Abstract

Background:

Studies on the association between folate/folic acid exposure and the development of allergic disease have yielded inconsistent results, which may be due, in part, to lack of data distinguishing folate from folic acid exposure.

Objective:

To examine the association between total folate, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF), and unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA) concentrations at birth and in early childhood and the development of food sensitization (FS) and food allergy (FA).

Methods:

A nested case control study was performed in the Boston Birth Cohort (BBC). Total folate, 5-MTHF, and UMFA were measured at birth and in early childhood. Based on food-specific IgE (sIgE) levels, diet, and clinical history, children were classified as FS (sIgE ≥0.35 kU/L), FA, or non-FS/FA (controls). Folate concentrations were divided into quartiles, and multiple logistic regression was used to estimate ORs and 95%CIs.

Results:

Of a total of 1,394 children, 507 FS and 78 FA children were identified. While mean total folate concentrations at birth were lower among those who developed FA (30.2 vs. 35.3 nmol/L; p=0.02), mean concentrations of the synthetic folic acid derivative, UMFA, were higher (1.7 vs. 1.3 nmol/L, p=0.001). Higher quartiles of UMFA at birth were associated more strongly with FA (OR 8.50; 95%CI 1.7–42.8; test for trend p=0.001). Neither early childhood concentrations of 5-MTHF nor UMFA were associated with the development of FS or FA.

Conclusion:

Among children in the BBC, higher concentrations of UMFA at birth were associated with the development of FA, which may be due to increased exposure to synthetic folic acid in utero or underlying genetic differences in synthetic folic acid metabolism.

Keywords: Food allergy, Folate, Folic acid, Unmetabolized folic acid, 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate

Introduction

Food allergy (FA) is a common childhood condition that is associated with a significant impairment in quality of life.(1) The prevalence of food allergy has rapidly increased over the past few decades,(2, 3) and understanding the etiology of this “food allergy epidemic” will likely shed light on modifiable risk factors that may be addressed to prevent the development of this condition. Among the many hypotheses for this recent increase in food allergy prevalence, those involving changes in our diet and nutrition are of particular interest.

One potential nutritional risk factor for the development of food allergy is folic acid exposure. Folate is a water-soluble B vitamin involved in homocysteine regulation, DNA synthesis, and DNA methylation (DNAm). DNAm is of particular interest, as it leads to heritable changes in gene expression and may be involved in the development of allergic disease.(4, 5) In 1991, folate supplementation in early pregnancy was shown to prevent the development of neural tube defects in newborns.(6, 7) This, along with subsequent evidence, prompted the United States and other industrialized countries to mandate fortification of cereals and grains with folic acid in 1998, leading to population-wide increases in folate concentrations,(8, 9) and temporally coinciding with the recent rise in food allergy prevalence.(2, 3)

Given the biologic plausibility that folate exposure may be a risk factor for the development of allergic disease, and the temporal association described above, many studies in recent years have examined the association between folate exposure and allergic outcomes, with conflicting results. These studies, however, vary widely in terms of the timing of exposure, study design, and folate exposure classification.(10) Furthermore, previous studies have only examined total folate and did not differentiate between specific forms of folate. Interestingly, when examining synthetic folic acid exposure, the majority of studies report that supplemental folic acid use during pregnancy is a risk factor for the subsequent development of childhood allergic disease,(11–18) but to date, the underlying mechanism for this association remains unclear.

Folic acid is the stable, synthetic form of naturally occurring folate, and in addition to fortified grains, it is added to infant formula, supplements, and vitamins. Folic acid, unlike folate, requires reduction to tetrahydrofolate by the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) in order to be further metabolized to 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF), the folate form involved in DNA methylation. This reduction step has limited capacity in humans and is overwhelmed when folic acid consumption exceeds approximately 250 mcg/day,(19) resulting in circulating unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA). UMFA, which was only observed in 55% of non-supplement users prior to folic acid fortification in 1998,(20) is now seen in >95% of Americans regardless of folic acid supplementation history.(21)

To date, no studies have examined the association between the forms of folate (metabolites 5-MTHF and UMFA) and allergic disease. The objective of this study was thus to use clinical and plasma specific IgE data from children enrolled in a longitudinal birth cohort, the Boston Birth Cohort, to examine the association between plasma total folate (which includes UMFA, 5-MTHF, and other folate metabolites), UMFA, and 5-MTHF and the development of food sensitization (FS) and food allergy (FA). As it is currently unknown whether the risk of developing FS and FA is determined in utero or in early life, we measured these concentrations at the time of birth and in early childhood. Given the previous literature suggesting that synthetic folic acid exposure during pregnancy is a risk factor for the development of allergic disease, we hypothesized that higher UMFA concentrations at birth would be associated with the development of FS and FA.

Methods

Study Design

The Boston Birth Cohort (BBC) is a prospective, observational, predominantly urban minority birth cohort designed to study pregnancy and child health outcomes. Details regarding the design, methods, and study population have been previously described elsewhere(22, 23) and are summarized in the Online Supplement. Starting in 2004, infants who enrolled at birth and continued to receive primary care at BMC were invited to participate in a follow-up study, the Children’s Health Study (CHS, n=3,163 as of July 2018). At follow-up visits in alignment with pediatric primary care visits, information on demographics, medical history, symptoms of food allergy, dietary intake, and lifestyle were collected through standardized questionnaires. Relevant health information, laboratory results, medications, and ICD-9/ICD-10 codes were extracted from the medical record, and blood samples were collected.

Our study included mother-infant pairs who were enrolled in the CHS who met the following criteria: 1) had available maternal plasma or cord blood samples at the time of delivery for folate measurement; 2) had available postnatal food-specific IgE measurements; and 3) completed the follow-up questionnaire assessing the child’s clinical symptoms when exposed to each of the 8 most common food allergens (cow’s milk, egg white, peanut, soy, shrimp, walnut, wheat, and cod) at one of the follow-up visits. Early childhood measurements were only included in these analyses if folate measurements were made prior to sIgE measurements and FA assessments. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of Boston University Medical Center, the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago (formerly Children’s Memorial Hospital), The University of Virginia, and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Folate Measurements

Total folate was measured in stored maternal plasma collected at enrollment (n=1,384) and in stored offspring plasma collected between 1 and 9 years of age (n=863) via a chemiluminescent immunoassay using a MAGLUMI 2000 Analyzer (Snibe Co LTD), as previously described.(24) Unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA) and 5-MTHF were measured in cord blood plasma from a subset of children (n=502) using isotope-dilution high performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), as previously described.(25) The same methodology was used to measure UMFA and 5-MTHF in stored offspring plasma collected between 6 months and 3 years of age (n=181). This method is highly correlated with total plasma folate measures from the more frequently used microbial assay (r2 = 0.97),(26) and total folate measurements have been shown to be stable to repeated freeze/thaw cycles.(27)

Food-Specific IgE Measurements

Food-specific IgE (sIgE) was measured for the 8 most common food allergens (egg white, cow’s milk, peanut, soy, shrimp, walnut, wheat and cod) in early childhood (n=1,390; mean age: 2.35±2.22 years; range 0–12 years) using ImmunoCAP® (Thermo-Fisher/Phadia, Kalamazoo, Michigan) at Quest Diagnostics. These assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s prescribed protocol,(28) and the detection limit was 0.35–100 kUA/L, which was the lower sIgE cut-off at the time the assays were run.

Food Sensitization and Food Allergy Definitions

Food sensitization (FS) was defined as food-specific IgE ≥ 0.35 kU/L to any of the food allergens tested. As oral food challenges were only performed as clinically indicated outside of this study, children were divided into five food allergy groups at each time point based on their food-specific IgE levels, clinical histories, medical records, and dietary intake, as previously described.(29) Further information is included in the Online Supplement and defined in Table E1. For the purpose of analyses, each child was placed in the highest food allergy category he/she attained over the period of postnatal follow-up. Food Allergy (FA) was defined as those who were in the highest category (“Confirmed/Convincing Food Allergy”), and they were compared to the combination of those who were either “Sensitized but Tolerant” or “Not Sensitized and Not Allergic.”

Covariates

Information on demographics, in utero, and post-natal exposures, such as race/ethnicity, infant feeding, maternal smoking, pre-natal folic acid intake, and maternal history of atopy were collected from the mothers via questionnaire and are further defined in the Online Supplement. Information was further collected from the medical record regarding mode of delivery, gestational age, maternal education, pre-pregnancy maternal BMI, and maternal age at delivery.

Statistical Analysis

The distributions of maternal, cord blood, and post-natal folate were examined by food sensitization (FS) and food allergy (FA) outcomes, and as folate concentrations were found to be non-normally distributed, they were divided into quartiles. Maternal and early-life characteristics were compared among those with and without FS or FA using chi-squared, student’s t-tests, and Mann-Whitney U tests, as appropriate. Pearson’s correlations were performed on log-transformed total folate, UMFA, and 5-MTHF values. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to investigate the associations of folate forms (total folate, UMFA, and 5-MTHF) with either FS or FA, adjusting for maternal age, maternal race, maternal education, maternal history of atopy, smoking, child’s gender, mode of delivery, breastfeeding history, child’s age when specific food IgE was measured, and child’s age when clinical symptoms on food ingestion was assessed (for FA). Multivariable logistic regression models were similarly used to examine the associations between pre-natal folic acid intake at each trimester and FS and FA outcomes, adjusting for the confounders mentioned above. In order to examine the independent effect of UMFA and 5-MTHF on allergic outcomes, cord blood UMFA models were additionally adjusted for 5-MTHF. Finally, sensitivity analyses for UMFA were performed in which a) children categorized as “Probable” and “Possible” food allergic were included as food allergic; b) FS was assessed using thresholds of 0.7 and 3.5 kU/L, and c) the population was limited to children who had sIgE levels and clinical symptoms of FA assessed at or prior to age 5. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, except for analyses comparing quartiles, in which a Bonferroni-corrected p value <0.017 was considered significant. As longitudinal data was not included in the same model, adjustments were not made for correlations among repeated measurements. All analyses were performed in Stata SE 14.1 (College Station, TX).

Results

Study Population

A total of 1,394 children were included in this study, of whom 1,384 (99%) had total folate measured in maternal plasma (Figure E1). Compared to the entire CHS population, the subcohort had a lower proportion of preterm children (24.1% v 28.1%, p=0.007), but otherwise had similar demographic characteristics (Table E2). After birth, children underwent an average of 2.99 follow-up visits (range 1–11). The first follow-up visit occurred at a median of 1.00 years (range 0.47 – 12.6; IQR 0.7 – 2.6 y), and the last follow-up visit occurred at a median of 4.65 years (range 0.5 – 17; IQR 2.4 – 7.8 y). The average age for FS and FA assessment were 2.4 years (range 0 – 12.6 y; IQR 0.82 – 3.11) and 4.9 years (range 0.5 – 17.0 y; IQR 2.1 – 7.0 y), respectively. Five hundred and seven children (36.4%) had food sensitization, 78 children (5.6%) were classified as “Confirmed/Convincing Food Allergy,” 45 (3.2%) as “Probable Food Allergy,” and 190 (13.6%) as “Possible Food Allergy” (Table 1). Children with food sensitization were more likely to be male, of Black race/ethnicity, have mothers who were non-smokers during pregnancy, and were assessed for food allergy at an older age than those without food sensitization. Children with “Confirmed/Convincing Food Allergy” were more likely to be male and have mothers who were atopic (Table 2).

Table 1:

Number of Children with FS and FA in the BBC Subcohort

| Cord Blood Subcohort (n=502) | Total Folate Cohort (n=1394) | |

|---|---|---|

| Food Sensitization (FS) Outcomes | ||

| Sensitized | 193 (38.5) | 507 (36.4) |

| Not Sensitized | 309 (61.6) | 887 (63.6) |

|

Food Allergy (FA) Outcomes | ||

| Not Sensitized and Not Allergic | 293 (58.4) | 845 (60.6) |

| Sensitized but Tolerant | 84 (16.7) | 229 (16.4) |

| Possible Food Allergy | 63 (12.6) | 190 (13.6) |

| Probable Food Allergy | 27 (5.4) | 45 (3.2) |

| Confirmed/Convincing | 33 (6.6) | 78 (5.6) |

| Unclassified | 2 (0.4) | 7 (0.5) |

Values expressed as n (%) unless otherwise noted

Table 2:

Characteristics of the Overall BBC Subcohort by FS and FA Outcomes

| Characteristic | Food Sensitization | Food Allergy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=507) | No (n=887) | p value | Yes (n=78) | No (n=1074) | p value | |

| Male | 290 (57.3) | 423 (47.7) | 0.001 | 51 (65.4) | 527 (49.1) | 0.006 |

| Age (yr)*‡ | 5.0 ± 0.14 | 4.9 ± 0.11 | 0.61 | 4.8 ± 0.37 | 5.0 ± 0.10 | 0. 67 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.001 | 0.07 | ||||

| Black | 336 (66.9) | 516 (58.4) | 56 (71.8) | 638 (59.7) | ||

| Hispanic | 98 (19.5) | 201 (22.8) | 16 (20.5) | 242 (22.6) | ||

| Caribbean | 23 (4.6) | 51 (5.8) | 1 (1.3) | 62 (5.8) | ||

| White | 10 (2.0) | 64 (7.3) | 1 (1.3) | 64 (6.0) | ||

| Asian | 9 (1.8) | 10 (1.1) | 2 (2.6) | 10 (0.9) | ||

| Other | 26 (5.2) | 41 (4.6) | 2 (2.6) | 53 (5.0) | ||

| Maternal Education | 1.0 | 0.31 | ||||

| Elementary School | 24 (4.8) | 42 (4.8) | 3 (3.9) | 56 (5.3) | ||

| Secondary School | 120 (23.9) | 210 (24.0) | 15 (19.5) | 252 (23.7) | ||

| High School/GED | 182 (36.3) | 315 (36.0) | 37 (48.1) | 380 (35.8) | ||

| Some College | 112 (22.3) | 199 (22.7) | 15 (19.5) | 238 (22.4) | ||

| College degree | 64 (12.8) | 110 (12.6) | 7 (9.1) | 136 (12.8) | ||

| Mode of Delivery | 0.54 | 0.06 | ||||

| Vaginal | 326 (64.4) | 570 (64.3) | 41 (52.6) | 706 (65.8) | ||

| C-Section | 177 (35.0) | 314 (35.4) | 37 (47.4) | 366 (34.1) | ||

| Premature birth )(<37w) | 107 (21.2) | 228 (25.8) | 0.06 | 15 (19.2) | 259 (24.2) | 0.32 |

| Infant Feeding | 0.25 | 0.93 | ||||

| Bottle | 112 (22.8) | 235 (26.7) | 20 (26.3) | 275 (25.9) | ||

| Breast | 38 (7.7) | 59 (6.7) | 6 (7.9) | 72 (6.8) | ||

| Both | 342 (69.5) | 586 (66.6) | 50 (65.8) | 714 (67.3) | ||

| Maternal Smoking | ||||||

| During pregnancy | 43 (8.6) | 99 (11.3) | 0.02 | 10 (12.8) | 112 (10.5) | 0.24 |

| After pregnancy | 74 (14.7) | 165 (18.7) | 0.16 | 19 (24.4) | 187 (17.5) | 0.30 |

| Maternal age (yr)*† | 28.8 ± 6.6 | 28.2 ± 6.3 | 0.07 | 29.1 ± 6.8 | 28.3 ± 6.3 | 0. 30 |

| Maternal Atopy | 143 (32.2) | 225 (28.6) | 0.19 | 28 (41.8) | 274 (28.8) | 0.02 |

Values expressed as n (%) unless otherwise noted

Mean ± SE

Age when food allergy assessment was made

Age at delivery

P values determined by Pearson chi-squared test or t-test

Within this subcohort, 502 children had UMFA and 5-MTHF concentrations measured in cord blood, 181 children had UMFA and 5-MTHF concentrations measured at 6 months to 3 years of age, and 863 children had total folate measured at 1–9 years of age. Compared to the overall subcohort and to the entire CHS population, the subcohort of children with cord blood measurements (n=502) had a lower proportion of preterm births (p<0.001) and fewer children of Black race/ethnicity (p<0.001), as demonstrated in Table E2. There was no difference in the proportion of FS or FA outcome classifications (Table 1).

Overview of folate measurements

At the time of birth, maternal total folate concentrations ranged from 6.6 to 185.5 (geometric mean 29.5; IQR 19.7 – 44.8) nmol/L, as shown in Table E3. Previously reported reference values for serum folate in the third trimester of pregnancy range from 3–47 nmol/L.(30) Cord blood 5-MTHF concentrations ranged from 1.77 to 314.7 (geometric mean 46.2; IQR 31.6 – 70.6) nmol/L, and UMFA concentrations ranged from 0 to 21.3 (geometric mean 0.83; IQR 0.45 – 1.57) nmol/L. UMFA was detected in 98.8% of children with cord blood measurements. Maternal total folate concentrations were minimally correlated with cord blood UMFA and 5-MTHF concentrations (r=0.11 and r=0.12, respectively) whereas UMFA and 5-MTHF concentrations were more strongly correlated (r=0.32).

In early childhood, total folate concentrations ranged from 9.9 to 91.2 (geometric mean 37.8; IQR 31.0 – 49.8) nmol/L. Previously reported plasma folate reference ranges for children are 11.3 – 47.6 nmol/L.(31) Peripheral blood 5-MTHF concentrations ranged from 8.7 to 101.9 (geometric mean 41.1; IQR 30.9 – 61.8) nmol/L, and UMFA concentrations ranged from 0 to 22.2 (geometric mean 0.56; IQR 0.23 – 1.39) nmol/L. Similar to cord blood, UMFA was detected in 98.9% of early childhood samples. Early childhood total folate, UMFA, 5-MTHF concentrations were strongly correlated (Table E3).

Associations between maternal total folate and the development of FS and FA

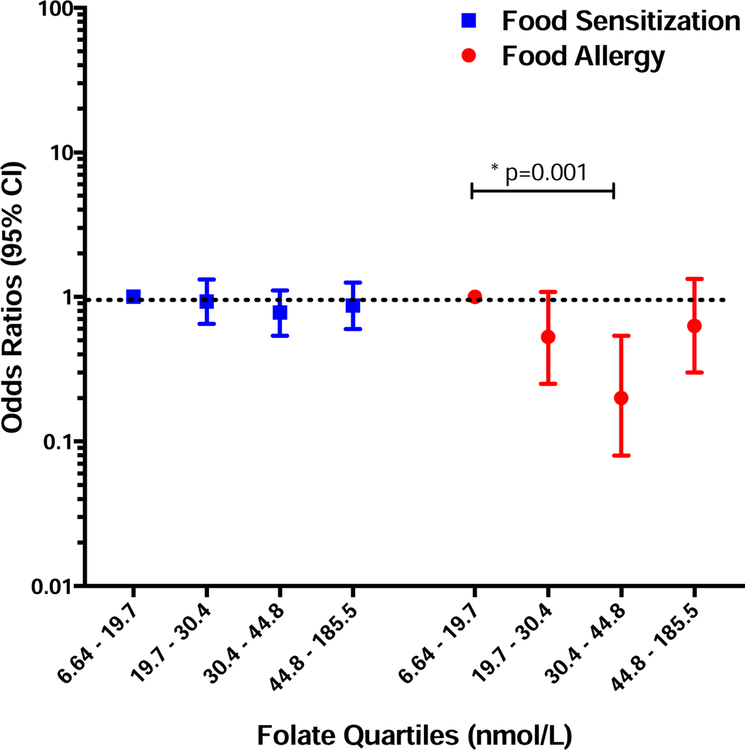

Maternal total folate concentrations at the time of delivery were similar among those children who did and did not develop FS (mean 35.3; SE 1.1 v. mean 35.6; SE 0.8 nmol/L; p=0.32). Furthermore, when total folate concentrations were divided into quartiles, there was no association between increasing quartiles of maternal total folate and FS in adjusted multiple logistic regression models (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Associations between Maternal Total Folate and FS/FA.

Odds ratios of food sensitization (blue) and food allergy (red) for increasing quartiles of maternal total folate measured in plasma at the time of birth. Bars and whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals (CI) and the dotted line depicts the null hypothesis (OR=1). Multivariable models adjusted for maternal age, race, maternal education, maternal BMI, maternal history of atopy, pre-natal and post-natal maternal smoking, child’s gender, mode of delivery, breastfeeding history, child’s age when specific food IgE was measured, and child’s age when clinical symptoms on food ingestion was assessed (for FA).

In contrast, maternal total folate concentrations were lower among those whose children later developed FA (mean 30.2; SE 2.2 v. mean 35.3; SE 0.7 nmol/L; p=0.02). When folate concentrations were divided into quartiles, a non-linear relationship was seen. Children whose mothers had total folate concentrations in the third quartile (30.4 – 44.8 nmol/L) had a lower odds of developing food allergy than those in the first (6.64 – 19.7 nmol/L) quartile (p=0.001), as shown in Figure 1. This relationship persisted in the sensitivity analyses including only children who had sIgE and clinical food allergy assessments prior to age 5 (OR 0.10; 95% CI 0.02–0.50; p<0.01). However, it did not persist when including those with “Probable” and “Possible” food allergy outcomes in the analysis (OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.49–1.14; p=0.18).

Higher cord blood UMFA concentrations are a risk factor for the development of FA

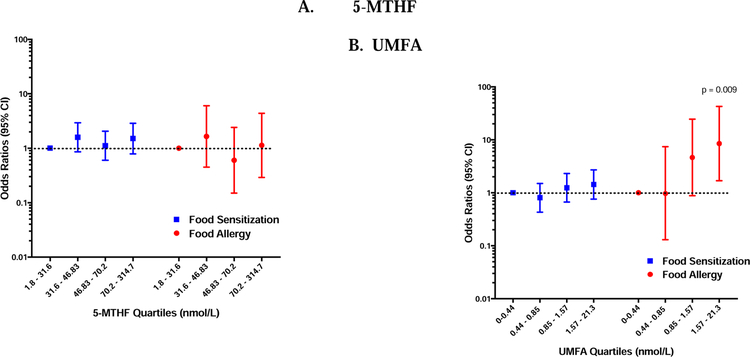

Mean cord blood UMFA concentrations were similar among children with and without FS (mean 1.45 nmol/L; SE 0.14 versus mean 1.35; SE 0.11; p= 0.42), and there was no association seen between increasing quartiles of UMFA concentrations and FS in multiple logistic regression models (Figure 2). However, in sensitivity analyses examining a higher threshold for sIgE (0.7 kU/L), increasing quartiles of UMFA were associated with FS (OR 2.41; 95% CI 1.19–4.88; p=0.01). This trend persisted when examining the highest threshold for sIgE (0.35 kU/L), though this did not meet the Bonferroni-corrected level of significance (OR 3.55; 95% CI 1.13–11.1; p=0.03, Figure E2).

Figure 2: Associations between Cord Blood Folate Metabolites and FS/FA.

Odds ratios of food sensitization (blue) and food allergy (red) for increasing quartiles of 5-MTHF (A) and UMFA (B) measured in cord blood at the time of birth, generated from multivariable logistic regression models. Bars and whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals (CI) and the dotted line depicts the null hypothesis (OR=1). Test for trend p=0.001.

Similarly, cord blood UMFA concentrations were higher among those who developed FA (1.72 nmol/L; SE 0.22 v. 1.30; SE 0.10; p=0.001), and increasing quartiles of cord blood UMFA concentrations was associated with an increased odds of developing FA in a dose-response manner (test for trend p value = 0.001, Figure 2). This relationship persisted when adjusting for cord blood 5-MTHF concentrations, suggesting an independent effect of high cord blood UMFA concentrations on the development of FA (Table 3). Furthermore, this relationship persisted when including those with “Probable and “Possible” food allergy outcomes in the analysis (Figure E2). A similar relationship was seen when only including those with sIgE and FA assessments prior to age 5 (Figure E2), but this was not statistically significant. No association was seen between cord blood 5-MTHF concentrations and the development of FS or FA (Figure 2).

Table 3:

Independent Association between Cord Blood UMFA and Food Allergy

| Unadjusted* | Adjusting for Cord Blood 5-MTHF§ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | Non-FA | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| UMFA | ||||||

| Quartile 1 | 4 | 99 | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Quartile 2 | 4 | 101 | 0.97 (0.13 – 7.38) | 0.98 | 1.04 (0.13 – 8.26) | 0.97 |

| Quartile 3 | 11 | 90 | 4.64 (0.88 – 24.5) | 0.07 | 6.22 (1.13 – 34.36 | 0.04 |

| Quartile 4 | 14 | 87 | 8.51 (1.69 – 42.8) | 0.009 | 14.9 (2.7 0 – 82.5) | 0.002 |

Values expressed as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Multiple logistic regression models not adjusted for cord blood 5-MTHF levels (n=288)

Multiple logistic regression models adjusted for log-transformed cord blood 5-MTHF levels (n=288)

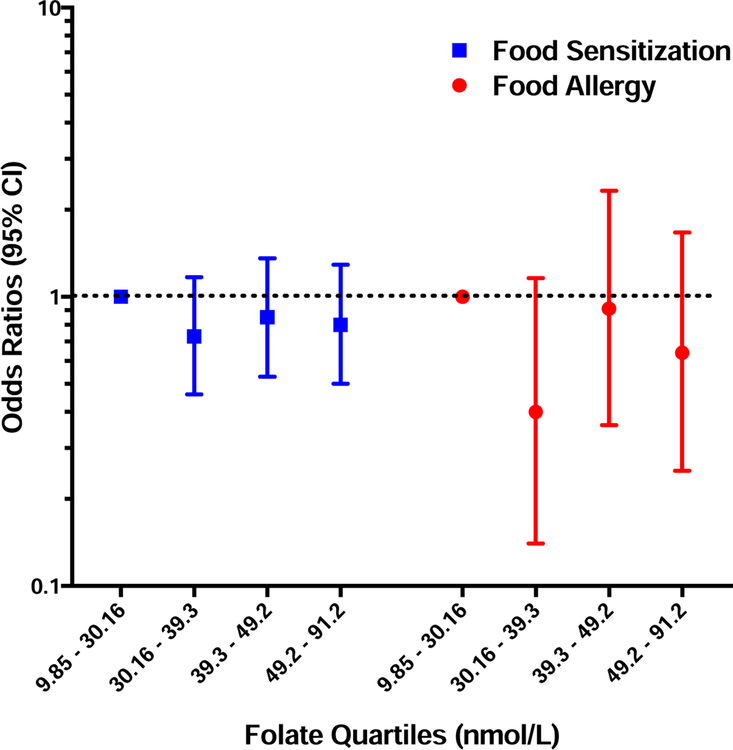

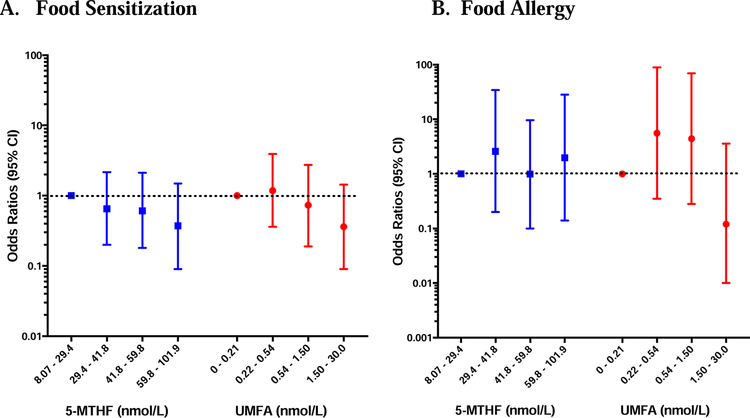

Total Folate, UMFA and 5-MTHF concentrations in early childhood are not associated with the development of either FS or FA.

In multiple logistic regression models, no association was seen between total folate, 5-MTHF, or UMFA concentrations measured in child’s serum in early childhood and the development of FS or FA (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Associations between Early Childhood Total Folate and FS/FA.

Odds ratios of food sensitization (blue) and food allergy (red) for increasing quartiles of total folate measured in children’s peripheral blood in early childhood (1 to 9 years). Odds ratios were generated by multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for maternal age, race, maternal education, maternal BMI, maternal history of atopy, pre-natal and post-natal maternal smoking, child’s gender, mode of delivery, breastfeeding history, child’s age when specific food IgE was measured, and child’s age when clinical symptoms on food ingestion was assessed (for FA). Bars and whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals (CI) and the dotted line depicts the null hypothesis (OR=1).

Figure 4: Associations between Early Childhood Folate Metabolites and FS/FA.

Odds ratios of food sensitization (A) and food allergy (B) for increasing quartiles of 5-MTHF (blue) and UMFA (red) measured in children’s peripheral blood in early childhood (6 months to 3 years), generated from multivariable logistic regression models. Bars and whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals (CI) and the dotted line depicts the null hypothesis (OR=1).

Associations with prenatal folic acid intake

The number of women taking prenatal folic acid supplements in the BBC subcohort increased from 6.8% prior to pregnancy to 90.6% in the first trimester, 95.3% in the second trimester, and 93.8% in the third trimester. Cord blood UMFA and 5-MTHF concentrations were higher among women who took folic acid supplements in the second and third trimesters (p<0.01 for all). In multiple logistic regression models, however, prenatal folic acid supplement use was not associated with the development of FS or FA in any trimester (data not shown).

Discussion

In this case-control study nested within the prospective, observational, predominantly urban minority Boston Birth Cohort, we found that while mean total folate concentrations at birth were lower among those who developed food allergy, higher concentrations of unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA) in cord blood were associated with an increased risk for the subsequent development of this condition. We further found that neither 5-MTHF nor UMFA in early or later childhood were associated with an increased risk for the development of food allergy. While other studies have examined the association between folate and atopic conditions, this is the first study to explore the association with the specific forms of folate: 5-MTHF and UMFA. In addition, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the longitudinal risk of UMFA exposure on the development of food allergy in the United States, where mandatory folic acid fortification has been in place for two decades. As UMFA is uniquely derived from synthetic folic acid, our findings suggest there may be unintended consequences from widespread folic acid fortification and prenatal supplementation in recent years.(32)

The question of whether folate is a risk factor for the development of allergic disease has been assessed in multiple observational studies, which have yielded conflicting results. While some studies have found that higher folate intake in late pregnancy is a risk factor for the subsequent development of asthma and eczema,(13, 33, 34) other studies have not seen such an association.(11, 35) These studies differ widely in terms of exposure classification, allergic outcomes assessed, timing of folate assessment, and national guidelines for folic acid fortification, which may contribute to the conflicting results.

When specifically examining folic acid supplementation during pregnancy, Whitrow et al first demonstrated that supplemental folic acid use in late pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of asthma in the offspring in 2009.(13) Similar associations have since been seen with wheezing in the first year of life,(16) asthma medication use,(18) eczema,(36) and cow’s milk allergy.(15) Interestingly, such an association was not seen when examining folic acid use in the first trimester of pregnancy,(37, 38) when folate is essential to prevent the development of neural tube defects. To date, no randomized, controlled trials have assessed the risk of folic acid supplementation in late pregnancy on the development of allergic disease.

Unmetabolized folic acid (UMFA) appears in the circulation when the enzyme that converts folic acid to tetrahydrofolate (dihydrofolate reductase [DHFR]) is saturated. This has been shown to occur at a folic acid intake of approximately 250ug in most individuals,(19) though this threshold may be influenced by a functional 19 base-pair deletion in the gene DHFR(39) which has a prevalence of approximately 20% in the general population and is more prevalent in African Americans.(40) In the United States, the CDC, ACOG, and AAP recommend that all women of reproductive age take 400 ug of folic acid a day prior to conception and throughout pregnancy to reduce their risk of having a child with a neural tube defect, and women at high risk are instructed to take up to 4000 ug daily through the first trimester.(41–43) In addition, mandatory fortification of flour, breads, cereals, and rice with folic acid was implemented in the United States in 1998, and as a result, a recent cross-sectional survey demonstrated that greater than 95% of Americans have detectable UMFA in peripheral blood,(21) which is consistent with our findings. Studies conducted in other countries with mandatory or voluntary folic acid fortification have similarly demonstrated detectable UMFA in the cord blood and peripheral blood of newborns,(44–47) peripheral blood of adults and pregnant women,(44, 45, 47, 48) and the breast milk of lactating women.(49) To date, studies examining the association between UMFA and adverse health outcomes are limited,(32) and this is the first study to examine this relationship with the development of food allergy.

While the exact biologic mechanism of action, if any, for UMFA is unknown, it has been shown that two of the three folate transport systems have a high affinity for UMFA.(50) A recent study further demonstrated that the presence of UMFA may impair update of 5-MTHF in umbilical endothelial cells.(51) As circulating 5-MTHF is the principle source of cellular folate involved in DNA synthesis and methylation, selective transport of UMFA instead of 5-MTHF may decrease intracellular folate stores, leading to disruptions in these processes. Regulatory T cells have been shown to express a high affinity folate receptor (FR4),(52, 53) which is essential for their survival,(54) so this imbalance may be particularly important for the development of allergic diseases. Interestingly, a recent cross-sectional study found an inverse correlation between FoxP3 expression in peripheral T regulatory cells and serum folate concentrations that was more pronounced among allergic children.(55) Alternatively, higher UMFA concentrations have been associated with decreased NK cell cytotoxicity,(56, 57) and a recent randomized controlled trial of high-dose folic acid supplementation additionally demonstrated elevated IL-8 and TNF-alpha expression after high dose folic acid supplementation.(58) While this may not be consistent with immunologic alterations typically seen in allergic disease, alterations in Th2 cytokines have, to our knowledge, not yet been examined.

In this study, we also found a non-linear relationship between total folate concentrations measured in maternal plasma at the time of birth and the subsequent development of food allergy, where the lowest risk was seen with maternal folate concentrations in the third quartile (30.4 – 44.8 nmol/L). These results are similar to previous findings by Dunstan et al, in which a “U-shaped” relationship was seen between cord blood total folate and the development of allergic sensitization in an Australian birth cohort, with the lowest risk being among those with folate concentrations of 50 – 75 nmol/L.(34) While these protective folate ranges are not exactly comparable between the two studies, this may be due to the fact that folate concentrations are typically higher in fetal than maternal blood.(34, 47) A protective effect for folate exposure in mid to late pregnancy and the development of allergic disease has similarly been reported in three additional studies.(59–61) While our findings for maternal total folate and cord blood UMFA are seemingly contradictory, UMFA only represents a small percentage of circulating total folate and is uniquely derived from synthetic folic acid intake. Recent studies suggest that a strong association between UMFA and serum total folate levels only occurs when total folate levels are high (>78.5 nmol/L),(62) and thus further research regarding the determinants of each of these folate measurements is clearly needed.

Our study is limited by the fact that this is an observational study, and thus there is the possibility of unmeasured confounders that may influence the association seen between folate forms and food allergy. It is possible, for example, that differences in the gut microbiome, pet exposure, or behaviors associated with higher socioeconomic status may ultimately explain our findings. Our study is additionally limited by the fact that food allergy is only reliably diagnosed through oral food challenges, and because these were only performed as clinically indicated outside of this study, there is the potential for outcome misclassification. Our study is further limited by the fact that we were only able to measure folate metabolites at the end of pregnancy rather than in the first and second trimesters. Thus, we are unable to determine the exact timing of risk during pregnancy. While this would be helpful information for designing future intervention studies, adequate folate in the first trimester is essential for the prevention of neural tube defects in the offspring, and thus it would be unethical to propose a future study limiting folic acid exposure during this time in pregnancy. In addition, our study is limited by inadequate information on dietary and supplement intake of folate during pregnancy. While this does not negate the association seen between cord blood UMFA and food allergy, it may be an additional confounder in the relationship between folate exposure and food allergy. Furthermore, while total folate concentrations were strongly associated with UMFA and 5-MTHF concentrations in early childhood, we surprisingly did not see this at birth, and thus these findings should be replicated in further studies. Finally, the BBC is predominantly composed of individuals of non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity (a population with higher prevalence of DHFR deletion), and thus our findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

In conclusion, in this case-control study nested within the Boston Birth Cohort, we found that higher concentrations of UMFA in cord blood, but not in childhood, were associated with an increased risk for the development of food allergy. This novel finding raises the question of whether there are unintended consequences from widespread folic acid fortification and prenatal supplementation in recent decades. Further studies are needed to validate these findings in other populations, investigate the role of genetic polymorphisms in this relationship, and examine the mechanism of action of UMFA on developing immune cells.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

What is already known about this topic? Folate exposure has been proposed as a risk factor for the development of allergic disease. UMFA is uniquely derived from synthetic folic acid exposure, and 5-MTHF is the principal folate form involved in DNA methylation.

What does this article add to our knowledge? This is the first study to examine the association between UMFA/5-MTHF and the development of food allergy. We found that higher concentrations of UMFA at birth were associated with the development of food allergy.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? Our findings suggest there may be unintended consequences from widespread folic acid fortification and supplementation in recent decades. However, whether this is due to increased exposure to folic acid or underlying genetic differences remains unknown.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was funded by the NIH through the following grants: 1KL2TR001077, K23AI123596, R01ES026170, R01ES023447, K24AI114769, and by the AAAAI/FARE/Howard Gittis Junior Faculty Research Award. The Boston Birth Cohort (the parent study) was supported in part by grants from the Bunning Family and their family foundations, Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U01AI090727 from the Consortium of Food Allergy Research, and R21AI088609).

Abbreviations used:

- BBC

Boston Birth Cohort

- IgE

Immunoglobulin E

- FS

Food sensitization

- FA

Food allergy

- UMFA

Unmetabolized folic acid

- 5-MTHF

5-methyltetrahydrofolate

- IQR

Interquartile range

- SE

Standard Error

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: E. McGowan has received grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI), and Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE), and served as a consultant for Shire, Inc. R.A. Wood has received grants from the NIH, DBV, Aimmune, Astella, and HAL-Allergy; has consultant arrangements with Stallergenes; is employed by Johns Hopkins University; and receives royalties from UpToDate. E.C. Matsui receives grant support from the NIH; serves as a consultant for Environmental Defense Fund, Church, & Dwight, LLC; and has received payment for lectures from Indoor Biotechnologies. C.A. Keet receives grant support from the NIH and is the co-owner of Skybrude Consulting, LLC. X. Wang, X Hong, J. Selhub, and L. Paul have received grant support from the NIH.

Contributor Information

Emily C. McGowan, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Division of Allergy and Immunology, Charlottesville, VA. Adjunct Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Baltimore, MD.

Xiumei Hong, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Population, Family, and Reproductive Health, Center on the Early Life Origins of Disease, Baltimore, MD.

Jacob Selhub, Tufts University, JM USDA HNRCA at Tufts University, Boston, MA.

Ligi Paul, Tufts University, JM USDA HNRCA at Tufts University, Boston, MA.

Robert A. Wood, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, Baltimore, MD.

Elizabeth C. Matsui, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, Baltimore, MD.

Corinne A. Keet, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology.

Xiaobin Wang, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Population, Family, and Reproductive Health, Center on the Early Life Origins of Disease, Baltimore, MD.

References

- 1.Flokstra-de Blok BM, van der Velde JL, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Oude Elberink JN, DunnGalvin A, Hourihane JO, et al. Health-related quality of life of food allergic patients measured with generic and disease-specific questionnaires. Allergy 2010;65(8):1031–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venter C, Hasan Arshad S, Grundy J, Pereira B, Bernie Clayton C, Voigt K, et al. Time trends in the prevalence of peanut allergy: three cohorts of children from the same geographical location in the UK. Allergy 2010;65(1):103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson KD, Howie LD, Akinbami LJ. Trends in allergic conditions among children: United States, 1997–2011. NCHS Data Brief 2013(121):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martino D, Joo JE, Sexton-Oates A, Dang T, Allen K, Saffery R, et al. Epigenome-wide association study reveals longitudinally stable DNA methylation differences in CD4+ T cells from children with IgE-mediated food allergy. Epigenetics 2014;9(7):998–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang IV, Pedersen BS, Liu A, O’Connor GT, Teach SJ, Kattan M, et al. DNA methylation and childhood asthma in the inner city. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136(1):69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czeizel AE, Dudas I. Prevention of the first occurrence of neural-tube defects by periconceptional vitamin supplementation. N Engl J Med 1992;327(26):1832–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Lancet 1991;338(8760):131–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentley TG, Willett WC, Weinstein MC, Kuntz KM. Population-level changes in folate intake by age, gender, and race/ethnicity after folic acid fortification. Am J Public Health 2006;96(11):2040–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietrich M, Brown CJ, Block G. The effect of folate fortification of cereal-grain products on blood folate status, dietary folate intake, and dietary folate sources among adult non-supplement users in the United States. J Am Coll Nutr 2005;24(4):266–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McStay CL, Prescott SL, Bower C, Palmer DJ. Maternal Folic Acid Supplementation during Pregnancy and Childhood Allergic Disease Outcomes: A Question of Timing? Nutrients 2017;9(2). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haberg SE, London SJ, Stigum H, Nafstad P, Nystad W. Folic acid supplements in pregnancy and early childhood respiratory health. Arch Dis Child 2009;94(3):180–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veeranki SP, Gebretsadik T, Mitchel EF, Tylavsky FA, Hartert TV, Cooper WO, et al. Maternal Folic Acid Supplementation During Pregnancy and Early Childhood Asthma. Epidemiology 2015;26(6):934–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitrow MJ, Moore VM, Rumbold AR, Davies MJ. Effect of supplemental folic acid in pregnancy on childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170(12):1486–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parr CL, Magnus MC, Karlstad O, Haugen M, Refsum H, Ueland PM, et al. Maternal Folate Intake during Pregnancy and Childhood Asthma in a Population-based Cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195(2):221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuokkola J, Luukkainen P, Kaila M, Takkinen HM, Niinisto S, Veijola R, et al. Maternal dietary folate, folic acid and vitamin D intakes during pregnancy and lactation and the risk of cows’ milk allergy in the offspring. The British journal of nutrition 2016;116(4):710–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bekkers MB, Elstgeest LE, Scholtens S, Haveman-Nies A, de Jongste JC, Kerkhof M, et al. Maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy, and childhood respiratory health and atopy. The European respiratory journal 2012;39(6):1468–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, Jiang L, Bi M, Jia X, Wang Y, He C, et al. High dose of maternal folic acid supplementation is associated to infant asthma. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2015;75:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zetstra-van der Woude PA, De Walle HE, Hoek A, Bos HJ, Boezen HM, Koppelman GH, et al. Maternal high-dose folic acid during pregnancy and asthma medication in the offspring. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2014;23(10):1059–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly P, McPartlin J, Goggins M, Weir DG, Scott JM. Unmetabolized folic acid in serum: acute studies in subjects consuming fortified food and supplements. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65(6):1790–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalmbach RD, Choumenkovitch SF, Troen AM, D’Agostino R, Jacques PF, Selhub J. Circulating folic acid in plasma: relation to folic acid fortification. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88(3):763–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeiffer CM, Sternberg MR, Fazili Z, Yetley EA, Lacher DA, Bailey RL, et al. Unmetabolized folic acid is detected in nearly all serum samples from US children, adolescents, and adults. J Nutr 2015;145(3):520–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar R, Ouyang F, Story RE, Pongracic JA, Hong X, Wang G, et al. Gestational diabetes, atopic dermatitis, and allergen sensitization in early childhood. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2009;124(5):1031–8 e1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Zuckerman B, Pearson C, Kaufman G, Chen C, Wang G, et al. Maternal cigarette smoking, metabolic gene polymorphism, and infant birth weight. Jama 2002;287(2):195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang G, Hu FB, Mistry KB, Zhang C, Ren F, Huo Y, et al. Association Between Maternal Prepregnancy Body Mass Index and Plasma Folate Concentrations With Child Metabolic Health. JAMA pediatrics 2016;170(8):e160845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fazili Z, Whitehead RD Jr., Paladugula N, Pfeiffer CM A high-throughput LC-MS/MS method suitable for population biomonitoring measures five serum folate vitamers and one oxidation product. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2013;405(13):4549–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fazili Z, Pfeiffer CM, Zhang M. Comparison of serum folate species analyzed by LC-MS/MS with total folate measured by microbiologic assay and Bio-Rad radioassay. Clin Chem 2007;53(4):781–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Midttun O, Townsend MK, Nygard O, Tworoger SS, Brennan P, Johansson M, et al. Most blood biomarkers related to vitamin status, one-carbon metabolism, and the kynurenine pathway show adequate preanalytical stability and within-person reproducibility to allow assessment of exposure or nutritional status in healthy women and cardiovascular patients. J Nutr 2014;144(5):784–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong X, Wang G, Liu X, Kumar R, Tsai HJ, Arguelles L, et al. Gene polymorphisms, breast-feeding, and development of food sensitization in early childhood. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2011;128(2):374–81 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong X, Liang L, Sun Q, Keet C, Tsai HJ, Ji Y, et al. Maternal Triacylglycerol Signature and Offspring Risk of Food Allergy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Abbassi-Ghanavati M, Greer LG, Cunningham FG. Pregnancy and laboratory studies: a reference table for clinicians. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114(6):1326–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fishbach FDM. Manual of laboratory and diagnostic tests, 9th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selhub J, Rosenberg IH. Excessive folic acid intake and relation to adverse health outcome. Biochimie 2016;126:71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haberg SE, London SJ, Nafstad P, Nilsen RM, Ueland PM, Vollset SE, et al. Maternal folate levels in pregnancy and asthma in children at age 3 years. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2011;127(1):262–4, 4 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunstan JA, West C, McCarthy S, Metcalfe J, Meldrum S, Oddy WH, et al. The relationship between maternal folate status in pregnancy, cord blood folate levels, and allergic outcomes in early childhood. Allergy 2012;67(1):50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Granell R, Heron J, Lewis S, Davey Smith G, Sterne JA, Henderson J. The association between mother and child MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, dietary folate intake and childhood atopy in a population-based, longitudinal birth cohort. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38(2):320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunstan JA, West C, McCarthy S, Metcalfe J, Meldrum S, Oddy WH, et al. The relationship between maternal folate status in pregnancy, cord blood folate levels, and allergic outcomes in early childhood Folic acid use in pregnancy and the development of atopy, asthma, and lung function in childhood Study of folate status among Egyptian asthmatics Maternal folate levels in pregnancy and asthma in children at age 3 years. Allergy 2012;67(1):50–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinussen MP, Risnes KR, Jacobsen GW, Bracken MB. Folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy and asthma in children aged 6 years. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2012;206(1):72 e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Granell R, Heron J, Lewis S, Davey Smith G, Sterne JA, Henderson J, et al. The association between mother and child MTHFR C677T polymorphisms, dietary folate intake and childhood atopy in a population-based, longitudinal birth cohort The association between atopy and factors influencing folate metabolism: is low folate status causally related to the development of atopy? Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38(2):320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalmbach RD, Choumenkovitch SF, Troen AP, Jacques PF, D’Agostino R, Selhub J. A 19-base pair deletion polymorphism in dihydrofolate reductase is associated with increased unmetabolized folic acid in plasma and decreased red blood cell folate. J Nutr 2008;138(12):2323–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Philip D, Buch A, Moorthy D, Scott TM, Parnell LD, Lai CQ, et al. Dihydrofolate reductase 19-bp deletion polymorphism modifies the association of folate status with memory in a cross-sectional multi-ethnic study of adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102(5):1279–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Use of folic acid for prevention of spina bifida and other neural tube defects−−1983–1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1991;40(30):513–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheschier N ACOG practice bulletin. Neural tube defects. Number 44, July 2003. (Replaces committee opinion number 252, March 2001). Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;83(1):123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Genetics. Pediatrics 1999;104(2 Pt 1):325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sweeney MR, Staines A, Daly L, Traynor A, Daly S, Bailey SW, et al. Persistent circulating unmetabolised folic acid in a setting of liberal voluntary folic acid fortification. Implications for further mandatory fortification? BMC Public Health 2009;9:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Obeid R, Kasoha M, Kirsch SH, Munz W, Herrmann W. Concentrations of unmetabolized folic acid and primary folate forms in pregnant women at delivery and in umbilical cord blood. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92(6):1416–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sweeney MR, McPartlin J, Weir DG, Daly S, Pentieva K, Daly L, et al. Evidence of unmetabolised folic acid in cord blood of newborn and serum of 4-day-old infants. The British journal of nutrition 2005;94(5):727–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plumptre L, Masih SP, Ly A, Aufreiter S, Sohn KJ, Croxford R, et al. High concentrations of folate and unmetabolized folic acid in a cohort of pregnant Canadian women and umbilical cord blood. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102(4):848–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boilson A, Staines A, Kelleher CC, Daly L, Shirley I, Shrivastava A, et al. Unmetabolized folic acid prevalence is widespread in the older Irish population despite the lack of a mandatory fortification program. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96(3):613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Page R, Robichaud A, Arbuckle TE, Fraser WD, MacFarlane AJ. Total folate and unmetabolized folic acid in the breast milk of a cross-section of Canadian women. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105(5):1101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao R, Diop-Bove N, Visentin M, Goldman ID. Mechanisms of membrane transport of folates into cells and across epithelia. Annu Rev Nutr 2011;31:177–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith D, Hornstra J, Rocha M, Jansen G, Assaraf Y, Lasry I, et al. Folic Acid Impairs the Uptake of 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate in Human Umbilical Vascular Endothelial Cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2017;70(4):271–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamaguchi T, Hirota K, Nagahama K, Ohkawa K, Takahashi T, Nomura T, et al. Control of immune responses by antigen-specific regulatory T cells expressing the folate receptor. Immunity 2007;27(1):145–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tian Y, Wu G, Xing JC, Tang J, Zhang Y, Huang ZM, et al. A novel splice variant of folate receptor 4 predominantly expressed in regulatory T cells. BMC Immunol 2012;13:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kunisawa J, Hashimoto E, Ishikawa I, Kiyono H. A pivotal role of vitamin B9 in the maintenance of regulatory T cells in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2012;7(2):e32094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Socha-Banasiak A, Kamer B, Gach A, Wysocka U, Jakubowski L, Glowacka E, et al. Folate status, regulatory T cells and MTHFR C677T polymorphism study in allergic children. Adv Med Sci 2016;61(2):300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Troen AM, Mitchell B, Sorensen B, Wener MH, Johnston A, Wood B, et al. Unmetabolized folic acid in plasma is associated with reduced natural killer cell cytotoxicity among postmenopausal women High folic acid intake reduces natural killer cell cytotoxicity in aged mice. J Nutr 2006;136(1):189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sawaengsri H, Wang J, Reginaldo C, Steluti J, Wu D, Meydani SN, et al. High folic acid intake reduces natural killer cell cytotoxicity in aged mice. J Nutr Biochem 2016;30:102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paniz C, Bertinato JF, Lucena MR, De Carli E, Amorim P, Gomes GW, et al. A Daily Dose of 5 mg Folic Acid for 90 Days Is Associated with Increased Serum Unmetabolized Folic Acid and Reduced Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity in Healthy Brazilian Adults. J Nutr 2017;147(9):1677–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Magdelijns FJ, Mommers M, Penders J, Smits L, Thijs C. Folic acid use in pregnancy and the development of atopy, asthma, and lung function in childhood. Pediatrics 2011;128(1):e135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim JH, Jeong KS, Ha EH, Park H, Ha M, Hong YC, et al. Relationship between prenatal and postnatal exposures to folate and risks of allergic and respiratory diseases in early childhood. Pediatr Pulmonol 2015;50(2):155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roy A, Kocak M, Hartman TJ, Vereen S, Adgent M, Piyathilake C, et al. Association of prenatal folate status with early childhood wheeze and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Stamm RA, March KM, Karakochuk CD, Gray AR, Brown RC, Green TJ, et al. Lactating Canadian Women Consuming 1000 microg Folic Acid Daily Have High Circulating Serum Folic Acid Above a Threshold Concentration of Serum Total Folate. J Nutr 2018;148(7):1103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.