Abstract

Introduction:

The American Psychiatric Association included Internet gaming disorder (IGD) in the 5th Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and the World Health Organization included gaming disorder in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases. These recent updates suggest significant concern related to the harms of excessive gaming.

Areas Covered:

This systematic review provides an updated summary of the scientific literature on treatments for IGD. Inclusion criteria were that studies: 1) evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention for IGD or excessive gaming; 2) use an experimental design (i.e., multi-armed [randomized or non-randomized] or pretest-posttest); 3) include at least 10 participants per group; and 4) include an outcome measure of IGD symptoms or gaming duration. The review identified 22 studies evaluating treatments for IGD: 8 evaluating medication, 7 evaluating cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, and 7 evaluating other interventions and psychosocial treatments.

Expert Opinion:

Even with the recent uptick in publication of such clinical trials, methodological flaws prevent strong conclusions about the efficacy of any treatment for IGD. Additional well-designed clinical trials using common metrics for assessing IGD symptoms are needed to advance the field.

Keywords: Internet gaming disorder, treatment, systematic review, video game addiction, excessive gaming

1. Introduction

Gaming is a popular form of entertainment, with 43% of adults and 90% of teenagers in the United States reporting playing video games1. A small subset of individuals who play video games are at risk for developing problems such as a preoccupation with gaming, withdrawal and tolerance symptoms, and a loss of interest in other activities. Both the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have recognized problems related to video games as a potentially diagnosable mental disorder. These classifications have not been without controversy, with some researchers arguing that inclusion of this diagnosis is premature2, 3.The APA included Internet gaming disorder (IGD) in the research appendix of the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)4, as an early formal effort to consolidate proposed disorder criteria while encouraging additional study into what criteria best describes the disorder. Informed by a large recent influx of research on Internet gaming disorder, the WHO organized a series of expert meetings to better understand gaming. Upon consideration of the important clinical and public health impact of gaming5, the WHO included it as a diagnosis in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11)6, but adopted a different name for this phenomenon (i.e., gaming disorder). Both ICD-11 and the DSM-5 specify that, to qualify for the diagnosis, symptoms must result in significant impairment. Of note, despite the differences in nomenclature, both definitions include video games played either on or off-line.

Research on prevalence rates and risk factors for IGD has uncovered inconsistent results, partially due to a lack of consensus on the definition of IGD prior to inclusion in the DSM-5. For example, a recent review found that prevalence estimates ranged from 0.7% to 27.5% internationally7. These substantial discrepancies may be due to actual cross-cultural differences in prevalence rates but are likely at least in part due to methodological differences between studies, including definitions of IGD, assessment instruments, and sampling. These methodological differences may also explain inconsistencies in the literature on risk factors for IGD. However, one consistent risk factor across studies and assessment methods for IGD is male gender8,9.

The last decade has seen a dramatic uptick of interest in treatment approaches for individuals with excessive video game use. This research attention is likely driven by the treatment need identified by parents of children with gaming problems, adults with gaming problems, as well as treatment providers who are seeing problems related to excessive gaming among their patient populations. Several papers have reviewed the literature on treatments for IGD10, 11, 12, 13, generally finding only weak research support for any one treatment approach. However, a substantial number of new treatment studies have been published in the past two years, warranting an updated review of the literature. Thus, this systematic review aims to provide a timely summary of the current state of the science on evidence-based treatments for IGD. Specifically, we will examine evidence for treatment efficacy of specific interventions for IGD, including the rigor of the research used to evaluate such treatments. Results will allow us to summarize strengths and weaknesses in the study design of the studies reviewed as well as identify gaps in the research literature that can inform the direction of future research efforts.

2. Method

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were that studies: 1) evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention for IGD or problems related to excessive gaming; 2) use a design that is either multi-armed (randomized or non-randomized) or pretest-posttest; 3) include at least 10 participants per group to exclude very small pilot studies and single case designs; and 4) include an outcome measure related to IGD symptoms or duration of gaming. Studies were excluded if they: 1) focused on prevention rather than treatment; 2) were review or theoretical papers; or 3) were not available in English. The database search was conducted on August 7, 2019.

2.2. Search strategy

We searched PubMed using the following combination of search terms specified for “All Fields”: [‘Internet gaming’ OR ‘gaming’ OR ‘video game’ OR ‘online gaming’ OR ‘digital gaming’ OR ‘game’] AND [‘addiction’ OR ‘pathological’ OR ‘excessive’ OR ‘problem’ OR ‘disorder’] AND [‘treatment’ OR ‘intervention’]. Secondary reference searching was conducted on all included studies.

2.3. Screening abstracts

Titles, abstracts, citation information, and descriptor terms of citations identified through the search strategy were screened in a two-step process. First, the first author conducted an initial screening to remove clearly non-relevant records. Full text articles were obtained for all records that remained after the initial review. Second, two research team members screened records independently and compared results. A third reviewer resolved all discrepancies.

2.4. Data extraction and management

For studies that met inclusion criteria, data were extracted by a trained coder and cross-checked by a second coder, with a third coder addressing differences. The following data points were collected from each study: type of treatment, sample size, mean age of the sample and standard deviation (or range when mean was not available), study design, nature of the comparison groups (when applicable), method of diagnosing IGD related to inclusion criteria (specific measure and type of measure), primary outcome variables related to IGD or gaming behavior, and study findings. Study findings were recorded for the primary outcome variables related to IGD (i.e., severity of IGD symptoms, time spent gaming). When a study included follow-up assessments past the immediate post-treatment assessment, results from both the post-treatment assessment and the longest follow-up are presented.

3. Results

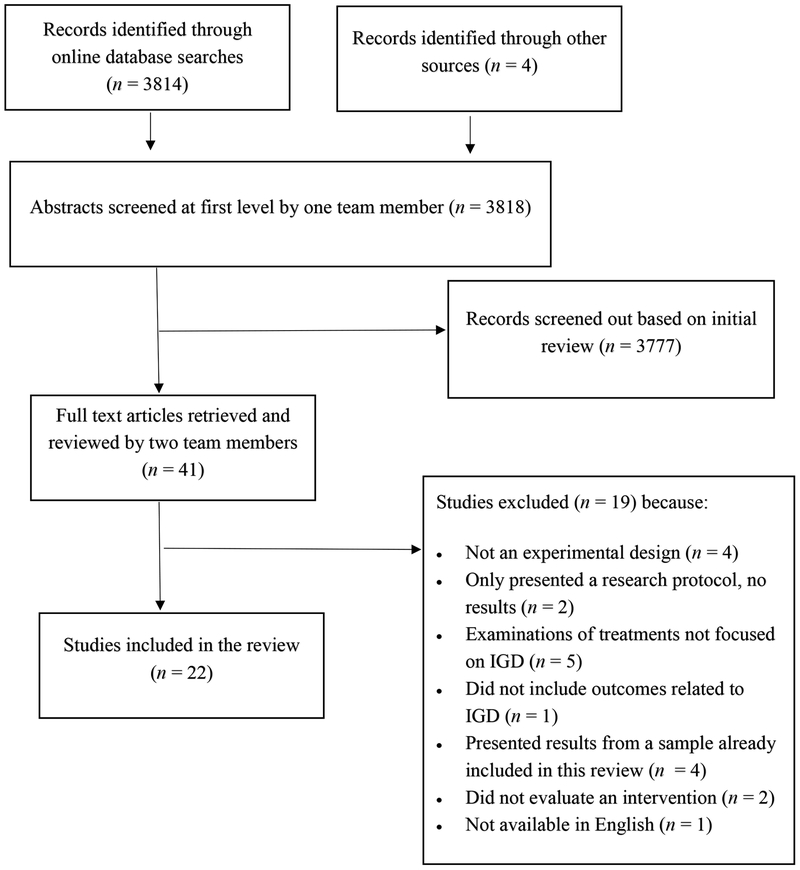

The initial database search yielded 3814 records; 4 additional records were identified through other means (see Figure 1). After records underwent initial screening, 41 were retained and underwent full-text review by two reviewers. Seven of the 41 (17.1%) required a third reviewer to resolve discrepancies.

Figure 1.

Disposition of study records

Of the 41 retained studies, 19 did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria based on full-text review: 2 only presented a research protocol and not results, 4 were not experimental designs (e.g., cohort studies), 5 did not evaluate a treatment specifically for IGD, 4 presented results from samples already presented in other papers included in this review, 1 did not present results related to gaming, 2 did not evaluate an intervention, and 1 was not available in English. The remaining 22 studies were included in this review.

3.1. Included studies

The final set of included studies is shown in Table 1, organized by type of treatment (medication, cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT], other treatment approaches) and then further organized by study design (first pretest-posttest designs, then other quasi-experimental designs, then randomized controlled trials). Seven studies evaluated medication treatments, 8 evaluated CBT-based therapies, and 7 evaluated other approaches. All studies focused on adolescent or young adult samples, with the exception of one medication trial that recruited children with a mean age of 9.3 years14. Two of the 7 medication studies, 4 of 8 CBT studies, and 1 of 7 studies of other approaches used a randomized controlled trial design. The remaining studies were primarily pretest-posttest designs or non-randomized controlled trials (i.e., included a control group but condition was not randomly assigned). Two of the medication trials employed random assignment to conditions, but no control group was included15, 16. There was substantial variability in the types of control groups employed in the psychosocial treatment studies, ranging from no treatment17 to active treatments18, 19. In terms of assessment of treatment outcome, twelve of the 22 studies used the Young Internet Addiction Scale (YIAS) to assess IGD, and the remaining studies used other self-reports or interviews.

Table 1.

Studies included in the final review.

| First author, year | Country | Treatments | N | Treatment duration (sessions) | Age M(SD) or range | Study Design | Assessment of IGD Inclusion Criteria; Type of Measure | Primary Outcome Variable(s) | Significant Results (follow-up timeframe) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication | |||||||||

| Bae, 201821 | South Korea | Bupropion | 15 | 12wks | 25.3±5.2 | Pre-post*~ | DSM-5 criteria; measure based on SCID-I; diagnostic interview | IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Decrease in YIAS (post-treatment) |

| Han, 201020 | South Korea | Bupropion | 11 | 6wks | 21.5±5.6 | Pre-post* | YIAS>50 + gaming >30 hr/wk + distress or impairment ; self-report | Weekly gaming (hrs); IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Decrease in gaming time and YIAS (post-treatment) |

| Han, 200914 | South Korea | Methylphenidate |

62 |

8wks |

9.3±2.2 |

Pre-post** | Video game playing was the only criteria; self-report | Weekly gaming (hrs); IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Decrease in gaming time and YIAS (post-treatment) |

| Nam, 201715 | South Korea | Bupropion Escitalopram |

15 15 |

12wks 12wks |

22.9±1.9 23.9±1.6 |

RT, no control group** | YIAS>50 + gaming > 4hrs/day or 30hrs/wk + distress or impairment; self-report | IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Decreased YIAS in both groups; no significant differences between groups (post-treatment) |

| Park, 2016a16 | South Korea | Atomoxetine Methylphenidate |

42 44 |

12wks 12wks |

17.1±1.0 16.9±1.6 |

RT, no control group** | DSM-5 criteria; specific measure not specified | IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Decreased YIAS in both groups but a test statistic for pre-post changes was not presented; no significant differences between groups (post-treatment) |

| Han, 2012b22 | South Korea | Bupropion+education Placebo+education |

25 25 |

8wks 8wks |

21.2±8.0 19.1±6.2 |

RCT*** | YIAS>50 + gaming >30 hrs/wk + distress or impairment; self-report | Weekly gaming (hrs); IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Greater reductions in gaming time and YIAS in the bupropion compared to placebo group (post-treatment) Reductions and group differences maintained at follow-up (4 wks post-treatment) |

| Song, 201623 | South Korea | Bupropion Escitalopram No Treatment Control |

44 42 33 |

6wks 6wks 6wks |

20.0±3.6 19.8±4.2 19.6±4.0 |

RCT† | DSM-5 criteria, no specific measure identified; diagnosed by a psychiatrist | IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Decreased YIAS for active groups, but not control. Greater decrease for bupropion than escitalopram (post-treatment) |

| CBT-based Psychotherapy | |||||||||

| Yao, 201725 | China | Group Reality & Mindfulness Therapy | 25 | 6wks (6) | 22.2±1.6 | Pre-post* | At least 5 DSM-5 criteria + ≥14 hr/wk of gaming + gaming was primary Internet activity; diagnostic interview | IGD symptoms (CIAS) | Decrease in CIAS (post-treatment) |

| González-Bueso, 201818 | Spain | Individual CBT Individual CBT + Parent Psychoed |

15 15 |

(12) (12 ind + 6 parent) |

15.5(2.3) 16.1(2.2) |

Non-RCT* | DQVMIA and SCID-I adapted to assess IGD; self-report and diagnostic interview | IGD symptoms (DQVMIA) | Decreased DQVMIA in both groups; no significant differences between groups (post-treatment) |

| Torres-Rodríguez, 201819 | Spain | Specialized CBT Standard CBT |

17 17 |

6mnth (22) 6mnth (22) |

15.1(1.9) 14.7(1.6) |

Non-RCT | 5 or more DSM-5 symptoms and IGD-20 score≥71; self-report and diagnostic interview | Weekly gaming (hrs); IGD symptoms (IGD-20) | Fewer hours of gaming and IGD symptoms in treatment vs control group (post-treatment). Differences were sustained but no between group comparison was presented (3 month follow-up) |

| Zhang, 2016b17†† | China | Craving behavioral intervention group No intervention control |

23 17 |

6wks(6) N/A |

21.9±1.8 22.0±1.9 |

Non-RCT | CIAS ≥67 + gaming >14hr/wk for ≥1yr; plays 1 of 4 most popular game^; self-report | Weekly gaming (hrs); IGD symptoms (CIAS) | Lower CIAS and less gaming in intervention group than controls (post-treatment) |

| Li et al., 201326 | China | CBT group therapy Basic counseling |

14 14 |

6wks(12) 6wks(12) |

12-19 yrs |

RCT | Gaming >30hr/wk + OGCAS >35 + IAS >3 + distress or maladaptive behavior; self-report and diagnosed by a psychiatrist | IGD symptoms (YIAS) | YIAS decreased in both groups but no group differences (post-treatment) |

| Li, 201724††† | USA | Mindfulness-oriented group therapy Support group |

15 15 |

8 wks(8) 8 wks(8) |

22.2(3.8) 27.8(5.5) |

RCT | At least subthreshold IGD (≥3 DSM-5 symptoms [yes/no questions]); self-report | Checklist based on DSM-5 IGD criteria (yes/no questions) | Greater reduction in IGD symptoms in treatment vs support group (3 month post-treatment) |

| Kim, 201227 | South Korea | CBT+ Bupropion Bupropion only |

32 33 |

8wks(8) 8wks |

16.2±1.4 15.9±1.6 |

RCT*** | YIAS>50 + gaming >30hr/wk + maladaptive treatment or distress; self-report |

Weekly gaming time; IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Greater reductions in gaming time and YIAS for CBT+med than med only group (post-treatment) Group differences maintained at follow-up (4 wks post-treatment) |

| Park, 2016b28 | South Korea | CBT group therapy Virtual Reality group therapy |

12 12 |

4wks(8) 4wks(8) |

24.2±3.2 23.6±2.7 |

RCT* | Gaming >30hr/wk + disruption of life + distress or maladaptive treatment + YIAS>50; self-report | IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Both groups had reductions in YIAS but no between group differences (post-treatment) |

| Other Interventions | |||||||||

| Han, 2012a29 | South Korea | Family therapy | 15 | 3 wks(5) | 14.2±1.5 | Pre-post* | Gaming >4hrs/day and >30hrs/wk + YIAS>50 + impaired treatment or distress; self-report |

Weekly gaming (hrs); IGD symptoms (YIAS) | Decrease in gaming time and YIAS score (post-treatment) |

| King, 201730 | Australia | Brief voluntary abstinence | 24 | 84 hours | 24.6(5.1) | Pre-post | Current MMO player; only n=9 met criteria for IGD; self-report | IGD symptoms (IGD checklist); Weekly gaming (hrs) | Decrease between baseline and 28 day follow-up in IGD checklist for the entire sample (the 9 participants who met IGD criteria had greater declines in symptoms than non-IGD participants). No decrease in gaming time for the entire group (28 day follow-up) but meeting IGD criteria predicted greater decreases in gaming time. |

| Lee, 201831 | South Korea | Transcranial direct current stimulation | 15 | 4 wks(12) | 21.3±1.4 | Pre-post* | Two or more IGD symptoms or plays games an average of 1 hr/day or more; self-report | IGD symptoms (YIAS); Weekly gaming (hrs) | Decrease in YIAS and weekly gaming (post-treatment) |

| Palleson, 201532 | Norway | Eclectic psychotherapy (CBT, family, motivational interviewing, solution-focused) | 12 | (13) | 15.7(1.3) | Pre-post | GASA ≥3 on all items and/or PVP score of 4 or 5 on all items; self-(GASA) and parent- (PVP) report | IGD symptoms (self-reported GASA and PVP, parent-reported PVP) | Decrease in parent-reported PVP but not self-reported GASA or PVP (post-treatment) |

| Sakuma, 201733 | Japan | Self-Discovery Camp | 10 | 9 days | 16.2±2.2 | Pre-post | Satisfied Griffith’s 6 components of addiction^^ + met DSM-V IGD criteria; diagnostic interview | Daily gaming (hours) and weekly gaming (hours and days) | Decrease in hours/day and hours/week of gaming but not days/week (3 months post-treatment) |

| Pornnoppoadol, 201834 | Thailand | Residential Camp (RC) Parent management (PM) RC + PM Psychoed |

24 24 26 30 |

7 days (8) 7 days + 8 PM sessions 1 hour |

14.6(1.4) 14.5(1.1) 14.0(1.4) 14.3(1.2) |

Non-RCT |

GAST-Parent version meeting the cut-off score; parent report | IGD symptoms (GAST-parent report) | Decrease in GAST in all four groups. All three active treatment groups superior to control at post-treatment and 6-month post-treatment. |

| Kim, 201335 | South Korea | MMORPG speaking and writing course General education |

27 32 |

8wks(21) 8wks(21) |

17.4±0.6 17.5±0.6 |

RCT | Playing DF ≥4hr/day; self-report | Average daily gaming in the past month (minutes) | Both groups showed reductions in gaming but no difference between groups (post-treatment) |

Note. CBT = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; CIAS = Chen Internet Addiction Scale; DF = Dungeon & Fighter; DQVMIA = Diagnostic Questionnaire for Video Games, Mobile Phone or Internet Addiction; GASA = Gaming Addiction Scale for Adolescents; GAST = Gaming Addiction Screening Test; IAS = Internet Addiction Scale; MMORPG = Massive Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games; OGCAS = Online Game Cognitive Addiction Scale; PM = Parent Management; PVP = Problem Video Game Playing Scale; RCT = randomized control trial; RT = randomized trial; SCID-I = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; YIAS = Young Internet Addiction Scale.

a sample of healthy controls was recruited by not included in primary analyses of interest;

all participants had a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder;

all participants had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder;

a sample of patients with Internet-based gambling disorder was recruited but not reviewed here;

participants were randomly assigned to the two medication groups but the control group were participants who declined medication treatment (not randomly assigned).

similar results were presented in three other publications by the same authors42, 43, 44; the paper that presented on the largest sample size was chosen for inclusion.

similar results were presented in a more recent publication not included here45.

participants reported playing one of the following games as their primary online activity: 1) Cross Fire; 2) Defense of the Ancient version 1; 3) Defense of the Ancient version 2; or 4) World of Warcraft.

Griffith’s six components of addiction are salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse46.

3.2. Medications

Medication trials examined drugs that are typically used to treat either depression (bupropion, escitalopram) or ADHD (methylphenidate, atomoxetine). Three studies used a pretest-posttest design, finding decreased IGD symptoms in response to 6-week20 and 12-week21 courses of bupropion and an 8-week course of methylphenidate14.

Two studies presented head to head comparisons of two different drugs. One compared 12 week courses of bupropion and escitalopram15, and the other compared 12 week courses of atomoxetine and methylphenidate16. Neither study had a placebo control group. The two studies had similar findings with decreases in IGD symptoms in response to both medications but no significant differences between the efficacy of the two drugs.

Two medication studies used randomized designs with control groups. The first found that an 8 week course of bupropion was superior to placebo in terms of reducing gaming time and IGD symptoms22. The second found that 6 week courses of either bupropion or escitalopram were superior to a no treatment control group in treatment of IGD symptoms and that this decrease was greater for bupropion than for escitalopram23.

3.3. CBT-based Psychotherapy

All of the treatments in this group utilized CBT principles but there was variability in the type of CBT, with some primarily using mindfulness strategies24, 25, others using gaming-specific CBT19 or CBT focused on craving17, and still others using standard CBT18, 26, 27, 28.

One study used a pre-post design to examine the effects of a 6 week group reality and mindfulness-based treatment, finding significant decreases in IGD symptoms25. Three additional studies used a non-randomized controlled trial, meaning that participants were non-randomly assigned to different treatment conditions. The first examined whether adding a parent psychoeducation component increased the effectiveness of individual CBT alone for adolescents with IGD18. Both groups (CBT alone and CBT plus parenting psychoeducation) showed significant decreases in IGD symptoms but adding the parenting component did not improve efficacy. The second compared specialized CBT for IGD to standard CBT for an adolescent sample19. Both groups showed significant decreases in gaming time and IGD symptoms at post-treatment, and the specialized CBT was superior to standard CBT. Further, both groups maintained their improvements at a 3-month follow-up. Finally, Zhang et al.17 compared a 6 week craving behavioral intervention group to a no intervention control in a young adult sample. They found lower levels of gaming time and IGD symptoms in the intervention group compared to the control group at post-treatment.

Four of the studies of CBT interventions were randomized controlled trials. The first compared a 6 week CBT group therapy to 6 weeks of basic counseling for adolescents and found no significant differences between groups26. The second found an 8-week mindfulness oriented group therapy to be superior to a support group in reducing IGD symptoms at 3 months post-treatment for a young adult sample24. Kim et al.27 found that the addition of CBT improved the effects of bupropion alone on both gaming time and IGD symptoms at 4 weeks post-treatment in a sample of adolescents. Finally, Park et al.28 compared 4 weeks of CBT group therapy to the same length of virtual reality group therapy and failed to find significant between group differences.

3.4. Other treatment approaches

The final seven studies examined an array of intervention approaches that did not fit into either the medication or CBT categories. The majority of these (n = 5) utilized pre-post designs. Han et al.29 found that five sessions of family therapy over three weeks was related to decreased gaming time and IGD symptoms. King et al.30 examined the effects of brief (i.e., 84 hours) voluntary abstinence. They recruited 24 participants but only 9 met full IGD criteria. The study did not find a significant improvement in gaming time for the entire sample, but the 9 participants who met IGD criteria did show a significant decrease. In addition, the entire sample showed a significant pre-post decrease in IGD symptoms. Lee et al.31 found that 12 sessions of transcranial direct current stimulation administered over 4 weeks was related to significant decreases in gaming hours and IGD symptoms among young adults. Palleson et al.32 examined 13 sessions of an eclectic treatment approach encompassing CBT, family therapy, motivational interviewing, and solution-focused therapy for adolescents, finding a significant improvement in parent-reported but not adolescent-reported IGD symptoms. The final pretest-posttest study found that a 9 day self-discovery camp was associated with a decrease in two of three measures of time spent gaming (i.e., hours per day and hours per week but not days per week) in an adolescent sample33.

Two studies of other treatment approaches included control groups. The first used a non-randomized design where participants chose one of four conditions: 1) 7-day residential camp; 2) 8 sessions of parent management; 3) residential camp and parent management or 4) psychoeducation34. All three active groups (1-3) were superior to the psychoeducation group on IGD symptoms at post-treatment and 6-month follow-up. Finally, a randomized controlled trial found that an 8 week speaking and writing course focused on massive multiplayer online role playing games was not superior to a general education control in reducing time spent gaming among adolescents35.

3.5. Expert opinion

This systematic review provides an updated summary of the state of the field, with 9 additional clinical trials published since the most recent comprehensive review13. Unfortunately, despite this relatively rapid uptick in research on treatments for IGD, none of the treatment approaches reviewed here have been studied with enough rigor to establish efficacy.

For medication treatments, only two studies used a randomized controlled trial22, 23; the first study showed initial evidence of efficacy for bupropion, but the sample was small (25 participants per group) and the treatment duration was only 8 weeks22. The second had a slightly larger sample size (33-44 participants per group) and found that bupropion was more efficacious than either escitalopram or a no treatment control23. None of the other medication trials included a control group, which precludes conclusions about treatment efficacy. Although bupropion shows initial evidence of efficacy, additional well-designed medication trials for IGD are needed; such trials can answer questions not only about direct effects of medication on IGD symptoms but can also shed light on the functional relationships between IGD and common comorbid conditions, including ADHD and depression.

CBT-based psychotherapy has been the most widely studied psychosocial treatment for IGD thus far, with four published randomized controlled trials of such treatments. Only two of these trials found that the CBT approach was superior to the control. One found that a mindfulness-oriented group treatment was superior to a support group and that this advantage was still present at 3 months post-treatment24. The other found that CBT plus bupropion was superior to bupropion alone (no psychotherapy) and these differences persisted through the 4 week follow-up27. Both studies had relatively small sample sizes but suggest that additional trials with larger samples are warranted. The other two randomized controlled trials failed to find an advantage of CBT over control, but this could be due to the short duration of treatments (6 weeks26 and 4 weeks28) or perhaps because the control groups were therapeutically active treatments (i.e., basic addictions counseling26; virtual reality group therapy28). Thus, although the initial research on CBT for IGD is promising, additional well-designed studies are needed to establish it as an evidence-based approach.

The other interventions identified by this review represent an eclectic and innovative array of approaches to IGD treatment, ranging from family therapy to residential treatment and transcranial stimulation. The majority of these have not been evaluated by rigorously designed studies, but pilot studies suggest that additional study may be warranted.

A central problem with the evaluation of IGD treatments is that the field has not yet established a common set of assessments of IGD symptoms. The YIAS is the most commonly used measure, with 12 of the studies described in this review utilizing this self-report to evaluate treatment outcomes. Although the common use of the YIAS aids in comparisons across studies, this measure was designed and validated to measure Internet overuse more generally and items are not specific to IGD, nor do they directly map on to the criteria proposed by the APA or ICD-11. At least one study modified the language of the YIAS to reflect IGD symptoms, changing the word “Internet” to “online games”31, but this does not appear to be the case for the majority of studies, which means that treatment effects may not be specific to gaming behaviors. Some studies used DSM-5 criteria to assess inclusion criteria or treatment outcome 16, 18, 19, 21, 23, 24, 25, 30, 33 but the method of assessment varied across study and was often not well described. Further, many of the studies used self-report measures of IGD to assess inclusion criteria, and all studies used a self-report measure of the primary outcome variables. Self-reports are not adequate in assessing clinical diagnoses because they produce a high number of false positives36. Other studies simply used amount of gaming time as the inclusion criteria or outcome variable, which is an unreliable predictor of IGD symptoms37. Clearly, a well-validated diagnostic clinical interview for IGD is needed and, once developed, should serve as a common metric for assessing inclusion in clinical trials and response to IGD treatments.

Over half of the studies included in the review were conducted in South Korea and thus may not generalize to other cultures. Certainly different treatment approaches may be more or less acceptable across cultures. A much larger number of treatment studies would need to be conducted across countries in order to examine such cross-cultural differences. Further, it will be vital to establish assessment approaches that have cross-cultural validity to aid in such comparisons.

The results of this systematic review should be considered in light of several limitations. First, only published studies were included in this review, which introduces the possibility of publication bias (i.e., study findings are more likely to be published if they are positive). Second, studies were only included if they were available in English. Given the strong international interest in this topic, this may have excluded some key studies. Third, we opted not to conduct a meta-analysis due to the substantially different measurement approaches to primary outcomes across studies. As additional treatment studies are published for IGD, a meta-analysis of treatment effects may be warranted and would provide a more precise estimate of treatment efficacy.

The study of treatments for IGD is still in its infancy and, given that rigorous trials of new treatments can take many years to complete, it is unlikely that we will have well-validated treatment approaches in the next five years. Further, basic research on IGD is still needed. Controversy remains about whether IGD is even a distinct mental disorder and, if IGD is determined to be better explained by comorbid conditions, our approach to treatment of problems related to excessive gaming is likely to focus on effective treatments of these comorbidities. The IGD criteria proposed by the DSM-5 represented a consensus based on the available literature38. The understanding of IGD has been further refined by more recent expert WHO working groups to establish the ICD-11 definition of gaming disorder, but additional work in this area remains, including validating these proposed symptoms and clinical cutoffs and developing and validating assessment instruments. Another key research question pertains to the course of IGD. For example, we know little about whether problems related to excessive gaming are likely to remit over time without treatment and, if so, what predicts remission versus continued problems. Some initial studies suggest that excessive gaming may be transitory in nature for most adults without formal intervention39 while others find substantial stability in gaming problems over time40; this line of research has important implications for treatment development.

Ideally, the basic questions about IGD would be answered before moving on to treatment development and evaluation. However, individuals and families who are impacted by problems related to excessive gaming are seeking expert help, and providers have identified excessive gaming as a treatment need, as evidenced by treatment facilities and online support groups that have appeared in various markets internationally. Thus, it is not practical to delay treatment research until basic research is completed. Instead, researchers should focus their attention on conducting well-designed clinical trials of treatments that have shown either initial efficacy for IGD or that have shown promise in similar conditions (e.g., addictions). For example, given the high prevalence of gaming among adolescents and young adults, researchers could consider adapting treatments for youth substance use disorders. Many such treatments have a strong family component41; thus, it is surprising that only a few studies so far have evaluated IGD treatments that encourage family involvement29, 32, 34. In addition, adolescents presenting for treatment for IGD will likely have different clinical and developmental needs than young adults or older adults. This research area is clearly an avenue for continued exploration, and we recommend that researchers build upon our existing knowledge of other addictive behaviors in designing and evaluating treatments. Further, flaws in existing studies make it difficult to draw strong conclusions; future studies should ensure that participants are randomized to treatment conditions and that appropriate control groups are included to allow for more definitive conclusions about treatment efficacy.

In sum, research on IGD has increased exponentially over the past decade, particularly since the publication of the DSM-5. However, the field has a long way to go to establish an evidence base for IGD treatment. In the coming years, we can expect to see more nuanced research on best practices for how to assess IGD symptoms, the course of IGD over time, and an increase in well-designed clinical trials of IGD treatments.

Article highlights.

Video games use is common, and only a small minority of individuals who play video games develop significant problems related to overuse.

The American Psychiatric Association has included Internet gaming disorder (IGD) in the 5th Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), and the World Health Organization has included gaming disorder in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11).

Researchers, clinicians, and the public have shown an uptick in interest in treatment approaches for Internet gaming disorder, and this review summarizes clinical trials of IGD treatments.

A total of 22 studies of treatment approaches for IGD were included in this review with 7 evaluating medications, 8 evaluating cognitive-behavioral therapy, and 7 evaluating other non-medication approaches.

Research on medications for IGD is inconclusive. Bupropion shows some promise but remains in initial stages of evaluation.

Some studies on cognitive-behavioral therapy for IGD find it to be superior to control conditions but others do not. Additional research is needed on these approaches.

In general, weaknesses in the designs of the reviewed studies, including lack of appropriate control groups, non-random assignment to treatment conditions, and small sample sizes, prevent strong conclusions about the efficacy of treatments for IGD.

Well-designed and adequately powered clinical trials are needed to move the field forward. Researchers should consider adapted treatments known to be effective for other addictive behaviors, including substance use.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Preparation of this manuscript was supported, in part, by grants K23DA034879 and R21DA042900 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (*) or of considerable interest (**) to readers.

## denotes paper included in the systematic review

- 1.Duggan M (2015). Gaming and Gamers. Pew Research Center; Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/12/15/gaming-and-gamer [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarseth E, Bean AM, Boonen H, Colder Carras M, Coulson M, Das D, … & Haagsma MC (2017). Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 267–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Describes the concerns about inclusion of gaming disorder in the ICD-11 and argues that this decision will cause harm to gamers and will waste public health resources.

- 3.Bean AM, Nielsen RK, Van Rooij AJ, & Ferguson CJ (2017). Video game addiction: The push to pathologize video games. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48(5), 378–389. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rumpf HJ, Achab S, Billieux J, Bowden-Jones H, Carragher N, Demetrovics Z, … & Saunders JB (2018). Including gaming disorder in the ICD-11: The need to do so from a clinical and public health perspective: Commentary on: A weak scientific basis for gaming disorder: Let us err on the side of caution (van Rooij et al., 2018). Journal Of Behavioral Addictions, 7(3), 556–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. (2018). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th Revision). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

- 7.Mihara S, & Higuchi S (2017). Cross-sectional and longitudinal epidemiological studies of Internet gaming disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 71(7), 425–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Provides a systematic review of international prevalence rates of Internet gaming disorder, risk factors, and studies of the natural course of symptoms.

- 8.Desai RA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Cavallo D, & Potenza MN (2010). Video game playing in high school students: health correlates, gender differences and problematic gaming. Pediatrics, 126(6), e1414–e1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rehbein F, Kliem S, Baier D, Mößle T, & Petry NM (2015). Prevalence of Internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: Diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample. Addiction, 110(5), 842–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorgenson AG, Hsiao RC, & Yen CF (2016). Internet addiction and other behavioral addictions. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25, 509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King DL, & Delfabbro PH (2014). Internet Gaming Disorder treatment: A review of definitions of diagnosis and treatment outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(10), 942–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuss DJ, & Lopez-Fernandez O (2016). Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: A systematic review of clinical research. World Journal of Psychiatry, 6(1), 143–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *An earlier systematic review that reviews treatment for Internet addiction more broadly defined.

- 13.Zajac K, Ginley MK, Chang R & Petry NM (2017). Treatments for Internet gaming disorder and Internet addiction: A systematic review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 979–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Differentiates between Internet gaming disorder and Internet addiction and provides a systematic review of treatments for both.

- ##14.Han DH, Lee YS, Na C, Ahn JY, Chung US, Daniels MA, … & Renshaw PF (2009). The effect of methylphenidate on internet video game play in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50(3), 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##15.Nam B, Bae S, Kim SM, Hong JS, & Han DH (2017). Comparing the effects of bupropion and escitalopram on excessive internet game play in patients with major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 15(4), 361–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##16.Park JH, Lee YS, Sohn JH, & Han DH (2016a). Effectiveness of atomoxetine and methylphenidate for problematic online gaming in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Human Psychopharmacology, 31(6), 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##17.Zhang JT, Yao YW, Potenza MN, Xia CC, Lan J, Liu L, … & Fang XY (2016b). Effects of craving behavioral intervention on neural substrates of cue-induced craving in internet gaming disorder. NeuroImage:Clinical, 12, 591–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##18.Gonzalez-Bueso V, Santamaria JJ, Fernandez D, Merino L, Montero E, Jimenez-Murcia S, … & Ribas J (2018). Internet gaming disorder in adolescents: Personality, psychopathology, and evaluation of a psychological intervention combined with parent psychoeducation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##19.Torres-Rodríguez A, Griffiths MD, Carbonell X, & Oberst U (2018). Treatment efficacy of a specialized psychotherapy program for Internet Gaming Disorder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 939–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##20.Han DH, Hwang JW, & Renshaw PF (2010). Bupropion sustained release treatment decreases craving for video games and cue-induced brain activity in patients with internet video game addiction. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(4), 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##21.Bae S, Hong JS, Kim SM, & Han DH (2018). Bupropion shows different effects on brain functional connectivity in patients with Internet-based gambling disorder and Internet gaming disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##22.Han DH, & Renshaw PF (2012b). Bupropion in the treatment of problematic online game play in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 26(5), 689–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##23.Song J, Park JH, Han DH, Roh S, Son JH, Choi TY, … & Lee YS (2016). Comparative study of the effects of bupropion and escitalopram on internet gaming disorder. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 70(11), 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##24.Li W, Garland EL, McGovern P, O’Brien JE, Tronnier C, & Howard MO (2017). Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for internet gaming disorder in US adults: A stage I randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(4), 393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##25.Yao YW, Chen PR, Hare TA, Li S, Zhang JT, … & Fang XY (2017). Combined reality therapy and mindfulness meditation decrease intertemporal decisional impulsivity in young adults with Internet gaming disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- ##26.Li H,L, & Wang S (2013). The role of cognitive distortions in online game addiction among Chinese adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 1468–1475. [Google Scholar]

- ##27.Kim SM, Han DH, Lee YS, & Renshaw PF (2012). Combined cognitive behavioral therapy and bupropion for the treatment of problematic on-line game play in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1954–1959. [Google Scholar]

- ##28.Park SY, Kim SM, Roh S, Soh MA, Lee SH, Kim H, & Han DH (2016b). The effects of a virtual reality treatment program for online gaming addiction. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 129, 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##29.Han DH, Kim SM, Lee YS, & Renshaw PF (2012a). The effect of family therapy on the changes in the severity of on-line game play and brain activity in adolescents with on-line game addiction. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 202(2), 126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##30.King DL, Kaptsis D, Delfabbro PH, & Gradisar M (2017). Effectiveness of brief abstinence for modifying problematic internet gaming cognitions and behaviors. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(12), 1573–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##31.Lee SH, Im JJ, Oh JK, Choi EK, Yoon S, Bikson M, … & Chung YA (2018). Transcranial direct current stimulation for online gamers: A prospective single-arm feasibility study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 1166–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##32.Pallesen S, Lorvik IM, Bu EH, & Molde H (2015). An exploratory study investigating the effects of a treatment manual for video game addiction. Psychological Reports, 117(2), 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##33.Sakuma H, Mihara S, Nakayama H, Miura K, Kitayuguchi T, Maezono M, … & Higuchi S (2017). Treatment with the self-discovery camp (SDiC) improves internet gaming disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ##34.Pornnoppadol C, Ratta-apha W, Chanpen S, Wattananond S, Dumrongrungruang N, Thongchoi K, … & Vasupanrajit A (2018). A comparative study of psychosocial interventions for internet gaming disorder among adolescents aged 13–17 years. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- ##35.Kim PW, Kim SY, Shim M, Im C, & Shon Y (2013). The influence of an educational course on language expression and treatment of gaming addiction for massive multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) players. Computers & Education, 63, 208–217. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maraz A, Király O, & Demetrovics Z (2015). The diagnostic pitfalls of surveys: if you score positive on a test of addiction, you still have a good chance not to be addicted. A response to Billieux et al., 2015. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 151–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Király O, Tóth D, Urbán R, Demetrovics Z, & Maraz A (2017). Intense video gaming is not essentially problematic. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(7), 807–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petry NM, Rehbein F, Gentile DA, Lemmens JS, Rumpf HJ, Mößle T, … & Auriacombe M (2014). An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction, 109(9), 1399–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Describes the decision to include Internet gaming disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and presents the initial consensus on the nine DSM-5 criteria for IGD.

- 39.Konkolÿ Thege BK, Woodin EM, Hodgins DC, & Williams RJ (2015). Natural course of behavioral addictions: A 5-year longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Studies a large cohort of adults for 5 years and concludes that the majority of problematic gaming behaviors, as well as other excessive behaviors, are transitory in nature

- 40.Krossbakken E, Pallesen S, Mentzoni RA, King DL, Molde H, Finserås TR, & Torsheim T (2018). A cross-lagged study of developmental trajectories of video game engagement, addiction, and mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Followed a sample of adolescents over 3 years and found pathological gaming to be stable, with a low likely of spontaneously resolving.

- 41.Tanner-Smith EE, Wilson SJ, & Lipsey MW (2013). The comparative effectiveness of outpatient treatment for adolescent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44,145–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng LY, Liu L, Xia CC, Lan J, Zhang JT, & Fang XY (2017). Craving behavior intervention in ameliorating college students’ internet game disorder: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang JT, Yao YW, Potenza MN, Xia CC, Lan J, Liu L, … Fang XY (2016a). Altered resting-state neural activity and changes following a craving behavioral intervention for Internet gaming disorder. Scientific Reports, 6, 28109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang JT, Ma SS, Li CR, Liu L, Xia CC, Lan J, … Fang XY (2018). Craving behavioral intervention for internet gaming disorder: Remediation of functional connectivity of the ventral striatum. Addiction Biology, 23(1), 337–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li W, Garland EL, & Howard MO (2018). Therapeutic mechanisms of mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for internet gaming disorder: Reducing craving and addictive behavior by targeting cognitive processes. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffiths M (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar]