Abstract

The increasing incidence of caesarean delivery (CD) has resulted in a rise in placenta accreta spectrum (PAS), adversely impacting maternal outcomes globally. Currently, more than 90% of women diagnosed with PAS present with a placenta previa (previa PAS). Previa PAS can be reliably diagnosed antenatally with ultrasound, it is unclear if magnetic resonance imaging improves diagnosis beyond what can be achieved by skilled ultrasound operators. Therefore, any screening programme for PAS will require improved training in diagnosis of placental disorders and development of targeted scanning protocols. Management strategies for previa PAS vary depending on the accuracy of prenatal diagnosis, findings at laparotomy and local surgical expertise. Current epidemiological data for PAS are highly heterogeneous, mainly due to wide variation in the clinical criteria used to diagnose the condition at birth. This significantly impacts research into all aspects of the condition but especially comparison of the efficacy of different management strategies.

Keywords: Placenta accreta, increta, percreta, ultrasound imaging, caesarean hysterectomy, prenatal diagnosis

Summary

The recent rapid increase in caesarean delivery (CD) rates has changed the epidemiology of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) worldwide from a rare, serious, pathological condition to an increasingly common major obstetric complication. The risk of placenta previa increases following CD, and women presenting with a lowlying/placenta previa and history of CD are at the highest risk of PAS (previa PAS). Prenatal identification has been shown to improve the outcomes in PAS. In specialist centres, the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound in identifying previa PAS is over 90% so there is often no need for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Exceptions include where the placenta cannot be fully interrogated with ultrasound, for example a posterior previa with extensive fetal shadowing. Ultrasound screening for PAS requires development of targeted training with standardised protocols and reporting tools. A planned preterm caesarean hysterectomy with the placenta left in situ is the strategy often used for PAS although conservative management may be considered when the woman wants fertility preservation. Access to specialist centres with multidisciplinary expertise and essential resources such as blood products and neonatal and maternal intensive care is pivotal to improving the management of these complex cases. There are no RCTs or prospective, well-controlled observational studies comparing surgical and conservative management strategies. The evaluation of epidemiological trends and management outcomes has been limited to date by poor quality study design, in particular by the lack of a standardized description of the clinical grade of PAS at birth and histopathologic confirmation of the clinical diagnosis.

RESEARCH AGENDA

There is a need for prospective studies on the diagnosis and management of PAS using standardised protocols for reporting on the prenatal imaging diagnostic criteria and on the clinical grade of PAS of birth including histopathologic confirmation of the clinical diagnosis when possible. No further progress will be made in evaluating the epidemiology and outcome of PAS until all studies present data that differentiate accurately between cases that exclusively adherent and cases that are invasive.

PLACENTA ACCRETA SPECTRUM

A. Historical perspective

Irving and Hertig were the first to publish a case series of placenta accreta in 1937 and included a literature review of the cases published before then. They reported that the first case of “placenta accreta” may have been Mrs. Galla who died at delivery in 1588 and was found at autopsy to have a placenta previa “firmly adherent” to the internal os. Langhans (2) and Hart (3), described the histology of placenta accreta at the end of the 19th century, and used the term “adherent placenta,” whereas Baisch (4) was the first author to use to term “placenta accreta” in 1907.

In 1966, Lukes et al (5) proposed a histological classification for placenta accreta based on the depth of the villous penetration of the myometrium. They separated placenta accreta into three categories: placenta adherenta or creta (PC) when the villi adhere directly to the myometrium without a decidual interface, placenta increta (PI) when the villi invade the myometrium and placenta percreta (PP) when the villi invade the full thickness of the uterine wall including the serosa (Figure 1). Percreta villi can also invade organs, tissues and the pelvic vasculature beyond the uterine serosa. This terminology is still used today by most pathologists. Luke et al., also highlighted the fact that villous penetration of the myometrium is rarely uniform and that both adherent and invasive villi may co-exist in the same specimen (Figure 2). The term placenta accreta spectrum (PAS), which includes all grades of abnormal placentation, is now the preferred umbrella term to define this heterogeneous condition, and has been recently endorsed by the FIGO (6), the RCOG (7) the ACOG and the SMFM (8).

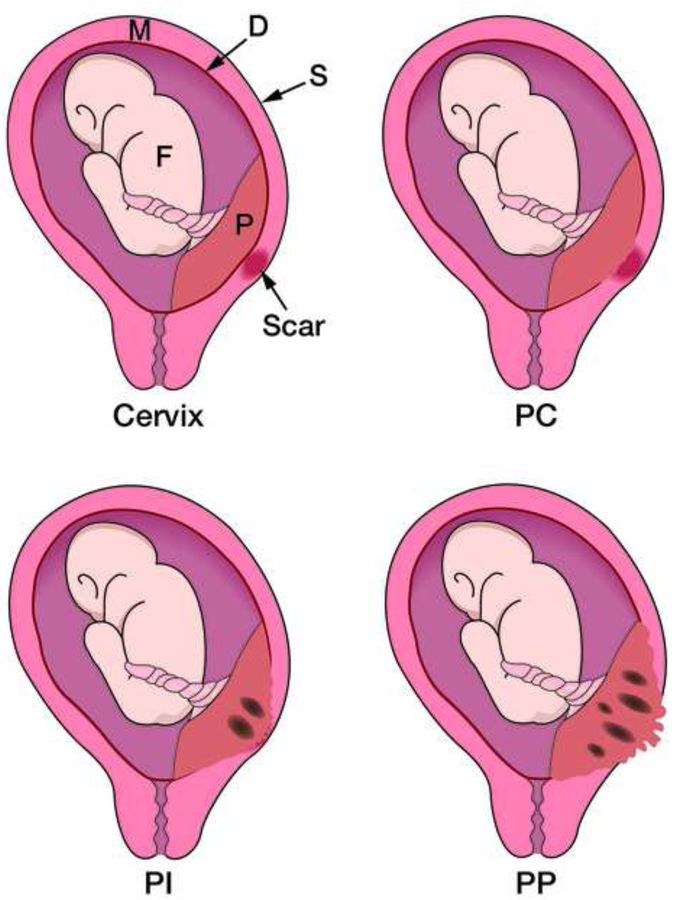

Fig 1:

Diagram showing an anterior placenta previa on a caesarean scar and the different grades of placenta previa accreta: Creta (PC) where placental (P) villi adhere to the myometrium (M), Increta (PI) where the villi invade the myometrium and Percreta (PP) where the villi invade the entire myometrium and cross the uterine serosa (S). From reference 50.

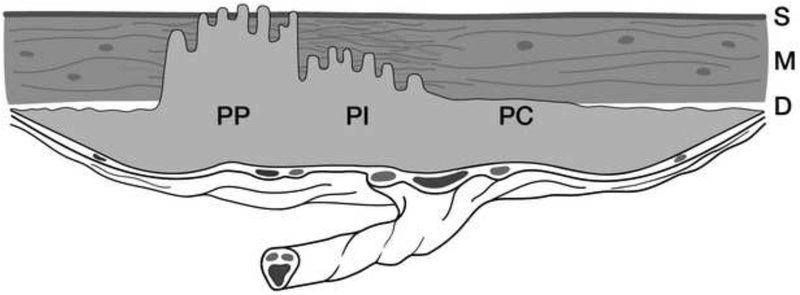

Fig 2:

Diagram showing an anterior placenta previa accreta combining areas of abnormal adherence and invasion: Creta (PC), Increta (PI) and Percreta (PP). D= Decidua; M= myometrium; S= Serosa. From reference 50.

B. Modern perspective

The first descriptions of PAS in the international medical literature (9,10) coincided with the first published reports on outcomes of contemporary caesarean delivery (CD) techniques, one century ago (11,12). A CD was rarely performed in the first half of the 20th century. Unsurprisingly, only one of the 20 cases personally treated by Irving and Hertig in 1937 occurred after CD (1). CD has now become an essential component of modern maternity care and epidemiological studies have shown a strong association between CD rates, number of prior CDs and the incidence of PAS (13). The steady increase PAS can be directly linked with the increase in CD rates in both low and high-resources countries, with rates rising from less than 7% in 1990s to well over the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation of 15% in just 2 decades (14). In middle-income countries such as Turkey, Mexico, Brazil and Egypt, more than half of all births are via caesarean, mostly elective. Consequently, in countries with high-birth rates, like Egypt, the prevalence and negative impact of PAS will rapidly outweigh the benefits of improved access to quality obstetric care.

Increased CDs have also increased the incidence of placenta previa (15). The relative risk for placenta previa increases with each prior CD from 4.5% (95% CI 3.6 to 5.5) for one to 7.4 (95% CI 7.1 to 7.7) for two, 6.5 (95% CI 3.6 to 11.6) for three, and 44.9 (95% CI 13.5 to 149.5) for four or more when compared to vaginal delivery (16). Overall, the incidence of placenta previa increases from 10/1000 deliveries after one previous CD to 28/1000 after three or more CDs (17). Similarly, in women with prior CD presenting with a placenta previa, the risk of PAS is 3%, 11%, 40%, 61%, and 67% for first, second, third, fourth, and fifth or more CD, respectively (18). The UK national case-control study reported that the incidence of PAS increases from 1.7 per 10,000 to 577 per 10,000 births in women presenting with a placenta previa and a prior CD (19).

Currently, more than 90% of women diagnosed with PAS also have a placenta previa (20), the combination of both conditions leads to high maternal morbidity and mortality due to massive haemorrhage at the time of birth (21,22). Maternal mortality of placenta previa with percreta has been reported to be as high as 7% of cases (23). The 2017 report from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths indicated that although there was no significant change in maternal death rates in the UK, between 2010–12 and 2013–15, there has been an increase in the number of deaths of women presenting with PAS (24).

PAS is not exclusively a consequence of CD and has been reported in primiparous women with a history of operative hysteroscopy, suction curettage, surgical termination and endometrial ablation (25,26). In fact, any uterine pathology such as bicornuate uterus, adenomyosis, submucous fibroids and myotonic dystrophy or any procedure causing surgical damage to the uterine wall integrity has been associated with PAS (13,25). Accreta placentation can occur after myomectomy but the risk is relatively low (27). Finally, in vitro fertilization (IVF), especially with cryopreserved embryos increases the risk for PAS from between 4- to 13-fold. PAS is primarily a consequence of modern obstetric and reproductive practices, and is likely to become increasingly common as women delay childbearing, require reproductive assistance and enter pregnancy with medical co-morbidities (25).

DIAGNOSING PAS AT BIRTH

The clinical diagnostic criteria of PAS used since the publication by Irving and Hertig (1) in 1937 have been heterogeneous and vague (29,30). Not surprisingly, the reported prevalence of PAS at delivery has been highly variable ranging between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 40,000 and deliveries (13) and our recent systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of PAS indicates rates ranging between 0.01% and 1% (30). An expert review of literature published between 1977 and 2012 found that the pooled prevalence was 1 in 588 deliveries, however this reflected data from referral centres, which treat more cases than in the general population (28). Histopathologic examination remains the confirmatory gold standard, but most current authors of PAS cohort series do not provide complete and transparent information on both clinical and histopathological findings. The clinical and pathologic diagnostic standards have stagnated, with little change since 1937.

A. Clinical diagnosis

The clinical signs of PAS disorders, in particular in cases of a partially adherent placenta, can be very similar to those of placental retention, i.e. difficult manual or piecemeal removal of the placenta; absence of spontaneous placental separation 20–30 min after birth, despite active management including bimanual massage of the uterus, use of oxytocin and controlled traction of the umbilical cord; retained placental fragments requiring curettage after vaginal birth and; heavy bleeding from the placental bed after placental removal during CD (33–38). Some authors include sonographic evidence of retained placenta tissue requiring curettage (33). These various criteria are used by many authors and explain the wide heterogeneity in the evaluation of the prevalence of PAS in the general obstetric population (30). A retained placenta, which is merely entrapped inside the uterine cavity owing to constriction of the cervix, should not be included in the category of PAS nor should cases where a retained placenta is removed whole or spontaneously delivered within 24h after birth.

Macroscopic changes detected upon entry to the abdomen can also raise suspicion to the presence of accreta placentation such as tortuous large varicosities seen on the serosal surface, distended bulging lower uterine segment, or direct extension of placenta onto the uterine surface, bladder, or pelvic sidewalls (38). Most of these gross changes are common in multiparous and thus at the other end of the spectrum it is pivotal to make the differential diagnosis between a scar dehiscence and a placenta percreta. Women with a history of multiple lower-segment CDs may have an anterior myometrial wall largely consisting of fibrotic scar tissue (31,32). Myofibre loss and the excessive accumulation of collagen impairs the function of muscular tissue, which loses elasticity and becomes more prone to dehiscence and rupture in subsequent pregnancies. Lower-segment dehiscence becomes more pronounced as pregnancy advances due to the pressure of the fetus and uterine contractions, both of which increase the disruption of the fibrotic tissue. This can create a large uterine “window” made only of serosa, and through which a portion of the placenta is visible without any villous tissue truly invading the serosa and/or the surrounding myometrium (Figure 3). The high prevalence of PAS in some population studies (33–37) and rates of successful conservative surgical management (39–42) in recent cohort studies may reflect inclusion of a large proportion of cases of non-accreta placental retention and/or uterine dehiscence in their data.

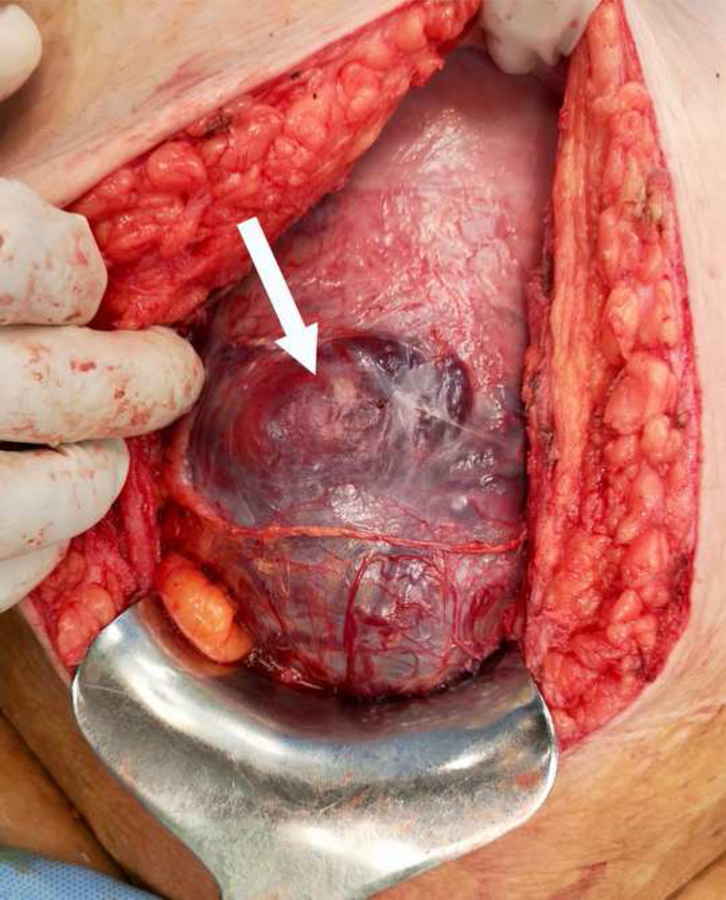

Fig 3:

Large myometrial dehiscence at 35 weeks (arrow) due to multiple prior CDs creating a “uterine window” where part of the underlying placenta tissue is visible through the serosa mimicking a placenta percreta.

Several authors have also report using the World Health Organization (WHO) international statistical classification of diseases (ICD-10) and related health problems to describe the clinical diagnosis of PAS (43–45). WHO ICDs are designed for health information managers, coders, policy-makers, insurers and patient organizations to classify diseases (www.who.int/classifications/icd). This classification provides no clinical description of the condition, makes no distinction between adherent and invasive accreta placentation, and relies upon accurate coding. In 2016, Collins et al proposed a grading system to clearly assess the severity of PAS using clinical findings at birth (46). This system has been developed into the 2019 FIGO classification (Table 1) for PAS disorders (47).

Table 1:

FIGO clinical classification for the diagnosis of PAS disorders at delivery.41

| GRADE 1 | Abnormally adherent placenta (PLACENTA ADHERENTA OR CRETA) |

If laparotomy is required

| |

| Histologic criteria |

|

| GRADE 2 | Abnormally invasive placentation (PLACENTA INCRETA) |

| Clinical criteria | At laparotomy

|

| Histologic criteria | Hysterectomy specimen or partial myometrial resection of the increta area shows placental villi within the muscular fibres and sometimes in the lumen of the deep uterine vasculature. |

| GRADE 3 | Abnormally invasive placentation (PLACENTA PERCRETA) |

| GRADE 3a | Limited to the uterine serosa |

| Clinical criteria | At laparotomy

|

| Histologic criteria | Hysterectomy specimen showing villous tissue within or breaching the uterine serosa |

| GRADE 3b | With urinary bladder invasion |

| Clinical criteria | At laparotomy

|

| Histologic criteria | hysterectomy specimen showing villous tissue breaching the uterine serosa and invading the bladder wall tissue or urothelium. |

| GRADE 3c | With invasion of other pelvic tissue/organs |

| Clinical criteria | At laparotomy

|

| Histologic criteria | Hysterectomy specimen showing villous tissue breaching the uterine serosa and invading pelvic tissues/organs. |

B. Histopathologic

Until the 1970s, the diagnosis of PAS was almost exclusively histological (48,49). The main histopathological criterion used in recent clinical cohorts to confirm the diagnosis of PAS is the absence of decidual/Nitabuch layer the between the tip of anchoring villi and superficial myometrium as originally described by Irving and Hertig (1). This is an elusive and simplistic histological criterion for the diagnosis of PAS as such areas are found with increasing incidence with advancing gestation in pregnancies without evidence of PAS (50). It is also important to highlight that Irving and Hertig (1) did not have cases of invasive PAS in their series and thus their definition would only apply to abnormally adherent placenta, not to placenta increta or percreta.

Confirmation of the depth of villous invasion of the uterine myometrium in cases of PAS is essential to improve prenatal detection and clinical management strategies. However, most recent studies lack clear descriptions of the histological criteria used to define the different grades of PAS (29,30). This is surprising considering the high rates of caesarean hysterectomy in many studies and may reflect limited access to experienced perinatal pathologists. A summary of the few studies that do provide PAS grading indicate that the prevalence of both adherent and invasive PAS is not as high as previously reported (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution and prevalence of the different grades of PAS disorders in histopathology and prenatal diagnosis series (13) and population studies (30).

| Author (year) | Total No. of cases of PAS | No. of PC (%) | No. of PI (%) | No. of PP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histopathology studies (1966–1978) | 118 | 82 (69.5%) | 28 (23.7%) | 8 (6.8%) |

| Prenatal diagnosis studies (2000–2016) | 203 | 103 (50.7%) | 49 (24.2%) | 51 (25.1%) |

| Prevalence (PAS/births) | 1/2415 | 1/3865 | 1/15628 | 1/10949 |

PC= Placenta Creta (abnormally adherent); PI= Placenta Increta (abnormally invasive); PP= Placenta Percreta (abnormally invasive).

Dannheim et al. (52) recently proposed methods for gross dissection, microscopic examination and reporting of hysterectomy specimens containing PAS. Histopathologic diagnosis of PAS however, can be very difficult if the surgeon has attempted to remove the placenta, or impossible in cases of conservative management where the whole placenta is left in situ. Therefore, collaboration between the surgical team and pathologists to guide the sampling of the hysterectomy specimen is paramount to obtain accurate grading and extent of the villous invasion.

PRENATAL DIAGNOSIS

Prenatally unsuspected PAS is often associated with massive obstetric haemorrhage (MOH) due to attempts by the surgical team to remove the placenta manually from the uterine wall (52). In these cases, the total blood loss is increased two-fold and the need to give blood products is 86% compared to 57% when the placenta is left undisturbed (53). The risk of MOH is particularly high in invasive PAS due to involvement of the main branches of uterine arteries and the possible invasion of the bladder wall and surrounding pelvic vessels (41,54). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed that antenatal diagnosis of PAS reduces perioperative complication rates, particularly the risk of surgical bleeding (55). Imaging by a skilled operator using the modality of their choice (usually ultrasound) enables precise localization of the placenta and has become crucial in improving the management of PAS (56). However, recent population studies have shown that PAS remains undetected before delivery in half (53,57) to two-third of the cases (44). While antenatal diagnostic precision nears 90% in series from expert centres, recent series show that up to a third of cases of PAS are not diagnosed during pregnancy (58).

The first case of prenatal identification of a placenta accreta was performed by Sadovsky et al in 1967 using placentography with radioactive isotopes (59). Tabsh et al were the first to report in 1982 on prenatal grey scale ultrasound diagnosis of placenta increta (60). Since then more than 1200 cases of prenatal ultrasound diagnosis have been described in the international literature (29) and ultrasound imaging is considered as highly accurate when performed by a skilled operator (7). The absence of ultrasound findings does not preclude the diagnosis of PAS (especially abnormally adherent placenta) and clinical factors (CDs and placenta previa) remain important in identifying women at high-risk (7,8).

Numerous techniques have been added to grey-scale imaging over the years, including colour Doppler imaging (CDI) and three-dimensional (3-D) power Doppler sonography raising the sensitivity of ultrasound (20,56). However, the results of well conducted prospective cohort studies have shown that the sensitivity and specificity of grey-scale imaging alone in diagnosing for PAS are as high as 90% when performed by experienced operators (61,62). As with clinical studies, there has been wide heterogeneity in terminology and study designs used in the published reports on the prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of PAS (29). Standardized descriptions of ultrasound signs associated with PAS were recently proposed by the European Working Group on Abnormally Invasive Placenta (AIP) (63) and a reporting pro forma based on these was suggested by an AIP international expert group (64). Although there is good to excellent agreement between expert observers for the diagnostic accuracy of the individual signs (65), some artefacts are the consequence of myometrial damage due to prior CD and some signs are extremely rare. Use of a combination of signs increases the detection rate of ultrasound for PAS, in particular for placenta percreta (66).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used increasingly for the antenatal detection of PAS and has been reported to be useful in assessing the depth of myometrial and parametrial invasion (7,56). Recent systematic reviews have found that prenatal MRI is highly accurate in identifying disorders of invasive placentation and that ultrasound and MRI have comparable predictive parameters (67,68). However, a recent study found that MRI resulted in a change in diagnosis that could alter clinical management of PAS disorders in more than one third of cases, but when changed, the diagnosis was often incorrect (69).

Overall it is unclear if MRI improves the diagnosis of PAS beyond what can be achieved by trained ultrasound operators (7,8). MRI may be less operator-dependent but the cost and limited access to equipment and expert radiologists makes it impractical as a screening tool for PAS, in particular in early pregnancy (70). The implementation of standardized prenatal targeted ultrasound protocols in specialist centres for pregnant women with risk factors for PAS is associated with improved maternal and neonatal outcomes (71). However, placental imaging is not routinely taught during ultrasound and radiology training courses. The rise in the rates of CD and PAS highlights the need to develop training programs for sonographers and other operators providing mid-pregnancy ultrasound examination and to use targeted scanning protocols at national and international levels.

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

For the majority of specialists, the principal management strategy to prevent excessive bleeding is to leave the placenta in situ and perform a primary hysterectomy (PH) at delivery (71–74). In cases where suspicion of PAS is high during CD, most US obstetricians proceed with PH, with less than a third attempting conservative management (72–73). Similarly, a recent international survey of experts found that 61% opt for a primary PH with the placenta left in situ as their first-choice management approach (74). Controversies still exist among experts regarding optimal timing of delivery, use of adjunctive measures, and conservative (uterine-sparing) methods. Overall, there are no RCTs nor prospective well-controlled observational studies comparing surgical and conservative approaches for the same grade of PAS. Management strategies for PAS will vary depending on prenatal diagnosis, local surgical expertise and, more recently, access to a specialist multidisciplinary team (MDT). The different management strategies and supporting evidence have been recently reviewed by the RCOG (7), FIGO (76), ACOG and SMFM (8).

A. Surgical management

Planned preterm (34–35 weeks) caesarean hysterectomy with the placenta left in situ is the recommended management strategy for PAS by ACOG (8). Both general and regional anaesthetic techniques have been shown to be safe for surgical procedures required for the delivery of PAS (7). The choice of anaesthetic technique for CD for placenta praevia and PAS should therefore be made by the anaesthetist conducting the procedure and the woman should be informed of the possible need to convert from regional to general anaesthesia (76).

If the placenta is anterior and extending towards the level of the umbilicus, a midline skin incision is often needed to allow for a high upper-segment transverse uterine incision above the upper border of the placenta (76). A large extended transverse incision (Cherney or Maylard) can be used to avoid a vertical incision but there is limited data available on their use in the management of PAS (76).

Total PH is the preferred method of due to the potential risk of malignancy developing in the cervical stump, the need for regular cervical cytology and other associated problems such as bleeding or discharge (76). This is always necessary if invasive placental tissue has been seen within the cervix on prenatal imaging. Devascularization of the uterus laterally on both sides and clamping the uterus at the lowest possible point just below the edge of the placenta while sparing the ureters has been recently shown to reduce maternal bleeding morbidity (77). Unless there are significant concerns regarding the risk of malignancy the ovaries should always be left. However, oophorectomy is always a risk for example due to adhesions precluding safe separation or bleeding occurring proximal to the ovary.

Planned delayed or secondary hysterectomy is an alternative “definitive” surgical management strategy for PAS (7). Delayed hysterectomy may be necessary where extensive invasion (percreta) of surrounding structures would render immediate cesarean hysterectomy extremely difficult or if the diagnosis of PAS is made at the time of birth and the operating team has limited surgical experience in performing complex surgical procedures.

B. Conservative management

Planned PH may be unacceptable to women desiring to preserve their fertility, and conservative management techniques for uterine preservation for both adherent and invasive placenta accreta have been used increasingly in many centres around the world. These techniques include leaving the placenta in situ, partial myometrial resection of the accreta area with myometrial repair, and suturing around the accreta area (78). These methods have been used alone or in combination with additional procedures such as uterine artery devascularisation techniques either surgical or with interventional radiology (IR).

When the extent of the PAS area is limited in depth and can be entirely visualized (i.e. completely anterior, fundal or posterior without deep pelvic or cervical invasion) and is accessible a conservative uterus-preserving surgery may be appropriate. Partial myometrial resection can be attempted to allow a conservative management of the uterus (7,78). However, this should only be attempted by teams with experience and appropriate expertise to manage such cases conservatively (78).

There are no RCTs comparing the different conservative management techniques. Uterus-preserving surgical techniques are associated with a 16% unintentional urinary tract injury rate compared to 57% for standard hysterectomy and that use of ureteric stents reduces the risk of urologic injury (79). An increasing number of authors claim to have high success rates, sometime 100%, for uterine preservation surgery for PAS using compressive suture, intra-uterine balloon, uterine devascularization etc. (80–82). Although the retrospective design, small number of cases, lack of controls, absence of histopathological evidence and lack of standardized clinical or photographic evidence of PAS at birth considerably limits the value of their data (30). Specifically, it is impossible to reproduce such results in other centers or populations, or carry out meaningful meta-analysis unless a clear, clinical definition of the severity of PAS encountered is described. For these reasons, FIGO have developed a standardized clinical classification for PAS that clearly defines features of any given case (Table 1) and can be corroborated with histopathology where available.

C. Additional therapeutic techniques

There are no RCTs on the use of ureteral stents in PAS. Ureteral stents or catheters are more commonly used in the US where 26% of ACOG fellows are using them in the management of PAS (74) but there are currently insufficient data to recommend the routine use of ureteric stents in PAS.

Interventional radiology (IR) including intraoperative internal iliac artery and/or postoperative uterine artery embolisation and internal iliac artery or abdominal balloon occlusion has been proposed to reduce bleeding in women at high risk of perioperative and post-partum hemorrhage. A systematic review has reported success rates of around 90% for arterial embolisation in PAS, with secondary PH being necessary in 11.3% (78). Arterial balloon occlusion catheters have been associated with a success rate of nearly 70% but the use of prophylactic placement of balloon catheters in the iliac arteries in cases of PAS is still controversial, mainly because of the high risks of complications. A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis has shown that IR reduces the risks of bleeding during surgery but the studies were heterogenous and of very low quality (84). A small RCT preoperative prophylactic balloon catheters versus controls of women presenting with a prenatal diagnosis of PAS found no difference in blood loss >2500 ml, number of plasma products transfused, duration of surgery, peripartum complications and hospital stay (85). Some argue that the vast collateral blood supply to the gravid uterus, and particularly to the invasive placenta may require higher vascular occlusion, such as at the infra-renal aorta, to significantly reduce blood loss during surgery for PAS. Larger, higher quality studies are necessary to determine the safety and efficacy of IR before this technique can be advised in the routine management of PAS (7).

Internal iliac artery ligation was first described by surgeons at the beginning of the 20th century and used in obstetrics to reduce the risks of post-partum hemorrhage before the advent of IR. In low-resources countries, where IR is not available it has remained in use in particular in the context of uterine preservation in PAS. A recent RCT of bilateral internal iliac artery ligation (n= 29 cases) versus controls (n= 28 cases) reported no significant difference between the two groups regarding the intraoperative estimated blood loss (86).

D. Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) approach

A recent observational study of obstetric-led units in England found that 70% manage their PAS cases “in-house”, despite one third of these units reporting that they only treat one or fewer cases each year (87). However, there is mounting evidence that women with PAS diagnosed prenatally and managed by an MDT in a centre of excellence are less likely to require emergency surgery, large-volume blood transfusion and reoperation within 7 days of delivery for bleeding complications compared with women managed by standard obstetric care without a specific protocol (38,88,89). In addition, women with PAS admitted at 34 weeks of gestation and delivered between 34 and 35 weeks of gestation by a specialist MDT have a significantly lower emergency surgery rate than those not cared for by such a team despite a similar median gestational age at delivery. These studies have also shown that maternal outcomes are improved over time with increasing experience within a well-established MDT performing 2–3 cases per month. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis has confirmed these findings but has also highlighted that all the studies included in the review are retrospective (90). Furthermore, these studies provide no data on the differential clinical diagnosis between abnormally adherent and abnormally invasive PAS nor detailed pathologic confirmation of the depth and lateral extension of villous myometrial invasion. There is therefore a need for more prospective studies with detailed clinical and histopathologic data.

CONCLUSION

Accreta placentation is a potentially life-threatening condition. The incidence of PAS will predictably increase further over time, if modern obstetric caesarean delivery trends continue. It is therefore, incumbent on all healthcare providers to systematically improve upon the recognition of risk factors, the accuracy of antenatal diagnosis, and the intrapartum management for women with PAS.

MCQs

-

1The following is true about the diagnostic accuracy of antenatal imaging for PAS:

- Magnetic resonance imaging is superior to ultrasound in detecting PAS in most cases.

- Ultrasound detects PAS prenatally in approximately 50% of cases in population-based studies, but may detect PAS with up to 90% accuracy in expert centres.

- Antenatal imaging provides a highly objective screening tool which negates the need for clinical information or history to accurately identify PAS.

- A standardised approach to placental imaging is included in routine training for sonographers.

a= F; b= T; c= F; d= F

Explanation to the answers for Question 1:

The sensitivity and specificity of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound (US) for the identification of PAS are similar, when images are performed and interpreted by experienced providers. False positive and false negative diagnosis may occur with either imaging modality, therefore diagnostic parameters are relatively equivalent. MRI is expensive, and clear benefit has not been sufficiently demonstrated to recommend it be used as a primary screening tool, however it may be used as an adjunctive imaging modality in cases in which the placenta is not fully or adequately visualised on ultrasound.

In two large population-based studies, one from the U.K and one from the U.S., antenatal detection of PAS occurred in approximately 50% of cases. Multiple studies from expert centres report diagnostic sensitivity and specificity approaching 90%.

Antenatal imaging provides objective data, however in studies comparing the diagnostic accuracy using imaging alone, clinial factors and history alone, or imaging and history in combination, clinical factors, and antenatal diagnosis improved with inclusion of clinical information. Elicitation of clinical risk factors may alert the sonographer or imaging provider to look for subtle findings suggestive of PAS.

Currently, most sonographers are instructed that they must assess the placenta, however the approach to placental imaging that is taught is highly variable, and dependent upon the skill and interest of the instructor. There is a great need to standardise and optimize instructional programs to ensure sonographers recognise and obtain images necessary to accurately iidentify PAS.

-

2The following conditions combined comprise the risk factors most commonly identified in women with PAS:

- Advanced maternal age and previous hysteroscopic surgery

- In vitro fertilization with a prior history of primary infertility

- Placenta previa and prior cesarean deliveries

- History of myomectomy and obesity

a =F; b= F; c= T; d= F

Explanation to the answers for Question 2:

Advanced Maternal Age is a risk factor for PAS, however the actual contribution of age alone is unknown, and currently likely low. When placenta accreta was first described in the 1930s, advanced maternal age and grand multiparity were commonly described. Deliveries. History of hysteroscopic surgery may also be a risk factor, however, it is more likely to contribute risk if a large resection or injury to the myometrium occurred.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) has been shown to increase the risk for PAS by between 4- to 13-fold, especially when cryopreserved embryos are used. Because women who undergo IVF or have primary infertility are less likely to have had prior pregnancies than women without primary infertility, the overall rate of women with PAS due only to IVF and primary infertility remains a minority

Prior caesarean deliveries, especially multiple prior cesarean deliveries combined with a placenta previa are the most common risk factors for development of PAS. Currently, cesarean delivery is one of the most commonly performed surgeries in developed countries, and cesarean rates have risen worldwide in the last several decades.

Myomectomy has been associated with the risk for PAS in case reports and cohort studies of placenta accreta spectrum, especially if the endometrial cavity was breached at the time of fibroid removal. One secondary analysis of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Networks Cesarean Delivery dataset showed no increased risk for PAS in women who reported a history of myomectomy, however this study was not powered to detect PAS in women with myomectomy, nor was the database specific to either PAS or myomectomy. Obesity has not been shown, to date, to be a risk factor for accreta.

-

3The following is true regarding the current state of scientific studies of PAS:

- There is a lack of well-designed, prospective, randomised controlled trials to guide diagnosis and management of PAS, and standardization of terminology used in studies is recommended.

- Comparative studies have demonstrated superiority of conservative management of PAS over local myometrial resection.

- Although PAS represents a spectrum of placental invasion, the morbidity and severity of complications across the placenta accreta spectrum are sufficiently similar that meaningful meta-analysis can be done with studies that have already published.

- Delivery in expert centres with multidisciplinary teams has not been shown to reduce blood loss or the need for blood products at the time of delivery.

a =T; b= F; c= F; d= F

Explanation to the answers for Question 3:

A majority of studies regarding PAS are retrospective, not well-controlled, and lack clear, standardised definitions of the extent and depth of placental invasion. Almost no randomised controlled trials have been conducted.

No studies have been published to date that directly compare various methods of conservative management of PAS. While both leaving the placenta in situ and using adjunctive measures and local resection of the affected myometrium have been shown to be possible and safe in several cases, there is no clear superiority, and the risks of each approach differ and must be considered in management and planning.

Standardised, detailed information about the extent and depth of invasion, criteria used to determine degree of invasion, clinical and histological findings are notably lacking in a vast majority of studies published to date. Drawing meaningful conclusions with meta-analysis depends upon, and ensuring that the data included is clear, well-defined and on reducing heterogeneity. The wide variety of terminology, diagnostic criteria used for diagnosis and reporting obscures currently available data.

Delivery in expert centres with multidisciplinary teams has been shown to reduce blood loss and the need for transfusion by as much as 50% in some studies, and has been shown to improve outcomes even when surgeries are performed urgently/emergently due to bleeding, or when the diagnosis was not anticipated prior to delivery.

-

4The following is true regarding the FIGO clinical classification for the diagnosis of PAS disorders (Table 1):

- Classification using the FIGO system requires histologic evaluation of the placenta and myometrium.

- The FIGO classification system ranges from Grade 1 to Grade 5 with the severity of invasion increasing as the number increases

- Grade 2 describes cases of placenta adherenta or accreta within the placenta accreta spectrum

- Grade 3 includes all cases of placenta percreta, with 3a including invasion beyond the serosa, but no invasion of other organs, 3b including invasion into the bladder wall or urothelium and 3b including invasion into the parametrium or any other organ, with or without bladder invasion.

a= F; b= F; c= F; d= T

Explanation to the answers for Question 4:

The FIGO classification system relies upon clinical findings at the time of delivery, in order to include cases that are managed conservatively, and in which the placenta is left in situ. If histopathology is available, it may be used in staging, but it is not required.

The FIGO Classification system ranges from Grade 1 to Grade 3. Grade 3 is further divided into Grade 3a, 3b and 3c.

Grade 1 describes cases that are consistent with previous descriptions of placenta adherenta or accreta. Grade 2 more closely represents placenta increta within the spectrum.

Grade 3 includes placenta percreta, with 3a including invasion beyond the serosa, but no invasion of other organs, 3b including invasion into the bladder wall or urothelium and 3b including invasion into the parametrium or any other organ, with or without bladder invasion.

Highlights for review.

Caesarean delivery rates (CD) and placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) prevalence have increased in parallel

A low-lying/placenta previa and a history of prior CD is associated with the highest risk of PAS

Specialist centres with multidisciplinary expertise are essential to the management of PAS

The lack of standardised protocols for the diagnosis of PAS at birth undermines the value of clinical data.

PRACTICE POINTS.

Increased caesarean delivery rates (CD) have been the main epidemiological factor in the increase in prevalence placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) and this phenomenon has been observed in both high-income and low-income countries.

Women presenting with a low-lying/placenta previa and a history of prior CD are the group with the highest risk of PAS and there is a need to identify them antenatally to plan a management approach tailored to their individual need.

The lack of standardised protocols for the diagnosis of PAS at birth undermines the value of clinical data in particular in the evaluation of the epidemiology of the different grades of PAS and the outcome of different management strategies.

The development of specialist centres with multidisciplinary expertise in management of complex obstetric surgery with access to adult and neonatal intensive care and blood transfusion that perform at least 2 cases per month are essential to improve the management and outcome of invasive PAS.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

The views expressed in this document reflect the opinion of the individuals and not necessarily those of the institutions that they represent.

REFERENCES

- 1.Irving C, Hertig AT. A study of placenta accreta. Surgery, Gynecol Obstet 1937;64:178–200. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langhans T Die losung der muetterlichen eihaeute. Arch F Gynaek. 1875;8:287–97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart DB. A contribution to the pathology symptoms and treatment of adherent placenta. Edinburgh Med J. 1889,34:816–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baisch K Zur pathologischen anatomie der placenta accreta. Arb Geb Pathol Anat Bact. 1907–1908;6:265–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5. *.Luke RK, Sharpe JW, Greene RR Placenta accreta: The adherent or invasive placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1966;95:660–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jauniaux E, Ayres-de-Campos D; FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Introduction. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. *.Jauniaux E, Alfirevic Z, Bhide AG, Belfort MA, Burton GJ, Collins SL et al. ; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Placenta Praevia and Placenta Accreta: Diagnosis and Management: Green-top Guideline No. 27a. BJOG. 2019;126:e1–e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. *.Obstetric Care Consensus No. 7 Summary: Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1519–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forster DS. A case of placenta accreta. Can Med Assoc J. 1927;17:204–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kearns PJ. Placenta increta. Can Med Assoc J. 1931;25:198–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munro Kerr JM. Indications for Caesarean Section. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 1921;28:338–48. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland E Methods of Performing Caesarean Section. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 1921; 28: 349–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13. *.Jauniaux E, Chantraine F, Silver RM, Langhoff-Roos J; FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Epidemiology . Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boerma T, Ronsmans C, Melesse DY, Barros AJD, Barros FC, Juan L et al. Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections. Lancet. 2018;392:1341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurol-Urganci I, Cromwell DA, Edozien LC, et al. Risk of placenta previa in second birth after first birth cesarean section: a population-based study and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. The association of placenta previa with history of cesarean delivery and abortion: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1071–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall NE, Fu R, Guise JM. Impact of multiple cesarean deliveries on maternal morbidity: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:262e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Thom EA et al. ; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1226–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzpatrick KE, Sellers S, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P, Knight M. Incidence and risk factors for placenta accreta/increta/percreta in the UK: a national case-control study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jauniaux E, Bhide A. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis and outcome of placenta previa accreta after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brookfield KF, Goodnough LT, Lyell DJ, Butwick AJ. Perioperative and transfusion outcomes in women undergoing cesarean hysterectomy for abnormal placentation. Transfusion. 2014;54:1530–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green L, Knight M, Seeney FM, Hopkinson C, Collins PW, Collis RE, Simpson N, Weeks A, Stanworth SS. The epidemiology and outcomes of women with postpartum haemorrhage requiring massive transfusion with eight or more units of red cells: a national cross-sectional study. BJOG. 2015;123:2164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solheim KN, Esakoff TF, Little SE, Cheng YW, Sparks TN, Caughey AB. The effect of cesarean delivery rates on the future incidence of placenta previa, placenta accreta, and maternal mortality. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:1341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight M, Nair M, Tuffnell D, Shakespeare J, Kenyon S, Kurinczuk JJ (Eds.) on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care – Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2013–15. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; 2017. [www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk]. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D. Placenta accreta: pathogenesis of a 20th century iatrogenic uterine disease. Placenta. 2012;33:244–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baldwin HJ, Patterson JA, Nippita TA, Torvaldsen S, Ibiebele I, Simpson JM, Ford JB. Antecedents of abnormally invasive placenta in primiparous women: risk associated with gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Gilbert S, Landon MB, Spong CY, Rouse DJ, Varner MW et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Risk of uterine rupture and placenta accreta with prior uterine surgery outside of the lower segment. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1332–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balayla J, Bondarenko HD. Placenta accreta and the risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Perinat Med. 2013;41:141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. *.Jauniaux E, Collins SL, Jurkovic D, Burton GJ Accreta placentation. A systematic review of prenatal ultrasound imaging and grading of villous invasiveness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 215:712–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. *.Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Grønbeck L, Langhoff-Roos J Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;220: doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.01.233.[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jauniaux E, Bhide A, Burton GJ. Pathophysiology of accreta In: Silver R, ed. Placenta accreta syndrome. Portland: CRC Press, 2017:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jauniaux E, Burton GJ. Pathophysiology of Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Current Findings. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61:743–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gielchinsky Y, Rojansky N, Fasouliotis SJ, Ezra Y. Placenta accreta--summary of 10 years: a survey of 310 cases. Placenta. 2002;23:210–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheiner E, Levy A, Katz M, Mazor M. Identifying risk factors for peripartum cesarean hysterectomy. A population-based study. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:622–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bencaiova G, Burkhardt T, Beinder E. Abnormal placental invasion experience at 1 center. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:709–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodring TC, Klauser CK, Bofill JA, Martin RW, Morrison JC. Prediction of placenta accreta by ultrasonography and color Doppler imaging. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:118–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klar M, Laub M, Schulte-Moenting J, Proempeler H, Kunze M. Clinical risk factors for complete and partial placental retention: a case-control study. J Perinat Med. 2014;41:529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, Abuhamad AZ, Simhan H, Huls CK, Belfort MA, Wright JD. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:561–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Acar A, Ercan F, Pekin A, Elci Atilgan A, Sayal HB, Balci O, Gorkemli H. Conservative management of placental invasion anomalies with an intracavitary suture technique. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143:184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng Q, Zhang W, Liu Y. Clinical application of stage operation in patients with placenta accreta after previous caesarean section. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e10842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcellin L, Delorme P, Bonnet MP, Grange G, Kayem G, Tsatsaris V et al. Placenta percreta is associated with more frequent severe maternal morbidity than placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:193.e1–193.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei Y, Cao Y, Yu Y, Wang Z. Evaluation of a modified “Triple-P” procedure in women with morbidly adherent placenta after previous caesarean section. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296:737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehrabadi A, Hutcheon JA, Liu S, Bartholomew S, Kramer MS, Liston RM, et al. ; Maternal Health Study Group of Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System (Public Health Agency of Canada). Contribution of placenta accreta to the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage and severe postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:814–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. *.Thurn L, Lindqvist PG, Jakobsson M, Colmorn LB, Klungsoyr K, Bjarnadóttir RI, et al. Abnormally invasive placenta-prevalence, risk factors and antenatal suspicion: results from a large population-based pregnancy cohort study in the Nordic countries. BJOG. 2016;123:1348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colmorn LB, Krebs L, Klungsøyr K, Jakobsson M, Tapper AM, Gissler M, et al. Mode of first delivery and severe maternal complications in the subsequent pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:1053–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins SL, Stevenson GN, Al-Khan A, Illsley NP, Impey L, Pappas L, et al. Three-Dimensional Power Doppler Ultrasonography for Diagnosing Abnormally Invasive Placenta and Quantifying the Risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:645–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. *.Jauniaux E, Ayres-de-Campos D, Langhoff-Ross J, Fox KA, Collins SL, FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO classification for the clinical diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum disorders Int J Gynecol Obstet 2019;142: in press (Feb). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weekes LR, Greig LB. Placenta accreta: A twenty-year review”. Am J Obstet Gynecol.1972;113:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Breen JL, Neubecker R, Gregori CA, Franklin JE Jr. Placenta accreta, increta, and percreta. A survey of 40 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;49:43–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. *.Jauniaux E, Collins SL, Burton GJ Placenta accreta spectrum: Pathophysiology and evidence-based anatomy for prenatal ultrasound imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dannheim K, Shainker SA, Hecht JL. Hysterectomy for placenta accreta; methods for gross and microscopic pathology examination. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:951–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silver RM, Branch DW. Placenta Accreta Spectrum. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1529–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fitzpatrick K, Sellers S, Spark P, Kurinczuk J, Brocklehurst P, Knight M. The management and outcomes of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta in the UK: a population-based descriptive study. BJOG 2014;121:62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hubinont C, Mhallem M, Baldin P, Debieve F, Bernard P, Jauniaux E. A clinico-pathologic study of placenta percreta. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:365–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buca D, Liberati M, Calì G, Forlani F, Caisutti C, Flacco ME et al. Influence of prenatal diagnosis of abnormally invasive placenta on maternal outcome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52:304–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jauniaux E, Bhide A, Kennedy A, Woodward P, Hubinont C, Collins S; FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Prenatal diagnosis and screening. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bailit JL, Grobman WA, Rice MM, Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Varner MW, , et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network. Morbidly adherent placenta treatments and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:683–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Bardsley TR, Greene T, Varner MW, Silver RM. Risk Factors for Placenta Accreta: A Large Prospective Cohort. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sadovsky E, Palti Z, Polishuk WZ, Robinson E. Atypical placentography in placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 1967;29:784–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tabsh KM, Brinkman CR 3rd, King W. Ultrasound diagnosis of placenta increta. J Clin Ultrasound. 1982;10:288–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Finberg HJ, Williams JW. Placenta accreta: prospective sonographic diagnosis in patients with placenta previa and prior cesarean section. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:333–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Comstock CH, Love JJ Jr, Bronsteen RA, Lee W, Vettraino IM, Huang RR, et al. Sonographic detection of placenta accreta in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. *.Collins SL, Ashcroft A, Braun T, Calda P, Langhoff-Ross J, Morel O et al. , Proposed for standardized ultrasound descriptions of abnormally invasive placenta (AIP). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alfirevic Z, Tang A-W, Collins SL, Robson SC, Palacios-Jaraquemadas, on behalf of the Ad-hoc International AIP Expert group. Pro forma for ultrasound reporting in suspected abnormally invasive placenta (AIP); an international consensus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:276–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zosmer N, Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Panaiotova J, Shaikh H, Nicholaides KH. Interobserver agreement on standardized ultrasound and histopathologic signs for the prenatal iagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum disorder. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018:140:326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cali G, Forlani F, Timor-Trisch I, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Foti F, Minneci G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound in detecting the depth of invasion in women at risk of abnormally invasive placenta: A prospective longitudinal study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:1219–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meng X, Xie L, Song W. Comparing the diagnostic value of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging for placenta accreta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013;39:1958–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Familiari A, Liberati M, Lim P, Pagani G, Cali G, Buca D, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in detecting the severity of abnormal invasive placenta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:507–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Einerson BD, Rodriguez CE, Kennedy AM, Woodward PJ, Donnelly MA, Silver RM. Magnetic resonance imaging is often misleading when used as an adjunct to ultrasound in the management of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:618.e1–618.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Panaiotova J, Tokunaka M, Krajewska K, Zosmer N, Nicolaides KH. Screening for morbidly adherent placenta in early pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Melcer Y, Jauniaux E, Maymon S, Tsviban A, Pekar-Zlotin M, Betser M, Maymon R. Impact of targeted scanning protocols on perinatal outcomes in pregnancies at risk of placenta accreta spectrum or vasa previa. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:443.e1–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.O’Brien JM, Barton JR, Donaldson ES. The management of placenta percreta: conservative and operative strategies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1632–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Esakoff TF, Handler SJ, Granados JM, Caughey AB. PAMUS: placenta accreta management across the United States. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:761–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wright JD, Silver RM, Bonanno C, Gaddipati S, Lu YS, Simpson LL, et al. Practice patterns and knowledge of obstetricians and gynecologists regarding placenta accreta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:1602–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cal M, Ayres-de-Campos D, Jauniaux E. International survey of practices used in the diagnosis and management of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Allen L, Jauniaux E, Hobson S, Papillon-Smith J, Belfort MA; FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Nonconservative surgical management. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:281–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hussein AM, Kamel A, Raslan A, Dakhly DMR, Abdelhafeez A, Nabil M, Momtaz M. Modified cesarean hysterectomy technique for management of cases of placenta increta and percreta at a tertiary referral hospital in Egypt. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-5027-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sentilhes L, Kayem G, Chandraharan E, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Jauniaux E; FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Conservative management. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mei J, Wang Y, Zou B, Hou Y, Ma T, Chen M, Xie L. Systematic review of uterus-preserving treatment modalities for abnormally invasive placenta. J Obstet Gynaecol 2015;35:777–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tam Tam KB, Dozier J, Martin JN Jr. Approaches to reduce urinary tract injury during management of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:329–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wolf MF, Maymon S, Shnaider O, Singer-Jordan J, Maymon R, Bornstein J, et al. Two approaches for placenta accreta spectrum: B-lynch suture versus pelvic artery endovascular balloon. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;18:1–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ratiu AC, Crisan DC. A prospective evaluation and management of different types of placenta praevia using parallel vertical compression suture to preserve uterus. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e13253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Acar A, Ercan F, Pekin A, Elci Atilgan A, Sayal HB, Balci O et al. Conservative management of placental invasion anomalies with an intracavitary suture technique. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143:184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.D’Antonio F, Iacovelli A, Liberati M, Leombroni M, Murgano D, Cali G, et al. Role of interventional radiology in pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1002/uog.20131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Salim R, Chulski A, Romano S, Garmi G, Rudin M, Shalev E. Precesarean prophylactic balloon catheters for suspected placenta accreta: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:1022–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hussein AM, Dakhly DMR, Raslan AN, Kamel A, Abdel Hafeez A, Moussa M, et al. The role of prophylactic internal iliac artery ligation in abnormally invasive placenta undergoing caesarean hysterectomy: a randomized control trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1–7. Doi 10.1080/14767058.2018.1463986. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sargent W, Collins SL. Are women antenatally diagnosed with abnormally invasive placenta receiving optimal management in England? An observational study of planned place of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019; doi: 10.1111/aogs.13487. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, Diaz-Arrastia CR, Lee W, Baker BW, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:218.e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Erfani H, Clark SL, Salmanian B, Baker BW et al. , Multidisciplinary team learning in the management of the morbidly adherent placenta: outcome improvements over time. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:612.e1–612.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bartels HC, Rogers AC, O’Brien D, McVey R, Walsh J, Brennan DJ. Association of Implementing a multidisciplinary team approach in the management of morbidly adherent placenta with maternal morbidity and mortality. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]