Abstract

Pharmacological interventions of diabetic gastroparesis (DG) constitute an essential element of a patient’s management. This article aimed to systematically review the available pharmacological approaches of DG, including their efficacy and safety. A total of 24 randomised clinical trials (RCTs) that investigated the efficacy and/or safety of medications targeting DG symptoms were identified using several online databases. Their results revealed that metoclopramide was the only approved drug for accelerating gastric emptying and improving disease symptoms. However, this medication may have several adverse effects on the cardiovascular and nervous systems, which might be resolved with a new intranasal preparation. Acceptable alternatives are oral domperidone for patients without cardiovascular risk factors or intravenous erythromycin for hospitalised patients. Preliminary data indicated that relamorelin and prucalopride are novel candidates that have proven to be effective and safe. Future RCTs should be conducted based on unified guidelines using universal diagnostic modalities to reveal reliable and comprehensive outcomes.

Keywords: Gastroparesis, Diabetes Mellitus, Diabetes Complications, Randomized Controlled Trial, Metoclopramide, Domperidone, Relamorelin

Gastrointestinal neuropathies in patients with diabetes represent vital aspects of the chronic course of the disease. They may include oesophageal dysmotility, gastroparesis, small bowel dysmotility or diarrhoea and fecal incontinence.1 More precisely, reduced gastric emptying (GE) has been frequently reported in diabetic patients having gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy.2 Delayed GE was first reported by Boas in 1925, which was subsequently termed gastroparesis diabeticorum by Kassender in 1958.3,4 A symptom entailing contractile, functional, sensory and electrical dysfunction of the stomach was then identified and described as diabetic gastroparesis (DG).5 This can be perceived as chronic delayed GE associated with nausea, vomiting, postprandial fullness, weight loss, anorexia and abdominal pain without evidence of mechanical obstruction. Furthermore, DG patients usually have poor quality of life and poor glycaemic control; in addition, the disease imposes a significant financial burden on healthcare systems.6

The prevalence of DG varies in the literature; in general, the risk of gastroparesis is higher in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) compared to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). DG disease prevalence in T1DM was found to be 4.8% based on diabetes registries while tertiary medical centres have reported a prevalence of up to 64%.7–9 In T2DM, DG is reported in 10.8–30% of patients.10,11 Gender differences were observed in several publications where females had higher prevalence rates than males.8,10,12 Poorly-controlled diabetes, higher glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), long duration of diabetes and the presence of comorbidities have been consistently reported as independent risk factors of DG.8,10 Similarly, in an epidemiological study involving 8,657 individuals in Australia, patients with poor glycaemic control had increased prevalence of upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms.12 Additionally, the probability of developing DG symptoms increased with advanced age, with a mean age of onset at approximately 34 years.5

The diagnosis of DG may remain elusive until the development of complications. To avoid this delay, a precise medical history of the timing of symptoms (i.e. vomiting and satiety) in relation to meals, diet history, symptom progression and diabetes control should be carefully assessed. Severity of DG symptoms is evaluated using the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI), which can be utilised to rate changes in symptoms in clinical studies either by the patient or the physician on a scale ranging from zero (no symptoms) to six (very severe symptoms).13 Furthermore, gastric obstruction can be excluded using abdominal radiography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans. Consequently, a DG diagnosis is confirmed by means of three main diagnostic tests. The first method is gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES), which is a non-invasive method employing a radio-labelled solid meal (mostly using 99mTc-sulfur) followed by scanning the stomach at one, two and four hours after the meal.14 The second method is the stable isotope breath test (gastric emptying breath test [GEBT]). After ingestion of meals with 13C-labelled substrates, such as octanoic acid and Spirulina platensis, the isotope is absorbed in the small intestine and metabolised to 13carbon dioxide and exhaled through the lungs. Finally, a recent diagnostic modality is a swallowed wireless motility capsule wherein a specialised sensor is used to measure pressure, temperature and pH.15

GE in patients with DG is challenging in terms of treatment. This is particularly evident because optimum glycaemic control should be achieved in poorly-controlled diabetic patients. Dietary modifications, such as replacing solid food with a soft and liquid diet, are required. Several pharmacologic options are available although the efficacy and safety of these medications vary. Usually, patients with mild to moderate symptoms are managed by prokinetics and antiemetics. However, disease burden in patients experiencing severe symptoms is difficult to manage. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the most appropriate therapeutic options bearing in mind the prevention of potential gastrointestinal complications in DG patients including gastroesophageal reflux disease, bacterial and fungal infections of the gastrointestinal tract and intestinal dysmotility. In this context, this article aimed to systematically review the available approaches for the pharmacotherapy of DG, including their efficacy and safety and emphasising their roles in patients with different disease severities.

Methods

Based on the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses statement, this systematic review was conducted on investigated medications of diabetic patients with DG.16 In the context of DG, a medication’s efficacy targets the severity of symptoms and/or GE while safety deals with the reported adverse events (AEs) in the groups under investigation.

MEDLINE® (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), EMBASE (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands), Cochrane Library (Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA) and Google Scholar (Google LLC, Menlo Park, California, USA) databases were used to search for randomised clinical trials (RCTs) that assessed the efficacy and/or safety of medications used for the management of DG. Although the last search was performed until April 2019, there was no time limit set for the included trials. The search strategy used specific keywords based on a Patient/Problem, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome strategy, utilising relevant subject headings and Boolean Operators. These databases were searched with the terms “diabetes” or “diabetic”, “gastroparesis” or a combination of the two, “prokinetics” or “prokinetic”, “metoclopramide” or “domperidone” or “erythromycin” or “cisapride” or “bethanecol” or “tegaserod”, “Motilin agonist” or “ghrelin agonist” or “5-HT4 agonist” (5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4) and “antiemetic” or “phenothiazine” or “serotonin 5-HT3 Receptor Antagonist” or “antihistamine”. Only RCTs with the following characteristics were included in this review: (1) DG had to be diagnosed based on the exclusion of gastrointestinal obstruction; (2) studies should have allocated at least two groups for comparing the outcomes of a single medication versus placebo or another medication; (3) the allocated patients may be adults or children with T1DM or T2DM; (4) the study should be published in a peer-reviewed journal and written in English; (5) the primary outcomes of the RCT should include changes in the scores of the severity of symptoms (as indicated by the GCSI scale, visual analogue scores, etc.) in addition to changes in GE (assessed by ultrasound, GES, GEBT or the swallowed wireless motility capsule); (6) all changes should have been initially measured at baseline and reassessed during the course of the study after the administration of medication(s); (7) the AEs should have been assessed in patients in accordance with the physical examination or patient self-reported data; and (8) changes in GE as retrieved from GEBT may be reported as gastric half-emptying time (T½). Studies recruiting a population or subpopulation of healthy individuals or presenting comorbidities with serious conditions rather than diabetes were excluded. Additionally, studies were ineligible if they were non-randomised prospective investigations, retrospective studies, narrative reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Finally, a comprehensive search for on-going clinical trials for each medication in ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) was performed. A medication was considered novel when its relevant phase 2 RCT was published in 2010 or later.

Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts obtained by the database search process. Additionally, the reference lists of the identified RCTs were screened for additional eligible studies. The obtained publications were uploaded to EndNote, Version X7 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA) and all duplicate publications were omitted. Decisions regarding the included studies were approached via consensus and any disagreement was resolved via discussion. All data were extracted into a specifically-designed Excel spreadsheet, Version 2016 (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, Washington, USA), that included: 1) study data (name of the first author, year of publication, study design, study duration and country); 2) patients’ data (gender, total sample size, age, type of diabetes, glycaemic indicators [e.g. HbA1c] and baseline parameters used to confirm DG symptoms); 3) study groups and interventions (medication(s) used and/or placebo, dosage and methods and duration of administration); 4) the efficacy of medication(s) (changes in severity scores and/or GE in relation to other groups and baseline values when appropriate); and 5) the safety of medication(s) (reported AEs following drug administration).

The methodological quality of the included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane’s Risk of Bias Tool.17 The domains assessed in each trial included performance bias, selection bias, detection bias, attrition bias and other biases. The results of the assessment process were either reported as “low risk”, “high risk” or “unclear”. Trials were labelled “unclear” when no data were available in the RCT about the domain under investigation. All data were entered and graphically presented using RevMan, Version 5.3 (Cochrane, London, England).

Results

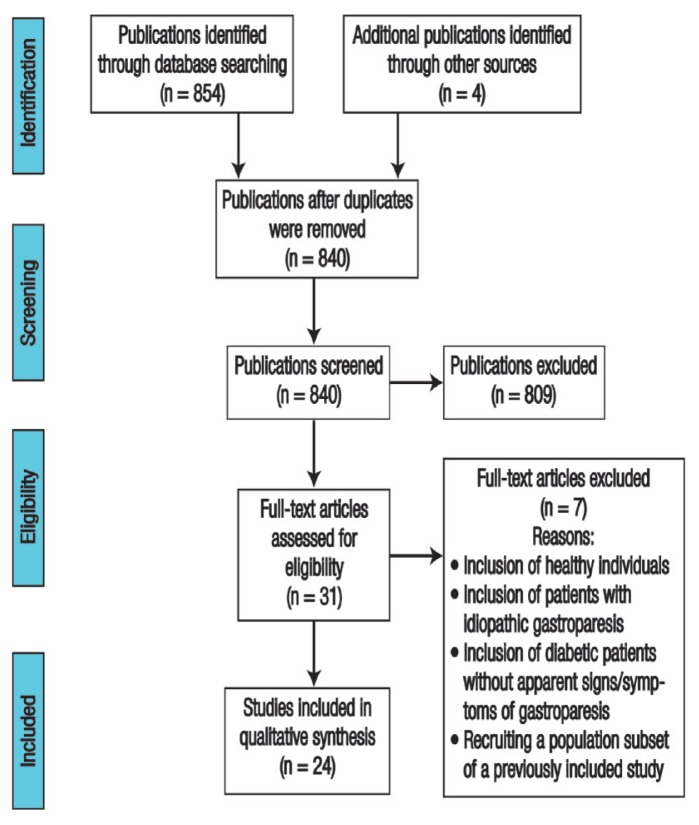

A total of 854 publications were initially obtained in the specified databases by using the relevant keywords. Four studies were additionally identified from Google search (Google LLC). Following the removal of 18 duplicate publications, the titles and abstracts of 840 studies were screened and 809 were excluded. The full-text versions of the remaining 31 articles were thoroughly checked for eligibility. Nonetheless, seven articles were excluded due to the inclusion of healthy individuals, inclusion of patients with idiopathic gastroparesis, inclusion of patients with diabetes but without signs/symptoms of gastroparesis or a separate trial which included a population subset of an already included study.18–24 Finally, a total of 24 RCTs were included in this qualitative review [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the search process used to identify randomised clinical trials investigating the efficacy and/or safety of medications targeting diabetic gastroparesis symptoms (N = 24).

A total of 2,309 patients, of which the majority (65.22%) were female, were included in all studies which were published between 1982 and 2017. Only one RCT recruited paediatric patients; adults were included in the remaining investigations.25 Studies were conducted in European countries, at multiple sites in Europe and the USA or only in the USA.25–33 Patients were diagnosed with T1DM exclusively in nine studies,25,30,31,34–39 only T2DM in one study and both types in the remaining trials [Table 1].40

Table 1.

Summary of the included randomised clinical trials investigating the efficacy and/or safety of medications targeting diabetic gastroparesis symptoms21,25–45,59,66

| Author and year of study | Study duration | Country | Gender | Age in years | Diabetic indicators | Gastroparesis indicators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | ||||||

| Barton et al.66 (2014) | 4 weeks | USA | 32 | 47 | 79 | 18–60 | N/A |

|

| Braden et al.30 (2002) | 12 months | Germany | 5 | 14 | 19 | 56–72 | HbA1c: 7.1–8.2% |

|

| Camilleri et al.42 (2017) | 3 months | USA | 148 | 245 | 393 | 20–76 | HbA1c: 5.2–11.0% |

|

| Desautels et al.59 (1995) | NA | USA | 10 | 0 | 10 | 26–70 | HbA1c: 6.7–12.9% |

|

| Ejskjaer et al.28 (2009) | 10 months | Denmark | 5 | 5 | 10 | 46–56 | HbA1c: 9.5 ± 2.2 % |

|

| Ejskjaer et al.29 (2010) | 17 months | Denmark | 25 | 51 | 76 | 18–80 | HbA1c: 6.6–10.9% |

|

| Ejskjaer et al.32 (2013) | 13 months | 18 centres in different countries | 32 | 60 | 92 | 20–70 | HbA1c: 6.5–10.2% |

|

| Erbas et al.26 (1993) | 9 weeks | Turkey | 4 | 9 | 13 | 19–68 | Self-reported treatment by an oral diabetic agent and/or insulin |

|

| Franzese et al.25 (2002) | 8 weeks | Italy | 14 | 14 | 28 | 6–16.9 | Insulin dependence for a mean of 5 years |

|

| Hellström et al.39 (2016) | 4 weeks | USA | 5 | 5 | 10 | 18–70 | N/A |

|

| Lehmann et al.31 (2003) | 7 months | Switzerland | 4 | 4 | 8 | 28–63 | HbA1c: 8.0 ± 1.3% |

|

| Lembo et al.41 (2016) | 14 months | USA | 67 | 137 | 204 | 18–75 | HbA1c: ≤11% |

|

| McCallum et al.35 (1983) | 3 weeks | USA | 16 | 28 | 44 | 21–67 | Insulin dependence for 12.6 years |

|

| McCallum et al.21 (2007) | 12 weeks | USA | 139 | 253 | 392 | 18–70 | HbA1c: 7.7 ± 1.7% |

|

| McCallum et al.43 (2013) | 22 months | USA | 56 | 145 | 201 | 42–66 | HbA1c: 7.8 ± 1.5% |

|

| Murray et al.27 (2005) | N/A | UK | 5 | 5 | 10 | 36–63 | HbA1c: ≤11% |

|

| Parkman et al.33 (2014) | 6 weeks | USA (in 6 centres) | 41 | 48 | 89 | 18–82 | N/A |

|

| Parkman et al.44 (2015) | 4 weeks | USA | 83 | 202 | 285 | 18–75 | Self-reported treatment by an oral diabetic agent and/or insulin |

|

| Patterson et al.37 (1999) | 4 weeks | USA | 33 | 62 | 95 | 19–69 | N/A |

|

| Ricci et al.36 (1985) | 6 weeks | USA | 6 | 7 | 13 | 24–73 | Insulin dependence for 12.5 years |

|

| Shin et al.38 (2013) | 6 months | USA | 2 | 8 | 10 | 31–65 | HbA1c: ≤11.3% |

|

| Shin et al.40 (2013) | 3 months | USA | 0 | 10 | 10 | 36–60 | HbA1c: 7.2 ± 0.4% |

|

| Silvers et al.45 (1998) | 4 weeks | USA | 66 | 142 | 208 | 19–76 | N/A |

|

| Snape et al.34 (1982) | 6 weeks | USA | 5 | 5 | 10 | 21–49 | Insulin dependence for 16.2 ± 2.4 years |

|

N/A = not available; GCSI-DD = The Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index-Daily Diary; GE = gastric emptying; 13C-GEBT = 13C-spirulina gastric emptying breath test; T½ = half-emptying time; HbA1C = glycosylated haemoglobin; DG = diabetic gastroparesis; min = minutes; GES = gastric emptying scintigraphy; GMBT = gastric motility breath test; TSS = total symptom score; NVFP = nausea, vomiting, fullness, and pain.

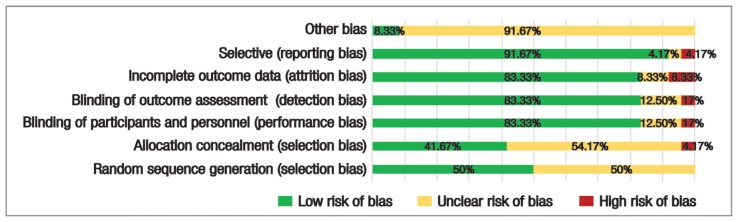

Figure 2 shows the summary of risk of bias assessment. Random sequence generation was generated by a computer software in eight trials and an Interactive Voice Response System was used in four trials.27,29–33,38,40–44 Since the method of randomisation was inexplicitly mentioned in the remaining RCTs, they were assessed as “unclear”. Participants’ allocation was concealed from the investigators in ten trials, while selection bias was apparent in one trial, owing to the randomisation using an incomplete block method.29,32,35,36,38–44 The method of concealment was unclear in the remaining trials. Both performance and detection biases were evident in a trial conducted by Silvers et al. since the investigators were not blinded to the patients receiving the intervention.45 Intention-to-treat analysis was performed in eight trials in order to investigate the efficacy of interventions following withdrawal of a number of participants.33,37,39,41,43–46 Patients’ withdrawal had not affected the comparability between groups as explored by statistical analyses in the remaining trials [Table 2].

Figure 2.

A summary of risk of bias assessment for the included randomised clinical trials (N = 24).

Table 2.

The outcomes of randomised clinical trials investigating traditional and novel medications for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis21,25–45,59,66

| Author and year of study | Study groups and INT | Efficacy on gastroparesis symptoms | Efficacy on GE | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine D2 receptor antagonist | ||||

| Snape et al.34 (1982) |

|

|

|

|

| McCallum et al.35 (1983) |

|

|

|

|

| Ricci et al.36 (1985) |

|

|

|

|

| Parkman et al.33 (2014) |

|

|

|

|

| Parkman et al.44 (2015) |

|

|

|

|

| Patterson et al.37 (1999) | The following regimens were given for 4 weeks:

|

|

|

|

| Silvers et al.45 (1998) |

|

|

|

|

| Franzese et al.25 (2002) |

|

|

|

|

| Erbas et al.26 (1993) | The following regimens were given for 3 weeks, then 3 weeks washout and 3 weeks cross-over:

|

|

|

|

| Ghrelin receptor agonist | ||||

| Murray et al.27 (2005) |

|

|

|

|

| Ejskjaer et al.28 (2009) |

|

|

|

|

| Ejskjaer et al.29 (2010) |

|

|

|

|

| Ejskjaer et al.32 (2013) |

|

|

|

|

| McCallum et al.43 (2013) |

|

|

|

|

| Shin et al.38 (2013) |

|

|

|

|

| Shin et al.40 (2013) |

|

|

|

|

| Lembo et al.41 (2016) |

|

|

|

|

| Camilleri et al.42 (2017) |

|

|

|

|

| Motilin receptor agonist | ||||

| Desautels et al.59 (1995) |

|

|

|

|

| McCallum et al.21 (2007) |

|

|

|

|

| Barton et al.66 (2014) |

|

|

|

|

| Hellström et al.39 (2016) |

|

|

|

|

| 5-HT4 receptor agonist | ||||

| Braden et al.30 (2002) |

|

|

|

|

| Lehmann et al.31 (2003) |

|

|

|

|

INT = interventions; GE = gastric emptying; GES = gastric emptying scintigraphy; NA = not available; TSS = total symptom score; CFB = change from baseline; CNS = central nervous system; min = minutes; VAS = visual analogue score; AEs = adverse events; GCSI = Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index; GSA = Gastroparesis Symptom Assessment; GMBT = gastric motility breath test; GSDD = gastroparesis symptom daily diary; CFB = change from baseline; GEBT = gastric emptying breath test; SC = subcutaneous; DD = daily diary; NVFP = nausea, vomiting, fullness and pain.

TRADITIONAL MEDICATIONS

Dopamine D2 receptor antagonists

Metoclopramide has dual actions on the brainstem and peripheral nerves as a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist and serotonin (i.e. 5-HT4) receptor agonist. The main effects on the gastrointestinal tract are exerted by increasing antral contraction by releasing acetylcholine from enteric neurons.47 In DG patients, early trials indicated significant improvements in the scores of nausea, fullness and bloating after three weeks of metoclopramide oral administration as compared to the placebo.35,36 In addition, GE improved significantly and consistently in all trials of oral regimens assessed by GES.34–36 Therefore, it was the sole drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of DG. Rather than oral administration, in terms of improving GCSI scores, more recent RCTs have shown superior efficacy of nasal spray preparations.33,44 However, some AEs were reported in other trials, particularly in comparative ones which were conducted for more than four weeks.26,33,37 These AEs include anxiety, depression, somnolence, headache and leg cramps. Furthermore, there are some concerns about the development of tardive dyskinesia with the chronic use of metoclopramide.48 Diabetes itself may be independently associated with the risk of tardive dyskinesia.49 Therefore, this medication received a ‘black box warning’ from the FDA. Collectively, recommendations indicate the use of metoclopramide for no longer than 12 weeks.50

Therefore, alternative medications with high efficacy and safety have been studied. Domperidone is another dopamine D2 receptor antagonist which is effective against nausea and vomiting with a better safety profile than metoclopramide. Patterson et al. showed that domperidone was associated with less frequent central AEs compared to metoclopramide.37 Similarly, domperidone ameliorated nausea and early satiety compared to placebo in adults and cisapride in children with DG.25,45 It can be initially administered three times daily at a dose of 10 mg, which is increased to 20 mg at bedtime. Early prospective investigations conducted almost three decades ago revealed that DG symptoms improved significantly after six months or one year of treatment.51,52 Additionally, it improved the quality of life of patients in a subsequent retrospective analysis.53 However, domperidone may be associated with a risk of cardiac arrhythmia and may cause QT prolongation.54 Therefore, recommendations based on a moderate level of evidence indicate performing a baseline electrocardiogram and a cessation of treatment if the corrected QT is more than 470 and 450 ms in males and females, respectively. Moreover, a follow-up electrocardiogram along the course of treatment is advised.55

Ghrelin and ghrelin receptor agonists

Early studies have shown favourable implications of ghrelin in the treatment of gastroparesis as it modulates energy homeostasis and gastrointestinal motility.27 This was evident in ten patients with DG using a test meal of rice pudding where ghrelin infusion caused a significant increase in GE independent of cardiovagal tone.27 However, the therapeutic effects of ghrelin were limited by its relative plasma instability and short half-life.56 Thus, several synthetic ghrelin analogues were investigated for their clinical potential.

TZP-101 (i.e. ulimorelin) is a macrocyclic ghrelin receptor analogue which has been investigated in patients with DG in a phase 1 trial in Denmark.28 TZP-101 infusion (given at 80, 160, 320, or 600 μg/kg in a crossover manner) caused 20% reduction in gastric T½ of solids compared to a placebo; however, no apparent effects were noted on postprandial symptoms.28 A phase 2 trial conducted by the same team revealed that the infusion of 80 μg/kg TZP-101 caused a significant reduction in severity of several symptoms including vomiting, loss of appetite and reduction of the GCSI scores (25% versus 8% among patients allocated to placebo), although no differences were reported in gastric T½.29

Consequently, TZP-102 was developed as an oral preparation. A phase 2a trial was performed in 2013 to assess the impact of a 28-day TZP-102 regimen for doses ranging between 10 and 40 mg versus a placebo. Ejskjaer et al. found that all doses (combined) significantly alleviated DG symptoms, but with no remarkable effects on GE indices.32 Similarly, a phase 2b trial, which administered TZP-102-CL-G003 and TZP-102-CL-G004 for 12 weeks, emphasised the lack of improving effects on the Gastroparesis Symptom Daily Diary scores as well as GE analysis compared to a placebo.43 In addition, the investigations of TZP-102-CL-G004 were terminated at an early stage due to lack of efficacy in DG patients.

Motilin receptor agonists

Erythromycin has been well-established for its prokinetic action since its introduction six decades ago.57 Its motilin agonistic action promotes peristaltic movement and enhances GE through the induction of phase III contractions of the migrating motor complex. Thus, it increases gastric antral contraction. Early studies revealed that acute intravenous and chronic oral administration for four weeks led to a significant reduction in the total symptom score in DG patients, which may be superior to the effect of metoclopramide.26,58 Desautels et al. reported significant GE acceleration via a single dose of 250 mg with no apparent side effects in diabetic patients.59 However, subsequent studies have shown that erythromycin was associated with tachyphylaxis, whereby its prokinetic effect may be lost after 48 hours of treatment.60 In addition, its venous administration may be associated with serious AEs such as ventricular arrhythmia and can interact with other medications due to inhibition of cytochrome P450 C3A4.61,62

Additional medications without antibiotic activities and avoiding the previously-mentioned AEs need to be developed. Mitemcinal is another motilin agonist which has been tested in a 12-week double-blind RCT.46 Although there was evidence of GE improvements in patients with non-delayed GE, the results showed no significant differences in the symptoms of DG.

5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 agonists

Cisapride is a traditional non-selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist which causes increased muscular contraction through cholinergic pathways. Two RCTs have shown that the chronic use of this medication (for at least seven months) reduces GE time in patients with DG with no remarkable effects on their glycaemic control.30,31 However, both trials excluded patients with prolonged QTc at the initial recruitment. Given that cisapride administration can activate the Human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channels and may consequently lead to QT prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias and syncope, it has been withdrawn from the market in several countries.63 Similarly, the use of tegaserod (another 5-HT4 agonist) has been suspended since 2007 owing to its association with ischaemic cardiovascular events.64

NOVEL AND INVESTIGATIONAL MEDICATIONS

Ghrelin and ghrelin receptor agonists

RM-131 (i.e. relamorelin), the most recently investigated member of the ghrelin analogue family, has provided promising outcomes. Initially, Shin et al. tested the efficacy of subcutaneous injections of RM-131 in 10 patients with T1DM in a double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled RCT and assessed the symptoms of DG using the GCSI score and GE using scintigraphy.38 Results revealed that gastric T½ was significantly accelerated at one and two hours after meals compared to a placebo along with significant improvements in the average symptoms scores. Similar results were reported by Shin et al. in an RCT conducted among female patients with T2DM.40 More recent data from placebo-controlled RCTs indicated that subcutaneous injection of RM-131 twice daily had the most remarkable impact on reducing the frequency and severity of DG symptoms besides GE acceleration.41,42 Additionally, these regimens were safe and well-tolerated in all trials. Phase 3 clinical trials are on-going concerning this novel medication [Table 3].

Table 3.

Ongoing clinical trials which investigate candidate medications for diabetic gastroparesis

| Candidate drug | Mechanism of action | Disease | Intervention | Clinicaltrials.gov identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prucalopride (Resotran™ [Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium]) | 5-HT4 agonist | DG | 2 × 2 mg tablets of prucalopride or placebo given once daily for 28 days | NCT02031081 |

| Velusetrag (TD-5108) | 5-HT4 agonist | DG and IG | Velusetrag 5, 15, 30 mg capsules once daily versus placebo for 12 weeks | NCT02267525 |

| RQ-00000010 | 5-HT4 agonist | Gastroparesis | The intervention will be given once daily at doses of either 10, 50, 100 μg orally for 2 weeks versus placebo | NCT02838797 |

| TAK-906 | Dopamine D2 receptor antagonist | DG and IG | TAK-906 5, 25, and 100 mg capsules versus placebo for 9 days | NCT03268941 |

| Sitagliptin (MK-0431-075) | DPP-4 inhibitor | DG | 100 mg sitagliptin once daily for 2 days versus placebo | NCT02324010 |

| VLY-686 (Tradipitant) | Neurokinin 1 antagonist | Gastroparesis | VLY-686 oral capsule once daily for 4 weeks versus placebo | NCT02970968 |

| Relamorelin (RM-131) | Selective ghrelin receptor agonist | DG | Relamorelin 10 μg SC injection twice daily for 12 weeks versus placebo | NCT03285308 |

| Relamorelin 10 μg SC injection twice daily for 52 weeks versus placebo | NCT03383146 |

5-HT4 = 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4; DG = diabetic gastroparesis; IG = idiopathic gastroparesis; DPP-4 = dipeptidyl peptidase-4; SC = subcutaneous.

Motilin receptor agonists

Camicinal (i.e. GSK962040) is a novel small-molecule motilin agonist which causes GE acceleration in healthy individuals.65 The pharmacokinetic characteristics of camicinal in the latter populations were similar to those in patients with T1DM, causing a significant reduction of gastric T½ (65% improvement) following a single dose of up to 125 mg compared to a placebo (52 versus 147 minutes; P < 0.05) despite a lack of remarkable symptomatic improvements.39 However, in a double-blind, phase 2 RCT, Barton et al. found a significant amelioration of fullness and early satiety after camicinal administration (10 and 50 mg) for four weeks.66

5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 agonists

There are multiple on-going investigations concerning new 5-HT4 receptor agonists that exert beneficial outcomes on the gastrointestinal tract without prominent AEs on cardiac muscle. However, these trials are either performed on patients with idiopathic gastroparesis or their outcomes have not been published yet. Revexepride is a specific agonist that has been tested in an RCT on diabetic and non-diabetic patients with gastroparesis.22 There were no significant improvements in GCSI scores, GE or quality of life of patients allocated to the intervention group versus a placebo.22 Prucalopride is a selective 5-HT4 agonist which significantly reduced GEBT T½ compared to a placebo (P < 0.050) as well as GSCI scores of bloating/distension (P < 0.001), nausea/vomiting (P = 0.010) and fullness (P < 0.001) when it was given at a dose of 2 mg once a day for four weeks.67 A phase 2 trial in DG patients was completed with no reported results so far [Table 3]. Likewise, velusetrag, which has been proven for its GE-accelerating effects in patients with constipation, is being investigated in patients with gastroparesis.

Discussion

DG is a relatively common complication among diabetic patients. Nevertheless, there is no consensus on the optimal management approach. Hence, several medications have been tested to relieve the symptoms in individuals with an established health burden. The current article aimed to review the best level of evidence, namely RCTs, which tested the efficacy and safety of medications targeting DG. Results showed multiple safety concerns of the currently used drugs. While metoclopramide is the only FDA-approved drug, other traditional drugs have been withdrawn from the markets of several countries owing to risky complications, mostly cardiovascular, in diabetic patients. Current efforts are aimed at developing novel medications and/or new safe preparations of traditional drugs.

Metoclopramide can interfere with emesis through its action on the central nervous system and increase gut motility via its prokinetic effect. Due to the risk of AEs such as tardive dyskinesia, it has been traditionally prescribed at the lowest effective dose for short periods of time. The novel intranasal preparation is seemingly more practical due to the intolerability of oral medications in DG patients with severe nausea and vomiting. For those who are unable to use metoclopramide, domperidone has recently been granted FDA’s expanded access investigational new drug application in adults with gastroparesis.68 This drug should be prescribed to manage severe symptoms in patients whom the potential benefits of the medication may justify its potential risks. Although the impact on the central nervous system is not apparent, domperidone still has cardiovascular risks owing to its tendency of causing a prolonged QTc interval. Seemingly, intravenous erythromycin is warranted in hospitalised patients who need intravenous therapy as they are continually monitored for any AEs.69

Recent trials showed promising effects of the novel ghrelin receptor agonist relamorelin, the motilin receptor agonist camicinal and the 5-HT4 agonist prucalopride. Subcutaneous relamorelin has been effective and safe in healthy individuals and in DG patients has been shown to accelerate GE and induce antral contraction.42,70 The most effective doses are 10 and 20 μg while the on-going RCTs use the smaller dose to assess its efficacy in managing gastroparesis symptoms. Camicinal can be considered an attractive candidate for the treatment of DG as it showed GE acceleration in a dose-dependent manner in healthy and diabetic patients at a minimum dose of 125 mg.39,71 Owing to small sample sizes and its administration at a single dose, the conducted RCTs failed to demonstrate significant effects on DG symptoms. As such, further trials are warranted giving due consideration to using multiple-dose regimens and recruiting larger samples. Prucalopride is approved in many countries for the treatment of chronic constipation and its preliminary favourable actions on patients with gastroparesis may be attributable to its high affinity to 5-HT4 receptors with no effects on hERG channels.67,72

The efficacy of prokinetics in diabetic patients may be affected by other factors which can decrease GE. For instance, the patient’s diabetologist should be consulted regarding the use of GLP-1 analogues such as liraglutide and exenatide as well as incretin-based drugs (e.g. pramlintide) as they may interfere with GE.73,74 Furthermore, while there is no confirmative evidence of the relationship between long-term improved glycaemic control, the symptoms of DG and the rates of GE, studies have shown that acute hyperglycaemia can slow GE in diabetic patients.75,76 It is worth noting that a diet rich in both fibre and fat can delay GE. As such, the main essence of dietary interventions should be consuming small and frequent meals which are low in fat and fibre.50,77 Additionally, a recent RCT has indicated the significance of small-particle size diets in reducing the severity of key symptoms of DG including postprandial fullness, nausea/vomiting and bloating.78

Ethnic-based differences in disease presentation have been reported in a retrospective analysis of adult patients in the National Institutes of Health Gastroparesis Consortium registries, where non-Hispanic blacks with DG had more severe symptoms (nausea/vomiting) and more frequent hospitalisation rates compared to non-Hispanic whites.79 The increased severity of DG symptoms in non-whites was also reported in other cross-sectional studies.80,81 Additionally, Hispanics were more likely to develop gastroparesis secondary to diabetes than non-Hispanic whites who experienced idiopathic gastroparesis.79 Therefore, domperidone treatment and peripherally inserted catheters were less used in Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic whites. Nonetheless, the therapeutic effects based on racial differences were not exclusively investigated in RCTs. Studies employing a large proportion of white patients of Caucasian heritage (>80%) showed acceptable efficacy and safety outcomes after using ulimorelin, relamorelin and domperidone.29,41,45

The use of antiemetics predominantly focuses on symptomatic management. Antihistamines (i.e. promethazine) and phenothiazines (i.e. prochlorperazine) are frequently prescribed, yet they may interact with the prokinetics particularly if the medications are metabolised through the CYP450 pathway. Serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, such as ondansetron and dolasetron, may be used in emergency settings when other therapies fail to relieve nausea; little is known about their efficacy in gastroparesis secondary to diabetes.82 Moreover, patients with profound nausea and vomiting may benefit from synthetic cannabinoids, including dronabinol and nabinol, although they showed variable pharmacokinetic profiles.83 They may be associated with a risk of hyperemesis on withdrawal and were not previously tested in DG patients.84

Recently, aprepitant, a neurokinin 1 (NK-1) receptor antagonist, has shown encouraging outcomes. While it was originally used for managing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, a 4-week, double-blind multicentre trial revealed that aprepitant ameliorated the severity of nausea, vomiting and all GCSI symptoms in patients with all-cause gastroparesis.85,86 Moreover, Fountoulakis et al. found that this medication was effective in the long-term management of severe symptoms in two cases of DG refractory to treatment with first-line medications.87 Currently, the efficacy of a 4-week regimen of tradipitant, another NK-1 receptor antagonist, is being investigated to manage gastroparesis.

This review provides an updated overview of the currently used medications and their therapeutic effects on patients with gastroparesis secondary to diabetes in RCTs. Other systematic reviews have summarised pharmacological and other management approaches to DG, such as nutritional support, glycaemic management, surgical techniques, intrapyloric botulinum toxin injection and gastric electrical stimulation.

However, the current review was subject to some limitations. The impact of antiemetics was not assessed due to a lack of relevant RCTs. Furthermore, the design of included RCTs might have impacted the results. For example, there were conflicting outcomes between phase 2a and phase 2b studies of TZP-102 which included variations in breath test methods (a 6-hour 13C-octanoate test and a 3-hour 13C-Spirulina platensis test, respectively).32,43 Therefore, unified guidelines should be implemented and carefully employed for future trials. The FDA has provided several recommendations regarding this aspect, which include conducting double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with a 2-week screening period, a 12-week treatment period and an at least 2-week withdrawal period.88 RCTs of longer durations should be performed for at least 12 months. Importantly, patients with diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis should be studied in separate trials. Finally, efficacy assessment should primarily be based on the signs and symptoms of gastroparesis.

Conclusion

There is a significant unmet need for patients with DG who require effective medications to manage their symptoms with optimal levels of safety. Patients with mild to moderate symptoms are traditionally managed with metoclopramide or domperidone taking into consideration their cardiovascular consequences. In an endeavour to develop novel drugs, relamorelin, camicinal and prucalopride have shown the best outcomes; however, further investigations are required prior to approval for use in a healthcare setting. Future trials should be conducted based on unified guidelines such as those implemented by the FDA in order to enable comprehensive and reliable assessment of their outcomes.

References

- 1.Kempler P, Várkonyi T, Körei AE, Horváth VJ. Gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: The unattended borderline between diabetology and gastroenterology. Diabetologia. 2016;59:401–3. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3826-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Izbéki F, Rosztóczy A, Várkonyi T, Wittmann T. The clinical picture, diagnosis and therapy of gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy. In: Kempler P, Várkonyi T, editors. Neuropathies. A global clinical guide. Budapest, Hungary: Zafír Press-Mona Lib Kft; 2012. pp. 131–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boas I. 9th ed. [Diseases of the Stomach]. Leipzig, Germany: Georg Thieme; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kassander P. Asymptomatic gastric retention in diabetics (gastroparesis diabeticorum) Ann Intern Med. 1958;48:797–812. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-48-4-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnasamy S, Abell TL. Diabetic Gastroparesis: Principles and current trends in management. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:1–42. doi: 10.1007/s13300-018-0454-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacy BE, Crowell MD, Mathis C, Bauer D, Heinberg LJ. Gastroparesis: Quality of life and health care utilization. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52:20–4. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aleppo G, Calhoun P, Foster NC, Maahs DM, Shah VN, Miller KM, et al. Reported gastroparesis in adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D) from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:1669–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jdicomp.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bharucha AE. Epidemiology and natural history of gastroparesis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2015;44:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alipour Z, Khatib F, Tabib SM, Javadi H, Jafari E, Aghaghazvini L, et al. Assessment of the prevalence of diabetic gastroparesis and validation of gastric emptying scintigraphy for diagnosis. Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther. 2017;26:17–23. doi: 10.4274/mirt.61587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almogbel RA, Alhussan FA, Alnasser SA, Algeffari MA. Prevalence and risk factors of gastroparesis-related symptoms among patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2016;10:397–404. doi: 10.12816/0048734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horowitz M, Harding PE, Maddox AF, Wishart JM, Akkermans LM, Chatterton BE, et al. Gastric and oesophageal emptying in patients with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1989;32:151–9. doi: 10.1007/bf00265086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bytzer P, Talley NJ, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Horowitz M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with diabetes mellitus: A population-based survey of 15,000 adults. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1989–96. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, Talley NJ, et al. Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI): Development and validation of a patient reported assessment of severity of gastroparesis symptoms. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:833–44. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021689.86296.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, Hasler WL, Lin HC, Maurer AH, et al. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: A joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:753–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farmer AD, Scott SM, Hobson AR. Gastrointestinal motility revisited: The wireless motility capsule. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:413–21. doi: 10.1177/2050640613510161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumitrascu DL, Weinbeck M. Domperidone versus metoclopramide in the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:316–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heer M, Müller-Duysing W, Benes I, Weitzel M, Pirovino M, Altorfer J, et al. Diabetic gastroparesis: Treatment with domperidone--a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Digestion. 1983;27:214–17. doi: 10.1159/000198955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards RD, Valenzuela GA, Davenport KG, Fisher KL, McCallum RW. Objective and subjective results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial using cisapride to treat gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:811–16. doi: 10.1007/bf01295905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCallum RW, Cynshi O Investigative Team. Clinical trial: Effect of mitemcinal (a motilin agonist) on gastric emptying in patients with gastroparesis - a randomized, multicentre, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1121–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tack J, Rotondo A, Meulemans A, Thielemans L, Cools M. Randomized clinical trial: A controlled pilot trial of the 5-HT4 receptor agonist revexepride in patients with symptoms suggestive of gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:487–97. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stacher G, Schernthaner G, Francesconi M, Kopp HP, Bergmann H, Stacher-Janotta G, et al. Cisapride versus placebo for 8 weeks on glycemic control and gastric emptying in insulin-dependent diabetes: A double blind cross-over trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2357–62. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.7.5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wo JM, Ejskjaer N, Hellström PM, Malik RA, Pezzullo JC, Shaughnessy L, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Ghrelin agonist TZP-101 relieves gastroparesis associated with severe nausea and vomiting--randomised clinical study subset data. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:679–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franzese A, Borrelli O, Corrado G, Rea P, Di Nardo G, Grandinetti AL, et al. Domperidone is more effective than cisapride in children with diabetic gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:951–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erbas T, Varoglu E, Erbas B, Tastekin G, Akalin S. Comparison of metoclopramide and erythromycin in the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:1511–14. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.11.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray CD, Martin NM, Patterson M, Taylor SA, Ghatei MA, Kamm MA, et al. Ghrelin enhances gastric emptying in diabetic gastroparesis: A double blind, placebo controlled, crossover study. Gut. 2005;54:1693–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.069088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ejskjaer N, Vestergaard ET, Hellström PM, Gormsen LC, Madsbad S, Madsen JL, et al. Ghrelin receptor agonist (TZP-101) accelerates gastric emptying in adults with diabetes and symptomatic gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:1179–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ejskjaer N, Dimcevski G, Wo J, Hellström PM, Gormsen LC, Sarosiek I, et al. Safety and efficacy of ghrelin agonist TZP-101 in relieving symptoms in patients with diabetic gastroparesis: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:1069–e281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braden B, Enghofer M, Schaub M, Usadel KH, Caspary WF, Lembcke B. Long-term cisapride treatment improves diabetic gastroparesis but not glycaemic control. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1341–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehmann R, Honegger RA, Feinle C, Fried M, Spinas GA, Schwizer W. Glucose control is not improved by accelerating gastric emptying in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and gastroparesis. A pilot study with cisapride as a model drug. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2003;111:255–61. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ejskjaer N, Wo JM, Esfandyari T, Mazen Jamal M, Dimcevski G, Tarnow L, et al. A phase 2a, randomized, double-blind 28-day study of TZP-102 a ghrelin receptor agonist for diabetic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:e140–50. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkman HP, Carlson MR, Gonyer D. Metoclopramide nasal spray is effective in symptoms of gastroparesis in diabetics compared to conventional oral tablet. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:521–8. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snape WJ, Jr, Battle WM, Schwartz SS, Braunstein SN, Goldstein HA, Alavi A. Metoclopramide to treat gastroparesis due to diabetes mellitus: A double-blind, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:444–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-4-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCallum RW, Ricci DA, Rakatansky H, Behar J, Rhodes JB, Salen G, et al. A multicenter placebo-controlled clinical trial of oral metoclopramide in diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:463–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.6.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricci DA, Saltzman MB, Meyer C, Callachan C, McCallum RW. Effect of metoclopramide in diabetic gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:25–32. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patterson D, Abell T, Rothstein R, Koch K, Barnett J. A double-blind multicenter comparison of domperidone and metoclopramide in the treatment of diabetic patients with symptoms of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1230–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin A, Camilleri M, Busciglio I, Burton D, Smith SA, Vella A, et al. The ghrelin agonist RM-131 accelerates gastric emptying of solids and reduces symptoms in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1453–9.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hellström PM, Tack J, Johnson LV, Hacquoil K, Barton ME, Richards DB, et al. The pharmacodynamics, safety and pharmacokinetics of single doses of the motilin agonist, camicinal, in type 1 diabetes mellitus with slow gastric emptying. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:1768–77. doi: 10.1111/bph.13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin A, Camilleri M, Busciglio I, Burton D, Stoner E, Noonan P, et al. Randomized controlled phase Ib study of ghrelin agonist, RM-131, in type 2 diabetic women with delayed gastric emptying: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:41–8. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lembo A, Camilleri M, McCallum R, Sastre R, Breton C, Spence S, et al. Relamorelin reduces vomiting frequency and severity and accelerates gastric emptying in adults with diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:87–96.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Camilleri M, McCallum RW, Tack J, Spence SC, Gottesdiener K, Fiedorek FT. Efficacy and safety of relamorelin in diabetics with symptoms of gastroparesis: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:1240–50.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCallum RW, Lembo A, Esfandyari T, Bhandari BR, Ejskjaer N, Cosentino C, et al. Phase 2b, randomized, double-blind 12-week studies of TZP-102, a ghrelin receptor agonist for diabetic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:e705–17. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parkman HP, Carlson MR, Gonyer D. Metoclopramide nasal spray reduces symptoms of gastroparesis in women, but not men, with diabetes: Results of a phase 2B randomized study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1256–63.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silvers D, Kipnes M, Broadstone V, Patterson D, Quigley EM, McCallum R, et al. Domperidone in the management of symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis: efficacy, tolerability, and quality-of-life outcomes in a multicenter controlled trial. DOM-USA-5 Study Group. Clin Ther. 1998;20:438–53. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCallum RW, Cynshi OUS Investigative Team Efficacy of mitemcinal, a motilin agonist, on gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with symptoms suggesting diabetic gastropathy: A randomized, multi-center, placebo-controlled trial Aliment Pharmacol Ther 200726107–16. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanger GJ, Furness JB. Ghrelin and motilin receptors as drug targets for gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lata PF, Pigarelli DL. Chronic metoclopramide therapy for diabetic gastroparesis. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:122–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solmi M, Pigato G, Kane JM, Correll CU. Clinical risk factors for the development of tardive dyskinesia. J Neurol Sci. 2018;389:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Camilleri M. Novel diet, drugs, and gastric interventions for gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1072–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koch KL, Stern RM, Stewart WR, Vasey MW. Gastric emptying and gastric myoelectrical activity in patients with diabetic gastroparesis: Effect of long-term domperidone treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1069–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silvers D, Kipnes M, Broadstone V, Patterson D, Quigley EM, McCallum R, et al. Domperidone in the management of symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis: Efficacy, tolerability, and quality-of-life outcomes in a multicenter controlled trial. DOM-USA-5 Study Group. Clin Ther. 1998;20:438–53. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soykan I, Sarosiek I, McCallum RW. The effect of chronic oral domperidone therapy on gastrointestinal symptoms, gastric emptying, and quality of life in patients with gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:976–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris AD, Chen J, Lau E, Poh J. Domperidone-associated QT interval prolongation in non-oncologic pediatric patients: A review of the literature. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2016;69:224–30. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v69i3.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L American College of Gastroenterology. Clinical guideline: Management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18–37. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mosińska P, Zatorski H, Storr M, Fichna J. Future treatment of constipation-associated disorders: Role of relamorelin and other ghrelin receptor agonists. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:171–9. doi: 10.5056/jnm16183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frazee LA, Mauro LS. Erythromycin in the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Am J Ther. 1994;1:287–95. doi: 10.1097/00045391-199412000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richards RD, Davenport K, McCallum RW. The treatment of idiopathic and diabetic gastroparesis with acute intravenous and chronic oral erythromycin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:203–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Desautels SG, Hutson WR, Christian PE, Moore JG, Datz FL. Gastric emptying response to variable oral erythromycin dosing in diabetic gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:141–6. doi: 10.1007/bf02063957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berne JD, Norwood SH, McAuley CE, Vallina VL, Villareal D, Weston J, et al. Erythromycin reduces delayed gastric emptying in critically ill trauma patients: A randomized, controlled trial. J Trauma. 2002;53:422–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Albert RK, Schuller JLCOPD Clinical Research Network Macrolide antibiotics and the risk of cardiac arrhythmias Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20141891173–80. 10.1164/rccm.201402-0385CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Akiyoshi T, Ito M, Murase S, Miyazaki M, Guengerich FP, Nakamura K, et al. Mechanism-based inhibition profiles of erythromycin and clarithromycin with cytochrome P450 3A4 genetic variants. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2013;28:411–15. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-12-RG-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewis K, Alqahtani Z, McIntyre L, Almenawer S, Alshamsi F, Rhodes A, et al. The efficacy and safety of prokinetic agents in critically ill patients receiving enteral nutrition: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2016;20:259. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1441-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Loughlin J, Quinn S, Rivero E, Wong J, Huang J, Kralstein J, et al. Tegaserod and the risk of cardiovascular ischemic events: An observational cohort study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2010;15:151–7. doi: 10.1177/1074248409360357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hobson R, Farmer AD, Dewit OE, O’Donnell M, Hacquoil K, Robertson D, et al. The effects of camicinal, a novel motilin agonist, on gastro-esophageal function in healthy humans-a randomized placebo controlled trial. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1629–37. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barton ME, Otiker T, Johnson LV, Robertson DC, Dobbins RL, Parkman HP, et al. 70 A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study (MOT114479) to evaluate the safety and efficacy and dose response of 28 days of orally administered camicinal, a motilin receptor agonist, in diabetics with gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(S):20. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carbone F, Rotondo A, Andrews CN, Holvoet L, Van Oudenhove L, Vanuytsel T, et al. 1077 A controlled cross-over trial shows benefit of prucalopride for symptom control and gastric emptying enhancement in idiopathic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:S213–4. [Google Scholar]

- 68.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. How to Request Domperidone for Expanded Access Use. [Accessed: Jul 2019]. From: www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/howdrugsaredevelopedandapproved/approvalapplications/investigationalnewdrugindapplication/ucm368736.htm.

- 69.Kumar M, Chapman A, Javed S, Alam U, Malik RA, Azmi S. The investigation and treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Ther. 2018;40:850–61. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nelson AD, Camilleri M, Acosta A, Busciglio I, Linker Nord S, Boldingh A, et al. Effects of ghrelin receptor agonist, relamorelin, on gastric motor functions and satiation in healthy volunteers. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1705–13. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deloose E, Depoortere I, de Hoon J, Van Hecken A, Dewit OE, Vasist Johnson LS, et al. Manometric evaluation of the motilin receptor agonist camicinal (GSK962040) in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30:e13173. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sajid MS, Hebbar M, Baig MK, Li A, Philipose Z. Use of prucalopride for chronic constipation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized, controlled trials. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:412–22. doi: 10.5056/jnm16004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phillips LK, Deane AM, Jones KL, Rayner CK, Horowitz M. Gastric emptying and glycaemia in health and diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:112–28. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marathe CS, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Relationships between gastric emptying, postprandial glycemia, and incretin hormones. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1396–405. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Halland M, Bharucha AE. Relationship between control of glycemia and gastric emptying disturbances in diabetes mellitus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:929–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1990;33:675–80. doi: 10.1007/bf00400569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Homko CJ, Duffy F, Friedenberg FK, Boden G, Parkman HP. Effect of dietary fat and food consistency on gastroparesis symptoms in patients with gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:501–8. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Olausson EA, Störsrud S, Grundin H, Isaksson M, Attvall S, Simrén M. A small particle size diet reduces upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with diabetic gastroparesis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:375–85. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Parkman HP, Yamada G, Van Natta ML, Yates K, Hasler WL, Sarosiek I, et al. Ethnic, racial, and sex differences in etiology, symptoms, treatment, and symptom outcomes of patients with gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1489–99.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Parkman HP, Hallinan EK, Hasler WL, Farrugia G, Koch KL, Calles J, et al. Nausea and vomiting in gastroparesis: Similarities and differences in idiopathic and diabetic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1902–14. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Friedenberg FK, Kowalczyk M, Parkman HP. The influence of race on symptom severity and quality of life in gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:757–61. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182819aae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barrett TW, DiPersio DM, Jenkins CA, Jack M, McCoin NS, Storrow AB, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of ondansetron, metoclopramide, and promethazine in adults. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:247–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Badowski ME. A review of oral cannabinoids and medical marijuana for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A focus on pharmacokinetic variability and pharmacodynamics. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2017;80:441–9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-017-3387-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Richards JR, Gordon BK, Danielson AR, Moulin AK. Pharmacologic treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37:725–34. doi: 10.1002/phar.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang Y, Yang Y, Zhang Z, Fang W, Kang S, Luo Y, et al. Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist-based triple regimens in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A network meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pasricha PJ, Yates KP, Sarosiek I, McCallum RW, Abell TL, Koch KL, et al. Aprepitant has mixed effects on nausea and reduces other symptoms in patients with gastroparesis and related disorders. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:65–76.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fountoulakis N, Dunn J, Thomas S, Karalliedde J. Successful management of refractory diabetic gastroparesis with long-term Aprepitant treatment. Diabet Med. 2017;34:1483–6. doi: 10.1111/dme.13413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.US Food & Drug Administration. Gastroparesis: Clinical evaluation of drugs for treatment. [Accessed: Jul 2019]. From: www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm455645.pdf.