Abstract

In the 1990s, metered dose inhalers (MDIs) containing chlorofluorocarbons were replaced with dry-powder inhalers (DPIs) and MDIs containing hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). While HFCs are not ozone depleting, they are potent greenhouse gases. Annual carbon footprint (CO2e), per patient were 17 kg for Relvar-Ellipta/Ventolin-Accuhaler; and 439 kg for Seretide-Evohaler/Ventolin-Evohaler. In 2017, 70% of all inhalers sold in England were MDI, versus 13% in Sweden. Applying the Swedish DPI and MDI distribution to England would result in an annual reduction of 550 kt CO2e. The lower carbon footprint of DPIs should be considered alongside other factors when choosing inhalation devices.

Keywords: asthma pharmacology, COPD pharmacology, inhaler devices

Introduction

Until the early 1990s, metered dose inhalers (MDIs) that contained chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) as propellant were the most common way to administer inhaled therapy for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In 1987, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer included the phasing out of CFCs,1 warranting the development of new ways to deliver inhaled therapy for asthma and COPD. This included dry-powder inhalers (DPIs), CFC-free MDIs that used hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) as a propellant and, aqueous/soft mist inhalers.

Studies of prescription patterns in Europe have found large differences among countries in choice of inhalation device. A study published in 2011 concluded that approximately 90% of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) devices used in Sweden were DPIs, whereas in the UK, approximately 80% were MDIs.2

Unlike CFCs, HFCs are not ozone-depleting substances but they are still greenhouse gases that have a high global warming potential (GWP). In 2017, the British Thoracic Society issued a statement to encourage prescribers and patients to consider switching pressurised MDIs to non-propellant devices because of this difference in environmental impact. This statement was recently updated.3

This study aimed to compare the environmental impact of DPI and MDI combinations using calculated carbon footprint data for two DPIs, Ellipta and Accuhaler, and one MDI, Evohaler. A secondary aim was to compare the inhaler-related carbon footprint impact between England and Sweden and the potential for reduction of annual carbon footprint (CO2e) in England if the pattern of inhalation devices chosen in England were to resemble that in Sweden.

Methods

The CO2e of average use of three ICS and long-acting β2-agonist combinations Relvar* Ellipta (fluticasone furorate/vilanterol) (DPI), Seretide* Accuhaler (fluticasone propionate/salmeterol) (DPI), Seretide Evohaler (MDI) and two short acting β2-agonists Ventolin* Accuhaler (salbutamol) (MDI), and Ventolin Evohaler (MDI) in asthma and COPD have been estimated based on individually produced carbon footprints by GlaxoSmithKline and certified by the Carbon Trust. This was achieved by taking into account the whole life cycle of the device: production of pharmaceutical ingredients and the final product, packaging of product, distribution and storage, use and disposal (online supplementary file).

thoraxjnl-2019-213744supp001.pdf (6.5MB, pdf)

Data on the prescriptions dispensed of inhalation devices in England and Sweden in 2017 was collected. In England, the prescription cost analysis that included prescriptions of 49 994 877 inhalers from the National Health Service for 2017 was used,4 and in Sweden the corresponding data including 4 771 689 inhalers were obtained from IQVIVA, Stockholm, Sweden. The annual CO2e for inhalation devices in England was estimated by assuming a carbon footprint for MDIs of 20 kg CO2e and a carbon footprint for DPIs of 1 kg CO2e per inhaler; these values were approximated from carbon footprint data calculated for GlaxoSmithKline devices (online supplementary file). The potential reduction in carbon footprint was estimated by recalculating what the carbon footprint of inhalers in England would be if MDIs and DPIs were prescribed in the same proportions as in Sweden.

Results

The Evohaler MDIs had 20–30 times larger carbon footprints than the Accuhaler and Elipta DPIs (table 1). This difference was mainly related to the use phase (treatment) and the end of life phase (disposal) when the propellant is released.

Table 1.

Contribution of phases in the life cycle of different inhaler devices to their individual carbon footprint (net kg CO2e/per pack) and annual carbon footprints of each device

| RELVAR ELLIPTA 92/22 µg |

SERETIDE ACCUHALER 50/500 µg |

VENTOLIN ACCUHALER 200 µg |

SERETIDE EVOHALER 25/250 µg |

VENTOLIN EVOHALER 100 µg |

|

| Active pharmaceutical ingredients | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Manufacturing | 0.73 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 2.12 | 1.11 |

| Distribution | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| User phase | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 10.68 | 19.39 |

| End of life | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 6.08 | 7.38 |

| Net kg CO2e/pack | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 19.00 | 28.00 |

| Net kg CO2e/year | 9.5 | 11.0 | 7.3* | 234.0 | 205.0* |

*If using on average two doses per day.

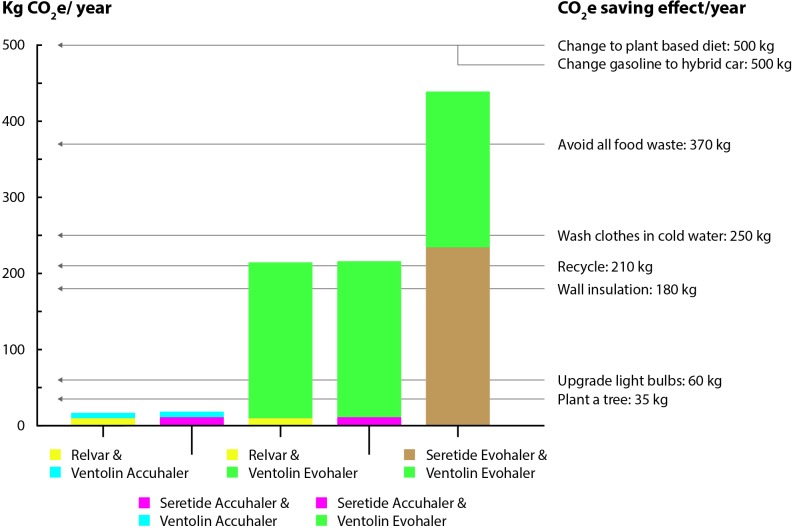

The combination of Relvar Ellipta (9.5 kg CO2e) and Ventolin Accuhaler (7.3 kg CO2e) had an annual carbon footprint of 17 kg CO2e, while the corresponding value for using the combination Seretide Evohaler (234 kg CO2e) and Ventolin Evohaler (205 kg CO2e) was 439 kg CO2e (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual carbon footprints (kg CO2e) for different combinations of Relvar, Seretide and Ventolin and annual footprint reduction of different actions*. *Wynes and Nicholas.7

In England in 2017, 70% of all inhalers sold were MDI, whereas the corresponding figure for Sweden was 13%. The difference was largest for SABA: 94 versus 10% MDIs in England and Sweden respectively, while the corresponding difference for devices that contained ICS was 62 versus 14%.

If England had the same rates of MDI use as Sweden, 550 kt CO2e would be saved annually (table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of MDI use in different classes and potential reduction in kilo tons (kt) of CO2e if changing the proportion of MDI use in the England to the level of Sweden

| England: inhalers/year | England: % MDI |

Sweden: inhalers/year | Sweden: % MDI |

England: CO2e (kt) per year |

England: potential annual reduction of CO2e (kt) |

|

| SABA | 21 931 511 | 94 | 1 477 692 | 10 | 414.00 | 350.0 |

| LABA | 700 195 | 65 | 377 415 | 2 | 9.30 | 8.4 |

| SAMA | 421 191 | 100 | No data | 100 | 8.40 | 0 |

| ICS | 6 733 445 | 94 | 765 796 | 15 | 127.00 | 101.0 |

| ICS+LABA | 14 075 067 | 47 | 1 719 428 | 13 | 140.00 | 91.0 |

| LAMA and LAMA+LABA | 6 549 448 | 0 | 428 732 | 0 | 6.55 | 0 |

| LAMA+LABA + ICS | 5211 | 99 | 2 626 | 100 | −0.10 | 0 |

| Total | 49 994 877 | 70 | 4 771 689 | 13 | 705.0 | 550.0 |

Analysis uses 2017 community prescribing data from the NHS in England (https://digital.nhs.uk/) and assumes carbon footprint of MDI is 20 kg CO2e and DPI is 1 kg CO2e. SAMA not included in analysis, as no DPI SAMA alternative is available. Potential annual reduction shows the hypothetical carbon savings if England were to prescribe the same proportions of MDI as Sweden.

DPI, dry powder inhaler; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; MDI, metered dose inhaler; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

Discussion

Using Ellipta and Accuhaler DPIs instead of Evohaler MDIs resulted in an annual carbon footprint reduction equivalent to 422 kg CO2e per patient. Applying the Swedish DPI and MDI distribution to England would result in an estimated annual reduction of 550 kt CO2e annually.

The impact of HFCs from inhalers on overall greenhouse gas emissions can be viewed from many perspectives. Internationally, HFC release from MDIs in 2014 was equivalent to 0.013 gt CO2e, which was about 3% of global GWP-weighted CO2e emissions of HFCs.5 HFCs are also used as refrigerants in refrigeration, air-conditioning and heat pump equipment (80%); as blowing agents for foams (11%); as solvents and in fire extinguishers (5%).6 From an individual patient’s perspective, a comparison of Ventolin and Seretide Evohalers with Relvar Ellipta and Ventolin Accuhaler could save 422 kg CO2e per year per patient. This is similar to the per capita carbon reductions obtained if changing from a meat-based to a plant-based diet.7 This calculation was based on a usage of two doses SABA per day.8 In patients that are very well controlled and therefore not using any SABA at all the difference was 234 kg CO2e per year.

We found a large difference between England and Sweden in the distribution of inhalation devices. This is in accordance with previous data.2 The reason for this difference is not entirely clear but could be related to marketing strategies and prescribers’ and patients’ biases.2 In England, the carbon footprint of the National Health Service (NHS) is ≈23 mt CO2e. Pharmaceuticals procurement is 16% of the footprint, one quarter of which comes from MDIs.9 Other carbon footprint sources include building and energy and travel (4.6 and 2.8 mt CO2e, respectively). The predicted reduction of 550 kt CO2e annually that we calculated by applying the Swedish distribution of inhalation devices to the population in England thus corresponds to approximately 2.6% of the total carbon footprint for NHS England.9 The main weakness of this analysis was that the analysis was limited to GlaxoSmithKline devices as accurate carbon footprint data were not available from other manufacturers.

Key considerations for inhaler selection include healthcare professional knowledge of all the devices; inhalation manoeuvre achieved; airway disease severity, patient’s ability to use their device correctly and their personal preferences.10 Thus the final choice of inhaler includes many factors, such as the fundamental efficacy of the molecules, patient-use factors, and the environmental burden. It should be noted that any change from an MDI to DPI device in clinical practice should be based on a clinical assessment and needs to be actively supported by appropriate programmes of education and assessment to ensure correct inhaler technique.

We conclude that Ellipta and Accuhaler DPIs have considerably lower carbon footprints than Evohaler MDIs, at both an individual and a national level. The lower carbon footprint of DPIs should be considered alongside other factors for patients who are able to use these devices effectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Luke Hedger, GlaxoSmithKline plc., in analysing the inhaler carbon footprint data for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @DrAlexWilkinson

Contributors: The authors declare the following contributions to this study: AJKW, CJ, ML and RH developed the study concept; AJKW, CJ and RH were involved in the data analysis; all authors contributed to drafting and finalising the manuscript and approved the final version for submission; CJ is the guarantor, taking responsibility for work and/or conduct of study, full access to data, and control of decision to publish.

Funding: Editorial support (in the form of collating author comments, assembling tables/figures, grammatical editing and referencing) was provided by Jenni Lawton, PhD, of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications (Macclesfield, UK), and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare the following: CJ reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and TEVA outside the submitted work; MH reports honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline for presenting scientific data on climate change; AJKW has nothing to disclose; RH and RS are GlaxoSmithKline employees and hold GlaxoSmithKline stocks/shares, ML is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. United Nations Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Available: http://www.un-documents.net/mpsdol.htm [Accessed 7 Nov 2018].

- 2. Lavorini F, Corrigan CJ, Barnes PJ, et al. Retail sales of inhalation devices in European countries: so much for a global policy. Respir Med 2011;105:1099–103. 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. British Thoracic Society The environment and lung health. Available: https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/governance-and-policy-documents/position-statements/environment-and-lung-health-position-statement-2019/ [Accessed 3 May 2019].

- 4. NHS Digital Prescription cost analysis: England, 2017, 2018. Available: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/prescription-cost-analysis/prescription-cost-analysis-england-2017 [Accessed 7 Nov 2018].

- 5. Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Report of the UNEP medical technical options Committee, 2014 assessment. Available: http://conf.montreal-protocol.org/meeting/oewg/oewg-36/presession/Background%20Documents%20are%20available%20in%20English%20only/MTOC-Assessment-Report-2014.pdf [Accessed 11 Jan 2019].

- 6. Climate & Clean Air Coalition Hydrofluorocarbons (HFC). Available: https://www.ccacoalition.org/fr/slcps/hydrofluorocarbons-hfc [Accessed 19 of Aug 2019].

- 7. Wynes S, Nicholas KA. The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environ Res Lett 2017;12 10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vestbo J, Papi A, Corradi M, et al. Single inhaler extrafine triple therapy versus long-acting muscarinic antagonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRINITY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:1919–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30188-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. NHS England sustainable development unit Reducing the use of natural resources in health and social care 2018 report. Available: https://www.sduhealth.org.uk/policy-strategy/reporting/natural-resource-footprint-2018.aspx [Accessed 20 Jun 2019].

- 10. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network British guideline on the management of asthma, 2019. Available: https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/standards-of-care/guidelines/btssign-british-guideline-on-the-management-of-asthma/ [Accessed 14 Dec 2018].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

thoraxjnl-2019-213744supp001.pdf (6.5MB, pdf)