Abstract

Slip-related falls can be induced by instability or limb collapse, but the key factors that determine these two fall causations remain unknown. The purpose of this study was to investigate the factors that contribute towards instability-induced and limb-collapse-induced slip-related falls by investigating 114 novel slip trials. The segment angles and moments of the recovery limb after slip-onset from pre-left-touchdown (pre-LTD) to post-left-touchdown (post-LTD) were calculated, and logistic regression was used to detect which variable contributed most to instability-induced and limb-collapse-induced falls. The results showed that recovery from instability was determined by the angle of the thigh at left-touchdown (LTD) (87.7%), while recovery from limb collapse was determined by the angle of the shank at post-LTD (90.4%). Correspondingly, instability-induced falls were successfully predicted (81.5%) based on the initial thigh angle at pre-LTD and the following peak thigh moment, while limb-collapse-induced falls were successfully predicted (85.5%) based on the initial shank angle at LTD and the following peak shank moment. According to our findings, taking a shorter recovery step and/or increasing the counterclockwise moment of the thigh after pre-LTD would help individuals resist instability-induced falls, while taking a larger recovery step and/or increasing the clockwise moment of the shank post-LTD would help resist limb-collapse-induced falls. The findings of this study are crucial for future clinical applications, because individually tailored reactive balance training could be provided to reduce vulnerability to specific types of falls and improve recovery rates post-slip exposure.

Keywords: recovery step, instability, limb collapse, segment moment, vulnerability

Introduction

Slip-related falls in older adults can lead to serious consequences including hip or arm fractures, traumatic head injuries, and even death.21, 29 Previous studies have identified instability and limb collapse to be two major causes of slip-related falls during walking.17, 36 The former is related to one’s stability control (in the horizontal plane), while the latter is related to one’s limb support against gravity (in the vertical plane). After experiencing a balance disturbance, individuals must maintain their center of mass (COM) state within their stability limits35 to keep their COM from falling towards the ground and prevent a fall. An effective compensatory (recovery) step taken in response to a perturbation can often be sufficient to combat both instability and limb collapse to arrest a fall, but if instability or limb collapse cannot be resisted after taking a recovery step, a fall becomes inevitable.31 Correspondingly, these falls can be divided into instability-induced falls (usually feet-forward falls when a person fails to recover from instability) and limb-collapse-induced falls (usually split falls when insufficient limb support is applied).37 Further, it was found that older adults were likely to repeatedly fall due to the same cause (instability or limb collapse) during their continuous exposure to a laboratory-induced slip, indicating that specific types of falls may be related to specific vulnerabilities. In order to overcome this specific vulnerability, it is important to understand the mechanisms of these falls by exploring how the unrecoverable instability or limb collapse was produced.

Based on the fall diagnostic approach developed in our previous study, the cause for each slip-related fall can be detected, and the type of fall (instability-induced fall or limb-collapse-induced) can be attributed to different reactive responses.31 Thus, the key factors that initiate these two types of falls should be differentiated. Many previous studies have investigated the roles of lower limb segments or joints in slip-related falls.25, 30, 34, 39 These previous studies found that a decrease in the foot and knee angles of the slipping limb before slip onset2 or a counterclockwise angular rotation (flexion, Fig. 1) of the shank of the slipping limb after slip onset could improve stability by reducing the velocity (slip intensity) of the base of support (BOS).3 However, no study has successfully decoupled the key factors for instability- and limb-collapse-induced falls, and the lower limb segments’ specific contributions to these two different causations of falls remain unknown. Moreover, these studies focused only on the slipping limb and not on the recovery limb.2, 3 In reality, recovery from a loss of balance following a slip relies heavily on an effective recovery step when grasping is not an option,23 and the recovery limb plays a key role in regaining stability in the post-slip phase.36 In addition to improving stability, recovery stepping can also enhance limb support by providing an additional supporting vertical force against gravity after touchdown of the recovery foot (LTD),31 and, therefore, it is important to examine the recovery limb’s role in avoiding a fall following a backward loss of balance.

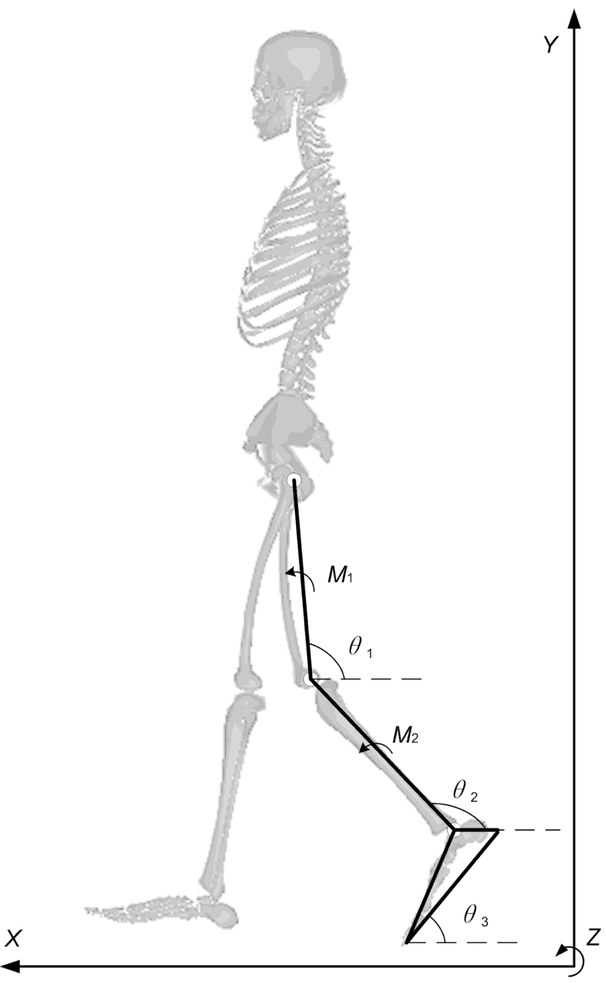

Figure 1.

Schematic of the 7-link, 9-degree-of-freedom, sagittal-plane model of the human body. θ1, θ2, and θ3 represent the angle of the thigh, shank, and foot, respectively. M1 and M2 represent the moment applied on the thigh and shank, respectively. The positive X-axis is in the direction of forward progression and the positive Y-axis is upward. Positive segment rotation is along the positive Z-axis (counterclockwise).

Studies have also previously analyzed the individual lower limb joint moments in the sagittal plane during a slip in gait.3, 39 They found that stability was related to knee flexor, hip extensor, and plantar flexor moments following slip onset in gait,39 while limb-collapse (resulting in a lack of recovery stepping during sit-to-stand) was attributed to insufficient knee extensor and hip extensor moments of the lower limbs following slip onset.27 However, it is important to note that restriction of analysis to any single joint may lead to an erroneous diagnosis34 as any other joint could compensate for the lack of support at a particular joint.33, 34 For example, the counterclockwise rotation (flexion) of the shank is controlled by both the knee flexor and plantar flexor moments.32 The counterclockwise rotation of the shank could, therefore, be achieved by increasing the knee flexor moment or the plantar flexor moment, and both possibilities could result in identical movements. Due to the compensating effect between joint moments, this paper analyzes the total moment applied on each of the three lower limb segments instead of focusing on the individual joint moments.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate both the kinematic and kinetic factors of the recovery limb and their role in determining falls induced by instability and/or limb collapse. We hypothesized that instability-induced falls and limb-collapse-induced falls could be predicted by specific segment angles of the recovery limb at specific instants (Hypothesis 1). As the angular rotation of each segment was controlled by the total moment applied on it, we further hypothesized that falls due to instability and falls due to limb collapse would be induced by an overall insufficient moment applied on a certain segment of the recovery limb (Hypothesis 2). In addition to the segment moment, the initial status of each segment could also affect its motion according to the inverse-dynamic model. Therefore, the impact of the specific combination of initial segment angle and the subsequent moment on fall risk was also investigated in this study.

Methods

Participants

114 community-dwelling older adults (≥ 65 years) from our database were included in this study (age: 72.5 ± 5.3 years; height: 163.9 ± 12.2 cm; mass: 76.0 ± 14.0 kg; female: 33). All participants were screened via clinical measures before their training session, and they were excluded if they had any neurological, musculoskeletal, cardiopulmonary, or any other systemic disorders. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board in the University of Illinois at Chicago (IRB#: 2000-0788), and all participants provided written informed consent. The research was carried out under the supervision of a NIH program officer, who ensured that the research was in compliance with all standards and policies, including any concerns related to the participants enrolled in the study. Among the participants, 80 fell after taking a single recovery step, including those who fell after an aborted step, while the other 34 successfully recovered by taking a single recovery step.

Experimental setup

The slip was induced by releasing a pair of side-by-side, low-friction, movable platforms embedded near the middle of a seven-meter walkway. The platforms were firmly locked during the first ten walking trials. During the slip trial, a computer-controlled triggering mechanism released the platform, allowing it to slide freely in the anterior-posterior (AP) direction for up to 90 cm once the subject’s right (slipping) foot landed on it.24 Participants were instructed to walk at their preferred speed and in their preferred manner, and they were told that a slip may or may not happen during any of the trials. All participants experienced at least two unannounced slips, in which they were not aware of where, when, and how the slip would occur, and the first slip trials were analyzed for this study.

During all trials, participants were equipped with a full-body safety harness which was connected by shock-absorbing ropes to a loadcell (Transcell Technology Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL). The loadcell was mounted on an overhead trolley on a track above the walkway. A fall was identified if the peak loadcell force measured during a slip exceeded 30% of the participant’s body weight.38 The harness allowed participants to walk freely while providing protection against the body coming into contact with the floor surface. Kinematics from a modified Helen Hayes full-body marker set (30 retro-reflective markers) were recorded by an eight-camera motion capture system (Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA). Kinematic data was sampled at 120 Hz and was synchronized with the force plate and loadcell data, which were collected at 600 Hz.

Fall diagnosis method

A fall diagnostic method was used based on the presence of unrecoverable instability and unrecoverable limb collapse.31 Stability was calculated as the shortest distance from the instantaneous COM state to the thresholds (limits) against backward balance loss. Outside the limits (< 0), recovery is theoretically impossible without re-establishing a new BOS. Limb support was computed based on the vertical ground reaction force and body weight [(GRF - BW) × BW−1]. Negative limb support (< 0) indicated an insufficient supporting force, leading to continuous vertical descent of the COM.

Unrecoverable instability was defined as a stability measure which remains continuously outside the limits of stability (< 0) and never returns to inside the stability limits (> 0) until an actual fall occurs. Similarly, unrecoverable limb collapse was defined as a continuous waning of limb support (< body weight) until the occurrence of a fall. The onset timings of unrecoverable instability, or unrecoverable limb collapse, if present, were detected and compared. The earliest recorded event was used to help identify whether the fall was induced by instability (Group 1) or limb collapse (Group 2), or else if the slip resulted in a recovery (Group R). All participants were divided into these three groups. By comparing Group F1 to Group R, we expected to explore the mechanism of segment movement which determined unrecoverable instability, and by comparing Group F2 to Group R, we expected to explore the mechanism of segment movement which determined unrecoverable limb collapse.

Outcome variables

The segment (thigh, shank, and foot) angles in the sagittal plane were defined as the angle between a segment and the horizontal plane (Fig. 1), and the joint moment was calculated using subject-specific musculoskeletal sagittal-plane models (7-link, 9-degree-of-freedom) in OpenSim version 3.36 with inverse-dynamics formulation (Fig. 1). The individual models were scaled according to each subject’s anthropometric measurements.10 The segment moment was a combination of adjacent joint moments. The moment applied on each segment was calculated using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Here, M1 and M2 represent the counterclockwise (Fig. 1) moment applied on the thigh and shank, respectively. The moment applied on the foot was the same as the ankle joint moment. A counterclockwise moment on the thigh could lead to hip extension, a counterclockwise moment on the shank could lead to knee flexion, and a counterclockwise moment on the foot could lead to plantar flexion.

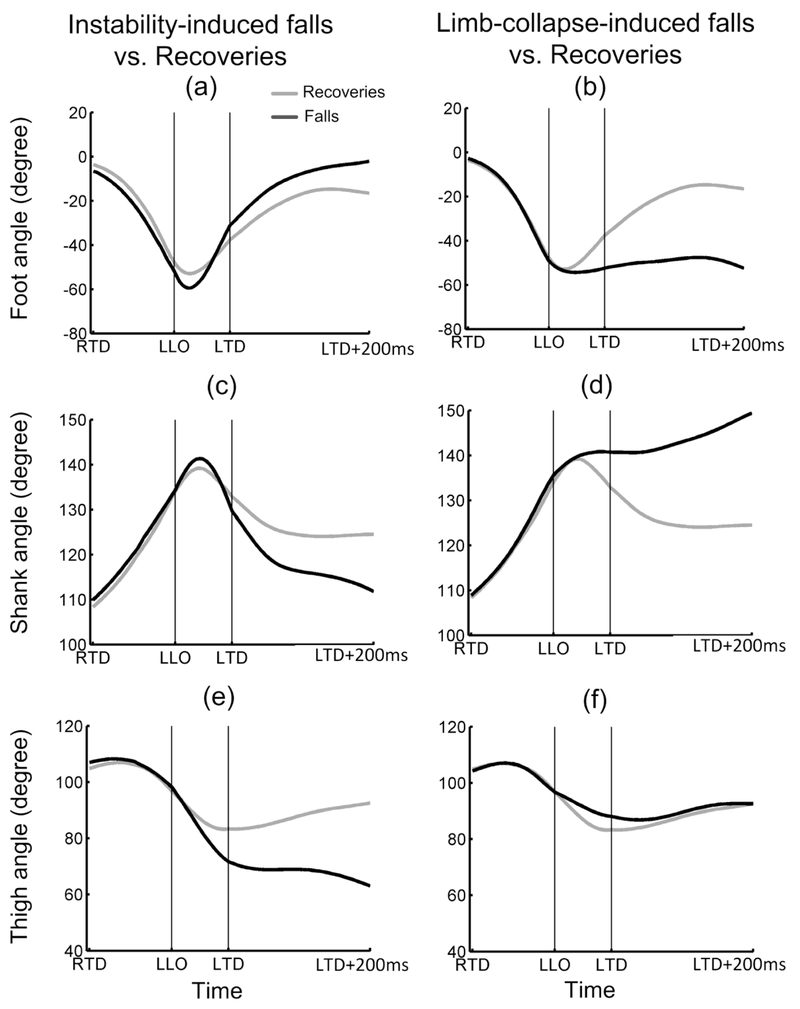

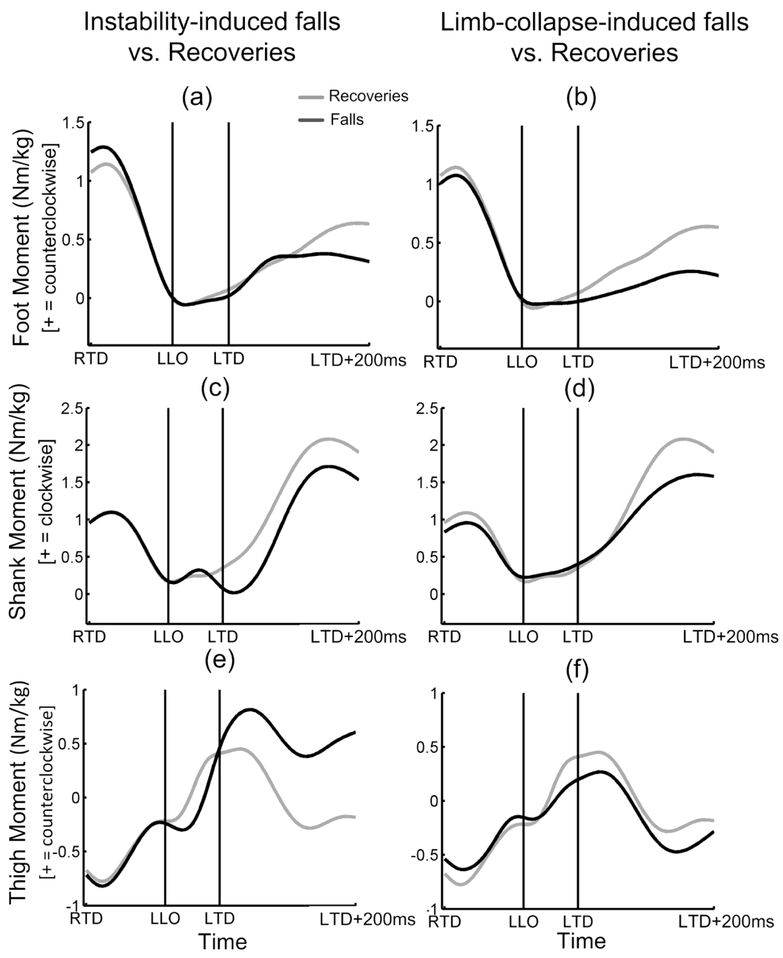

Our preliminary study (see Appendix) revealed that none of the segment angle curves of the recovery limb started deviating from each other between falls and recoveries before pre-left-touchdown (pre-LTD = LTD – 80ms) (Fig. 2), while all of the segment angle curves had already deviated from each other between falls and recoveries after post-left-touchdown (post-LTD = LTD + 110ms). The segment moment curves also showed similar tendencies (Fig. 3). Although the difference between falls and recoveries was even larger at LTD + 200ms compared to that at post-LTD (Fig. 2 and 3), this instant might be too late to adopt proper reactive action for fall prevention, as some participants had already fallen (harness fall-arrest) before 200ms after LTD.37 Hence, segment angle and moment from pre-LTD to post-LTD were analyzed in this study, and this duration could be divided into a swing phase (pre-LTD to LTD) and a stance phase (LTD to post-LTD).

Figure 2.

The curve of the average sagittal angle of the segment (thigh/shank) for falls (black curve) and recoveries (gray curve, N = 34). The average shank angle (a), thigh angle (c), and foot angle (e) were compared between Group F1 (instability-induced falls, N = 31) and Group R (recoveries), and the average shank angle (b), thigh angle (d), and foot angle (f) were compared between Group F2 (limb-collapse-induced falls, N = 49) and Group R.

Figure 3.

The curve of average moments applied on the segment (thigh/shank) in falls (black curve) and recoveries (gray curve, N = 34). The average moment on the shank (a), thigh (c), and foot (e) were compared between Group F1 (instability-induced falls, N = 31) and Group R (recoveries). The average moment on the shank (b), thigh (d), and foot (f) were compared between Group F2 (limb-collapse-induced falls, N = 49) and Group R.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA were performed to compare the group effects on age, body mass, and body height. χ2 test was used to examine the gender distribution among the three groups.

To identify the key kinematic determinant of falls from instability, univariate logistic regression was used to classify Group F1 and Group R with recovery segment (foot, shank, and thigh) angles (at pre-LTD, LTD, and post-LTD) as independent determinants. Similarly, in order to identify the key determinant of falls from limb collapse, Group F2 and Group R were distinguished using the same logistic regression with each segment angle as the predictor.

To identify the key kinetic determinant, the peak segment moments in the swing phase and in the stance phase, related to the key segment angle acquired from the above analysis, were each inputted into a univariate logistic regression model for fall prediction. As segment angle was not only affected by the moment applied on the corresponding segment, but also affected by its initial states (i.e. segment angle), multivariate logistic regression was also used to derive the linear model to predict the outcome (fall or recovery) with the peak moment and initial angle of the corresponding segment as independent variables.

Segment moment is a combination of two adjacent (distal and proximal) joint moments. Therefore, to test which joint moment contributed more to fall prediction, multivariate logistic regression was also conducted with initial segment angle and corresponding joint moments as the predictor. For this analysis, the same instant at which the corresponding segment moment reached its peak was chosen for both adjacent joint moments. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). For all analyses, p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Among the 80 falls, 31 falls (Group F1) were induced by unrecoverable instability, while the other 49 falls (Group F2) were induced by unrecoverable limb collapse. Although the 34 non-fallers (Group R) did all experience both instability and limb collapse, they were able to successfully recover their stability and limb support by taking a single recovery step. One-way ANOVA showed a group effect on body weight, and the gender distribution among these groups was different.

Out of all the segment angles of the recovery limb, thigh angle at LTD was highly correlated with instability-induced falls (p < 0.001, Table 2). This segment angle distinguished Group F1 (instability-induced falls) from Group R (recoveries) with an accuracy of 87.7% at LTD, which was 18.5% greater than the accuracy at pre-LTD using the same variable. Although the thigh angle at post-LTD provided a higher accuracy compared to at LTD, the increment of accuracy from LTD to post-LTD was only 4.6%. In contrast, limb-collapse-induced falls were found to be highly correlated with shank angle at post-LTD, distinguishing Group F2 (limb-collapse-induced falls) from Group R (recovery) with an accuracy of 90.4% (p < 0.001, Table 2), which was 20.5% higher than for LTD.

Table 2.

Comparison of the prediction accuracy of fall incidences based on segment angles at the investigated events (Pre-LTD, LTD, and Post-LTD) for Group F1 (31 instability-induced falls), Group F2 (49 limb-collapse-induced falls), and Group R (34 recoveries). A logistic regression model was used to calculate the prediction accuracy for each variable. For Group F1&R, whether or not instability would result in a fall was predicted, and for Group F2&R, whether or not limb collapse would result in a fall was predicted. Here * indicates p < 0.05 for the model coefficient.

| Variable | Event | F1&R | F2&R |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foot angle | Pre-LTD | 52.3% | 59.0% |

| LTD | 61.5% | 73.5%* | |

| Post-LTD | 63.1%* | 80.7%* | |

| Shank anglea | Pre-LTD | 52.3% | 59.0% |

| LTD | 61.5% | 69.9%* | |

| Post-LTD | 66.2%* | 90.4%* | |

| Thigh anglea | Pre-LTD | 69.2%* | 63.8%* |

| LTD | 87.7%* | 56.6% | |

| Post-LTD | 92.3%* | 59.0% |

the shank angle and thigh angle of the left limb at LTD have a positive relationship (correlation coefficient = 0.66, p<0.001).

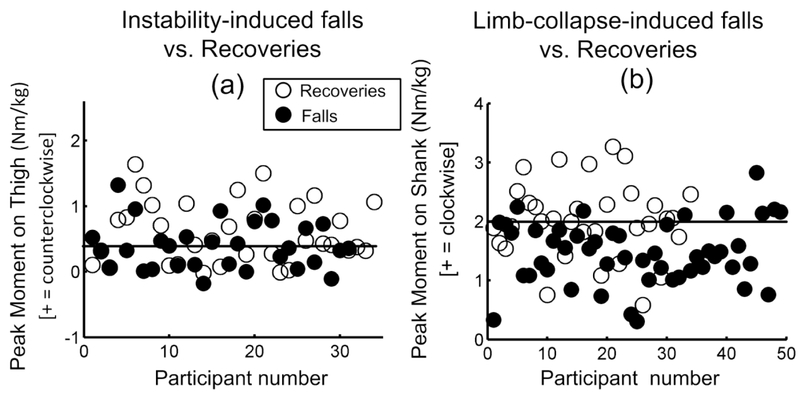

Although Group F1 and Group R could be classified with an accuracy of about 90% based on thigh angle at LTD, the corresponding peak thigh moment (from pre-LTD to LTD) could only categorize the slip outcomes with an accuracy of 58.5% (p = 0.067, Fig. 4a). Additionally, the peak shank moment (from LTD to post-LTD) could only categorize Group F2 and Group R with 68.7% accuracy (p = 0.003, Fig. 4b), which was much lower than the prediction accuracy (90.4%) using the corresponding shank angle at post-LTD.

Figure 4.

The distribution of the peak segment moments for the different groups. The filled circle indicates falls and the hollow circle indicates recoveries. (a) The distribution of the peak moment on the thigh from pre-LTD to LTD was compared between Group F1 (instability-induced falls, N = 31) and Group R (recoveries, N = 34). (b) The distribution of the peak moment on the shank from pre-LTD to LTD was compared between Group F2 (limb-collapse-induced falls, N = 49) and Group R. The bold horizontal line indicates the threshold value of the segment moment for categorizing recoveries and falls.

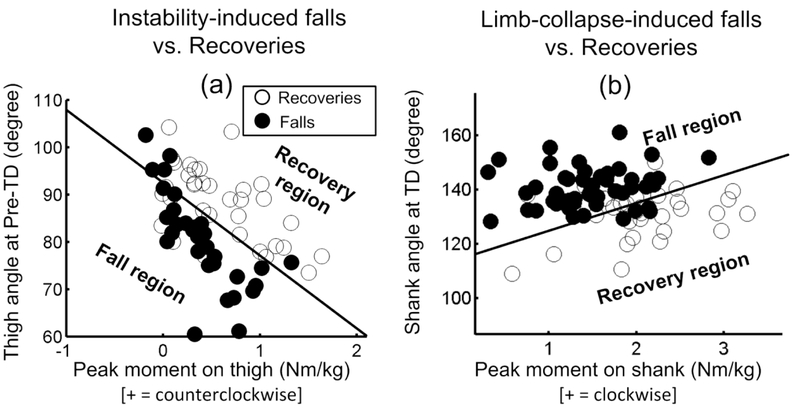

After taking into account the initial thigh angle (at pre-LTD) along with the subsequent peak thigh moment from pre-LTD to LTD, instability-induced falls could be predicted with an accuracy of 81.5% (p < 0.001 for both, Fig. 5a). Similarly, limb-collapse-induced falls could be predicted by shank angle at LTD and peak shank moment (LTD to post-LTD) with an accuracy of 85.5% (p < 0.001 for both, Fig. 5b). However, limb-collapse-induced falls could not be predicted based on thigh moment and thigh angle, and instability-induced falls could not be predicted based on shank moment and shank angle (p > 0.05 for both).

Figure 5.

The fall prediction model based on the segment peak moments and the initial segment angles. (a) The distribution of the thigh angle and the moment on the thigh were compared between Group F1 (instability-induced falls, N = 31) and Group R (recoveries, N = 34). (b) The distribution of the shank angle and the moment were compared between Group F2 (limb-collapse-induced falls, N = 49) and Group R. The straight line was calculated based on the logistic regression results, this line divided the 2D space into a recovery region and a fall region.

Using initial thigh angle (at pre-LTD) and its adjacent peak joint moments (hip and knee), Group F1 and Group R could be categorized with an accuracy of 80.0% (Table 3). Of these two joint moment predictors, the knee extensor moment (B = 6.06, p < 0.001) contributed slightly more to preventing unrecoverable instability than the hip extensor moment based on the beta value (B = 4.76, p < 0.001). Similarly, Group F2 and Group R could be categorized with an accuracy of 86.7% using initial shank angle (at LTD) and its adjacent peak joint moments (ankle and knee), with the ankle extensor moment (B = 3.31, p = 0.001) contributing slightly more to preventing unrecoverable limb collapse than the knee extensor moment (B = 1.56, p = 0.029).

Table 3.

The instability prediction and limb collapse prediction based on joint moments using multivariate logistic regression. For Group F1 (31 instability-induced falls) and Group R (34 recoveries), whether instability would result in a fall was predicted, while for Group F2 (49 limb-collapse-induced falls) and Group R, whether limb collapse would induce a fall was predicted. Here B value denotes beta coefficients.

| Model | Predictors | B value | P value | Total accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instability prediction | Thigh angle | 0.24 | <0.001 | |

| Knee joint moment | 6.06 | <0.001 | 80.0% | |

| hip joint moment | 4.79 | <0.001 | ||

| Limb collapse prediciton | Shank angle | −0.19 | <0.001 | |

| Ankle joint moment | 3.31 | 0.001 | 86.7% | |

| Knee joint moment | 1.56 | 0.029 |

Discussion

This study found that falls due to different causes were determined by different segments within different temporal domains (Table 2). The angle of the left (recovery) thigh at LTD determined whether or not an instability-induced fall would occur, while the angle of the left shank at post-LTD determined whether or not a limb-collapse-induced fall would occur (Hypothesis 1). However, although the thigh angle at LTD was affected by the thigh moment from pre-LTD to LTD, this peak thigh moment could not predict instability-induced falls. Additionally, the peak moment of the shank during the stance phase could only predict limb-collapse-induced falls with a much lower accuracy of 68.7%, and these findings were, therefore, inconsistent with our second hypothesis.

Following an unexpected, large-magnitude novel slip, a person usually experiences both backward instability and vertical limb collapse. By making use of effective recovery strategies, individuals can re-establish and regain their stability, as well as enhance their limb support, and this is important in order to avoid a fall from unrecoverable instability, limb collapse, or both.31 Instability-induced falls were differentiated from recoveries based on the left thigh angle (87.7% accuracy at LTD), and limb-collapse-induced falls were distinguished from recoveries based on the left shank angle (90.4% accuracy at post-LTD) (Table 2). Hence, we can conclude that control of the recovery thigh determines whether or not stability can be regained, while control of the recovery shank determines whether or not limb collapse could be resisted. Those results highlight the contribution of the recovery limb for preventing slip-related falls.

Interestingly, we also found that stability and limb support were restored the most during different phases of the gait cycle. Whether or not instability could be resisted was mainly determined during the swing phase (before LTD), while whether or not limb collapse could be resisted was mainly determined during the stance phase (after LTD). In order to regain stability, the most effective method proposed previously was to maintain one’s COM within their BOS,2 which could be achieved either by enlarging the BOS or by shifting the COM forwards. Taking a recovery step could rebuild the BOS, hence improving stability. However, if the angular rotation of the recovery limb thigh was too large during the swing phase, then the COM would still be posterior to the boundary of the enlarged BOS after recovery stepping. Moreover, as the propulsive force applied on the COM is proportional to the difference between the COM and the center of pressure (COP, located within the BOS),18 such recovery stepping would lower this propulsive force, hence worsening stability. These factors may explain why instability-induced falls were greatly affected in the swing phase. In contrast, the stance phase was most important for preventing limb-collapse-induced falls, as a sufficient supporting force was required to reverse the vertical descent of the COM. Therefore, the stance phase contributes more for enhancing limb support, as the recovery limb can only provide an extra supporting force following its touchdown.

Although slip outcomes were able to be determined by the angle of a specific segment with about 90% accuracy, the corresponding peak moments showed a much lower (<70%) predictive capacity (Fig. 4). This lower predictive capacity is because slip outcomes are also affected by other factors, such as the initial segment angle, which is important because an improper initial segment angle would require a larger moment to reach a target value. Specifically, initial shank angle at LTD determined the moment arm for the body weight vector, according to inverse-dynamics formulation, thus a larger shank-ground angle would increase the moment arm for the body weight vector which would increase hip dropping velocity and ultimately increase the risk of a limb-collapse-induced falls. Therefore, a smaller (more vertical) initial angle and a larger clockwise moment on the shank after LTD were required in order to avoid unrecoverable limb collapse (Fig. 5). Similarly, to maintain the COM inside the BOS and avoid unrecoverable instability, a larger (less vertical) initial thigh angle and a sufficient counterclockwise moment on the thigh were required. A sufficient moment was determined by the boundary categorizing recoveries from falls, which was calculated using logistic regression. Based on the results of logistic regression, a 2D space was built which indicates the segment status during recovery stepping (the two axes represent segment moment and segment angle, respectively). This space was divided into a recovery region and a fall region by this boundary (Fig. 5), and individuals whose segment statuses were located in the recovery region would have a great likelihood to recover, while those in the fall region would be likely to fall. The increment of segment moment could increase individuals’ chance of being located in the recovery region. Therefore, any moment that could make segment status be located inside the recovery region would be considered a sufficient moment.

As discussed above, an insufficient segment moment could increase the likelihood of a fall. Consistently, it was proposed that increasing muscle weakness (especially lower extremity weakness) with aging is one of the risk factors for falls in older adults,7, 19 and muscle strength training was found to be effective for fall prevention in older adults.12, 14, 16 However, the extent to which specific muscular strength could contribute to fall prevention is unclear. Our results indicated that the clockwise moment of the shank, which is the sum of the planter flexor moment and the knee extensor moment, was related to limb-collapse-induced falls, while the counterclockwise moment of the thigh, which is the sum of the knee extensor moment and the hip extensor moment, was related to instability-induced falls. The planter flexor moment contributed more than the knee extensor moment to the total shank moment, while the knee extensor moment contributed slightly more than the hip extensor moment to the total thigh moment. Consistently, it has been suggested that the recovery limb should extend the knee joint as quickly as possible for fall prevention.13 As older adults tend to fall due to the same cause (i.e., instability or limb-collapse),31 leg-extension exercises and whole body vibration training,5, 28 which could increase knee extensor strength, may be helpful for individuals who tend to fall due to instability, while plantar flexion exercises and resistance training, 9, 26 which could increase planter flexor strength, may be helpful for individuals who tend to fall due to limb collapse.

In addition to changing the control of segment moment, the adjustment of the recovery limb landing posture could also decrease fall incidences. A thigh angle which is sufficient to resist instability should be greater than 90° at pre-LTD (Fig. 5a), and a shank angle which is sufficient to resist limb collapse should be less than 120° at LTD (Fig. 5b). In this case, a larger segment moment (counterclockwise thigh moment for instability and clockwise shank moment for limb collapse) would not be required to prevent a fall, as a small segment moment (~0 Nm) could make the segment status (point in Fig. 5) be located in the recovery region, hence lowering the likelihood of a fall. This was consistent with previous findings that a decrease in the distance between the COP and the COM would reduce the magnitude of muscular strength required to prevent a fall.11 However, the left shank angle and the left thigh angle were positively correlated (r = 0.46, p < 0.001, Table 2), which means the increment of the thigh angle would be accompanied by the increment of the shank angle, and vice versa.

Taking into consideration both muscular strength and posture of the recovery limb, we can state that individuals with sufficient limb support but poor stability might benefit from taking a shorter recovery step (larger thigh and shank angles), while individuals with a stable COM state but inefficient limb support might benefit from taking a larger recovery step (smaller thigh and shank angles). The optimal step length might be determined by stability and limb support prior to recovery foot touchdown. Although few studies investigated whether the recovery foot landing location was adjustable, it was proposed that the energy level of the recovery leg, which could accelerate the leg segments through the pre-swing phase, was related to the recovery step length.20 Moreover, recovery step length is often scaled to the overall gait step length and gait speed.8 Hence, it was possible the recovery step length could be adjustable via specific gait-related training, however this possibility warrants further examination.

There are many other factors associated with a recovery response. As shown in Table 1, both gender and body weight were significantly different among the three slip outcome groups. The difference in gender distribution might be attributed to the gender difference in lower extremity muscle strength. Males had significantly larger quadriceps and hamstring isokinetic peak torque than females,15 hence they could produce larger knee extensor moments and consequently lower their risk of falls. The limb-collapse-induced fallers had a larger body weight compared to the other two groups. It is reasonable to postulate that the greater body weight led to a rapid deterioration of stability and limb support, which forced individuals to have a very quick landing (shorter step). Additionally, gait speed might also be another factor related to this quick landing. Due to the aforementioned relationship between recovery step length and gait speed, those likely to have limb-collapse-induced falls might also have a slower gait speed during their daily living. Besides the segment analyzed in this study, trunk segment was also associated with fall risk,4 and including this segment might further improve the predictive capacity of our fall prediction model, however a future study will work on determining this.

Table 1.

The demographics with means ± SD for each group. R denotes recoveries, F1 denotes instability-induced falls, and F2 denotes limb-collapse-induced falls.

| Slip Outcomes |

p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (N = 34) | F1 (N = 31) | F2 (N = 49) | ||

| Age (year) | 72.6 ± 6.6 | 71.8 ± 3.4 | 72.8 ± 5.5 | 0.39 |

| Gender (% male) | 41 | 29 | 15 | <0.001 |

| Body mass (kg) | 75.4 ± 12.1 | 69.3 ± 12.3 | 81.3 ± 14.0 | <0.001 |

| Body height (cm) | 164 ± 19 | 165 ± 8 | 163 ± 6 | 0.80 |

The results of this study must be considered in light of its lack of inclusion of a specific type of instability-induced fall. This study did not include falls induced by medio-lateral (ML) instability, as a previous study found that only 8.2% of instability-induced falls were attributed to unrecoverable instability in the ML direction.31 Therefore, for simplification, the variables in the ML direction were not taken into consideration. This might limit the translation of these findings to daily life falls, especially falls in the ML direction. A future study will focus on the key determinates affecting this type of fall. Although the conclusions of this study were based on a moveable-platform-induced laboratory slip, previous studies showed locomotor-balance skills acquired from training with moveable platforms can be successfully transferred to oil-lubricated surfaces,1 as well as in daily living.22 Those studies indicated that the balance skills to resist slip-induced falls can be used in different environmental contexts, hence the fall prevention strategies proposed in this study should also be suitable for individuals at risk of slip-induced falls in their daily lives.

In conclusion, this study investigated the role of lower limb segments in instability-induced and limb-collapse-induced falls following a novel slip. The study found that whether or not stability could be regained after LTD was mainly determined by the thigh angle at LTD, while the post-LTD shank angle was the main determinant for whether or not one could recover from limb collapse. Limb-collapse-induced and instability-induced falls could be predicted based on the peak moment on the fall type’s corresponding segment along with the initial segment angle. We previously showed that the causative factors for slip-induced falls in older adults for the same type of perturbation encountered remained the same from the first to second slip encounter (i.e. either an instability-induced fall or a limb-collapse-induced fall).31 The findings of this study suggest that older adults predisposed to instability-induced falls could recover by taking a shorter recovery step and/or increasing the counterclockwise moment on the thigh of the recovery leg during the swing phase. Conversely, older adults predisposed to limb-collapse-induced falls could recover by taking a larger recovery step and/or increasing the clockwise moment on the shank of the recovery leg during the stance phase. The findings of this study are crucial for future clinical applications, because individually tailored reactive balance training could be provided to people with vulnerability to specific types of falls, which could ultimately reduce the overall likelihood of falls among community-dwelling older adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R01-AG029616 and NIH R01-AG044364. We thank Ms. Alison Schenone for helpful edits.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Bhatt T and Pai YC. Generalization of Gait Adaptation for Fall Prevention: From Moveable Platform to Slippery Floor. Journal of Neurophysiology 101: 948–957, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatt T, Wening JD and Pai YC. Adaptive control of gait stability in reducing slip-related backward loss of balance. Experimental Brain Research 170: 61–73, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cham R and Redfern MS. Lower extremity corrective reactions to slip events. Journal of Biomechanics 34: 1439–1445, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crenshaw JR, Rosenblatt NJ, Hurt CP and Grabiner MD. The discriminant capabilities of stability measures, trunk kinematics, and step kinematics in classifying successful and failed compensatory stepping responses by young adults. Journal of Biomechanics 45: 129–133, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delecluse C, Roelants M and Verschueren S. Strength increase after whole-body vibration compared with resistance training. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 35: 1033–1041, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delp SL, Anderson FC, Arnold AS, Loan P, Habib A, John CT, Guendelman E and Thelen DG. OpenSim: open-source software to create and analyze dynamic Simulations of movement. Ieee Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 54: 1940–1950, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding L and Yang F. Muscle weakness is related to slip-initiated falls among community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Biomechanics 49: 238–243, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espy DD, Yang F, Bhatt T and Pai YC. Independent influence of gait speed and step length on stability and fall risk. Gait Posture 32: 378–382, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferri A, Scaglioni G, Pousson M, Capodaglio P, Van Hoecke J and Narici MV. Strength and power changes of the human plantar flexors and knee extensors in response to resistance training in old age. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 177: 69–78, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaffney BM, Harris MD, Davidson BS, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Christiansen CL and Shelburne KB. Multi-Joint Compensatory Effects of Unilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty During High-Demand Tasks. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 44: 2529–2541, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn ME and Chou LS. Age-related reduction in sagittal plane center of mass motion during obstacle crossing. Journal of Biomechanics 37: 837–844, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karinkanta S, Piirtola M, Sievanen H, Uusi-Rasi K and Kannus P. Physical therapy approaches to reduce fall and fracture risk among older adults. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 6: 396–407, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kojima S, Nakajima Y and Takada J. Kinematics of the compensatory step by the trailing leg following an unexpected forward slip while walking. J Physiol Anthropol 27: 309–315, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaStayo PC, Ewy GA, Pierotti DD, Johns RK and Lindstedt S. The positive effects of negative work: Increased muscle strength and decreased fall risk in a frail elderly population. Journals of Gerontology Series a-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 58: 419–424, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lephart SM, Ferris CM, Riemann BL, Myers JB and Fu FH. Gender differences in strength and lower extremity kinematics during landing. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 162–169, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, Eng JJ, Janssen PA, Lord SR and Mckay HA. Resistance and agility training reduce fall risk in women aged 75 to 85 with low bone mass: A 6-month randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52: 657–665, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mak MKY, Yang F and Pai YC. Limb Collapse, Rather Than Instability, Causes Failure in Sit-to-Stand Performance Among Patients With Parkinson Disease. Physical Therapy 91: 381–391, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morasso PG, Spada G and Capra R. Computing the COM from the COP in postural sway movements. Human Movement Science 18: 759–767, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreland JD, Richardson JA, Goldsmith CH and Clase CM. Muscle weakness and falls in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52: 1121–1129, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neptune RR, Kautz SA and Zajac FE. Contributions of the individual ankle plantar flexors to support, forward progression and swing initiation during walking. Journal of Biomechanics 34: 1387–1398, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norton R, Campbell AJ, LeeJoe T, Robinson E and Butler M. Circumstances of falls resulting in hip fractures among older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45: 1108–1112, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pai YC, Bhatt T, Yang F and Wang E. Perturbation Training Can Reduce Community-Dwelling Older Adults’ Annual Fall Risk: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journals of Gerontology Series a-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 69: 1586–1594, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pai YC, Wening JD, Runtz EF, Iqbal K and Pavol MJ. Role of feedforward control of movement stability in reducing slip-related balance loss and falls among older adults. Journal of Neurophysiology 90: 755–762, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pai YC, Yang F, Bhatt T and Wang E. Learning from laboratory-induced falling: long-term motor retention among older adults. Age 36: 1367–1376, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pavol MJ and Pai YC. Deficient limb support is a major contributor to age differences in falling. Journal of Biomechanics 40: 1318–1325, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Persch LN, Ugrinowitsch C, Pereira G and Rodacki ALF. Strength training improves fall-related gait kinematics in the elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Biomechanics 24: 819–825, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinovitch SN, Chiu J, Sandler R and Liu Q. Impact severity in self-initiated sits and falls associates with center-of-gravity excursion during descent. Journal of Biomechanics 33: 863–870, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roelants M, Delecluse C and Verschueren SM. Whole-body-vibration training increases knee-extension strength and speed of movement in older women. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52: 901–908, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevens JA and Sogolow ED. Gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall related injuries among older adults. Injury Prevention 11: 115–119, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang PF, Woollacott MH and Chong RKY. Control of reactive balance adjustments in perturbed human walking: roles of proximal and distal postural muscle activity. Experimental Brain Research 119: 141–152, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang SJ, Liu X and Pai YC. Limb Collapse or Instability? Assessment on Cause of Falls. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 47: 767–777, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winter DA Biomechanics and motor control of human movement. John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winter DA Kinematic and Kinetic Patterns in Human Gait - Variability and Compensating Effects. Human Movement Science 3: 51–76, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winter DA Overall Principle of Lower-Limb Support during Stance Phase of Gait. Journal of Biomechanics 13: 923–927, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang F, Anderson FC and Pai YC. Predicted threshold against backward balance loss following a slip in gait. Journal of Biomechanics 41: 1823–1831, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang F, Bhatt T and Pai YC. Role of stability and limb support in recovery against a fall following a novel slip induced in different daily activities. Journal of Biomechanics 42: 1903–1908, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang F, Espy D, Bhatt T and Pai YC. Two types of slip-induced falls among community dwelling older adults. Journal of Biomechanics 45: 1259–1264, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang F and Pai YC. Automatic recognition of falls in gait-slip training: Harness load cell based criteria. Journal of Biomechanics 44: 2243–2249, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang F and Pai YC. Role of individual lower limb joints in reactive stability control following a novel slip in gait. Journal of Biomechanics 43: 397–404, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.