Abstract

Objective:

To examine children’s unmet and unrecognized health care and school needs following traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Setting:

Two pediatric trauma centers

Participants:

Children with all severity TBI aged 4–15 years.

Design:

Prospective cohort

Main measures:

Caregivers provided child health and school service use three and 12-months post-injury. Unmet and unrecognized needs were categorized compared to norms on standardized physical, cognitive, socioemotional health, or academic competence measures in conjunction with caregiver report of needs and services. Modified Poisson models examined child and family predictors of unmet and unrecognized needs.

Results:

Of 322 children, 28% had unmet or unrecognized health care or school needs at three months decreasing to 24% at 12 months. Unmet health care needs changed from primarily physical (79%) at 3 months to cognitive (47%) and/or socioemotional (68%) at 12-months. At 3 months, low social capital, pre-existing psychological diagnoses and age 6–11 years predicted higher health care and severe TBI predicted higher school needs. Twelve months post-injury, prior inpatient rehabilitation, low income and pre-existing psychological diagnoses were associated with higher health care needs; family function was important for school and health care needs.

Conclusions:

Targeted interventions to provide family supports may increase children’s access to services.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, pediatrics, health services, rehabilitation

Introduction

Children with traumatic brain injury (TBI) may need post-injury medical and school services to reintegrate into home, school and community life. Children may have cognitive, emotional and behavioral issues after TBI that last from months to years and adversely affect health-related quality of life.1,2 Inpatient and outpatient rehabilitative services after TBI are helpful to children but are unevenly available.3,4 Physicians report difficulties in referring children for cognitive and behavioral services due to patient insurance limitations and limited availability of providers.5 While schools are required to provide services for children with TBI under the Individuals with Disability Education Act (IDEA),6 schools may not have the resources to identify children in need of services, may be unaware of the TBI, or may be unable to provide them appropriate academic or health care supports.7–9

Over a decade ago, Slomine et al. reported on the unmet and unrecognized health care needs of over 300 children hospitalized at least overnight for TBI.10 These investigators found that approximately one quarter of children had either an unmet or unrecognized health care need with the most need in the less severely injured group. Since that time, societal awareness of the possible consequences of TBI has increased as seen by articles in the lay press, published statements from medical societies, and systematic reviews of the evidence.11–14 In 2002, the CDC launched its “Heads Up” campaign designed to raise awareness and provide treatment recommendations to health care and school professionals caring for children with TBI.15 Recently, Fuentes documented unmet health care needs among hospitalized children 8 years and older with TBI two years after injury. This study reported higher unmet needs in children with less severe injury across multiple service types, and persisting unmet needs among all children with TBI suggesting that increased awareness of TBI consequences has not changed children’s ability to access care.16

Our goal was to characterize both health care and school service unmet and unrecognized needs of a contemporary cohort of children with all severities of TBI in the year following injury. We hypothesized that there would be an identifiable group of children with unmet and unrecognized health care and school needs.

Methods

Patient population

Patients were children with TBI injured between 4 to 15 years of age, recruited from two level 1 pediatric trauma centers, Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City, UT and University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston for the Children’s Development after TBI study.1 Families were approached in the Emergency Department (ED), hospital wards, or telephoned shortly after injury and asked for consent and assent. Children were excluded if they had a history of developmental delay or psychiatric diagnosis requiring a closed classroom because of the difficulty in assessing whether outcomes for this group were associated with the TBI. The Institutional Review Boards of both institutions approved the study protocol. Families completed a baseline survey about the child’s pre-injury status as soon as possible after injury (preinjury survey), and then completed three and 12-month interviews. Children with TBI were recruited according to age group and injury severity. TBI severity was measured using the lowest ED Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and categorized as: mild (GCS 13–15), moderate (GCS 9–12) and severe (GCS ≤8).17,18 Supplemental Figure 1. Mild TBI was subclassified as complicated mild dependent on the presence of an intracranial hemorrhage diagnosed on CT scan. Complicated mild and moderate TBI were combined for analysis as their outcomes were similar in prior studies.19

Data sources

Demographic information from the pre-injury survey included: family composition, self-identified race and ethnicity, family income category, caregiver education and employment, and health insurance status. Data were collected about pre-injury physician or school diagnoses of psychological problems (anxiety, attention, depression, developmental delay, behavioral or learning problems) and use of educational services including 504 accommodations and special education. Caregivers retrospectively completed pre-injury measures of the family environment including: the McMaster Family Assessment Device measures family functioning; and, the Social Capital Index, a measure of a person’s connectedness to their community including neighborhood and spiritual communities.20,21 Health care utilization, school services and follow-up assessments were collected prospectively at three months (recalling time of injury to interview) and 12 months (recalling past 6 months) after injury. English speaking families completed assessments in person, on-line or by telephone. Spanish speaking families completed assessments in person or by telephone with bilingual study coordinators. CT scans were performed for clinical indication only and were read by pediatric neuroradiologists at each site. CT reports were used to sub-classify the mild TBI children.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures included measures of physical, cognitive and socioemotional health and academic outcomes. Physical health was measured with the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) using the physical functioning, bodily pain/discomfort and role limitations questions.22 Cognitive health was measured with the Behavioral Rating Index of Executive Function (BRIEF, age ≥5 years) or BRIEF preschool version (BRIEF-P, age <5 years) Metacognition Indices (mean 50, SD 10).23,24 Socioemotional health was measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) Total Difficulties score.25 Z-scores were calculated from published norms for the CHQ and SDQ to facilitate comparisons. Academic outcomes were measured in children ≥6 years using the CBCL Academic Competence Scale.26

Health care and school services

At the three and 12-months interviews, caregivers reported the number and types of health care and school services that their child received. Caregivers were provided lists of potential health care providers and school service types or could enter free-text which was categorized by investigators. Health care utilization was divided into three types: physical, cognitive and socioemotional. Because providers can deliver more than one health care type, providers were placed into one or more categories as follows: physical health care included emergency department and hospital admissions, specialist and primary care physicians and nurse practitioners (NP), dentists, and occupational (OT), physical (PT) and speech language pathologists (SLP); cognitive health care included OT, SLP and neuropsychology; socioemotional health included pediatricians, family doctors, psychiatrists, psychologists, neuropsychologists, social workers and counselors. Primary care doctors are included in socioemotional health as they frequently provide behavioral health care.27 Potential school services included tutoring, 504 accommodations, homebound services and special education services (individual education plans, speech, OT, PT, and vision). Home schooled children were excluded from school outcomes due to difficulty determining whether the child was home schooled due to injury-related concerns. Health care and school services were categorized as met needs, unmet needs, unrecognized needs, and no needs similar to studies by Slomine and Greenspan.10,28

Unmet needs:

Children were categorized as having unmet needs, if their caregiver stated that the child did not receive a needed medical visit, therapy or school service since their injury. Caregivers classified the reason the child did not receive the service into choices patterned after the National Health Interview Study29: doctor did not recommend; school did not recommend or provide; cost/insurance limitation; time/access limitation; problem got better without visit; other.

Met needs:

Children were categorized as having met needs if their caregiver reported no unmet needs and their child received health care related to the injury or school services. Caregivers specified health care providers visited and school services received. Caregivers were provided a list of potential providers and school services and were allowed free text to describe services.

Unrecognized needs:

Unrecognized needs were defined as scores ≤1.5 SD below the normative mean on the CHQ and ≥1.5 SD on the SDQ or BRIEF/P with no provider visits and no caregiver report of unmet needs. Unrecognized school needs were defined as a CBCL Academic Competence score ≤1.5 SD below the normative mean with no school supports or caregiver report of unmet needs.

No needs:

Children with no health care visits or school services, no unmet need, and normal function on all measures were categorized as “no need”.

Analysis

Children with a completed pre-injury survey and at least one follow-up time point were included in the analyses. The primary outcome was unmet or unrecognized health care needs analyzed separately at 3 and 12 months using a modified Poisson regression framework.30 Variables evaluated in relationship to outcome included site (Texas v Utah), age at injury (4–5, 6–11, 12–15 years), injury severity, receipt of inpatient rehabilitation, pre-existing psychological diagnosis, receiving assistance at school pre-injury, preferred language (Spanish or English), either caregiver employed, caregiver education, insurance type, income level, family function, and social capital index. Univariable associations were assessed using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the two-sample t-test for continuous variables. Candidate variables were included in the multivariable model only if univariable p<0.20 at either the three or 12-month time point.31 Caregiver education and employment were omitted from the final model due to collinearity with insurance type and income. Associations with outcomes were summarized using relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Unmet/unrecognized school needs were evaluated using a similar approach. We omitted education, insurance, and inpatient rehabilitation (univariable p>0.05 and <0.20) from the final multivariable model due to the limited number of outcomes and observed collinearity.

Results

We enrolled 322 children with mild (37%), complicated mild/moderate (41%) and severe (22%) TBI. Figure 1 Supplemental. Most families completed all assessments (n=268, 83%) while some completed the pre-injury and 12-month (n=18, 6%) or pre-injury and three-month (n=36, 11%) assessments. Pre-injury assessments were completed a median of 8 days (IQR: 3, 14) from injury. Families who completed all assessments were more likely to be Caucasian, non-Hispanic (p = 0.02) and from Utah (p = 0.01). The cohort was diverse with 62% Caucasian non-Hispanic and 24% Hispanic children. Families reported high levels of employment (94%), insurance (91%) and access to a regular doctor or clinic (96%). One quarter of families were at or below the federal poverty level. Families reported pre-injury psychological diagnoses in 23% of the cohort. Thirteen percent of the cohort were receiving educational assistance pre-injury. Hospitalized children (n= 262, 81%) were primarily discharged to home with 32 (12%) receiving inpatient rehabilitation. Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of cohort (N=322)

| Child and family variables | Injury variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment site: Texas | 136 (42%) | Injury severity | |

| Age at injury (years), mean (SD) | 10.4 (3.6) | Mild TBI | 119 (37%) |

| Child sex: Girl | 107 (33%) | Comp. mild/moderate TBI | 133 (41%) |

| Child race/ethnicity | Severe TBI | 70 (22%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 77 (24%) | Injury mechanism | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 197 (62%) | Pedestrian or bicycle | 52 (16%) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 23 (7%) | Motorized vehicle | 108 (34%) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 22 (7%) | Fall | 108 (34%) |

| Preferred language: Spanish | 32 (10%) | Struck by or against | 27 (8%) |

| Either caregiver employed | 302 (94%) | Organized sport | 17 (5%) |

| Respondent education | Other | 10 (3%) | |

| Less than high school | 40 (12%) | Admission type | |

| High school | 71 (22%) | ED/OBS only | 60 (19%) |

| Vocational / some college | 127 (39%) | Hospital but not PICU | 104 (32%) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 84 (26%) | PICU | 158 (49%) |

| Income at or below poverty level | 73 (25%) | Head and neck AIS, median (Q1, Q3) | 3 (2, 3) |

| Insurance type | Max non-head AIS, median (Q1, Q3) | 1 (0, 2) | |

| None | 30 (9%) | ISS Score, median (Q1, Q3) | 10 (5, 17) |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 110 (34%) | Hospital discharge (n=262) | |

| Commercial/Private/Military | 181 (56%) | Home | 229 (87%) |

| Regular doctor or clinic | 308 (96%) | Inpatient rehabilitation | 32 (12%) |

| Family functioning, mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.5) | Skilled nursing | 1 (0%) |

| Social capital index, mean (SD) | 3.5 (1.1) | ||

| Pre-existing psychological diagnoses | 74 (23%) | ||

| Receiving assistance at school | 41 (13%) |

Health care utilization: Most children had at least one physical health care visit related to the TBI in the first three months post-injury (76%) which dropped to 31% in the 6–12 month time period. Approximately 54% of children had a primary care visit at three months which decreased to 20% at 12-months. Children with a primary care visit frequently saw other providers at both three and 12 months (82% and 92%, respectively). Table 2. Children with severe TBI had more physical health care visits than children with less severe injury. Few children had cognitive health visits at three or 12-months (13% and 8%, respectively) or received specialist socioemotional support.

Table 2.

| Overall | Mild TBI | Complicated Mild / Moderate TBI | Severe TBI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 month (N = 307) | 12 month (N = 286) | 3 month (N = 115) | 12 month (N = 103) | 3 month (N = 126) | 12 month (N = 117) | 3 month (N = 66) | 12 month (N = 66) | |

| Providers – Physical Health | 233 (76%) | 90 (31%) | 70 (61%) | 22 (21%) | 103 (82%) | 33 (28%) | 60 (94%) | 35 (53%) |

| Emergency Department (related to injury) | 24 (8%) | 15 (5%) | 5 (4%) | 3 (3%) | 9 (7%) | 7 (6%) | 10 (16%) | 5 (8%) |

| Hospital admission | 18 (6%) | 8 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 10 (16%) | 3 (5%) |

| Pediatrician | 125 (41%) | 41 (14%) | 43 (37%) | 11 (11%) | 50 (40%) | 16 (14%) | 32 (50%) | 14 (21%) |

| Family doctor | 45 (15%) | 17 (6%) | 14 (12%) | 5 (5%) | 22 (17%) | 8 (7%) | 9 (14%) | 4 (6%) |

| Nurse practitioner | 3 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dentist | 5 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3%) |

| Neurologist | 63 (21%) | 25 (9%) | 15 (13%) | 3 (3%) | 27 (21%) | 12 (10%) | 21 (33%) | 10 (15%) |

| Surgical subspecialists | 128 (42%) | 34 (12%) | 29 (25%) | 11 (11%) | 60 (48%) | 9 (8%) | 39 (61%) | 14 (21%) |

| Rehabilitation doctor | 77 (25%) | 19 (7%) | 15 (13%) | 2 (2%) | 36 (29%) | 9 (8%) | 26 (41%) | 8 (12%) |

| Occupational therapist | 21 (7%) | 9 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 8 (6%) | 3 (3%) | 10 (16%) | 5 (8%) |

| Physical therapist | 27 (9%) | 11 (4%) | 8 (7%) | 2 (2%) | 5 (4%) | 4 (3%) | 14 (22%) | 5 (8%) |

| Speech therapist | 34 (11%) | 16 (6%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 15 (12%) | 8 (7%) | 16 (25%) | 7 (11%) |

| Other provider | 48 (16%) | 15 (5%) | 19 (17%) | 5 (5%) | 17 (13%) | 3 (3%) | 12 (19%) | 7 (11%) |

| Providers – Cognitive Health | 40 (13%) | 23 (8%) | 6 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 17 (13%) | 12 (10%) | 17 (27%) | 9 (14%) |

| Occupational therapist | 21 (7%) | 9 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 8 (6%) | 3 (3%) | 10 (16%) | 5 (8%) |

| Speech therapist | 34 (11%) | 16 (6%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 15 (12%) | 8 (7%) | 16 (25%) | 7 (11%) |

| Neuropsychologist | 9 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (3%) | 5 (8%) | 5 (8%) |

| Providers – Socioemotional Health | 166 (54%) | 64 (22%) | 54 (47%) | 17 (17%) | 71 (56%) | 25 (21%) | 41 (64%) | 22 (33%) |

| Pediatrician | 125 (41%) | 41 (14%) | 43 (37%) | 11 (11%) | 50 (40%) | 16 (14%) | 32 (50%) | 14 (21%) |

| Family doctor | 45 (15%) | 17 (6%) | 14 (12%) | 5 (5%) | 22 (17%) | 8 (7%) | 9 (14%) | 4 (6%) |

| Psychiatrist | 12 (4%) | 12 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 8 (6%) | 6 (5%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (5%) |

| Counselor or psychologist | 6 (2%) | 12 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 5 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (6%) |

| Neuropsychologist | 9 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (3%) | 5 (8%) | 5 (8%) |

| Social worker | 0 (0%) | 5 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Outpatient Health Care Visitsa | ||||||||

| Any visit | 229 (75%) | 84 (29%) | 69 (60%) | 19 (18%) | 102 (81%) | 32 (27%) | 58 (91%) | 33 (50%) |

| Number of visits: median (IQR) | 2 (1, 5) | 0 (0, 2) |

2 (0, 4) | 0 (0, 0) | 2 (1, 5) | 0 (0, 2) | 4 (2, >10) | 1 (0, 4) |

| N=245 | N=252 | N=89 | N=86 | N=101 | N=102 | N=55 | N=64 | |

| School Services | 42 (17%) | 44 (17%) | 16 (18%) | 13 (15%) | 12 (12%) | 13 (13%) | 14 (25%) | 18 (28%) |

| Tutoring in 1 area | 6 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 5 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

|

Tutoring in 2+ areas, 504 accommodations, or homebound |

19 (8%) | 14 (6%) | 4 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 6 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 9 (16%) | 5 (8%) |

|

Special education (IEP) or speech,

vision, resource (direct service) |

17 (7%) | 27 (11%) | 7 (8%) | 7 (8%) | 5 (5%) | 8 (8%) | 5 (9%) | 12 (19%) |

Caregiver indicated at least one health care visit was related to the injury, includes physical, cognitive and socioemotional

3 month time point reflects injury to 3 months; 12 month time point reflects 6 to 12 months

IEP = individual education plan

School service utilization: Of the 281 children ≥6 years, 17% reported school service use at each timepoint. Table 2. Children with severe TBI had the most reported school service use at three (25%) and 12 (28%) months and received more intensive services; however, children with mild and complicated mild/moderate TBI also used school services. Nine children at three months and five at 12 months were excluded from school outcomes due to home schooling.

Unmet or unrecognized needs: Unmet or unrecognized health care and/or school need together occurred in 82 (28%) children at three months and 66 (24%) children at 12 months. Unmet or unrecognized needs differed by injury severity. Children with mild TBI had a higher percentage of unrecognized health care needs at three months than children with severe injury. Children with severe TBI had a low percentage of unrecognized needs at three and 12 months, but considerable unmet needs for both health care and school services. Table 3.

Table 3.

Level of health care and school need at 3 and 12 months by injury severity.

| Overall | Mild TBI | Complicated Mild /Moderate TBI | Severe TBI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 month | 12 month | 3 month | 12 month | 3 month | 12 month | 3 month | 12 month | |

| Level of need – health care | N= 303 | N=282 | N = 114 | N = 101 | N = 126 | N = 115 | N = 63 | N = 66 |

| No need | 44 (15%) | 147 (52%) | 24 (21%) | 60 (59%) | 17 (13%) | 64 (56%) | 3 (5%) | 23 (35%) |

| Met need | 193 (64%) | 80 (28%) | 57 (50%) | 22 (22%) | 89 (71%) | 28 (24%) | 47 (75%) | 30 (45%) |

| Unmet need | 43 (14%) | 19 (7%) | 16 (14%) | 3 (3%) | 15 (12%) | 8 (7%) | 12 (19%) | 8 (12%) |

| Unrecognized need | 23 (8%) | 36 (13%) | 17 (15%) | 16 (16%) | 5 (4%) | 15 (13%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (8%) |

| Level of need – schoola | N=242 | N=249 | N = 88 | N = 86 | N = 100 | N = 101 | N = 54 | N = 62 |

| No need | 176 (73%) | 193 (78%) | 62 (70%) | 65 (76%) | 84 (84%) | 85 (84%) | 30 (56%) | 43 (69%) |

| Met need | 34 (14%) | 33 (13%) | 14 (16%) | 12 (14%) | 10 (10%) | 8 (8%) | 10 (19%) | 13 (21%) |

| Unmet need | 26 (11%) | 19 (8%) | 10 (11%) | 5 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 8 (8%) | 11 (20%) | 6 (10%) |

| Unrecognized need | 6 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

School needs were only applicable for children age 6 and older at the time of assessment. This outcome also excludes 9 children at 3 months and 5 children at 12 months who were home schooled.

When examining health care, three months post-injury 22% of children had an unmet (14%) or unrecognized (8%) need; 12-months post-injury, more children had unrecognized needs (13%) than unmet needs (7%). Table 3. Among those with unmet health care needs at three months (n=43), 79% had physical, 30% had cognitive, and 26% had unmet socioemotional health care needs. At 12 months, 19 children had unmet needs with increased emphasis on socioemotional (68%) and cognitive (47%) needs. Of 23 children with unrecognized health care needs at three months, types of needs included physical (74%), cognitive (41%) or socioemotional (45%). At 12-months, unrecognized needs increased (n=36) and included physical (42%), cognitive (61%) and social emotional (67%) needs.

Unmet school service needs decreased from 11% to 8% between the three and 12-month time period. Table 3. Types of unmet school needs at three and 12 months included classroom accommodations (77%, 53%), tutoring (35%, 74%) and special education (23%, 32%). Few children had unrecognized school needs across injury severity categories; however, unmet needs occurred in all severity categories.

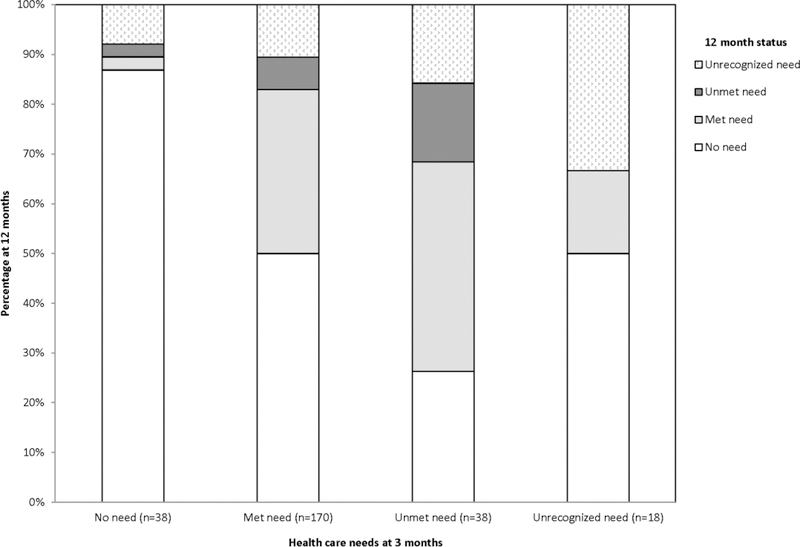

Figure 1 displays the change in health care needs from three to 12-months among children with both 3 and 12-month outcomes. For example, among 38 children with an unmet need at three months, 42% had a met need and 32% had unmet or unrecognized needs at 12-months. Of children with met needs at three months, half had no needs at 12-months, but 17% had unrecognized or unmet needs.

Figure 1.

Change in healthcare from 3 to 12 months.

Predictors of unmet and unrecognized need

Healthcare:

Supplemental Tables 1a and 1b display univariable associations with health care needs categorized by unmet and unrecognized. In multivariable modeling, factors associated with unmet or unrecognized health care needs changed between the three and 12-month time points. Table 4. Three months post-injury, children aged 6–11 years, those with pre-existing psychological diagnoses, and families with low social capital were most likely to have unmet or unrecognized health care needs. Children with complicated mild TBI had a lower risk of unmet or unrecognized health care needs compared to children with mild or severe TBI. At 12 months, child inpatient rehabilitation, pre-existing psychological diagnoses, lower family income, and problematic family function were associated with unmet or unrecognized health care needs. For inpatient rehabilitation, this association was largely driven by increased unmet needs identified by caregivers (Supplemental Table 1b). The most frequent reasons caregivers reported for unmet health care needs at three months post-injury included cost/insurance limitations (28%), time/access limitations (28%) and doctor not recommending services (23%). At 12 months, cost/insurance limitations (26%) and time/access limitations (42%) remained important reasons for unmet needs.

Table 4.

Multivariable model results for unmet/unrecognized health care need at 3 and 12 months

| 3 month (N=269) | 12 month (N=252) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Risk (95% CI) | p | Relative Risk (95% CI) | P | |

| Age at injury | 0.02 | 0.09 | ||

| 4–5 years | 0.72 (0.29, 1.81) | 1.97 (0.99, 3.91) | ||

| 6–11 years | 1.75 (1.09, 2.82) | 1.61 (0.95, 2.72) | ||

| 12–15 years | Reference | Reference | ||

| Insurance type | 0.04 | 0.71 | ||

| None | 1.72 (0.89, 3.33) | 0.88 (0.35, 2.22) | ||

| Medicaid/CHIP | 0.74 (0.41, 1.31) | 0.75 (0.37, 1.51) | ||

| Commercial/Private/Military | Reference | Reference | ||

| Income level | 0.85 (0.72, 1.00) | 0.055 | 0.76 (0.61, 0.95) | 0.01 |

| Family function | 1.04 (0.66, 1.62) | 0.87 | 2.36 (1.44, 3.88) | <0.001 |

| Social capital index | 0.73 (0.59, 0.90) | 0.003 | 1.12 (0.89, 1.40) | 0.34 |

| Pre-existing psychological diagnoses | 1.79 (1.03, 3.12) | 0.04 | 1.83 (1.04, 3.21) | 0.04 |

| Receiving assistance at school | 0.57 (0.26, 1.26) | 0.16 | 1.67 (0.94, 2.97) | 0.08 |

| TBI severity | 0.02 | 0.65 | ||

| Mild | Reference | Reference | ||

| Complicated mild/moderate | 0.47 (0.28, 0.81) | 1.15 (0.67, 1.97) | ||

| Severe | 1.01 (0.55, 1.86) | 0.86 (0.45, 1.64) | ||

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 0.52 (0.20, 1.35) | 0.18 | 2.04 (1.05, 3.96) | 0.04 |

School:

Unmet/unrecognized school needs were associated with injury severity at 3 months with the severe group having the highest risk. At 12 months, problematic family function and lower social capital were associated with higher risk of unmet/unrecognized school needs. Table 5. The most commonly reported reason for unmet school needs was that the school did not recommend or provide the service at three (24%) and 12 months (56%).

Table 5.

Multivariable model results for unmet/unrecognized school need at 3 and 12 months

| 3 month (N=220) | 12 month (N=226) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Risk (95% CI) | p | Relative Risk (95% CI) | p | |

| Income level | 0.97 (0.80, 1.18) | 0.76 | 0.86 (0.66, 1.11) | 0.25 |

| Family function | 1.63 (0.86, 3.08) | 0.14 | 1.99 (0.96, 4.15) | 0.07 |

| Social capital index | 1.19 (0.82, 1.72) | 0.36 | 0.68 (0.46, 1.01) | 0.05 |

| TBI severity | 0.01 | >0.99 | ||

| Mild | Reference | Reference | ||

| Complicated mild/moderate | 0.41 (0.15, 1.12) | 1.04 (0.40, 2.66) | ||

| Severe | 1.79 (0.87, 3.70) | 0.99 (0.35, 2.82) | ||

Discussion

In this longitudinal study of children’s health care and school needs after TBI, we found that children’s unmet and unrecognized needs are similar to those reported a decade ago. Nearly 30% of children continue to have difficulty accessing health care or school services. Needed health care services include access to specialist physicians and cognitive and socioemotional providers. School service needs included classroom accommodations, tutoring and special education. Children’s health care and school needs are dynamic with needs changing from primarily physical early after injury to cognitive and socioemotional one-year post-injury. Children’s health care and school needs were related to injury characteristics such as age at injury and injury severity, to family characteristics including family functioning, financial and social resources, and to children’s pre-existing psychological diagnoses.

Physical, cognitive, and socioemotional health needs were reported by 20–22% of parents across the year follow-up. Of the children with unmet needs, physical needs persisted while cognitive and socioemotional needs increased over time. Unmet needs for cognitive and socioemotional health care are not surprising. Children with TBI are known to have persistent difficulties with behavior and emotion,32,33 that may be recognized early or over time; thus, the need for socio-emotional support should be anticipated and screened for at intervals.34 Pediatricians report difficulties in referring children to both SLP and neuropsychology.5 Families who receive Medicaid insurance find access to these providers particularly challenging due to long waits or unavailability, as many of our families reported.16,35

Addressing children’s health care needs is complicated further by the low rate of primary care follow-up. Only 20% of children had a primary care visit between six and 12 months after injury even though over 90% of children had a regular source of care. This lack of follow-up care for concussion and more severe injury has been noted previously among insured populations,36,37 and may be a reason that unrecognized health care needs increased in our cohort. Primary care physicians routinely screen children for developmental, psychological and school problems which would potentially reveal children’s deficits, and are well positioned to help families obtain school and community services.

Families with unmet school needs cited that schools did not recommend services. While some school systems have specialist TBI teams that provide assessment and recommendations for children with TBI,7 others rely on usual school assessments to recommend services. Although IDEA requires that children be evaluated in areas of suspected disabilities, usual school assessments are geared toward identification of developmental learning disorders such as dyslexia. Such evaluations are inadequate for children with TBI who may test in the typical range for IQ and achievement, but have learning difficulties related to executive functions including the ability to shift attention, manipulate information in working memory, and impulsivity.38–40 Increasing academic challenges may develop years after injury, especially in children with complicated-mild/moderate TBI and in children injured at a younger age.41,42

The risk of unmet needs was related to severity of injury. Severe TBI was associated with greater health and school needs when assessed 3 months, but not 12 months after TBI. Unlike prior studies that found mild TBI severity predicted unmet/unrecognized need a year and two years after injury10,16 we found that children with complicated mild/moderate TBI had a lower risk of unmet/unrecognized needs early after injury after adjustment for pre-existing psychological diagnoses. This may be in part due to our cohort definition which included children with mild TBI who were not hospitalized unlike previous studies whose mild groups were more severely injured.10,16 In contrast to results from a recent study by Fuentes, that complicated mild TBI severity predicted health care needs, we did not find increased health care needs at 12-months for this group.16 In our cohort at 12-months, post-injury health care needs were greatest in the group who received inpatient rehabilitation after injury. Inpatient rehabilitation transition programs help children access care and transition to school from the hospital, although these types of care are variable.43 Differences in results may reflect cohort differences: our cohort had families with lower financial and educational resources and a higher proportion of Hispanic and Spanish speaking families which may have decreased families’ ability to access resources after the initial transition of care.44 Prior studies have reported an association of receipt of school services in children with severe TBI who received transition services; however, receipt of services was measured at three months.7 Inpatient rehabilitation programs may not follow children as their care needs change; thus, this group of children may not retain the advantage conferred by transition services. Children with severe injuries frequently make rapid gains initially after injury, but have new or persisting difficulties with executive function, anxiety and depression later after injury.1,45 This coincides with the unmet and unrecognized needs for both cognitive and socioemotional services in our cohort and represents a gap in care.

Children of families with low financial resources, low social capital or family dysfunction were at higher risk of unmet or unrecognized health care and school needs. Families with multiple challenges may not have the time or internal resources to advocate for their children or travel to appointments. Because injuries occur disproportionately to lower income children,46 this represents a substantial proportion of families. Interventions designed to improve care access and reduce disparities for children with TBI may need structured family supports.

Limitations

Study limitations include use of parent recall for children’s health care visits and school accommodations which may underestimate their use. Unmet needs by were defined by parent report which may differ from health care providers’ or schools’ determination of needs. Most parents recognize school support through formal programs such as IDEA as this requires a parent conference; however, parents may be unaware of limited accommodations such as extra time for exams or note taking leading to under-reporting. Parents may not have understood names of therapies or doctors although parents took advantage of the free text option to specify needs and services which we categorized and included. Strengths include the large diverse cohort, inclusion of all severity of TBI, longitudinal follow-up and domain-specific outcome measures.

Conclusions

Despite substantial growth in knowledge over the past decade regarding consequences of TBI, this current cohort reflects little progress in reducing the number of children with TBI who have unmet/unrecognized health care needs. Children’s unmet and unrecognized needs after TBI transform over time; initial needs are largely physical while socioemotional and cognitive needs emerge later. This change in needs should be anticipated when designing health care and school programs aimed at children with TBI. School and health care interventions for children with TBI should include supports for families who struggle with cost, insurance coverage and time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This study was supported by The Centers for Disease Control under Cooperative Agreement U01/CE002188. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Keenan was supported also by the National Institute of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development K24HD072984.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts of interest relevant to this article exist for any author.

References

- 1.Keenan HT, Clark AE, Holubkov R, Cox CS, Ewing-Cobbs L. Psychosocial and Executive Function Recovery Trajectories One Year after Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: The Influence of Age and Injury Severity. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(2):286–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rivara FP, Koepsell TD, Wang J, et al. Disability 3, 12, and 24 months after traumatic brain injury among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1129–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rice SA, Blackman JA, Braun S, Linn RT, Granger CV, Wagner DP. Rehabilitation of children with traumatic brain injury: descriptive analysis of a nationwide sample using the WeeFIM. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(4):834–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zonfrillo MR, Durbin DR, Winston FK, Zhao H, Stineman MG. Physical disability after injury-related inpatient rehabilitation in children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keenan HT, Bratton SL, Dixon RR. Pediatricians’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors to Screening Children After Complicated Mild TBI: A Survey. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017;32(6):385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Law 108– 446: IDEA 2004.

- 7.Glang A, Todis B, Thomas CW, Hood D, Bedell G, Cockrell J. Return to school following childhood TBI: who gets services? NeuroRehabilitation. 2008;23(6):477–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haarbauer-Krupa J, Lundine JP, DePompei R, King TZ. Rehabilitation and school services following traumatic brain injury in young children. NeuroRehabilitation. 2018;42(3):259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haarbauer-Krupa J, Ciccia A, Dodd J, et al. Service Delivery in the Healthcare and Educational Systems for Children Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Gaps in Care. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017;32(6):367–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slomine BS, McCarthy ML, Ding R, et al. Health care utilization and needs after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):e663–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halstead ME, Walter KD, Council on Sports M, Fitness. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical report--sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):597–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation. Guidelines ofr Diagnosing and Managing Pediatric Concussion. 2014. http://onf.org/system/attachments/266/original/GUIDELINES_for_Diagnosing_and_Managing_Pediatric_Concussion_Recommendations_for_HCPs__v1.1.pdf,. Accessed 4 June 2018.

- 13.Davis GA, Anderson V, Babl FE, et al. What is the difference in concussion management in children as compared with adults? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(12):949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lumba-Brown A, Yeates KO, Gioia G, et al. Report form the Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Guideline Workgroup. 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/pdfs/bsc/systematicreviewcompilation_august_2016.pdf.

- 15. https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/about/index.html.

- 16.Fuentes MM, Wang J, Haarbauer-Krupa J, et al. Unmet Rehabilitation Needs After Hospitalization for Traumatic Brain Injury. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2(7872):81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reilly PL, Simpson DA, Sprod R, Thomas L. Assessing the conscious level in infants and young children: a paediatric version of the Glasgow Coma Scale. Childs Nerv Syst. 1988;4(1):30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin HS, Hanten G, Roberson G, et al. Prediction of cognitive sequelae based on abnormal computed tomography findings in children following mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1(6):461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller IW, Bishop DS, Epstein NB, Kietner GI. The McMaster family assessment device: Reliability and validity. J Marital Fam Ther. 1985;11:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Runyan DK, Hunter WM, Socolar RR, et al. Children who prosper in unfavorable environments: the relationship to social capital. Pediatrics. 1998;101(1 Pt 1):12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE. Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ): A user’s Manual. Boston, MA: HealthAct; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gioia GA, Isquith PK. Ecological assessment of executive function in traumatic brain injury. Dev Neuropsychol. 2004;25(1–2):135–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gioa GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Odessa, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman R The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM. The Child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21(8):265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams J, Klinepeter K, Palmes G, Pulley A, Foy JM. Diagnosis and treatment of behavioral health disorders in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):601–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenspan AI, MacKenzie EJ. Use and need for post-acute services following paediatric head injury. Brain Inj. 2000;14(5):417–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm.

- 30.Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vittinghoff EGD, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE. Regression Methods in Biostatistics. Second ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stancin T, Drotar D, Taylor HG, Yeates KO, Wade SL, Minich NM. Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents after traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2002;109(2):E34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Liu J. The effect of pediatric traumatic brain injury on behavioral outcomes: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(1):37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson V, Beauchamp MH, Yeates KO, et al. Social Competence at Two Years after Childhood Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(14):2261–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jimenez N, Symons RG, Wang J, et al. Outpatient Rehabilitation for Medicaid-Insured Children Hospitalized With Traumatic Brain Injury. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fridman L, Scolnik M, Macpherson A, et al. Annual Trends in Follow-Up Visits for Pediatric Concussion in Emergency Departments and Physicians’ Offices. J Pediatr. 2018;192:184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keenan HT, Murphy NA, Staheli R, Savitz LA. Healthcare utilization in the first year after pediatric traumatic brain injury in an insured population. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2013;28(6):426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnett AB, Peterson RL, Kirkwood MW, et al. Behavioral and cognitive predictors of educational outcomes in pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2013;19(8):881–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ewing-Cobbs L, Barnes M, Fletcher JM, Levin HS, Swank PR, Song J. Modeling of longitudinal academic achievement scores after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Dev Neuropsychol. 2004;25(1–2):107–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hooper SR, Walker NW, Howard C. Training school psychologists in traumatic brain injury. The North Carolina model. N C Med J. 2001;62(6):350–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prasad MR, Swank PR, Ewing-Cobbs L. Long-term school outcomes of children and adolescents with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017;32(1):E24–E32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kingery KM, Narad ME, Taylor HG, Yeates KO, Stancin T, Wade SL. Do Children Who Sustain Traumatic Brain Injury in Early Childhood Need and Receive Academic Services 7 Years After Injury? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2017;38(9):728–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ennis SK, Rivara FP, Mangione-Smith R, Konodi MA, Mackenzie EJ, Jaffe KM. Variations in the quality of inpatient rehabilitation care to facilitate school re-entry and cognitive and communication function for children with TBI. Brain Inj. 2013;27(2):179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore M, Jimenez N, Rowhani-Rahbar A, et al. Availability of Outpatient Rehabilitation Services for Children After Traumatic Brain Injury: Differences by Language and Insurance Status. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;95(3):204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Max JE, Lopez A, Wilde EA, et al. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents in the second six months after traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2015;8(4):345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Birken CS, Macarthur C. Socioeconomic status and injury risk in children. Paediatr Child Health. 2004;9(5):323–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.