Abstract

Accumulation of neurotransmitter into synaptic vesicles is powered by the vacuolar proton ATPase. We show here that, in brain slices, application of the H+-ATPase inhibitors bafilomycin or concanamycin does not efficiently deplete glutamatergic vesicles of transmitter unless vesicle turnover is increased. Simulations of vesicle energetics suggest either that bafilomycin and concanamycin act on the H+-ATPase from inside the vesicle, or that the vesicle membrane potential is maintained after the H+-ATPase is inhibited.

Keywords: Glutamate, synaptic transmission, veratridine, potassium

Introduction

Fast synaptic transmission depends on the accumulation of neurotransmitter within vesicles, at concentrations of the order of 100mM, from a cytoplasmic transmitter concentration of ~10mM. This accumulation is powered by the action of the V-type H+-ATPase, which hydrolyses ATP and pumps H+ into the vesicle lumen [18], producing a high [H+] and positive membrane potential within the vesicle. Neutral transmitters such as GABA and glycine can then be accumulated via a vesicular transporter which exchanges intra-vesicular H+ for cytoplasmic transmitter [10, 13, 11], while negatively charged transmitters like glutamate are primarily accumulated using the energy provided by the voltage gradient across the vesicle membrane [17, 15, 27, 5, but see 4, 26, 28]. Inhibition of the H+-ATPase is expected to lead to a run-down of the proton and voltage gradient across the vesicle membrane, and thus to a loss of transmitter from the vesicles. Consistent with this, block of ATPase action with the plecomacrolide antibiotics bafilomycin and concanamycin [9] greatly reduces both spontaneous and evoked release of GABA in brain slices: the rate of mIPSCs is reduced by 84-94% and the amplitude of evoked IPSCs is reduced by 90% [30, 21, 2, 1]. We show here, however, that applying these antibiotics in the same way to brain slices does not fully deplete glutamate from vesicles, unless vesicle turnover is simultaneously stimulated. These data provide a method for using plecomacrolides (rather than the more toxic tetanus neurotoxin) to block excitatory synaptic transmission, and give insight into the mode of action of these drugs.

Methods

Electrophysiology

Exocytotic glutamate release was monitored by whole-cell clamping area CA1 pyramidal cells in 225μm hippocampal slices from P12 rats. Pipette solution contained (mM): 135 CsCl, 4 NaCl, 0.5 CaCl2,10 Hepes, 5 Na2EGTA, 2 MgATP and 0.5 Na2GTP, 10 QX-314 (to suppress voltage-gated sodium currents), pH set to 7.2 with CsOH. Experiments were at 25°C, with the slices submerged in flowing (3ml/min) extracellular solution containing (mM): NaCl 126, NaHCO3 24, NaH2PO4 1, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 2, D-glucose 10 (gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2), pH 7.4. Kynurenic acid (1mM, Sigma, UK) was included in the dissection solution (to block glutamate receptors, to reduce potential excitotoxic damage) but was omitted from the superfusion and the pre-soaking solution. For experiments using bafilomycin or concanamycin to block vesicle loading with transmitter, slices were pre-soaked for at least 2.5 hours in 4μm bafilomycin (Tocris, Bristol, UK) or 2μM concanamycin (ICN Biomedicine, Aurora, OH) while control slices were soaked in external solution lacking the drug; drugs were made up respectively as a 400μM and 200μM stock in DMSO and a corresponding amount of DMSO was added to the control pre-soaking solution. Bafilomycin or concanamycin were not present in the subsequent recording solution for cost reasons; typically it took ~8 mins to locate and record from a cell after removing the slice from the soaking solution (during which time there will be some washout of bafilomycin/concanamycin). In some experiments, for 5 mins of the 2.5 hours pre-soaking, 10μM veratridine (Sigma, UK) or 10mM KCl were added to the soaking solution (both the solution containing bafilomycin or concanamycin, and the “control” solution lacking this agent). Cells were voltage-clamped at -33mV, using pipettes with a series resistance (after ~70% compensation) of ~3MΩ. Synaptic input from the Schaffer collaterals was evoked at a frequency of 0.1Hz using a concentric bipolar stimulating electrode which was placed at a standardized position in the Schaffer collaterals before recording from the pyramidal cell. IPSCs were abolished by including 100μM picrotoxin in the superfusion solution to block GABAA receptors. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

Simulating vesicular transmitter accumulation

To simulate accumulation of glutamate into vesicles by the vesicular H+-ATPase, and the effect of blocking the ATPase, we initially assumed that the ATPase can pump protons into a vesicle of radius 15nm at a rate sufficient to raise the free [H+] in the vesicle at 1μM/sec, assuming that only 1 in 2000 H+ entering remains unbuffered (corresponding to an approximate buffering power of 20mM/pH unit), i.e. a proton current of Imax=2.7.10-18 amps (or 17 protons/sec). The value of pump rate chosen is not critical for the qualitative results presented; this value was used because in the presence of ATP glutamatergic vesicles acidify to a pH of 5.5 to 5 on a time scale of 4 to 60 sec [15, 24, 3, but see 26 for a smaller pH gradient], and this magnitude of proton current (when combined with the charge compensating conductances described below) produces acidification to about pH 5.5 in 4 sec and to pH 5 in 20 sec (Fig. 3). For consistency with the thermodynamic constraint that the ATPase can only pump protons against the transmembrane H+ and voltage gradient if the energy available from ATP is greater than the energy needed to move an assumed 2 H+/ATP across the membrane, this ATPase-mediated proton current was multiplied by a factor

where EATP is the energy provided per ATP (50kJ/mole), and the subsequent terms are the energy needed to accumulate 2 H+ against the [H+] and voltage gradient across the vesicle membrane (R is the gas constant, T is temperature, F is the Faraday, [H+]i is the free proton concentration in the vesicle, [H+]o is the cytoplasmic [H+], and V is the potential inside the vesicle relative to the cytoplasm: the exact expression assumed to define the thermodynamic constraint is not critical for the results obtained). As [H+]i and V increase, the two subsequent terms become significant compared to EATP and proton pumping is reduced. Glutamate is accumulated in vesicles primarily using the voltage gradient generated by the H+-ATPase [17, 15, 27, 5, but see 4, 26, 28]. The vesicle membrane was therefore assumed to have a conductance to glutamate of gGlu = 2.25.10-16 S (reflecting the vesicular glutamate transporter), and in some simulations a conductance to H+ of gH = 4.5.10-18 S or a Cl- conductance of gCl = 2.25.10-17 S (these magnitudes were chosen to produce a significant effect on glutamate accumulation, and do not have to be accurate to give insight into the effect of including a proton or Cl- conductance). The cytoplasmic [H+], [glutamate-], and [Cl-] were set to 10-7M, 10mM, and 10mM respectively. Simulations were started by assuming that exocytosis, by equilibrating the vesicle contents with the extracellular space, set the intravesicular [H+], [glutamate-], and [Cl-] to 10-7.4M, 100μM (the exact value assumed for [glutamate-] was not critical for the results obtained) and 140mM respectively. At any moment the vesicular membrane potential was calculated as the potential at which there was zero current flow across the vesicle membrane,

where I(t) = Imax when the ATPase is working, or zero when it is blocked. The differential equations describing the rate of change of intravesicular [H+], [glutamate-] and [Cl-] were solved using MathCad, for 100 sec during which the ATPase operated, followed by 100 sec when it was blocked.

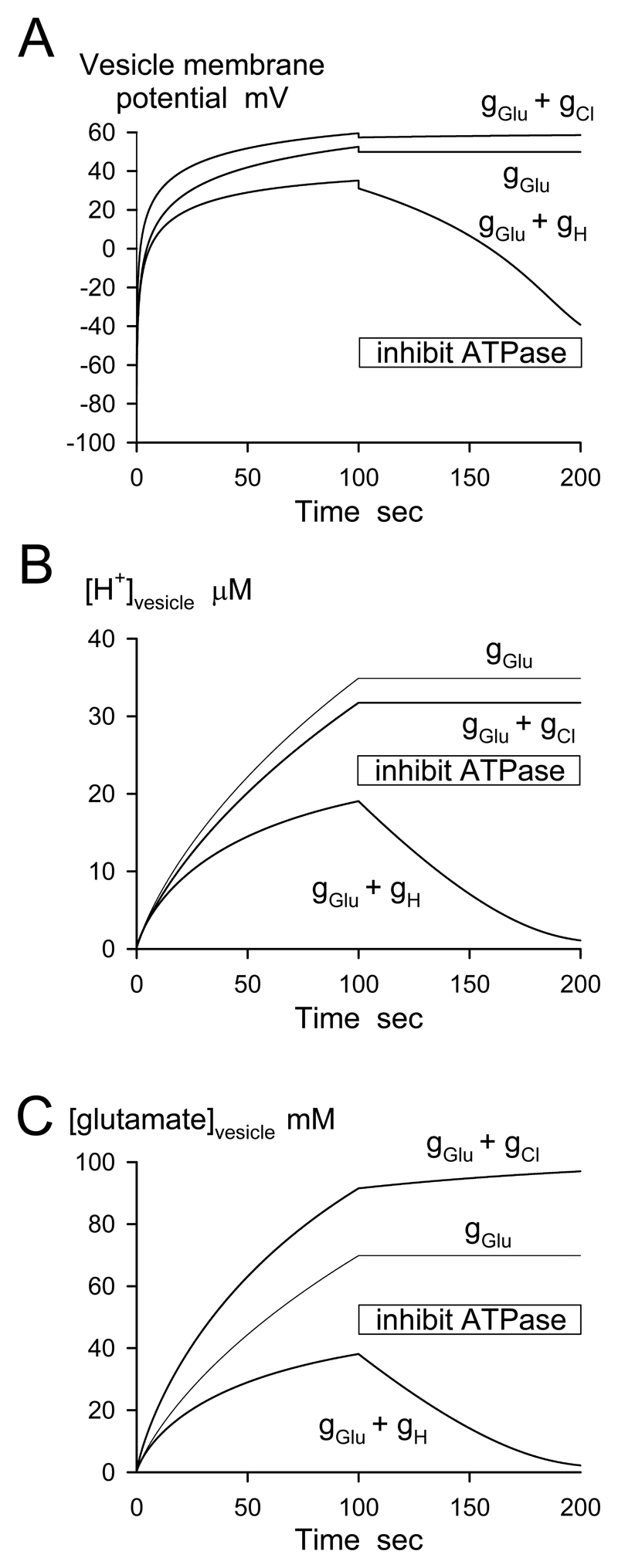

Figure 3. Simulation of the effect of blocking the vesicular ATPase on the vesicle.

A Membrane potential, B [H+], and C glutamate accumulation. At time zero, exocytosis is assumed to equibibrate the vesicle contents with the extracellular space. The vesicle membrane potential is initially negative because vesicular [glutamate] is lower than that in the cytoplasm. The ATPase energises the vesicle for 100 sec and is then blocked (“inhibit ATPase”). Simulations are shown for a vesicle with conductance (g) to glutamate only, to glutamate and H+, or to glutamate and Cl-.

Results

The action of bafilomycin and concanamycin is promoted by vesicle turnover

Activating the Schaffer collaterals with increasing strength stimuli evoked an EPSC of increasing size in pyramidal cells (Fig. 1A, B). In interleaved slices soaked in 4μM bafilomycin for 2 hours, although there was a tendency for the EPSC size to be reduced (Fig. 1A, Baf), the reduction was not significant (Fig. 1B). If, however, while pre-soaking in bafilomycin the slices were exposed to veratridine for 5 mins at the beginning of the soaking period, then the Schaffer collateral EPSCs were almost abolished compared to slices exposed to veratridine alone (Fig. 1C, 1D). Veratridine alone (in the absence of bafilomycin) did not affect the EPSC size (which was 295±51 and 260±54 pA at 100 V stimulation strength, for 23 and 14 cells studied with and without veratridine present for 5 mins, not significantly different: p=0.66). Veratridine reduces voltage-gated sodium channel inactivation, inducing neuronal action potential firing, which will evoke vesicular release. This suggested that the promotion of the inhibitory action of bafilomycin by the presence of veratridine might be a result of an increase in the rate of vesicle cycling.

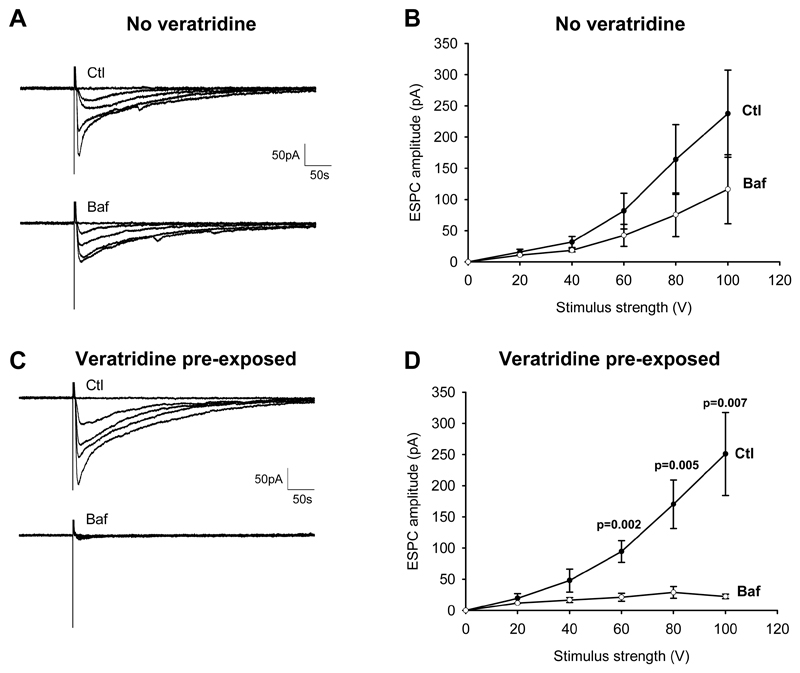

Figure 1. Effect of veratridine on glutamatergic vesicles depletion by bafilomycin.

A, Synaptic currents evoked at -33mV in CA1 pyramidal neurons by increasing strength of stimulation (at 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100V) of the Schaffer collaterals (in the presence of 100 μM picrotoxin to block GABAA receptors), in control (Ctl) solution or after soaking slices in 4 μM bafilomycin (Baf) alone. B, Mean EPSCs from experiments as in A (10 control cells, 10 interleaved bafilomycin cells). C, When veratridine (10 μM) was added to the pre-soaking solution for 5 min, EPSCs were almost abolished in bafilomycin-treated cells. D, Mean data from experiments as in C (10 control cells, 10 interleaved bafilomycin cells).

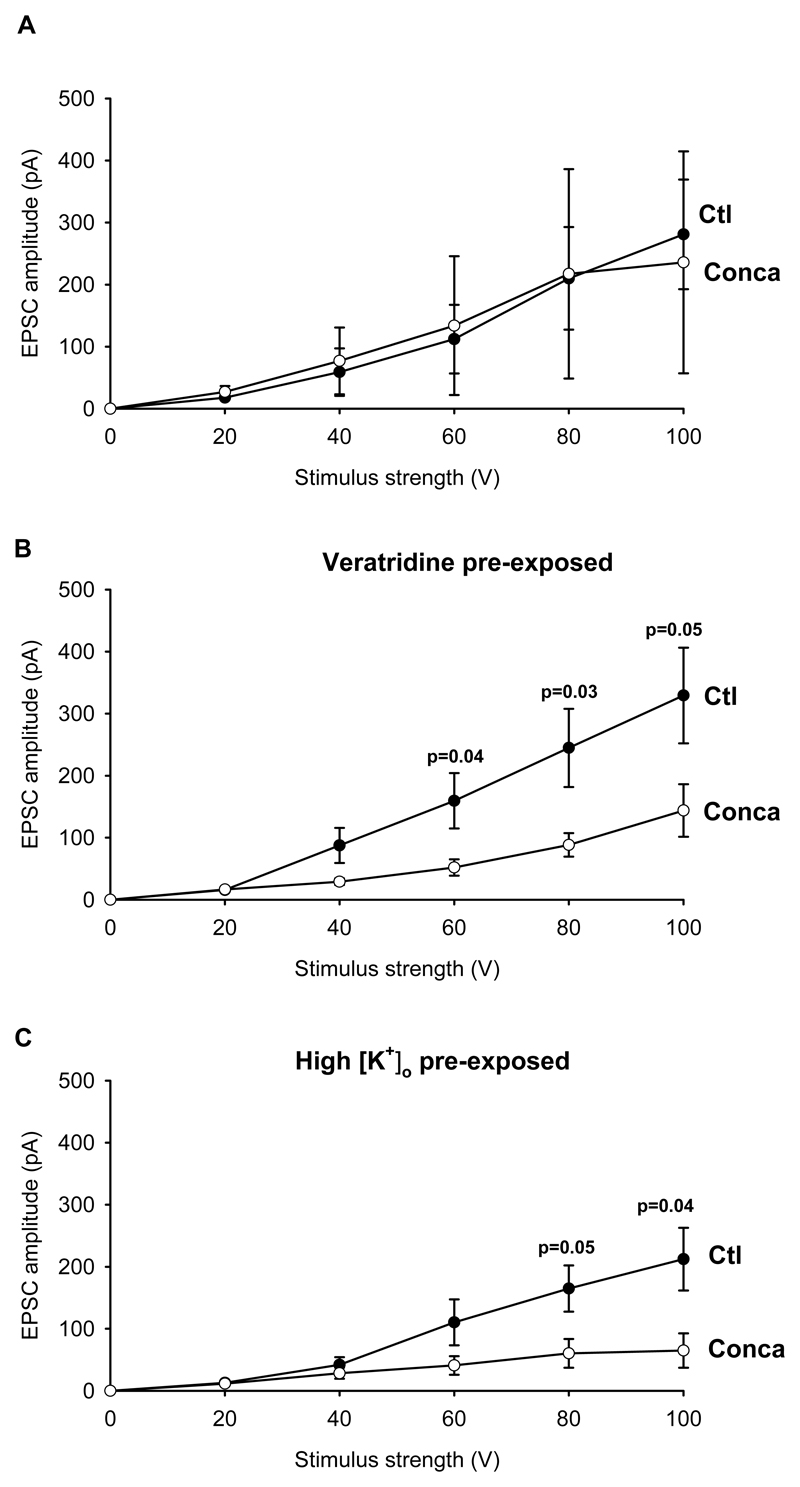

To investigate this possibility further, we examined the effect of the related plecomacrolide concanamycin on EPSCs. As for bafilomycin, pre-soaking in 2μM concanamycin did not significantly alter the size of Schaffer collateral EPSCs (Fig. 2A). However, brief exposure to veratridine (Fig. 2B), or to an elevated (12.5mM) [K+] solution (Fig. 2C), during the concanamycin exposure led to the EPSC being significantly reduced (although not as reduced as in 4μM bafilomycin), compared to exposure to veratridine alone or elevated [K+] alone (which had no effect on the EPSC, 212±50 and 260±54 pA at 100 V stimulation strength, for 5 and 14 cells studied with and without K+ present for 5 mins in the absence of concanamycin, not significantly different: p=0.62). Like veratridine, elevated [K+] will depolarize neurons and evoke action potentials. The fact that both veratridine and high [K+] increase the effect of bafilomycin/concanamycin is consistent with both manipulations acting by increasing vesicle turnover.

Figure 2. Effects of veratridine and elevated [K+] solution on glutamatergic vesicle depletion by concanamycin.

A, Soaking slices in 2μM concanamycin alone had no significant effect on the amplitude of the glutamatergic EPSCs evoked in CA1 pyramidal neurons at -33mV by stimulating the Schaffer collaterals with increasing intensity (4 control cells (Ctl), 4 interleaved concanamycin cells (Conca)). B, When 10 μM veratridine was added to the soaking solution for 5 min, significantly smaller EPSCs were recorded in concanamycin-treated cells than control cells (13 control cells, 10 interleaved concanamycin cells). C, When slices were exposed to an elevated [K+] solution for 5 min at the beginning of the soaking period, significantly smaller EPSCs were recorded in concanamycin-treated cells than in control cells (5 control cells, 5 interleaved concanamycin cells).

Simulations of vesicle energetics

Glutamate and GABA are accumulated into vesicles using different energetic components of the proton motive force set up across the vesicle membrane by the H+-ATPase, i.e. the voltage gradient and the proton gradient, respectively (see Introduction). To investigate how these gradients dissipate when the H+-ATPase is inhibited, we simulated the vesicle energetics making different assumptions for the ionic permeability of the vesicle membrane, as described in the Methods.

With the vesicle membrane permeable solely to glutamate (reflecting the presence of the vesicular glutamate transporter), after exocytosis the vesicular ATPase was predicted (for the parameters assumed) to polarize the vesicle membrane to +50mV, to raise the free proton concentration in the vesicle to 35μM, and to accumulate 70mM glutamate in the vesicle (Fig. 3A-C). On blocking the ATPase, although there is predicted to be initially a few mV loss of vesicle potential due to block of the ATPase-generated proton current, these gradients are essentially maintained for ever. This is because the vesicle membrane is solely permeable to glutamate and so remains at the Nernst potential set by the glutamate gradient that has been established. In this situation, even in the presence of an ATPase blocker, glutamate would only be lost from the vesicle, and the vesicle transmembrane gradients will only be abolished, when exocytosis occurs. Thus, a high level of vesicle turnover would promote the irreversible loss of glutamate from vesicles.

Including a small vesicular permeability to H+ (2% of the conductance assumed to be provided by the vesicular glutamate transporter), to allow some of the pumped in H+ to leak out again, reduced the accumulated glutamate concentration after 100 sec operation of the ATPase below 40mM, and led to the vesicle potential, proton and glutamate gradients decaying in 100 sec after the ATPase was inhibited (Fig. 3). In this situation, therefore, it would not be necessary to have vesicle turnover for loss of glutamate from vesicles to occur when the ATPase is blocked.

Finally, since vesicles have been suggested to have a Cl- conductance [25], we simulated the effect of the vesicle having a Cl- conductance that was 10% of the conductance to glutamate (and having no H+ conductance). This increased the accumulation of glutamate, and led to vesicular glutamate being maintained after the ATPase was inhibited, implying that vesicle turnover would again be needed to deplete vesicles of glutamate in the presence of ATPase blockers. However, repeating the simulation with no ATPase present in the membrane showed that about 2/3 of the glutamate accumulation produced in this situation reflects exchange of cytoplasmic glutamate for intravesicular Cl-, which is initially assumed to be set to 140mM when the preceding exocytosis equilibrates the vesicle contents with the extracellular fluid (simulation not shown).

Thus, whether transmitter is lost rapidly from vesicles when the ATPase is inhibited depends on the permeability of the vesicle membrane to different ions, and on the rate of vesicle turnover.

Discussion

Bafilomycin and concanamycin effectively deplete GABAergic vesicles of transmitter in brain slices, reducing the frequency of spontaneous IPSCs by 84-94% and reducing the amplitude of evoked IPSCs by ~90% [30, 21, 2]. By contrast, bafilomycin or concanamycin alone did not deplete glutamatergic vesicles of transmitter sufficiently to significantly reduce evoked EPSCs (Fig. 1B, 2A).

A priori, there are several possible reasons for this difference. First, postsynaptic GABAA receptors might be less saturated than glutamate’s AMPA receptors by the peak transmitter concentration reached in the synaptic cleft, so that a reduction of vesicular transmitter content could affect IPSCs more than EPSCs. However, recent work suggests that neither AMPA nor GABAA receptors are saturated [14, 19, 22]. Second, glutamate and GABA are accumulated into vesicles using different energetic components of the proton motive force set up across the vesicle membrane by the H+-ATPase, i.e. the voltage gradient and the proton gradient, respectively (see Introduction). However, the voltage gradient produced by the ATPase might be expected to dissipate faster than the proton gradient when the H+-ATPase is inhibited (because inhibiting the ATPase current will immediately produce some voltage change, whereas it will take some time for the proton gradient to dissipate), suggesting that this difference would result in vesicles losing glutamate faster than GABA. Finally, the difference could reflect GABAergic neurons being more spontaneously active, or having more spontaneous transmitter release, than glutamatergic neurons, if vesicle turnover is necessary for bafilomycin and concanamycin to act. Consistent with this possibility, although hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells receive far more excitatory (30,000) than inhibitory (1,700) synapses [16], 97% of spontaneous postsynaptic currents recorded in these cells are produced by release from GABAergic neurons [20, 8, 1].

Our observation that depolarizing neurons, either with veratridine or high [K+], during exposure to bafilomycin or concanamycin results in these agents successfully depleting vesicles of glutamate suggests that vesicle turnover promotes the action of bafilomycin and concanamycin. Consistent with this, suppression of EPSCs is produced by bafilomycin if synaptic transmitter release is evoked electrically during the application of bafilomycin [12]. In cultured neurons Zhou et al. [30] reported that bafilomycin could deplete glutamate from vesicles: this may reflect more spontaneous activity, causing vesicle turnover, in excitatory neurons in culture than in our hippocampal slices.

There are two possible explanations for this effect of vesicle turnover. First, the action of these agents may be limited by their access to the H+-ATPase. The ATPase is composed of a large multi-subunit cytoplasmic domain, attached to a smaller intramembrane domain composed of a and c subunits [18]. Bafilomycin and concanamycin are thought to block H+ flow across the membrane by binding to the c and a subunits [7, 29, 6], and it is plausible that access to the binding site can only be obtained from the intra-vesicular side of the membrane. In this case extracellularly applied bafilomycin/concanamycin would only act if vesicles are being exocytosed, so that they expose the interior of their volume to the extracellular fluid. Alternatively, the need for vesicle turnover might reflect the time needed for the transmitter gradient across the vesicle membrane to run down when the ATPase is inhibited. Simulating vesicle energetics (Fig. 3) suggested that if the vesicle membrane is permeable to glutamate and protons then on inhibiting the vesicular ATPase the vesicles will lose glutamate rapidly. However, if the vesicle membrane is permeable solely to glutamate, or to glutamate and Cl-, then intravesicular glutamate will be maintained for an extended period on inhibition of the ATPase. In this case vesicles will only lose glutamate, and the vesicular transmembrane voltage and proton gradients will only be irreversibly lost, when exocytosis occurs, and rapid vesicle turnover will promote the action of bafilomycin/concanamycin. Consistent with this, vesicle alkalinization produced by bafilomycin alone is much slower than the alkalinization produced by electrical stimulation in the presence of bafilomycin [23, Fig. 2C].

In addition to giving insight into the mode of action of the plecomacrolide antibiotics, our data provide a useful method for altering excitatory transmission. Combining bafilomycin with veratridine treatment to enhance vesicular turnover effectively suppresses EPSCs (Fig. 1C). This provides a useful alternative to the use of tetanus neurotoxin for the inhibition of vesicular glutamate release.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the Wellcome Trust, the EU and a Wolfson-Royal Society Award. We thank Andrea Volterra for suggesting promotion of vesicle turnover as a means of improving the action of bafilomycin.

References

- [1].Allen NJ, Attwell D. The effect of simulated ischaemia on spontaneous GABA release in area CA1 of the juvenile rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2004;561:485–498. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.070490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Allen NJ, Rossi DJ, Attwell D. Sequential release of GABA by exocytosis and reversed uptake leads to neuronal swelling in simulated ischemia of hippocampal slices. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3837–3849. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5539-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Atluri PP, Ryan TA. The kinetics of synaptic vesicle vesicle reacidification at hippocampal nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2313–2320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4425-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bai L, Xu H, Collins JF, Ghishan FK. Molecular and functional analysis of a novel neuronal vesicular glutamate transporter. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36764–36769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bellocchio EE, Reimer RJ, Fremeau RT, Jr, Edwards RH. Uptake of glutamate into synaptic vesicles by an inorganic phosphate transporter. Science. 2000;289:957–960. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bowman EJ, Graham LA, Stevens TH, Bowman BJ. The bafilomycin/concanamycin binding site in subunit c of the V-ATPases from Neurospora crassa and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33131–33138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Crider BP, Xie XS, Stone DK. Bafilomycin inhibits proton flow through the H+ channel of vacuolar proton pumps. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17379–17381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].De Simoni A, Griesinger GB, Edwards FA. Development of rat CA1 neurones in acute versus organotypic slices: role of experience in synaptic morphology and activity. J Physiol. 2003;550:135–147. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Drose S, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins and concanamycins as inhibitors of V-ATPases and P-ATPases. J Exp Biol. 1997;200:1–8. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fykse EM, Fonnum F. Uptake of gamma-aminobutyric acid by a synaptic vesicle fraction isolated from rat brain. J Neurochem. 1988;50:1237–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb10599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gasnier B. The SLC32 transporter, a key protein for the synaptic release of inhibitory amino acids. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:756–759. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Harrison J, Jahr CE. Receptor occupancy limits synaptic depression at climbing fibre synapses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:377–383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00377.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hell JW, Maycox PR, Jahn R. Energy dependence and functional reconstitution of the gamma-aminobutyric acid carrier from synaptic vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2111–2117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liu G, Choi S, Tsien RW. Variability of neurotransmitter concentration and nonsaturation of postsynaptic AMPA receptors at synapses in hippocampal cultures and slices. Neuron. 1999;22:395–409. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Maycox PR, Deckwerth T, Hell JW, Jahn R. Glutamate uptake by brain synaptic vesicles. Energy dependence of transport and functional reconstitution in proteoliposomes. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15423–15428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Megias M, Emri Z, Freund TF, Gulyas AI. Total number and distribution of inhibitory and excitatory synapses on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Neuroscience. 2001;102:527–540. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Naito S, Ueda T. Adenosine triphosphate-dependent uptake of glutamate into protein I-associated synaptic vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:696–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nelson N. Structure and pharmacology of the proton-ATPases. Trends Pharm Sci. 1991;12:71–75. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90501-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pankratov YV, Krishtal OA. Distinct quantal features of AMPA and NMDA synaptic currents in hippocampal neurons: implication of glutamate spillover and receptor saturation. Biophys J. 2003;85:3375–3387. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74757-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ropert N, Miles R, Korn H. Characteristics of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents in CA1 pyramidal neurones of rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1990;428:707–722. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rossi DJ, Hamann M, Attwell D. Multiple modes of GABAergic inhibition of rat cerebellar granule cells. J Physiol. 2003;548:97–111. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rumpel E, Behrends JC. Postsynaptic receptor occupancy during evoked transmission at striatal GABAergic synapses in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:771–779. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.2.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sankaranarayanan S, Ryan TA. Calcium accelerates endocytosis of vSNAREs at hippocampal synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:129–136. doi: 10.1038/83949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schoonderwoert VThG, Martens GJM. Proton pumping in the secretory pathway. J Memb Biol. 2001;182:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stobrawa SM, Breiderhoff T, Takamori S, Engel D, Schweizer M, Zdebik AA, Bosl MR, Ruether K, Jahn H, Draguhn A, Jahn R, et al. Disruption of ClC-3, a chloride channel expressed on synaptic vesicles, leads to a loss of the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;29:185–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tabb JS, Kish PE, van Dyke R, Ueda T. Glutamate transport into synaptic vesicles: roles of membrane potential, pH gradient and intravesicular pH. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15412–15418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Takamori S, Rhee JS, Rosenmund C, Jahn R. Identification of a vesicular glutamate transporter that defines a glutamatergic phenotype in neurons. Nature. 2000;407:189–194. doi: 10.1038/35025070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wolosker H, de Souza DO, de Meis L. Regulation of glutamate transport into synaptic vesicles by chloride and proton gradient. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11726–11731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhang J, Feng Y, Forgac M. Proton conduction and bafilomycin binding by the V0 domain of the coated vesicle V-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23518–23523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhou Q, Petersen CC, Nicoll RA. Effects of reduced vesicular filling on synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 2000;525:195–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]