ABSTRACT

Objectives: Health-care professionals (HCPs) are at very high risk for accidental exposure to hepatitis B virus (HBV) from infected patients; as such, this study aimed to investigate the knowledge, awareness, attitude, and practice of HCPs toward hepatitis B vaccination.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study with a pre-tested, validated questionnaire in seven major cities in Saudi Arabia from January to April 2015. The questionnaire consisted of four sections: demographics, knowledge, awareness of hepatitis B infection, and attitude of HCPs toward HBV. We analyzed the data collected from study participants using SAS® V9.2.

Results: Approximately 16.5% of participants reported that they had not received the hepatitis B vaccine; however, the majority of participants believed that hepatitis B is common (73.2%) and that vaccination is an effective strategy to reduce disease incidence (75%). Availability of the vaccine was a major barrier to vaccination (48.7%), together with safety concerns surrounding the vaccine (37%).

Approximately 31.2% of non-vaccinated participants believed the hepatitis B vaccine is not safe, while only 8% possessed this belief in the vaccinated group. Additionally, 36.4% of non-vaccinated participants were unsure of the effectiveness of the vaccine, compared to 24.3% in the vaccinated group. Inability to afford the vaccine was reported by 18.2% of the non-vaccinated group compared to only 4% of vaccinated participants.

Conclusion: There is notable hepatitis B vaccination coverage among HCPs, but observed levels are below global standards. We believe the hurdles preventing non-vaccinated HCPs from being immunized must be addressed.

KEYWORDS: Attitude and knowledge, healthcare professionals, Hepatitis B vaccine, Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

Hepatitis B is a serious hepatic infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Hepatitis B is a chronic and alarming public health problem worldwide, leading to cirrhosis, liver cancer and liver failure if left untreated.1 HBV imposes a significant burden on health-care systems due to its high morbidity, mortality, and treatment costs. Approximately 15–40% of infected individuals develop cirrhosis, liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma.2 Globally, approximately 400 million people suffer from hepatitis, with an approximate increase of 1 million cases and it claims an estimated 1.45 million lives each year.3,4 Furthermore, approximately 257 million people are chronically infected with HBV, the majority of whom are unaware they are infected, leading to the infection of others and, ultimately, death due to liver disease.5

Hepatitis B is a contagious viral disease that is transmitted through sexual contact or sharing contaminated syringes, needles or other injectable equipment or from mother to baby at birth.6 .Blood and serous exudates contain higher concentrations of HBV. Interferon-alpha (IFN-α) is used for the treatment of chronic HBV infections but has limited efficacy in patients with certain characteristics such as childhood infection, decompensated liver disease, and immunosuppressed.7 In addition, several therapeutics were unsuccessfully trialed as potential anti-HBV treatment including ribavirin,8 which has a broad-spectrum antiviral activity.9 Thus far, chronic HBV remains an untreatable infection.4

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Asians, including Arabs in the Arabian Peninsula, are disproportionately affected by chronic hepatitis B infection and its sequelae, which include cirrhosis, liver cancer, and liver failure. Screening programs in the United States estimate that 10–15% of health-care professionals (HCPs) are chronically infected with HBV, compared to only 0.5% of the general population.10,11 HCPs are constantly exposed to percutaneous injuries that have been estimated to result in over 60,000 HBV infections annually.12

Safe and effective hepatitis B vaccines have been available since the 1980s and prevent acute and chronic infections with an estimated effectiveness of 95%.13 Vaccines are preventive preparations against hepatitis B and are available for people of all age groups. A recent follow-up study reported that the vaccine is able to protect an immunized individual even 30 years later, suggesting high vaccine efficacy.14 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends vaccination of newborns worldwide as well as those individuals with risk factors for acquiring hepatitis B, such as injecting drug users, HCPs and those with multiple sex partners. Universal vaccination and selective vaccination are two main programs through which the vaccine is administered to the needy. In 1992, the WHO recommended universal vaccination against hepatitis B in newborns, and many countries worldwide have adopted this measure.15

According to the advisory committee on immunization and practices (ACIP) in the US, vaccination is the most effective measure to prevent HBV infection and its consequences.16 The Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia also follows the ACIP recommendations for adults and children. However, proper knowledge, supportive attitudes, and practices toward hepatitis B and its prevention are the basis for preventing its spread.17 Major challenges related to the prevention of hepatitis B include lack of proper preventive policies in hospitals or health-care institutions, low perception of hepatitis B risk and inadequate orientation of newly recruited HCPs.18 Studies have shown that increased knowledge of hepatitis B is noticeably associated with hepatitis B vaccination.19 Thus, this study was performed with the objective of assessing HCP knowledge, awareness, attitudes and practice of HCPs in Saudi Arabia towards hepatitis B vaccination.

A community-based epidemiological study that investigated HBV prevalence in Saudi children during the 1980s, before the introduction of the vaccine program, was shown to be at 7%.20 In 1989, the Saudi government introduced a mandatory HBV vaccine program that resulted in a significant reduction in HBV prevalence. A study by Al-Faleh that investigated the long-term protection of hepatitis B vaccine after almost two decades after the program introduction reported 0% HBV endemicity among students aged 16–18 years, from different endemic areas across the country.21 However, Saudi Arabia has a large number of HCPs scattered throughout the kingdom including foreign expatriates who come from different parts of the world some of whom come from high HBV prevalent countries. Thus, this study was performed with the objective of assessing HCP knowledge, awareness, attitudes and practice of HCPs in Saudi Arabia toward hepatitis B vaccination.

2. Results

Five hundred questionnaires were randomly distributed among HCPs. Of those, 476 questionnaires were returned for a response rate of 95.2%. As shown in Table 1, approximately 46% of the HCPs were below the age of 30, and 65% were female. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of HCPs who participated in this study were nurses, followed by physicians (16%), pharmacists (9%) and others (12%). Approximately two-thirds (65%) of HCPs possessed a minimum of a bachelor’s degree in their respective fields. A major fraction (47%) of HCPs had less than five years of professional experience.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of all participating HCPs.

| Characteristics | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <30 | 45.9 |

| 30–50 | 50.1 |

| >50 | 4.0 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 34.7 |

| Female | 65.3 |

| Profession | |

| Physician | 16.1 |

| Pharmacist | 8.8 |

| Nurse | 62.7 |

| Lab technician | 7.5 |

| Radiologist | 0.2 |

| Dentist | 1.9 |

| Technician | 2.8 |

| Education | |

| Diploma | 22.8 |

| Bachelor | 65.2 |

| Higher education or training | 11.9 |

| Experience | |

| <5 yrs | 46.7 |

| 10–15 yrs | 33.0 |

| >15 yrs | 10.3 |

| Vaccinated against hepatitis B (All required doses) | |

| Yes | 83.5 |

| No | 16.5 |

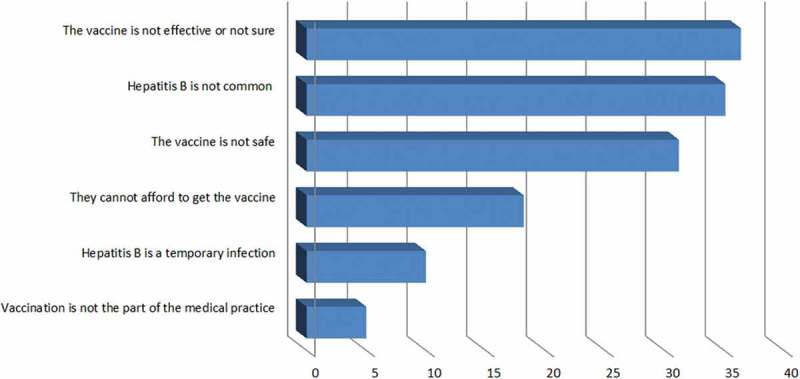

A quite significant number of HCPs (16.5%) had not received the hepatitis B vaccine (Table 1). Of those who were vaccinated (i.e., the full 3 doses), the percentages of vaccination among physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other HCPs were 79%, 86.5%, 67.5%, and 71.4%, respectively. Percent vaccination was dependent on the type of profession (p < .01). In addition, for 84% of the vaccinated HCPs, there are standard procedures and protocols in their centers/hospitals to vaccinate the new-employed staff (p < .001). Furthermore, around 67% of the vaccinated HCPs have a standing order for hepatitis B vaccine in their centers/hospitals (p < .001). Despite the fact they had been vaccinated, 13% of these HCPs did not believe that the vaccine prevents the infection. On the other hand, around 87% of the vaccinated HCPs believe the vaccine is safe. Only 44% of the vaccinated HCPs are aware of CDC/ACIP guidelines (p < .001). HCPs who were not vaccinated provided several reasons for not doing so: some HCPs who were not vaccinated believed that the vaccine does not work for everyone (36.4%), believed that hepatitis B infection is not common (35.1%) feared that the vaccine is not safe (31.2%) (Figure 1). Additional reasons for noncompliance included the inability to afford the vaccine (18.2%), the misbelief that HBV infection is temporary (10%) and the idea that vaccination is not part of medical practice (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reasons for non-compliance with vaccination recommendations among non-immunized HCPs.

We also assessed knowledge of the hepatitis B vaccine in the questionnaire (Table 2). Approximately 73.7% of HCPs believed that vaccination is the most effective way to prevent hepatitis B infection, a result that explains the high percentage of HCPs who were vaccinated against HBV. More than one-half (52%) of HCPs thought that hepatitis B is the most common type of hepatitis in Saudi Arabia. Approximately 80.1% of HCPs indicated that the liver is the organ most commonly affected by HBV. HCPs believed that infection is spread through the blood (93.7%), needle sharing (76%), mother to child (60.9%) and saliva (34%). A large number of respondents believed that both HCPs and children should be vaccinated (85.7% and 68.5%, respectively). However, only 61% agreed that vaccines could be administered to newborn babies (Table 2).

Table 2.

HCP knowledge about hepatitis B disease and its vaccine.

| Questions | Percentage |

|---|---|

| • Knowledge about hepatitis B disease Which type of hepatitis is more common among the Saudi population? |

9.3 |

| Hepatitis A | |

| Hepatitis B | 52.8 |

| Hepatitis C | 19.4 |

| Hepatitis D | 1.1 |

| Hepatitis E | 17.3 |

| Hepatitis B is not common. | |

| Correct | 19.7 |

| Incorrect | 73.2 |

| Not sure | 7.1 |

| Which body part is most affected by hepatitis B infection? | 0.9 |

| Brain | |

| Blood | 17.5 |

| Liver | 80.1 |

| Kidney | 1.5 |

| Hepatitis B is a temporary infection. | |

| Correct | 11.1 |

| Incorrect | 81.3 |

| Not sure | 7.6 |

| Hepatitis B virus is transmitted through. | 8.8 |

| Physical contact | |

| Saliva | 34 |

| Blood | 93.7 |

| From infected mother to child | 60.9 |

| Airborne droplet | 8.4 |

| Needle sharing | 76 |

| Hepatitis B-infected people can spread the infection even when they are feeling well. | 72.1 |

| Correct | |

| Incorrect | 18.2 |

| Not sure | 9.7 |

| People with hepatitis B can transmit the infection only after their symptoms appear. | |

| Correct | 9.6 |

| Incorrect | 79.4 |

| Not sure | 11.0 |

| Healthcare professionals are less susceptible to hepatitis B infections than other people. | |

| Correct | 14.7 |

| Incorrect | 80.9 |

| Not sure | 4.4 |

| • Knowledge about hepatitis B Vaccine Do you think the hepatitis vaccine is effective in preventing hepatitis B infection? |

|

| Yes | 73.7 |

| No | 15.2 |

| I don’t know | 11.1 |

| Do you think administering the hepatitis B vaccine should be part of your medical practice? | |

| Yes | 88.3 |

| No | 6 |

| I don’t know | 5.7 |

| Which of the following groups should receive the hepatitis B vaccine? | |

| Children | 68.5 |

| Elderly | 35.5 |

| Healthcare professionals | 85.7 |

| Pregnant women | 31.3 |

| Which of the following groups should not receive the hepatitis B vaccine? | |

| Pregnant women | 53.4 |

| Immunocompromised | 55.3 |

| People with acute disease | 38.2 |

| Diabetics | 7.8 |

| People allergic to the HBV vaccine | 65.6 |

| People with chronic kidney disease | 15.8 |

| The hepatitis B vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine. | |

| Correct | 59.3 |

| Incorrect | 27.8 |

| Not sure | 12.9 |

| The hepatitis B vaccine may cause some people to get hepatitis B infection. | |

| Correct | 23.7 |

| Incorrect | 62 |

| Not sure | 14.3 |

| Hepatitis B vaccination does not work for everyone. | |

| Correct | 36.7 |

| Incorrect | 44.8 |

| Not sure | 18.5 |

| You can get hepatitis B vaccine more than once. | |

| Correct | 38.2 |

| Incorrect | 48.9 |

| Not sure | 12.9 |

| The hepatitis B vaccine should not be given to newborn babies. | |

| Correct | 25.6 |

| Incorrect | 60.9 |

| Not sure | 13.5 |

HCP knowledge with respect to population groups who should not receive the vaccine was as follows: people allergic to hepatitis B vaccine (65.6%), pregnant women (53.4%), immunocompromised patients (55.3%), and people with acute disease (38.2%) (Table 2). Around (80.9%) of HCPs agreed that health-care professionals are more susceptible to infection than are other people. Seventy-two percent said that hepatitis B could be spread by infected people even when they are feeling well. Approximately 81.3% of HCPs agreed that hepatitis B infection is not temporary, and 79.4% believed that HBV can be transmitted to others before symptoms appear in infected people. Nearly all (88.3%) HCPs believed vaccination should be part of their medical practice. Seventy-three percent said that hepatitis B is a common infection. Fifty-nine percent of HCPs thought the hepatitis B vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine that should not be given to newborn babies (25.6%) due to the chance of infection. Surprisingly, only 62% of HCPs believed that the vaccine cannot cause infection, and only 44.8% thought that the vaccine works for everyone. Only 48.9% of HCPs agreed that hepatitis B does not infect a person more than once.

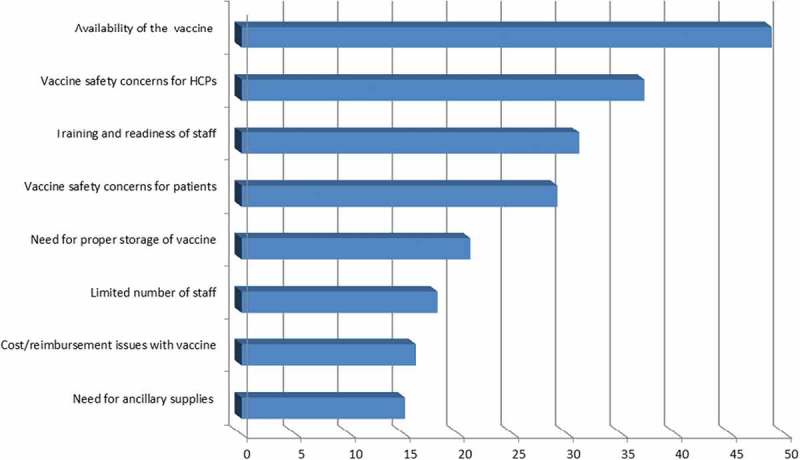

Next, we assessed awareness of vaccination programs among HCPs. Greater than 57% were not aware of the CDC or ACIP guidelines for vaccination (Table 3). Approximately 79% of participants agreed that their hospitals have standard procedures and protocols to vaccinate new staff members, and 71.3% indicated that it was required from them to be vaccinated before they could perform their professional duties. Fifty-three percent said that their health centers provide hepatitis B vaccine for the public. However, vaccine availability and the safety concerns of HCPs towards the vaccine were the main barriers to provide the vaccine to the public (48.7% and 37%, respectively) (Figure 2).

Table 3.

HCP awareness about hepatitis B vaccine.

| Variables | Yes (%) | No (%) | Don’t know (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are you aware of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) or Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) guidelines for hepatitis B vaccination? | 42.7 | 57.3 | - |

| Does your hospital have standard procedures and protocols to vaccinate new staff members? | 78.8 | 12.2 | 9 |

| In your hospital, are you required to have hepatitis B vaccination before you can start working? | 71.3 | 23.2 | 5.5 |

| Does your practice/center offer the hepatitis B vaccine to patients? | 53.4 | 18.4 | 28.2 |

| Does your practice/center have standing orders regarding the hepatitis B vaccine? | 63.9 | 12.8 | 23.4 |

Figure 2.

Barriers to providing hepatitis B vaccine to the public according to the instituations of HCPs.

Furthermore, our results indicated that 55.9% of HCPs agreed that hospital personnel are at high risk for HBV infection (Table 4). Importantly, 34% of them mentioned that they are always in contact with patients or patient samples, and 33.6% admitted to having experienced a needle stick injury (Table 4). The potential impact of hepatitis B infection for HCPs was considered very serious by 53.6% of participants, and 26.5% attended training in the last 12 months (Table 4).

Table 4.

Attitude of HCPs towards hepatitis B disease and its vaccine.

| Questions | Percentage |

|---|---|

|

Towards Hepatitis B Disease Do you have direct contact with patients or patient samples? |

|

| Always | 34 |

| Usually | 15.1 |

| Sometimes | 31.3 |

| Rarely | 12 |

| Never | 7.6 |

| Is hospital staff at high risk for infectious exposure? | |

| Very high risk | 55.9 |

| Somewhat risk | 28.4 |

| Low risk | 11.8 |

| No risk | 1.5 |

| Not sure | 2.4 |

| Potential seriousness of hepatitis B infection for yourself is considered: | |

| Very serious | 53.6 |

| Serious | 26.5 |

| Minor | 10.5 |

| Not serious | 4.8 |

| Not sure | 4.6 |

|

Towards Hepatitis B Vaccine Have you or your colleagues participated in any training or continuing education related to the hepatitis B vaccine in the past 12 months? | |

| Yes | 26.5 |

| No | 60.8 |

| I don’t know | 12.7 |

The results of the multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that female gender (odds ratio (OR) = 2.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.02–4.04), the presences of standard procedures and protocols to vaccinate new staff members in health centers (OR = 3.30, 95% CI = 1.21–9.00), the presence of standing orders regarding Hepatitis B vaccine in health centers (OR = 4.83, 95% CI = 2.00–12.39), and the awareness of the CDC/ACIP* guidelines for Hepatitis B vaccination among health workers (OR = 2.80, 95% CI = 1.13–6.94) were the predictors for HCPs’ acceptance to Hepatitis B vaccination (Table 5).

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis identifying predictors for receiving the hepatitis B vaccine among the participating healthcare professionals.

| Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | |

|---|---|---|

|

Gender Male (reference) |

- | - |

| Female | 2.03 | 1.02–4.04 |

|

There are standard procedures and protocols to vaccinate new staff members No (reference) |

- | - |

| Yes | 3.30 | 1.21–9.00 |

| I don’t know | 0.76 | 0.21–2.76 |

|

HCPs are required to have hepatitis B vaccination before they can start working No (reference) |

- | - |

| Yes | 1.51 | 0.63–3.65 |

| I don’t know | 2.46 | 0.37–16.15 |

|

There are standing orders regarding Hepatitis B vaccine No (reference) |

- | - |

| Yes | 4.83 | 1.20–12.39 |

| I don’t know | 1.52 | 0.58–3.96 |

|

Did HCPs participate in any training or continuing education related to Hepatitis B vaccine in the past 12 months? No (reference) |

- | - |

| Yes | 0.57 | 0.23–1.38 |

| I don’t know | 1.11 | 0.36–3.40 |

|

HBV vaccine is very effective in preventing hepatitis B infection No (reference) |

- | - |

| Yes | 0.74 | 0.28–2.22 |

| I don’t know | 0.37 | 0.10–1.51 |

|

Awareness of CDC/ACIP guidelines No (reference) |

- | |

| Yes | 2.80 | 1.13–6.94 |

| I don’t know | 0.05 | 0.01–0.79 |

3. Discussion

There is no cure for individuals with chronic HBV infections and that chronic infections are associated with cirrhotic liver failure, and infected individuals have an increased risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma.4 HCPs are among the population groups that are highly exposed to HBV-infected patients or patient samples, tremendously increasing their risk for accidentally acquiring the infection. HCPs interact with HBV-infected patients to provide different health services, whether they know if these patients are aware of their infection or not, as it is ethically required for HCPs to provide health services to HBV-infected patients. Fortunately, an effective measure to protect HCPs from infection is available via the HBV vaccine. Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the knowledge and attitude of HCPs toward hepatitis B vaccination in different regions of Saudi Arabia. This type of study is likely the first conducted among HCPs in different regions of Saudi Arabia.

Several studies around the world have shown that vaccination prevents hepatitis B infection, and HCP vaccination has proven beneficial in preventing the spread of the disease and improving the health status of HCPs.22 The results of our current study indicate a good percentage of HCPs (83.5%) are vaccinated against HBV. However, this is still less than the 2020 target of the CDC in the USA, which has a vaccine coverage goal of more than 90%.23 Similar results were obtained in a study conducted among dentists in Saudi Arabia, of which 80.5% were vaccinated.24 Thus, the current findings show that there is still a need to improve vaccine coverage in different regions of Saudi Arabia to ensure only minimal chances of HBV infection among health-care professionals and patients.

We only studied the general vaccination rate and knowledge of HCPs from wide geographic areas, however, studying the differences between these areas and the workers themselves (locals vs. foreigners) are warranted but were out of the scope of the current study. While the differences between the areas for the local workers may not be significant, as they are expected to have gone through the same mandatory vaccination process requirements, it is, however, valid to be investigated for the foreign workers. This is due to the large number of foreign HCPs in Saudi hospitals and the difference in their distributions amongst these areas.

Studies to understand the knowledge of the hepatitis B vaccine have been conducted throughout the world, among both the general population and health-care workers and in developed as well as developing countries.25,26 The focus of these studies was to determine the extent of vaccination in the general population and health-care workers to assess the gap between protocol and regular practice. According to an Ethiopian study, poor knowledge of health-care workers, who are supposed to be well educated about the vaccination program, accounted for lower numbers of people vaccinated against hepatitis B.25 Although this study contained few participants, its results demonstrate positive meaning and correlation. In Sweden, where the hepatitis B vaccine is not included in the universal vaccination program, studies have been conducted to understand the knowledge of the vaccine in the general population and vaccination rates in health-care workers.26,27 The study reported that parent knowledge about the hepatitis vaccine is good in the educated population and that health-care workers are not reluctant to be vaccinated, but employers fail to vaccinate employees. Studies have also been conducted among dental students to understand their knowledge and to assess their vaccination status. One study conducted in India, a developing country, found that student knowledge of hepatitis B (80%+ responses) is good but is accompanied by poor vaccination rates (44.4%) and a poor attitude towards HBV vaccination.28

Overall, the percentage of vaccination is highest in nurses among all HCPs. Data revealed that HCP vaccination is dependent on the professional title (p < .01). Only 73.7% of HCPs surveyed thought that the vaccine is an effective means to prevent hepatitis B infection. Similarly, in a study conducted in the Al-Jouf province of Saudi Arabia, approximately 80% of HCPs responded that the vaccine is an effective method to prevent hepatitis B infection.29 In our study, approximately one-fourth (23.7%) of HCPs thought the vaccine may cause disease. This attitude of HCPs may negatively influence vaccination coverage. Other questions related to HCP knowledge of the hepatitis B vaccine also resulted in only 70–80% correct responses. Of note, 80.1% of HCPs stated that the liver is the organ most affected by hepatitis B infection, indicating the need to improve knowledge of HBV disease.

In the present study, 16.5% of HCPs were not vaccinated against HBV, and several reasons for noncompliance are provided in Figure 1. Clearly, poor knowledge and lack of understanding about the disease or the vaccine contributed to this finding. In addition, certain populations attributed their lack of vaccination to an inability to afford the vaccine (16%). In addition, and significantly, only 26.5% of total HCPs had attended a training program related to HBV in the last 12 months, resulting in inadequate knowledge of the hepatitis B vaccine among HCPs. A comparison between the vaccinated and the non-vaccinated groups revealed that 31.2% of the non-vaccinated group believed that the HBV vaccine is not safe, or were not sure about its safety, while only 8% had this belief in the vaccinated group. In addition, 36.4% of the non-vaccinated group thought that the vaccine was not effective, or were not sure about its effectiveness compared with 24.3% in the vaccinated group. Another misbelief is that 35.1% of the non-vaccinated group agreed that hepatitis B infection is not common in Saudi Arabia compared with 24.6% among the vaccinated group. Inability to afford the vaccine was reported by 18.2% of the non-vaccinated group compared with only 4% in the vaccinated group. However, the vaccine is provided free of charge for local HCPs; thus, those who selected the cost of the vaccine are more likely to be foreign HCPs. Hence, the need to improve knowledge of the disease and the vaccine is always present, together with ensuring that the Ministry of Health enforces hospital and health entities to provide the vaccine free of charge to their foreign HCPs to improve vaccination coverage and protection.

The participants’ beliefs of vaccine effectiveness, perceived disease susceptibility, and vaccine cost do not always affect the overall vaccination rate. This speculation is supported by findings from a similar study by Leung et al. that investigated the knowledge, attitudes, and practice among female university students in Hong Kong toward human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine.30 The study reported that vaccine cost, perceived disease susceptibility, and perceived vaccine effectiveness were not found to be associated with HPV vaccination rate. However, the study claimed awareness about the vaccine, the disease, and public acceptance is the main reason for increasing vaccination rate in their study.30

Awareness of current guidelines and standard hospital procedures regarding HBV remains poor compared with HCP knowledge of hepatitis B vaccination and vaccination rates. There is a need for more training sessions to explain current guidelines to HCPs to improve their awareness and understanding of hepatitis B vaccination. The attitude of hospital staff towards hepatitis B vaccination is not optimal, and training sessions might improve the overall sentiment. Other studies conducted in Saudi Arabia among medical students have found similar results to those obtained in this study for HCPs and concluded that training is a requisite for HCP knowledge improvement.29,31 The Saudi Ministry of Health has long been making every effort to overcome hepatitis and taking the necessary strategic actions against the disease, as evidently manifested in the development of a national, long-term immunization plan, in addition to a series of awareness campaigns. The results from our study also reiterate the need to support the efforts of the Ministry of Health, including improving HCP knowledge through training sessions.

4. Study strengths and limitations

The study has several strengths; it is the first study that assessed the coverage, knowledge, attitude, the practice of HBV vaccination in seven cities in different regions of Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, it covers all type of care which are primary, secondary and tertiary health care. Another strength of this study was the high response rate of 95.2% which is considered a good response rate for such study. Having this response rate along with conducting this study in several cities in Saudi Arabia might lead to the generalizability of the results. Nevertheless, this study has several limitations, since it is a retrospective study, it suffered from several types of biases such as recall and researcher biases; however, we tried to limit these biases. For instance, researcher bias was mitigated by having pre-validated data collection and this validated data collection was piloted to experts having both clinical and research background. Also, recall bias was mitigated by avoiding questions based on guessing and suggestion. Another possible bias was that we relied on HCPs honesty to self-report their vaccination status; these data, however, were not validated against other references such as employment record.

5. Conclusion

This is the first study to investigate the rate and knowledge of hepatitis B vaccination in multiple and major cities in Saudi Arabia. The overall vaccination rate of the investigated cities in this study is comparable to previously published reports. Although it appears that a substantial fraction of HCPs are vaccinated, the percentage does not meet the international accredited standard and must be improved through frequent training sessions on vaccination. This study can assist authorities in improving vaccine coverage because it sheds light on factors such as inaccurate beliefs that contribute to the lack of international coverage standards among HCPs. Additionally, barriers to vaccination, such as vaccine affordability for foreign workers, require attention. Thus, policymakers are encouraged to implement a requirement for hepatitis B vaccine for all HCPs to increase coverage and to possibly eradicate a vaccine preventative infection.

6. Materials and methods

6.1. Study design, location, and duration

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in governmental tertiary care hospitals, secondary centers, and primary care clinics in seven cities inside Saudi Arabia, specifically Riyadh, Al Qassim, Eastern region, Tabuk, Arar, Hail, and Mecca from the period of January to April 2015. These sites were randomly selected from a list of available governmental hospitals and health-care institutions. The surveys were collected from HCPs working in a total of five tertiary hospitals (one hospital from each of the studied cities except Tabuk and Mecca), four secondary care centers from Hail, Mecca, Tabuk, and Qassim, as well as seven primary care centers from each city. The research protocol was reviewed, and ethical approval was granted by the Medication Safety Research Chair, King Saud University. Each of the studied sites was provided with the study plan, questionnaire, and ethical approval before the beginning of survey distributions.

6.2. Study population

The study population comprised HCPs working in different health-care facilities in seven selected cities in Saudi Arabia. The questionnaire was administered in English, and every health-care center’s Administrative Chief was consulted for official permission to perform the study before enrolling the subjects. The lists of HCPs at different hospitals were provided by Administrative Chief from each participating center and we used a simple random sampling technique to select a sample from each hospital.

6.3. Instrument and instrumentation

The instrument used in this study was a questionnaire consisting of four major sections. The first section contained questions designed to gather demographic variables, including age groups, gender, profession, level of education, and years of experience. The second part of the questionnaire assessed knowledge of HBV infection, including methods of transmission, vaccination efficiency and need, and whether hepatitis B vaccination should be part of the medical practice. The third section measured HCP awareness about hepatitis B infection and vaccination. The last section measured HCP attitudes toward the HBV vaccine. The survey did not collect any identifiers to ensure confidentiality and to protect the participants’ privacy. The survey was piloted and pre-tested with 10 HCPs with both clinical and research backgrounds for validation, which resulted in minor modifications in the language.

Two pharmacists from the research team were involved in this study to distribute the questionnaire to HCPs at randomly selected private hospitals, polyclinics and government hospitals of Saudi Arabia. The selected samples included medical doctors, nurses, laboratory personals, health officers, and pharmacists. Cluster random sampling was used to divide each region into four sub-regions (clusters); at least one clinic or hospital from cluster A from each region was selected. Three days after distribution, we collected the completed questionnaires. Another attempt was made two days later to collect questionnaires that had not been completed during the first collection. The questionnaire was voluntary, and the completion and return of the questionnaire were taken as consent to participate. After the second attempt, HCPs who did not return the questionnaire were considered non-respondents.

6.4. Sample size calculation

To calculate the sample size of the study, the absolute error was estimated to be 5% and a 95% confidence level was used. In addition, a previous study was conducted under similar settings, which found that the influenza vaccination rate of HCPs was approximately 60%.32 Therefore, all the sample size calculated for this study using the aforementioned information was 368 participants. In addition, the attrition rate (i.e., to consider non-respondents) was 20%. Therefore, the required number of participants was 442.

6.5. Statistical analyses

We performed descriptive statistics to accurately interpret and present the results. Chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests were used to analyze categorical data to determine compliance with vaccination among different types of HCPs. To assess the predictors for getting vaccinated, a multivariate logistic regression model was built. The dependent variable was the vaccination status and it was dichotomous (i.e., vaccinated or unvaccinated). The relationship between the dependent variable (vaccination status) and the independent variables was determined by bivariate analysis such as the chi-square test or independent t-test. Those statistically significant independent variables were entered the final model to determine the predictors for the vaccination status. We conducted all statistical tests with a two-tailed alpha of 0.05, and data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2.

Funding Statement

This research was not funded by any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the HCPs for their active participation and cooperation in this study.

Author’s statement

TM has started the idea, designing, and conducting the study, performed the analyses, and manuscript writing. Also, TM finalized the manuscript which was subsequently approved by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

MA has role in designing the study, methodology, and manuscript writing.

TH has role in literature review, methodology, and manuscript writing.

GS has role in the methodology, some of the analyses, and manuscript writing.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Hepatitis B factsheet n.d.. [accessed 2017 April18] http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/

- 2.Lai CL, Ratziu V, Yuen MF, Poynard T.. Viral hepatitis B. Lancet. 2003;362:2089–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization World Hepatitis Summit harnesses global momentum to eliminate viral hepatitis n.d.. [accessed 2017 January1] http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/eliminate-viral-hepatitis/en/ [PubMed]

- 4.Aljofan M, Netter HJ, Aljarbou AN, Hadda TB, Orhan IE, Sener B, Mungall BA.. Anti-hepatitis B activity of isoquinoline alkaloids of plant origin. Arch Virol. 2014;159:1119–28. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1937-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salama II, Sami SM, Said ZN, Salama SI, Rabah TM, Abdel-Latif GA, Elmosalami DM, Saleh RM, Abdel Mohsin AM, Metwally AM, et al. Early and long term anamnestic response to HBV booster dose among fully vaccinated Egyptian children during infancy. Vaccine. 2018;36:2005–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for disease control and prevention Viral Hepatitis - Hepatitis B Information n.d.[accessed 2017 January2]. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/index.htm

- 7.Gm S, Aljofan M, Vr D, Alshammari T. Acute toxicity testing of newly discovered potential antihepatitis B virus agents of plant origin. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10:210–213. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang PC, Wei TY, Tseng TC, Lin HH, Wang CC. Cirrhosis has no impact on therapeutic responses of entecavir for chronic hepatitis B. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:946–50. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aljofan M, Lo MK, Rota PA, Michalski WP, Mungall BA. Off label antiviral therapeutics for henipaviruses: new light through old windows. J Antivir Antiretrovir. 2010;2:1–10. doi: 10.4172/jaa.1000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis JD, Enfield KB, Sifri CD. Hepatitis B in healthcare workers: transmission events and guidance for management. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:488–97. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas DL, Factor SH, Kelen GD, Washington AS, Taylor E Jr, Quinn TC. Viral hepatitis in health care personnel at The Johns Hopkins Hospital: the Seroprevalence of and risk factors for hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. JAMA Internal Medicine. 1993;153:1705–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pruss-Ustun A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y. Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:482–90. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang MH, Chen DS. Prevention of hepatitis B. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5:a021493. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruce MG, Bruden D, Hurlburt D, Zanis C, Thompson G, Rea L, Toomey M, Townshend-Bulson L, Rudolph K, Bulkow L, et al. Antibody levels and protection after hepatitis B vaccine: results of a 30-year follow-up study and response to a booster dose. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:16–22. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO position paper, weekly epidemiological record , 2017, 92,369-392, [accessed 2018 January2] http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255841/WER9227.pdf?sequence=1

- 16.Mast EE, Margolis HS, Fiore AE, Brink EW, Goldstein ST, Wang SA, Moyer LA, Bell BP, Alter MJ. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) part 1: immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt RM, Middleman AB. The importance of hepatitis B vaccination among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29:217–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adekanle O, Ndububa DA, Olowookere SA, Ijarotimi O, Ijadunola KT. Knowledge of Hepatitis B Virus Infection, Immunization with Hepatitis B Vaccine, Risk Perception, and Challenges to Control Hepatitis among Hospital Workers in a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. Hepat Res Treat. 2015;2015:439867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah HA, Abu-Amara M. Education provides significant benefits to patients with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:922–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aljumah AA, Babatin M, Hashim A, Abaalkhail F, Bassil N, Safwat M, Sanai FM. Hepatitis B care pathway in Saudi Arabia: current situation, gaps and actions. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:73–80. doi: 10.4103/sjg.SJG_421_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alfaleh F, Alshehri S, Alansari S, Aljeffri M, Almazrou Y, Shaffi A, Abdo AA. Long-term protection of hepatitis B vaccine 18 years after vaccination. J Infect. 2008;57:404–09. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerlich WH. Medical virology of hepatitis B: how it began and where we are now. Virol J. 2013;10:239. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morbidity and mortality report. CDC n.d.. [Accessed 2017 July3]. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6210a1.htm.

- 24.Al-Dharrab AA, Al-Samadani KH. Assessment of hepatitis B vaccination and compliance with infection control among dentists in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:1205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abeje G, Azage M. Hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and vaccination status among health care workers of Bahir Dar City Administration, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:30. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0756-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dannetun E, Tegnell A, Torner A, Giesecke J. Coverage of hepatitis B vaccination in Swedish healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect. 2006;63:201–04. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dannetun E, Tegnell A, Giesecke J. Parents’ attitudes towards hepatitis B vaccination for their children. A survey comparing paper and web questionnaires, Sweden 2005. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S, Basak D, Kumar A, Dasar P, Mishra P, Kumar A, Kumar Singh S, Debnath N, Gupta A. Occupational hepatitis B exposure: a peek into Indian Dental Students’ knowledge, opinion, and preventive practices. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2015;2015:190174. doi: 10.1155/2015/190174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Hazmi AH. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of primary health care physicians towards hepatitis B virus in Al-Jouf province, Saudi Arabia. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:288. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung JTC, Law CK. Revisiting knowledge, attitudes and practice (KAP) on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among female university students in Hong Kong. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:924–30. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1415685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Hazmi A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of medical students regarding occupational risks of hepatitis B virus in college of medicine, aljouf university. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2015;5:13–19. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.149765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drolet M, Benard E, Boily MC, Ali H, Baandrup L, Bauer H, Beddows S, Brisson J, Brotherton JM, Cummings T. Population-level impact and herd effects following human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:565–80. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71073-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- World Health Organization Hepatitis B factsheet n.d.. [accessed 2017 April18] http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/

- World Health Organization World Hepatitis Summit harnesses global momentum to eliminate viral hepatitis n.d.. [accessed 2017 January1] http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/eliminate-viral-hepatitis/en/ [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.