Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients have poor prognosis and poor response to treatment. This is largely due to PDAC being associated with a dense and active stroma and tumor fibrosis (desmoplasia). Desmoplasia is characterized by excessive degradation and formation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) generating collagen fragments that are released into circulation. We evaluated the association of specific collagen fragments measured in pre-treatment serum with outcome in patients with PDAC. Matrix metalloprotease (MMP)-degraded type I collagen (C1M), type III collagen (C3M), type IV collagen (C4M) and a pro-peptide of type III collagen (PRO-C3) were measured by ELISA in pre-treatment serum from a randomized phase 3 clinical trial of patients with stage III/IV PDAC treated with 5-fluorouracil based therapy (n = 176). The collagen fragments were evaluated for their correlation (r, Spearman) with serum CA19-9 and for their association with overall survival (OS) based on Cox-regression analyses. In this phase 3 PDAC trial, pre-treatment serum collagen fragment levels were above the reference range for 67%-98% of patients, with median values in PDAC approximately two-fold higher than reference levels. Collagen fragment levels did not correlate with CA19-9 (r = 0.049–0.141, p = ns). On a continuous basis, higher levels of all collagen fragments were associated with significantly shorter OS. When evaluating degradation (C3M) and formation (PRO-C3) of type III collagen further, higher PRO-C3 was associated with poor OS (>25th percentile cut-point, HR = 2.01, 95%CI = 1.33–3.05) and higher C3M/PRO-C3 ratio was associated with improved OS (>25th percentile cut-point, HR = 0.53, 95%CI = 0.34–0.80). When adjusting for CA19–9 and clinical covariates, PRO-C3 remained significant (HR = 1.65, 95%CI = 1.09–2.48). In conclusion, collagen remodeling quantified in pre-treatment serum as a surrogate measure of desmoplasia was significantly associated with OS in a phase 3 clinical PDAC trial, supporting the link between desmoplasia, tumorigenesis, and response to treatment. If validated, these biomarkers may have prognostic and/or predictive potential in future PDAC trials.

Subject terms: Tumour biomarkers, Post-translational modifications

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is one of the most lethal types of cancer with an overall 5-year survival rate of 8% dropping to 3% in the metastatic setting1. At time of diagnosis, approximately 10% of PC patients have tumors that are potentially curable with resection, and 50% have metastatic disease. In 2017, in the United States alone, 55,440 new cases and 44,330 deaths were recorded. It has been projected that PC will become the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States in the next decade, hence PC is a clear exception from the general trend of improvement in survival rates for patients with other cancers1,2.

Not only is PC diagnosed late, but patients with advanced PC also respond poorly to chemo- and targeted-therapies3,4. Currently, besides imaging (computed tomography), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), an antigen released by pancreatic cancer cells and measured in serum, is the only recommended biomarker for predicting and monitoring outcome in the PC setting5. Taken together, the grim PDAC outcome emphasizes the need not only for innovative drug development efforts, but also for the development of biomarkers that can be used for stratifying PC patients and predicting their outcome and likelihood of response to treatment.

Pancreatic ducal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most common form of PC and accounts for more than 80% of cases. PDAC is the most stromal cancer type across all tumor indications, characterized by an extremely dense and desmoplastic (fibrotic) tumor microenvironment6,7. The desmoplastic reaction is highly associated with therapy resistance and tumorigenesis, thus accounting for the lack of satisfactory outcomes for PDAC patients8,9.

Desmoplasia is characterized by an altered remodeling of the collagenous extracellular matrix (ECM), which is the non-cellular component of tissue. While the ECM turnover in healthy tissue is maintained in a delicate homeostatic state between ECM/collagen formation and degradation, this homeostasis is lost in the tumor tissue10–13. Upregulation of the production and assembly of collagens, i.e. the formation of a fibrous connective tissue, is driven by proliferation and activation of myofibroblasts and myofibroblast-like stellate cells14,15. An associated collagen degradation is concomitantly observed, and is driven by a highly proteolytically-active tumor microenvironment, in which the matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) play a key role in degrading collagens16,17.

The interstitial matrix-associated type I collagen, type III collagen, and the basement membrane-associated type IV collagen have all been found upregulated in the primary tumors and metastatic lesions of PDAC, and are associated with poor outcome and pro-tumorigenic events7,18–21. Type IV collagen is a network forming collagen that supports the epithelia/endothelia whereas type I and type III collagen are fibrillar collagens part of the underlying stromal interstitial matrix. While tumor cell invasion and angiogenesis are associated with remodeling and degradation of type IV collagen, the synthesis, deposition, remodeling and degradation of the fibrillar collagens is more directly linked to fibroblast activity21–25.

A pilot study has evaluted the biomarker potential of specific MMP-derived fragments of type I (C1M), type III (C3M), and type IV (C4M) collagen as surrogate measures of desmoplasia and ECM remodeling, and found that all these fragments were elevated in serum from patients with PDAC compared to healthy controls26. Based on these findings, and the importance of desmoplasia in PDAC, we hypothesized that C1M, C3M, C4M, as well as PRO-C3, a biomarker derived from the pro-peptide of type III collagen, were predictive of outcome in the PDAC setting.

The aim of this study was to evalute how levels of specific collagen fragments (C1M, C3M, C4M, PRO-C3), quantified in pre-treatment serum, were associated with overall survival (OS) in a randomized phase 3 clinical trial of patients with advanced unresectable PDAC. The association between the collagen markers and CA19-9, the gold-standard PDAC serum biomarker, and outcome was also evaluated.

Methods

Patients and study design

The present study includes 176 patients with advanced unresectable PDAC that were enrolled in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial. One arm received octreotide (somatostatin, a somatotrophin-release inhibiting factor analogue) and continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and another arm received placebo and 5-FU27.

Briefly, patient inclusion criteria included (1) at least 18 years of age; (2) measurable or evaluable, stage III or IV, pathologically, histologically, or cytologically confirmed unresectable adenocarcinoma of the exocrine pancreas; and (3) no prior chemotherapy, radiation, or hormonal therapy28. The trial was powered to achieve 330 evaluable patients (165 per arm) with planned randomization of 412 patients (206 per arm) to detect an increase in 1-year survival rate from 10% in the 5-FU + placebo group to 20% in the 5-FU + octreotide group with a power of 0.85. The primary objective of this trial was overall survival (OS); secondary objectives were progression-free survival (PFS), clinical benefit, tolerability of octreotide, and objective response rate. Treatment after randomization was octreotide (160 mg intramuscular initiation, every 2 weeks for four injections and then every 4 weeks until disease progression) vs. placebo; 5-FU was given immediately following the first octreotide injection, by continuous intravenous infusion at a total daily dose of 225 mg/m2, for 8 weeks, followed by a 7-day rest period, and then, 5-FU was repeated until disease progression. The trial was stratified for gender, Karnofsky performance status (KPS, 70–100% vs. 50–60%), and stage of disease (III vs. IV).

The interim efficacy analysis of this clinical trial reported that the median OS time in the octreotide arm was 22.6 weeks (95%CI: 18.1–27.7) vs. 21.6 weeks in the placebo arm (95%CI: 17.9–28.3); this was not a significant difference (P = 0.649) in OS between the two arms (27). There was one complete (stage III, in octreotide arm) and two partial remissions (both in stage IV; one in octreotide arm and one in placebo arm). Since there was no efficacy difference in the two arms of this trial, it is optimal for biomarker discovery and validation. This same cohort had previously been used to report a significant association between higher inflammatory serum biomarkers (ferritin and C-reative protein, CRP) and shorter OS28.

Serum biomarker measurements

Biomarker levels were measured in pre-treatment serum samples. C1M (MMP-degraded type I collagen, originally described by Leeming et al.29), C3M (MMP-degraded type 3 collagen, originally described by Veidal et al.30), C4M (MMP-degraded type IV collagen, originally described by Veidal et al.31) and PRO-C3 (N-terminal pro-peptide of type III collagen, originally described by Nielsen et al.32) were quantified by individual competitive enzyme-linked immune sorbent associated assays (ELISAs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nordic Bioscience, Herlev, Denmark). The normal reference range (mean with 95%CI) for the collagen markers were pre-defined from a population of 617 healthy men and women ranging from 22 to 86 years of age33. The upper limit of the reference range was 28.4 ng/ml for C1M, 10.3 ng/ml for C3M, 19.3 ng/ml for C4M and 8.7 ng/ml for PRO-C3. Biomarker values below/above the detection limit were assigned the lower/upper limit of detection value for each respective assay.

Statistical analysis

The serum collagen fragments (C1M, C3M, C4M and PRO-C3) were analyzed for an association with OS by use of univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards modeling. Biomarkers (variables) were evaluated both on a continuous and categorical scale, the latter by dichotomizing the variables by separation at the 25th percentile cut-point. The dichotomized variables were also evaluated by Kaplan-Meier survival estimates (OS curves). Correlations between serum collagen fragments and CA19-9 were evaluated by calculating the Spearman rank correlation coefficients. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Signed informed consent to participate in the present study was obtained from all patients before sample collection. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at the Pennsylvania State University Hershey Medical Center and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki28.

Results

Patient demographics

The demographics and patient characteristics are shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

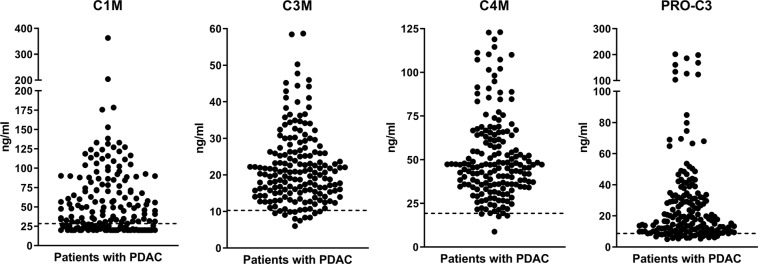

Levels of collagen fragments in serum from patients with PDAC

An overview of the distribution of the collagen fragments C1M, C3M, C4M and PRO-C3 in pre-treatment serum samples from 176 patients with advanced PDAC is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Overall, most of patients presented with biomarker levels above the reference range and with median values in PDAC approximately two-fold higher than the reference range.

Table 1.

Overview of collagen fragment biomarker levels in pre-treatment serum from patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).

| C1M | C3M | C4M | PRO-C3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum, ng/ml | 20.0 | 6.0 | 8.8 | 5.0 |

| 25% Percentile, ng/ml | 23.4 | 15.1 | 35.7 | 10.4 |

| Median, ng/ml | 44.7 | 20.5 | 46.9 | 17.7 |

| 75% Percentile, ng/ml | 84.4 | 26.3 | 64.0 | 33.1 |

| Maximum, ng/ml | 362.9 | 58.7 | 123.0 | 201.8 |

| % above reference range | 67% | 93% | 98% | 86% |

Figure 1.

Levels of collagen fragments (C1M, C3M, C4M, PRO-C3) in pre-treatment serum from 176 patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). C1M measures MMP-degraded type I collagen, C3M measures MMP-degraded type 3 collagen, C4M measures MMP-degraded type IV collagen, and PRO-C3 measures the N-terminal pro-peptide of type III collagen. The dotted line represents the upper limit of the normal reference range (defined as mean with 95%CI) from a population of 617 healthy men and women ranging from 22 to 86 years of age33.

Correlations between collagen fragments and CA19-9

Table 2 shows the Spearman rank correlation coefficients (r) between the collagen markers (C1M, C3M, C4M and PRO-C3) and CA19-9. While all collagen fragments correlated with each other (r = 0.462–0.897, p < 0.0001), no correlation was seen between any of the collagen markers and CA19-9 (r = 0.049–0.141, p = 0.065–0.521). This indicates that the collagen fragments represent similar pathological events, and that these are distinct from the pathological events linked to CA19-9.

Table 2.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients (r) between the collagen markers (C1M, C3M, C4M and PRO-C3) and CA19-9.

| C3M, ng/ml | C4M, ng/ml | PRO-C3, ng/ml | CA 19-9, U/ml | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C1M, ng/ml |

r p-value |

0.679<0.0001 | 0.636<0.0001 | 0.485<0.0001 | 0.0840.2751 |

|

C3M, ng/ml |

r p-value |

— — |

0.897<0.0001 | 0.462<0.0001 | 0.0490.5213 |

|

C4M, ng/ml |

r p-value |

— — |

0.516<0.0001 | 0.1150.1297 | |

|

PRO-C3, ng/ml |

r p-value |

— — |

0.1410.0649 |

Association between collagen fragments in serum and clinical demographics and overall survival (OS) outcome

First, when evaluating the association between stage of disease and Karnofsky performance status (KPS) and collagen fragments, serum C1M and PRO-C3 were significantly higher in patients with Stage IV vs Stage II and III disease (Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, serum C1M, C3M, and PRO-C3 were significantly higher in patients with a KPS of 1 vs 0.

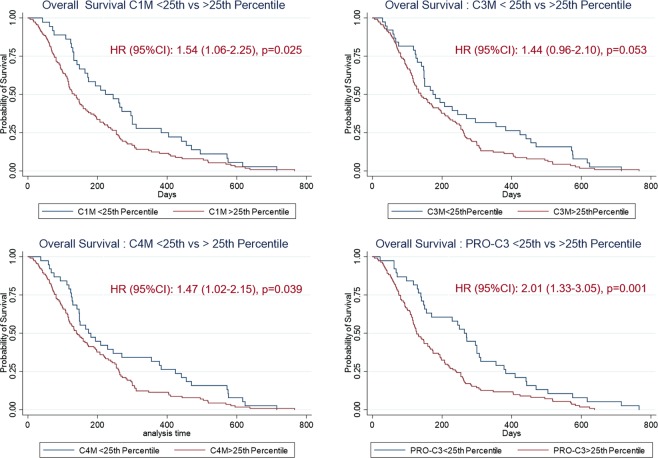

When evaluated by univariate analysis (Table 3), C3M, C4M and PRO-C3 predicted for significantly shorter OS when evaluated on a continuous scale (p = 0.004–0.037), while C1M was only borderline significant (p = 0.056). In contrast, the C3M/PRO-C3 ratio predicted for improved OS (p = 0.035). When evaluating the four collagen fragments individually on a categorical scale by dichotomization at the 25th percentile cut-point, patients above the 25th percentile cut-point had shorter OS. Patients had an approximately 1.5-fold increased risk of dying if presenting with high levels of C1M (HR = 1.54, p = 0.025), C3M (HR = 1.44, p = 0.053) and C4M (HR = 1.47, p = 0.039), respectively. Patients with high levels of PRO-C3 had a 2-fold increased risk of dying (HR = 2.01, p = 0.001). Again, high C3M/PRO-C3 predicted for a survival benefit with ratio-high patients having a 47% reduced risk of dying (HR = 0.53, p = 0.002).

Table 3.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards modelling for evaluating the association between serum collagen fragments (C1M, C3M, C4M and PRO-C3) and overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced unresectable PDAC.

| Biomarker | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous scale (n, events/total) | |||

| C1M (16/149) | 1.002 | 0.999–1.005 | 0.056 |

| C3M (17/152) | 1.019 | 1.004–1.036 | 0.015 |

| C4M (17/152) | 1.007 | 1.0004–1.013 | 0.037 |

| PRO-C3 (16/149) | 1.001 | 1.006–1.014 | 0.004 |

| C3M/PRO-C3 (ratio) (16/149) | 0.770 | 0.610–0.982 | 0.035 |

| Categorical scale, ≤25th vs. >25th percentile | |||

| C1M | 1.54 | 1.06–2.25 | 0.025 |

| C3M | 1.44 | 0.96–2.1 | 0.053 |

| C4M | 1.47 | 1.02–2.15 | 0.039 |

| PRO-C3 | 2.01 | 1.33–3.05 | 0.001 |

| C3M/PRO-C3 | 0.53 | 0.35–0.80 | 0.002 |

Next, an association between the collagen fragments and OS was evaluated by Kaplan-Meier plots using the 25th percentile cut-point (Fig. 2). Overall, high levels of serum collagen fragments were associated with shorter OS. Median OS for patients with high vs low (>25% vs ≤25%) C1M was 133 days vs. 223 days; high vs low C3M was 139 days vs. 174 days; high vs low C4M was 139 days vs. 174 days, and high vs low PRO-C3 was 127 days vs. 264 days. When evaluating the C3M/PRO-C3 ratio, median OS for patients with a high C3M/PRO-C3 ratio was 172 days vs 109 days for patients with a low C3M/PRO-C3 ratio (not shown).

Figure 2.

Probability of overall survival (OS) evaluated by Kaplan-Meier plots of patients with PDAC after dichotomizing the individual collagen biomarkers (C1M, C3M, C4M, PRO-C3) at the 25th percentile cut-point. Hazard Ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (95%CI) for patients with biomarker levels >25th percentile shown on each graph.

Lastly, multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate the predictive value of the serum collagen fragments and clinical demographics with OS (Table 4). The serum collagen fragments were analyzed by dichotomization at the 25th percentile cut-point, and clinical demographics included age (continuous), stage (categorical) and Karnofsky performance status (KPS) (categorical). In this multivariate analysis (Table 4) (adjusted for serum CA19-9), only serum PRO-C3 (HR 1.65, p = 0.018), and stage (HR 1.33, p = 0.03) remained significant. Age, KPS, and the remaining serum collagen fragments (C1M, C3M, and C4M) were not significant.

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards modelling adjusted for serum CA19-9 for evaluating the predictive value of serum collagen fragments (C1M, C3M, C4M and PRO-C3) and clinical demographics with overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced unresectable PDAC.

| Biomarker | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (continuous) | 1.003 | 0.986–1.021 | 0.704 |

| Stage (II + III vs IV) | 1.33 | 1.03–1.71 | 0.030 |

| KPS (0 vs 1) | 0.79 | 0.44–1.40 | 0.418 |

| C1M, 25th percentile | 1.03 | 0.64–1.67 | 0.893 |

| C3M, 25th percentile | 1.08 | 0.47–2.49 | 0.856 |

| C4M, 25th percentile | 1.27 | 0.57–2.86 | 0.558 |

| PRO-C3, 25th percentile | 1.65 | 1.09–2.48 | 0.018 |

Discussion

PDAC is the most stroma-rich cancer type characterized by severe desmoplasia and ongoing ECM remodeling, both in the primary tumor and metastatic lesions7. Alterations in the tumor ECM not only associates with aggressive disease and impedes access/activity of anti-tumor therapy, but also generates circulating collagen fragments with pathologic fingerprints. In this study we measured such fingerprints in association with OS outcome.

The present results show that specific collagen peptide fingerprints that reflect collagen synthesis (PRO-C3) and collagen degradation (C1M, C3M, C4M) are highly elevated in patients with advanced unresectable PDAC compared to the healthy reference range, have a relatively broad dynamic range and associate with outcome when measured in serum prior to treatment with 5-FU-based therapy. These findings support what has been reported with the same markers in diagnostic (case-control) studies of lung cancer, breast cancer and ovarian cancer as well as prognostic studies of both metastatic breast cancer patients treated with letrozole or trastuzumab, and metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab34–37. Importantly, this study also confirms previous findings showing that MMP-mediated collagen turnover measured in serum by C1M, C3M and C4M is elevated in PDAC compared to healthy controls, as well as data showing prognostic value of PRO-C3 measured in PC patients26,38.

Of the four collagen markers tested, PRO-C3 and the C3M/PRO-C3 ratio performed best in predicting OS outcome in PDAC. PRO-C3 measures the pro-peptide that is released when type III collagen assembles in the tissue. Type III collagen is synthesized by activated fibroblasts and is a major component of the desmoplastic reaction and ECM accumulation in the tumor. C3M is a measure of type III collagen degradation, therefore the C3M/PRO-C3 ratio can be interpreted to reflect a reduced net fibrotic activity: high collagen degradation (C3M) with low collagen accumulation (PRO-C3). Clearly, this supports the notion that by measuring the surrogates of the desmoplastic reaction and altered turnover of the interstitial collagens (e.g. type III collagen), it is possible to identify patients with worsened prognosis39. In addition, PRO-C3 did not associate with CA19-9, indicating that PRO-C3 reflects a different underlying biology than the current gold standard PDAC serum biomarker (CA19-9), and hence may add additional value when evaluated to a greater extent in future clinical trials as they are produced by different cell types in the tumor microenvironment, i.e. cancer cells (CA19-9) and cancer associated fibroblasts (PRO-C3).

Previous findings have shown that collagen types I, III, and IV are concomitantly overexpressed together with hyaluronan (HA, a high-molecular-mass polysaccharide found in the ECM), predicting for poor prognosis and poor response to chemotherapy in PC7,40. This ultimately led to development of a recombinant pegylated hyaluronidase enzyme (PEGPH20, targeting HA), which would potentially increase drug uptake of chemotherapy41. A randomized phase II study (HALO-202) of PEGH20 combined with gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel in stage 4 PDAC patients showed promising results of adding PEGPH20 to chemotherapy in a subgroup of patients with HA-positive tumor biopsies42. Interestingly, preliminary data based on retrospective analysis of HALO-202 also suggested that the C3M/PRO-C3 ratio was able to identify a subgroup of patients with better benefit of PEGPH2043. Together these findings suggest not only prognostic potential of C3M and PRO-C3, but also the ability to predict the likelihood of responding to a given combination of modalities. With the next wave of stroma/ECM-targeting therapy for PDAC on its way, inclusion of non-invasive biomarkers to identify specific subtypes of PDAC with ongoing desmoplasia is an important step forward44–46. However, to include the present biomarkers in clinical trial decision-making, the present study needs to be validated in larger, well characterized clinical cohorts, since the present result is limited by a relatively small sample size with limited available clinical information and is a retrospective biomarker analysis for predicting outcome.

In conclusion, this study shows that collagen remodeling biomarkers measured in pre-treatment serum are highly elevated and associated with OS in PDAC patients, supporting the link between the desmoplastic reaction, tumorigenesis, prognosis, and response to treatment. Of the four biomarkers evaluated, PRO-C3, a biomarker of type III collagen formation, appeared to provide the best prognostic value, independent of CA19-9. In summary, these results aid in the understanding of ECM turnover (formation and degradation of different collagens) as an important component in tumor progression and/or response to treatment. If validated in larger clinical cohorts, these collagen biomarkers may have potential as prognostic and/or predictive biomarkers in the PDAC setting.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Danish Research Foundation for supporting the biomarker measurements in this study.

Author contributions

N.W., S.M.A., K.L., M.A.K. and A.L. did the conceptualization; N.W. did the biomarker measurements and wrote the original first draft; All authors took part in analysis and interpretation of data and read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

Nicholas Willumsen and Morten A. Karsdal have declared financial competing interest from employment at Nordic Bioscience involved in biomarker discovery and development. All remaining authors have declared no financial conflicts of interest. None of the authors have non-financial competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-56268-3.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teague, A., Lim, K.-H. & Wang-Gillam, A. Advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a review of current treatment strategies and developing therapies. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 7, 68–84 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Adamska, A., Domenichini, A. & Falasca, M. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: Current and Evolving Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Balaban EP, et al. Locally advanced, unresectable pancreatic cancer: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:2654–2667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feig C, et al. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;18:4266–4276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whatcott CJ, et al. Desmoplasia in primary tumors and metastatic lesions of pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:3561–3568. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon A, et al. Desmoplasia in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: insight into pathological function and therapeutic potential. Genes Cancer. 2018;9:78–86. doi: 10.18632/genesandcancer.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg A, Mahalingam D. Immunotherapy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma-overcoming barriers to response. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2018;9:143–159. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2018.01.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J.Cell Biol. 2012;196:395–406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karsdal MA, et al. Extracellular matrix remodeling: the common denominator in connective tissue diseases. Possibilities for evaluation and current understanding of the matrix as more than a passive architecture, but a key player in tissue failure. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2013;11:70–92. doi: 10.1089/adt.2012.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:786–801. doi: 10.1038/nrm3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filipe EC, Chitty JL, Cox TR. Charting the unexplored extracellular matrix in cancer. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2018;99:58–76. doi: 10.1111/iep.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yen TWF, et al. Myofibroblasts are responsible for the desmoplastic reaction surrounding human pancreatic carcinomas. Surgery. 2002;131:129–34. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.119192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apte MV, et al. Desmoplastic Reaction in Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas. 2004;29:179–187. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shields MA, ngi-Garimella S, Redig AJ, Munshi HG, Dangi-Garimella S. Biochemical role of the collagen-rich tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer progression. Biochem.J. 2012;441:541–552. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong T, et al. Type I Collagen Promotes the Malignant Phenotype of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:7427–7437. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imamura T, et al. Quantitative analysis of collagen and collagen subtypes I, III, and V in human pancreatic cancer, tumor-associated chronic pancreatitis, and alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1995;11:357–64. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199511000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menke, A. et al. Down-Regulation of E-Cadherin Gene Expression by Collagen Type I and Type III in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines. Biochemistry61, 3508–3517 (2001). [PubMed]

- 21.Öhlund D, et al. Type IV collagen stimulates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, migration, and inhibits apoptosis through an autocrine loop. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gascard P, Tlsty TD. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts: Orchestrating the composition of malignancy. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1002–1019. doi: 10.1101/gad.279737.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Gialeli C, Karamanos NK. Extracellular matrix structure. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016;97:4–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat.Rev.Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:582–598. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willumsen, N. et al. Extracellular matrix specific protein fingerprints measured in serum can separate pancreatic cancer patients from healthy controls. BMC Cancer 13, 554 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Roy A, et al. Phase 3 trial of SMS 201-995 pa LAR (SMS PA LAR) and continuous infusion 5FU in unresectable stage II, III, and IV pancreatic cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1998;17:257. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alkhateeb A, et al. Elevation in multiple serum inflammatory biomarkers predicts survival of pancreatic cancer patients with inoperable disease. J. Gastrointest. Cancer. 2014;45:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s12029-013-9564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leeming D, et al. A novel marker for assessment of liver matrix remodeling: an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detecting a MMP generated type I collagen neo-epitope (C1M) Biomarkers. 2011;16:616–628. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2011.620628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barascuk N, et al. A novel assay for extracellular matrix remodeling associated with liver fibrosis: An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for a MMP-9 proteolytically revealed neo-epitope of type III collagen. Clin. Biochem. 2010;43:899–904. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veidal SS, et al. Assessment of proteolytic degradation of the basement membrane: a fragment of type IV collagen as a biochemical marker for liver fibrosis. Fibrogenesis.Tissue Repair. 2011;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielsen MJ, et al. The neo-epitope specific PRO-C3 ELISA measures true formation of type III collagen associated with liver and muscle parameters. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2013;5:303–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kehlet SN, et al. Age-related collagen turnover of the interstitial matrix and basement membrane: Implications of age- and sex-dependent remodeling of the extracellular matrix. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Willumsen Nicholas, Bager Cecilie L., Leeming Diana J., Smith Victoria, Christiansen Claus, Karsdal Morten A., Dornan David, Bay-Jensen Anne-Christine. Serum biomarkers reflecting specific tumor tissue remodeling processes are valuable diagnostic tools for lung cancer. Cancer Medicine. 2014;3(5):1136–1145. doi: 10.1002/cam4.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bager C.L., Willumsen N., Leeming D.J., Smith V., Karsdal M.A., Dornan D., Bay-Jensen A.C. Collagen degradation products measured in serum can separate ovarian and breast cancer patients from healthy controls: A preliminary study. Cancer Biomarkers. 2015;15(6):783–788. doi: 10.3233/CBM-150520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipton A, et al. High turnover of extracellular matrix reflected by specific protein fragments measured in serum is associated with poor outcomes in two metastatic breast cancer cohorts. Int. J. Cancer. 2018;143:3027–3034. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen C, et al. Non-invasive biomarkers derived from the extracellular matrix associate with response to immune checkpoint blockade (anti- CTLA-4) in metastatic melanoma patients. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2018;6:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0474-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen, I. et al. Clinical value of serum hyaluronan and propeptide of type III collagen in patients with pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Cancer (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Nissen NI, Karsdal M, Willumsen N. Collagens and Cancer associated fibroblasts in the reactive stroma and its relation to Cancer biology. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38:115. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Provenzano PP, et al. Enzymatic Targeting of the Stroma Ablates Physical Barriers to Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong, K. M., Horton, K. J., Coveler, A. L., Hingorani, S. R. & Harris, W. P. Targeting the Tumor Stroma: the Biology and Clinical Development of Pegylated Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase (PEGPH20). Curr. Oncol. Rep. 19 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Hingorani SR, et al. HALO 202: Randomized phase II Study of PEGPH20 Plus Nab-Paclitaxel/Gemcitabine Versus Nab-Paclitaxel/Gemcitabine in Patients With Untreated, Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:359–366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.9564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Song, Willumsen Nicholas, Bager Cecilie, Karsdal Morten A, Chondros Dimitrios, Taverna Darin. Extracellular matrix (ECM) circulating peptide biomarkers as potential predictors of survival in patients (pts) with untreated metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (mPDA) receiving pegvorhyaluronidase alfa (PEGPH20), nab-paclitaxel (A), and gemcitabine (G) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(15_suppl):12030–12030. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.12030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang H, Brekken RA. The next wave of stroma-targeting therapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79:328–330. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elahi-Gedwillo KY, Carlson M, Zettervall J, Provenzano PP. Antifibrotic therapy disrupts stromal barriers and modulates the immune landscape in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79:372–386. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vennin C, et al. Reshaping the Tumor Stroma for Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:820–838. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.