Abstract

RNA molecules (e.g., siRNA, microRNA, and mRNA) have shown tremendous potential for immunomodulation and cancer immunotherapy. They can activate both innate and adaptive immune system responses by silencing or upregulating immune-relevant genes. In addition, mRNA-based vaccines have recently been actively pursued and tested in cancer patients, as a form of treatment. Meanwhile, various nanomaterials have been developed to enhance RNA delivery to the tumor and immune cells. In this review article, we summarize recent advances in the development of RNA-based therapeutics and their applications in cancer immunotherapy. We also highlight the variety of nanoparticle platforms that have been used for RNA delivery to elicit anti-tumor immune responses. Finally, we provide our perspectives of potential challenges and opportunities of RNA-based nanotherapeutics in clinical translation towards cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: RNA, nanoparticle, immunotherapy, cancer, RNAi, CRISPR

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, RNA-based therapeutics, such as messenger RNA (mRNA), microRNA, and small interfering RNA (siRNA), have emerged as highly attractive classes of drugs for the treatment and prevention of numerous diseases (e.g., cancers, genetic disorders, diabetes, inflammatory diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases)1-6. In comparison to the conventional small molecular drugs or proteins (specifically antibodies), RNA therapeutics can play remarkable regulatory roles in the treatment of targeted cells by either increasing the expression of a given protein or knocking out targeted genes to some varying degree. In addition to these regulatory roles, the fact that they are more convenient and easier to design than protein-based drugs, is what makes RNA therapeutics such an appealing form of treatment to researchers. However, the instability of RNAs themselves and the presence of various physiological barriers that inhibit the delivery and transfection of RNAs are what hinder their clinical application in cancer therapy 7, 8. Moreover, the exogenous RNA is more likely to be cleared by the human body's intrinsic defense systems, e.g., various exonucleases and RNases responsible for RNA degradation, the major organs or tissues (e.g., kidneys and liver), and the innate immune system for RNA clearance 3, 9. To overcome such immunogenic hurdles and make sure safe delivery of these RNA therapeutics to their target sites occurs, nanoparticle-based delivery systems have been explored as potential RNA delivery tools for in vitro and in vivo applications 10, 11.

Since the clinical success of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)12 and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies13, 14, cancer immunotherapy treatments have drawn increasing interests. In contrast to chemotherapeutic drugs with dose-limited toxicities and potential development of drug-resistance by tumor cells, immunotherapeutics can inhibit the ability of tumor cells to evade termination by the immune system or re-program cancer-associated immune systems, and are thus more specific and able to trigger long-lasting memory anti-tumor responses. Despite these desirable features and research breakthroughs, currently used ICB antibodies and cell-based therapeutics (e.g., CAR-T) in tumor immunotherapy are far from perfect, and it is imperative to pursue new strategies for improving their safety and efficacy 15-17. RNA-based therapeutics have many potential uses in immunomodulation and cancer immunotherapy, such as silencing immune checkpoint genes, activating the innate or adaptive immune system by regulating cytokines expressions, and acting as tumor antigen vaccines18, 19. The use of RNA-based therapeutics has recently expanded dramatically, and some have been moved to clinical trial studies during the past decade, revealing these genetic materials as excellent candidates for cancer treatment. Meanwhile, the development of various nanoparticle-based platforms, such as liposomes 20, polymeric nanoparticles (NPs)21-26, and inorganic NPs27, 28 for efficient delivery of RNAs provides a bright future for RNA-based therapeutics and their applications in cancer immunotherapy.

In this review article, an overview of RNA-based nanotherapeutics and recent advances, including their delivery nanoplatforms and applications in tumor immunotherapy, will be presented. Also, the various nanomaterials that have been used to deliver RNAs to tumor cells or immune cells for the induction of anti-tumor immune responses, will be highlighted. Finally, the current challenges of RNA-based nanotherapeutics will be discussed and the potential clinical value of RNA-based nanotherapeutics in tumor immunotherapy will be highlighted.

2. Nanotechnology for delivery of therapeutic RNAs

2.1 RNA therapeutics

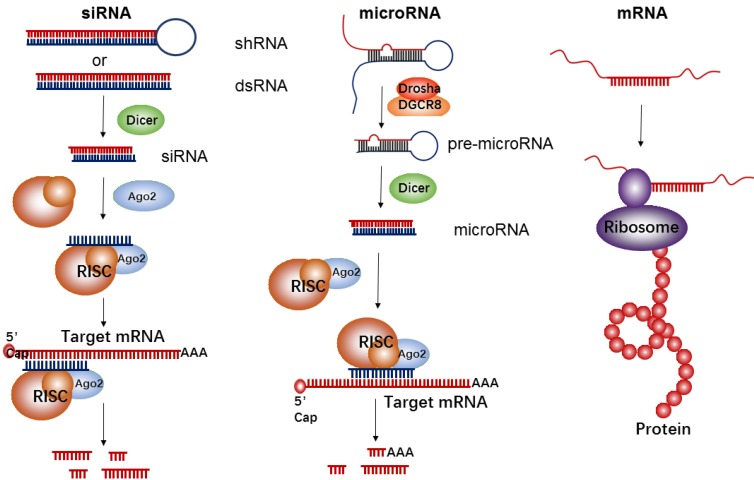

RNA-based therapeutics have demonstrated a wide array of promising applications in the field of cancer treatment. They function as either inhibitors (e.g., siRNA and microRNA) or upregulators (e.g., mRNA) of target protein expression (Figure 1). siRNA is double-stranded in nature and approximately 22 nucleotides in length. Its precursor is initially recognized by Dicer RNase and is then incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The siRNA-RISC complex can bind the targeting site of mRNA, and lead to a sequence-specific cleavage by endonuclease Argonaute-2 (AGO2), thus decreasing expressions of a targeted protein 29. MicroRNA is another common short regulatory noncoding RNA, used for blocking target gene expression via binding to target sites in the 3'-untranslated regions (UTR) of protein-coding transcripts 30. Firstly, primary microRNA (pri-microRNA) with a characteristic hairpin structure is recognized and processed by enzymes of Drosha and DGCR8 into ∼70 nt precursor microRNA (pre-microRNA). The resultant pre-microRNA is further cleaved by Dicer RNase, thus resulting in the formation of a mature dsRNA (microRNA). The mature microRNA is finally incorporated into RISC to induce cleavage of targeted mRNA, such as siRNAs, or translational repression, which induces a decrease of targeted proteins. Generally, the target sequences of the microRNA are frequently found in the 3' UTR of mRNA and can often be found within non-coding or intronic regions. Therefore, each microRNA can be capable of targeting hundreds of unique mRNAs and inducing regulation of the transcriptome. However, in comparison to microRNA's multi-mRNA targeting abilities, siRNA has specific binding activity; therefore, each siRNA can only bind one mRNA target.

Figure 1.

The biological mechanism of siRNA, microRNA, and mRNA for inhibition of target protein expressions or up-regulation of a given protein.

The goal of mRNA delivery is to upregulate targeted protein expressions like DNA delivery, but in contrast to DNA, mRNA therapeutics have several unique features, such as the absent risk of insertional mutagenesis, more consistent and predictable kinetics of protein expression, and relatively convenient in vitro synthesis31. Meanwhile, the transfection efficiency with mRNA is higher than that of DNA, especially in immune cells32-34. Each mRNA has an open reading frame (ORF) that includes two untranslated regions (UTRs) located at the 5' and 3' ends of mRNA, with the purpose of being recognized by the translational machinery (Ribosome). In addition to those UTRs, the mRNA's 5' methyl cap and 3' poly(adenosine) tail are also crucial for efficient translation35.

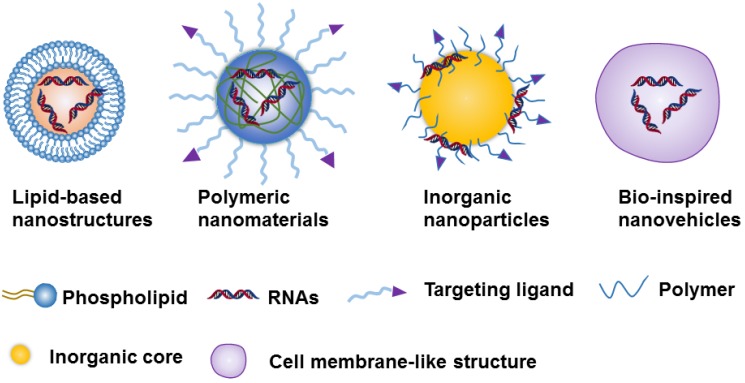

2.2 Nanocarriers for RNA delivery

Due to the challenges of naked RNA molecules for in vivo applications, i.e., extremely short half-lives (e.g., minutes), poor chemical stability, and easy degradation by nucleases18, 36, nanotechnology provides a versatile and targeted system for the safe delivery of them 37. The nanoparticle-based delivery systems not only protect RNA molecules from enzymatic degradation and immune system threats, but they also enable RNA accumulation to occur in the tumor site 35, 36. This RNA accumulation is able to occur due to the enhanced permeability and retention effect (EPR), which is a byproduct of the diameter of the NPs, which can range from 10 to 200 nm35, 36. Currently, the constituents of nanocarriers applied to RNAs delivery can be classified as lipid-based nanosystems 38-42, polymeric nanomaterials 43-45, inorganic nanoparticles 28, 46, 47 ,or Bio-inspired nanovehicles 48, 49 (Figure 2). We will here summarize these nanoparticle-based platforms and further discuss their strengths and potential drawbacks for RNA delivery (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the 4 nanoparticle-based platforms used in the RNA delivery.

Table 1.

Nanoparticle-based platforms for RNA delivery

| Nanocarriers | Classifications | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid-based nanostructures | Liposomes; solid lipid nanoparticles; lipid emulsions | Easy preparation, good biocompatibility and biodegradability | Limited stability, easy leakage of payloads, and rapid clearance |

| Polymer-based nanomaterials | Natural or naturally derived polymers: chitosan, poly-l-lysine, atelocollagen, etc. Synthetic polymers: PLGA, PEI, PVA, PLA, PEG, etc. |

Good biocompatibility and biodegradability for natural or naturally derived polymers, low cost of production, stimulation of drug release, easy modification | Nondegradable for some responsive polymers, dose-dependent toxicity |

| Inorganic NPs | MSNs, CNTs, QDs, and metal nanoparticles (e.g., iron oxide and gold nanoparticles) | Easy surface modification, good reproducibility, and easy cell uptake | Non-biodegradability, potential toxicity |

| Bio-inspired nano-vehicles | DNA-based nanostructures, exosome-mimetic nanovesicles, red blood cell member-based ghosts | Good biodegradability, low toxicity, strong targeting and low immune induction | High cost, stability concern |

2.2.1 Lipid-based nanostructures

Lipid-based nanostructures are one of the most commonly used non-viral delivery systems both in academic studies and clinical trials for chemotherapeutics or genetic drugs. Several classes of lipid-based nanocarriers including liposomes, lipid nanoemulsions, and solid lipid NPs have been used for RNA delivery 50. Generally, cationic lipids could be used as RNAs delivery carriers owing to their positively charged motif that has a strong interaction with negatively charged nucleic acids. As the lipids and phospholipids are the basic units of the cell membrane, lipid-based nanostructures with the similar units have a natural tendency to interact well with the cells membrane and thereby facilitating cellular uptake of RNAs. Meanwhile, the obvious other advantages of lipid-based nanostructures, such as easy preparation, good biocompatibility and biodegradability, have led them to be a promising tool in the delivery of RNA-based therapeutics. However, there are also several issues, including limited stability, easy leakage of payloads, and rapid clearance by the kidneys or liver should be addressed before these lipid-based delivery systems are put to perform at clinical or in vivo levels.

2.2.2 Polymer-based nanomaterials

Polymer-based nanomaterials are well-studied systems for RNA delivery 51, which are classified into two major categories: natural or naturally derived polymers, and synthetic polymeric conjugates 43, 44. Natural or naturally derived polymers such as chitosan, which is composed of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine and d-glucosamine, poly-l-lysine, which consists of repeating units of lysine, and atelocollagen, occur in nature and are produced by all living organisms. The advantages of these nanoparticles are good biocompatibility and biodegradability, and low cost of production 52-54. Among the synthetic polymers, poly(dl-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), polyethyleneimine (PEI), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyethylene glycol (PEG), poly-l-lactic acid (PLA), etc., are the most common polymers used in delivery of RNAs due to their high stability, good biocompatibility and biodegradability 55-59. Meanwhile, it is important to note that these synthetic polymers are easy to functionalize with ligand bindings for targeting, and with responsive units that respond to chemical, biological, and physical stimuli for the controllable release of cargoes. However, some synthetic polymers (e.g., PLGA) could not be directly applied in RNA delivery due to no cationic units on them, thus leading to low electrostatic interaction between polymers and RNAs. One method to overcome this problem is modification with various cationic motifs (e.g., PEI) or co-assembly with cationic polymers into nanostructures, it is also noted that the most cationic units or polymers are nondegradable, which may be associated with potential toxicity issues 22.

2.2.3 Inorganic nanoparticles

Recently, various inorganic NPs, such as mesoporous silica nanomaterials (MSNs) 60-62, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) 63, quantum dots (QDs) 64, and metal nanostructures65 (e.g., iron oxide and gold NPs), are reported as carriers for delivery of RNAs. These inorganic NPs are synthesized by biodegradable polymers and inorganic particles. Consequently, the properties of these nanoparticles are easy to control, and their advantages include surface modification, good reproducibility, and easy cell uptake. However, the level of degradability of all of the inorganic materials has yet to be determined, and potential toxicity could be a problem 58. As a result, more extensive in vivo studies are still needed.

2.2.4 Bio-inspired nanovehicles

In recent studies, some bio-inspired nanovehicles, such as DNA-based nanostructures 66, 67, exosome-mimetic nanovesicles 68, 69, and red cell member-based ghosts 70 have been explored as gene and drug carriers to enhance delivery to targeted cells. The exosome is a bilayer membrane-coated vesicle secreted by cells, whose function is triggering intercellular communication by transferring payload mRNA, miRNA, or proteins from one cell to another. Studies have shown that these exosome nanovesicles exhibit good biodegradability, which can be attributed to their morphology and surface properties which are similar to those of natural cells. Originated from cell membrane proteins, cell membrane-based ghosts are another cell-derived nanovesicles, which possess identical physiochemical properties, such as topological/physiological activities. These cell membrane-based ghosts have a promising future in nanotechnology for a variety of biomedical applications, such as targeted delivery of RNA therapeutics, and tissue regeneration 71. In comparison to other drug delivery systems, the advantages of these bio-inspired nanovehicles are low toxicity, strong targeting abilities, and low immune response induction. However, the high cost of production and vesicle stability should be considered in further clinical applications.

3. RNA nanotherapeutics for tumor immunotherapy

Tumor immunotherapy can induce a synergistic killing effect on tumor cells through primarily targeting the immune system rather than the tumor cells themselves. Current immunotherapeutics, including antibodies, proteins, and engineered immune cells (e.g., CAR-T) are promising strategies for cancer treatment and some of them have been successful in clinical applications. However, these therapies still face some critical issues, such as insufficient efficacy (e.g., ICB has shown activity in approximately 15%-25% of patients 72), high costs and side-effect 15, 17. RNA-based agents provide some advantages in immunomodulation, such as high selectivity for silence or increased expression of specific targets and low risk of off-target hitting. Using RNA therapeutics in conjunction with nanomaterials is a valuable strategy to improve the efficacy of immunomodulation for cancer treatments. When used as partners in synergistic combinations, more efficient and personalized results will be reached, enabling the combination to compete with current immunotherapies already on the market.

3.1 Nanostructure-mediated siRNA delivery for immunotherapy

Recently, many approaches have demonstrated that silencing the crucial factors of tumor progression in cancer cells or knocking out/down the immunosuppressive genes in cancer 73 and cancer-associated immune cells can effectively induce an anti-tumor immune response 74, 75. Nanomaterials can act as Trojan horses by delivering siRNAs, for regulating the immune response, to cancer or immune cells 76, 77. Here, we summarize the potential siRNA targets in tumor or immune cells, as well as nanostructure delivery systems for siRNA-mediated immunotherapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of siRNA-based nanotherapeutics for tumor immunotherapy

| Cells | Nanocarriers | Targeted gene | Immunological effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor cells | PCL-PEG/PCL-PEI | PD-L1 | Checkpoint blockade | 78 |

| FA-PEI polymers | PD-L1 | Checkpoint blockade | 79 | |

| Acidity-Responsive Micelleplex | PD-L1 | Checkpoint blockade | 80 | |

| Acid-activatable micelleplex (PDPA based) | PD-L1 | Checkpoint blockade | 81 | |

| Au-CGKRK nanoconjugates | PD-L1, STAT3 | Anti-proliferation and checkpoint blockade | 82 | |

| Liposome-protamine-hyaluronic acid NPs | TGF-β | Decrease TGF-β and enhance the antigen-specific immune response | 83 | |

| ROS-responsive NPs | TGF-β | Modify the immunosuppress microenvironment | 84 | |

| HA-coated liposome | CD47 | Decrease immune escape of tumor cells | 85 | |

| Glutamine-functionalized branched polyethyleneimine | CD47 | Induce evasion of phagocytic clearance | 86 | |

| Chitosan lactate | CD-73 | Attenuate the immunosuppressive microenvironment of the tumor | 87 | |

| The extracellular vesicles (EVs) | β-catenin | Combo therapy with ICB | 88 | |

| T cells | Lipid-coated calcium phosphate (LCP) | PD-1 | Checkpoint blockade | 89 |

| PEG-PLA | CTLA-4 | Checkpoint blockade | 90 | |

| TAMs | Gold NPs | TNF-α | Silence pro-inflammatory cytokines | 91 |

| Gold NPs | VEGF | Reduce the recruitment of inflammatory TAMs | 92 | |

| Peptides NPs | CSF-1R | Elimination of M2-like TAMs | 93 | |

| DCs | Gold nanorods or GNRs-PEI |

IDO | Promote DCs maturation, and increase secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines | 94, 95 |

| Cationic lipid NPs | PD-L1, PD-L2 |

Checkpoint blockade | 96 | |

| PEI based NPs | PD-L1 | Induce immunosuppressive DCs to antigen-presenting cells | 97 | |

| PEI based NPs | IDO | Increase secretion of proinflammatory cytokines | 98 | |

| PEG-PLL-PLLeu polypeptide micelles | STAT3 | Induce DCs maturation and activation, elevate expressions of CD86 and CD40 and IL-12 production | 99 | |

| PLGA NPs | STAT3 | Induce DCs maturation and promote antigen cross-presentation | 100 | |

| Cationic lipid NPs | SOCS1 | Promote production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines | 101 | |

| PLGA NPs | SOCS1 | Enhance the production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines | 102 | |

| lipid envelope-type NPs | A20 | Enhance production of pro-inflammatory molecules after lipopolysaccharide stimulation | 103 | |

| Others | Lipid/PEG NPs | CCR2 | Prevent monocytes accumulation | 104 |

| PEG/MT/PC NPs | VEGF, PIGF | Anti-proliferation and reverse immune environment | 105 | |

| Chitosan NPs | Galectin-1 | Reduce polarization to M2 TAMs | 106 |

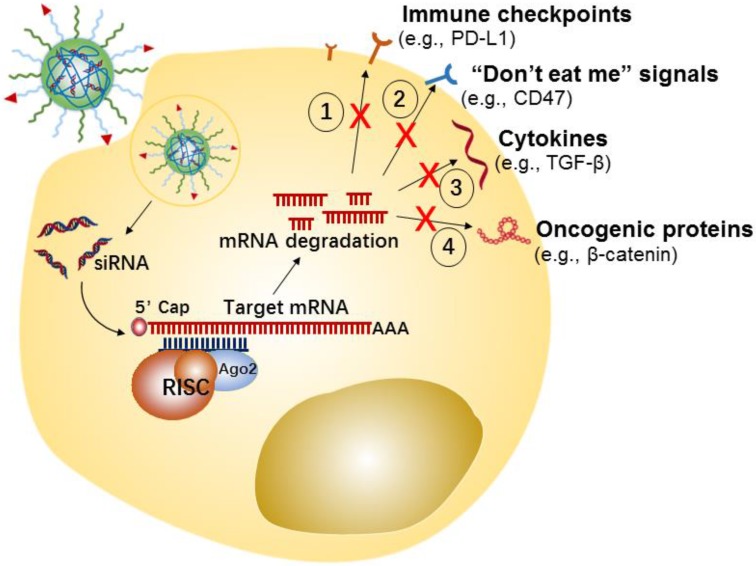

3.1.1 Tumor cells-targeted siRNA immunenanotherapy

Tumor cells can develop numerous strategies to promote immune system escape and drive the generation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment. For example, tumor cells can effectively induce and recruit distinct immunosuppressive cells, by promoting the secretion of some pro-tumor cytokines and chemokines107, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-10, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and C-X-C motif chemokine 5 (CXCL5). Meanwhile, the tumor-infiltrating suppressive cells evade immune surveillance by secreting or expressing a few immunosuppressive molecules that disrupt antigen presentation of dendritic cells (DCs) and suppress proliferation and activation of T cells 108, 109. Additionally, tumor cells could evade immunological eradication by downregulating antigen expression, and upregulating the expression of immune checkpoint proteins (e.g., PD-L1) or “don't eat me” signals (e.g., CD47) 110, 111. CD47 is over-expressed on the cancer cell surface, which enables escape from immune system recognition by labeling the cells with the “self” marker.

In the last few years, tumor cell-targeted siRNA nanotherapeutics have been centered on the downregulation of immune checkpoint proteins, “don't eat me” signals, anti-inflammatory cytokines, etc., for inducing anti-tumor immune-responses has been gaining increasing attention (Figure 3). For example, Yang et al. developed a systemic delivery strategy based on HA-coated Lipid NPs for delivery of CD47 siRNA to melanoma cancer cells, which induced an efficient knockdown of CD47 in cancer cells 85. CD47 silence effectively suppressed the tumor growth in a melanoma mice model. Similarly, using siRNA-based nanotherapy for the direct knockdown of immune checkpoints or anti-inflammatory cytokines on tumor cells has also enhanced anti-tumor immune responses and showed significant inhibition of tumor growth in vivo. For instance, Xu et al. developed a mannose-modified liposome-protamine-hyaluronic acid NPs (LPH) for encapsulating with TGF-β siRNA to B16F10 melanoma tumor cells 83. Meanwhile, the authors developed another lipid-calcium-phosphate NP (LCP) to deliver tumor antigens (i.e., Trp 2 peptide and CpG oligonucleotide) to the dendritic cells, with the purpose of eliciting a systemic immune response. The in vivo results displayed that silencing of TGF-β by LPH boosted the vaccination efficacy of LCP, and significantly inhibited tumor growth.

Figure 3.

Potential strategies of tumor cells-targeted siRNA nanotherapeutics for cancer immunotherapy.

The exciting anti-tumor effect produced by the combination of two NPs suggested the combo therapy by two or more therapeutics will induce a more powerful anti-tumor immune response and offer a powerful platform for cancer treatment. Based on this, some strategies that combine RNA-based nanotherapeutics with photodynamic or chemical agents are being reported in recent studies 80, 81. For instance, Dai et al. reported a pH-responsive nanosystem that when co-loaded with PD-L1 siRNA and a mitochondrion-targeting photosensitizer and given to tumor cells, induced the synergistic anti-tumor effect by combing photodynamic and immunotherapy 80. The in vitro and in vivo results reveal that the nanosystem not only efficiently induced an immune response by photodynamic therapy, but also subsequently induced a siRNA-mediated immune checkpoint blockade that further activated systemic anti-tumor immune responses, and thereby led to significant growth inhibition for melanoma. A similar result has also been reported by Qiao et al. They designed a ROS-responsive nanotheranostic system which combined temozolomide (TMZ)-mediated chemotherapy and immunomodulation by siTGF-β-based therapy on glioblastoma 84. In this study, cationic poly[(2-acryloyl)ethyl(p-boronic acid benzyl)diethyl ammonium bromide] (BA-PDEAEA, BAP) was used to condense with TGF-β siRNA, the zwitterionic lipid-based envelopes (ZLEs) were then coated on polymer-siRNA nanocomplex, and TMZ was loaded into the core of the nanotheranostic NPs (LiB(T+AN@siTGF-β), LBTA). The NPs were finally modified with an angiopep-2 peptide that enabled the NPs to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and accumulate into the glioblastoma tumor region. Both in vitro and in vivo results demonstrated that this nanotheranostic NPs effectively down-regulated TGF-β expression of tumor cells and dramatically enhanced the efficacy of TMZ mediated chemotherapy. Meanwhile, it showed that the survival time of glioblastoma tumor-bearing mice was significantly prolonged after the synergistic combination treatment.

In addition to directly silencing the immunosuppressive genes, combination therapy with knock out/down oncogenic genes, through siRNA and immune checkpoint blockade therapy, may provide another promising method for cancer treatment. For example, Matsuda et al. used the extracellular vesicles (EVs) to develop a biological nanoparticle-mediated delivery system for intrahepatic delivery of β-catenin siRNA to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)88. In this study, the β-catenin siRNA EVs and anti-PD-1-based therapy were systemically administrated together. The in vivo results demonstrated the therapeutic EVs improved CD8+ T cells infiltration and priming, and thus enhanced the anti-tumor effect of anti-PD-1.

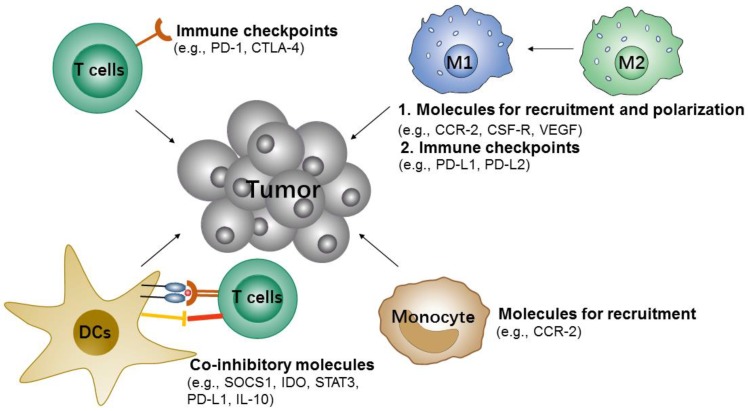

3.1.2 Immune cells-targeted siRNA immune-nanotherapy

During tumor progression, the immune cells can also recognize and eliminate tumor cells, which are known as tumor immunosurveillance. However, tumor cells can also change the host's immune system and escape immune system control by re-education or re-programing the immune cells, e.g., recruitment of various immunosuppressive cells to the primary microenvironment of the tumor, induction of immune cells into pro-tumorigenic types and inhibition of the anti-tumor activity of immune cells 109-111. Therefore, suppressing the immunosuppressive cells or modulating immune cells to anti-tumorigenic types would be an attractive approach to inhibit tumor immune escape and slow tumor growth (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Potential siRNA targets of immune cells for cancer immunotherapy.

3.1.2.1 T cells

Like cancer cells' highly/over-expressed inhibitory molecules (e.g., PD-L1), some activated T cells also over-express corresponding inhibitory molecules 112, 113, such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and mucin-containing protein 3 (TIM-3). All these inhibitory signals are known as immune checkpoints, which can downregulate, T cell activities and therefore prevent the elimination of tumor cells by effector T cells 113. Thus, targeting the immune checkpoints of T cells may also boost the anti-tumor effects. Given this, Li et al. constructed cationic lipid-assisted PEG-PLA-based NPs for efficiently delivering CTLA-4 siRNA to T cells 90. The NPs consisted of poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(d,l-lactide) (PEG5k-PLA11k) and the cationic lipid N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-N-methyl-N-(2-cholesteryoxycarbonyl-aminoethyl) ammonium bromide (BHEM-Chol) polymers which could encapsulate with CTLA-4 siRNA by electrostatic interaction. Although the NPs were only internalized by 4-6% of T cells in vivo, it promoted an ~ 2-fold increase in effector CD8+ T cells (approximately 40.3% vs. 18.9% of PBS), and the ratio of CD4+ FOXP3+ Tregs was decreased by ~ 2.5 fold compared to PBS. Accordingly, these NPs could effectively inhibit tumor growth and prolong survival time in mice with melanoma.

3.1.2.2 TAMs

Macrophages are professional phagocytes for eliminating pathogens and cellular debris. In the tumor microenvironment, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) usually are either pro-tumor M2 type or anti-tumor M1 type. The macrophages or monocytes are usually recruited to the tumor region and polarized to M1-type at the initial stages of tumor formation, and in advanced tumor progression stage, the macrophages will convert from M1 to M2 type, which thus exerts pro-tumor effects by helping block CD8 T cells 114, 115. Conclusively, reducing the survival and recruitment of TAMs in tumor site or performing targeted delivery of therapeutics to the M2-like TAMs, for depleting them from tumors or converting them to M1 type, would be promising strategies for cancer immunotherapy 116.

Recent studies indicated that the CCL2-CCR2 117 and CCL3-CCR1/CCR5 signaling 118 were required for the recruitment, retention, and the phenotypic recruitment of TAMs. They also indicated that the cytokines 119, including colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), are known to recruit monocytes as well. Given this, Qian et al. reported a molecularly-targeted strategy based on dual-targeting nanoparticles (M2NPs) that deliver colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) siRNA to M2-like TAMs for the specific blockade of the survival of M2-like TAMs, which results in the depletion of them from melanoma tumors 93. The siRNA-carrying M2NPs can inhibit the production of immunosuppressive factors (e.g., IL-10 and TGF-β), but also increase the expression of immunostimulatory cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-12) and CD8+ T cells infiltration (2.9-fold). Moreover, it effectively induced the anti-tumor activity of T cells by down-regulating expressions of the exhaustion markers (PD-1 and Tim-3) and stimulating secretion of IFN-γ (6.2-fold). In vivo results confirmed that M2NPs led to a dramatic elimination of M2-like TAMs (52%), inhibition of tumor growth (87%), and prolonged survival.

Conde et al. presented peptide-functionalized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) for delivery of VEGF siRNA to M2-like TAMs where a decrease in the accumulation in lung tumor tissue was observed, alongside enhanced tumor growth inhibition in a lung cancer orthotopic murine model 92. VEGF is a key angiogenic factor, which is highly expressed on M2-like TAMs and well known to promote cancer progression and metastasis. In this study, the authors proved that siRNA mediated gene silencing for inhibiting TAMs accumulation could be achieved by targeting the VEGF pathway, which also indicated that modulation for TAMs would induce an anti-tumor immune response and could be a potential target for cancer treatment.

3.1.2.3 DCs

DCs are the most important antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which could capture, process, and present tumor antigens to either naive CD8+ or CD4+ T cells. The functions of DCs are either mediating immune tolerance or inducing an anti-tumor immune response. Generally, DCs express a variety of co-inhibitory molecules 120, such as suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) 1, signal transducers and activators of transcription-3 (STAT3), and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). All of these molecules may suppress the antigen presentation process of DCs. Studies have shown that knockdown of these molecules by RNAi would be an effective strategy for DCs-based immunotherapy 121-124. Based on this, Heo et al. reported a PLGA polymeric NPs that combined the delivery of tumor antigens and SOCS1 siRNA to DCs that induced an enhanced anti-tumor immune response 102. SOCS1 functions as a broadly immuno-suppressive protein which can directly inhibit antigen presentation of DCs to T cells, and it also acts as a negative regulator of Janus kinases (JAKs), which induce immune tolerance. In this study, PLGA polymeric NPs with the loading of SOCS1 siRNA and OVA peptide were efficiently taken up by bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) and this showed proof of the significant knockdown effect on the expression of SOCS1. The downregulation of SOCS1 in BMDC further led to a drastic enhancement in cytokine production, and finally resulted in the essential induction of anti-tumor immune response.

3.1.2.4 Others

Neutrophils has been described as part of the innate immune response, but recent studies have shown that neutrophils can be a key negative regulator for adaptive immune responses by suppressing T cell proliferation, and therefore they also be so-called myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)125. MDSCs have been identified to facilitate the development of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment 126. Many studies have also demonstrated MDSCs are critically involved in immunosuppressive effects through the high expression of metabolic enzymes 127, 128, such as IDO, and arginase-1 (ARG1), cytokines129, 130, and chemokines, such as TGF-β and IL-10. Meanwhile, the recruitment of MDSCs relies on the chemokines 131 (e.g., CCL2). Due to the important role in tumor-associated immune suppression of MDSC, many studies were focused on exploring therapeutic strategies to eliminate these cells or to modulate their functions 132-135. For example, Leuschner et al. introduced monocyte-targeting lipid NPs for the delivery of CCR2 siRNA to the inflammatory monocyte 104. The results showed efficient inhibition of CCR2 expression by siRNA-mediated CCR2 gene silencing in monocytes that prohibited their accumulation in inflammatory sites and reduced the number of TAMs.

3.2 Nanostructure-mediated microRNA delivery for immunotherapy

Non-coding RNAs are usually classified into small non-coding RNA (e.g., microRNA) and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA, > 200 nt), depending on their size. Recent studies of lncRNAs have indicated that lncRNAs function as crucial regulators in various immunity processes, including immune cells differentiation and function, regulation for tumor microenvironment, but the detail regulatory mechanisms remain unclear 136. While current studies are mainly focused on the development of the lncRNAs for immune regulation and the functional relationship between lncRNAs and immunity, and there were limited reports on lncRNAs-based nanomaterials for immunotherapy, we might believe that lncRNAs could become a novel therapeutic agent in cancer immunotherapy.

In addition, recently studies have shown that microRNAs are associated with the modulation of various pathways of cancer and immune cells. MicroRNAs usually produce competition for oncogenic and tumor suppressive effects by blocking either tumor suppressive mRNA or oncogenic mRNA 137-139. Generally, oncogenic microRNAs are highly/over-expressed in cancer cells, while tumor-suppressive microRNAs are under-expressed. Restoration of tumor-suppressive microRNAs could both inhibit cancer cell proliferation and induce cell apoptosis. Because of these possibilities, this technique has been viewed as novel therapeutics for cancer treatment 6, 140. Ultimately, it is necessary to carefully assess the specific roles of microRNAs in cancer or immune cells, and develop an effective and safe microRNA-based therapeutic for cancer treatment.

3.2.1 Tumor cells-targeted microRNA immunonanotherapy

As mentioned above, tumor cells will up-regulate the expression of immune checkpoint proteins, or “don't eat me” signals, to construct an immunosuppressive microenvironment. microRNA acts as a gene regulator, which can either be used to directly inhibit expressions of immune escape factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines or act as oncogenic factors for facilitating immune system evasion by tumor cells141. For example, many microRNAs including miR-34a, miR-200, miR-142-5p and miR-424, et al. have been found to be involved in PD-L1 expression levels in several cancer cells 142, 143. Among them, miR-424 not only activates T cells immune response through direct targeting of PD-L1, but also can restore the chemosensitivity of ovarian cancer cells 144. However, some microRNAs, such as miR-20b, miR21, and miR-130b, have been found to inhibit PTEN expression in colorectal cancer, but they in turn promote PD-L1 upregulation 145. MicroRNA antagonists are short, single-stranded oligonucleotide molecules complementary to microRNA sequences that have recently been used for targeting and reducing microRNA activity. Therefore, using antagonists of microRNA will also decrease oncogenic microRNA activity and provide promising results of targeted genes for immunomodulation. To date, there has been a limited report by using nanotechnology for the delivery of microRNA to tumor cells for triggering an anti-tumor immune response, but there is high confidence that it would be a potential strategy for cancer immunotherapy.

3.2.2 Immune cells-targeted microRNA immunonanotherapy

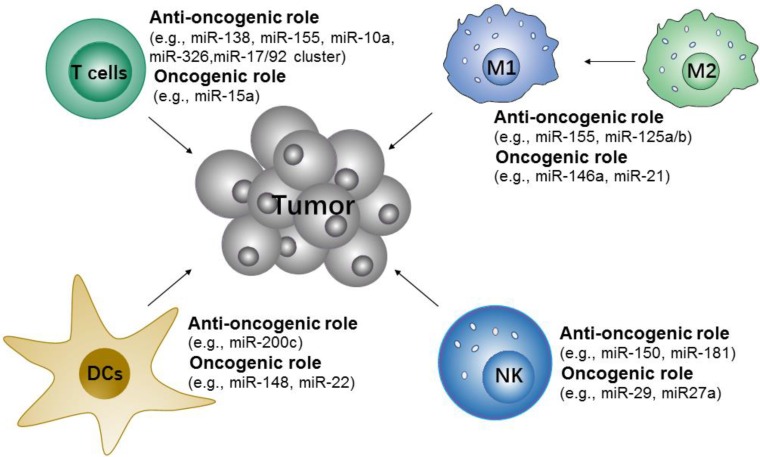

Many studies have shown that microRNAs are important in the modulation of innate and adaptive immune-responses via controlling the differentiation and activation of immune cells and the maintenance of immune proinflammation factors 141. These microRNAs either contribute to or repress the immune cells to initiate anti-tumor responses (Figure 5). Specifically, the upregulation of miR-146a 146 and miR-21147 attenuate M1-like TAMs activation by targeting TLR/NF-κB pathway, but miR-155148, 149 promote M1-like TAMs polarization by targeting SOCS1 or targeting the negative regulator of NF-κB and TNF-α-induced protein 3. Along with TAMs, some microRNAs, such as miR-150 and miR-181a/b, have been found to control the differentiation of NK cells 150. The use of miR-148 and miR-22 inhibitors may also promote DCs maturation 151-153. In addition, the differentiation and functions of different T cell subsets are regulated by microRNAs 154, 155. For example, miR-155 are more in favor of Th1 phenotype 156, miR-326 promote Th17 differentiation 157, and miR-10a and miR-17/92 cluster regulate T follicular helper maturation 158.

Figure 5.

Potential microRNA targets of immune cells for cancer immunotherapy. The microRNAs either contribute to or repress the immune cells to initiate anti-tumor responses.

Given the potential applications of microRNA-based therapeutics in cancer immunotherapy, a variety of microRNA-based nanomaterials that can efficiently target immune cells for immunomodulation have been developed (Table 3). For instance, Zhang et al. designed lipid-coated calcium phosphonate nanoparticles (CaP/miR@MNPs) which were further conjugated with mannose for specific delivery of miR155 to TAMs 159. The results demonstrated that CaP/miR@MNPs could successfully transfer pro-tumor M2-like TAMs to antitumor M1-like TAMs, and therefore elicit a potent antitumor immune response, whilst inhibiting tumor growth. Similarly, Parayath et al. developed a CD44 targeting hyaluronic acid-poly(ethylenimine) (HA-PEI)-based nanoparticle for the delivery of miR-125b to peritoneal macrophages 160. Overexpression of miR-125b in macrophages would promote M1-like TAMs activation and lead to inhibition of primary tumor growth and metastasis. In vivo results showed that there was a more than 6-fold increase in the ratio of M1 to M2 TAMs and 300-fold increase in the ratio of iNOS (M1 marker) to Arg-1 (M2 marker) in TAMs after treatment with HA-PEI-125b nanoparticles. All of the examples above indicated that successfully inducing M1-like TAMs polarization would enhance anti-cancer immunotherapy.

Table 3.

Summary of microRNA-based nanotherapeutics for cancer immunotherapy

| Cells | Nanocarriers | microRNA | Immunological effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T cells | Exosome-like nanovesicles | miR-150 Antagonist | T-cell regulation | 160 |

| TAMs | Layered double hydroxides NPs | miR-155 | Repolarize M2 to M1 | 161 |

| Lipid-coated NPs | miR-155 | Repolarize M2 to M1 | 158 | |

| CD44 coated HA-PEI based NPs | micR-125b | Reprogram TAMs into M1 | 159 | |

| DCs | Exosomes | miR-155 | Increase the expressions of MHC-II, CD86, CD40, and CD83, and promote the secretion of the IL12p70, IFN-gamma, and IL-10 | 162 |

| PEG-PLL-PLLeu polymeric NPs | miR-148a Antagonist | Reprogram DCs, reduce Treg cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells | 163 | |

| NK cells | Exosomes | miR-186 | Promote NK activation | 164 |

3.3 Nanostructure-mediated mRNA delivery for immunotherapy

mRNA emerging as a cancer therapeutic has drawn increasing attention due to its multiple unique features166, such as the absent risk of insertional mutagenesis, more consistent and predictable kinetics of protein expression, and relatively convenient in vitro synthesis. However, its poor stability (easily degraded by the nucleases) and propensity for immunostimulation have greatly hindered the in vivo application. Moreover, it very difficult for the larger mRNA molecules with negative charges to enter antigen-presenting cells (APCs) directly. Nanoparticle-based platforms with high cytosolic transportation and reduced renal filtration, could be emerging as a promising mRNA delivery tool to protect nucleic acids from enzymatic degradation and withstand multiple intracellular and extracellular barriers 35, 167. Here, we will describe two examples to present the advances of mRNA nanomedicines in immunotherapy applications, including vaccination and cell engineering.

3.3.1 mRNA-based NPs for vaccination

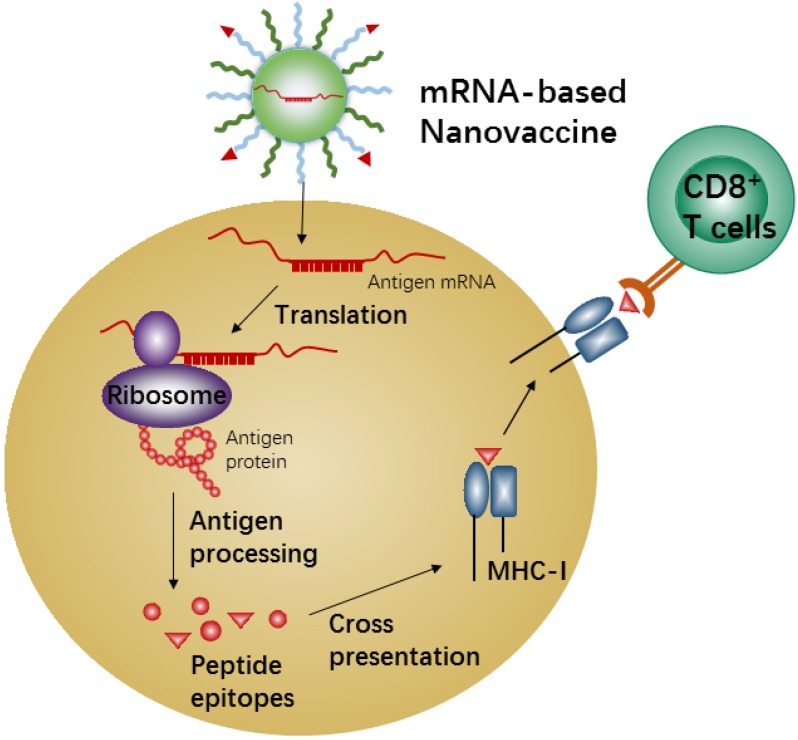

mRNA-based vaccines show a promising alternative due to the high potency, safe administration, and capacity for rapid development and low-cost manufacture168, 169. Recent nanotechnological advances have largely overcome the issues of in vivo mRNA delivery, and therefore mRNA-based nanovaccines have recently attracted increasing attention because of the promising results achieved in many anti-tumor vaccination studies in animal models 170, 171. Meanwhile, the mRNA-based vaccine could effectively carry out antigen-encoding mRNA to antigen presenting cells (APCs) in vivo directly. Also, the mRNA-based vaccine is unlimited in molecular structures and number of tumor antigen proteins. When the nanocarriers efficiently deliver these antigen-encoding mRNAs into APCs, the mRNAs will be released and translated into tumor antigenic proteins in the cytoplasm of APCs, which are then processed into peptide epitopes for subsequent binding with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I via cross-presentation pathway. The MHC-peptides are finally transferred to the cell surface of APCs for activation of CD8+ T cells, leading to corresponding anti-tumor immune responses (Figure 6). Efficient in vivo mRNA delivery and induction of strong cytotoxic T cell response are the key prerequisites for cancer immunotherapy by mRNA-based nanovaccines. There are so many advantages and disadvantages for in vivo application of mRNA-based nanovaccines, and many review articles have summarized the advertences of mRNA-based nanovaccines in cancer therapy. Here we just describe one example to present the mechanism of anti-tumor response by nanovaccine.

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of antigen cross-presentation by mRNA-based nanovaccine in APC.

A lipid nanovaccine with the loading of tumor-associated antigens mRNA (e.g., gp100 and TRP2) was designed by Oberli et al. 172. In this study, the lipid nanoparticle that consisted of an ionizable lipid, a lipid-PEG, a phospholipid, cholesterol, and an additive was developed. The ionizable lipid was used for complexation with the negatively charged mRNA and also helped with cellular uptake. The results showed the NPs worked well for the delivery of mRNA to dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, and effectively led to strong activation of CD8+ T cells after a single immunization in the B16F10 melanoma model. Moreover, after treatment with these NPs, B16F10 melanoma tumor experienced shrinkage, and mice survival was significantly extended. The exciting result from this study demonstrated that the induction of cytotoxic T cell response by mRNA nanovaccine would be an excellent candidate in the application of cancer treatment.

In the nanovaccine field, the nanostructures with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides that act as immuno-adjuvants for inducing immunostimulatory responses are very attractive. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides are Toll-like Receptor 9 (TLR9) agonists, which are expressed in human B and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Recent studies demonstrated CpG not only could induce apoptosis of tumor cells with high-expression of the TLR9 receptor, but also enhance NK cell activation and promote activation of anti-tumor immune response by combining with various of cytokine treatments 173, 174. Therefore, CpG-based nanotherapeutics can only benefit from combination with strategies of immune checkpoint blockade.

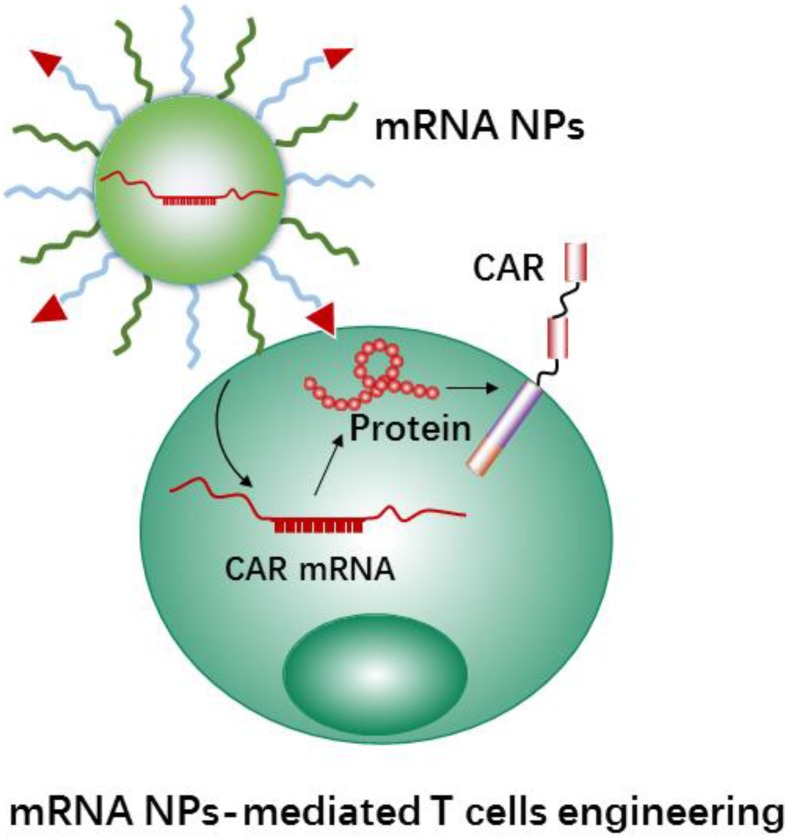

3.3.2 mRNA-based NPs for T cell engineering

As a novel immunotherapy method, CAR-T therapy has achieved great success in treating patients with hematological malignancies 13, such as leukemia and lymphoma therapy. Currently, the most common techniques for the development of CAR-engineered T cells are using viral gene transduction by virus-mediated delivery. However, using viral vectors may lead to the potential insertional mutagenesis and genotoxicity for effector T cells15. Meanwhile, the feared side-effects would happen when virus vectors transduced cells 175. Hence, more precise T cell manipulations are currently under investigation.

Using mRNA instead of DNA as T cell engineering therapeutics (Figure 7) is attractive due to the multiple unique features of mRNA 176, 177. Meanwhile, the use of nanocarriers protect mRNA therapeutics from degradation and may help with cellular uptake and endosomal escape. In addition, nanocarriers provide further advantages for the engineering of immune cells, e.g., coating with specific ligands for increasing cell binding and cellular uptake, and carrying multiple RNA payloads. Moffett et al. developed a targeted nanocarrier for reprogramming T cells by delivery of several mRNAs to T cells 178. The nanocarrier consisted of negatively charged polyglutamic acid (PGA), poly(β-amino ester) (PBAE) polymers and T cell targeting ligands (e.g., anti-CD3 and anti-CD8). In this study, the authors first used their nanocarrier to deliver FoxO1 (Forkhead box O1, a transcription factor to promote the generation and maintenance of memory T cells) mRNA to CAR T cells for overexpressing FoxO1. FoxO1 overexpression can bias CAR-T-cells toward a central memory phenotype and therefore improve the anti-tumor activity of CAR T cells. In addition, the authors developed mRNA nanocarriers to transiently express genome-editing proteins (CRISPR) for efficiently knocking out T cells receptors in CAR-programmed lymphocytes. The results demonstrated that the NPs could effectively transport mRNAs to targeted T cells, and subsequently led to the targeted T cells to express selected proteins. Next, we will describe CRISPR-Cas9 nanotechnology mediated cell engineering and its application in immunotherapy.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of mRNA nanotherapeutics for T cell engineering. The nanocarriers delivery CAR mRNA to T cells, and induce T cells activation by expressing the CAR protein on the surface of T cells.

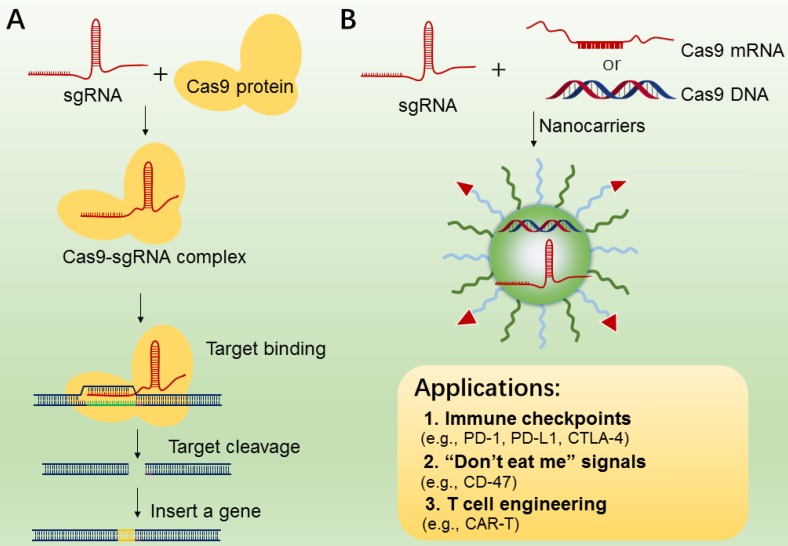

3.4 CRISPR-Cas9 nanotechnology for cell engineering

CRISPR/Cas9 system (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) 178, is an RNA-guided DNA targeting technology, which has been widely applied to genome editing 180, 181, gene therapy 182 and manipulation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) studies183. The CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing machinery is comprised of two essential components, i.e., sgRNA and DNA endonuclease Cas9 (Figure 8A). The Cas9 protein functions in locating and cleaving targeted DNA, and the guide RNA has a 5′ end that is complementary to the target DNA sequence. Only when two macromolecules are forming a complex, will the cleavage activity of Cas 9 begin to be triggered (Figure 8A). In cancer immunotherapy, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing is usually applied to knockout the genes that encode inhibitory receptor proteins of tumor or T cells, such as PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4184-186. In 2016, a case of CRISPR-Cas9 application in a clinical trial of T cells engineering by deleting PD-1 was performed in China, and the result was promising187, indicating the potential value of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing in immunotherapy.

Figure 8.

A. The mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 technology for gene editing. B. CRISPR-Cas 9 nanotherapeutics for cell engineering and the applications in cancer immunotherapy. The CRISPR-Cas 9 system (sgRNA with Cas9 mRNA or DNA or protein) was transported to tumor or immune cells by nanocarriers.

While CRISPR-Cas9 has been used as a particularly versatile and operationally simple tool for gene editing in many cell types, the effective delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 system into targeted T cells is still the common issue for efficient genome editing. In addition, off-target effects are also found in many CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene-editing studies 188. To reduce these effects, various nanocarriers have been developed as the delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 system189-191, which may be applied to manipulations of immune cells (TAMs, B cells, and T cells) and tumor cells (Figure 8B). In addition, compared to the viral vectors with high immunogenicity, various types of lipid-based or polymer-based nanocarriers, which are actively targetable with low immunogenicity, showed exciting delivery efficiency192, 193. For example, Ray et al reported a nanomaterial platform based cationic arginine-coated gold nanoparticles194, which delivered CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing machinery into macrophage cells for knockout expression of “don't eat me” signals (SIRP-α). The NPs based nanoplatform has shown ∼90% delivery efficiency as well as ∼30% gene editing efficiency. The in vitro experimental results also showed a 4-fold increase in the innate phagocytic capabilities of the macrophages by using this strategy to turn off the “don't eat me” signal on macrophages, indicating this strategy may be a promising tool for the development of “weaponized” TAMs for cancer immunotherapy. Similarly, Cheng et al. proposed a double emulsion method by complexing plasmids with stearyl polyethyleneimine (stPEI) as the core to form human serum albumin (HSA) (plasmid/stPEI/HSA) NPs for delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 195. The NPs could disrupt or silence the expression of PD-L1 by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing.

4. Conclusions and future perspectives

During the past few years, immunotherapy has shown to be one of the most promising therapeutic strategies and has resulted in a paradigm shift in the treatment of cancers 13, 112. RNA-based therapeutics provide several advantages in immunomodulation and cancer vaccines, which will serve as a competitor and as a current immunotherapies partnership to achieve synergistic combinations for more efficient and personalized results 75, 169, 176, 196. Compared to the conventional proteins, antibodies, and cell-based therapeutics (e.g., CAR-T), RNA-based therapeutics including siRNA, microRNA, and mRNA can either knock out or knock down targeted genes or upregulate expressions of specific proteins, and such features of RNA-based therapeutics cause high selectivity and low risk of off-target hitting. Meanwhile, RNA-based therapeutics have become much more diverse and broad in regulatory functions in immunotherapy than the other antibody or protein-based therapies. For example, RNA-based therapeutics could activate rapid and effective anti-cancer immune response by inducing immunogenic cell death of tumor cells, and thus may skip the requirement of deep tumor penetration-a significant hurdle faced by traditional cancer nanomedicines. Moreover, the development and production of RNA therapeutics are very convenient, rapid and cost-effective 197. The success of pre-clinical studies has led to the initiation of clinical trials of different forms of RNA therapeutics for cancer immunotherapy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Current clinical studies of RNA-mediated immunotherapy for the treatment of cancer

| Targeting Cell | RNAs Encoding | Cancer Types | Status | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T cells | MET scFv CAR | Malignant Melanoma, Breast Cancer | Early Phase 1 Recruiting | NCT03060356 |

| cMet CAR | Metastatic Breast Cancer; Triple Negative Breast Cancer | Phase 1 Completed | NCT01837602 | |

| Chimeric anti-mesothelin immunoreceptor SS1 | Pancreatic Cancer | Phase 1 Completed | NCT01897415 | |

| DCs | TAAs: NY-ESO-1, MAGEC1, MAGEC2, 5 T4, Survivin, and MUC1 | Lung Cancer | Phase 2 Recruiting | NCT03164772 |

| TAAs: PSA, PSCA, PSMA, STEAP1, PAP and MUC1 | Prostate Carcinoma | Phase 2 Completed | NCT02140138 | |

| Neo-Ag | Melanoma | Active No Recruiting |

NCT02035956 | |

| Neo-Ag | Solid tumor | Phase 1 Recruiting | NCT03313778 | |

| Neo-Ag | Melanoma; Colon Cancer; Gastrointestinal Cancer; Genitourinary Cancer; Hepatocellular Cancer | Phase 2 Completed | NCT03480152 | |

| Three variant RNAs; p53, and Neo-Ag based on NGS screening | Breast Cancer (Triple Negative Breast Cancer) | Phase 1 Recruiting | NCT02316457 | |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen RNA | Colorectal Cancer; Metastatic Cancer | Phase 2 Completed | NCT00003433 | |

| Prostate specific antigen (PSA) | Prostate Cancer | Phase 2 Completed | NCT00004211 | |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | Breast Cancer; Colorectal Cancer; Extrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer | Phase 1 Completed | NCT00004604 | |

| Total tumor RNA | Kidney Cancer | Phase 1 Completed | NCT00005816 | |

| Autologous tumor RNA | Melanoma | Phase 3 Recruiting | NCT01983748 | |

| TAAs: NYESO-1, MAGE-A3, tyrosinase, and TPTE | Melanoma | Phase 1 Recruiting | NCT02410733 | |

| siRNA: LMP2, LMP7, and MECL1; mRNA: MART-1, tyrosinase, gp100, and MAGE-3 | Melanoma | Phase 1 Completed | NCT00672542 | |

| Melan-A, Mage-A1, Mage-A3, Survivin, GP100 and Tyrosinase | Malignant Melanoma | Phase 1/2 Completed | NCT00204516 | |

| pp65-flLAMP | Glioblastoma | Active No recruiting | NCT03615404 |

Given the potentials of these RNA therapeutics, various nanoparticle-based delivery systems, such as lipid-based, polymeric, inorganic and bio-inspired nanomaterials have been explored extensively 49, 167, 198, 199. These nanoparticle-based delivery systems not only carry a high dose of therapeutic payloads to targeted cells or tissues, but also show the same regulatory functions in immunotherapy with RNA therapeutics. In addition, the combination of RNA-mediated nano-immunotherapy with chem- or photodynamic therapies demonstrated promising results in an animal model81, 106. Meanwhile, combining RNA-mediated nanotherapy with current immunotherapies (e.g., anti-CTLA-4, anti-PD-1, and anti-PD-L1) is also a great opportunity to enhance cancer treatments 133. However, there are still several issues need to be solved before such applications are translated to the clinic.

To begin with, some of the main barriers that hinder the stability and in vivo safety of the various nanomaterial carriers include cytotoxicity and undesirable immune stimulation 21, 200. As mentioned previously, potential in vivo toxicity issues can arise from the use of cationic units in polymeric NPs, payload leakages from lipid-based nanostructures, and the non-biodegradability of inorganic NPs 20, 38. In addition, the NPs may be recognized as a foreign substance, and thus easily excreted by renal/hepatic clearance or eliminated by the innate immune systems 198. To address these issues, nanocarriers should be bio-compatible and capable of biodegradability by modulating the surface of the NPs with biomolecules or proper hydrophilic materials such as PEG.

Secondly, nanocarriers must increase cell targeting and cell internalization. For example, for targeting tumor cells to silence PD-L1 by RNA-based NPs, it needs to target as many of them as possible, thus requiring high accumulation and deep tumor penetration. To increase cellular uptake and thus increase the effectiveness of RNA delivery, NPs could be coated with targeting ligands, which would increase the chance of binding to the targeted cells. In addition, effective on-demand RNA delivery and release would become feasible through the incorporation of backbones of that are sensitive to different stimuli, either endogenous (e.g., pH, enzyme, and redox) or exogenous (e.g., temperature, electricity, light, magnetic force, ultrasound)201, 202. Such a feature of nanocarriers would enable optimal spatial and temporal release of RNA payloads. Despite many nanovesicles infiltrating the targeted cells through the endocytic pathway, they must still overcome the barriers that endosomes and lysosomes pose before achieving the ultimate goal of cytosolic release of RNA therapeutics 203. Generally, nanomaterials are transported into the endosome, which then fuses with lysosomes and ultimately destroys the RNA cargoes. Some specific targeting peptides (e.g., HA) or surfactants can be used in the preparation of nanocarriers to enable the endosomal/lysosomal escape via the proton sponge effect or membrane lysis. It should be noted that many stimuli-responsive nanomaterials had potential dose-dependent cytotoxicity. This cytotoxicity was due to the stimuli-responsive motif often being limited by insufficient biocompatibility or the need for bio-degradability 204. Meanwhile, the complexity of the architectural design and difficulties in the synthesis of these NPs are likely to hamper their clinical translation. Therefore, the benefit-to-risk ratio for the development of responsive NPs needs to be balanced, and the issues related to the responsive characteristics would eventually need to be solved.

In summary, the goal of the current review article was to summarize and highlight the RNA-based nanotherapeutics for the immunomodulation and enhancement of cancer immunotherapy. Given the convenience and importance of RNA therapeutics in cancer immunotherapy, using nanomaterials for effectively delivery of RNA to a targeted tumor or immune cells for triggering anti-tumor immune response have already produced some exciting results in the treatment of cancer. Meanwhile, by combining RNA-mediated immunomodulation with ICB immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and photodynamic therapy, synthesized effects have been noted and a bright future for the clinical use of cancer treatment awaits. Although the RNA delivery nanoplatforms for clinical applications is still challenging, some issues need to be solved before this nanotherapeutics translated from the bench to the bedside. We believe that the RNA-mediated nano-immunotherapy has great potential to overcome some of these shortcomings and has the opportunity to be used for cancer treatment in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award and CA200900 (J.S.). Y.-X. Lin thanks the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M633260, 2018T110918) and Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2018A030310098) for financial support, and S. Blake thanks the Tufts Center for Stem Diversity and the Harvard Yes for Cure Program.

Abbreviations

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- ICB

immune checkpoint blockade

- CAR-T

chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- AGO2

Argonaute-2

- pri-microRNA

primary microRNA

- pre-microRNA

precursor microRNA

- UTR

untranslated region

- ORF

open reading frame

- NPs

nanoparticles

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention effect

- PLGA

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PVA

polyvinyl alcohol

- PLA

poly-l-lactic acid

- MSNs

mesoporous silica nanoparticles

- CNTs

carbon nanotubes

- QDs

quantum dots

- PCL-PEG

polycaprolactone-polyethyleneglycol

- PCL-PEI

polycaprolactone-polyethylenimine

- FA-PEI

folic acid- polyethylenimine

- PDPA

poly(2-(diisopropylamino)ethyl methacrylate

- PEG-PLL-PLLeu

poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lysine)-b-poly(l-leucine)

- PEG /MT/PC NPs

polyethylene glycol (PEG)/mannose doubly modified trimethyl chitosan ( MT)/poly (allylamine hydrochloride) (PC)-based nanoparticles (NPs)

- HA

hyaluronic acid

- AuNPs

gold nanoparticles

- OVA

Ovalbumin

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma cells

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- CXCL5

C-X-C motif chemokine 5

- PD-1

programmed death receptor-1

- PD-L1

programmed death receptor-1 ligand

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- TIM-3

mucin-containing protein 3

- CSF1

colony stimulating factor 1

- CSF-1R

colony stimulating factor-1 receptor

- IFN-γ

interferon γ

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- Th cells

T helper cells

- DCs

dendritic cells

- TAMs

Tumor-Associated Macrophages

- NK

natural killer cells

- MDSCs

myeloid derived suppressor cells

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- SOCS1

suppressor of cytokine signaling 1

- IDO

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription-3

- ARG1

arginase-1

- TLR

Toll-like receptors

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- FoxO1

Forkhead box O1

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

References

- 1.Adams BD, Parsons C, Walker L, Zhang WC, Slack FJ. Targeting noncoding RNAs in disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:761–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI84424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakraborty C, Sharma AR, Sharma G, Doss CGP, Lee SS. Therapeutic miRNA and siRNA: moving from bench to clinic as next generation medicine. Mol The Nucleic Acids. 2017;8:132–43. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaczmarek JC, Kowalski PS, Anderson DG. Advances in the delivery of RNA therapeutics: from concept to clinical reality. Genome Med. 2017;9:60. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0450-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:203–21. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao BXS, Roundtree IA, He C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:31–42. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirzaei H, Masoudifar A, Sahebkar A, Zare N, Nahand JS, Rashidi B. et al. MicroRNA: a novel target of curcumin in cancer therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:3004–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenblum D, Joshi N, Tao W, Karp JM, Peer D. Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1410. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03705-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou ZX, Liu XR, Zhu DC, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Zhou XF. et al. Nonviral cancer gene therapy: delivery cascade and vector nanoproperty integration. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;115:115–54. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyer AK, Duan ZF, Amiji MM. Nanodelivery systems for nucleic acid therapeutics in drug resistant tumors. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:2511–26. doi: 10.1021/mp500024p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen BL, Dai WB, He B, Zhang H, Wang XQ, Wang YG. et al. Current multistage drug delivery systems based on the tumor microenvironment. Theranostics. 2017;7:538–58. doi: 10.7150/thno.16684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajj KA, Whitehead KA. Tools for translation: non-viral materials for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater. 2017;2:17056. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.June CH, O'Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, Milone MC. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2018;359:1361–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalil DN, Smith EL, Brentjens RJ, Wolchok JD. The future of cancer treatment: immunomodulation, CARs and combination immunotherapy. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2016;13:273–90. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonifant CL, Jackson HJ, Brentjens RJ, Curran KJ. Toxicity and management in CAR T-cell therapy. Mol The Oncolytics. 2016;3:16011. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, Wierda W, Gutierrez C, Locke FL. et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy-assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2018;15:47–62. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R. et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aagaard L, Rossi JJ. RNAi therapeutics: principles, prospects and challenges. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li ZH, Rana TM. Therapeutic targeting of microRNAs: current status and future challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:622–38. doi: 10.1038/nrd4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo X, Huang L. Recent advances in nonviral vectors for gene delivery. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:971–9. doi: 10.1021/ar200151m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samal SK, Dash M, Van Vlierberghe S, Kaplan DL, Chiellini E, Van Blitterswijk C. et al. Cationic polymers and their therapeutic potential. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:7147–94. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35094g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang SB, Zhao B, Jiang HM, Wang B, Ma BC. Cationic lipids and polymers mediated vectors for delivery of siRNA. J Control Release. 2007;123:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin YX, Gao YJ, Wang Y, Qiao ZY, Fan G, Qiao SL. et al. pH-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles with gold(I) compound payloads synergistically induce cancer cell death through modulation of autophagy. Mol Pharm. 2015;12:2869–78. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin YX, Wang Y, Qiao SL, An HW, Zhang RX, Qiao ZY. et al. pH-sensitive polymeric nanoparticles modulate autophagic effect via lysosome impairment. Small. 2016;12:2921–31. doi: 10.1002/smll.201503709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Lin YX, Qiao ZY, An HW, Qiao SL, Wang L. et al. Self-assembled autophagy-inducing polymeric nanoparticles for breast cancer interference in-vivo. Adv Mater. 2015;27:2627–34. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loh XJ, Lee TC, Dou QQ, Deen GR. Utilising inorganic nanocarriers for gene delivery. Biomater Sci. 2016;4:70–86. doi: 10.1039/c5bm00277j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen JL, Zhang W, Qi RG, Mao ZW, Shen HF. Engineering functional inorganic-organic hybrid systems: advances in siRNA therapeutics. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47:1969–95. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00479f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elbashir SM, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. RNA interference is mediated by 21-and 22-nucleotide RNAs. Genes Dev. 2001;15:188–200. doi: 10.1101/gad.862301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan L, Sun X. Recent advances in mRNA vaccine delivery. Nano Res. 2018;11:5338–54. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundqvist A, Noffz G, Pavlenko M, Saeboe-Larssen S, Fong T, Maitland N. et al. Nonviral and viral gene transfer into different subsets of human dendritic cells yield comparable efficiency of transfection. J Immunother. 2002;25:445–54. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Tendeloo VFI, Ponsaerts P, Lardon F, Nijs G, Lenjou M, Van Broeckhoven C. et al. Highly efficient gene delivery by mRNA electroporation in human hematopoietic cells: superiority to lipofection and passive pulsing of mRNA and to electroporation of plasmid cDNA for tumor antigen loading of dendritic cells. Blood. 2001;98:49–56. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsui A, Uchida S, Ishii T, Itaka K, Kataoka K. Messenger RNA-based therapeutics for the treatment of apoptosis-associated diseases. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15810. doi: 10.1038/srep15810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiong QQ, Lee GY, Ding JX, Li WL, Shi JJ. Biomedical applications of mRNA nanomedicine. Nano Res. 2018;11:5281–309. doi: 10.1007/s12274-018-2146-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pecot CV, Calin GA, Coleman RL, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK. RNA interference in the clinic: challenges and future directions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery. Nat Mater. 2013;12:991–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomes-da-Silva LC, Fonseca NA, Moura V, de Lima MCP, Simoes S, Moreira JN. Lipid-based nanoparticles for siRNA delivery in cancer therapy: paradigms and challenges. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:1163–71. doi: 10.1021/ar300048p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li WJ, Szoka FC. Lipid-based nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery. Pharm Res. 2007;24:438–49. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tseng YC, Mozumdar S, Huang L. Lipid-based systemic delivery of siRNA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:721–31. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jayaraman M, Ansell SM, Mui BL, Tam YK, Chen J, Du X. et al. Maximizing the potency of siRNA lipid nanoparticles for hepatic gene silencing in vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:8529–33. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato Y, Hashiba K, Sasaki K, Maeki M, Tokeshi M, Harashima H. Understanding structure-activity relationships of pH-sensitive cationic lipids facilitates the rational identification of promising lipid nanoparticles for delivering siRNAs in vivo. J Control Release. 2019;295:140–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shim MS, Kwon YJ. Stimuli-responsive polymers and nanomaterials for gene delivery and imaging applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1046–58. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanner P, Baumann P, Enea R, Onaca O, Palivan C, Meier W. Polymeric vesicles: from drug carriers to nanoreactors and artificial organelles. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1039–49. doi: 10.1021/ar200036k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dahlman JE, Barnes C, Khan OF, Thiriot A, Jhunjunwala S, Shaw TE. et al. In vivo endothelial siRNA delivery using polymeric nanoparticles with low molecular weight. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:648–55. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar A, Kumar V. Biotemplated inorganic nanostructures: supramolecular directed nanosystems of semiconductor(s)/metal(s) mediated by nucleic acids and their properties. Chem Rev. 2014;114:7044–78. doi: 10.1021/cr4007285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin G, Mi P, Chu CC, Zhang J, Liu G. Inorganic nanocarriers overcoming multidrug resistance for cancer theranostics. Adv Sci. 2016;3:1600134. doi: 10.1002/advs.201600134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoo JW, Irvine DJ, Discher DE, Mitragotri S. Bio-inspired, bioengineered and biomimetic drug delivery carriers. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:521–35. doi: 10.1038/nrd3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X, Liang QM, Zhang W, Li YL, Ye JD, Zhao FJ. et al. Bio-inspired bioactive glasses for efficient microRNA and drug delivery. J Mater Chem B. 2017;5:6376–84. doi: 10.1039/c7tb01021d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abd E, Khalil IA, Elewa YHA, Kusumoto K, Sato Y, Shobaki N. et al. Lung-endothelium-targeted nanoparticles based on a pH-sensitive lipid and the gala peptide enable robust gene silencing and the regression of metastatic lung cancer. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29:1807677. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singha K, Namgung R, Kim WJ. Polymers in small-interfering RNA delivery. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2011;21:133–47. doi: 10.1089/nat.2011.0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Usman A, Zia KM, Zuber M, Tabasum S, Rehman S, Zia F. Chitin and chitosan based polyurethanes: a review of recent advances and prospective biomedical applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;86:630–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mano JF, Silva GA, Azevedo HS, Malafaya PB, Sousa RA, Silva SS. et al. Natural origin biodegradable systems in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: present status and some moving trends. J Royal Soc Interface. 2007;4:999–1030. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2007.0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houacine C, Yousaf SS, Khan I, Khurana RK, Singh KK. Potential of natural biomaterials in nano-scale drug delivery. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24:5188–206. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190118153057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Islam MA, Xu YJ, Tao W, Ubellacker JM, Lim M, Aum D. et al. Restoration of tumour-growth suppression in vivo via systemic nanoparticle-mediated delivery of PTEN mRNA. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2:850–64. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0284-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu YL, Ji XY, Tong WWL, Askhatova D, Yang TY, Cheng HW. et al. Engineering multifunctional RNAi nanomedicine to concurrently target cancer hallmarks for combinatorial therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2018;57:1510–3. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shi JJ, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:20–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu XD, Wu J, Liu SS, Saw PE, Tao W, Li YJ. et al. Redox-responsive nanoparticle-mediated systemic RNAi for effective cancer therapy. Small. 2018;14:1802565. doi: 10.1002/smll.201802565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu XD, Wu J, Liu YL, Saw PE, Tao W, Yu M. et al. Multifunctional envelope-type siRNA delivery nanoparticle platform for prostate cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2017;11:2618–27. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b07195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hom C, Lu J, Liong M, Luo HZ, Li ZX, Zink JI. et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles facilitate delivery of siRNA to shutdown signaling pathways in mammalian cells. Small. 2010;6:1185–90. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li X, Chen YJ, Wang MQ, Ma YJ, Xia WL, Gu HC. A mesoporous silica nanoparticle-PEI-fusogenic peptide system for siRNA delivery in cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2013;34:1391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Popat A, Hartono SB, Stahr F, Liu J, Qiao SZ, Lu GQ. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for bioadsorption, enzyme immobilisation, and delivery carriers. Nanoscale. 2011;3:2801–18. doi: 10.1039/c1nr10224a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu Q, Moore JM, Huang G, Mount AS, Rao AM, Larcom LL. et al. RNA polymer translocation with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2004;4:2473–7. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee T, Yagati AK, Pi FM, Sharma A, Choi JW, Guo PX. Construction of RNA-quantum dot chimera for nanoscale resistive biomemory application. ACS Nano. 2015;9:6675–82. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.He CB, Lu KD, Liu DM, Lin WB. Nanoscale metal-organic frameworks for the co-delivery of cisplatin and pooled siRNAs to enhance therapeutic efficacy in drug-resistant ovarian cancer cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5181–4. doi: 10.1021/ja4098862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Samanta A, Banerjee S, Liu Y. DNA nanotechnology for nanophotonic applications. Nanoscale. 2015;7:2210–20. doi: 10.1039/c4nr06283c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stulz E. DNA architectonics: towards the next generation of bio-inspired materials. Chem A Eur J. 2012;18:4456–69. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnsen KB, Gudbergsson JM, Skov MN, Pilgaard L, Moos T, Duroux M. A comprehensive overview of exosomes as drug delivery vehicles-endogenous nanocarriers for targeted cancer therapy. BBA Rev Cancer. 2014;1846:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van den Boorn JG, Dassler J, Coch C, Schlee M, Hartmann G. Exosomes as nucleic acid nanocarriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:331–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Evans BC, Nelson CE, Yu SS, Beavers KR, Kim AJ, Li HM, Ex vivo red blood cell hemolysis assay for the evaluation of pH-responsive endosomolytic agents for cytosolic delivery of biomacromolecular drugs. Jove J Vis Exp; 2013. e50166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang P, Liu G, Chen X. Nanobiotechnology: cell membrane-based delivery systems. Nano today. 2017;13:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sato V, Bolzenius JK, Eteleeb AM, Su X, Maher CA, Sehn JK. et al. CD4(+) T cells induce rejection of urothelial tumors after immune checkpoint blockade. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e121062. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aleku M, Schulz P, Keil O, Santel A, Schaeper U, Dieckhoff B. et al. Atu027, a liposomal small interfering RNA formulation targeting protein kinase n3, inhibits cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9788–98. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anfossi S, Babayan A, Pantel K, Calin GA. Clinical utility of circulating non-coding RNAs-an update. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2018;15:541–63. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ghafouri-Fard S, Ghafouri-Fard S. siRNA and cancer immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2012;4:907–17. doi: 10.2217/imt.12.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Conde J, Arnold CE, Tian FR, Artzi N. RNAi nanomaterials targeting immune cells as an anti-tumor therapy: the missing link in cancer treatment? Mater Today. 2016;19:29–43. [Google Scholar]