) it was a case-control study or GWAS that determined the distributions of the IL-10 -1082G/A, −819C/T, −592C/A, rs1518111G/A, and rs1554286C/T polymorphisms, in patients with BD and controls, (3) it contained original data, and (4) it provided enough data to calculate odds ratios (ORs). Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Keywords/search terms/reviews, and abstract scanning criteria, (2) the study was a review or abstract and publications in duplicate, (3) unrelated to each of BD and these polymorphisms, (4) studies involving family members, because their analysis was based on linkage considerations, and (5) papers do not involve human subjects.

Data extraction

Two authors (E.S. and N.R.) independently extracted the following data from all studies selected by using a study-specific data extraction form: first author’s name, year of publication, ethnicity, mean age of participants, number of cases and controls and method for determination of genotype, studied polymorphisms, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P-values. Any disagreement between authors was resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached. If they failed to reach an agreement, a third author (M.G.) was consulted to resolve the discrepancies. Due to the lack of the mean age and HWE P-values for some studies, we were not able to analyze the data based on this information. This study was conducted in the Liver and Gastrointestinal Disease Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Statistical analyses

All statistical manipulations were performed with STATA version-15.0 software (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas). The strength of the association between IL-10 polymorphisms and BD was assessed by calculating pooled OR and 95% CI values in the following genetic models: allelic model (G vs. A, C vs. A, C vs. T), dominant model (GG + GA vs. AA, CC + CT vs. TT, CC + CA vs. AA), recessive model (GG vs. GA + AA, CC vs. CT + TT, CC vs. CA + AA), homozygous model (GG vs. AA, CC vs. TT, CC vs. AA) and heterozygous model (AG vs. AA, CT vs. TT, CA vs. AA). Z-test with P < 0.05 was used to authenticate the statistical significance of effect size. Sensitivity analysis was used to investigate the cause of dispersion. Then, outlier studies were removed and analysis was recomputed. In the case of a significant reduction in dispersion (I2 index), this study was considered as a dispersion factor. With regard to the heterogeneity of the studies, Cochran’s Q test (p-value [phet] < 0.10 was considered as statistically significant heterogeneity) and I2 statistics (75 ≤ I2 < 100 as extreme heterogeneity, 50 ≤ I2 < 75 as high heterogeneity, 25 ≤ I2 < 50 as moderate heterogeneity, and I2 < 25 as no heterogeneity) were used to assess the degree of heterogeneity [71]. The random-effects model was used for meta-analysis because it accounts for random variability both within and among studies. Publication bias was investigated by Funnel plot and Egger’s test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Acknowledgements

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Student Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran (63975).We would like to thank “Student Research Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences”. Furthermore, we would like to express our deepest appreciation to Dr. Elaine F. Remmers, Dr.Nobuhisa Mizuki, Dr.Maria Francisca Gonzalez-Escribano and Dr.Joana M Xavier those who provided us with the possibility to complete our data.

Abbreviations

- BD

Behcet’s disease

- CI

Confidence Interval

- EAU

Experimental Autoimmune Uveoretinitis

- GWAS

Genome-Wide Association Study

- HWE

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- IL-10

Interleukin-10

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- OR

Odds Ratio

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

Authors’ contributions

Elham Shahriyari participated in conception and design, searching and selecting papers, data extraction, analyzing data, writing and approving final paper. L.V. participated in the selection of title, keywords, and approving final paper. N.R. participated in searching and selecting papers and approving final paper. M.A. participated in methodological and statistical advice, and approving final paper. A.K participated in data extraction and approving final paper. M.G. participated in conception and design, searching and selecting papers, data extraction, analyzing data, writing and approving final paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding and first authors on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval is not required, as our study does not include confidential participant data and interventions. We disseminated our results through previous publications.

Consent for publication

The meta-analysis is exempt from informed consent because we collected and analyzed data from previous publications in which informed consent had already been obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Leila Vahedi, Email: Vahedi.l49@gmail.com.

Maryam Ghaffari Laleh, Email: maryam.ghaffari69@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Davatchi F, Shahram F, Chams-Davatchi C, Shams H, Nadji A, Akhlaghi M, et al. Behcet’s disease: from east to West. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(8):823–833. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendes D, Correia M, Barbedo M, Vaio T, Mota M, Gonçalves O, et al. Behçet’s disease–a contemporary review. J Autoimmun. 2009;32(3–4):178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamoun M, Karray E, Zakraoui I. Association of small ubiquitin-like modifier 4 (SUMO4) polymorphisms in a Tunisian population with Behcet's disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol.2010;28 suppl (4):S45. [PubMed]

- 4.Verity DH, Marr JE, Ohno S, Wallace GR, Stanford MR. Behçet’s disease, the silk road and HLA-B51: historical and geographical perspectives. Tissue Antigens. 1999;54(3):213–220. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.1999.540301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonardo Nieves Marie, McNeil Julian. Behcet’s Disease: Is There Geographical Variation? A Review Far from the Silk Road. International Journal of Rheumatology. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/945262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendoza-Pinto C, García-Carrasco M, Jiménez-Hernández M, Hernández CJ, Riebeling-Navarro C, Zavala AN, et al. Etiopathogenesis of Behcet's disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9(4):241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizuki N, Meguro A, Ota M, Ohno S, Shiota T, Kawagoe T, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify IL23R-IL12RB2 and IL10 as Behçet's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42(8):703–706. doi: 10.1038/ng.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Remmers EF, Cosan F, Kirino Y, Ombrello MJ, Abaci N, Satorius C, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions associated with Behcet’s disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:698–702. doi: 10.1038/ng.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace G. Novel genetic analysis in Behcet’s disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:123. doi: 10.1186/ar2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meguro A, Inoko H, Ota M, Katsuyama Y, Oka A, Okada E, et al. Genetics of Behcet disease inside and outside the MHC. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:747–754. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alipour S, Nouri M, Sakhinia E, Samadi N, Roshanravan N, Ghavami A, et al. Epigenetic alterations in chronic disease focusing on Behcet’s disease: review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;91:526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.04.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gul A. Behcet’ disease: an update on the pathogenesis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19(5 Suppl 24):S6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alipour S, Nouri M, Khabbazi A, Samadi N, Babaloo Z, Abolhasani S, et al. Hypermethylation of IL-10 gene is responsible for its low mRNA expression in Behçet’s disease. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(8):6614–6622. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Commins S, Steinke JW, Borish L. The extended IL-10 superfamily: iL-10, IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24, IL-26, IL-28, and IL-29. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(5):1108–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iyer SS, Cheng G. Role of interleukin 10 transcriptional regulation in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Crit Rev Immunol. 2012;32:23–63. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rennick DM, Fort MM, Davidson NJ. Studies with IL-10−/− mice: an overview. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61(4):389–396. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer SD, Di Marco F, Hooley J, Pitts-Meek S, Bauer M, Ryan AM, et al. The orphan receptor CRF2–4 is an essential subunit of the interleukin 10 receptor. J Exp Med. 1998;187(4):571–578. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbara G, Xing Z, Hogaboam CM, Gauldie J, Collins SM. Interleukin 10 gene transfer prevents experimental colitis in rats. Gut. 2000;46(3):344–349. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Deventer SJ, Elson CO, Fedorak RN. Multiple doses of intravenous interleukin 10 in steroid-refractory Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s Disease Study Group Gastroenterology. 1997;113(2):383–389. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding L, Linsley PS, Huang LY, Germain RN, Shevach EM. IL-10 inhibits macrophage costimulatory activity by selectively inhibiting the up-regulation of B7 expression. J Immunol. 1993;151(3):1224–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pineton de Chambrun MP, Wechsler B, Geri G, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. New insights into the pathogenesis of Behcet’s disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11(10):687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morton LT, Situnayake D, Wallace GR. Genetics of Behçet’s disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28(1):39–44. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eskdale J, Wordsworth P, Bowman S, Field M, Gallagher G. Association between polymorphisms at the human IL-10 locus and systemic lupus erythematosus. Tissue Antigens. 1997;49(6):635–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1997.tb02812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guzowski D, Chandrasekaran A, Gawel C, Palma J, Koenig J, Wang XP, et al. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter region of interleukin-10 by denaturing highperformance liquid chromatography. J Biomol Tech. 2005;16(2):154–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.1000 Genomes Project Consortium A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xavier JM, Shahram F, Davatchi F, Rosa A, Crespo J, Abdollahi BS, et al. Association study of IL10 and IL23R–IL12RB2 in Iranian patients with Behcet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(8):2761–2772. doi: 10.1002/art.34437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barış S, Akyürek Ö, Dursun A, Akyol M. The impact of the IL-1β, IL-1Ra, IL-2, IL-6 and IL-10 gene polymorphisms on the development of Behcet’s disease and their association with the phenotype. Med Clin (Barc) 2016;146(9):379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu J, Hou S, Zhu X, Fang J, Zhou Y, Liu Y, et al. Interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms are associated with Behcet’s disease but not with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome in the Chinese Han population. Mol Vis. 2015;21:589–603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Okaily F, Arfin M, Al-Rashidi S, Al-Balawi M, Al-Asmari A. Inflammation-related cytokine gene polymorphisms in Behçet’s disease. J Inflamm Res. 2015;8:173–180. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S89283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talaat RM, Ashour ME, Bassyouni IH, Raouf AA. Polymorphisms of interleukin 6 and interleukin 10 in Egyptian peoplewith Behcet’s disease. Immunobiology. 2014;219(8):573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shahram F, Nikoopour E, Rezaei N, Saeedfar K, Ziaei N, Davatchi F, Amirzargar A. Association of interleukin-2, interleukin-4 and transforming growth factor-beta gene polymorphisms with Behçet’s disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(4 Suppl 67):S28–S31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ateş O, Dalyan L, Hatemi G, Hamuryudan V, Topal-Sarıkaya A. Analyses of functional IL10 and TNF-a genotypes in Behcet’s syndrome. Mol Biol Rep. 2010;37(7):3637–3641. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dilek K, Ozcimen AA, Saricaoglu H, Saba D, Yucel A, Yurtkuran M, et al. Cytokine gene polymorphisms in Behçet's disease and their association with clinical and laboratory findings. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(2 suppl 53):S73–S78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace GR, Kondeatis E, Vaughan RW, Verity DH, Chen Y, Fortune F, et al. IL-10 genotype analysis in patients with Behçet’s disease. Hum Immunol. 2007;68(2):122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kramer M, Hasanreisoglu M, Weiss S, Kumova D, Schaap-Fogler M, Guntekin-Ergun S, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in IL23R-IL12RB2 (rs1495965) are highly prevalent in patients with Behcet’s uveitis, and vary between populations. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27(5):766–773. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2018.1467463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu H, Zheng M, Zhang L, Li H, Zhu Y, Cheng L, et al. Identification of susceptibility SNPs in IL10 and IL23R-IL12RB2 for Behçet’s disease in Han Chinese. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(2):621–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carapito R, Shahram F, Michel S, Le Gentil M, Radosavljevic M, Meguro A, et al. On the genetics of the silk route: association analysis of HLA, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions with Behçet’s disease in an Iranian population. Immunogenetics. 2015;67(5–6):289–293. doi: 10.1007/s00251-015-0841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Z, Zheng W, Xu J, Sun F, Chen H, Li P, et al. IL10 polymorphisms associated with Behçet’s disease in Chinese Han. Hum Immunol. 2014;75(3):271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khaib Dit Naib O, Aribi M, Idder A, Chiali A, Sairi H, Touitou I, et al. Association analysis of IL10, TNF-α, and IL23R-IL12RB2 SNPs with Behçet’s disease risk in Western Algeria. Front Immunol. 2013;4:342. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirino Y, Bertsias G, Ishigatsubo Y, Mizuki N, Tugal-Tutkun I, Seyahi E, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for Behcet’s disease and epistasis between HLA-B* 51 and ERAP1. Nat Genet. 2013;45(2):202–207. doi: 10.1038/ng.2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Afkari B, Babaloo Z, Dolati S, Khabazi A, Jadidi-Niaragh F, Talei M, et al. Molecular analysis of interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms in patients with Behçet’s disease. Immunol Lett. 2018;194:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montes-Cano MA, Conde-Jaldón M, García-Lozano JR, Ortiz-Fernández L, Ortego-Centeno N, Castillo-Palma MJ, et al. HLA and non-HLA genes in Behçet’s disease: a multicentric study in the Spanish population. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):R145. doi: 10.1186/ar4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khabbazi A, Vahedi L, Ghojazadeh M, Pashazadeh F, Khameneh A. Association of HLA-B27 and Behcet’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Auto Immun Highlights. 2019;10(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13317-019-0112-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yazici Y, Yurdakul S, Yazici H. Behcet’s syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(6):429–435. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0132-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inanir A, Tural S, Yigit S, Kalkan G, Pancar GS, Demir HD, et al. Association of IL-4 gene VNTR variant with deep venous thrombosis in Behçet’s disease and its effect on ocular involvement. Mol Vis. 2013;19:675–683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu Y, Zhou K, Yang Z, Li F, Wang Z, Xu F, et al. Association of cytokine gene polymorphisms (IL 6, IL 12B, IL 18) with Behcet’s disease : a meta-analysis. Z Rheumatol. 2016;75(9):932–938. doi: 10.1007/s00393-015-0036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghaffari Laleh M, Jabbarpour Bonyadi M, Jabbarpour Bonyadi MH. STUDYING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN POLYMORPHISMS -2518A/G MCP-1 GENE WITH BEHCET’S DISEASE IN THE POPULATION OF THE NORTH WEST OF IRAN. article in Persian. J Urmia Univ Med Sci. 2017;28(6):418–424. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hou S, Yang P, Du L, Jiang Z, Mao L, Shu Q, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein–1− 2518 a/G single nucleotide polymorphism in Chinese Han patients with ocular Behçet’s disease. Hum Immunol. 2010;71(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.09.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdolmohammadi R, Bonyadi M. Polymorphisms of promoter region of TNF-α gene in Iranian Azeri Turkish patients with Behçet’s disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32(1):33–37. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fei Y, Webb R, Cobb BL, Direskeneli H, Saruhan-Direskeneli G, Sawalha AH. Identification of novel genetic susceptibility loci for Behçet’s disease using a genome-wideassociation study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(3):R66. doi: 10.1186/ar2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shahriyari E, Bonyadi M, Jabbarpoor Bonyadi MH, Soheilian M, Yaseri M, Ebrahimiadib N. Ubiquitin associated and SH3 domain containing B (UBASH3B) Gene Association with Behcet’s disease in Iranian population. Curr Eye Res. 2019;44(2):200–205. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2018.1524913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hou S, Yang Z, Du L, Jiang Z, Shu Q, Chen Y, et al. Identification of a susceptibility locus in STAT4 for Behçet’s disease in Han Chinese in a genome-wide association study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(12):4104–4113. doi: 10.1002/art.37708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rizzo LV, Xu H, Chan CC, Wiggert B, Caspi RR. IL-10 has a protective role in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis. Int Immunol. 1998;10(6):807–814. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Kozak Y, Verwaerde C. Cytokines in immunotherapy of experimental uveitis. Int Rev Immunol. 2002;21(2–3):231–253. doi: 10.1080/08830180212060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fang IM, Lin CP, Yang CH, Chiang BL, Yang CM. Chau LY, et al inhibition of experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis by adenovirus-mediated transfer of the Interleukin-10 gene. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(6):420–428. doi: 10.1089/jop.2005.21.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X, Koldzic DN, Izikson L, Reddy J, Nazareno RF, Sakaguchi S, et al. IL-10 is involved in the suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by CD25+CD4+regulatory T cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16(2):249–256. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahn JK, Yu HG, Chung H, Park YG. Intraocular cytokine environment in active Behçet uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(3):429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turan B, Gallati H, Erdi H, Gürler A, Michel BA, Villiger PM. Systemic levels of the T cell regulatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-12 in Bechçet's disease; soluble TNFR-75 as a biological marker of disease activity. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(1):128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raziuddin S, Al-Dalaan S, Bahabri S, Siraj AK, Al-Sedairy S. divergent cytokine production profile in Behçet's disease. Altered Th1/Th2 cell cytokine pattern. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(2):329–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hamzaoui K, Hamzaoui A, Guemira F, Bessioud M, Hamza M, Ayed K. Cytokine profile in Behçet’s disease patients. Relationship with disease activity. Scand J Rheumatol. 2002;31(4):205–210. doi: 10.1080/030097402320318387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aridogan BC, Yildirim M, Baysal V, Inaloz HS, Baz K, Kaya S. Serum levels of IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13 and IFN-gamma in Behçet’s disease. J Dermatol. 2003;30(8):602–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guenane H, Hartani D, Chachoua L, Lahlou-Boukoffa OS, Mazari F, Touil-Boukoffa C. Production of Th1/Th2 cytokines and nitric oxide in Behçet’s uveitis and idiopathic uveitis. article in French. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2006;29(2):146–152. doi: 10.1016/S0181-5512(06)73762-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.El-Asrar AM, Struyf S, Kangave D, Al-Obeidan SS, Opdenakker G, Geboes K, et al. Cytokine profiles in aqueous humor of patients with different clinical entities of endogenousuveitis. Clin Immunol. 2011;139(2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoon JY, Lee Y, Yu SL, Yoon HK, Park HY, Joung CI, et al. Aberrant expression of interleukin-10 and activation-induced cytidine deaminase in B cells from patients with Behçet’s disease. D Biomed Rep. 2017;7(6):520–526. doi: 10.3892/br.2017.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ben Ahmed M, Houman H, Miled M, Dellagi K, Louzir H. Involvement of chemokines and Th1 cytokines in the pathogenesis of mucocutaneous lesions of Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(7):2291–2295. doi: 10.1002/art.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balkan E, Bilen H, Eyerci N, Keleş S, Kara A, Akdeniz N, et al. Cytokine, C-reactive protein, and heat shock protein mRNA expression levels in patients with active Behçet’s uveitis. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:1511–1516. doi: 10.12659/MSM.907918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Westendorp RG, Langermans JA, Huizinga TW, Elouali AH, Verweij CL, Boomsma DI, et al. Genetic influence on cytokine production and fatal meningococcal disease. Lancet. 1997;349(9046):170–173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)06413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rad R, Dossumbekova A, Neu B, Lang R, Bauer S, Saur D, et al. Cytokine gene polymorphisms influence mucosal cytokine expression, gastric inflammation, and host specific colonization during helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 2004;53(8):1082–1089. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.029736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Turner DM, Williams DM, Sankaran D, Lazarus M, Sinnott PJ, Hutchinson IV. An investigation of polymorphism in the interleukin-10 gene promoter. Eur J Immunogenet. 1997;24(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2370.1997.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eskdale J, Wordsworth P, Bowman S, Field M, Gallagher G. Association bet ween polymorphisms at the human IL- I0 locus and systemic lupus erythematosus. Tissue Antigens. 1997;49(6):635–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1997.tb02812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, AltmanDG Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding and first authors on reasonable request.