Abstract

A 15‐year‐old girl suffered recurrent syncopal episodes during 7 years. Events were precipitated by exercise or emotional stress, leading to the diagnosis of reflex syncope. Exercise testing induced recurrent salvos of nonsustained right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia. This arrhythmia is often asymptomatic, reflex syncope is very frequent and both causes are related to the same triggering situations. It was therefore essential to obtain recordings during syncopal events and to observe the clinical evolution under effective treatment in order to make the right diagnosis.

Keywords: child, syncope, ventricular tachycardia

1. INTRODUCTION

Syncope in childhood is common, the vast majority being of reflex origin, with only a minority having a cardiac cause. When a cardiac anomaly is documented in a context of suspected neurally mediated events, a careful workup is mandatory and the potential cardiac cause should not be overestimated nor overlooked.

2. CASE REPORT

A 15‐year‐old girl complained of multiple emotional and postexercise episodes of syncope for 7 years. A few years earlier, those triggering situations led to the diagnosis of reflex syncope and the patient and her family were reassured. Frequent ventricular ectopy was noted on previous electrocardiograms but the patient had no palpitations at the time of syncopal events and the Holter recording showed no malignant arrhythmia. Therefore, ectopy was considered benign and the diagnosis was not further questioned during the multiple visits to the emergency room. When she was finally referred to our cardiology outpatient clinic, the 12‐lead electrocardiogram showed no QT prolongation, no ST segment elevation and premature ventricular contractions with a left bundle branch block and inferior‐axis QRS morphology (Figure 1), consistent with a right ventricular outflow tract origin. A treadmill exercise test was performed. Exercise tolerance was normal and ectopy disappeared with exercise. However, exercise testing reproducibly induced salvos of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia with a maximal heart rate of 143 beats/min during the recovery period. Echocardiogram, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and prolonged head‐up tilt test detected no abnormality. During 24‐hr Holter monitoring ventricular ectopy accounted for 21% of QRS complexes. Interestingly, the monitoring showed some isolated episodes of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia at rest and during moderate physical activities, but also incessant salvos of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia during two syncopal events, the first one a few minutes after a sprint for the line (Figure 2) and another one after she was severely reprimanded by the teacher who believed she was using a phone in the class, confounding the Holter recorder with a mobile (Figure 3). Symptoms and arrhythmia persisted despite administration of atenolol or sotalol but were fully controlled with a calcium channel blocker, Diltiazem (Tildiem Retard 200 mg once daily). Follow‐up Holter recording and repeat exercise tests did not reveal any ectopic beats at all and, most interestingly, no syncopal event was noted since the therapy was introduced almost a year ago, supporting the diagnosis of rhythmic syncope. We offered catheter ablation therapy to the patient, but he so far refused it.

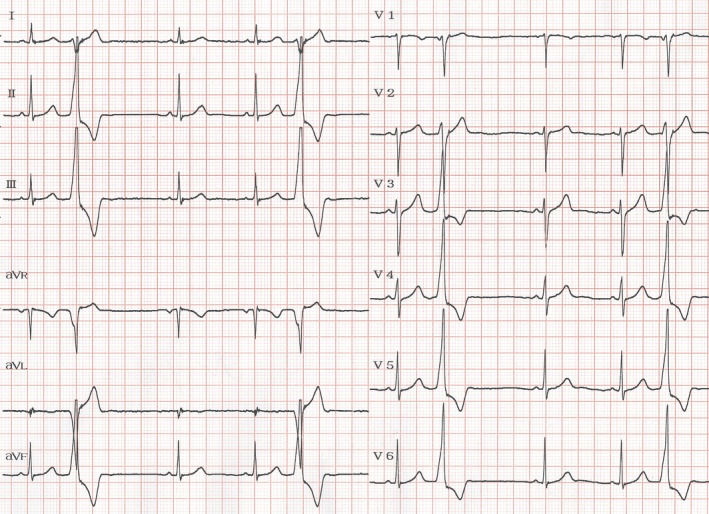

Figure 1.

Resting ECG shows premature ventricular contractions with a left bundle branch block and inferior‐axis QRS morphology

Figure 2.

Holter recording during recovery of vigorous activity shows multiple runs of self‐limiting ventricular tachycardia

Figure 3.

Holter recording during emotional stress shows similar multiple runs of self‐limiting ventricular tachycardia

3. DISCUSSION

Idiopathic ventricular tachycardia most commonly arises from the right ventricular outflow tract. Repetitive monomophic ventricular tachycardia is a subtype of idiopathic tachycardia, that is characterized by frequent short salvos of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (Lemery et al., 1989). It occurs almost exclusively in middle‐aged patients without structural heart disease, but rare pediatric cases were referred for syncope or near‐syncope (Deal et al., 1986; Drago et al., 1999; O'Connor et al., 1996; Pfammater & Paul, 1999; Pfammater, Paul, & Kallfelz, 1995). Its incidence in pediatrics may be estimated around 2,8/1.000.000 childhood years (Roggen, Pavlovic, & Pfammater, 2008) and only 15% of them are symptomatic (Harris et al., 2006). It is generally considered to have an excellent prognosis unless the patient has a history of syncope, very fast tachyarrhythmia or ventricular premature beats with a short coupling interval. Treatment options include antiarrhythmic drugs for patients with mild to moderate symptoms, but catheter ablation is the treatment of choice for drug refractory cases and patients with a potentially malignant form.

Reflex syncope is frequent in teenagers and spells may be triggered by emotional stress or exercise. In some patients, repetitive monomophic ventricular tachycardia is characterized by bursts of nonsustained tachycardia that are typically provoked by emotional stress or exercise, often occurring during the “warm‐down” period after exercise, a time when circulating catecholamines are at peak levels. Being related to the same triggering situations, both causes may coincide. Anyway, the fact that only a minority of patients with repetitive monomorphic ventricular tachycardia are symptomatic highlights the potential role of neurocardiogenic reflex in aggravating hypotension due to the ventricular arrhythmia. Accurate diagnosis is therefore essential to avoid to treat the arrhythmia if it is not responsible for the symptoms. To differentiate both conditions and allow efficient management of the patient, it is important that the result of recordings (provocative testing and long‐term electrocardiographic monitoring while the patient is carrying out daily activities) may be affirmative, which means that they show significant arrhythmia at the time of syncope, and also that both symptoms and arrhythmias are suppressed under antiarrhythmic therapy.

Massin M, Jacquemart C, Khaldi K. Repetitive ventricular tachycardia in a syncopal child: Cause or incidental finding? Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2018;23:e12472 10.1111/anec.12472

REFERENCES

- Deal, B. J. , Miller, S. M. , Scagliotti, D. , Prechel, D. , Gallastegui, J. L. , & Hariman, R. J. (1986). Ventricular tachycardia in a young population without overt heart disease. Circulation, 73, 1111–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drago, F. , Mazza, A. , Gagliardi, M. G. , Bevilacqua, M. , Di Renzi, P. , Calzolari, A. , … & Ragonese, P. (1999). Tachycardias in children originating in the right ventricular outflow tract: Lack of clinical features predicting the presence and severity of the histopathological substrate. Cardiology in the Young, 9, 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K. C. , Potts, J. E. , Fournier, A. , Gross, G. J. , Kantoch, M. J. , Cote, J. M. , & Sanatani, S. (2006). Right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia in children. Journal of Pediatrics, 149, 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemery, R. , Brugada, P. , Bella, P. D , Dugernier, T. , van den Dool, A. , & Wellens, H. J. , (1989). Nonischemic ventricular tachycardia. Clinical course and long‐term follow‐up in patients without clinically overt heart disease. Circulation, 79, 990–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor, B. K. , Case, C. L. , Sokoloski, M. C. , Blair, H. , Cooper, K. , & Gillette, P. C . (1996). Rafdiofrequency catheter ablation of right ventricular outflow tachycardia in children and adolescents. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 27, 869–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfammater, J. P. , & Paul, T. (1999). Idiopathic ventricular tachycardia in infancy and childhood: A multicenter study on clinical profile and outcome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 33, 2067–2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfammater, J. P. , Paul, T. , & Kallfelz, H. C. (1995). Recurrent ventricular tachycardia in asymptomatic young children with an apparently normal heart. European Journal of Pediatrics, 154, 513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roggen, A. , Pavlovic, M. , & Pfammater, J. P. (2008). Frequency of spontaneous ventricular tachycardia in a pediatric population. American Journal of Cardiology, 101, 852–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]