Abstract

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Tumorigenesis involves a multistep process resulting from the interactions of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. Genome-wide association studies and sequencing studies have identified many epigenetic alterations associated with the development of lung cancer. Epigenetic mechanisms, mainly including DNA methylation, histone modification, and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), are heritable and reversible modifications that are involved in some important biological processes and affect cancer hallmarks. We summarize the major epigenetic modifications in lung cancer, focusing on DNA methylation and ncRNAs, their roles in tumorigenesis, and their effects on key signaling pathways. In addition, we describe the clinical application of epigenetic biomarkers in the early diagnosis, prognosis prediction, and oncotherapy of lung cancer. Understanding the epigenetic regulation mechanism of lung cancer can provide a new explanation for tumorigenesis and a new target for the precise treatment of lung cancer.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem worldwide and is the second leading cause of death in the United States. Lung cancer is the most frequent cause of cancer death worldwide, with an estimate of more than 1.5 million deaths each year [1]. The majority of patients present with locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer. The 5-year survival rate of lung cancer patients varies from 4–17% depending on the disease stage [2]. The most common subtype of lung cancer is non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; 85%). NSCLC can be classified into lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), which is the most prevalent form (40%), followed by lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) (25%) and large cell carcinoma, which represents only 10% of the cases [3].

Surgery is the recommended treatment for patients with stage I-II NSCLC [4]. For patients with unresectable locally advanced NSCLC, the standard therapy is the combination therapy with chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy. In recent years, with the development of high-throughput sequencing technology, molecular targeted therapy has been widely used in patients with advanced lung cancer. Hirsch et al. showed that up to 69% of patients with advanced NSCLC could have a potentially actionable molecular target [2]. Well-known drug targets include EGFR, ALK, KRAS, c-MET, BRAF, and so on. [5]. These targeted drugs specifically block the activated kinase of the corresponding signaling pathway. Molecular targeted therapy can significantly improve patient progression-free survival compared with standard chemotherapy [6]. Molecular targeted therapies have advanced most for younger patients with LUAD, who are mostly neversmokers. Recently, EGFR-TKI has emerged as an alternative treatment option for advanced NSCLC [7–9]. These findings suggest that erlotinib monotherapy is an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for elderly Asian patients with advanced NSCLC [7]. Moreover, in patients suffering from advanced NSCLC, bevacizumab improved the overall survival when paclitaxel-carboplatin was added [10]. Over the past few decades, the treatment of lung cancer has made great progress. However, there are still many challenges, including relapse after surgery, chemotherapy resistance, resistance to targeted therapy, and so on.

The progression of cancer is a result of the accumulation of a combination of permanent genetic alterations, including point mutations, deletions, translocations, and/or amplifications, as well as dynamic epigenetic alterations, which are influenced by environmental factors [11]. The most commonly mutated genes in LUAD include KRAS and EGFR and the tumor suppressor genes TP53, KEAP1, STK11, and NF1. Commonly mutated genes in LUSC include the tumor suppressors such as TP53, which is present in more than 90% of tumors, and CDKN2A [12]. TP53 mutations are more commonly observed with advancing stage, suggesting a role during tumor progression [13]. In contrast, the frequency of KRAS mutations in LUAD seems constant across tumor grades, suggesting a role in tumor initiation or early tumorigenesis. Mutations in these genes may affect gene expression, thereby promoting the development of lung cancer. In contrast to the somatic mutations found in lung cancer, a large number of genes are silenced or uncontrolled during lung carcinogenesis through epigenetic modifications. Epigenetic mechanisms are heritable and reversible, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin organization, and noncoding RNAs. A large number of studies have shown that epigenetics plays an important role in the development of lung cancer.

In this review, we summarize the major epigenetic modifications in lung cancer, focusing on DNA methylation and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) and their roles in tumorigenesis. In addition, we describe the clinical application of epigenetic biomarkers in the early diagnosis, prognosis prediction, and oncotherapy of lung cancer.

2. Epigenetic Alterations in Lung Cancer

2.1. Epigenetics

Epigenetic alterations have become one of the cancer hallmarks, replacing the concept of malignant pathologies as solely genetic-based conditions. Among the main mechanisms of epigenetic regulation, DNA methylation is by far the most studied and is responsible for gene silencing and chromatin structure. DNA methylation is a biological process in which a methyl group is covalently added to a cytosine, yielding 5-methylcytosine (5mC). The methylation process is carried out by a set of enzymes called DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [14]. There are five known types of DNMTs, among which DNMT1 retains the hemimethylated DNA generated during DNA replication and is required for copying the DNA methylation pattern from the template to the daughter DNA strand. In contrast, DNMT3A and DNMT3B are de novo methyltransferases that target unmethylated DNA [15]. Histone proteins are susceptible to different modifications, including ubiquitylation, sumoylation, methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation. In contrast to DNA methylation, histone covalent modifications not only silence the expression of specific genes but also promote transcription. More recently, beyond the classical epigenetic mechanisms, an increasingly recognized role as epigenetic modifiers has been given to ncRNAs, especially to microRNAs and lncRNAs [16]. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression occurs at different levels, protein levels (histone modification), DNA levels (DNA methylation), and RNA levels (ncRNAs). All of these mechanisms regulate gene expression without altering the primary DNA sequence; therefore, the resulting modifications are called epigenetic alterations.

2.2. Epigenetic Landscape in Lung Cancer

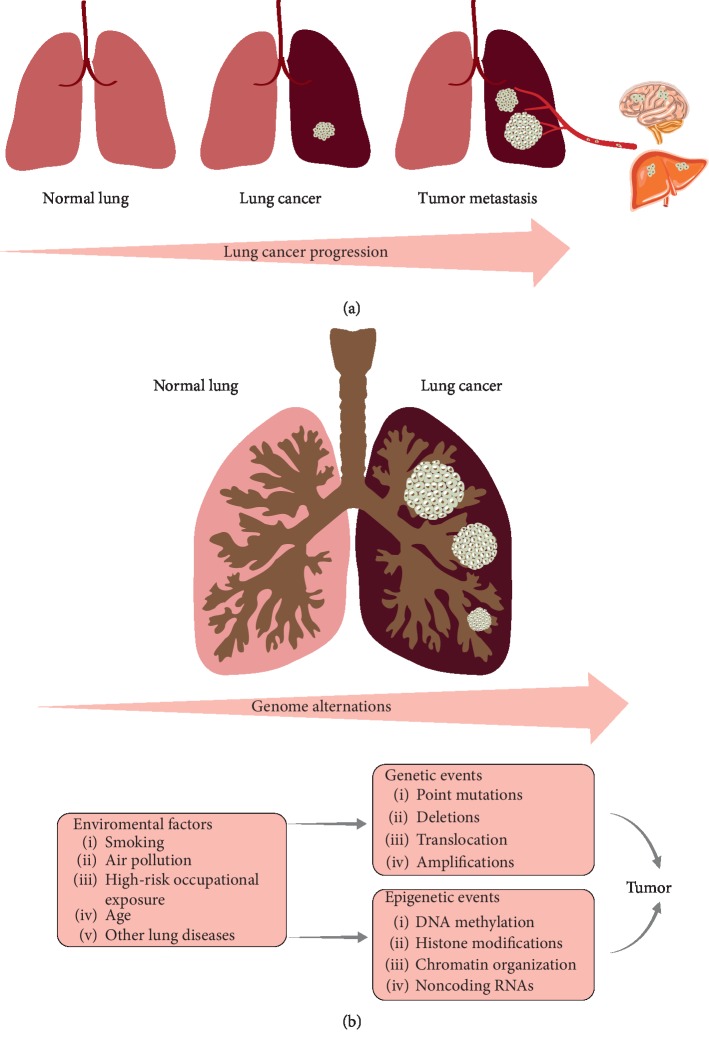

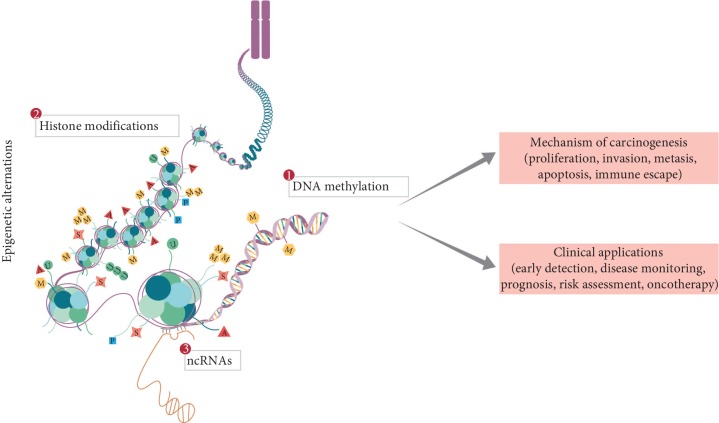

Tumorigenesis involves a multistep process resulting from the interactions of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors (Figure 1). Recent advances in epigenetics provide a better understanding of the underlying mechanism of carcinogenesis. DNA hypermethylation is a hallmark in lung cancer and an early event in carcinogenesis. ncRNAs play an important role in a number of biological processes, including RNA-RNA interactions and epigenetic and posttranscriptional regulation [17]. Changes in these epigenetic factors result in the dysregulation of key oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [18,19]. Many of the epigenetic events in lung cancer affect cancer hallmarks, such as proliferation [20–23], invasion [24–26], metastasis [27–33], apoptosis [34–37], and cell cycle regulation. In addition to cancer hallmarks, several important signaling pathways are affected by epigenetic deregulation in lung cancer, such as the ERK family, the NF-kB signaling pathway, and the Hedgehog signaling pathway [18]. Simultaneously, epigenetic events provide insight into the discovery of putative cancer biomarkers for early detection, disease monitoring, prognosis, risk assessment, and oncotherapy (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Genomic changes associated with the progression of lung cancer. Tumorigenesis involves a multistep process resulting from the interactions of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. The progression from normal lung tissue to malignant phenotype is accompanied by alterations in these three factors. (a) Morphological changes. (b) Genomic changes.

Figure 2.

Current landscapes of epigenetics mechanism and application in lung cancer. Epigenetic mechanisms are heritable and reversible, mainly including DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin organization, and noncoding RNAs. Many of the epigenetic events in lung cancer affect cancer hallmarks, such as tumor cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation. Simultaneously, epigenetic events provide insight into the discovery of putative cancer biomarkers for early detection, disease monitoring, prognosis, risk assessment, and oncotherapy.

2.3. DNA Methylation in Lung Cancer

DNA methylation is an epigenetic event whose pattern is altered frequently in a wide variety of human cancers, including genome-wide hypomethylation and promoter-specific hypermethylation [38]. We summarized the genes for aberrant methylation in lung cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Abnormally methylated genes in lung cancer.

| Gene | Mechanism | Epigenetic modification | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| RASSF1A | DNA repair; cell cycle | Hypermethylation | [40,41] |

| MGMT | DNA repair | Hypermethylation | [45] |

| CDKN2A/p16 | Cell cycle | Hypermethylation | [51,52] |

| DAPK | Apoptosis; autophagy | Hypermethylation | [34–36,59,60] |

| P14 | Proliferation; apoptosis | Hypermethylation | [20] |

| OTUD4 | Cell cycle; apoptosis; DNA repair | Hypermethylation | [81,96,97] |

| CDH1/E-cadherin | EMT | Hypermethylation | [98,99] |

| RARβ | Metastasis | Hypermethylation | [27,100–102] |

| RUNX3 | TGF-β/Wnt signaling pathway | Hypermethylation | [103–106] |

| APC | Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | Hypermethylation | [107–109] |

RASSF1A (Ras association domain family 1A) is a putative tumor suppressor gene and effector molecule that mediates the apoptotic effects of Ras by binding to Ras in a GTP-dependent manner [39]. In addition to apoptosis, RASSF1A has been implicated in the DNA damage response [40] and the induction of cell cycle arrest through the accumulation of cyclin D1 [41]. Previous studies have shown that RASSF1A hypermethylation has early diagnostic and prognostic value in lung cancer [42–44].

MGMT (O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase) is one of the most important DNA repair proteins, and its silencing is apparently involved in carcinogenesis [45]. Compared with primary lung cancer, MGMT expression was enhanced in brain metastases, and MGMT expression in brain metastasis was significantly associated with better survival [46]. MGMT promoter hypermethylation is a common event in lung cancer patients. This epigenetic alteration is associated with inferior survival, suggesting that MGMT promoter hypermethylation might be an important biomarker for biologically aggressive diseases in NSCLC [47]. Pulling et al. [48] demonstrated that the incidence of MGMT methylation was significantly higher in neversmokers than in smokers and detected a higher frequency of mutations within the KRAS gene in neversmokers than previously reported.

CDKN2A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A) has been given different names (pl6INK4, p16INK4A, CDK4I, MTS1, and p16) by different investigators but was finally designated as CDKN2A by the Human Genome Organisation Gene Nomenclature Committee [49]. CDKN2A is one of the most widely studied proteins in the past few decades because of its critical roles in cell cycle progression, cellular senescence, and the development of human cancers [50]. CDKN2A is a tumor suppressor that functions as an inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK6, the D-type cyclin-dependent kinases that initiate the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor protein, and induces cell cycle arrest [51,52]. CDKN2A is frequently inactivated by homozygous deletion or promoter hypermethylation and rarely by point mutation in primary NSCLC [53,54]. Previous studies have shown that the CDKN2A promoter region was methylated in lung cancer at frequencies between 20% and 70% [55]. Xiao et al. found that the detection of CDKN2A promoter methylation in exhaled breath condensate (EBC) was feasible and would be a useful biomarker for the diagnosis of NSCLC. The detection of gene molecules in EBC is noninvasive, specific, convenient, and repeatable [56].

DAPK (death-associated protein kinase) is a proapoptotic serine⁄threonine protein kinase that is dysregulated in a wide variety of cancers [57]. The mechanism by which this regulation occurs has largely been attributed to promoter hypermethylation, which results in gene silencing. DAPK promoter hypermethylation is correlated with the risk of NSCLC and is a potential biomarker for the prediction of poor prognosis in patients with NSCLC [58]. Previous investigations have indicated that DAPK plays an important role in apoptosis [34,59,60], autophagy [35,36], tumor suppression, and metastasis suppression [59,61]. Chen et al. [62] provided evidence derived from cell, animal, and clinical studies supporting DAPK as a metastatic suppressor; these authors further discussed the underlying mechanisms by which DAPK functions to suppress tumor metastasis.

These genes may be important in the biological development of lung cancer and are frequently methylated in lung cancer.

2.4. ncRNAs in Lung Cancer

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), including long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), short microRNAs (miRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), control various levels of gene expression in disease, such as epigenetic memory, transcription, RNA splicing, editing, translation, and possibly tumorigenesis [63,64]. Recent evidence has suggested that a number of ncRNAs play crucial roles in the development of lung cancer. These molecules were identified as oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes involved in regulating tumorigenesis and tumor progression [65]. The main dysregulated lncRNAs and miRNAs in lung cancer are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2.

LncRNAs deregulated in lung cancer.

| LncRNA | Mechanism | Clinical utility | Expression | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOTAIR | Invasion; metastasis | Prognostic biomarker; therapeutic target | Upregulated | [28–30,67] |

| H19 | Proliferation; migration; invasion | Prognostic biomarker | Upregulated | [110–112] |

| MALAT1 | Migration; invasion; chemoresistance | Predictive biomarker | Upregulated | [24,113,114] |

| ANRIL | Proliferation; apoptosis; cell cycle | Prognostic biomarker | Upregulated | [115,116] |

| LINC00668 | Proliferation; migration; invasion; apoptosis. | Prognostic biomarker | Upregulated | [25,117] |

| LINC01436 | Metastasis | Prognostic biomarker | Upregulated | [31] |

| SUMO1P3 | Metastasis | Therapeutic target | Upregulated | [32] |

| MNX1-AS1 | Proliferation; migration; apoptosis | Prognostic biomarker | Upregulated | [21] |

| RHPN1-AS1 | Gefitinib resistance | Prognostic biomarker; therapeutic target | Downregulated | [118] |

| MIR31HG | Cell cycle; proliferation | Prognostic biomarker | Upregulated | [119] |

Table 3.

miRNAs deregulated in lung cancer.

| miRNA | Mechanism | Clinical utility | Expression level | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | Apoptosis | Prognostic biomarker; therapeutic target | Upregulated | [70,120] |

| miR-495 | Proliferation; migration; invasion; EMT; drug resistance | Therapeutic target | Downregulated | [22] |

| miR-661 | Invasion; metastasis | Therapeutic target | Upregulated | [72,121] |

| miR-3607-3p | Cell cycle; metastasis | Prognostic biomarker; therapeutic target | Downregulated | [122] |

| miR-181b | Migration; invasion | Therapeutic target | Downregulated | [26] |

| miR -19 | Proliferation; migration | Therapeutic target | Upregulated | [23] |

| miR-182 | Cell cycle; apoptosis | Diagnostic/prognostic biomarker | Upregulated | [123] |

| miR-505-5p | Proliferation; apoptosis | Diagnostic biomarker | Upregulated | [124] |

| miR-1290 | Metastasis | Prognostic biomarker | Upregulated | [125] |

| miR-CHA1 | Proliferation; apoptosis | Therapeutic target | Downregulated | [126] |

| miR-193a-3p, miR-210-3p, miR-5100 | Metastasis; EMT | Diagnostic biomarker | Upregulated | [33] |

| miR-374b | Apoptosis | Therapeutic target | Downregulated | [37] |

Many recent reports have identified aberrant lncRNA expression profiles associated or involved with different human malignant diseases. These lncRNAs regulate tumor-critical genes in the development of cancers. In lung cancer, the frequently reported cancer-associated lncRNAs include HOTAIR, H19, MALAT1, ANRIL, and GAS5 [66]. lncRNA HOX transcript antisense RNA (HOTAIR) represses gene expression through the recruitment of chromatin modifiers [67]. HOTAIR exhibits significantly higher expression in tumor tissue than in adjacent nontumor tissue in lung cancer. The high expression of HOTAIR is associated with metastasis and the poor prognosis of lung cancer [28,29]. Jiang et al. [30] indicated that the downregulation of HOTAIR suppressed the tumorigenesis and metastasis of NSCLC by upregulating the expression of miR-613. The HOTAIR/miR-613 axis might provide a new potential therapeutic strategy for NSCLC treatment. A newly identified lncRNA, LINC00668, was reported to be involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis in lung cancer [25]. Drug resistance is an important factor leading to the recurrence and metastasis of lung cancer. Yang et al. [68] showed that silencing HOTAIR decreased the drug resistance of NSCLC cells to crizotinib through the inhibition of autophagy by suppressing the phosphorylation of ULK1.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are the most widely studied ncRNAs in lung cancer. miRNAs regulate many biological processes, including cell cycle regulation, cellular growth, proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, metabolism, neuronal patterning, and aging [69]. Some miRNAs can act as tumor suppressor genes, while others can act as oncogenes that stimulate the growth of tumors. For instance, miR-21 is frequently overexpressed in NSCLC. miR-21 overexpression accelerates tumorigenesis by targeting SPRY1, SPRY2, BTG2, and PDCD4, which act as negative regulators of the RAS/MEK/ERK pathway, and APAF-1, FASLG, PDCD4, and RHOB, which are involved in apoptosis [70]. In contrast, miR-101 is downregulated in NSCLC, leading to the enhanced expression of its target gene MCL-1 in NSCLC, thus favoring tumor succession through the inhibition of apoptosis [71]. The current results indicate that the miR495-UBE2C-ABCG2/ERCC1 axis reverses cisplatin resistance by downregulating drug resistance genes in cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells [22]. The present results also indicate that miR-661 plays an oncogenic role in NSCLC by directly targeting RUNX3, thus indicating that miR-661 can be used to develop new therapies for patients with NSCLC [72]. An increasing number of studies have shown that miRNAs could be used not only as specific biomarkers of cancer (diagnostic biomarkers) but also as dynamic markers of tumor status before (prognostic biomarkers) and during treatment (predictive biomarkers) [73].

CircRNAs, a class of endogenous noncoding RNAs that differ from linear RNAs, are closed circRNA molecules formed by reverse splicing. CircRNAs are transcripts that lack the 5′end cap and a 3′ end poly(A) tail, forming a covalent closed loop [74]. The mechanism of circRNA mainly includes interactions with chromatin histones, binding to RNA polymerase, capturing proteins from its original mRNA, encoding exons and sponge miRNAs, capturing transcription factors in the cytoplasm, and preventing gene transcription [75,76]. With the development of high-throughput sequencing technology, an increasing number of differentially expressed circRNAs have been discovered that are involved in the development of lung cancer. These findings suggested that circRNAs may be a potential marker for the diagnosis and prognosis of lung cancer [76]. Currently, most studies on circRNAs in lung cancer are focused on their miRNA sponge activity. A growing number of studies have evaluated the role of the circRNA-miRNA-mRNA axis in lung cancer. For instance, Hsa_circ_0007385 is significantly highly expressed in NSCLC. In-depth studies have found that hsa_circ_0007385 significantly inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion of NSCLC cells by adsorbing miR-181 and significantly reduces the growth of gene knockout xenograft tumors [77]. Similarly, circMAN2B2, which promotes FOXK1 expression by sponge action on miR-1275, plays a carcinogenic role in lung cancer [78].

2.5. Epigenetic Biomarkers in Lung Cancer

2.5.1. Diagnostic Biomarkers

Early diagnosis of cancer is one of the most important factors contributing to successful and effective treatment. Unfortunately, many lung cancer patients are diagnosed in the advanced stages due to the lack of obvious early symptoms and effective early screening. In recent years, an increasing number of researchers have examined markers for the early diagnosis of lung cancer, which has promoted research progress in this field. Shi et al. [18] identified a panel of DNA methylation biomarkers (CLDN1, TP63, TBX5, TCF21, ADHFE1, and HNF1B) in LUSC on a genome-wide scale. Furthermore, these authors performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to assess the performance of biomarkers individually, suggesting that these molecules could be suitable as potential diagnostic biomarkers for LUSC. DNA methylation represents a very stable sign that can be detected in many different types of samples, including tumor tissues and cancer cells in body fluids (blood, urine, and so on) [79]. Tissue biopsy is the gold standard indicator of current pathological diagnosis. However, tissue biopsy is traumatic and inconvenient. Noninvasive “liquid biopsy” has recently received widespread attention. Zhu et al. [80] developed classifiers including four miRNAs (miR-23b, miR-221, miR-148b, and miR-423-3p) that can be showed as a signature for early detection of lung cancer, yielding a ROC curve area of 0.885. Circulating tumor markers (including circulating tumor cells, circulating tumor DNA, exosomes, and tumor-educated platelets) have fewer lesions and more types of markers that can be detected simultaneously, providing more comprehensive disease information. With the development of cell separation technology and gene sequencing technology, the value of liquid biopsy in tumor precision medicine is increasingly prominent. For example, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing has become a new focus in the field of cancer diagnosis and treatment. The main detection methods include microdroplet digital PCR, amplification blocking mutation PCR, and second-generation sequencing. Hypoxic BMSC-derived exosomal miRNAs (miR-193a-3p, miR-210-3p, and miR-5100) promote the metastasis of lung cancer cells through STAT3-induced EMT [33]. These exosomal miRNAs may be promising noninvasive biomarkers for cancer progression.

2.5.2. Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers

Conventionally, tumor clinicopathological features, such as pathological subtype, nodal invasion, and metastasis, are used to predict disease outcome. At present, with the development of high-throughput technology and the deepening of molecular targeting technology research, in addition to these traditional predictors, abnormal epigenetic molecular markers, such as DNA methylation and noncoding RNA, can also be used for prognosis prediction. Wu et al. [81] showed that OTUD4 (OTU deubiquitinase 4) is silenced by promoter methylation and that its downregulation correlates with poor prognosis in NSCLC. Li et al. [82] found that four methylation-driven genes, GCSAM, GPR75, NHLRC1, and TRIM58, could serve as prognostic indicators for LUSC. High-throughput screening and clinical validation revealed that NEK2, DLGAP5, and ECT2 are promising biomarkers for prognosis and prediction in lung cancer [83]. Guo et al. [84] identified lncRNA-HAGLR as a positive prognostic marker for LUAD patients and found that HAGLR suppressed cell growth through the epigenetic silencing of E2F1. Therefore, the HAGLR/E2F1 axis may be explored as a therapeutic strategy to inhibit carcinogenesis and progression of LUAD. Zhang et al. [85] identified five miRNAs (miR-191, miR-28-3p, miR-145, miR-328, and miR-18a) from serum miRNA profiling to predict survival in patients with advanced stage NSCLC.

2.6. Epigenetic Therapy in Lung Cancer

At present, the treatment of lung cancer mainly includes surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy. In the early stages of lung cancer, surgical resection can be chosen. Platinum-based chemotherapy for patients with advanced lung cancer is a first-line treatment. However, platinum-based chemotherapy faces two major challenges: drug resistance and drug toxicity. Therefore, exploring appropriate treatments is critical to improving the survival rate of patients with lung cancer.

Advances in epigenetics provide new perspectives for the treatment of lung cancer. Current treatments targeting chromatin regulators approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) include histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTi), and Janus kinase 2 inhibitors [11]. Among these molecules, DNMTi has been widely studied. DNA hypermethylation can be reversed by DNMTi, so the use of drugs to reverse the hypermethylation status of tumor suppressor genes has become a research hotspot for the treatment of tumors. Azacytidine and decitabine are the most extensively used DNMTi in experimental and clinical studies [86–88]. Additionally, studies have shown that the deacetylation of HDAC can lead to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes, which is closely related to the occurrence of tumors. HDACi can bind to the catalytic region of HDAC and inhibit HDAC activity, leading to hyperacetylation of histones and tumor suppression. Gene transcription, which changes the expression of genes, induces cell growth inhibition, differentiation, and apoptosis and show slow toxicity on normal cells, thus becoming a new antitumor drug with broad application prospects [89]. A variety of known HDACi, including trichostatin A, SAHA, depsipeptide, and valproic acid, and some new HDACi, such as KD5170 and R306465, have been tested in lung cancer cell lines and transplantation models. In view of the limited effect of epigenetic monotherapy on solid tumors to improve the therapeutic effect, the combination of DNMTi or HDACi with conventional chemotherapy, kinase inhibitors, or immunotherapy has been intensively explored in prospective clinical trials [90–92]. ncRNAs are also important drug targets, and their mechanism of action is to enhance tumor suppressor genes or inhibit oncogenes. Much miRNA-based therapeutics are being tested in clinical trials [93]. For example, MRX34 (miR-34a mimic) is currently being tested in a Phase I clinical trial for multiple solid tumors [94]. MesomiR-1 (miR-16 mimic) is currently being tested in a Phase I clinical trial for malignant pleural mesothelioma and advanced non-small cell lung cancer [95]. In addition to miRNA mimic, miRNA sponges have also been extensively studied. The miRNA sponge mainly includes lncRNAs and circRNAs and can be used as a tool for identifying miRNA targets and studying the molecular function. Among them, the miRNA sponge effect produced by circRNA has been widely concerned. RNA-based drugs are a hot research topic nowadays. In the application of such drugs, if the off-target effect and other problems can be fully solved, such drugs will have a promising prospect. Epigenetic therapies (DNMTi, HDACi, and RNA-based therapeutics) may yield great opportunities in the treatment of NSCLC.

3. Conclusions and Perspectives

Based on a large number of previous studies, we reviewed major epigenetic changes in lung cancer, focusing on DNA methylation and ncRNAs and their involvement in carcinogenesis. In addition, we described the clinical application of epigenetic biomarkers in the early diagnosis, prognosis prediction, and oncotherapy of lung cancer. The in-depth study of epigenetics provides a new mechanism for the occurrence and development of lung cancer and a new target for the early diagnosis and effective treatment of lung cancer. Continued research into new drugs and combination therapies will benefit more patients and improve lung cancer prognosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81172788) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (no. 2018CFB142).

Contributor Information

Yuan-Xiang Shi, Email: yuanxiangshi2011@csu.edu.cn.

Xin-Yu Song, Email: songxinyuhxk@126.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsch F. R., Scagliotti G. V., Mulshine J. L., et al. Lung cancer: current therapies and new targeted treatments. The Lancet. 2017;389(10066):299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zappa C., Mousa S. A. Non-small cell lung cancer: current treatment and future advances. Translational Lung Cancer Research. 2016;5(3):288–300. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2016.06.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vansteenkiste J., Crino L., Dooms C., et al. 2nd ESMO Consensus Conference on Lung Cancer: early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer consensus on diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2014;25(8):1462–1474. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ai X., Guo X., Wang J., et al. Targeted therapies for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9(101):37589–37607. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiddinga B. I., Pauwels P., Janssens A., van Meerbeeck J. P. O6—methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT): a drugable target in lung cancer? Lung Cancer. 2017;107:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu X.-H., Su J., Fu X.-Y., et al. Clinical effect of erlotinib as first-line treatment for Asian elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2011;67(2):475–479. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu L., Xu X.-H., Yuan C., et al. Clinical efficacy of icotinib in patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer with unknown EGFR mutation status that failed to respond to second-line chemotherapy. Annals of Translational Medicine. 2018;6(20):p. 405. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.09.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou B., Nie J., Yang W., Huang C., Huang Y., Zhao H. Effect of hydrothorax EGFR gene mutation and EGFR-TKI targeted therapy on advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Oncology Letters. 2016;11(2):1413–1417. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandler A., Gray R., Perry M. C., et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(24):2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta A., Dobersch S., Romero-Olmedo A. J., Barreto G. Epigenetics in lung cancer diagnosis and therapy. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2015;34(2):229–241. doi: 10.1007/s10555-015-9563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbst R. S., Morgensztern D., Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553(7689):446–454. doi: 10.1038/nature25183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahrendt S. A., Hu Y., Buta M., et al. p53 mutations and survival in stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a prospective study. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95(13):961–970. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.13.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goll M. G., Bestor T. H. Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2005;74(1):481–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasculli B., Barbano R., Parrella P. Epigenetics of breast cancer: biology and clinical implication in the era of precision medicine. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2018;51:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peschansky V. J., Wahlestedt C. Non-coding RNAs as direct and indirect modulators of epigenetic regulation. Epigenetics. 2014;9(1):3–12. doi: 10.4161/epi.27473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prensner J. R., Chinnaiyan A. M. The emergence of lncRNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Discovery. 2011;1(5):391–407. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-11-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi Y. X., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling reveals novel epigenetic signatures in squamous cell lung cancer. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):p. 901. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4223-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y., Qian C. Y., Li X. P., et al. Genome-scale long noncoding RNA expression pattern in squamous cell lung cancer. Scientific Reports. 2015;5(1):p. 11671. doi: 10.1038/srep11671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia B. Y., Yang R. H., Jiao W. J., Tian K. H. Investigation of the effect of P14 promoter aberrant methylation on the biological function of human lung cancer cells. Thoracic Cancer. 2019;10(6):1388–1394. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang R., Wang L., Han M. MNX1-AS1 is a novel biomarker for predicting clinical progression and poor prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2019;120(5):7222–7228. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo J., Jin D., Wu Y., et al. The miR 495-UBE2C-ABCG2/ERCC1 axis reverses cisplatin resistance by downregulating drug resistance genes in cisplatin-resistant non-small cell lung cancer cells. EBioMedicine. 2018;35:204–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 23.Peng X., Guan L., Gao B. miRNA-19 promotes non-small-cell lung cancer cell proliferation via inhibiting CBX7 expression. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2018;11:8865–8874. doi: 10.2147/ott.s181433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang Y., Xiao G., Chen Y., Deng Y. LncRNA MALAT1 promotes migration and invasion of non-small-cell lung cancer by targeting miR-206 and activating Akt/mTOR signaling. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2018;29:725–735. doi: 10.1097/cad.0000000000000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.An Y.-X., Shang Y.-J., Xu Z.-W., et al. STAT3-induced long noncoding RNA LINC00668 promotes migration and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer via the miR-193a/KLF7 axis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2019;116 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109023.109023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y., Hu X., Xia D., Zhang S. MicroRNA-181b is downregulated in non-small cell lung cancer and inhibits cell motility by directly targeting HMGB1. Oncology Letters. 2016;12(5):4181–4186. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehrotra J. Very high frequency of hypermethylated genes in breast cancer metastasis to the bone, brain, and lung. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(9):3104–3109. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X. H., Liu Z. L., Sun M., Liu J., Wang Z. X., De W. The long non-coding RNA HOTAIR indicates a poor prognosis and promotes metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):p. 464. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao W., An Y., Liang Y., Xie X. W. Role of HOTAIR long noncoding RNA in metastatic progression of lung cancer. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2014;18(13):1930–1936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang C., Yang Y., Yang Y., et al. Long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) HOTAIR affects tumorigenesis and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer by upregulating miR-613. Oncology Research Featuring Preclinical and Clinical Cancer Therapeutics. 2018;26(5):725–734. doi: 10.3727/096504017x15119467381615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan S., Xiang Y., Wang G., et al. Hypoxia-sensitive LINC01436 is regulated by E2F6 and acts as an oncogene by targeting miR-30a-3p in non-small cell lung cancer. Molecular Oncology. 2019;13(4):840–856. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y., Li Y., Han L., Zhang P., Sun S. SUMO1P3 is associated clinical progression and facilitates cell migration and invasion through regulating miR-136 in non-small cell lung cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2019;113 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108686.108686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X., Sai B., Wang F., et al. Hypoxic BMSC-derived exosomal miRNAs promote metastasis of lung cancer cells via STAT3-induced EMT. Molecular Cancer. 2019;18(1):p. 40. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0959-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raveh T., Droguett G., Horwitz M. S., DePinho R. A., Kimchi A. DAP kinase activates a p19ARF/p53-mediated apoptotic checkpoint to suppress oncogenic transformation. Nature Cell Biology. 2001;3(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/35050500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inbal B., Bialik S., Sabanay I., Shani G., Kimchi A. DAP kinase and DRP-1 mediate membrane blebbing and the formation of autophagic vesicles during programmed cell death. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;157(3):455–468. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin Y., Hupp T. R., Stevens C. Death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) and signal transduction: additional roles beyond cell death. FEBS Journal. 2010;277(1):48–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y., Yu L., Wang T. MicroRNA-374b inhibits the tumor growth and promotes apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer tissue through the p38/ERK signaling pathway by targeting JAM-2. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2018;10(9):5489–5498. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.09.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones P. A., Baylin S. B. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2002;3(6):415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vos M. D., Ellis C. A., Bell A., Birrer M. J., Clark G. J. Ras uses the novel tumor suppressor RASSF1 as an effector to mediate apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(46):35669–35672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.c000463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamilton G., Yee K. S., Scrace S., O’Neill E. ATM regulates a RASSF1A-dependent DNA damage response. Current Biology. 2009;19(23):2020–2025. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shivakumar L., Minna J., Sakamaki T., Pestell R., White M. A. The RASSF1A tumor suppressor blocks cell cycle progression and inhibits cyclin D1 accumulation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22(12):4309–4318. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.12.4309-4318.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ko E., Lee B. B., Kim Y., et al. Association of RASSF1A and p63 with poor recurrence-free survival in node-negative stage I-II non-small cell lung cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2013;19(5):1204–1212. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-12-2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim H., Kwon Y. M., Kim J. S., et al. Tumor-specific methylation in bronchial lavage for the early detection of non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(12):2363–2370. doi: 10.1200/jco.2004.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Begum S., Brait M., Dasgupta S., et al. An epigenetic marker panel for detection of lung cancer using cell-free serum DNA. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(13):4494–4503. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-10-3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soejima H., Zhao W., Mukai T. Epigenetic silencing of the MGMT gene in cancer. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2005;83(4):429–437. doi: 10.1139/o05-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu P.-F., Kuo K.-T., Kuo L.-T., et al. O6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase expression and prognostic value in brain metastases of lung cancers. Lung Cancer. 2010;68(3):484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brabender J., Usadel H., Metzger R., et al. Quantitative O(6)-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase methylation analysis in curatively resected non-small cell lung cancer: associations with clinical outcome. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;9(1):223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pulling L. C., Divine K. K., Klinge D. M., et al. Promoter hypermethylation of the O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene: more common in lung adenocarcinomas from never-smokers than smokers and associated with tumor progression. Cancer Research. 2003;63(16):4842–4848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foulkes W. D., Flanders T. Y., Pollock P. M., Hayward N. K. The CDKN2A (p16) gene and human cancer. Molecular Medicine. 1997;3(1):5–20. doi: 10.1007/bf03401664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J., Poi M. J., Tsai M.-D. Regulatory mechanisms of tumor suppressor P16INK4Aand their relevance to cancer. Biochemistry. 2011;50(25):5566–5582. doi: 10.1021/bi200642e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohtani N., Yamakoshi K., Takahashi A., Hara E. The p16INK4a-RB pathway: molecular link between cellular senescence and tumor suppression. The Journal of Medical Investigation. 2004;51(3-4):146–153. doi: 10.2152/jmi.51.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tam K. W., Zhang W., Soh J., et al. CDKN2A/p16 inactivation mechanisms and their relationship to smoke exposure and molecular features in non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2013;8(11):1378–1388. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e3182a46c0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwakawa R., Kohno T., Anami Y., et al. Association of p16 homozygous deletions with clinicopathologic characteristics and EGFR/KRAS/p53 mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2008;14(12):3746–3753. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-07-4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kraunz K. S., Nelson H. H., Lemos M., Godleski J. J., Wiencke J. K., Kelsey K. T. Homozygous deletion of p16INK4a and tobacco carcinogen exposure in nonsmall cell lung cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;118(6):1364–1369. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nuovo G. J., Plaia T. W., Belinsky S. A., Baylin S. B., Herman J. G. In situ detection of the hypermethylation-induced inactivation of the p16 gene as an early event in oncogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999;96(22):12754–12759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiao P., Chen J. R., Zhou F., et al. Methylation of P16 in exhaled breath condensate for diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;83(1):56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michie A. M., McCaig A. M., Nakagawa R., Vukovic M. Death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) and signal transduction: regulation in cancer. FEBS Journal. 2010;277(1):74–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y., Wu J., Huang G., Xu S. M. Clinicopathological significance of DAPK promoter methylation in non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Management and Research. 2018;10:6897–6904. doi: 10.2147/cmar.s174815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Inbal B., Cohen O., Polak-Charcon S., et al. DAP kinase links the control of apoptosis to metastasis. Nature. 1997;390(6656):180–184. doi: 10.1038/36599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martoriati A., Doumont G., Alcalay M., Bellefroid E., Pelicci P. G., Marine J. C. dapk1, encoding an activator of a p19ARF-p53-mediated apoptotic checkpoint, is a transcription target of p53. Oncogene. 2005;24(8):1461–1466. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim D. H., Nelson H. H., Wiencke J. K., et al. Promoter methylation of DAP-kinase: association with advanced stage in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20(14):1765–1770. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen H. Y., Lee Y. R., Chen R. H. The functions and regulations of DAPK in cancer metastasis. Apoptosis. 2014;19(2):364–370. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0923-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ling H., Fabbri M., Calin G. A. MicroRNAs and other non-coding RNAs as targets for anticancer drug development. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2013;12(11):847–865. doi: 10.1038/nrd4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yavropoulou M. P., Poulios C., Michalopoulos N., et al. A role for circular non-coding RNAs in the pathogenesis of sporadic parathyroid adenomas and the impact of gender-specific epigenetic regulation. Cells. 2018;8(1):p. 15. doi: 10.3390/cells8010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yi J. J., Li S. B., Wang C., et al. Potential applications of polyphenols on main ncRNAs regulations as novel therapeutic strategy for cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2019;113 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108703.108703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu T., Wang Y., Chen D., Liu J., Jiao W. Potential clinical application of lncRNAs in non-small cell lung cancer. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2018;11:8045–8052. doi: 10.2147/ott.s178431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Loewen G., Jayawickramarajah J., Zhuo Y., Shan B. Functions of lncRNA HOTAIR in lung cancer. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2014;7(1) doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0090-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang Y., Jiang C., Yang Y., et al. Silencing of LncRNA-HOTAIR decreases drug resistance of non-small cell lung cancer cells by inactivating autophagy via suppressing the phosphorylation of ULK1. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2018;497(4):1003–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Uddin A., Chakraborty S. Role of miRNAs in lung cancer. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2018:1–10. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26607. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hatley M. E., Patrick D. M., Garcia M. R., et al. Modulation of K-Ras-dependent lung tumorigenesis by MicroRNA-21. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(3):282–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luo L., Zhang T., Liu H. B., et al. MiR-101 and Mcl-1 in non-small-cell lung cancer: expression profile and clinical significance. Medical Oncology. 2012;29(3):1681–1686. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Y., Li Y., Wu B., Shi C., Li C. MicroRNA-661 promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression by directly targeting RUNX3. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2017;16(2):2113–2120. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Florczuk M., Szpechcinski A., Chorostowska-Wynimko J. miRNAs as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in non-small cell lung cancer: current perspectives. Targeted Oncology. 2017;12(2):179–200. doi: 10.1007/s11523-017-0478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen L. L. The biogenesis and emerging roles of circular RNAs. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2016;17(4):205–211. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Braicu C., Zimta A. A., Harangus A., et al. The function of non-coding RNAs in lung cancer tumorigenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(5):p. 605. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Di X., Jin X., Li R., Zhao M., Wang K. CircRNAs and lung cancer: biomarkers and master regulators. Life Sciences. 2019;220:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jiang M. M., Mai Z. T., Wan S. Z., et al. Microarray profiles reveal that circular RNA hsa_circ_0007385 functions as an oncogene in non-small cell lung cancer tumorigenesis. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2018;144(4):667–674. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2576-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ma X. M., Yang X. D., Bao W. H., et al. Circular RNA circMAN2B2 facilitates lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion via miR-1275/FOXK1 axis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2018;498(4):1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.03.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Diaz-Lagares A., Mendez-Gonzalez J., Hervas D., et al. A novel epigenetic signature for early diagnosis in lung cancer. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2016;22:3361–3371. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhu Y., Li T., Chen G., et al. Identification of a serum microRNA expression signature for detection of lung cancer, involving miR-23b, miR-221, miR-148b and miR-423-3p. Lung Cancer. 2017;114:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu Z., Qiu M., Guo Y., et al. OTU deubiquitinase 4 is silenced and radiosensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells via inhibiting DNA repair. Cancer Cell International. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-0816-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li Y., Gu J., Xu F., Zhu Q., Ge D., Lu C. Novel methylation-driven genes identified as prognostic indicators for lung squamous cell carcinoma. American Journal of Translational Research. 2019;11(4):1997–2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shi Y. X., Yin J. Y., Shen Y., Zhang W., Zhou H. H., Liu Z. Q. Genome-scale analysis identifies NEK2, DLGAP5 and ECT2 as promising diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in human lung cancer. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):p. 8072. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08615-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guo X., Chen Z., Zhao L., Cheng D., Song W., Zhang X. Long non-coding RNA-HAGLR suppressed tumor growth of lung adenocarcinoma through epigenetically silencing E2F1. Experimental Cell Research. 2019;382(1) doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.06.006.111461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang Y., Roth J. A., Yu H., et al. A 5-microRNA signature identified from serum microRNA profiling predicts survival in patients with advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40(5):643–650. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgy132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hatzimichael E., Crook T. Cancer epigenetics: new therapies and new challenges. Journal of Drug Delivery. 2013;2013:9. doi: 10.1155/2013/529312.529312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu S. V., Fabbri M., Gitlitz B. J., Laird-Offringa I. A. Epigenetic therapy in lung cancer. Frontiers in Oncology. 2013;3:p. 135. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tang M., Xu W., Wang Q., Xiao W., Xu R. Potential of DNMT and its epigenetic regulation for lung cancer therapy. Current Genomics. 2009;10(5):336–352. doi: 10.2174/138920209788920994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Humeniuk R., Mishra P. J., Bertino J. R., Banerjee D. Molecular targets for epigenetic therapy of cancer. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2009;10(2):161–165. doi: 10.2174/138920109787315123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schiffmann I., Greve G., Jung M., Lübbert M. Epigenetic therapy approaches in non-small cell lung cancer: update and perspectives. Epigenetics. 2016;11(12):858–870. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1237345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vansteenkiste J., Van Cutsem E., Dumez H., et al. Early phase II trial of oral vorinostat in relapsed or refractory breast, colorectal, or non-small cell lung cancer. Investigational New Drugs. 2008;26(5):483–488. doi: 10.1007/s10637-008-9131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Juergens R. A., Wrangle J., Vendetti F. P., et al. Combination epigenetic therapy has efficacy in patients with refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discovery. 2011;1(7):598–607. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-11-0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huang D., Cui L., Ahmed S., et al. An overview of epigenetic agents and natural nutrition products targeting DNA methyltransferase, histone deacetylases and microRNAs. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2019;123:574–594. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Beg M. S., Brenner A. J., Sachdev J., et al. Phase I study of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, administered twice weekly in patients with advanced solid tumors. Investigational New Drugs. 2017;35(2):180–188. doi: 10.1007/s10637-016-0407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van Zandwijk N., Pavlakis N., Kao S., et al. Mesomir 1: a phase I study of targomirs in patients with refractory malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) and lung cancer (NSCLC) Annals of Oncology. 2015;26(2):p. 16. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv090.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lubin A., Zhang L., Chen H., White V. M., Gong F. A human XPC protein interactome—a resource. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;15(1):141–158. doi: 10.3390/ijms15010141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhao Y., Majid M. C., Soll J. M., Brickner J. R., Dango S., Mosammaparast N. Noncanonical regulation of alkylation damage resistance by the OTUD4 deubiquitinase. EMBO Journal. 2015;34(12):1687–1703. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu Y. Y., Han J. Y., Lin S. C., Liu Z. Y., Jiang W. T. Effect of CDH1 gene methylation on transforming growth factor (TGF-beta)-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cell line A549. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2014;13(4):8568–8576. doi: 10.4238/2014.february.13.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen L., Guo Q., Liu S., Yu Q. Clinicopathological significance and potential drug targeting of CDH1 in lung cancer: a meta-analysis and literature review. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2015;9:2171–2178. doi: 10.2147/dddt.s78537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li W., Deng J., Jiang P., Zeng X., Hu S., Tang J. Methylation of the RASSF1A and RARbeta genes as a candidate biomarker for lung cancer. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2012;3(6):1067–1071. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jiang A., Wang X., Shan X., et al. Curcumin reactivates silenced tumor suppressor gene RARbeta by reducing DNA methylation. Phytotherapy Research. 2015;29(8):1237–1245. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Virmani A. K., Rathi A., Zochbauer-Muller S., et al. Promoter methylation and silencing of the retinoic acid receptor-beta gene in lung carcinomas. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(16):1303–1307. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Licchesi J. D., Westra W. H., Hooker C. M., Machida E. O., Baylin S. B., Herman J. G. Epigenetic alteration of Wnt pathway antagonists in progressive glandular neoplasia of the lung. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(5):895–904. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stewart D. J. Wnt signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2014;106(1):p. djt356. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Um S. W., Kim Y., Lee B. B., et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation in bronchial washings. Clinical Epigenetics. 2018;10(1):p. 65. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0498-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Xu L., Lan H., Su Y., Li J., Wan J. Clinicopathological significance and potential drug target of RUNX3 in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2015;9:2855–2865. doi: 10.2147/dddt.s76358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jian S. F., Hsiao C. C., Chen S. Y., et al. Utilization of liquid chromatography mass spectrometry analyses to identify LKB1-APC interaction in modulating Wnt/beta-catenin pathway of lung cancer cells. Molecular Cancer Research. 2014;12:622–635. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.mcr-13-0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guo S., Tan L., Pu W., et al. Quantitative assessment of the diagnostic role of APC promoter methylation in non-small cell lung cancer. Clinical Epigenetics. 2014;6(1):p. 5. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Feng H., Zhang Z., Qing X., Wang X., Liang C., Liu D. Promoter methylation of APC and RAR-beta genes as prognostic markers in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2016;100(1):109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Huang Z., Lei W., Hu H. B., Zhang H., Zhu Y. H19 promotes non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) development through STAT3 signaling via sponging miR-17. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2018;233(10):6768–6776. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Barsyte-Lovejoy D., Lau S. K., Boutros P. C., et al. The c-myc oncogene directly induces the H19 noncoding RNA by allele-specific binding to potentiate tumorigenesis. Cancer Research. 2006;66(10):5330–5337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-06-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ren J., Fu J., Ma T., et al. LncRNA H19-elevated LIN28B promotes lung cancer progression through sequestering miR-196b. Cell Cycle. 2018;17(11):1372–1380. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1482137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yang T., Li H., Chen T., Ren H., Shi P., Chen M. LncRNA MALAT1 depressed chemo-sensitivity of NSCLC cells through directly functioning on miR-197-3p/p120 catenin axis. Molecules and cells. 2019;42(3):270–283. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2019.2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Li S., Ma F., Jiang K., Shan H., Shi M., Chen B. Long non-coding RNA metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 promotes lung adenocarcinoma by directly interacting with specificity protein 1. Cancer Science. 2018;109(5):1346–1356. doi: 10.1111/cas.13587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nie F. Q., Sun M., Yang J. S., et al. Long noncoding RNA ANRIL promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis by silencing KLF2 and P21 expression. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2015;14(1):268–277. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-14-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Naemura M., Murasaki C., Inoue Y., Okamoto H., Kotake Y. Long noncoding RNA ANRIL regulates proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer and cervical cancer cells. Anticancer Research. 2015;35(10):5377–5382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hu C., Jiang R., Cheng Z., et al. Ophiopogonin-B suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human lung adenocarcinoma cells via the linc00668/miR-432-5p/EMT axis. Journal of Cancer. 2019;10(13):2849–2856. doi: 10.7150/jca.31338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Li X., Zhang X., Yang C., Cui S., Shen Q., Xu S. The lncRNA RHPN1-AS1 downregulation promotes gefitinib resistance by targeting miR-299-3p/TNFSF12 pathway in NSCLC. Cell Cycle. 2018;17(14):1772–1783. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1496745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 119.Qin J., Ning H., Zhou Y., Hu Y., Yang L., Huang R. LncRNA MIR31HG overexpression serves as poor prognostic biomarker and promotes cells proliferation in lung adenocarcinoma. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2018;99:p. 363. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhou B., Wang D. M., Sun G. Z., Mei F. Y., Cui Y., Xu H. Y. Effect of miR-21 on apoptosis in lung cancer cell through inhibiting the PI3K/akt/NF-kappa B signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2018;46(3):999–1008. doi: 10.1159/000488831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Liu F., Cai Y., Rong X., et al. MiR-661 promotes tumor invasion and metastasis by directly inhibiting RB1 in non small cell lung cancer. Molecular Cancer. 2017;16(1):p. 122. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0698-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gao P., Wang H., Yu J., et al. miR-3607-3p suppresses non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by targeting TGFBR1 and CCNE2. PLoS Genetics. 2018;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007790.e1007790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 123.Chang H., Liu Y.-H., Wang L.-L., Wang J., Wang S.-F. MiR-182 promotes cell proliferation by suppressing FBXW7 and FBXW11 in non-small cell lung cancer. American Journal of Translational Research. 2018;10(4):1131–1142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fang H., Liu Y., He Y., et al. Extracellular vesicle delivered miR5055p, as a diagnostic biomarker of early lung adenocarcinoma, inhibits cell apoptosis by targeting TP53AIP1. International Journal of Oncology. 2019;54:1821–1832. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mo D., Gu B., Gong X., et al. miR-1290 is a potential prognostic biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2015;7(9):1570–1579. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.09.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yoo J. K., Lee J. M., Kang S. H., et al. The novel microRNA hsa-miR-CHA1 regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis in human lung cancer by targeting XIAP. Lung Cancer. 2019;132:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]