Abstract

Objective

To study the relationship between maternal affective disorders (AD) before and during pregnancy, and pre-term birth.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Location

Sexual and reproductive health units at the Institut Català de la Salut (ICS) in Catalonia, Spain.

Participants

Pregnant women with a result of live-born child from 1/1/2012 to 30/10/2015.

Interventions

Data were obtained from the ICS Primary Care electronic medical record.

Main measurements

Diagnosis of AD before and during pregnancy, months of pregnancy, and possible confusion factors were collected. Descriptive statistical analysis (median, interquartile range, and absolute and relative frequency), bivariate analysis (Wilcoxon test and Chi-square test), and multivariate analysis (logistic regression) were performed.

Results

102,086 women presented valid information for the study. Prevalence of AD during pregnancy was 3.5% (4.29% in pre-term and 3.46% in term births; p < 0.004). Pregnant women with pre-term births presented a higher age, smoking habit, lower inter-pregnancy interval, and a lower socio-economic status. Pre-term birth was significantly associated to previous history of stress and dissociative disorder (SDD), anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and eating disorders (ED), and use of antidepressants. It was also associated to abuse of alcohol, smoking, and use of psychoactive substances, as well as SDD, ED, use of antipsychotics, and divorce during pregnancy. Multivariate analysis confirmed the relationship between pre-term birth and history of AD, SDD, ED, and smoking, but not with AD during pregnancy.

Conclusions

Examining the previous history of SDD and ED in pregnant women, and SDD, and ED during pregnancy is highly relevant to avoid pre-term birth.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Affective disorders, Infant, Premature, Risk factors, Antidepressive agents

Resumen

Objetivo

Estudiar la relación entre diagnósticos de trastornos afectivos (TA) antes y durante el embarazo, y factores de confusión con prematuridad del neonato.

Diseño

Estudio observacional retrospectivo.

Emplazamiento

Servicios de atención sexual y reproductiva del Institut Català de la Salut (ICS) en Cataluña, España.

Participantes

Embarazadas atendidas con resultado de hijo vivo del 1/1/2012 al 30/10/2015.

Intervenciones

Datos recogidos en la base de datos de la historia clínica informatizada.

Mediciones

Se recogió los diagnósticos de TA antes y durante el embarazo, meses de gestación y posibles factores de confusión. Se realizó análisis estadístico descriptivo (mediana y rango intercuartílico y frecuencias absoluta y relativa), bivariante (test de Wilcoxon y Chi-cuadrado) y multivariante (regresión logística).

Resultados

Ciento dos mil ochenta y seis mujeres presentaban información válida para el estudio. La prevalencia de TA durante el embarazo fue del 3,5% (4,29% en prematuros y 3,46% en a término; p < 0,004). Las embarazadas con partos prematuros presentan mayor edad, más tabaquismo, menor tiempo entre embarazos y menor nivel socioeconómico. La prematuridad se asoció a antecedentes previos de trastorno por estrés y disociativo (TED), de ansiedad y obsesivo-compulsivo, de conducta alimentaria (TCA) y uso de antidepresivos. También a abuso de alcohol, tabaco y sustancias psicoactivas; TED, TCA, uso de antipsicóticos y divorcio durante el embarazo. El análisis multivariante confirmó la relación de prematuridad con antecedentes de TA, TED, TCA y tabaquismo, pero no con TA durante el embarazo.

Conclusiones

Es importante explorar antecedentes de TED y TA en la embarazada y los TED durante el embarazo, para disminuir la prematuridad.

Palabras clave: Embarazo, Trastornos psicóticos afectivos, Recién nacido Prematuro, Factores de riesgo, Antidepresivos

Introduction

Depression is the most frequent mental disorder in women. It may alter the course of pregnancy, affect the foetus, and the newborn, having consequences even on adolescence.1, 2 Prevalence of depression during pregnancy ranges from 4.8% to 33.2%,3 with under 50% of cases identified in the everyday clinical practice.4 Depression and bipolar disorder have been associated to pre-term birth.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Studies on the relationship between affective disorders and pre-term birth, conducted in the Mediterranean and South European countries, and included in systematic reviews, are scarce, therefore, no data on this matter are available in our country. Pre-term birth has been associated to prolonged stays at paediatric intensive care units or neonatal departments, a higher incidence of infection, and of respiratory, digestive, ophthalmologic, psychomotor conditions, etc.,11 resulting in a remarkable impact on the health care system.

Other clinical obstetric and therapeutic factors associated to pre-term birth are collected on the Clinical Practice Guideline for care in Pregnancy and Puerperium in the Spanish National Health Service (NHS),12 on the ‘Protocol de Seguiment de l’embaràs a Catalunya’ (Protocol on pregnancy monitoring in Catalonia),13 and on numerous publications14, 15 (Table S1). Moreover, pre-term birth has been associated with stress,16, 17 and low socio-economic status.7

The Spanish NHS guideline systematically evaluates postpartum depression, but it does not recommend a similar population screening during pregnancy, unlike other countries. It neither recommends a systematic mental health examination on women of childbearing age.

The current study aims to study the relationship between maternal affective disorders (AD) and pre-term birth, controlling by the confusion factors associated to pre-term birth, and differentiating between those factors which appeared priorly, and those presenting during pregnancy. Since mental health disorders are not as extensively investigated as physical conditions, on the patient anamnesis performed on women in family and maternal and child primary healthcare services, we will dedicate special attention to them.

This study is framed within the primary healthcare area, being its implementation necessary since to date, no similar clinical study has been performed in our country.

The aim is to study the relationship between maternal affective disorders (AD) before and during pregnancy, and pre-term birth.

Material and methods

Design, area of study, and research subjects

Retrospective observational study conducted in the primary health care area.

Data were obtained from the Information System for the Enhancement of Research in Primary Care (SIDIAP) database, with an assigned population in 2012 of 5,835,000 patients (80% of the total population in Catalonia). This database is supplied, among other, by information from the Primary Care electronic medical records (e-CAP), and from the Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Program (ASSIR) of the Catalan Institute of Health (ICS), used by obstetricians, gynaecologists, and midwives in primary care. The ASSIR records include data on pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum monitoring from women who attended the primary health care services of the ICS,18 accounting for 65.7% term pregnancies in Catalonia, over the period of our study.19

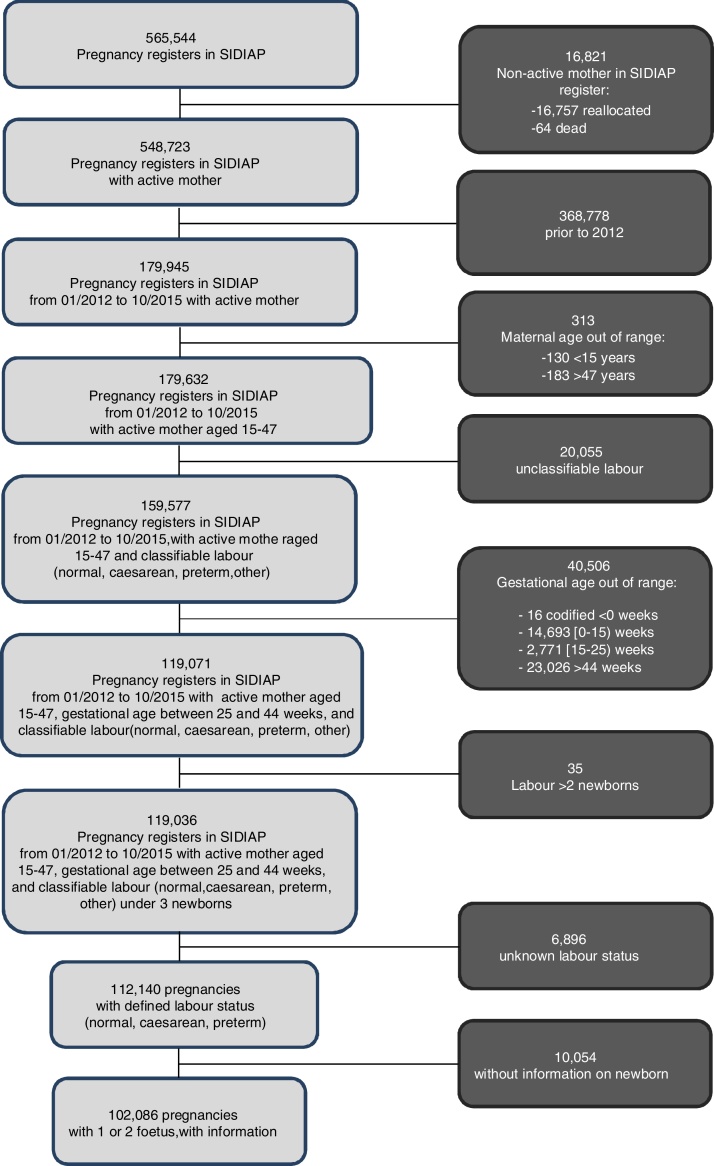

All pregnant women registered in the SIDIAP, aged 15–47, who gave birth to live-born children in Catalonia from 1st January 2012 to 30 October 2015, with a gestational age over 25 weeks and under 44 weeks, and with two foetuses at most, were included in the study.

Variables

Pre-term birth was defined as gestational age under 37 weeks, based on the number of days from the date of last menstruation to the date of birth.

AD included the following ICD-10 codes: F30 (Manic episode), F31 (Bipolar disorder), F32 (Depressive disorders), F33 (Recurrent depressive disorder), F34 (Persistent mood affective disorder), F38 (Other mood affective disorders), F39 (Unspecified mood affective disorders), presenting before pregnancy (at any time of life) or during pregnancy.

Socio-economic status was classified according to the Deprivation index MEDEA,20 presented in quintiles (the highest quintile, the lower socio-economic status). All the variables related to pre-term birth found on the clinical guides, and on the conducted bibliographic search, were collected7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 (Table S1). Considering the ICD-10,099 code includes all mental disorders, those most discussed and controverted on the reviewed literature, were chosen. Those AD interrelated, especially when scarce in number, were gathered, namely, stress and dissociative disorder (SDD), eating disorder (ED), anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), etc. Whether these diagnoses were active before or during pregnancy was taken into consideration.

Finally, all treatments related to pre-term birth, based on clinical guides and literature, were registered, and coded according to the “Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification” (WHOCC-ATC)21 (Table S2). It was also recorded whether medication was taken before or during pregnancy.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis, showing median and interquartile range for numeric variables, and absolute and relative frequency for categorical variables; A bivariate analysis according to pre-term birth, was performed, through Wilcoxon test for numeric variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

A multivariate logistic regression model was built (final model obtained by an AIC stepwise backwards variable selection model from all statistically and clinically relevant variables on the bivariate analysis), without including possible interactions between them.

All analyses were conducted by complete case (without missing values being treated). Significance level of 0.05 was considered as indicator of statistically significant differences. Treatment of data and statistical analyses were performed using software R 3.2.4-revised.

Study schema. Retrospective observational study with the aim to investigate the relationship between maternal affective disorders (AD) before and during pregnancy, and pre-term birth.

Results

Out of the 119,036 pregnancies which fulfilled the inclusion criteria, valid information for the study was obtained from 102,086 women (85%). The prevalence of affective disorders during pregnancy was 3.5%, and the prevalence of pre-term birth 4.2%. Patients who presented pre-term birth showed a significantly higher age, a lower socio-economic status, a higher history of previous pre-term birth, a higher history of abortion, a shorter interval between pregnancies, and a higher rate of twin pregnancies (Table 1). Pre-term birth was also significantly associated with history of AD, OCD, SDD, smoking, and ED, among other (Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive global and bivariate analysis of maternal characteristics, previous pregnancies, and labour regarding preterm birth.

| N = 102,086 | Missing | Global (n = 102,086) | Normal (n = 97,800) | Preterm (n = 4,286) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||

| Agea | 0 | 31.00 [27.00, 35.00] | 31.00 [27.00, 35.00] | 32.00 [28.00, 36.00] | <0.001 |

| MEDEA deprivation index | 0 | 0.038 | |||

| Rural | 15,487 (15.17%) | 14,804 (15.14%) | 683 (15.94%) | ||

| Quintile 1 (less disadvantaged) | 9,553 (9.36%) | 9,188 (9.39%) | 365 (8.52%) | ||

| Quintile 2 | 24,866 (24.36%) | 23,864 (24.40%) | 1,002 (23.38%) | ||

| Quintile 3 | 14,508 (14.21%) | 13,913 (14.23%) | 595 (13.88%) | ||

| Quintile 4 | 17,236 (16.88%) | 16,514 (16.89%) | 722 (16.85%) | ||

| Quintile 5 (more disadvantaged) | 20,436 (20.02%) | 19,517 (19.96%) | 919 (21.44%) | ||

| Partnership status | 0 | 0.468 | |||

| Single | 37,279 (36.52%) | 35,691 (36.49%) | 1,588 (37.05%) | ||

| Partner | 64,807 (63.48%) | 62,109 (63.51%) | 2,698 (62.95%) | ||

| Previous delivery | |||||

| Term deliveryb | 1,334 | 1.07 (1.01) | 1.08 (1.01) | 0.81 (0.99) | <0.001 |

| Preterm deliveryb | 1,334 | 0.03 (0.19) | 0.02 (0.16) | 0.22 (0.52) | <0.001 |

| Abortionb | 1,334 | 0.46 (0.79) | 0.46 (0.79) | 0.53 (0.88) | <0.001 |

| Live bornb | 1,334 | 1.08 (1.01) | 1.09 (1.00) | 0.98 (1.02) | <0.001 |

| Inter-pregnancy interval | 0 | <0.001 | |||

| (>18 months) | 85,813 (84.06%) | 82,292 (84.14%) | 3,521 (82.15%) | ||

| [12–18] months | 5,334 (5.23%) | 5,102 (5.22%) | 232 (5.41%) | ||

| [0–12] months | 10,939 (10.72%) | 10,406 (10.64%) | 533 (12.44%) | ||

| Delivery characteristics | |||||

| Type | 14,439 | <0.001 | |||

| Eutocic | 56,808 (64.81%) | 54,974 (65.36%) | 1,834 (51.81%) | ||

| Dystocic | 30,839 (35.19%) | 29,133 (34.64%) | 1,706 (48.19%) | ||

| Number of foetuses | 0 | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 100,624 (98.57%) | 96,872 (99.05%) | 3,752 (87.54%) | ||

| 2 | 1,462 (1.43%) | 928 (0.95%) | 534 (12.46%) | ||

Qualitative variables are expressed in absolute and relative frequency for each category, and numeric variables are expressed in (a) median and interquartile range, or (b) media and standard deviation. Variable distribution between preterm and term labour groups is compared by Wilcoxon test for numeric variables, and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Table 2.

[ll1]Health conditions before birth. Descriptive and bivariate analysis according to preterm birth.

| Previous history |

During pregnancy |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Normal (n = 97,800) | Preterm (n = 4,286) | p-Value | Global | Normal (n = 97,800) | Preterm (n = 4,286) | p-Value | |

| Affective disorder | 1,631 (1.60%) | 1,533 (1.57%) | 98 (2.29%) | <0.001 | 3,571 (3.50%) | 3,387 (3.46%) | 184 (4.29%) | 0.004 |

| Anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder | 6,775 (6.64%) | 6,427 (6.57%) | 348 (8.12%) | <0.001 | 14,996 (14.69%) | 14,294 (14.62%) | 702 (16.38%) | 0.002 |

| Dissociative and stress disorder | 746 (0.73%) | 695 (0.71%) | 51 (1.19%) | <0.001 | 1,922 (1.88%) | 1,818 (1.86%) | 104 (2.43%) | 0.009 |

| Smoker | 7,962 (7.80%) | 7,623 (7.79%) | 339 (7.91%) | 0.806 | 22,533 (22.07%) | 21,491 (21.97%) | 1,042 (24.31%) | <0.001 |

| Non-smoker | 2,455 (2.40%) | 2,372 (2.43%) | 83 (1.94%) | 0.046 | 47,962 (46.98%) | 46,045 (47.08%) | 1,917 (44.73%) | 0.003 |

| Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of tobacco | 2,869 (2.81%) | 2,756 (2.82%) | 113 (2.64%) | 0.511 | 15,961 (15.63%) | 15,217 (15.56%) | 744 (17.36%) | 0.002 |

| Eating disorder | 207 (0.20%) | 192 (0.20%) | 15 (0.35%) | 0.044 | 833 (0.82%) | 803 (0.82%) | 30 (0.70%) | 0.438 |

| Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of psychoactive substances | 125 (0.12%) | 120 (0.12%) | 5 (0.12%) | 1.000 | 451 (0.44%) | 422 (0.43%) | 29 (0.68%) | 0.024 |

| Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol | 69 (0.07%) | 63 (0.06%) | 6 (0.14%) | 0.118 | 277 (0.27%) | 250 (0.26%) | 27 (0.63%) | <0.001 |

| Divorce | 287 (0.28%) | 275 (0.28%) | 12 (0.28%) | 1.000 | 1,468 (1.44%) | 1,387 (1.42%) | 81 (1.89%) | 0.013 |

| In Vitro fertilization | 147 (0.14%) | 135 (0.14%) | 12 (0.28%) | 0.028 | 573 (0.56%) | 503 (0.51%) | 70 (1.63%) | <0.001 |

| Caesarean | 1,033 (1.01%) | 973 (0.99%) | 60 (1.40%) | 0.012 | 334 (0.33%) | 322 (0.33%) | 12 (0.28%) | 0.677 |

| Twin pregnancy | 39 (0.04%) | 36 (0.04%) | 3 (0.07%) | 0.491 | 169 (0.17%) | 114 (0.12%) | 55 (1.28%) | <0.001 |

| Placental pathology | 13 (0.01%) | 12 (0.01%) | 1 (0.02%) | 1.000 | 23 (0.02%) | 19 (0.02%) | 4 (0.09%) | 0.008 |

| Placenta praevia, detachment, antepartum haemorrhage | 780 (0.76%) | 752 (0.77%) | 28 (0.65%) | 0.446 | 2,623 (2.57%) | 2,413 (2.47%) | 210 (4.90%) | <0.001 |

| Pre-eclampsia-Eclampsia | 417 (0.41%) | 383 (0.39%) | 34 (0.79%) | <0.001 | 1,046 (1.02%) | 892 (0.91%) | 154 (3.59%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 110 (0.11%) | 101 (0.10%) | 9 (0.21%) | 0.065 | 852 (0.83%) | 751 (0.77%) | 101 (2.36%) | <0.001 |

| Glomerular disease, tubulo-interstitial disease, lithiasis, other | 1,432 (1.40%) | 1,366 (1.40%) | 66 (1.54%) | 0.475 | 1,608 (1.58%) | 1,524 (1.56%) | 84 (1.96%) | 0.045 |

| Metabolic disorder | 310 (0.30%) | 293 (0.30%) | 17 (0.40%) | 0.323 | 3,829 (3.75%) | 3,603 (3.68%) | 226 (5.27%) | <0.001 |

| Viral Hepatitis | 270 (0.26%) | 249 (0.25%) | 21 (0.49%) | 0.005 | 769 (0.75%) | 735 (0.75%) | 34 (0.79%) | 0.827 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 49 (0.05%) | 44 (0.04%) | 5 (0.12%) | 0.082 | 372 (0.36%) | 333 (0.34%) | 39 (0.91%) | <0.001 |

| Toxic liver disease | 5 (0.00%) | 3 (0.00%) | 2 (0.05%) | 0.004 | 8 (0.01%) | 7 (0.01%) | 1 (0.02%) | 0.772 |

| Sexual transmission disease | 251 (0.25%) | 233 (0.24%) | 18 (0.42%) | 0.028 | 789 (0.77%) | 761 (0.78%) | 28 (0.65%) | 0.410 |

| Viral disease | 14,230 (13.94%) | 13,577 (13.88%) | 653 (15.24%) | 0.013 | 5,219 (5.11%) | 4,982 (5.09%) | 237 (5.53%) | 0.218 |

| Mycosis (Aspergillus, etc.) | 47 (0.05%) | 46 (0.05%) | 1 (0.02%) | 0.731 | 96 (0.09%) | 86 (0.09%) | 10 (0.23%) | 0.005 |

| Blood disorder | 58 (0.06%) | 52 (0.05%) | 6 (0.14%) | 0.045 | 479 (0.47%) | 459 (0.47%) | 20 (0.47%) | 1.000 |

| Congenital malformation | 126 (0.12%) | 119 (0.12%) | 7 (0.16%) | 0.591 | 1,127 (1.10%) | 1,062 (1.09%) | 65 (1.52%) | 0.010 |

| Cerebral palsy and other | 4 (0.00%) | 4 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1.000 | 29 (0.03%) | 25 (0.03%) | 4 (0.09%) | 0.035 |

| Vestibular disorder | 2325 (2.28%) | 2,208 (2.26%) | 117 (2.73%) | 0.048 | 1,220 (1.20%) | 1,165 (1.19%) | 55 (1.28%) | 0.638 |

| Benign tumoura | 493 (0.48%) | 452 (0.46%) | 41 (0.96%) | <0.001 | 2319 (2.27%) | 2,198 (2.25%) | 121 (2.82%) | 0.015 |

| Tumour | 37 (0.04%) | 35 (0.04%) | 2 (0.05%) | 1.000 | 113 (0.11%) | 102 (0.10%) | 11 (0.26%) | 0.007 |

Digestive system, respiratory, intrathoracic, bone and cartilage, lipomatous, mesothelial, conjunctive, ovarian, uterus, meningeal, encephalous.

Absolute and relative frequency of women presenting the characteristic are shown for each variable. Variable distribution between preterm and term labour groups is compared by Chi-square test. This description and test are conducted on variables prior to pregnancy (previous history) and variables during pregnancy.

With regard to health conditions during pregnancy (Table 2), pre-term birth was bivariately associated with anxiety, OCD, AD, SDD, divorce, smoking, mental disorder due to psychoactive substance use, abuse of alcohol and tobacco, among other. It was also associated with history of antidepressant intake and use of antipsychotics during pregnancy, among other (Table 3).

Table 3.

Use of medication prior to birth. Descriptive and bivariate analysis according to preterm birth.

| Previous history |

During pregnancy |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global (n = 102,086) | Normal (n = 97,800) | Preterm (n = 4,286) | p-Value | Global (n = 102,086) | Normal (n = 97,800) | Preterm (n = 4,286) | p-value | |

| Anticoagulants | 3,548 (3.48%) | 3,385 (3.46%) | 163 (3.80%) | 0.249 | 1,770 (1.73%) | 1,578 (1.61%) | 192 (4.48%) | <0.001 |

| Antidepressants | 11,529 (11.29%) | 10,962 (11.21%) | 567 (13.23%) | <0.001 | 4,143 (4.06%) | 3,936 (4.02%) | 207 (4.83%) | 0.010 |

| Androgens | 21,109 (20.68%) | 20,253 (20.71%) | 856 (19.97%) | 0.252 | 9,125 (8.94%) | 8,589 (8.78%) | 536 (12.51%) | <0.001 |

| Antipsychotics | 2,179 (2.13%) | 2,070 (2.12%) | 109 (2.54%) | 0.066 | 407 (0.40%) | 374 (0.38%) | 33 (0.77%) | <0.001 |

| ACEI | 382 (0.37%) | 337 (0.34%) | 45 (1.05%) | <0.001 | 191 (0.19%) | 160 (0.16%) | 31 (0.72%) | <0.001 |

| Progestagens | 18,744 (18.36%) | 17,993 (18.40%) | 751 (17.52%) | 0.153 | 8,191 (8.02%) | 7,704 (7.88%) | 487 (11.36%) | <0.001 |

Absolute and relative frequency of use, are shown for each medication. Variable distribution between preterm and term labour groups is compared by Chi-square test. This description and test are conducted on use of medication prior to pregnancy (previous history) and during pregnancy.

ACEI = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors.

Pre-term birth was significantly associated with history of AD, SDD, ED, and smoking among other, in the final multivariate model. It was also associated with presence of smoking and mental disorder due to use of alcohol during pregnancy, among other (Table 4). The association between AD before pregnancy and pre-term birth, in terms of punctual estimation of the adjusted OR (1.32 95%CI: [1.04, 1.64]) was inferior than Eclampsia (3.22 [2.63, 3.90]), DM (2.31 [1.56, 3.31]), and HTA (2.15 [1.64, 2.79]) and Placenta praevia, detachment, antepartum haemorrhage (1.80 [1.53, 2.11]), and superior than smoking (non-smokers OR: 0.92 [0.86, 0.98]). Presence of SDD during pregnancy was relevant, providing plausibility to the model, although its marginal effect did not reach statistical significance. Association between AD during pregnancy and pre-term birth was not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis on health conditions prior and during pregnancy and preterm birth.

| Odds Ratio [CI95%] | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (Independent term) | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | <0.001 | |

| Affective disorders during pregnancy | 1.07 [0.90, 1.26] | 0.413 | |

| Previous births characteristics | Term birth | 0.54 [0.45, 0.63] | <0.001 |

| Preterm birth | 4.68 [4.00, 5.45] | <0.001 | |

| Abortion | 1.07 [1.03, 1.11] | 0.001 | |

| Live-born | 1.44 [1.21, 1.71] | <0.001 | |

| Socio-economic status | Rural | -reference- | |

| Quintile 1 (less disadvantaged) | 0.92 [0.80, 1.05] | 0.231 | |

| Quintile 2 | 0.92 [0.82, 1.02] | 0.117 | |

| Quintile 3 | 0.91 [0.81, 1.03] | 0.144 | |

| Quintile 4 | 0.98 [0.88, 1.10] | 0.789 | |

| Quintile 5 (more disadvantaged) | 1.09 [0.97, 1.21] | 0.136 | |

| Inter-pregnancy interval | Without short interval | -reference- | |

| 12 to 18 months | 0.98 [0.84, 1.14] | 0.822 | |

| Under 12 months | 1.19 [1.07, 1.32] | <0.001 | |

| Number of foetuses | 14.32 [12.37, 16.55] | <0.001 | |

| Previous history | |||

| Affective disorder | 1.32 [1.04, 1.64] | 0.017 | |

| Dissociative and stress disorder | 1.41 [1.02, 1.91] | 0.030 | |

| Non-smoker | 0.72 [0.56, 0.91] | 0.007 | |

| Eating disorder | 1.91 [1.05, 3.20] | 0.022 | |

| Viral Hepatitis | 1.79 [1.04, 2.90] | 0.025 | |

| Toxic liver disease | 12.75 [1.53, 83.93] | 0.009 | |

| Benign tumoura | 1.70 [1.18, 2.38] | 0.003 | |

| During pregnancy | |||

| Medication | |||

| Anticoagulants | 1.39 [1.15, 1.67] | <0.001 | |

| Androgens | 1.23 [1.10, 1.36] | <0.001 | |

| Antipsychotics | 1.61 [1.05, 2.36] | 0.021 | |

| ACEI | 1.88 [1.13, 3.03] | 0.012 | |

| Health conditions | |||

| Dissociative and stress disorder | 1.24 [0.99, 1.53] | 0.051 | |

| Non-smoker | 0.92 [0.86, 0.98] | 0.010 | |

| Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol | 1.92 [1.20, 2.93] | 0.004 | |

| In Vitro fertilization | 1.46 [1.05, 2.00] | 0.021 | |

| Placenta praevia, detachment, antepartum haemorrhage | 1.80 [1.53, 2.11] | <0.001 | |

| Eclampsia | 3.22 [2.63, 3.90] | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 2.15 [1.64, 2.79] | <0.001 | |

| Glomerular disease, tubulo-interstitial disease, lithiasis, other | 1.20 [0.94, 1.52] | 0.128 | |

| Metabolic disorder | 1.30 [1.11, 1.51] | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2.31 [1.56, 3.31] | <0.001 | |

| Mycosis (Aspergillus, etc.) | 3.35 [1.60, 6.26] | <0.001 | |

| Congenital malformation | 1.24 [0.94, 1.61] | 0.122 | |

| Cerebral palsy and other | 2.72 [0.74, 7.74] | 0.088 | |

| Tumour | 2.38 [1.12, 4.51] | 0.014 | |

Digestive system, respiratory, intrathoracic, bone and cartilage, lipomatous, mesothelial, conjunctive, ovarian, uterus, meningeal, encephalous.

ACEI = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors.

Results of the multivariate logistic regression model on preterm birth. Final model obtained by “stepwise backwards” variable selection model based on the “Akaike Information Criteria” from all statistically significant and clinically relevant variables on the bivariate analysis, as explicative variables. Results are presented in “Odds Ratio”, with a confidence interval of 95%, estimated as the exponential of the obtained coefficient from the multivariate logistic regression model, and p-value of its statistical significance.

Discussion

This study shows an association between previous history of maternal AD and pre-term birth. The prevalence of pre-term birth obtained in our study was 4.2%, lower than the 7% expected.19 This may have been due to the restrictive inclusion criteria considered in the study, and to the fact that in 2012 not all ASSIR relied on the same electronic register.

The prevalence of AD during pregnancy obtained in our study is considerably lower than that published on most studies which use depression scales without diagnostic confirmation (often self-reported),3, 4 being comparable to that reported in studies which use clinical diagnoses,22 and even to that found in studies performed in psychiatric in-patient wards.8

Most widely used health evaluation instruments present sensitivity and specificity values which are far from ideal. Therefore, the ‘Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale’ (EPDS) shows a sensitivity of 0.72 and a specificity of 0.85 for the 10 cut-off point for ‘minor’ or ‘major depression’ on the English version, and 0.81 and 0.92 respectively, on the non-English versions4; The sensitivity and specificity values for the ‘Patient Health Questionnaire’ (PHQ) are 0.79 and 0.75 respectively. Accordingly, the use of this type of screening tools -with specificity far from ideal- to screen population for low prevalence conditions automatically triggers prevalence values.

Whereas the definition of AD, would lead one to expect a higher prevalence than that found in those studies limited to depression (most of them), it is to be expected a lower prevalence of AD in the population seen in primary care (general population) than in the population seen in specialized centres.

Despite identifying a bivariate association between AD during pregnancy and pre-term birth initially, we did not observe this association on the multivariate analysis, after considering history of AD (prior to pregnancy), and other factors like the use of relevant medication, whose bivariate association with pre-term birth had also resulted significant. These results contradict the findings of the two meta-analysis published on this matter23, 24; although the authors themselves recognize their studies’ limitations: Grigoriadis23 concluded that the association was modest and the quality of evidence insufficient, and Grote24 reported lack of homogeneity among the evaluated studies. Both considered significantly fewer confusion factors than our work, which may explain this assumed difference.

However, our findings are consistent with more recent publications: Mei-Danobserved an association between history of maternal AD and pre-term birth, after comparing pregnant women who had been hospitalized due to bipolar disorder or major depression within the 5 years prior to pregnancy, with those without documented history of mental disorder. We consider that the higher the diagnostic specificity, the stronger this association becomes. Furthermore, Mannisto,22 observed an association between pre-term birth and maternal depression or bipolar disorder, based on electronic medical records and maternal psychiatric diagnoses from discharge summaries. Räisänen7 found a significant association between depression and pre-term birth, being smoking a relevant contributing factor, and history of depression prior to pregnancy the risk factor with the strongest association.

On the other hand, considering the generalized concept that prevalence of depression may be lower in the Mediterranean area, since our study was conducted in a Spanish population, we may expect a lower rate of AD than that found in North European or North American populations. However, last report from the WHO contradicts this assumption,25 having reported a higher relevance of low socio-economic status on the prevalence of this disorder, regardless of the country in which the study was conducted. Our work includes a population from all socio-economic status, which may explain the lower prevalence of depression, and is novel since addresses pregnant women resident in Catalonia.

Some authors have observed association between low socio-economic status (LSES) and situations of chronic stress, and between both with depression and pre-term birth.16, 17 In our study both LSES and diagnosis of SDD were associated to pre-term birth in the bivariate analysis. Multivariate analysis showed association between previous history of SDD and pre-term birth; however, the association of SDD during pregnancy with pre-term birth was not statistically significant, although by a very small margin. Most authors underline the relevance of identifying and alleviating exposure to stress during pregnancy, as far as possible, to reduce pre-term birth26; our results demonstrate the importance of evaluating the presentation of these disorders prior to pregnancy.

With regards to use of antidepressants, two meta-analysis recently conducted on the antidepressant-pre-term birth association, Huang and Eke,27, 28 considering exclusively selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), found an association between the use of SSRIs and pre-term birth. Viktorin, just observed a small reduction in gestational age associated to SSRIs.29 Sujan published in 2017 a retrospective cohort study, in which association between use of antidepressants, in general, during the first trimester of pregnancy and pre-term birth was observed.30 Our results, considering all antidepressants – except mood stabilizers-are consistent with these findings in the bivariate analysis, although do not coincide in the multivariate analysis. This discrepancy suggests the need to conduct further studies on the effect of the various antidepressant drugs on pre-term birth.

With reference to the relationship between use of antipsychotic medication during pregnancy and pre-term birth, we observed a statistically significant association, consistent with the findings of Galbally.14 It seems sensible to follow the general tendency to evaluate the risk-benefit relationship of using this medication in the pregnant woman who needs it, thoroughly and individually.31

One of the limitations of this study is the possible existence of incorrect or unregistered diagnoses, inherent to the use of electronic medical. In primary care settings, the data are entered by general practitioners, due to their own diagnosis, or because they have seen it in specialist reports or hospital discharge reports (in these last two cases the data are not downloaded automatically in the computerized records of primary care, with the consequent delay in the coding of hospital and specialist diagnoses). This can also ignore the diagnoses made in private care and not seen in primary care. And finally, it is also of note that data obtained from ASSIR of 2012 were incomplete, as the ASSIR electronic medical records were not homogeneous then.

Although the big sample size and representativeness of the study is an important strength, it must be advised that it can affect to the statistical signification of tests, easily leading to significance. Nevertheless (and keeping that in mind when valuing p-values), multivariate regression model was selected according to Akaike Information Criteria, and variables were included or not in the final model with disregard of their p-values.

On the other hand, our multivariate analysis only took into account the effect of the independent variables without interaction among them; since being such a large number, made it practically impossible to examine all variables two by two. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, it was considered inadequate to force a hypothesis on a limited number of possible interactions.

Nevertheless, the SIDIAP data base has been widely validated. Unlike other data bases, all primary care professionals in the ICS participate in it, not only voluntaries; and benefits from a first-rate anonymity system,18 which can open the way to conduct further research in our line, and in other areas where similar data bases – which include most of the population treated in the primary healthcare – may be established.

In conclusion, a previous history of AD in pregnant women is associated to pre-term birth. Classically, general habits and physical conditions have received more attention when evaluating health in pregnancy. This study demonstrates that, at least regarding avoiding pre-term birth and its severe consequences, to investigate the history of affective disorders, and the psychosocial environment in the pregnant woman is of great relevance, considering the potential stressful situations which may affect the course of pregnancy.

We coincide with some authors in that the aforementioned should be explored within a general examination, in a trusted environment, within the framework of the appropriate physician-patient relationship in primary care; paying attention to avoid that the patient may feel stigmatized or fear social services intervention.32 This becomes easier if we regard that any women of childbearing age can be a mother, and establish this desirable relationship from adolescence, whenever possible. A thorough anamnesis, which includes psychosocial factors – like the already available in many primary care devices, which have not received the attention they deserve – is undoubtedly, a suitable instrument to perform this task.

Key Points

The known on the subject:

Depression is the most frequent mental disorder in women and it may alter the course of pregnancy, affect the foetus, and the newborn.

Studies on the relationship between affective disorders and pre-term birth are scarce, therefore, and few data on this matter are available in our country.

The Spanish NHS guideline systematically evaluates postpartum depression, but it does not recommend a similar population screening during pregnancy, unlike other countries.

What does this study contribute?

This study shows an association between previous history of maternal affective disorders and pre-term birth.

To investigate the history of affective disorders, and the psychosocial environment in the pregnant woman is of great relevance, considering the potential stressful situations which may affect the course of pregnancy and avoiding pre-term birth and its severe consequences.

A thorough anamnesis, which includes psychosocial factors – like the already available in many primary care devices, which have not received the attention they deserve – is undoubtedly, a suitable instrument to perform this task.

Funding

This study received a research grant from the SIDIAP (Information System for the Enhancement of Research in Primary Care) of the University Institute for Research in Primary Care (IDIAP) Jordi Gol, in its 4th call for 2014.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.aprim.2018.06.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Depression, Fact sheet. Updated February 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en [accessed 26.06.17].

- 2.World Health Organization. Maternal and child mental health. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en [accessed 26.06.17].

- 3.Underwood L., Waldie K., D'Souza S., Peterson E., Morton S. A review of longitudinal studies on antenatal and postnatal depression. Arch Women's Ment Health. 2016;19:711–720. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0629-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor E., Rossom R.C., Henninger M., Groom H.C., Burda B.U. Primary care screening for and treatment of Depression in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315:388–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Littlewood E., Ali S., Ansell P., Dyson L., Gascoyne S., Hewitt C. BaBY PaNDA study team Identification of depression in women during pregnancy and the early postnatal period using the Whooley questions and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depresssion Scale: protocol for the Born and Bred in Yorkshire: Perinatal Depresssion Diagnostic Accuracy (Baby Panda) study. Br Med J Open. 2016;6:e011223. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibañez G., Charles M.A., Forhan A., Magnin G., Thiebaugeorges O., Kaminski M., EDEN Mother-Child Cohort Study Group Depression and anxiety in women during pregnancy and neonatal outcome: data from the EDEN mother-child cohort. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:643–649. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Räisänen S., Lehto S.M., Nielsen H.S., Gissler M., Kramer M.R., Heinonen S. Risk factors for and perinatal outcomes of major depression during pregnancy: a population-based analysis during 2002–2010 in Finland. Br Med J Open. 2014;4:e004883. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mei-Dan E., Ray J.G., Vigod S.N. Perinatal outcomes among women with bipolar disorder: a population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:367. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.020. E1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liou S.R., Wang P., Cheng C.Y. Effects of prenatal maternal mental distress on birth outcomes. Women Birth. 2016;29:376–380. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navaratne P., Foo X.Y., Kumar S. Impact of a high Edimburg Postnatal Depression Scale score on obstetric and perinatal outcomes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33544. doi: 10.1038/srep33544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen T.N., Hawgood S., Clyman R.I., Evans N., Warner B., Bada H.S. In: Disorders specifically related to pre-term birth. Rudolph C.D., Rudolph A.M., Lister G.E., First L.R., Gershon A.A., editors. Rudolph's Pediatrics ed. McGraw Hill Medical; New York: 2011. pp. 233–263. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guías de Práctica Clínica en el SNS. Ed. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; Madrid: 2014. Guía de Práctica Clínica de atención en el embarazo y el puerperio. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament de Salut . Direcció General de Salut Pública; Barcelona: 2005. Protocol de seguiment de l’embaraç a Catalunya, 2ª ed. Revisada. Available from: http://salutweb.gencat.cat/web/.content/home/ambits_tematics/linies_dactuacio/model_assistencial/ordenacio_cartera_i_serveis_sanitaris/pla_estrategic_dordenacio_maternoinfantil_i_atencio_salut_sexual_i_reproductiva/material_de_suport/documents/protsegui2006.pdf [accessed 13.04.17] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galbally M., Snellen M., Power J. Antipsychotic drugs in pregnancy: a review of their maternal and fetal effects. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5:100–109. doi: 10.1177/2042098614522682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goel N., Beasley D., Rajkumar V., Banerjee S. Perinatal outcome of illicit substance use in pregnancy-comparative and contemporary socio-clinical profile in the UK. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:199–205. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wadhwa P.D., Entringer S., Buss C., Lu M.C. The contribution of maternal stress to pre-term birth: issues and considerations. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:351–384. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loomans E.M., van Dijk A.E., Vrijkotte T.G., van Eijsden M., Stronks K., Gemke R.J. Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is related to adverse birth outcomes: results from a large multi-ethnic community-based birth cohort. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:485–491. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolibar B., Fina Avilés F., Morros R., Garcia-Gil M., del M., Hermosilla E., Grupo SIDIAP Base de datos SIDIAP: la historia clínica informatizada de Atención Primaria como fuente de información para la investigación epidemiológica. Med Clin. 2012;138:617–621. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institut d’Estadística oficial de Catalunya – IDESCAT Available from: https://www.idescat.cat/tema/naixe [accessed 13.04.17].

- 20.Domínguez-Berjón M.F., Borrell C., Cano-Serral G., Esnaola S., Nolasco A., Pasarín M.I. Construcción de un índice de privación a partir de datos censales en grandes ciudades españolas: (Proyecto MEDEA) Gac Sanit. 2008;22:179–187. doi: 10.1157/13123961. Available from: http://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-gaceta-sanitaria-138-articulo-construccion-un-indice-privacion-partir-S0213911108712329?referer=buscador [accessed 13.04.17]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norwegian Institute of Public Health; 2016. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. “ATC/DDD Index”. Available from: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ [accessed 13.04.17] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Männistö T., Mendola P., Kiely M., O’Loughlin J., Werder E., Chen Z. Maternal psychiatric disorders and risk of pre-term birth. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grigoriadis S., VorderPorten E.H., Mamisashvili L., Tomlinson G., Dennis C.L., Koren G. The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:e321–e341. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grote N.K., Bridge J.A., Gavin A.R., Melville J.L., Iyengar S., Katon W.J. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk od pre-term birth, low birth weight and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012–1024. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders Global Health Estimates. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254610/1/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf [accessed 13.04.17] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lilliecreutz C., Larén J., Sydsjö G., Josefsson A. Effect of maternal stress during pregnancy on the risk for pre-term birth. BioMed Central Preg Child. 2016;16:5. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0775-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang H., Coleman S., Bridge J.A., Yonkers K., Katon W. A meta-analysis of the relationship between antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of pre-term birth and low birth weight. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eke A.C., Saccone G., Berghella V. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and risk of pre-term birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Obst Gynaecol. 2016;123:1900–1907. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viktorin A., Lichtenstein P., Lundholm C., Almqvist C., D’Onofrio B.M., Larsson H. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor use during pregnancy: association with offspring birth size and gestational age. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:170–177. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sujan A.C., Rickert M.E., Öberg A.S., Quinn P.D., Hernández-Diaz S., Almqvist C. Associations of maternal antidepressant use during the first trimester of pregnancy with pre-term birth, small for gestational age, autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. J Am Med Assoc. 2017;317:1553–1562. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howard L.M., Molyneaux E., Dennis C.L., Rochat T., Stein A., Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014;384:1775–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Editorial Screening for perinatal depression: a missed opportunity. Lancet. 2016;387:505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.