Abstract

A series of quinoline-chalcone hybrids was designed as potential anti-cancer agents, synthesized and evaluated. Different cytotoxic assays revealed that compounds experienced promising activity. Compounds 9i and 9j were the most potent against all the cell lines tested with IC50 = 1.91–5.29 μM against A549 and K-562 cells. Mechanistically, 9i and 9j induced G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in both A549 and K562 cells. Moreover, all PI3K isoforms were inhibited non selectively with IC50s of 52–473 nM when tested against the two mentioned compounds with 9i being most potent against PI3K-γ (IC50 = 52 nM). Docking of 9i and 9j showed a possible formation of H-bonding with essential valine residues in the active site of PI3K-γ isoform. Meanwhile, Western blotting analysis revealed that 9i and 9j inhibited the phosphorylation of PI3K, Akt, mTOR, as well as GSK-3β in both A549 and K562 cells, suggesting the correlation of blocking PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway with the above antitumor activities. Together, our findings support the antitumor potential of quinoline-chalcone derivatives for NSCLC and CML by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway.

Keywords: Cancer, Quinoline, Chalcone, G2/M arrest, Apoptosis, PI3K pathway

1. Introduction

Cancer constitutes a tremendous load on society in more and less economically developed countries alike [1]. In Egypt, age-standardized incidence rates of cancer per 100,000 were 166.6 (both sexes), 175.9 (males), and 157.0 (females). By 2050, a 3-fold increase in incidence cancer relative to 2013 was estimated in the Egyptian population, and includes lung and leukemia cancers [2]. Search for new anti-cancer agents have been always a challenging task for medicinal chemists to counter the spread of cancer in Egypt and throughout the world. Quinoline, a biologically important heterocycle, has been widely investigated as an important motif in the development of anti-cancer agents [3]. The mechanism of action of quinoline and its analogues includes inhibition of several cell growth promoting factors such as tyrosine kinases, proteasome, tubulin polymerization, topoisomerase and DNA repair [3]. Chalcone is another scaffold of significant importance in the discovery of anti-cancer agents [4]. Though not fully explored, proposed mechanisms for the cytotoxic activity of chalcone include induction of apoptosis, cell cycle disruption, inhibition of tubulin polymerization, blockade of nuclear factor-kappa B, and inhibition of certain kinases required for cell cancer survival and proliferation[4]. One pathway that was reported to be inhibited by both quinoline [5,6] and chalcone [7,8] scaffolds is PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. PI3K/AKT/mTOR cascade is one of the most important commonly activated pathways in lung cancer and leukemia [9,10]. The phosphoinositide 3 kinases (PI3Ks) constitute a family of lipid kinases, which includes PI3K1, PI3K2 and PI3K3 that phosphorylate the 3-hydroxy group of phosphoinositides. PI3K1 is the most well-characterized PI3Ks, which comprise a catalytic subunit (p110α, p110β, p110δ and p110γ) and a regulatory subunit (p85) [11]. Phosphorylation of PI3K is followed by phosphorylation of a series of subsequential effectors including protein kinase B (PKB/Akt), mTOR, and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) [12]. These effectors are linked to various cellular processes. They initiate a signaling cascade that is involved in several aspects of tumorigenesis including the inhibition of apoptosis, promotion of cell cycle, proliferation, and angiogenesis [13–18].

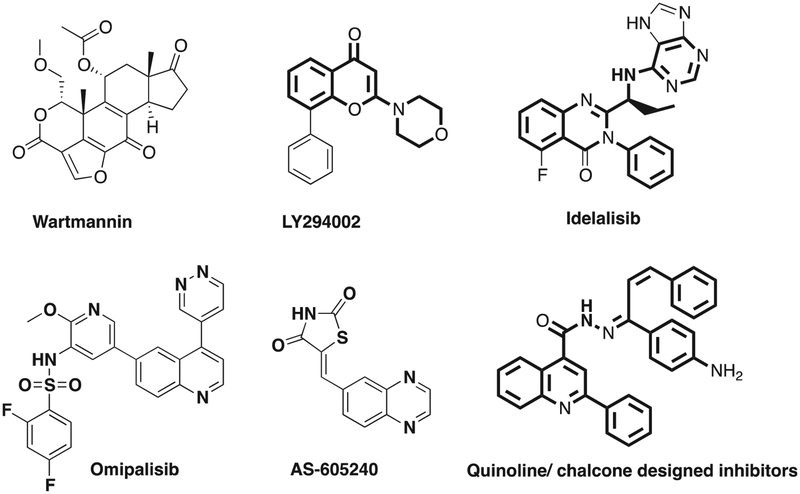

Wortmannin and LY294002 (Fig. 1) were first two PI3K inhibitors and developed in the 1990s. Subsequently a pool of PI3K inhibitors were developed and emerged as promising anti-cancer agents. Idelalisib (PI3Kδ inhibitor, Fig. 1) was FDA approved in July 2014 for treatment of leukemia and certain types of lymphoma [19]. Several trials to test new PI3K inhibitors are currently ongoing. However, the clinical use of PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors has been hampered by instability, hepatotoxicity, and low potency [20]. Thus, the search for new PI3k inhibitors remain. Previous reports implicate three essential pharmacophores in the design of a successful PI3K inhibitor: a hydrogen acceptor that binds with essential valines in the hinge region, a binder that fits into the affinity binding pocket, and a ribose pocket binder that occupies the ATP ribose binding pocket [21].

Fig. 1.

Structures of Wartmannin, LY294002, Idelalisib, Omilpalisib, AS-05240 and the designed inhibitors.

Omipalisib (GSK 2126458, Fig. 1) is a quinoline that is a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor by acting as a hinge binder to Val882 of PI3Kγ [22], and which is currently in Phase I clinical trials. Researchers later used quinoline as the foundation for the design of PI3K inhibitors based on GSK2126458 [23–25]. Chalcones were also designed as potent PI3K inhibitors based on its structure similarity with AS-605240 (Fig. 1) a safe and potent PI3Kγ inhibitor with anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory properties [26,27]. A growing number of studies has been directed towards quinoline and chalcone optimization and incorporation into chemotherapeutic agents [28–31]. The current research is directed towards further optimization of these two entities, and aimed at the discovery of more potent anticancer agents targeting PI3K pathway using quinoline and chalcone scaffolds (Fig. 1).

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

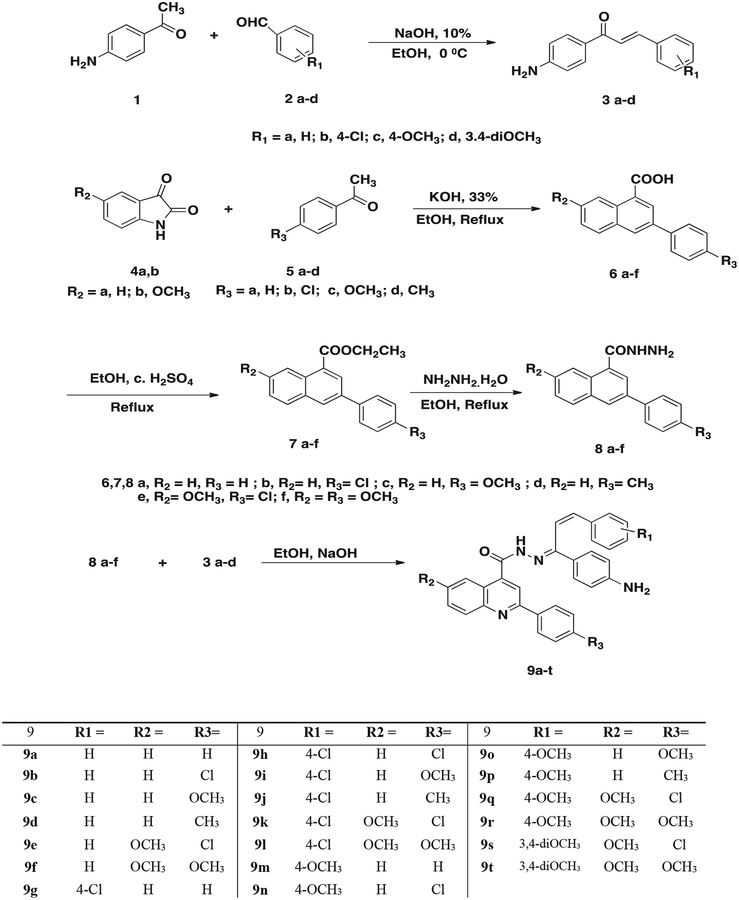

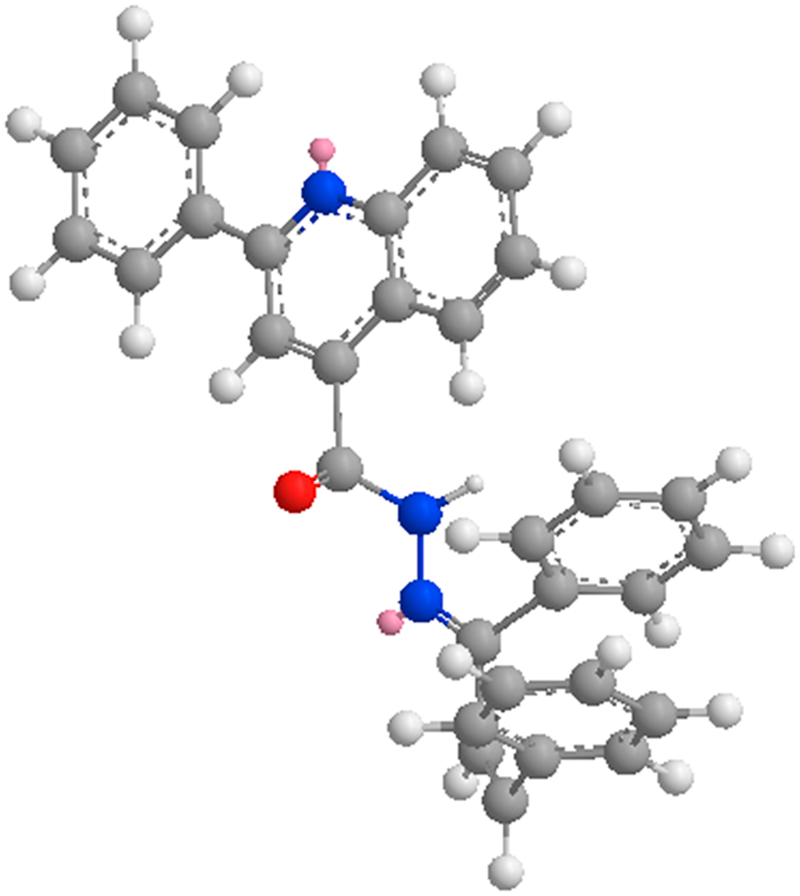

Synthesis of the designed quinolone/chalcones hybrids starts with reaction of various aromatic aldehydes 2a-d with p-aminoacetophenone through usual Clasien Schmidt condensation to form the corresponding chalcones 3a-d, Scheme 1. 2-Aryl-quinoline-4-carboxylic acids 6a-f were obtained via the reaction of Isatin with substituted acetophenones. The acids formed are converted to ethyl esters 7a-f via Fisher esterification using ethanol and conc. H2SO4. The obtained esters are then converted to the corresponding hydrazides 8a-f using hydrazine hydrate, Scheme 1. Coupling both chalcones 3a-d with the hydrazides 8a-f yielded the desired hydrazones 9a-t (Table 1). The appearance of 2 doublets for the 2 chalcone olefenic protons in the aromatic region along with one exchangeable proton at 12.09–12.31 ppm for NH in 1H NMR confirmed the formation of open hydrazone structure. No evidence of cyclization to pyrazoline was observed. The NMR data revealed that the 2 olefinic protons are present in a cis form. Coupling constants calculated from those protons were around 8 Hz, which excluded the possibility of having the trans isomer. Theoretical calculations using ChemBio Draw 14 revealed that the cisoid form has a total energy of 2.3 versus 7.9 Kcal/mol for the trans form. The stability of the cis isomer might be attributed to a π–π stacking interaction between the 2 parallel phenyl groups as demonstrated in Fig. 2. The presence of such geometry might also be responsible for the absence of the 2-pyrazoline cyclization usually observed in hydrazide-chalcone reactions.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of (E)-N’-((Z)-1-(4-aminophenyl)-3-phenylallylidene)-2-(phenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide derivatives 9a-t.

Table 1.

GI50 of compounds 9i and 9j against 59 cell lines in 9 different cancer panels tested using NCI’s in vitro five dose anticancer assay.

| Panel/cell line | GI50 Compound | Panel/cell line | GI50 Compound | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9i | 9j | 9i | 9j | ||

| Leukemia | Melanoma | ||||

| CCRF-CEM | 5.84 | 4.53 | LOX IMVI | 1.56 | 4.00 |

| HL-60(TB) | 2.54 | 3.49 | MALME-3M | > 100 | > 100 |

| K-562 | 1.05 | 3.09 | M14 | 1.16 | 2.54 |

| MOLT-4 | 3.30 | 3.23 | MDA-MB-435 | 0.305 | 1.00 |

| RPMI-8226 | 3.86 | 4.10 | SK-MEL-2 | 2.03 | 3.81 |

| SR | 0.595 | 3.29 | SK-MEL-28 | 3.78 | 6.23 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | SK-MEL-5 | 0.701 | 2.50 | ||

| A549/ATCC | 2.33 | 4.79 | UACC-257 | > 100 | 33.7 |

| EKVX | 3.78 | 3.99 | UACC-62 | 0.556 | 2.06 |

| HOP-62 | 3.21 | 4.62 | Ovarian cancer | ||

| HOP-92 | 1.92 | 4.10 | IGROV1 | 4.98 | 6.48 |

| NCI-H226 | 7.54 | 6.47 | OVCAR-3 | 0.462 | 2.98 |

| NCI-H23 | 3.14 | 5.02 | OVCAR-4 | 1.82 | 4.71 |

| NCI-H322M | 6.00 | 4.73 | OVCAR-5 | 5.51 | 8.43 |

| NCI-H460 | 1.89 | 3.51 | OVCAR-8 | 4.16 | 5.25 |

| NCI-H522 | 0.307 | 0.622 | NCI/ADR-RES | 0.519 | 2.54 |

| Colon cancer | SK-OV-3 | 3.32 | 4.94 | ||

| COLO 205 | 1.99 | 2.80 | Renal cancer | ||

| HCC-2998 | 3.40 | 4.28 | 786–0 | 1.84 | 4.22 |

| HCT-116 | 1.41 | 3.18 | A498 | 0.375 | 1.64 |

| HCT-15 | 1.03 | 3.33 | ACHN | 1.47 | 4.19 |

| HT29 | 1.13 | 3.35 | RXF 393 | 0.698 | 1.63 |

| KM12 | 1.15 | 3.46 | SN12C | 4.27 | 6.84 |

| SW-620 | 1.24 | 4.24 | TK-10 | 52.30 | 8.51 |

| CNS cancer | UO-31 | 1.55 | 2.20 | ||

| SF-268 | 2.19 | 4.09 | |||

| SF-295 | 0.540 | 3.13 | Breast cancer | ||

| SF-539 | 1.41 | 2.43 | MCF7 | 0.442 | 2.53 |

| SNB-19 | 5.54 | 6.51 | MDA-MB231/ATCC | 3.28 | 3.94 |

| SNB-75 | 0.371 | 1.41 | HS 578T | 1.05 | 4.68 |

| U251 | 2.18 | 4.51 | BT-549 | 2.04 | 3.92 |

| Prostate cancer | T-47D | 2.70 | 2.73 | ||

| PC-3 | 2.03 | 3.40 | MDA-MB-468 | 2.95 | 4.91 |

| DU-145 | 3.16 | 3.68 | |||

Fig. 2.

Possible stacking interaction for compound 9i.

2.2. Biological evaluation

2.2.1. Anti-cancer activity NCI screening

Compounds 9b-c, 9e, 9h-l, 9n-o, and 9r-s were selected by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), USA for in vitro anti-cancer screening. Compounds were initially screened at the 10 μM dose using a Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay and the NCI 60 cell lines derived from nine tumor subpanels, including leukemia, lung, colon, melanoma, renal, prostate, CNS, ovarian, and breast cancer cell lines.

Our results show promising anti-cancer activities against different human cancer cells of our compounds, with mean growth inhibition of 25.5–74% (Supporting information). Furthermore, compounds 9i and 9j (mean growth inhibition of 73.03 and 73.98%, respectively), were selected by the NCI for the five-dose assay (Table 1, Supporting information). Both compounds are potent cytotoxic agents with GI50s of 0.3–52 μM against most cells. Both non-small cell lung cancer and chronic myeloid leukemia were highly sensitive to both compounds, with GI50s of 0.3–6 μM (Table 1, Supporting information).

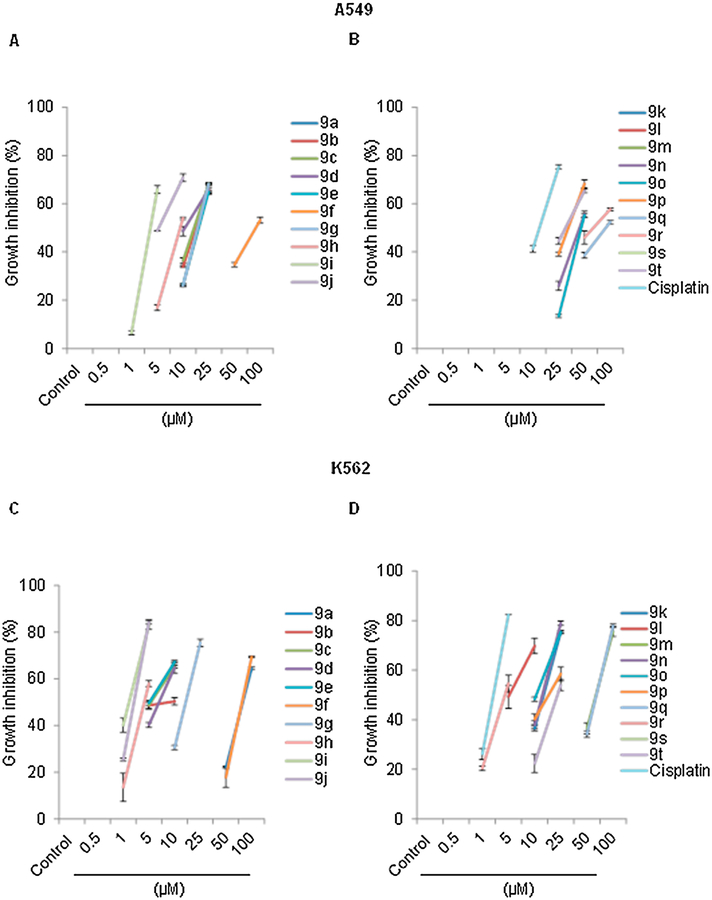

2.2.2. Anti-proliferative and cytotoxic activities on A549 and K-562 cell lines

To assess the anti-proliferative and the cytotoxic activities of compounds 9a-t on the A549 and K-562 cell lines, were assessed using BrdU incorporation and trypan blue exclusion assays, respectively. A549 and K-562 cells were treated with different concentrations (0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50 or 100 μM) of quinolone/chalcone hybrids 9a-t or the reference cisplatin for 24 h using DMSO as a negative control. Data were summarized in Table 2, Fig. 3 and Supporting information. Fifteen compounds out of twenty (9b-j, 9n-r and 9t) inhibited the growth and decreased the viability of A549 cells in a dose dependent manner (IC50 = 3.91–97.23 μM), while five compounds (9a, 9k-m, and 9s) have very weak or no anticancer activity (IC50 > 100 μM). Compounds 9d, 9h, 9i and 9j were more potent than cisplatin (IC50s = 11, 9, 4, and 5 μM for 9d, 9h, 9i and 9j respectively vs 15.3 μM for cisplatin, Table 2). The synthesized hybrids were more potent against the K-562 cell line, with nineteen compounds inhibiting growth and decreasing viability with IC50s = 1.91–82.84 μM. Compounds 9i and 9j were comparably potent as cisplatin, with IC50s of 1.9 and 2.7 μM respectively compared to 2.71 μM for cisplatin. Consistent with the NCI results, compounds 9i and 9j exhibited the highest activities against A549 cells (IC50 = 3.91 and 5.29 μM, respectively) and K-562 cells (IC50 = 1.91 and 2.67 μM, respectively).

Table 2.

Half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of quinoline chalcone hybrids 9a-t, cisplatin and LY294002 determined using human lung adenocarcinoma A549 and chronic myeloid leukemia K-562 cell lines and trypan blue exclusion assay.

| Compound | A549 (IC50 μM)a | K-562 (IC50 μM)a | Compound | A549 (IC50 μM)a | K-562 (IC50 μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9a | > 100 | 82.84 ± 3.24 | 9l | > 100 | 5.17 ± 0.18 |

| 9b | 17.56 ± 2.5 | 8.96 ± 1.06 | 9m | > 100 | 60.67 ± 2.67 |

| 9c | 16.43 ± 1.3 | 5.37 ± 0.31 | 9n | 48.32 ± 1.69 | 14.43 ± 0.94 |

| 9d | 11.21 ± 0.52 | 6.98 ± 0.92 | 9o | 46.51 ± 2.21 | 10.93 ± 0.74 |

| 9e | 19.2 ± 1.85 | 5.09 ± 0.19 | 9p | 33.91 ± 2.15 | 18.03 ± 0.97 |

| 9f | 91.39 ± 4.54 | 81.21 ± 3.14 | 9q | 97.23 ± 2.36 | 68.07 ± 2.87 |

| 9g | 18.54 ± 0.52 | 15.17 ± 2.15 | 9r | 67.37 ± 2.29 | 4.45 ± 0.64 |

| 9h | 9.46 ± 0.63 | 4.28 ± 0.34 | 9s | > 100 | > 100 |

| 9i | 3.91 ± 0.31 | 1.91 ± 0.21 | 9t | 31.6 ± 2.02 | 23.11 ± 2.15 |

| 9j | 5.29 ± 0.19 | 2.67 ± 0.27 | Cisplatin | 15.3 ± 1.87 | 2.71 ± 0.34 |

| 9k | > 100 | 15.22 ± 1.49 | LY294002 | 3.52 | 2.68 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD from the dose response curves of at least three independent experiments.

Fig. 3.

Growth inhibition % observed with different concentrations (0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 μM) of compounds and measured using BrdU incorporation assay. (A) A549 cells treated with 9a-j (B) A549 cells treated with 9h-t or cisplatin (C) K-562 cells treated with 9a-j (D) K-562 cells treated with 9h-t or cisplatin. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

A simple structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis revealed that the presence of electron withdrawing group (chloride) on ring A of the chalcone is predictive of their cytotoxic activity (IC50 of 1.9–18.5 μM for compounds 9g-j against the 2 cell lines tested). In this group of compounds, the activity is optimal when a electron donating group (OCH3, CH3) is present on the 2-phenyl ring on the quinoline moiety, and decreased with the presence of an electron withdrawing group or unsubstituted ring. Compound 9i has IC50s of 1.9 and 3.9 μM against K-562 and A549 cells, respectively while 9g has IC50s of 15.2 and 18.5 μM against K-562 and A549, respectively. In A549 cells, this activity is nearly abolished with the presence of an OCH3 group on the sixth position of the quinolone ring. The presence of an unsubstituted phenyl ring in compounds 9a-f, resulted in decreased activity (IC50s of 5.1–100 μM). The activity is also diminished with the presence of 6-OCH3 at the quinolone ring (IC50 of 91 and 81 μM for compound 9f against the 2 cell lines) and the absence of substitution at the 2-phenyl group (IC50s of > 100 and 83 μM for compound 9a against the 2 cell lines). The presence of either 4-OCH3 or 3,4-diOCH3 on ring A of chalcones in 9m-t decreased the activity.

2.2.3. Cell cycle analysis

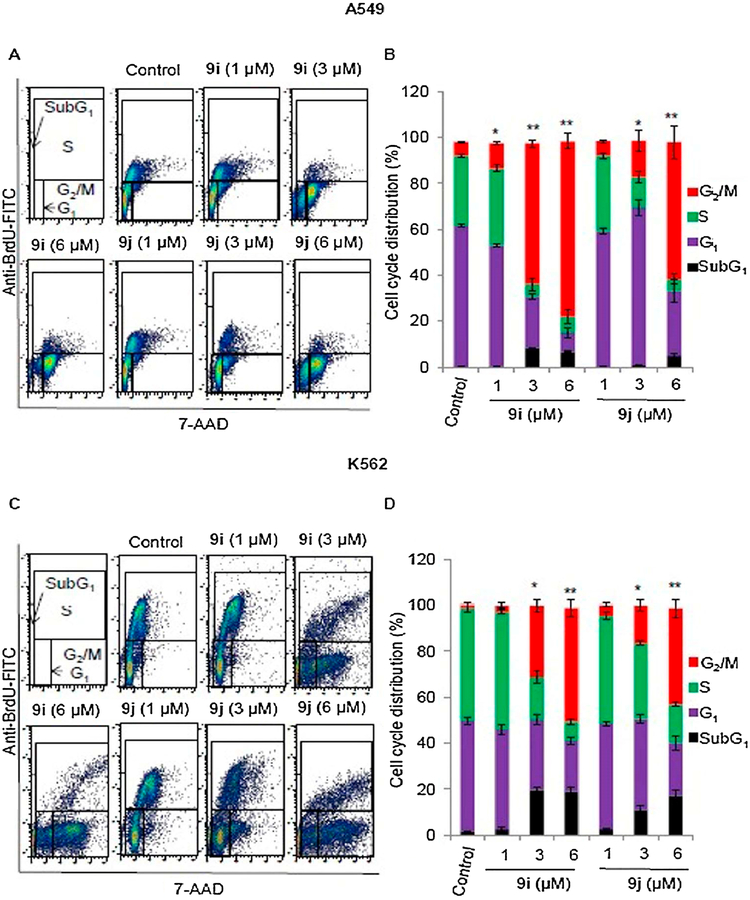

Cell cycle is a series of events that results in cell division, DNA replication, and the generation of two daughter cells. Two classes of genes, oncogenes and tumor suppressor’s genes regulate the cell cycle. Dysregulation of these genes leading to the loss of control over the rate of cell cycle progression, which ultimately results in abnormal cell proliferation [32]. Therefore, the cell cycle plays a key regulatory role in controlling abnormal cell proliferation [33]. Cell cycle progression was analyzed using flow cytometry to determine whether the anti-proliferative effect of compounds 9i and 9j, toward A549 and K-562 cells was associated with the induction of cell cycle arrest.

Flow cytometry results (Fig. 4) indicated that compounds 9i and 9j caused a dose dependent increase in percentage of A549 (Fig. 4A and B) and K-562 (Fig. 4C and D) cells lines in the G2/M phase. Treatment of A549 cells with 1, 3, or 6 μM of 9i or 9j for 24 h, resulted in an increase in the percentages of cells in the G2/M phase – 11, 61.2, and 76.2%, respectively for 9i and 6.22, 15.8, and 59.6%, respectively for 9j – when compared with control cells (5.9%). Similarly, the percentages K-562 cells in the G2/M phase were 2.95, 30.7, and 49.3%, respectively for 9i (1, 3, or 6 μM) and 5.1, 16.6, and 41.7%, respectively for 9j (1, 3, or 6 μM) when compared with control cells (1.79%). Compound 9i was more potent than 9j in both A549 and K-562 cells. Percentages of cells in G1 and S phase were decreased after treatment of either A549 or K-562 cells with 9i or 9j. These results indicated that the inhibition of A549 and K-562 cell proliferation by 9i and 9j can be associated with cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase.

Fig. 4.

Cell cycle analysis of A549 and K-562 cells after treatment with different concentrations (0, 1, 3, 6 μM) of compounds 9i and 9j for 24 h using flow cytometry.(A) Cell cycle distribution in A549 cells. (B) Percentage of of A549 cells (%) in the subG1, G1, S or G2/M phases (C) Cell cycle distribution in K-562 cells. (D) Percentage of of K-562 cells (%) in the subG1, G1, S or G2/M phases. Values are expressed as mean ± SD of three different experiments. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.005 indicate significant differences in percentage of cells in G2/M phase compared with control.

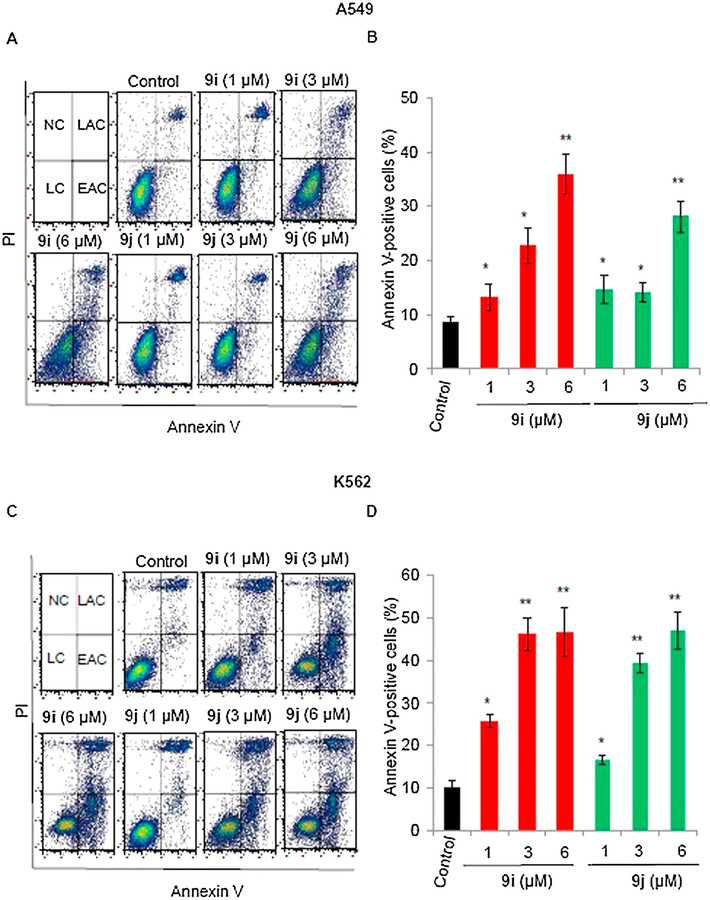

2.2.4. Apoptosis induction in A549 and K-562 cells

To examine whether 9i- and 9j-induced cytotoxicity was associated with apoptosis, we used A549 and K-562 cells and flow cytometry following annexin V-FITC/PI double staining. Treatment of A549 cells with 9i and 9j (1, 3, or 6 μM) for 24 h, did not result in changes in the proportion of apoptotic cells when compared to control cells (data not shown). However, treatment of these cells with the aforementioned compounds for 48 h dramatically increased the proportion of apoptotic cells in a dose-dependent manner; the percentages of apoptotic cells were 13.21, 22.73, and 35.9% for 1, 3, and 6 μM of compound 9i, respectively and 14.68, 14.07, and 28.1% of compound 9j, respectively when compared to control cells (8.59%) (Fig. 5A and B). On the other hand, induction of apoptosis in K-562 cells was observed 24 h after treatment with compounds 9i and 9j. The percentages of apoptotic cells induced by 1, 3 and 6 μM were 25.79, 46.2, and 46.6% for 9i and 16.65, 39.4, and 47.1 for 9j when compared to control cells (9.96%) (Fig. 5C and D). It is clear from these results that 9i and 9j have the ability to induce apoptosis in both A549 and K-562 cells, but K-562 cells were more sensitive to both compounds. Compound 9i appeared to be more potent than 9j against A549 cells, while the compounds exhibited comparable activities against K-562 cells.

Fig. 5.

Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis induced by 9i or 9j (0, 1, 3, or 6 μM) after 24 h in A549 and K-562 cells. Cells that are considered alive are both Annexin V and PI negative, cells that are in early apoptosis are Annexin V positive and PI negative, cells that are in late apoptosis are both Annexin V and PI positive, and dead cells are Annexin V negative and PI positive. The lower-left quadrant represents live cells (LC); the lower-right quadrant, early apoptotic cells (EAC); the upper-right quadrant, late apoptotic cells (LAC); the upper-left quadrant, necrotic cells (NC) (A) Representative cytograms of apoptotic A549 cells. (B) Proportion of annexin V-positive apoptotic A549 cells (C) Representative cytograms of apoptotic K-562 cells. (D) Proportion of annexin V-positive apoptotic K-562 cells. Values are expressed as mean ± SD of three different experiments. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.005 indicate significant differences compared with vehicle.

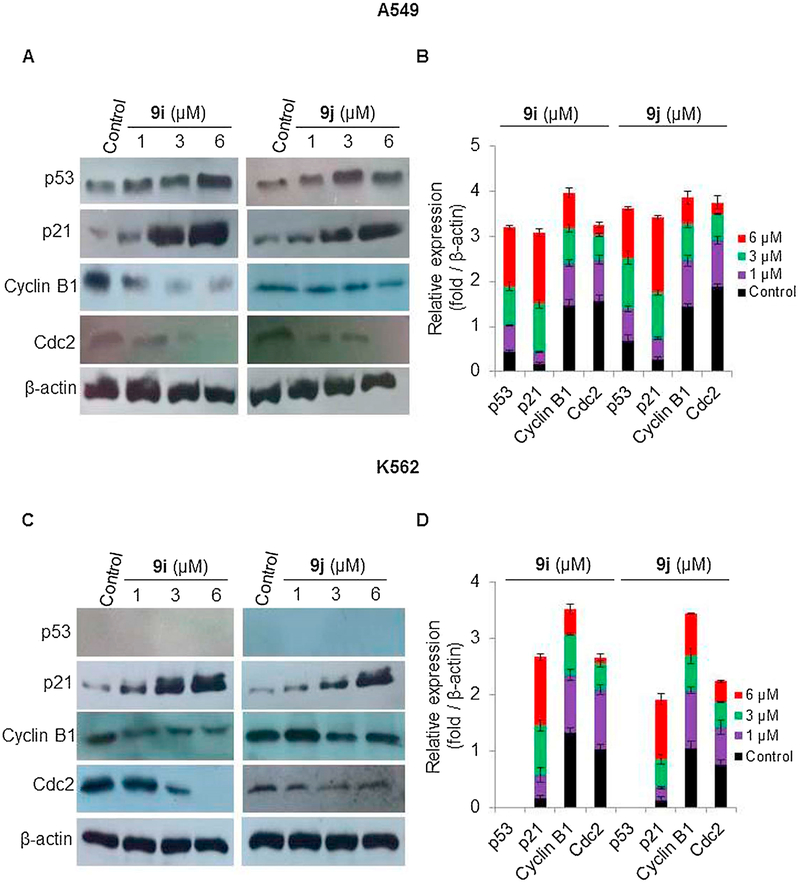

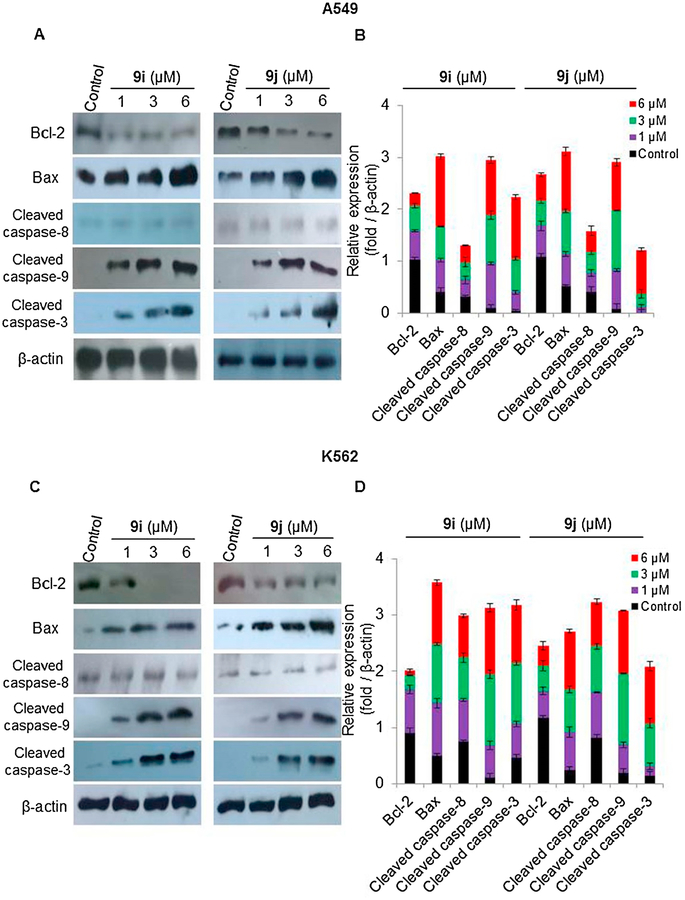

To determine the molecular basis for the induction of G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in A549 and K-562 cells by quinoline-chalcone derivatives, 9i and 9j, the effects of different concentrations (1, 3 and 6 μM) of the aforementioned compounds on the expression of p53, cell cycle regulators (CDK inhibitor (p21), and cyclin B1/Cdc2 complex), anti-apoptotic protein (Bcl-2), as well as pro-apoptotic markers (Bax, and caspases 3, 8 and 9) were tested. Western blot analysis (Fig. 6A–D) showed that 9i and 9j upregulated wild type p53 in A549 cells but have no effect on the non-functional p53 in K-562 cells. 9i and 9j also significantly induced the expression of p21 and attenuated expression of cyclin B1 and Cdc2, in a dose dependent manner, in both A549 (Fig. 6A–B) and K-562 (Fig. 6C–D) cells. These results suggested that the G2/M arrest induced by 9i and 9j might be attributed to p53/p21 pathway in A549 cells and p53-independent p21 induction in K-562 cells. On the other hand, treatment of A549 with 9i or 9j for 48 h resulted in decreased levels of Bcl-2, while the levels of Bax, cleaved caspase 3, and 9 were increased in a dose-dependent manner, and the levels of cleaved caspase 8 were not altered (Fig. 7A and B). Treatment of K-562 cells with the aforementioned compounds for 24 h, resulted in increased levels of Bax, cleaved caspase 3, and 9 in a dose-dependent manner, while the levels of cleaved caspase 8 were not change (Fig. 7C and D). These results indicated that quinoline-chalcone derivatives, 9i or 9j, may induce G2/M arrest and apoptosis via different mechanisms and regardless of the p53 status of the cells.

Fig. 6.

Effect of different concentrations of 9i or 9j (1, 3, or 6 μM) on the expression of p53, p21, cyclin B1 and Cdc2 in A549 and K-562 cells using western blotting analysis. DMSO-treated cells serve as a negative control. β-Actin serves as a loading control (A) Western blotting analysis of A549 cells. (B) Protein expression levels of p53, p21, cyclin B1, and Cdc2 in A549 cells relative to β-Actin were quantified by Image J. (C) Western blotting analysis of K-562 cells. (D) Protein expression levels of p53, p21, cyclin B1 and Cdc2, in K-562 cells relative to β-Actin were quantified by Image J. Values are expressed as means ± SD of three different experiments.

Fig. 7.

Effect of different concentrations of 9i or 9j (1, 3, and 6 μM) on the expression of Bcl-2, Bax, and cleaved caspases (3, 8, and 9) in A549 and K-562 cells using western blotting analysis. DMSO serves as a negative control. β - Actin serves as a loading control (A) Western blotting analysis of A549 cells. (B) Relative protein expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax, and cleaved caspases (3, 8, and 9) in A549 cells compared to β-Actin and quantified by Image J. (C) Western blotting analysis of K-562 cells. (D) Relative protein expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax, and cleaved caspases (3, 8, and 9) in K-562 cells compared to β -Actin and quantified by Image J. Values are expressed as means ± SD of three different experiments.

2.2.5. PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibition

2.2.5.1. In vitro PI3K inhibition assay.

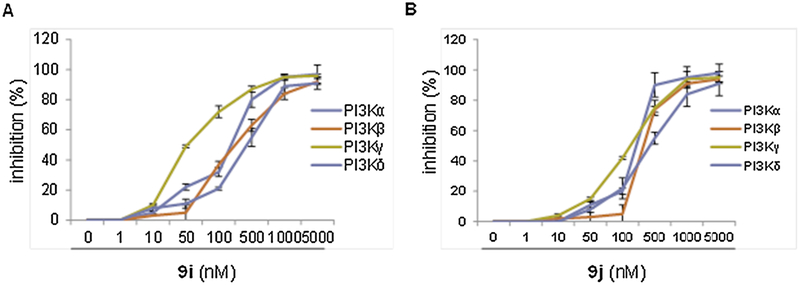

The ability of compounds 9i and 9j to inhibit class I PI3K enzymes was assessed using a commercially available ADP-GloTM kinase detection kit. Results in Fig. 8 and Table 3 showed that the two compounds 9i and 9j have the ability to inhibit the different PI3K isoforms α, β, γ and δ. Compounds 9i and 9j were potent inhibitors of PI3K- γ (with IC50 of 52 and 196.9 nM, respectively), and exhibited moderate potency against PI3K-α (with IC50 of 248.4 and 271.1 nM, respectively) and PI3K- β (with IC50 of 295.8 and 360.2 nM, respectively) and exhibited low potency against PI3K-δ(with IC50 of 438.5 and 473 nM, respectively) (Table 3). In general, compound 9i was more potent than compound 9j against PI3K isoforms.

Fig. 8.

PI3K isomers inhibition (%) induced by different concentrations of 9i and 9j (A) 9i (B) 9j.

Table 3.

IC50s (nM) of compounds 9i and 9j against different PI3K isoforms (PI3K-α, PI3K-β, PI3K-γ and PI3K-δ).

| Compound | IC50 (nM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K-α | PI3K-β | PI3K-γ | PI3K-δ | |

| 9i | 248.4 | 295.8 | 52.03 | 438.5 |

| 9j | 271.1 | 360.2 | 196.9 | 473 |

2.2.5.2. Western blotting analysis.

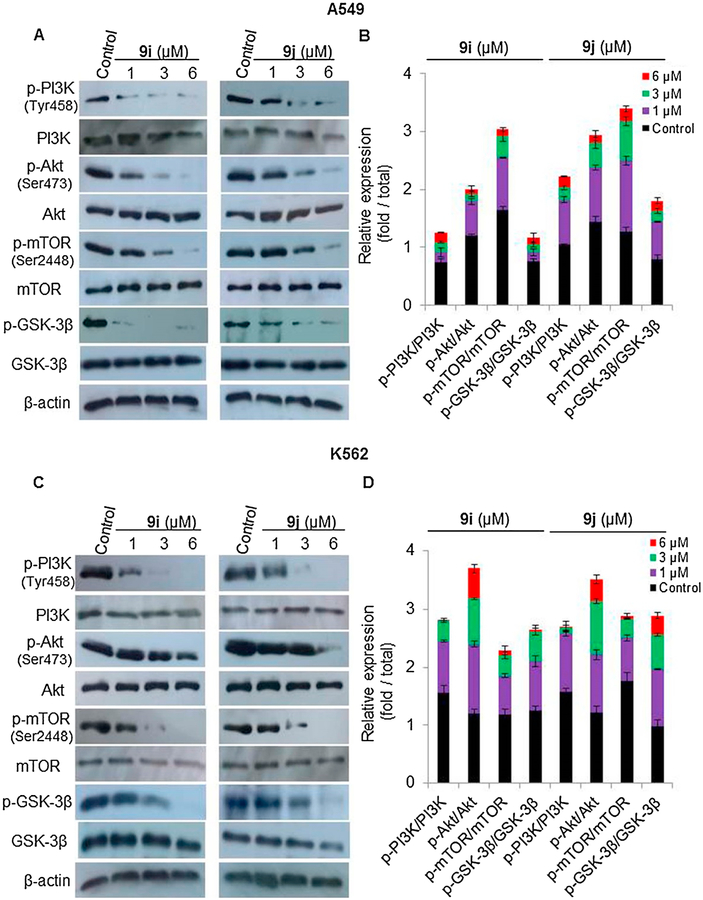

To confirm the inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway by the synthesized hybrids, western blotting analyses were conducted. Both 9i and 9j treatments downregulated the levels of phosphorylated proteins in the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Western blotting analyses revealed that treatment of A549 and K-562 cells with different concentrations of 9i or 9j (1, 3, or 6 μM) resulted in decreases in the levels of phosphorylated PI3K (at Tyr458), Akt (at Ser473), mTOR (at Ser2448), and GSK-3β in a dose-dependent manner in both A549 (Fig. 9A–B) and K-562 (Fig. 9C–D) cells. These results suggested that 9i and 9j attenuated PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in both A549 and K-562 cells. These findings suggest a molecular basis for the induction of G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by 9i and 9j.

Fig. 9.

Effect of compounds 9i and 9j (1, 3, or 6 μM) on the levels of PI3K, p-PI3K, Akt, p-AKT, mTOR, p-mTOR, GSK-3β and p-GSK-3β in A549 and K-562 cells analyzed by western blotting. β-actin serves as a loading control. (A) Levels of p-PI3K, p-Akt, p-mTOR and p-GSK-3β were decreased in A549 cells (B) Protein expression levels (fold/total) of p-PI3K, p-Akt, p-mTOR and p-GSK-3β, in A549 cells relative to their total forms quantified by Image J. (C) Levels of p-PI3K, p-Akt, p-mTOR and p-GSK-3β were decreased in K-562 cells (D) Protein expression levels (fold/total) of p-PI3K, p-Akt, p-mTOR and p-GSK-3β, in K-562 cells relative to their total forms quantified by Image J. The values are the means ± SD of three different experiments.

2.3. Molecular docking study

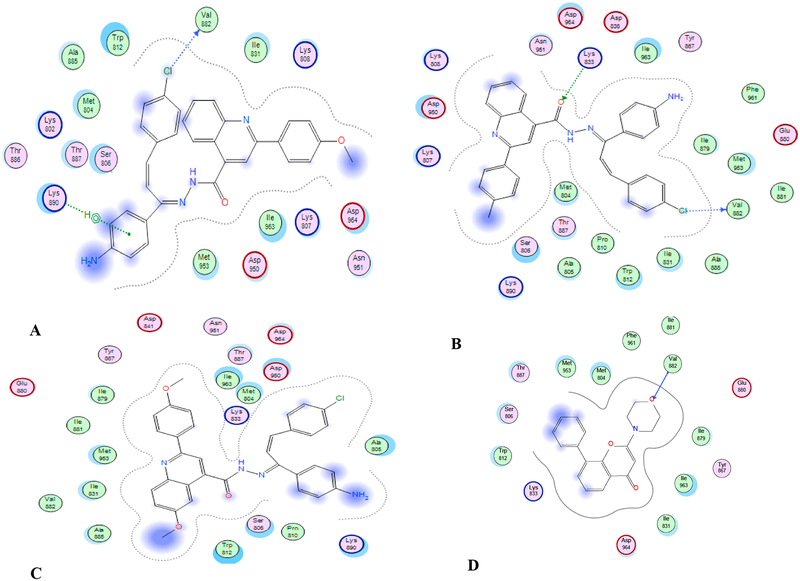

Docking of the compounds 9i, 9j (most active), and 9l (least active), into the active site of different isoforms of PI3K was done in support of the inhibition of PI3K via the interaction of the compounds with amino acid residues within the active site. LY29002 was used as a standard PI3K inhibitor. Docking was done using MOE 2014 software using standard protocols. The study highlighted the formation of stable complex between the 3 compounds and the enzyme active site (energy scores −10 to −13 compared to −10 for LY294002). Docking suggested binding of the active compounds mainly to the hinge region of the enzyme pocket, forming a hydrogen bond with the essential valine (Val 882 for PI3K-γ). Table 4 shows energy scores and possible binding modes of compounds 9i, 9j and 9l with the active site of different isoforms of PI3K (α, δ, γ). While LY294002 forms a single hydrogen bond with Val 882, the chloride atom of compounds 9i and 9j forms a hydrogen bond with Val 882 of PI3K-γ, in addition to extra hydrophobic interaction with Lys 890 for 9i and extra hydrogen bond with Lys 833 for 9j (Table 4, Fig. 10). Hydrogen bond formation and additional 2 or 3 hydrophobic interactions were noticed upon fitting the two compounds with PI3K-α (Table 4, and Supporting information). Compound 9l shows a flipped mode of interaction with the enzyme active site that is different from 9i and 9j. Thus, although 9l fits well into the active site, no significant interactions were observed, Table 4, Fig. 10, Supporting information.

Table 4.

Types of interaction and energy scores for complexes formed from compounds 9i, 9j, 9l and LY294002 with the active site of different PI3K isoforms (γ, α, δ).

| PI3K | 9i | 9j | 9l | LY292004 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | Energy Score interaction |

|

|

|

|

| α | Energy Score interaction |

|

|

|

|

| δ | Energy Score interaction |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 10.

2D drawings of compounds (A) 9i (B) 9j (C) 9l (D) LY294002 interacting with the active site of PI3K-γ. Shown are interactions with different amino acid residues within the active site.

Collectively, the designed compounds offered a new mode of binding that is different from previously studied quinoline or chalcone derivatives. They show no selective binding to any of the PI3K isoforms. Thus, theoretical modelling data went in accordance with the experimental findings obtained.

2.4. Discussion

Lung cancer and leukemia are the most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the world and have limited therapeutic options [1]. Therefore, new therapeutic strategies are urgently needed. Cancer cells exhibit uncontrolled cell proliferation, and anti-cancer drugs inhibit cell proliferation and/or viability, or induce cell death. In the present study, we targeted the prosurvival PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway by the design and synthesis of new quinoline/chalcone hybrids, which were then tested for their ability to inhibit growth of non-small-cell lung cancer and chronic myelogenous leukemia cell lines. The synthesized compounds were screened for their anti-proliferative and cytotoxic effects using three different assays – SRB, BrdU incorporation, and trypan blue exclusion. Our results showed that the synthesized compounds have anti-proliferative and cytotoxic effects on a wide panel of cancer cell lines, in particular chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML; K-562 cells) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; A549 cells). Moreover, compounds were more effective against K-562 than A549 cells. The difference in the response between A549 and K-562 cells may reflect differences in their uptake of the synthesized compounds and/or differences in expression of gene that governs cell cycle and apoptosis [34,35]. Among the compounds tested, 9i and 9j were the most potent and were chosen by the NCI for five-dose assay (Table 1). The presence of electron withdrawing group (chloride) on ring A of the chalcone were predictive of their cytotoxic activity (IC50 of 1.9–18.5 μM for compounds 9g-j against the 2 tested cell lines). Moreover, the activity is optimal with presence of electron donating group (OCH3, CH3) on the 2-phenyl ring on the quinoline moiety, and decreased with an electron withdrawing group or unsubstituted ring.

Compounds 9i and 9j were found to inhibit the different PI3K isoforms in a dose dependent manner, with IC50s of 52–473 nM. These findings were supported by a theoretical docking study that showed the formation of a stable complex between different isoforms of the catalytic p-110 unit and the synthesized compounds. Docking suggested a role for the chloride atom in receptor binding, as well as the stability of the 2 parallel phenyl rings shown in Fig. 2. Presence of the 6-methoxy group at the quinolone ring might hinder binding to enzyme pocket, resulting in lower activity (Fig. 10). Previous literature suggested that the formation of hydrogen bonding with VAL residues present in the hinge region of different PI3K isoforms is critical for PI3K inhibition[21]. The ability of compounds 9i and 9j to form such a hydrogen bonding with only VAL 828 of PI3K-γ (Table 4, Fig. 10) might explain the slight selectivity observed towards this isoform. Western blotting analysis supported the proposed inhibition of PI3K. Compounds 9i and 9j inhibited the phosphorylation of PI3K, AKT, and downstream effectors (including mTOR and GSK-3β) in A549 and K-562 cells.

Like most cytotoxic agents, compounds 9i and 9j inhibited cell cycle and induced apoptosis. Flow cytometry data revealed that the two compounds induced G2/M cell cycle arrest in A549 and K-562 cells (Fig. 5). The observed cell cycle arrest involves upregulation of p21 expression, and downregulation of B1/Cdc2 complex in both A549 and K-562 cells, with p53 activation evident only in A549 cells (Fig. 6). The PI3K/Akt pathway plays an important role in the regulation of G2/M transition [36]. In particular, AKT has been reported to function as a G2/M initiator [37, 38]. In human cancer cells exposed to anticancer agents such as cytotoxic methylating agents, the activation of AKT inhibited G2 checkpoint initiation [38]. Although the mechanistic basis for the release from G2 arrest by AKT is not well defined, this action of AKT appears to involve the accumulation of inactive phospho-Cdc2 and phospho-Cdc25C resulting from an increase in Chk2 activation and resulting in G2/M cell cycle arrest [39]. Therefore, the induction of G2/M cell cycle arrest in the A549 and K-562 cells by 9i or 9j can be attributed to their inhibitory effect on the Akt. The correlation of the inhibition of PI3K\Akt pathway with G2/M cell cycle arrest by other known PI3K inhibitors [40–41] is in line with our data.

Induction of apoptosis significantly affects cell proliferation [42]. Flow cytometry with Annexin V/PI staining suggested that 9i and 9j induced apoptosis in A549 and K-562 cells. The induction of apoptosis can be attributed to caspase-9 activation and Bax and cytochrome c dependent processing resulting from the inhibition of Akt phosphorylation [43,44]. The inhibition of AKT is has also been associated with mitochondrial death signaling induced by various apoptotic stimuli and involving Bcl-2 downregulation, Bax activation, and caspase3/9 activation [45]. Our results are consistent with the reported pro-apoptotic effects of the inhibition of Akt phosphorylation based on the Bcl-2 downregulation, Bax activation, and caspase3/9 activation observed in cells treated with 9i and 9j.

3. Conclusion

A series of novel quinoline chalcone hybrids was prepared and identified with different spectroscopic techniques. The prepared compounds showed remarkable cytotoxic activity against different cancer cell lines. The most active compounds were compound 9i and 9j which induced G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in both A549 and K562 cells. Additionally; the two compounds 9i and 9j had the ability to inhibit the different PI3K isoforms α, β, γ and δ. Both experimental and docking of the compounds 9i and 9j into the active site of different isoforms of PI3K indicated that there is a slight favourable interaction with the γ-isoform with an IC50 = 52 nM. Finally since 9i and 9j showed potent activities on human NSCLC A549 and CML K-562 cells at low μM doses, they are potentially promising drug candidates for NSCLC and CML cancer therapy. However, these compounds should be further assessed in vivo for attenuation of tumor growth. The compounds can also be considered as leads for further development of PI3K inhibitors.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Chemistry section

Chemicals and solvents used were of analytical grade. Progress of the reactions was monitored by thin layer chromatography with methylene chloride as the mobile phase on pre-coated Merck silica gel 60 F254 aluminum sheets. Melting points were determined on Stuart electro-thermal melting point apparatus and were uncorrected. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Advance III 400 MHz (at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Benisweif University, Egypt) and Burker AG, Switzerland, 500 MHz (at the Faculty of pharmaceutical Sciences, Umm Al-Qura University, Mecca, Saudi Arabia) using TMS as reference standard and DMSO-d6 as solvent. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in parts per million (ppm) and coupling constants (J) are expressed in Hertz. The signals are designated as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; m, multiplet. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in parts per million (ppm). LC/MS/MS was carried out using Agilent UPLC/MS/MS 1260 infinity II with 6420 Triple quad LC/MS detector at Faculty of Pharmacy, Minia University, Minia, Egypt

4.1.1. General procedure for synthesis of compounds (3a–d) [46–48]

4-Aminoacetophenon (0.001 mol) and substituted benzaldehydes were mixed and dissolved in minimum amount (3 mL) of ethanol. Sodium hydroxide solution (0.002 mol in water) was added slowly. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h and at room temperature for 24 h. The reaction mixture was then poured into crushed ice. The precipitated solid was filtered, dried and recrystallized from ethanol.

4.1.2. General method for synthesis of compounds (6a–f) [49–51]

Isatin (4a) or 5-methoxyisatin (4b) (10 mmol), 33% potassium hydroxide (10 mL), ethanol (20 mL), and appropriate acetophenone derivative (10 mmol) was mixed and heated under reflux for 18–24 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure; the residue was diluted with water (50 mL) and extracted with diethylether (3 × 50 mL). The aqueous layer was neutralized with 1 M hydrochloric acid. The precipitated solid was filtered, washed with water, dried and crystallized from ethanol.

4.1.3. General method for synthesis of compounds (7a–f) [52–55]

A mixture of the appropriate 4-carboxylic acid 6a–f (10 mmol), absolute ethanol (20 mL) and concentrated sulfuric acid (2 mL) was heated under refluxed for 12–18 h. Excess solvent was removed under reduced pressure; the residue was diluted with water, and then rendered alkaline with concentrated sodium bicarbonate solution. The formed precipitate was filtered off, washed with water and crystallized from ethanol.

4.1.4. General method for synthesis of compounds (8a–f) [51,56–57]

A solution of the isolated esters 7a–f (10 mmol) in ethanol (20 mL), hydrazine hydrate (97%, 3 mL) was added and heated under reflux for 5–8 h. After cooling, the formed precipitate was filtered off, washed with water, dried, and crystallized from ethanol.

4.1.5. General method for synthesis of compounds (9a–t)

To a solution of the prepared chalcones (3a-d) (10 mmol) in aceticacid (20 mL), hydrazides (8a-f, 10 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2–4 h. The solution was poured onto ice water, extracted with dichloromethane (2 × 20 mL) and washed with HCl (10%), water. Organic layer was collected, dried and concentrated under reduced pressure, the precipitate was filtered off, and crystalized from dichloromethane.

4.1.5.1. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-phenylallylidene)-2-phenylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9a).

Yellowish solid (35% yield); mp 289–291 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.41–8.26 (m, 3H),8.24–8.13 (m, 2H), 7.86–7.77 (m, 3H), 7.62–7.56 (m, 4H), 7.49–7.42 (m, 4H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.65–6.53 (m, 1H), 6.43 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.66 (s, 2H, NH2); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 168.53, 163.98, 157.51, 155.98, 151.87, 148.13, 144.23, 142.60, 138.67, 131.66, 130.63, 130.38, 130.06, 129.45, 129.39, 128.75, 128.06, 127.98, 127.74, 127.52, 126.21, 124.39, 123.79, 117.02, 113.68; LC-MS m/z 468.55 (M+H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C31H24N4O: C, 79.46; H, 5.16; N, 11.96; Found: C, 79.86; H, 5.30; N,11.85.

4.1.5.2. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-phenylallylidene)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9b).

Orange solid (38% yield); mp 157–160 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.27 (s, 1H, NH), 8.45–8.40 (m, 3H), 8.39–837 (m, 2H), 8.27–8.21 (m, 1H), 8.18 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.88 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H),7.50 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 3H), 7.28–7.17 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.24, 163.20, 155.00, 149.31, 148.33, 145.35, 144.07, 141.96, 137.31, 135.45, 134.46, 131.03, 130.93, 130.13, 129.57, 129.48, 129.42, 129.20, 128.19, 127.79, 127.02, 125.62, 124.00, 117.59, 116.84; LC-MS m/z 468.55 (M+H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) forC31H23ClN4O: C, 74.02; H, 4.61; N, 11.14; Found: C, 74.34; H, 4.72; N, 11.38.

4.1.5.3. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-phenylallylidene)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9c).

White solid (42% yield); mp 220–223 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.29 (s, 1H, NH), 8.39 (s, 1H), 8.35 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 8.32–8.29 (m, 2H),8.21–8.16 (m, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.86–7.82 (m, 3H), 7.80 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.43 (m, 3H),7.29–7.07 (m, 4H), 3.85 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.09, 164.67, 163.40, 155.92, 149.23, 148.40, 145.35, 141.64, 134.50, 130.97, 130.90, 130.75, 129.91, 129.41, 129.31, 129.19, 129.16, 127.77, 127.46, 127.01, 125.54, 123.57, 117.24, 116.58, 114.80, 55.83; LC-MS m/z 499 (M+H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C32H26N4O2: C, 77.09; H, 5.26; N, 11.24; Found: C, 77.32; H,5.38; N, 11.45.

4.1.5.4. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-phenylallylidene)-2-(4-methylphenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9d).

White solid (44% yield); mp 215–217 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.30 (s, 1H, NH), 8.39 (s, 1H), 8.37–8.32 (m, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 8.26–8.20 (m, 2H), 8.19–8.12 (m, 2H), 7.85 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 3H),7.43–7.35 (m, 3H), 7.28–7.18 (m, 2H), 2.41 (s, 3H, CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.41, 163.40, 156.18, 149.24, 148.40, 145.24, 143.74, 141.76, 140.24, 135.79, 134.53, 130.88, 130.79, 130.52, 130.37, 130.04, 129.41, 129.18, 127.77, 127.71, 127.57, 127.00, 125.60, 123.83, 117.48, 21.41; LC-MS m/z 483 (M+H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C32H26N4O: C, 79.64; H, 5.43; N,11.61; Found: C, 79.90; H, 5.46; N, 11.89.

4.1.5.5. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-phenylallylidene)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-6-methoxyquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9e).

Yellow solid (36% yield); mp 268–270 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.24 (s, 1H, NH), 8.40 (s, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 3H), 8.32 (s, 1H),8.21–8.14 (m, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H),7.67–7.58 (m, 4H), 7.55–7.45 (m, 4H), 7.30–7.10 (m, 2H), 3.91 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.28, 163.39, 158.62, 152.40, 149.23, 145.29, 144.58, 142.29, 140.01, 137.47, 134.93, 134.50, 131.76, 130.91, 130.36, 129.42, 129.40, 129.21, 129.07, 127.77, 127.03, 125.29, 123.43, 118.02, 103.50, 56.05; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C32H25ClN4O2: C, 72.11; H, 4.73; N, 10.51; Found: C, 72.49; H, 4.70; N, 10.36.

4.1.5.6. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-phenylallylidene)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-6-methoxyquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9f).

Orange solid (49% yield); mp 235–237 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm12.24 (s, 1H, NH), 8.41 (s, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.29–8.25 (m, 3H), 8.05 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 7.61–7.59 (m, 1H),7.54–7.45 (m, 5H), 7.14–7.08 (m, 3H), 3.90 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 167.83, 163.59, 161.05, 158.11, 153.47, 149.15, 144.60, 139.81, 134.54, 131.50, 131.17, 131.02, 130.85, 129.40, 129.20, 128.91, 128.73, 127.74, 127.01, 124.73, 123.01, 117.67, 114.72, 112.93, 103.59, 55.97, 55.78; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C33H28N4O3: C, 74.98; H, 5.34; N, 10.60; Found: C, 75.24; H, 5.47; N, 10.89.

4.1.5.7. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)allylidene)-2-phenylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9g).

Yellow solid (44% yield); mp 202–205 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.43–8.29 (m, 5H),8.23–8.05 (m, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H),7.63–7.56 (m, 4H), 7.54–7.47 (m, 4H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.44 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 165.64, 164.00, 157.44, 156.19, 148.51, 147.20, 138.90, 134.38, 132.48, 130.68, 130.38, 130.23, 129.93, 129.43, 129.36, 129.29, 129.07, 128.79, 128.17, 127.75, 127.71, 127.23, 126.46, 117.62, 113.67; LC-MS m/z 483 (M+H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C31H23ClN4O: C, 74.02; H, 4.61; N, 11.14; Found: C, 74.28; H, 4.68; N, 11.40.

4.1.5.8. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9h).

Pale yellow solid (40% yield); mp 272–273 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.28 (s, 1H, NH), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.41–8.39 (m, 3H), 8.38–8.36 (m, 1H),8.26–8.21 (m, 1H), 8.18 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.90–7.86 (m, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H), 7.73–7.69 (m, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.31–7.19 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.29, 163.27, 154.99, 148.32, 147.98, 141.87, 137.30, 135.46, 135.38, 133.43, 133.08, 131.04, 130.78, 130.14, 129.56, 129.53, 129.48, 129.43, 129.33, 128.63, 128.20, 125.59, 123.97, 117.61, 116.86; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C31H22Cl2N4O: C, 69.28; H, 4.13; N, 10.42; Found: C, 69.42; H, 4.05; N, 10.70.

4.1.5.9. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-methoxphenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9i).

Pale yellow solid (50% yield); mp 240–242 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.34 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 8.32–8.28 (m, 2H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H), 7.64 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H),7.21 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 3H), 3.87 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.57, 163.55, 161.42, 161.33, 155.90, 148.40, 147.87, 144.04, 141.64, 135.31, 133.51, 130.97, 130.73, 129.91, 129.85, 129.51, 129.39, 129.30, 129.16, 128.60, 127.45, 125.56, 123.57, 117.26, 114.79, 55.83; LC-MS m/z 533 (M +H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C32H25ClN4O2: C, 72.11; H,4.73; N, 10.51; Found: C, 72.43; H, 4.68; N, 10.69.

4.1.5.10. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-methylphenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9j).

Pale yellow solid (52% yield); mp 239–240 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.37 (s, 1H), 8.32–8.28 (m, 1H), 8.25 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 8.17–8.07 (m, 2H),7.85–7.74 (m, 3H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H), 7.27 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H),7.18–7.12 (m, 1H), 6.44 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 2.40 (s, 3H, CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 164.70, 164.08, 157.46, 156.11, 151.91, 148.45, 147.46, 141.48, 140.03, 135.98, 135.89, 132.47, 130.51, 130.05, 130.00, 129.91, 129.38, 129.20, 128.77, 128.31, 127.64, 127.54, 117.66, 117.48, 113.67, 21.05; LC-MS m/z 514 (M - H)−; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C32H25ClN4O: C, 74.34; H, 4.87; N,10.84; Found: C, 74.51; H, 4.93; N, 11.01.

4.1.5.11. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-6-methoxyquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9k).

Yellow solid (33% yield); mp 279–280 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm12.31 (s, 1H, NH), 8.39 (s, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 3H), 8.32 (s, 1H),8.19–8.15 (m, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H),7.64 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.63–7.60 (m, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H),7.55–7.48 (m, 2H), 7.33–7.24 (m, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 168.76, 163.37, 158.64, 152.32, 151.44, 147.89, 145.06, 144.61, 142.11, 139.82, 137.45, 135.34, 135.26, 134.96, 131.76, 129.53, 129.41, 129.20, 129.08, 128.67, 128.64, 125.13, 123.44, 118.09, 117.41, 56.06; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C32H24Cl2N4O2: C, 67.73; H, 4.26; N, 9.87; Found: C, 67.85; H, 4.32; N, 9.96.

4.1.5.12. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-6-methoxyquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9l).

White solid (34% yield); mp 272–275 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.36 (s, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H), 8.08 (s, 1H), 8.03–7.99 (m, 2H),7.79 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.53–7.49 (m, 3H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 5.66 (s, 2H, NH2), 3.89 (s, 3H, OCH3),3.84 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 171.75, 164.34, 164.26, 160.88, 157.75, 157.63, 151.86, 146.83, 144.70, 132.47, 131.30, 129.30, 129.09, 129.03, 128.78, 128.46, 128.42, 124.43, 122.46, 117.72, 117.65, 116.87, 114.75, 114.69, 113.57,59.36, 55.48; LC-MS m/z 563 (M+H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C33H27ClN4O3: C, 70.39; H, 4.83; N, 9.95; Found: C, 70.79; H, 4.89; N, 10.07.

4.1.5.13. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)allylidene)-2-phenylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9m).

Yellowish white solid (59% yield); mp 233–234 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.15 (s, 1H, NH), 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 8.34–8.32 (m, 2H), 8.24 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.10–8.07 (m, 1H), 7.87 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.71–7.68 (m, 1H), 7.60 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H),6.79 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.07, 163.10, 161.59, 156.26, 155.89, 149.13, 148.41, 145.12, 141.96, 138.51, 130.85, 130.48, 130.36, 130.13, 129.43, 128.60, 127.90, 127.81, 127.68, 127.02, 125.64, 123.98, 117.69, 116.98, 114.92, 55.82; LC-MS m/z 497 (M - H)−; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C32H26N4O2: C, 77.09; H, 5.26; N, 11.24; Found: C, 77.35; H, 5.21; N, 11.47.

4.1.5.14. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9n).

Pale yellow solid (31% yield); mp 260–262 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.14 (s, 1H, NH), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.40–8.34 (m, 3H), 8.33–8.30 (m, 1H),8.23 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 8.20–8.05 (m, 2H), 7.90–7.81 (m, 2H),7.77–7.69 (m, 3H), 7.68–7.59 (m, 3H), 7.14–7.05 (m, 3H), 3.84 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 168.97, 162.98, 161.60, 161.13, 154.99, 149.16, 148.33, 145.17, 142.14, 137.34, 135.43, 130.99, 130.73, 130.11, 129.56, 129.44, 128.61, 128.13, 126.99, 125.65, 124.05, 117.53, 116.80, 114.92, 114.71, 55.83; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C32H25ClN4O2: C, 69.28; H, 4.13; N,10.42; Found: C, 69.42; H, 4.05; N, 10.70.

4.1.5.15. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9o).

Light brown solid (30% yield); mp 200–202 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.36–8.32 (m, 3H), 8.31–8.28 (m, 2H), 8.21 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H),7.64–7.61 (m, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 3H), 7.05 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H),6.79 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.83 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.31, 163.40, 161.51, 161.38, 155.90, 149.05, 148.42, 142.03, 131.11, 131.05, 130.65, 129.87, 129.81, 129.38, 129.29, 129.14, 128.56, 127.32, 127.17, 125.68, 123.71, 117.20, 114.88, 114.77, 114.68, 55.81, 55.38; LC-MS m/z 529 (M+H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C33H28N4O3: C, 74.98; H, 5.34; N, 10.60; Found: C, 75.21; H, 5.42; N, 10.87.

4.1.5.16. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-methylphenyl)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9p).

Yellow solid (35% yield); mp 240–243 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.17 (s, 1H, NH), 8.34–8.31 (m, 2H), 8.28 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.21 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.92–7.79 (m, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 3H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.79 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H),3.84 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.41 (s, 3H, CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.11, 163.13, 161.58, 156.18, 149.10, 148.39, 147.94, 145.09, 141.87, 140.23, 135.80, 130.77, 130.03, 129.42, 128.59, 127.71, 127.57, 127.02, 125.61, 123.87, 117.43, 116.78, 114.91, 114.70, 113.18, 55.82, 21.41; LC-MS m/z 513 (M+H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C33H28N4O2: C, 77.32; H, 5.51; N, 10.93; Found: C, 77.49; H, 5.59; N, 11.20.

4.1.5.17. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-6-methoxyquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9q).

Yellow solid (31% yield); mp 277–279 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.12 (s, 1H), 8.38–8.34 (m, 3H), 8.33–8.30 (m, 2H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.66–7.64 (m, 1H), 7.63–7.60 (m, 3H), 7.53–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 3.90 (s, 1H, OCH3), 3.83 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 163.22, 161.58, 161.33, 158.57, 158.23, 152.41, 149.14, 144.56, 140.13, 137.47, 134.91, 131.73, 129.43, 129.38, 129.19, 129.05, 128.61, 127.00, 125.31, 123.38, 117.93, 117.44, 114.90, 114.72, 103.52, 56.02, 55.81; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C33H27ClN4O3: C, 70.39; H, 4.83; N, 9.95; Found: C,70.56; H, 4.87; N, 10.21.

4.1.5.18. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-6-methoxyquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9r).

Yellow solid (36% yield); mp 237–239 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.09 (s, 1H, NH), 8.33 (s, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H),8.26–8.23 (m, 2H), 8.15–8.00 (m, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H),7.60–7.55 (m, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.19–7.11 (m, 4H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 3.90 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.84 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 169.29, 163.37, 161.55, 161.05, 158.08, 153.47, 148.99, 145.00, 144.59, 139.97, 131.49, 131.18, 129.40, 128.91, 128.74, 128.60, 127.06, 126.84, 124.77, 123.01, 122.63, 117.62, 114.91, 114.73, 103.60, 55.98, 55.82, 55.79; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C34H30N4O4: C, 73.10; H, 5.41; N, 10.03; Found: C, 73.14; H, 5.44; N, 10.21.

4.1.5.19. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-6-methoxyquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9s).

Orange solid (32% yield); mp 225–228 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.15 (s, 1H, NH), 8.38–8.30 (m, 5H), 8.12–8.04 (m, 2H),7.70–7.60 (m, 4H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.45–7.40 (m, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.83 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13 C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 163.23, 158.57, 158.20, 152.40, 151.47, 149.60, 149.35, 149.15, 144.58, 143.85, 140.25, 137.61, 137.50, 134.90, 134.03, 131.73, 129.39, 129.20, 129.05, 127.21, 125.36, 123.41, 122.73, 117.98, 111.98, 108.69, 103.54, 56.08, 56.04, 55.97; LC-MS m/z 593 (M +H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C34H29ClN4O4: C, 68.86; H,4.93; N, 10.79; Found: C, 68.77; H, 4.88; N, 10.64.

4.1.5.20. N’-((Z)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)allylidene)-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-6-methoxyquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (9t).

Orange solid (30% yield); mp 263–265 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.12 (s, 1H, NH), 8.44–8.19 (m, 4H), 8.13–7.97 (m, 3H),7.77–7.36 (m, 3H), 7.33–6.80 (m, 5H), 6.64–6.56 (m, 1H), 6.12–6.03 (m, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.86 (s, 6H, 2OCH3), 3.80 (s, 3H, OCH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 163.36, 161.05, 158.09, 153.47, 151.48, 149.60, 149.29, 144.60, 139.93, 131.50, 131.18, 131.03, 128.92, 127.19, 126.05, 124.77, 123.04, 122.72, 120.45, 117.65, 114.73, 113.16, 112.93, 111.99, 110.93, 108.70, 103.56, 56.09,56.055, 55.99, 55.81; LC-MS m/z 589 (M+H)+; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C35H32N4O5: C, 71.41; H, 5.48; N, 9.52; Found: C, 71.54; H, 5.51; N, 9.40.

4.2. Biology section

4.2.1. Cell culture and reagents

Human lung adenocarcinoma (A549) and chronic myeloid leukemia (K-562) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA) and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich Co., LLC., St. Louis, MO, USA), or Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM, Sigma-Aldrich) respectively, containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich), in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Quinoline-chalcone derivatives were chemically synthesized (9a-t). Cisplatin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All chemicals used in this study were of the analytical or cell culture grade.

4.2.2. NCI screening methodology

The compounds were shipped for anticancer screening to National Cancer Institute, MD, USA. The methodology used for NCI anticancer screening has been described in detail elsewhere [58]. Briefly, the Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay was performed using approximately 60 human tumor cell lines panel derived from nine neoplastic diseases, in accordance with the protocol of the Drug Evaluation Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda. Compounds to be tested were added to the cells at a single concentration (10−5 M) and incubated for 48 h. End point determinations were made with a protein binding dye, SRB. Cell growth was evaluated spectrophotometrically. Results for each compound tested were reported as the percent of growth of the treated cells relative to the untreated control cells.

4.2.3. Proliferation and cytotoxicity assays

Proliferation of for A549 and K-562 cells was quantified as BrdU incorporation using a Cell Proliferation ELISA, BrdU (colorimetric) Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). A549 or K-562 cells were seeded at 5 × 103 cells/well and cultured overnight in a 96-well plate. The cells were treated with 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50 or 100 μM quinoline-chalcone derivatives (9a-t), cisplatin as a positive controls, or DMSO as a negative control for 24 h. BrdU was added at a final concentration of 10 μM and cultured further for 2 h. BrdU incorporation by the cells was quantified according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At least three independent experiments were performed. Percentage of growth inhibition was determined as [1 − (OD of treated cells/OD of control cells)] × 100. To assess the induction cytotoxicity of the synthesized compounds using A549 and K-562 cell lines, cell viabilities were assessed using trypan blue exclusion assay. A549 or K-562 cells were seeded as 5 × 103 cells/well and cultured overnight in a 96-well plate. The cells were treated with 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50 or 100 μM quinoline-chalcone derivatives (9a-t), cisplatin as a positive controls, or DMSO as a negative control for 24 h. The cultured cells were harvested and re-suspended in 100 μL DMEM or IMDM, and the cell suspension was thoroughly mixed with an equal volume of 0.4% trypan blue staining solution (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). Numbers of viable and dead cells were counted using a hemocytometer and the cell viability percentage was determined by dividing the number of viable cells by the number of total cells (viable + dead) and multiplying by 100.

4.2.4. Cell cycle analysis and apoptosis analysis

Cell cycle progression or induction of apoptosis of A549 or K-562 cells was analyzed by a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) using the BD Pharmingen™ FITC-BrdU Flow Kit (BD Biosciences) or the annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining kit (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A549 or K-562 cells were treated with 1, 3 or 6 μM of quinolone/chalcone hybrids; 9i or 9j, or DMSO (vehicle) for 24 h. For each subset, about 10,000 events were analyzed. Quantitative analyses of the FACS data were performed using the FlowJo software (Flowjo, Ashland, OR, USA).

4.2.5. PI3K biochemical assay

The inhibitory effect of compounds 9i and 9j against class I PI3K enzymes were evaluated using ADP-GloTM kinase detection kit (Promega; Madison, WI, USA). PI3K kinase and the substrate PIP2/PS were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). PI3Kα kinase mixture were prepared in kinase buffer at a concentration of 0.375 ng/μL (11 ng/μL, 4.5 ng/μL, 10 ng/μL for PI3Kβ, PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ biochemical assays, respectively). The ATP/substrate mixture contained 5 μM PIP2/PS and 25 μM ATP (25 μM PIP2/PS and 75 μM ATP for PI3Kβ). Different concentrations (0, 1, 10, 50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000 nM) of 9i and 9j were prepared. 2 μL of diluted compound and 4 μL of ATP/substrate mixture were added to individual wells of 384-well assay plates.

The reactions were started by adding 4 μL of each kinase mixture per well. The final volume for the reaction was 10 μL, ATP concentration was 10 μM (30 μM for PI3Kβ), PIP2/PS concentration was 2 μM (10 μM for PI3Kβ), and PI3Kα kinase concentration was 0.15 ng/μL(4.4 ng/μL, 0.15 ng/μL 4 ng/μL for PI3Kβ PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ, respectively). The assay plates were covered and reactions were allowed to proceed for 1 h, after which 10 μL of Kinase GloTM reagent per well was added. The plates were incubated for 40 min, and then 20 μL of kinase detection reagent per well was added. The plates then were equilibrated in the dark for 30 min, after which luminescence was measured and the percentage of inhibition was calculated based on the following equation:

where in RLUcompound is the luminescence reading at a given compound concentration, RLUmin is the luminescence reading at the highest concentration (20 μM, the highest concentration is 2.5 μM for PI3Kα biochemical assay) of positive control to completely inhibit PI3K kinase activity, and RLUmax is luminescence reading in the absence of a compound. IC50 values were determined by Graph Pad Prism 5 (Version5.01, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

4.2.6. Western blotting analysis

After 24 h incubation with 9i, 9j, or DMSO (control), A549 or K-562 cells were harvested, washed twice with chilled PBS, and lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer containing 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml pefabloc SC (4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hidrochloride), a protease inhibitor cocktail, 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4). The cell lysates were kept on ice for 30 min after gently vortex, and then centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel immediately after protein extraction, or otherwise the supernatants were stored at −80 °C until use. The protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad laboratories, CA, USA) according to the instructions of the manufacture. For Western blotting analysis, 30 μg of protein cell lysates were loaded onto a 15% SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins separated on a SDS-PAGE gel were transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The PVDF membrane was incubated in blocking buffer containing 3% non-fat milk powder, 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.5% Tween-20 in PBS for 1 h. Subsequently, the PVDF membrane was incubated with the suitable primary antibody overnight, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technologies) or HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Becton Dickinson Co, Durham, NC, USA) for 1 h with agitation at room temperature. Binding of each primary antibody was detected on an X-ray film (Konica Minolta Medical Imaging, Wayne, NJ, USA) with ECL prime immunodetection reagent (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK).

4.3. Statistical analysis

IC50s were calculated by Graph Pad Prism (Version 5.01, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data shown are represented as means ± SD for three independent experimental results. Student’s t-test was performed to determine the statistical significance between different results and control. Statistical significance was defined as *P < 0.05 or **P < 0.005.

4.4. Molecular docking study

Docking of the synthesized compounds 9i, 9j, 9l, and LY292004 was done on the active sites of different isoforms of PI3K to determine possible binding modes between the compounds and the enzyme catalytic site. Experiments were done on MOE 2014 program. Target compounds were constructed into the builder interface; energy was minimized. X-ray crystallographic structure of the ligand enzyme complex was downloaded from protein data bank (www.rcsb.org). Pdb file codes were 4JPS for PI3K-α, 2WXP for PI3K-δ and 1E7V for PI3K-γ. Enzyme preparations were done next via deleting the legend, adding hydrogen atoms, and the atom connection and type were automatically corrected. Then the potential of these receptors was fixed and docking of the selected structures was done into the 3D structure of the catalytic site of the different isoforms. The poses obtained were studied and the poses showing best ligand enzyme interactions were selected and stored for energy calculations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Authors thank the Development Therapeutics Program of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA, for in vitro evaluation of anticancer activity. The authors would like to thank prof. Akimitsu Konishi, graduate school of medicine, Gunma University, Japan for his comments and suggestions. Thanks offered to Dr. Mohamed Abd El-Wahab, Um Al-Qura University for performing NMR analysis for some of the synthesized compounds.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.10.064.

References

- [1].Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A, Global cancer statistics, 2012, CA Cancer J. Clin 65 (2015) 87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ibrahim AS, Khaled HM, Mikhail NN, Baraka H, Kamel H, Cancer incidence in Egypt: results of the national population-based cancer registry program, J. Cancer Epidemiol 2014 (2014) 437971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jain S, Chandra V, Jain PK, Pathak K, Pathak D, Vaidya A, Comprehensive review on current developments of quinoline-based anticancer agents, Arab. J. Chem (2016), 10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Karthikeyan C, Narayana Moorthy NSH, Ramasamy S, Vanam U,Manivannan E, Karunagaran D, Trivedi P, Advances in chalcones with anticancer activities, Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 10 (2015) 97–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stauffer F, Maira S-M, Furet P, García-Echeverría C, Imidazo [4, 5-c] quinolines as inhibitors of the PI3K/PKB-pathway, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 18 (2008) 1027–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Maira S-M, Stauffer F, Brueggen J, Furet P, Schnell C, Fritsch C, Brachmann S,Chène P, De Pover A, Schoemaker K, Identification and characterization of NVPBEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity, Mol. Cancer Ther 7 (2008) 1851–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lee YH, Jeon S-H, Kim SH, Kim C, Lee S-J, Koh D, Lim Y, Ha K, Shin SY, A new synthetic chalcone derivative, 2-hydroxy-3’, 5, 5’-trimethoxychalcone (DK-139), suppresses the Toll-like receptor 4-mediated inflammatory response through inhibition of the Akt/NF-κB pathway in BV2 microglial cells, Exp. Mol. Med 44 (2012) 369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lin M-L, Chen S-S, Huang R-Y, Lu Y-C, Liao Y-R, Reddy MVB, Lee C-C, Wu TS, Suppression of PI3K/Akt signaling by synthetic bichalcone analog TSWUCD4 induces ER stress-and Bax/Bak-mediated apoptosis of cancer cells, Apoptosis 19 (2014) 1637–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].(a) Grandage VL, Gale RE, Linch DC, Khwaja A, PI3-kinase/Akt is constitutively active in primary acute myeloid leukaemia cells and regulates survival and chemoresistance via NF-kappaB, Mapkinase and p53 pathways, Leukemia 19 (2005) 586–594; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stamatkin C, Ratermann KL, Overley CW, Black EP, Inhibition of class IA PI3K enzymes in non-small cell lung cancer cells uncovers functional compensation among isoforms, Cancer Biol. Ther 16 (2015) 1341–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Courtney KD, Corcoran RB, Engelman JA, The PI3K pathway as drug target in human cancer, J. Clin. Oncol 28 (2010) 1075–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Denley A, Kang S, Karst U, Vogt PK, Oncogenic signaling of class I PI3K isoforms, Oncogene 27 (2008) 2561–2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sui T, Ma L, Bai X, Li Q, Xu X, Resveratrol inhibits the phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway in the human chronic myeloid leukemia K562 cell line, Oncol. Lett 7 (2014) 2093–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].LoPiccolo J, Blumenthal GM, Bernstein WB, Dennis PA, Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: effective combinations and clinical considerations, Drug Resist. Updat 11 (2008) 32–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fillmore GC, Wang Q, Carey MJ, Kim CH, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Lim MS, Expression of Akt (protein kinase B) and its isoforms in malignant lymphomas, Leuk. Lymphoma 46 (2005) 1765–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rudelius M, Pittaluga S, Nishizuka S, Pham TH, Fend F, Jaffe ES,Quintanilla-Martinez L, Raffeld M, Constitutive activation of Akt contributes to the pathogenesis and survival of mantle cell lymphoma, Blood 108 (2006) 1668–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Martelli AM, Nyakern M, Tabellini G, Bortul R, Tazzari PL, Evangelisti C,Cocco L, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway and its therapeutical implications for human acute myeloid leukemia, Leukemia 20 (2006) 911–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Olsen BB, Bjorling-Poulsen M, Guerra B, Emodin negatively affects the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT signalling pathway: a study on its mechanism of action, Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 39 (2007) 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gustafson AM, Soldi R, Anderlind C, Scholand MB, Qian J, Zhang X, Cooper K,Walker D, McWilliams A, Liu G, Szabo E, Brody J, Massion PP, Lenburg ME,Lam S, Bild AH, Spira A, Airway PI3K pathway activation is an early and reversible event in lung cancer development, Sci. Transl. Med 2 (2010) 26ra25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Garber K, Kinase inhibitors overachieve in CLL, Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 13 (2014) 162–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Müller A, Multiple Outcomes for PI3K/Akt/mTOR Targeting in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Lebenswissenschaftliche Fakultät, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wu P, Hu YZ, Small molecules targeting phosphoinositide 3-kinases, Medchemcomm 3 (2012) 1337–1355. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Knight SD, Adams ND, Burgess JL, Chaudhari AM, Darcy MG, Donatelli CA, Luengo JI, Newlander KA, Parrish CA, Ridgers LH, Discovery of GSK2126458, a highly potent inhibitor of PI3K and the mammalian target of rapamycin, ACS Med. Chem. Lett 1 (2010) 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lv X, Ying H, Ma X, Qiu N, Wu P, Yang B, Hu Y, Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel 4-alkynyl-quinoline derivatives as PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitors, Eur. J. Med. Chem 99 (2015) 36–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhang J, Lv X, Ma X, Hu Y, Discovery of a series of N-(5-(quinolin-6-yl) pyridin-3-yl) benzenesulfonamides as PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitors, Eur. J. Med. Chem 127 (2017) 509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang J, Ma X, Lv X, Li M, Zhao Y, Liu G, Zhan S, Identification of 3-amidoquinoline derivatives as PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitors with potential for cancer therapy, RSC Adv 7 (2017) 2342–2350. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Spitzenberg V, König C, Ulm S, Marone R, Röpke L, Müller JP, Grün M,Bauer R, Rubio I, Wymann MP, Targeting PI3K in neuroblastoma, J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 136 (2010) 1881–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mielcke TR, Mascarello A, Filippi-Chiela E, Zanin RF, Lenz G, Leal PC,Chiaradia LD, Yunes RA, Nunes RJ, Battastini AM, Corrigendum to “Activity of novel quinoxaline-derived chalcones on in vitro glioma cell proliferation”[European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 48 (2012) 255–264], Eur. J. Med. Chem 51 (2012) 300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kotra V, Ganapaty S, Adapa SR, Synthesis of a new series of quinolinyl chalcones as anticancer and anti-inflammatory agents, Indian J. Chem. Section B-Org. Chem. Including Med. Chem 49 (2010) 1109–1116. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Abonia R, Insuasty D, Castillo J, Insuasty B, Quiroga J, Nogueras M, Cobo J, Synthesis of novel quinoline-2-one based chalcones of potential anti-tumor activity, Eur. J. Med. Chem 57 (2012) 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tseng CH, Chen YL, Hsu CY, Chen TC, Cheng CM, Tso HC, Lu YJ,Tzeng CC, Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of 3-phenylquinolinylchalcone derivatives against non-small cell lung cancers and breast cancers, Eur. J. Med. Chem 59 (2013) 274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kumar H, Chattopadhyay A, Prasath R, Devaraji V, Joshi R, Bhavana P, Saini P, Ghosh SK, Design, synthesis, physicochemical studies, solvation, and DNA damage of quinoline-appended chalcone derivative: comprehensive spectroscopic approach toward drug discovery, J. Phys. Chem. B 118 (2014) 7257–7266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Van de Ven W, Proto-Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, Introduction Tumor Biol. 6 (1999) 29. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Casimiro MC, Crosariol M, Loro E, Li Z, Pestell RG, Cyclins and cell cycle control in cancer and disease, Genes & Cancer 3 (2012) 649–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Przybylska M, Jozwiak Z, Relevance of drug uptake, cellular distribution and cell membrane fluidity to the enhanced sensitivity of Down’s syndrome fibroblasts to anticancer antibiotic-mitoxantrone, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1611 (2003) 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ertel A, Verghese A, Byers SW, Ochs M, Tozeren A, Pathway-specific differences between tumor cell lines and normal and tumor tissue cells, Mol. Cancer 5 (2006) 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kandel ES, Skeen J, Majewski N, Di Cristofano A, Pandolfi PP, Feliciano CS,Gartel A, Hay N, Activation of Akt/protein kinase B overcomes a G(2)/m cell cycle checkpoint induced by DNA damage, Mol. Cell. Biol 22 (2002) 7831–7841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Liang JY, Slingerland JM, Multiple roles of the PI3K/PKB (Akt) pathway in cell cycle progression, Cell Cycle 2 (2003) 339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hirose Y, Katayama M, Mirzoeva OK, Berger MS, Pieper RO, Akt activation suppresses Chk2-mediated, methylating agent-induced G2 arrest and protects from temozolomide-induced mitotic catastrophe and cellular senescence, Cancer Res. 65 (2005) 4861–4869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kuo PL, Hsu YL, Cho CY, Plumbagin induces G2-M arrest and autophagy by inhibiting the AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in breast cancer cells, Mol. Cancer Ther 5 (2006) 3209–3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lin W, Xie J, Xu N, Huang L, Xu A, Li H, Li C, Gao Y, Watanabe M, Liu C,Huang P, Glaucocalyxin A induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt pathway in human bladder cancer cells, Int. J. Biol. Sci 14 (2018) 418–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lu J, Chen X, Qu S, Yao B, Xu Y, Wu J, Jin Y, Ma C, Oridonin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in hormone-independent prostate cancer cells, Oncol. Lett 13 (2017) 2838–2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Evan GI, Vousden KH, Proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis in cancer, Nature 411 (2001) 342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cardone MH, Roy N, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Franke TF, Stanbridge E,Frisch S, Reed JC, Regulation of cell death protease caspase-9 by phosphorylation, Science 282 (1998) 1318–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fujita E, Jinbo A, Matuzaki H, Konishi H, Kikkawa U, Momoi T, Akt phosphorylation site found in human caspase-9 is absent in mouse caspase-9, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 264 (1999) 550–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jeong SJ, Dasgupta A, Jung KJ, Um JH, Burke A, Park HU, Brady JN, PI3K/AKT inhibition induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in HTLV-1-transformed cells, Virology 370 (2008) 264–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Shoman ME, Abdel-Aziz M, Aly OM, Farag HH, Morsy MA, Synthesis and investigation of anti-inflammatory activity and gastric ulcerogenicity of novel nitric oxide-donating pyrazoline derivatives, Eur. J. Med. Chem 44 (7) (2009) 3068–3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Abdel-Aziz M, Park SE, Abuo-Rahma GA, Sayed MA, Novel Kwon N -4-piper-azinyl-ciprofloxacin-chalcone hybrids: Synthesis, physicochemical properties, anticancer and topoisomerase I and II inhibitory activity, Eur. J. Med. Chem 69 (2013) 427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mourad MA, Abdel-Aziz M, Abuo-Rahma GA, Farag HH, Design, synthesis and anticancer activity of nitric oxide donating/chalcone hybrids, Eur. J. Med. Chem 54 (2012) 907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Muscia GC, Carnevale JP, Bollini M, Asis SE, Microwave-assisted Dobner synthesis of 2-phenylquinoline-4-carboxylic acids and their antiparasitic activities,J. Heterocycl. Chem 45 (2008) 611–614. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Baragaña B, Norcross NR, Wilson C, Porzelle A, Hallyburton I, Grimaldi R,Osuna-Cabello M, Norval S, Riley J, Stojanovski L, Discovery of a quinoline-4-carboxamide derivative with a novel mechanism of action, multistage antimalarial activity, and potent in vivo efficacy, J. Med. Chem 59 (2016) 9672–9685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].El-Feky SA, Abd El-Samii ZK, Osman NA, Lashine J, Kamel MA, Thabet H, Synthesis, molecular docking and anti-inflammatory screening of novel quinoline incorporated pyrazole derivatives using the Pfitzinger reaction II, Bioorg. Chem 58 (2015) 104–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Xi PX, Xu ZH, Liu XH, Cheng FJ, Zeng ZZ, Synthesis, characterization and DNA-binding studies of 1-cyclohexyl-3-tosylurea and its Ni(II), and Cd(II) complexes, Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc 71 (2008) 523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Leardini R, Pedulli GF, Tundo A, Zanardi G, Aromatic annelation by reaction of arylimidoyl radicals with alkynes - a new synthesis of quinolines, J. Chem. Soc.-Chem. Commun (1984) 1320–1321. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zemtsova MN, Zimichev AV, Trakhtenberg PL, Klimochkin YN, Leonova MV, Balakhnin SM, Bormotov NI, Serova OA, Belanov EF, Synthesis and antiviral activity of several quinoline derivatives, Pharm. Chem. J 45 (2011) 267–269. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wang Q, Huang J, Zhou L, Synthesis of quinolines by visible-light induced radical reaction of vinyl azides and α-carbonyl benzyl bromides, Adv. Synth. Catal 357 (2015) 2479–2484. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Xu ZH, Xi PX, Chen FJ, Zeng ZZ, Synthesis, characterization, and DNA-binding of Ln (III) complexes with 2-hydroxybenzylidene-2-phenylquinoline-4-carbonylhydrazone, J. Coord. Chem 62 (2009) 2193–2202. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Metwally KM, Abdel-Aziz LM, Lashine EM, Husseiny MI, Badawy RH, Hydrazones of 2-aryl-quinoline-4-carboxylic acid hydrazides: synthesis and preliminary evaluation as antimicrobial agents, Bioorganic Med. Chem 14 (2006) 8675–8682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Website for National Cancer Institute (dtp.cancer.gov) accessed at March, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.