Abstract

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is an acquired autoimmune disease mediated by antibodies against the patient’s red blood cells. However, the underlying mechanisms for antibody production are not fully understood. Previous studies of etiology and pathogenesis of AIHA mainly focus on autoreactive B cells that have escaped tolerance mechanisms. Few studies have reported the function of TFH and TFR cells in the process of AIHA. The present study aimed to explore the potential mechanism of TFH and TFR cells in the pathogenesis of AIHA. With the model of murine AIHA, increased ratios of TFH:TFR, elevated serum IL-21 and IL-6 levels, and upregulated Bcl-6 and c-Maf expression were reported. Also, adoptive transfer of purified CD4+CXCR5+CD25- T cells from immunized mice promoted the induction of autoantibody in the AIHA mouse model. Altogether, our data demonstrate the important role of TFH cells for control and induction of AIHA. In the light of the key contributions of TFH cells to the immune response in AIHA, strategies aimed at inhibiting the TFH development or function should be emphasized.

Subject terms: Cytokines, Immunopathogenesis

Introduction

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is an acquired autoimmune disease resulting in the production of antibodies directed against the patient’s red blood cells (RBCs) causing shortened erythrocyte lifespan1–3. The most common form of AIHA is warm AIHA characterized by the presence of warm-type autoantibodies—immunoglobulin G (IgG) which reacts optimally at 37 °C, causing RBC extravascular destruction by tissue macrophages4,5. The main treatment of AIHA includes RBC transfusion and immune system inhibitors such as corticosteroids. Transfusion of RBC in AIHA patients is challenging as the autoantibodies in the patients are often reactive to the transfused RBCs, making every unit of blood incompatible. Moreover, the relapse rate is as high as 50% in patients refractory to steroids6–8. Thus, there is an urgent need to understand the mechanism of autoantibody production in AIHA so that better therapies can be designed.

Previous studies of the etiology and pathogenesis of AIHA have focused on the autoreactive B cells that have escaped tolerance mechanisms and regulatory T cells (Treg)9. Few studies have reported the function of T follicular helper cells (TFH) and T follicular regulatory cells (TFR) in the process of AIHA. A highly specialized CD4+ T cell subpopulation, TFH, has recently received immense attention, as they play important role in the regulation of germinal center (GC) reactions and antibody production. TFH cells are characterized by the expression of the transcription factor the nuclear transcriptional repressor B cell lymphoma 6 (Bcl-6), the chemokine receptor chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 5 (CXCR5), inducible co-stimulator (ICOS), programmed cell death protein-1(PD-1), and production of high levels of interleukin 21 (IL-21)10–13. Of the cytokine signaling, interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL-21 play a critical role in TFH differentiation and function maintenance because of the upregulation of Bcl-6 and CXCR5 expression through signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)14–17. The main functions of TFH cells are to support GC formation and reactions, provide B cells with essential maturation signals, drive antibody class switching, govern the generation of high-affinity antibodies, and promote memory formation13,18–20.

TFR cells represent a highly specialized subpopulation of Foxp3+ Tregs that co-express TFH features, such as Bcl-6, CXCR5, ICOS, PD-1 and Treg features CD25 and Foxp321. TFR cells have the ability to inhibit TFH activation and cytokines production and suppress B cell GL7 and B7-1 expression and limited class switch recombination occurring in the GC via high expression of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and production of inhibitory cytokine— interleukin 10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factorβ (TGFβ)22,23. The involvement of TFR cells in the pathogenesis of human autoimmune diseases remains speculative, but an alteration of the TFR:TFH ratio is observed in the blood of patients suffering from several autoimmune diseases, such as child immune thrombocytopenia24, and rheumatoid arthritis25.

Considering over-activation of B cells and overproduction of autoantibodies, we hypothesize TFH and TFR cells play a vital role in the process of AIHA. Here, we utilize the murine AIHA model to determine the role of TFH and TFR for the induction of AIHA. Our research has demonstrated that there is an increased ratio of TFH:TFR, elevated serum IL-21 and IL-6 levels, and upregulated Bcl-6 and c-Maf expression at the transcriptive levels in autoantibody-positive AIHA mouse. In addition, adoptive transfer of purified CD4+CXCR5+CD25− T cells, but not CD4+CXCR5-CD25− T cells, from immunized mice promoted the induction of autoantibody in the AIHA mouse model. Altogether, our data demonstrate the important role of TFH cells for the control and induction of AIHA. In the light of the key contributions of TFH cells to the immune response in AIHA, strategies aimed at inhibiting the TFH development or function should be emphasized for the treatment of AIHA.

Results

Expression of CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH cells in AIHA mouse model

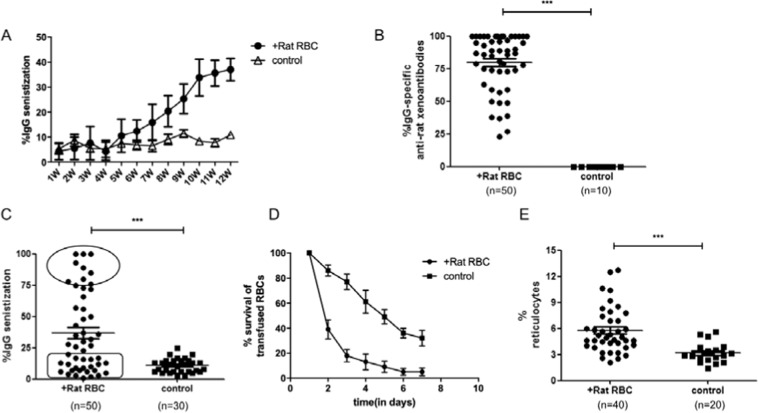

To study the role of TFH in AIHA, an AIHA mouse model was constructed according to the method described previously26,27. In our model, erythrocyte autoantibodies were detectable within 5-6 weeks and constantly increased in the following six weeks. In the twelfth week, nearly all the mice developed rat RBC-specific xenoantibodies, and approximately 40% of mice developed AIHA, as evidenced by the presence of red cell-specific autoantibodies on their RBCs, increased destruction of transfused mouse RBCs, and increased levels of circulating reticulocytes (Fig. 1A–E).

Figure 1.

Development of the AIHA mouse model. Female C57BL/6J mice aged 8-10 weeks were immunized on a weekly basis with rat RBCsfor 12 weeks. (A) Level of IgG-specific autoantibodies on mouse RBCs was measured by flow cytometry on the day before rat RBCs injection and expressed as percentage of background unstained cells. This experiment was repeated three times with at least 10 mice for each group each time. (B) Levels of IgG-specific anti–rat xenoantibodies in plasma were measured by first incubating rat erythrocytes with diluted mouse plasma followed by staining with FITC-conjugated anti–mouse IgG. The analysis was performed by flow cytometry and the percentage of rat RBCs that have antibodies bound to them is shown on the Y-axis. (C) Theexpression of IgG-specific autoantibodies on mouse RBCs at week 12. Each plot represents one mouse in each group. The oval box represents the cohort with the highest levels of autoantibodies, whereas the square box includes the group with background control levels of autoantibodies. (D) Red cell survival studies were performed using PKH-26 labeled C57BL/6J mouse RBCs transfused into mice immunized with rat RBCs or PBS as a negative control.At times indicated, venous blood was sampled and analyzed by flow cytometry for the fraction of fluorescent RBCs. To show the RBCs clearance kinetics, detectable RBCs at 1 minute after injection were defined as 100%, and the remaining RBCs were calculated at different time points by divided the total RBCs. This experiment was repeated three times with two mice in each group. (E) Numbers of circulating reticulocytes in mice expressed as a percentage. Data shown were the mean ± SEM. The horizontal lines show the median.

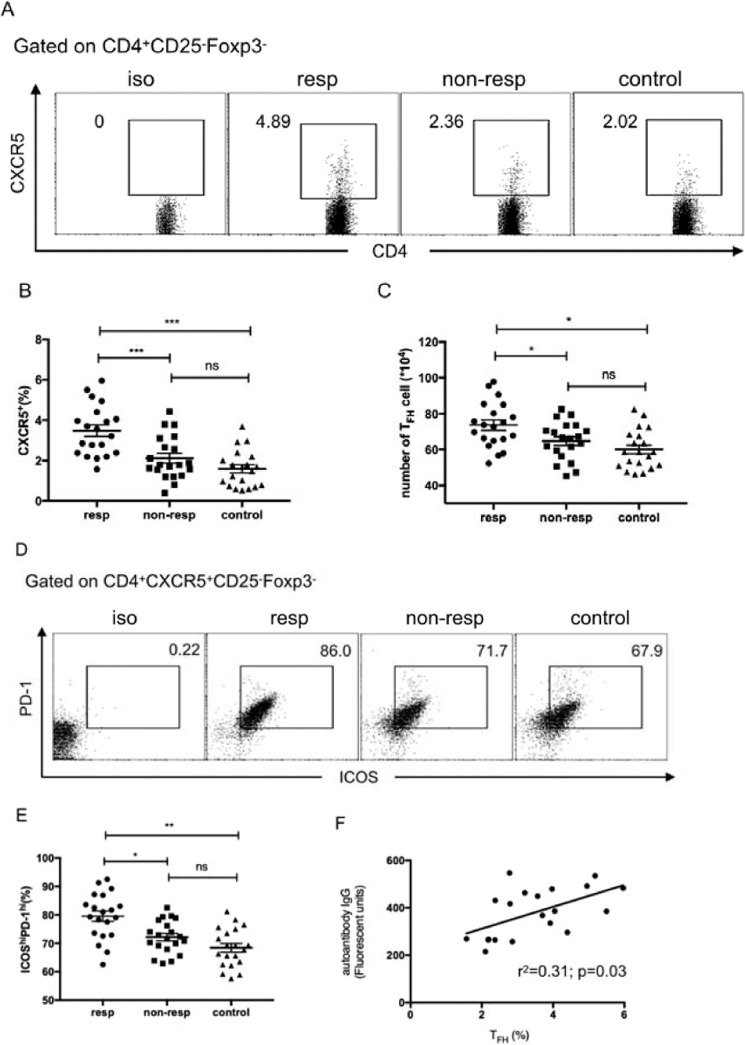

In order to investigate the potential TFH-associated differences in AIHA mouse model, transfused recipients were grouped as either non-responder (no autoantibodies) or responder (more than 75% erythrocyte with red cell-specific autoantibodies).The percentage of CD4+CXCR5+CD25−Foxp3− TFH cells was analyzed by flow cytometry in these groups. As shown in Fig. 2A–C, the percentage and number of CD4+CXCR5+CD25−Foxp3− TFH cells in the responder group were significantly increased compared with the non-responder and control groups. The proportion of ICOShiPD-1hi cells was also higher in the responder group than that of the non-responder and control groups (Fig. 2D,E). Further analysis found that there was a moderate and positive correlation between the percentage of CD4+CXCR5+CD25−Foxp3− TFH cell and autoantibody fluorescence intensity in the responder group (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Increased TFH cells in autoantibody-positive AIHA mice. (A) The expression of CXCR5 in spleen CD4+CD25−FoxP3−T cells from the responder, non-responder, and control groups. (B) The percentages of CXCR5+ cells in CD4+CD25−FoxP3− cells in these three groups. (C) The number of CD4+CXCR5+ CD25−FoxP3−TFH cells in spleen in these three groups. (D) The expression of ICOS and PD-1 in CD4+CXCR5+ CD25−FoxP3−TFH cells from these three groups. (E) The percentages of ICOShiPD-1hi cells in spleen CXCR5+CD4+CD25−FoxP3−T cells in these three groups. (F) Relationship of the percentage of CXCR5+CD4+CD25−FoxP3− TFH cells and the fluorescent units of IgG-specific autoantibodies in the responder group. This experiment was repeated three times with 6-7 mice for each group and each plot represents one mouse in each group. Data shown were the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; ns, no significance.

Expression of CD4+CXCR5+FoxP3+ cells in AIHA mouse model

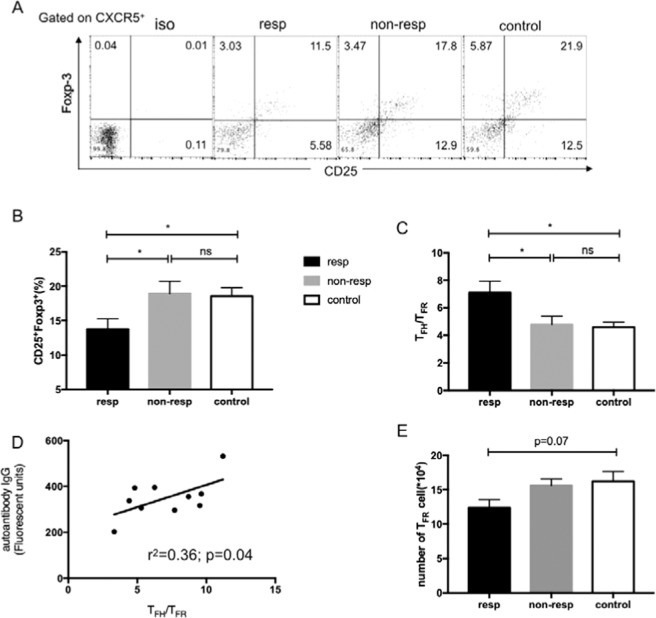

TFR cells share features of both TFH and Treg cells, localize to B-cell follicle, and regulate the size of the TFH cell population and antibody response in vivo. So we tested whether increased TFH population and autoimmune response in the AIHA mouse model were because of the shrunken TFR subset. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, the percentage of CD25+ and Foxp3+ cells within the CD4+CXCR5+ T subset was lower in the responder group than that of the non-responder and control groups.The ratio of TFH:TFR was higher in the responder group, and also, this ratio had a moderate and positive correlation to autoantibody fluorescence intensity in the responder’s group (Fig. 3C,D). Further analysis pointed out that the number of TFR cells slightly decreased in the responder group (Fig. 3E), suggesting the decreased proportion of TFR cell was because of expanded TFH cells.

Figure 3.

Decreased TFR cells in autoantibody-positive AIHA mice. (A) The expression of CD25 and Foxp3 in CXCR5+CD4+T cells from mice in the responder, non-responder, and control groups. (B) The percentages of CD25+Foxp3+ cells in CXCR5+CD4+T cells in these three groups. (C) The ratio of TFH:TFR in these three groups. (D) Relationship of TFH:TFR and the fluorescent units of IgG-specific autoantibodies in responder the group. (E) The number of CD4+CXCR5+CD25+FoxP3+TFR cells in spleen in these three groups. Experiments were repeated three times with 3–4 mice for each group. Data shown were the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; ns, no significance.

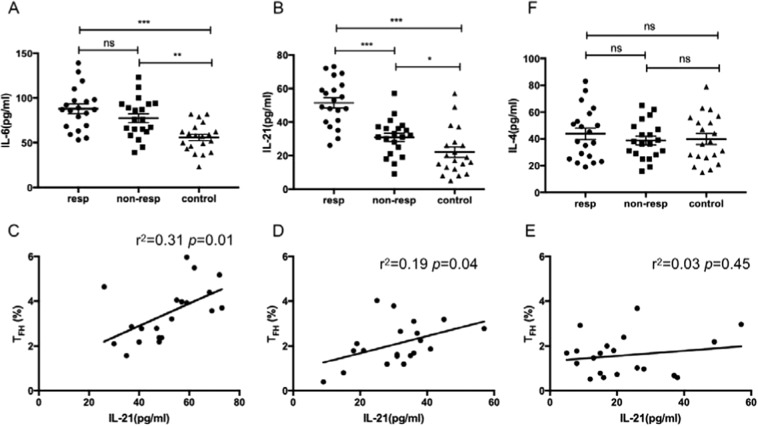

Serum IL-4, IL-6 and IL-21 levels in the AIHA mouse model

Recent studies16,28 have indicated that the cytokines IL-6 and IL-21 play important roles in the differentiation and function of TFH cells and in response to antibodies production. The serum IL-6 level was higher in both responder and non-responder groups compared to the control group, regardless of the presence of RBC autoantibodies (Fig. 4A). For serum IL-21 level, it was 2-fold higher in the responder group than the control group (Fig. 4B). The previous studies29,30 have demonstrated that the levels of both IL-21 and IL-6 are significantly associated with the frequency of TFH cells in the autoimmune diseases. In the present study, serum IL-21 level was strongly and positively correlated with the percentages of CXCR5+CD4+CD25−Foxp3−TFH cells in the responder group (Fig. 4C). Besides, there was a moderate and positive correlation between IL-21 level and CXCR5+CD4+CD25−Foxp3− cells in the non-responder group and no significant correlation was found in the control group (Fig. 4D,E). No predictive relationship between serum IL-6 level and this parameter in all the three groups was found (data not shown). Besides IL-21, IL-4 is another cytokine secreted by TFH cell and no difference was found among three groups (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Relative cytokine levels in the AIHA mouse model. (A) Levels of serum IL-6 in the responder, non-responder, and control groups in the 12 weeks after the first immunization. (B) Levels of serum IL-21 in these three groups in the 12 weeks after the first immunization. (C–E) Relationship of serum IL-21 levels and the percentage of CXCR5+CD4+CD25− TFH cells in these three groups, respectively. (F) Levels of serum IL-4 in these threegroups in the 12 weeks after the first immunization. Each plot represents one mouse in each group. This experiment was repeated three times with 6–7 mice in each group. Data shown were the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, no significance.

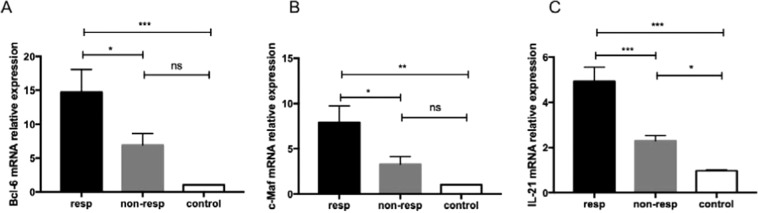

Bcl-6, c-Maf, and IL-21 mRNA expression in the AHIA mouse model

The transcriptional factors of Bcl-6 and c-Maf as well as cytokines IL-21 play crucial roles in the generation, differentiation, and function of TFH cells11. The mRNA expression of Bcl-6, c-Maf, and IL-21 was assessed in these three groups, respectively, which were notably higher in the responder group than the control group (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Expression of Bcl-6, c-Maf, and IL-21 mRNA in Tcells of the AIHA mouse model. (A) Levels of the relative expression of Bcl-6 mRNAof T cells from mice in the responder, non-responder, and control groups. (B) Levels of the relative expression of c-Maf mRNA of CD4+ T cells from these three groups. (C) Levels of the relative expression of IL-21 mRNA of CD4+T cells from these three groups. Experiments were repeated three times with 3–4 mice in each group. Data shown were the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

CXCR5+CD4+CD25−TFH cells play a positive role in the process of AIHA

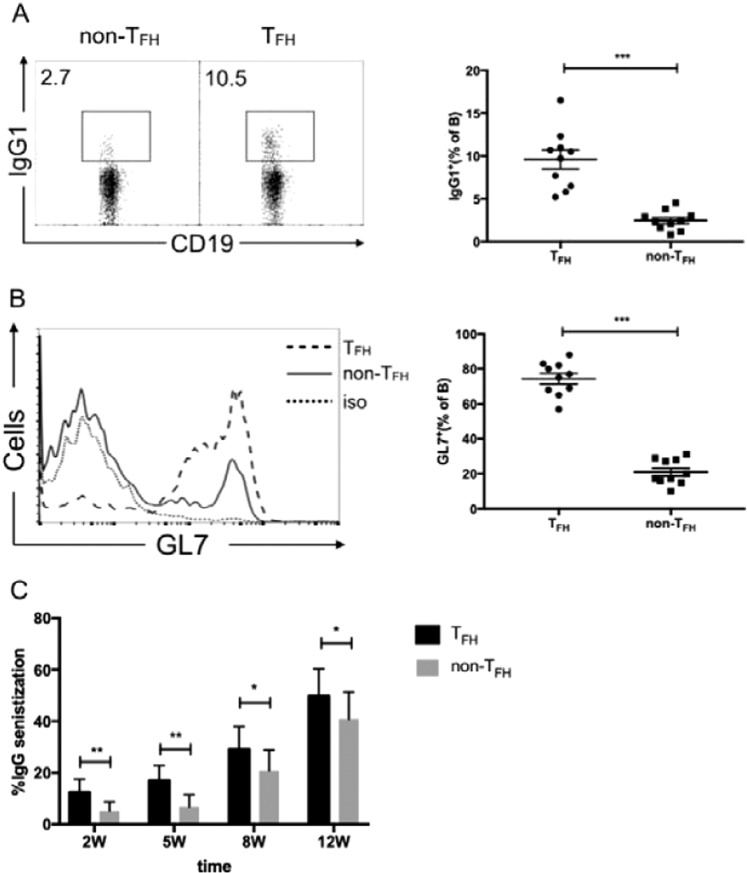

To study whether an increased proportion of CXCR5+CD4+CD25−TFH cells plays a role in the AIHA mouse model promotion activity, the in vitro B cell class switch recombination assays were investigated as described earlier31. CD4+CXCR5+CD25−TFH and CD4+CXCR5-CD25− T cells were sorted from the responder mice. These cells were cultured with CD19+ B cells (also isolated from the responder group) separately along with anti-IgM and anti-CD3. As expected, a significant increase in the promotion of class-switched IgG B cell by CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH cells compared to CD4+CXCR5−CD25−T cells was found (Fig. 6A). Next, expression of GL7 was examined as it is a sensitive marker for B cell activation in GC in these assays32. GL7 expression was increased 3- to 4-fold on B cells cultured with TFH cells than that cultured with CD4+CXCR5−CD25− T cells (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

The role of TFH cells in antibody productionand pathogenesis of AIHA. (A,B) CXCR5+CD4+CD25−TFH cells and CXCR5−CD4+CD25−Tcells (non-TFH) sorted from the responder group in week12 were cultured with CD19+ B cells from similarly immunized mice along with anti-CD3 and anti-IgM for six days. B cells were intracellularly stained for IgG1 (A) and surface stained for GL7 (B). Plots were pre-gated on CD19+ B cells. Each plot represented a single well. Data were from four independent experiments and the mean ± SEM were shown. ***p < 0.001. (C) The sorted CXCR5+CD4+CD25−TFH cells and CXCR5−CD4−CD25−T cells from the responder group were adoptively transferred into C57BL/6J mice one day before rat RBCs injection on a weekly basis. Level of IgG-specific autoantibodies on mouse RBCs was measured by flow cytometry and expressed as a percentage of background unstained cells on week 2, 5, 8, and 12. Data shown are of three independent experiments with five mice in each group.

Further, the TFH cell function was investigated in vivo. CD4+CXCR5+CD25−TFH or CD4+CXCR5−CD25−T cells from the responder group were adoptively transferred into naive C57BL/6J mice. The day after transfer, the mice were immunized with rat RBCs weekly for consecutive 12 weeks. As demonstrated in Fig. 6C,autoantibodies can be detected as early as the second week in the mice adoptively transferred TFH cells, whereas almost no autoantibody-positive red blood cells were detected in the mice transferred CD4+CXCR5−CD25− T cells. This elevated autoantibody level continued until 12 weeks.

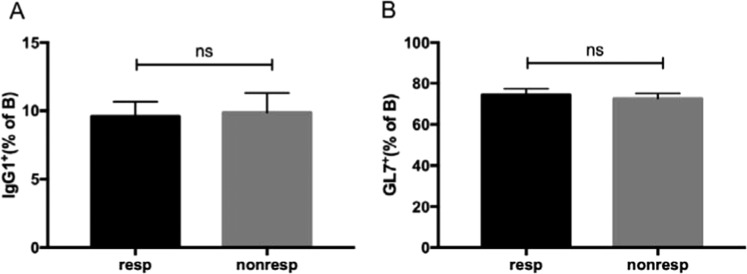

The promotion capacity of TFH cells between responder and non-responder groups

Furthermore, we compared the ability of TFH cells in the responder and non-responder groups by co-culturing the CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH cells from these two groups with CD19+ B cells along with anti-IgM and anti-CD3. As shown in Fig. 7, the expression of IgG1 and GL7 was similar in these two groups. Therefore, the promotion capacity of TFH cells was not significantly altered in the responder and non-responder groups (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

The equal functionality of TFH cells between the responder and non-responder. CXCR5+CD4+CD25−TFH cells sorted from the responder group and non-responder group in week 12 was cultured with CD19+ B cells from the responder group along with anti-CD3 and anti-IgM for six days. B cells were intracellularly stained for IgG1 and surface stained for GL7. The percentage of IgG1+(A) andGL7+ (B) cells was calculated in CD19+ B cells. Data were from three independent experiments and the mean ± SEM were shown. ns, no significance

Discussion

Here, the number of CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH cells were increased in autoantibody-positive AIHA mouse, resulting in a high ratio of TFH:TFR. Besides, the transcription level of Bcl-6 and c-Maf and serum IL-21 was elevated concomitantly. Furthermore, increased TFH cell activity was associated with the response against successive immunization with RBCs. Taken together, the results have significant implications on the role of TFH cells in the pathogenesis of AIHA.

AIHA is a severe and sometimes fatal disease. Although lots of knowledge is known about the generation of the destructive effects of pathogenic autoantibody in AIHA, there is still much to learn about the influencing factors of antibody generation. Several mechanisms have been studied to contribute to AIHA, including dysregulation of central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms, disruption of cytokine axes, and molecular mimicry between autoantigens and pathogens33–37.

Most studies of AIHA focused on the erythrocyte-specific autoreactive B cells, while T cell tolerance was considered to be a stopgap to autoimmunity38. In 2005, with Playfair and Marshall–Clarke model, Amina39 found the importance of CD25+regulatory T subsets in controlling AIHA in C57BL/6J mice. Treatment with anti-CD25 antibody prior to immunization increased the incidence of AIHA from 30% to 90%. Intriguingly, Richards AL40 demonstrated that Tregs are non-essential components of tolerance to the HOD RBC autoantigen. Different results were probably attributed to different mouse model and gene background. Besides, it is reported that T helper 17 (Th17) cells could affect the development of AIHA by enhancing the adaptive humoral responses in AIHA patients and mouse models41. But until now, limited reports have been found about the TFH and TFR cells in the pathogenesis of AIHA.

By weekly intraperitoneal injection of rat RBCs into mice, erythrocyte autoantibodies were detectable within 5–6 weeks after immunization. The number of erythrocyte autoantibodies peaked in 10–12 weeks and correlated with a significant increased level of reticulocytes and a shortened RBC lifespan. These index parameters demonstrated that our AIHA mouse model was well-constructed. According to our results, the number of CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH cells was significantly increased in the responder group than that in non-responder and control groups, with the incremental expression of ICOS and PD-1 correspondingly. Consistently, the transcription factors Bcl-6 and c-Maf were highly expressed in the responder group. Furthermore, the increasing TFH cell was moderately positively correlative associated with the anti-RBC IgG fluorescent units. It has been well known that interaction of TFH cells with B cells in the GC plays a fundamental role in the differentiation of plasma cells and production of high-affinity antibodies11. From the co-culture experiment, the CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH cells, rather than CD4+CXCR5−CD25− T cells, could promote B cell activation and antibody secretion. The adoptive transfer assay also confirmed the promotion function of TFH cells because of the earlier onset and increased level of erythrocyte autoantibody in the AIHA mice with adoptive transfer CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH cells. The function of TFH cells in the responder group was not altered compared to the non-responder group, despite the increased number of TFH cells.

Interactions of autocrine or paracrine cytokines with the receptors provide essential signals for the differentiation and function of TFH cells. Among them, IL-6 and IL-21 are most famous and well researched. IL-6, which is mainly secreted by the macrophage, can transiently induce the expression of the transcription factor Bcl-6 and IL-21, creating a positive feedback loop for enforcing the TFH cell fate16. Hence, the early programming of TFH cells is abated in the absence of IL-6. Although lack of IL-21 or IL-21 receptor did not affect the initial differentiation and expansion of TFH cells, those TFH cells failed to support GC reaction, leading to diminished levels of plasma cells and serum IgG. So, IL-21 is required for the TFH cell persistence and function17,28,42. Note that IL-21, the main and vital cytokine secreted by TFH cell, also influences B cell proliferation, survival and isotype switch, providing the bidirectional promotion role for both B cell and TFH cell15,43. According to our research, serum IL-6 and IL-21 levels were significantly higher in the responder group than the control, and, more remarkable, serum IL-21 level was strongly and positively correlated with the percentages of CXCR5+CD4+CD25−TFH cells in the responder group. Hence, the elevated IL-21 level was in favor of TFH cell proliferation and function, leading to the excessive GC response and antibody secretion. Apart from IL-21, IL-4 is another major help molecule produced by TFH cells to keep GC B cells alive and class switch recombination. However, no difference in serum IL-4 level was found between the responder and the control groups. Taken together, serum IL-21 level plays an important role in the TFH function of AIHA.

Newly reported Treg subset TFR cells could suppress TFH cells and GC B cells function by inhibiting cytokine IL-4/IL-21 production, preventing GL7 and B7-1 expression on B cells and limited class switch recombination22. Hence, we suspected that the enlarged TFH cell proportion and autoantibody secretion were caused by the TFR cells. In our research, the shrunken proportion of TFR cells in the responder group was discovered, as evidenced by decreased CD25+FoxP3+ subset among CD4+CXCR5+ cells. Therefore, the ratio of TFH:TFR was enlarged, leading to an imbalance of TFR and TFH cells. Moreover, the cell count was almost unchanged among three groups, indicating that TFR may not be the reason for the increased level of autoantibody in AIHA (Fig. 3E). Besides, no difference was found in the TFR function between responder and non-responder group in vitro (data not shown).

Some reports about CD4+CXCR5+CD25−TFR cells are considered as the terminally-differentiated TFR cells and retain the expression of Foxp3+ and suppressive molecules CTLA-444. Current studies suggest that down regulation of CD25 is a marker of TFR development. CD25+ TFR regulates the interactions at the T-B border and travels through the follicle, whereas CD25− TFR is responsible for direct suppression in the GC itself. Compared to CD25+ TFR, CD25− TFR cells shift its gene expression signature more similar to TFH cell, displaying a high level of Bcl-6, CXCR5, and PD-1 and a low level of Foxp3, Blimp1, PSGL145. In this study, the CD25− TFR was only 3-5% in the AIHA mouse (Fig. 3A). Similar to CD25+ TFR cell, the proportion of CD25− TFR cell was lower in responder and non-responder groups than that of control group. However, no difference was found in the absolute number among the three groups (data not shown). So, CD25− TFR may-be not a key point for erythrocyte autoantibody production in AIHA.

Up to now, plentiful research has demonstrated the key role of TFH and TFR cells in autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)46,47. ITP, similar to AIHA, is characterized by the increased platelet destruction by autoantibodies directed against platelet glycoproteins. It is reported that there is an increase in the proportion of circulating TFH cells and spleen TFH cells in the ITP patients, particularly in the anti-platelet antibody-positive patients. Plasma IL-21 level is also significantly increased in active ITP patients29,30,48. The above clinical findings are in accordance with our results. It should be highlighted that the frequency of circulating TFH cells returns to normal after therapy in the newly diagnosed ITP patients, whereas children who fall in chronic ITP have a persistent increase in both circulating TFH cells and serum IL-21 level48.

Limitations to this research are present. The role of TFH and TFR cells in differentiating anti-rat antibody vs. anti-mouse autoantibody responses need to be further studied. The situation of TFH and TFR cells in AIHA patients should also be studied thoroughly in the future. Overall, the studies for the first time have shed light on the important role of TFHcells in regulating anti-RBC autoantibody production during the pathogenesis process of AIHA. Although the role of the inflammatory environment in the increase in TFH frequency could not be completely excluded, our data strongly suggest that TFH cells participate in B cells differentiation and anti-RBC-antibody production. It is hoped that a greater understanding of TFH and TFR cells can result in promising therapeutic approaches against AIHA.

Materials and Methods

These studies were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines of Peking University Second Hospital. All study methods and experimental protocols were approved by Peking University Second Hospital.

Animals

C57BL/6J (B6) mice were purchased from the Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd and were housed in a specific pathogen-free barrier facility with restricted access. All care and handling of animals were performed according to the standard guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals in Peking University Second Hospital.

Immunization regimen for induction of AIHA

Rat RBCs were purchased from Zhengzhou Bestgene biotech company (Henan, China) and adjusted to 109 cell/mL. Female C57BL/6J mice between 8 and 10 weeks old were immunized weekly for 12 weeks through intraperitoneal injections with 2 × 108 rat RBCs in 200 μL RPMI.

Detection and measurement of auto- and alloantibodies

Blood samples (25 μL) by retro-orbital sinus bleeding were obtained on a weekly basis, five days after each immunization. IgG sensitization autoantibodies levels on the RBCs were determined by flow cytometry using FITC–conjugated anti–mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). For analysis of rat RBC-specific xenoantibodies, rat RBCs were incubated with diluted mouse plasma for one hour at 37 °C and after several washes, were stained with FITC-conjugated anti–mouse IgG as previously described39.

Mouse RBCs survival studies and reticulocyte counts

Mouse RBCs(1 × 109) were obtained from naive female C57BL/6J mice, labeled with PKH-26 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and injected by the tail-vein into control mice and those that had developed AIHA. Blood samples were obtained by retro-orbital sinus bleeding at the time points indicated after transfusion and the clearance of fluorescent RBCs was measured by flow cytometry as previously described49. Reticulocyte counts were performed using the Advia 120 Hematology System (Bayer, Tarrytown, NY).

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the spleen and the erythrocytes were depleted with the ACK lysis buffer. For surface staining, cells were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with fluorescent-labeled monoclonal Ab specific for mouse CD4, CD8, CXCR5, CD25, GL7, B220 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), PD-1 and ICOS (Invitrogen). For intracellular staining of Foxp3, cells stained with surface marker antibodies were fixed, permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and incubated with APC conjugated anti-mouse Foxp3 (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For intracellular staining of IgG1, cells were first fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) and then incubated with PE-conjugated anti-IgG1 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Corresponding isotype-matched control monoclonal antibodies were used in all flow cytometric staining procedures. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on FACSCalibur using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH or CD4+CXCR5−CD25− T cells from mice in the responder and non-responder group were sorted using FACSAria II sorter cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Serum from control mice and AIHA was used to test for the presence of cytokines IL-21, IL-6 and IL-4 with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Each step was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantitative mRNA Determinations

Total RNA was prepared from freshly isolated spleen CD4+T cells (5 × 106) with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and was used to make cDNA using random primers and the Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI). For quantitative real-time PCR, iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was performed on an iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The quantity of IL-21, Bcl-6 and c-Maf was normalized to the housekeeping gene Gapdh for each sample. The amplification conditions were as follows: 5 min at 95 °C for denaturation, and then 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 40 s. The fluorescence values were collected at 60 °C. The primer pairs used for PCR were as following: IL-21 Sense: 5-TCATCATTGACCTCGTGGCCC -3; Reverse: 5- ATCGTACTTCTCCACTTGCAATCCC -3; Bcl-6: Sense: 5-CACACCCGTCCATCATTGAA-3; Reverse: 5-TGTCCTCACGGTGCCTTTTT-3; c-Maf: Sense: 5-AGCAGTTGGTGACCATGTCG-3; Reverse: 5-TGGAGATCTCCTGCTTGAGG-3; Gapdh Sense: 5-CCTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTAT-3 Reverse: 5-AGAGTGGGAGTTGCTGTTGAAG-3.

Cell culture

For TFH stimulation assays, 2 × 104 CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH cells and CD4+CXCR5−CD25− T cells from mice of the responder group were plated with 5 × 104 CD19+ B cells (all purified from spleen of responder group) and 2 μg/mL soluble anti-CD3 (BD Biosciences) plus 5 μg/mL anti-IgM (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Cells were harvested and analyzed 6 days later.

Adoptive transfer studies

CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH or CD4+CXCR5−CD25− T cells from mice of the responder group were isolatedusing FACS Aria II sorter cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Approximately 2 × 104 sorted CD4+CXCR5+CD25− TFH or CD4+CXCR5−CD25− T cells in 0.1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was injected intravenously into 10-week-old female C57BL/6J recipient mice followed by weekly injections of rat RBCs one day later.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. One-way ANOVA analysis of variance was applied to determine whether an overall variation existed with statistical significance among the groups. Unpaired and paired Student’s t test was appropriately chosen to compare differences between two groups. The correlation between the two groups was analyzed by linear regression. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used for repeated measurement variables. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant from the National NaturalScience Foundation of China (No. 31700767). And there are no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

Yuhan Gao and Haiqiang Jin performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. Ding Nan, Weiwei Yu, Hongjun Hao, and Yongan Sun aided in the experiment and preparation of the manuscript. Ranran Qin, Jianhua Zhang, Ying Yang and Ruiqin Hou interpreted the data. Wenqin Tian and Yuhan Gao supervised the study and provided financial support. All authors revised the manuscript and approved its final version.

Data availability

Any data of this study were available to the public if necessary.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of any interest relevant to this topic. The corresponding authors had full access to the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yuhan Gao and Haiqiang Jin.

Contributor Information

Yuhan Gao, Email: gaoyuhan1228@163.com.

Wenqin Tian, Email: wenqintian@126.com.

References

- 1.Petz LD. Review: evaluation of patients with immune hemolysis. Immunohematology. 2004;20:167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salama A. Aquired immune hemolytic anemias. Ther Umsch. 2004;61:178–186. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930.61.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packman CH. The Clinical Pictures of Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia. Transfus Med Hemother. 2015;42:317–324. doi: 10.1159/000440656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domen RE. An overview of immune hemolytic anemias. Cleve Clin J Med. 1998;65:89–99. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.65.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhary RK, Das SS. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia: From lab to bedside. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2014;8:5–12. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.126681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lechner K, Jager U. How I treat autoimmune hemolytic anemias in adults. Blood. 2010;116:1831–1838. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-259325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynaud Q, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in auto-immune hemolytic anemia: A meta-analysis of 21 studies. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Go RS, Winters JL, Kay NE. How I treat autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2017;129:2971–2979. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-693689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howie HL, Hudson KE. Murine models of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2018;25:473–481. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazilleau N, Mark L, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Follicular helper T cells: lineage and location. Immunity. 2009;30:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T. cells (TFH). Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma CS, Deenick EK, Batten M, Tangye SG. The origins, function, and regulation of T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1241–1253. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crotty S. T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity. 2014;41:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurieva RI, et al. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linterman MA, et al. IL-21 acts directly on B cells to regulate Bcl-6 expression and germinal center responses. J Exp Med. 2010;207:353–363. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi YS, Eto D, Yang JA, Lao C, Crotty S. Cutting edge: STAT1 is required for IL-6-mediated Bcl6 induction for early follicular helper cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2013;190:3049–3053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasheed MA, et al. Interleukin-21 is a critical cytokine for the generation of virus-specific long-lived plasma cells. J Virol. 2013;87:7737–7746. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00063-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breitfeld D, et al. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1545–1552. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinhardt RL, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Cytokine-secreting follicular T cells shape the antibody repertoire. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma CS, Deenick EK. Human T follicular helper (Tfh) cells and disease. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:64–71. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sage PT, Sharpe AH. T follicular regulatory cells. Immunol Rev. 2016;271:246–259. doi: 10.1111/imr.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sage PT, Sharpe AH. T follicular regulatory cells in the regulation of B cell responses. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong Y, Tong J, Wang S. Are Follicular Regulatory T Cells Involved in Autoimmune Diseases? Front Immunol. 2017;8:1790. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui Y, et al. The changes of circulating follicular regulatory T cells and follicular T helper cells in children immune thrombocytopenia. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2014;35:980–984. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandya JM, et al. Circulating T helper and T regulatory subsets in untreated early rheumatoid arthritis and healthy control subjects. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100:823–833. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5A0116-025R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Playfair JH, Marshall-Clarke S. Induction of red cell autoantibodies in normal mice. Nat New Biol. 1973;243:213–214. doi: 10.1038/newbio243213a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox KO, Keast D. Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia induced in mice immunized with rat erythrocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1974;17:319–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eto D, et al. IL-21 and IL-6 are critical for different aspects of B cell immunity and redundantly induce optimal follicular helper CD4 T cell (Tfh) differentiation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Audia S, et al. Splenic TFH expansion participates in B-cell differentiation and antiplatelet-antibody production during immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2014;124:2858–2866. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-563445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie J, et al. Changes in follicular helper T cells in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura patients. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11:220–229. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.10178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sage PT, Tan CL, Freeman GJ, Haigis M, Sharpe AH. Defective TFH Cell Function and Increased TFR Cells Contribute to Defective Antibody Production in Aging. Cell Rep. 2015;12:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sage PT, Alvarez D, Godec J, von Andrian UH, Sharpe AH. Circulating T follicular regulatory and helper cells have memory-like properties. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:5191–5204. doi: 10.1172/JCI76861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell PJ, Cunningham J, Dunkley M, Wilkinson NM. The role of suppressor T cells in the expression of autoimmune haemolytic anaemia in NZB mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;45:496–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakami M, et al. Oral administration of lipopolysaccharides activates B-1 cells in the peritoneal cavity and lamina propria of the gut and induces autoimmune symptoms in an autoantibody transgenic mouse. J Exp Med. 1994;180:111–121. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Sa Oliveira GG, et al. Diverse antigen specificity of erythrocyte-reactive monoclonal autoantibodies from NZB mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:313–320. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall AM, et al. Deletion of the dominant autoantigen in NZB mice with autoimmune hemolytic anemia: effects on autoantibody and T-helper responses. Blood. 2007;110:4511–4517. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iuchi Y, et al. Implication of oxidative stress as a cause of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in NZB mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:935–944. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barker RN, Shen CR, Elson CJ. T-cell specificity in murine autoimmune haemolytic anaemia induced by rat red blood cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;129:208–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mqadmi A, Zheng X, Yazdanbakhsh K. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control induction of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2005;105:3746–3748. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richards AL, Kapp LM, Wang X, Howie HL, Hudson KE. Regulatory T Cells Are Dispensable for Tolerance to RBC Antigens. Front Immunol. 2016;7:348. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu L, et al. Critical role of Th17 cells in development of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Exp Hematol. 2012;40:994–1004 e1004. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spolski R, Leonard WJ. IL-21 and T follicular helper cells. Int Immunol. 2010;22:7–12. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryant VL, et al. Cytokine-mediated regulation of human B cell differentiation into Ig-secreting cells: predominant role of IL-21 produced by CXCR5+ T follicular helper cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:8180–8190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wing JB, Tekguc M, Sakaguchi S. Control of Germinal Center Responses by T-Follicular Regulatory Cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1910. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wing JB, et al. A distinct subpopulation of CD25(−) T-follicular regulatory cells localizes in the germinal centers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S. 2017;A114:E6400–E6409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705551114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakayamada S, Tanaka Y. T follicular helper (Tfh) cells in autoimmune diseases. Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi. 2016;39:1–7. doi: 10.2177/jsci.39.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu W, et al. Deficiency in T follicular regulatory cells promotes autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2018;215:815–825. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao X, et al. Differences in frequency and regulation of T follicular helper cells between newly diagnosed and chronic pediatric immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2016;61:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yazdanbakhsh K, Kang S, Tamasauskas D, Sung D, Scaradavou A. Complement receptor 1 inhibitors for prevention of immune-mediated red cell destruction: potential use in transfusion therapy. Blood. 2003;101:5046–5052. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any data of this study were available to the public if necessary.