Abstract

Background

To assess the prevalence, the appearance, and the distribution, as well as the fluctuation over time of early repolarization patterns after four years in a female population derived from the French aviation sector.

Methods

This was a retrospective longitudinal study from 1998 to 2010 of a population of female employees who received a full clinical examination and an electrocardiogram (ECG) upon their recruitment and after a period of four years.

Results

A total of 306 women were included (average of 25.87 ± 3.3 years of age). The prevalence of early repolarization was 9.2%. The most common appearance was J‐point slurring for 64.3% (i.e. 20/28 subjects) that occurred in the inferior leads for 28.6% (i.e. 8/28 subjects). After four years, the prevalence was 7.5%, with a regression of this aspect in five of the subjects. There were no changes in the ECG in terms of the distribution and the appearance among the 23 subjects for whom the aspect persisted. Over the course of this four year period all of the subjects remained asymptomatic.

Conclusions

Early repolarization in this largely physically inactive female population was common, and it fluctuated over time. At present, no particular restrictions can be placed on asymptomatic flight crew who exhibit this feature in the absence of a prior medical history for heart disease.

Keywords: aviation medicine, early repolarization, electrocardiogram

1. INTRODUCTION

The French aviation sector is diverse as it is comprised of civilian and military flight crews including aircraft pilots engaged in private or professional settings (airplanes or helicopters), flight attendants, air traffic controllers, flight engineers, and air conveyors (nursing personnel specialized in aerial transport of injured individuals). This population is exposed to significant environmental and professional constraints (isolation in particular), and it undergoes regular medical checkups (associated with very strict performance standards) overseen by doctors specialized in aviation medicine. This medical discipline is subject to international and national legislation and regulations enforced by the Civil Aviation Authority regarding the medical evaluations that apply to flight crews. The proportion of women in specific occupational sectors, such as flight attendants, can be as high as 61% of the total number (Groupement des Industries Françaises Aéronautiques et Spatiales (GIFAS; French Aerospace Industries Association), 2013). One of the roles of doctors specializing in aviation medicine, and for which they may be assisted by a cardiologist (or they may be a cardiologist themselves), is to diagnose heart disease (whether of an acquired or congenital nature) early on. Prior to starting their employment, all flight crew personnel undergo a full clinical examination, as well as an electrocardiogram at each follow‐up consultation. In case of anomalies, members of the military are referred to the cardiology ward of a military hospital to obtain further expert input regarding their condition.

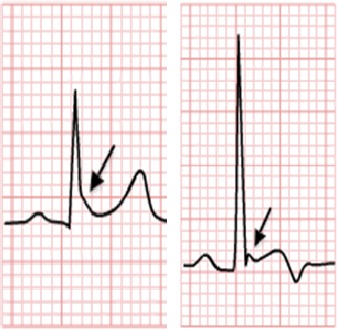

In 2008, Macfarlane et al. redefined early repolarization as elevation of the J‐point (corresponding with the QRS–ST junction) (Macfarlane et al., 2015) that presents as a slurring or a notch equal to or greater than 0.1 mV (Figure 1) on at least two inferior and/or lateral leads (II, III, aVF, I, aVl, V4‐V6, and excluding V1 to V3) with a risk of ventricular fibrillation (Haïssaguerre et al., 2008). Screening for individuals with early repolarization is difficult since, unlike the occurrence of ventricular fibrillation with a healthy heart, it is a common feature (i.e. 3–13%) in the general population (Abe et al., 2007; Noseworthy, Tikkanen, et al., 2011). In light of this, it is difficult to identify the patients in this population who are at risk of sudden death. Identification of this risk is indicated by a family history of sudden death prior to 45 years of age and an unexplained syncope (Abe et al., 2007). The associated ECG features comprise the dynamic nature of the J‐point with an amplitude greater than 0.2 mV, the appearance and the distribution of a J‐point as a notch in the inferior or inferolateral leads, and a horizontal or descending ST segment. This aspect occurs much more frequently in men, and its prevalence can increase as a result of intense physical effort (Noseworthy, Weiner, et al., 2011). It is less common in women, although its incidence varies depending on the study (e.g. 4% in the study by Tikkanen et al. (2009) versus 13% in the study by Uberoi et al. (2011)). In the army, and also in aviation medicine, discovery of early repolarization does not lead to specific cardiological explorations, and it is not a reason to restrict employment either (Vinsonneau et al., 2013). Nonetheless, this approach relies on a stratification of the risk of sudden death, based on ECGs and clinical variables.

Figure 1.

The two ways that early repolarization is typically revealed. Left: appearance of a notch (represented by an arrow, i.e. the presence of a notch or fish hook at the level of the J‐point); right: slurring aspect (represented by an arrow, corresponding with the J‐point becoming diffuse)

2. METHODS

2.1. Aims

The main aim was to assess the prevalence, the appearance, the distribution, as well as the variation over time of early repolarization patterns according to the criteria of Haïssaguerre et al. (2008) after four years in a female population for which we have the responsibility of optimizing the decision in the context of our medical expertise.

2.2. Execution of the study

This retrospective, single center, longitudinal study was carried out over a 12 year period from 1998 to 2010 at the Flight Crew Medical Expertise Headquarters (FCMEH) of the Percy à Clamart Armies Teaching Hospital.

The included population was comprised exclusively of female flight staff employed in the civilian or military sectors. The criteria for inclusion were: subjects over the age of 18 who were asymptomatic in terms of cardiovascular function, with an absence of evidence for familial sudden death prior to the age of 45. The criteria for exclusion comprised all subjects who exhibited an electrical anomaly, such as a complete or partial blockage of the left bundle branch, an auriculo‐ventricular block, a ventricular preexcitation, or a disorder of the supraventricular rhythm.

The study was performed by relying on clinical files and systematic recordings of ECGs in a numerical data base (TRACE MASTER VUE, Philips, Suresnes, France). The ECGs were rendered anonymous by generation of a number‐based identification corresponding with each clinical file.

The subjects underwent a clinical examination and an initial ECG upon their recruitment, followed by a second ECG performed in the setting of a systematic follow‐up after four years. The following cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) were recorded: diabetes (fasting blood glucose level >1.26 g/l), dyslipidemia with hypercholesterolemia (total cholesterol level >2 g/l), current smoker, and a body mass index >30 kg/m². Engagement in physical activities, as defined by a medical‐physiological classification (MPC) based on three categories corresponding to:

MPC1: less than 1 hr of physical activity per week

MPC2: from 1–4 hr of physical activity per week

MPC3: more than 4 hr of physical activity per week.

The first series of ECGs was designated P1 and second (at four years) was designated P2. Each ECG was performed with 12 lead placements, at rest, lying down, and at a speed of 25 mm/s. Each interpretation was performed by two cardiologists. The presence of an early repolarization was denoted as “ER+”, the absence as “ER−”; unclear cases were denoted as “contentious.” With these contentious cases, the ECGs were reinterpreted by a third cardiologist, and in case of a persistent contentious case, or a lack of consensus, the aspect was denoted as being ER−. For each ECG the following information was recorded: the cardiac frequency (as beats per minute), whether there was evidence for left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH): Sokolow–Lyon (S‐wave depth in V1 + R in V5 > 35 mm or S in V2 + RV5 > 35 mm). The corrected T interval (defined by the Bazett formula): . The presence of an early repolarization was defined as an elevation of the J‐point by 1 mm in two concomitant leads (except V1, V2, and V3). The aspect of the ST segment could have an ascending, horizontal, or descending trajectory, as well as the presence of a notch or slurring.

2.3. Statistical analyses

The quantitative variables were expressed as absolute values and percentages. Descriptive statistics were presented following calculation of averages in conjunction with their standard deviations. The Student's t‐test was used to compare the continuous variables. The chi‐square and Fisher's exact tests were used to compare categorical variables following verification of the conditions of execution. The degree of statistical significance was set at 5% (p < .05).

2.4. Ethics considerations

The data collection was performed in an anonymous manner. At no stage were the names of the subjects digitally recorded.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The studied population

Over the course of the inclusion period, 306 women were included. For the most part they were civilian sector employees, and in 95.1% of cases (i.e. 291 of 306 subjects) they were cabin crew. They were 25.87 ± 3.3 year of age, on average. The general characteristics for this population are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The main CVRF was tobacco use, and was found to occur for 123 subjects (i.e. 40.1% of the population). It was a largely physically inactive population, with 170 subjects (i.e. 56% of the population) undertaking less than one hour of physical activity per week. The population as a whole was asymptomatic in regard to cardiovascular function. These results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Professional activity of the population

| Professional activity | Total (n = 306) (%) |

|---|---|

| Military | 15 (4.9) |

| Air traffic controllers | 5 (1.6) |

| Mechanics | 2 (0.7) |

| Fighter pilots | 1 (0.4) |

| Combat helicopter pilots | 7 (2.3) |

| Civilian | 291 (95.1) |

| Cabin crew | 270 (88.2) |

| Airline pilots (class 1) | 16 (5.2) |

| Private pilots (class 2) | 5 (1.6) |

Table 2.

General characteristics of the population

| Total | n = 306 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25.87 ± 3.3 |

| Weight (kg) | 57 ± 6.5 |

| Height (m) | 1.67 ± 0.1 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 20.5 ± 2 |

| Hereditary | 12 (3.9%) |

| Hypertension | 0 |

| Diabetes | 0 |

| Dyslipidemia | 13 (4.2%) |

| Tobacco use | 123 (40.1%) |

| Family history of sudden death/unexplained | 0 |

| Engaged in physical activity < 1 hr per week (MPC3) | 170 (56%) |

| 1 hr/week < Engaged in physical activity < 4 hr/week (MPC2) | 121 (39.5%) |

| Engaged in physical activity > 4 hr/week (MPC1) | 15 (4.9%) |

BMI, body mass index; MPC, medical‐physiological classification.

3.2. First period: analysis of the electrocardiograms

The prevalence of early repolarization pattern (ER+) was 9.2% (i.e. 28 subjects). There were no significant differences (p > .05) in terms of age, in regard to CVRFs, as well as in the extent of engagement in physical activities. The ER+ group had a significantly higher Sokolow–Lyon (SL) index (Table 3). The most common appearance of the J‐point was as a “slurring” pattern for 64.3% (i.e. 20 of 28 subjects) that for 28.6% (i.e. 8 of 28 subjects) was in the inferior leads (D2D3aVf). An association with “notching” was found with 10 subjects (i.e. 35.7%). The ST segment was horizontal or descending in 53.6% of cases. No elevation of the ST segment over 2 mm was seen. These results are summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Clinical and ECG characteristics (period 1)

| Population, n (%) | Total ECG (n = 306) | ER− (n = 278) | ER+ (n = 28) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25.48 ± 3.3 | 25.44 ± 3.2 | 25.8 ± 3.8 | .71 |

| Weight (kg) | 57 ± 6.5 | 57.04 ± 6.6 | 57.6 ± 5.5 | .58 |

| Height (m) | 1.67 ± 0.1 | 1.67 ± 0.1 | 1.66 ± 0.1 | .41 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 20.5 ± 2 | 20.5 ± 2 | 20.8 ± 2 | .22 |

| Hereditary | 12 (3.9%) | 11 (4%) | 1 (3.6%) | 1 |

| Dyslipidemia | 13 (4.2%) | 13 (4.7%) | 0 | .62 |

| Tobacco use | 123 (40.1%) | 108 (38.9%) | 15 (53.6%) | .19 |

| Engaged in physical activity < 1 hr per week (MPC3) | 170 (56%) | 155 (55.8%) | 15 (53.6%) | .98 |

| 1 hr/week < engaged in physical activity < 4 hr/week (MPC2) | 121 (39.5%) | 110 (39.6%) | 11 (39.3%) | .86 |

| Engaged in physical activity > 4 hr/week (MPC1) | 15 (4.9%) | 13 (4.7%) | 2 (7.1%) | .64 |

| ECG Characteristics | ||||

| CF (BPM) | 70.2 ± 11.8 | 70.2 ± 12.1 | 67.5 ± 9 | .13 |

| QTc Bazett (ms) | 393.5 ± 18.1 | 393.4 ± 17.9 | 394.4 ± 20.3 | .61 |

| LVH (Sokolow–Lyon) | 16 ± 5.5 | 15.5 ± 5.1 | 20.8 ± 6.8 | <.001 |

BMI, body mass index; BPM, beats per minute; CF, cardiac frequency; ECG, electrocardiogram; ER−, absence of early repolarization; ER+, presence of an early repolarization; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MPC, medical‐physiological classification; QTc, corrected QT.

Table 4.

Appearance and distribution of the J‐point and aspect of the ST segment

| RP+ P1 (n = 28/9.2%) | RP+ P2 (n = 23/7.5%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CF (BPM) | 67.5 ± 9 | 63.2 ± 9.5 | .11 |

| QTc Bazett (ms) | 394.4 ± 20.3 | 392.2 ± 17 | .67 |

| LVH (Sokolow–Lyon) | 20.8 ± 6.8 | 20.6 ± 7.5 | .93 |

| Appearance and distribution of the J–point | |||

| Slurring | 18 (64.3%) | 15 (65.2%) | .82 |

| Inferolateral slurring (D2D3Vf‐V5V6) | 4 (14.3%) | 4 (17.4%) | 1 |

| Lateral slurring (D1aVl‐V5V6) | 6 (21.4%) | 4 (17.4%) | 1 |

| Inferior slurring (D2D3Vf) | 8 (28.6%) | 7 (30.4%) | .87 |

| Notch | 10 (35.7%) | 8 (35.8%) | .051 |

| Inferolateral notch (D2D3Vf‐V5V6) | 4 (14.3%) | 4 (17.4%) | 1 |

| Lateral notch (D1aVl‐V5V6) | 5 (17.9%) | 4 (17.4%) | 1 |

| Inferior notch (D2D3Vf) | 1 (3.6%) | 0 | |

| Aspect of the ST segment | |||

| Ascending ST segment | 13 (46.4%) | 11 (47.8%) | .86 |

| Horizontal or descending ST segment | 15 (53.6%) | 12 (52.2%) | .85 |

BPM, beats per minute; CF, cardiac frequency; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; QTc, corrected QT.

3.3. Second period (P2): analysis of the electrocardiograms

Four years later, the prevalence of the repolarization aspect pattern was 7.5% (i.e. 23 subjects), and hence five subjects (out of 28) had a regression of this aspect. For the ER+ group, the SL index was significantly higher. The cardiac frequency (CF) was also lower. The predominant aspect of the J‐point was a “slurring” pattern with 15 subjects (i.e. 65.2%), mainly in the inferior leads (D2D3aVf) in 7 subjects of 23 (i.e. 30.4%). The ST segment was horizontal or descending for 52.2% of the cases. No elevation greater than 2 mm of the ST segment was seen. These results are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 5.

Clinical and ECG characteristics (period 2)

| Population, n (%) | Total ECG (n = 306) | ER− (n = 283) | ER+ (n = 23) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.4 ± 3.3 | 29.3 ± 3.2 | 30 ± 3.9 | .40 |

| Weight (kg) | 58.4 ± 6.7 | 58.4 ± 6.8 | 58.4 ± 6.2 | .98 |

| Height (m) | 1.67 ± 0.1 | 1.67 ± 0.1 | 1.66 ± 0.1 | .48 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 20.9 ± 2.1 | 20.9 ± 2.1 | 21.2 ± 2.2 | .61 |

| Hereditary | 12 (3.6%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0 | 1 |

| Dyslipidemia | 11 (3.5%) | 11 (4%) | 0 | – |

| Tobacco use | 110 (35.9%) | 96 (33.9%) | 14 (60.1%) | .02 |

| Engaged in physical activity < 1 hr per week (MPC3) | 186 (60.7%) | 172 (60.8%) | 14 (60.1%) | .83 |

| 1 hr/week < engaged in physical activity < 4 hr/week (MPC2) | 108 (35.3%) | 105 (37.1%) | 8 (34.8%) | |

| Engaged in physical activity > 4 hr/week (MPC1) | 8 (2.6%) | 6 (2.1%) | 2 (8.7%) | .11 |

| ECG characteristics | ||||

| CF (BPM) | 67.6 ± 11.1 | 70 ± 11.1 | 63.2 ± 9.5 | .03 |

| QTc Bazett (ms) | 395.7 ± 16.7 | 396 ± 16.6 | 392.2 ± 17 | .31 |

| LVH (Sokolow–Lyon) | 16.5 ± 5.7 | 16.1 ± 5.4 | 20.6 ± 7.5 | .01 |

BMI, body mass index; BPM, beats per minute; CF, cardiac frequency; ECG, electrocardiogram; ER−, absence of early repolarization; ER+, presence of an early repolarization; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MPC, medical‐physiological classification; QTc, corrected QT.

3.4. Progression of the early repolarization aspect

Four years later, there was a decrease in the prevalence of the ER+ pattern, which was 7.5%, thus amounting to its disappearance in five of the subjects. No clinical events (e.g. sudden death or syncope) were encountered over the course of these four years. There were more smokers among the subjects exhibiting an ER+, relative to the ER− group (p < .05). There were no differences over these two periods regarding the characteristics of the ECGs (e.g. the corrected QT (QTc) and the SL index) as well as for the distribution and the characteristics of the ER+. The subjects for whom the ER+ disappeared also did not exhibit significant differences in terms of their clinical characteristics, as well as in terms of their level of physical activity. In period P2, the SL index was generally higher for the subjects exhibiting a persistent ER+, although the difference was not statistically significant. There were no significant differences regarding the CF and the QTc. There was no change, nor progression, in terms of the distribution and the appearance of the ECGs for subjects for whom the ER+ aspect was persistent. These results are summarized in Tables 4, 6, and 7.

Table 6.

Characteristics of the population with a regression of the early repolarization pattern

| Population, n (%) | Total ECGs (n = 306) | Maintenance of the ER+ (n = 23) | Regression of the ER+ (n = 5) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.4 ± 3.3 | 30 ± 3.9 | 27.8 ± 4.1 | .31 |

| Weight (kg) | 58.4 ± 6.7 | 58.4 ± 6.2 | 62 ± 7.1 | .34 |

| Height (m) | 1.67 ± 0.1 | 1.66 ± 0.1 | 1.65 ± 0.1 | .65 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 20.9 ± 2.1 | 21.2 ± 2.2 | 22.7 ± 2 | .17 |

| Hereditary | 11 (3.5%) | 0 | 2 (40%) | .18 |

| Dyslipidemia | 11 (3.5%) | 0 | 0 | – |

| Tobacco use | 110 (35.9%) | 14 (60.1%) | 2 (40%) | .15 |

| engaged in physical activity < 1 hr per week (MPC3) | 186 (60.7%) | 14 (60.1%) | 3 (60%) | 1 |

| 1 hr/week < Engaged in physical activity <4 hr/week (MPC2) | 108 (35.3%) | 8 (34.8%) | 2 (40%) | |

| Engaged in physical activity > 4 hr/week (MPC1) | 8 (2.6%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0 | 1 |

| ECG characteristics | ||||

| CF (BPM) | 67.6 ± 11.1 | 63.2 ± 9.5 | 65.4 ± 7.6 | .59 |

| QTc Bazett (ms) | 395.7 ± 16.7 | 392.2 ± 17 | 399 ± 33.9 | .70 |

| LVH (Sokolow–Lyon) | 16.5 ± 5.7 | 20.6 ± 7.5 | 16.8 ± 6.7 | .31 |

BMI, body mass index; BPM, beats per minute; CF, cardiac frequency; ECG, electrocardiogram; ER+, presence of an early repolarization; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MPC, medical‐physiological classification; QTc, corrected QT.

Table 7.

Appearance and distribution of the J‐point and aspect of the ST segment (population with a regression of the early repolarization pattern)

| Disappearance ER+P2 (n = 5) (%) | |

|---|---|

| Appearance and distribution of the J‐point | |

| Slurring | 2 (40) |

| Inferolateral slurring (D2D3Vf‐V5V6) | 1 (20) |

| Lateral slurring (D1aVl‐V5V6) | 0 |

| Inferior slurring (D2D3Vf) | 1 (20) |

| Notching | 3 (60) |

| Inferolateral notching (D2D3Vf‐V5V6) | 1 (20) |

| Lateral notching (D1aVl‐V5V6) | 1 (20) |

| Inferior notching (D2D3Vf) | 1 (20) |

| Aspect of the ST segment | |

| Ascending ST segment | 3 (60) |

| Horizontal or descending ST segment | 2 (40) |

ER, early repolarization.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Overview of our results

Our population, comprised specifically of young women who were mainly engaged in the civilian sector and as cabin crew (88%), was asymptomatic in terms of cardiovascular function, and they were largely physical inactive (i.e. 56% of the subjects engaged in less than one hour of physical activity per week). The prevalence of ER+ was 9.2% (i.e. 28 subjects out of 306). The SL index was systematically higher. The most common aspect was a “slurring” (for 64.3% of the subjects), predominantly in the inferior leads (D2D3aVf) in 28.6% of the subjects. A horizontal or descending ST segment was encountered in 53.6% of the cases. At four years, the population as a whole remained asymptomatic at the cardiovascular level (e.g. no syncope and no sudden deaths were noted) and an ER+ pattern was seen for 7.5% of the population (i.e. 23 subjects), thus amounting to a regression in five of the subjects. For the 23 subjects who did not exhibit a regression, there were no changes in regard to the distribution or the aspect of the ER+.

4.2. Prevalence of early repolarization pattern (ER+) in the general population

According to various studies, early repolarization occurs in 1 to 13.1% of the general population (Haïssaguerre et al., 2008; Noseworthy, Weiner, et al., 2011). These studies varied in terms of the age, gender, geographical location, as well as the level of physical activity of the studied populations (Noseworthy, Tikkanen, et al., 2011). The precise redefinition of early repolarization pattern by Haissaguerre et al. has led to a number of epidemiological studies being carried out aimed at accurately determining the prevalence of this aspect. Thus, in 2008, the case–control study by Haïssaguerre et al. encountered a prevalence of 5% in a control group of 412 patients (average of 36.5 ± 12 years of age). In a large study comprising 10,864 patients, Tikkanen et al., (2009) found a prevalence of 5.8% (based on a prevalence of 7.1% in men and 4.6% in women, respectively), in subjects who were 44 ± 8.5 years of age, on average. In the MONICA/KORA study, a prevalence of 13.1% was noted (comprised of 7% men and 6.1% women), in a population of 6 212 patients who were 52 ± 10 years of age, on average (Sinner et al., 2010). Lastly, in 2011, in large American and European cohorts comprising 3,995 and 5,489 patients, respectively, Noseworthy, Weiner, et al. (2011) found a prevalence of 6.1% in the American population and 3.3% in the European population. These studies reveal a different prevalence in men and women, with a higher prevalence in men. In our study, we found a relatively high prevalence of ER+ (i.e. 9.2%). Our study only comprised women who were largely physically inactive and who were relatively young (average of 25.9 ± 3 years of age). Our study also involved a population that was geographically highly variable (coming from all over France), although we did not investigate the subjects’ ethnic backgrounds.

In our study, the predominant aspect was a slurring pattern (64.3%) that occurred mainly in the inferior area (28.6%). The factors associated with an ER+ were a spontaneously lower cardiac frequency and a significantly higher SL index. In 2011, Uberoi et al. studied 29 281 ECGs from a population monitored as outpatients. The subjects exhibiting rhythm disorders and acute cardiac pathologies were excluded from this analysis. In a subgroup of 4041 ECGs, they found 14% early repolarizations. The prevalence of the latter was higher in subjects who had a low cardiac frequency and a short QTc. As in our study, the preferential localization was in the inferior area.

With the exception of the study by Magalski et al. (2008), the prevalence of ER+ is higher in physically active and younger populations. Thus, it is generally higher than what we found for our population of largely physically inactive women. We did not see a significant difference between the moderately (MPC2) and the minimally (MPC3) physically active groups. It is likely that the small number in our series, or the limited level of engagement in physical activity by our subjects, can explain the absence of a difference between these two populations.

4.3. Persistence of the early repolarization pattern

The persistence of the ER pattern on the surface ECG, for a given individual, has not been studied much in the general population. It is nonetheless known that, as for Brugada syndrome, early repolarization is a dynamic phenomenon that evolves over time. Using surface ECGs, in 2011, Noseworthy, Tikkanen, et al. studied the persistence of the ER aspect in 146 male athlete rowers and football players after a period of training lasting 90 days (involving approximately 20 hr of physical activity per week). Prior to the training period the prevalence of ER+ was determined to be 37.2%, and following the training period there was a significant increase, reaching 52.7% (p = .003). This increase in prevalence was also reflected in the inferior localization, as this increased from 4.1% to 8.1% (p = .031). During the post‐training follow‐up (at 21 ± 13 months), there were no cardiovascular events such as unexplained syncope, sudden death, or hospitalization for cardiopathy.

This study highlights the influence of playing sports on the persistence of the ER+ aspect, and the influence of the autonomic nervous system in particular. Our study comprised subjects who had not changed their level of engagement in physical activities and who were also less physically active to begin with. We were hence not able to obtain evidence for this phenomenon. In the general population, the persistence of ER+ is variable, and it can regress with age. Thus, Adhikarla, Boga, Wood, & Froelicher, (2011) have shown a regression of this aspect after 10 years of follow‐up in more than 50% of cases, amounting to 244 subjects who initially exhibited an ER+ (and who were of 42 ± 13 years of age, on average) derived from a cohort of 29,281 subjects. In this study, no cardiovascular events were encountered over the course of the follow‐up. With our population, we saw a regression of ER+ in five subjects (i.e. 17.2%) who were initially ER+, but our study involved far fewer subjects and the follow‐up was shorter (i.e. four as opposed to 10 years).

4.4. Implications for aviation medicine

According to the decree of 04/09/2007 regarding the physical and mental fitness requirements of commercial flight crews, the functioning of the cardiovascular system needs to be ascertained upon each appraisal by a clinical and electrocardiogram examination, and if need be, by appropriate additional examinations. Minor isolated repolarization disorders that disappear with physical exertion can be considered to be incompatible with adequate fitness for duty.

While less frequent among flight crews than in the general population, as the former amounts to a selected population, ischemic heart disease remains a major concern for specialist doctors, and constitutes the number one cause for being deemed to be permanently unfit for flight duties in the course of one's career. A third of ischemic heart disease cases are detected by medical specialists and two thirds are picked‐up due to symptoms, of which 20% occurred in‐flight and that could have potentially result in sudden death. A study carried out with Air France in 1990 showed that out of 85 cases of ischemic heart disease (IHD) declared over 25 years, not a single IHD occurred in‐flight, although 36% started within 24 hr of a flight (Paris, Leduc, & Perrier, 2003). A study carried out in a military setting showed that out of 28 inaugural infarcts identified over 15 years, 20% were detected by a medical specialist. Due to primary prevention and the selection process, not a single one occurred in‐flight.

All of the identified and known causes of sudden death lead to the individual in question being deemed permanently unfit for employment as a member of a flight crew. Several primary rhythm disorders that are now better understood, such as Brugada and long QTc syndromes, are also cause for being deemed to be unfit for duty. New electrocardiograph aspects, such as early repolarization, that have remained little known until now and that have not previously been mentioned in fitness regulatory documents, can pose a problem. Indeed, the recently discovered early repolarization syndrome has changed the perception of this pattern that was initially considered to be benign. This new entity may be responsible for “idiopathic” ventricular fibrillations. The problem for flight crew doctors at air bases, or medical experts in specialist centers is hence to screen for individuals at risk. This process can be aided by stratification of risk. Thus, Tikkanen & Huikuri (2015) have shown that a lateral localization of the ER+, coupled with an ascending ST segment, has a better prognosis than an inferior distribution with a descending or horizontal ST segment. The distribution with the worst prognosis, however, is the presence of an inferolateral localization. The latter was described by Haïssaguerre et al. (2008), and it is deemed to be a poor prognosis, based on the assumption of a channelopathy secondary to a mutation of the KATP channel (which is responsible for an increase in potassium currents). In the same way, an amplitude greater than 0.2 mV and a J‐point with a notching type of transition are also poor prognostic markers. Furthermore, practitioners should consider the observation of rhythmic anomalies (on a surface ECG or by a recording using the method of Holter), with detection of a ventricular hyperexcitability with the presence of short‐coupled ventricular extrasystoles as warning signs. Serious rhythmic events have also been noted following a fluctuation of the J‐point with an increase of its amplitude, which can underlie the start of a ventricular fibrillation. Lastly, a family clinical history (e.g. sudden deaths) and personal history (e.g. recovery from a sudden death episode, documented ventricular fibrillation) are essential features in regard to a suspected malign early repolarization. It should be kept in mind that documented episodes of ventricular fibrillations occur more frequently when at rest (Tikkanen et al., 2011; Uberoi et al., 2011).

With our population, an inferior distribution was found to be predominant with slurring type transitions. An inferolateral localization was found in 8 subjects (i.e. 28.6%) and a “notch” type of transition in half of them (i.e. 14.3%). None of the ECGs that were examined had a J‐point amplitude greater than 0.2 mV. No clinical events were documented, and there were no electrical anomalies or family histories suggestive of channelopathies (e.g. Brugada or long QT syndromes). The ER+ aspect regressed in five subjects, which also suggests fluctuation over time of the latter. No rhythmic event was documented, but the subjects only received a surface ECG, and no other cardiological exploration (e.g. a recording based on the method of Holter or long‐term recordings) was performed, with the population as a whole remaining asymptomatic at the cardiovascular level.

Thus, upon recruitment, or as part of the regular checkups, flight crew doctors can encounter an inferior and/or lateral early repolarization in an asymptomatic patient. The examination should involve probing for palpitations, a history of syncope for the patient, or of sudden death in the family. In the absence of such a record and functional signs, and with a normal cardiovascular examination, it is not necessary for the examination to go beyond an echocardiogram (to rule out a structural cardiopathy) and to specify aptitude constraints. The recommended follow‐ups, with regular checkups at a medical unit and in specialist centers, including performance of an ECG (preferably long‐term, so as to probe for ventricular extrasystoles) remain in force. Probing for events (e.g. sudden death, syncope, malaise) among family members should nonetheless be carefully carried out each year. Currently, there are no specific restrictions for asymptomatic flight crew members without a prior history, and who exhibit early repolarization. There are also no contraindications in terms of medications or being deemed unfit to engage in physical activities. For patients who had an unexplained syncope with an inferior and/or lateral early repolarization, the situation is much more complex. The majority of syncopes with young adults, without cardiopathy or ECG indicative of a channelopathy are vasovagal. While a number of items are often indicative, the diagnosis nonetheless always remains presumptive. Referring the patient to a cardiology unit should be considered, so as to stratify how to proceed in terms of the diagnosis and to justify the fitness assessment. A structural cardiopathy is probed for systematically with flight crew members who have had a syncope, and one should also try to reproduce the phenomenon by recreating the circumstances under which it occurred (e.g. exertion, sudden termination of the exertion, stress, orthostatism (tilt‐test)). In case of symptomatic early repolarization, these arrhythmias nonetheless most often occur irrespective of the situation (41%), or at rest (36%), and sometimes even while asleep (20%) (Tikkanen et al., 2011). In case of unexplained syncope, use of an implantable Holter recorder is a useful diagnostic tool that needs to be considered on a case by case basis. In the first instance, as it is nonspecific, an electrophysiological examination is not indicated. Implantation of an automatic defibrillator is a consideration for primary prevention with asymptomatic subjects (Priori et al., 2013, Priori & Blomstrom‐Lundqvist, 2015) who have a family history of sudden death (particularly if the latter occurred without explanation and at a young age). It is also a consideration when the patient's electrocardiogram exhibits ECG features indicative of a poor prognosis, such as a J‐point amplitude greater than 0.2 mV or fluctuation of the J‐point. New diagnostic, genetic, and therapeutic studies will be required before a definitive approach can be provided in case of unexplained syncope associated with early repolarization.

4.5. Study limitations

This was a retrospective monocentric study performed over a relative short period of time (i.e. follow‐up at four years) with a specifically female population. This population was, however, heterogeneous and representative of the female population in general.

5. CONCLUSION

In our population of young, active, and asymptomatic women, the prevalence of the ER pattern was mainly a slurring type. This aspect fluctuated over time, and it was difficult to differentiate the extrinsic and intrinsic factors that influence the presence of this pattern.

Aviation medicine does not currently specify employment restrictions for commercial flight crews when an asymptomatic early repolarization pattern is found. The diagnostic strategy and the therapeutic approach are based on the dichotomy of the risk as a function of the symptomatology and prior personal and family histories. Reliance of the medical expert on a cardiologist can help with deciding in regard to fitness for in‐flight duties and to hierarchize this diagnostic approach. Indeed, in 2015, the challenge for doctors is to screen for malignant forms of early repolarization.

Rohel G, Perrier E, Delluc A, et al. Progression of early repolarization patterns at a four year follow‐up in a female flight crew population: Implications for aviation medicine. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2017;22:e12451 10.1111/anec.12451

REFERENCES

- Abe, A. , Yoshino, H. , Ishiguro, H. , Tsukada, T. , Miwa, Y. , Sakaki, K. , … Ikeda, T. (2007). Prevalence of J waves in 12‐lead electrocardiogram in patients with syncope and no organic disorder. Journal of Cardiovascacular Electrophysiology, 18, S88. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikarla, C. , Boga, M. , Wood, A. D. , & Froelicher, V. F. (2011). Natural history of the electrocardiographic pattern of early repolarization in ambulatory patients. American Journal of Cardiology, 108, 1831–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groupement des Industries Françaises Aéronautiques et Spatiales (GIFAS; French Aerospace Industries Association) (2013). Situation de l'emploi 2012–2013. Retrieved from: http://www.gifas.asso.fr.

- Haïssaguerre, M. , Derval, N. , Sacher, F. , Jesel, L. , Deisenhofer, I. , de Roy, L. , … Clémenty, J. (2008). Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. New England Journal of Medicine, 358, 2016–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, P. W. , Antzelevitch, C. , Haissaguerre, M. , Huikuri, H. V. , Potse, M. , Rosso, R. , … Yan, G. X. (2015). The early repolarization pattern: A consensus paper. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 66, 470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalski, A. , Maron, B. , Main, M. , McCoy, M. , Florez, A. , Reid, K. J. , … Browne, J. E. (2008). Relation of race to electrocardiographic patterns in elite American football players. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 51, 2250–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy, P. A. , Tikkanen, J. T. , Porthan, K. , Oikarinen, L. , Pietilä, A. , Harald, K. , … Huikuri, H. V. (2011). The early repolarization pattern in the general population. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 57, 2284–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy, P. A. , Weiner, R. , Kim, J. , Keelara, V. , Wang, F. , Berkstresser, B. , … Baggish, A. L. (2011). Early repolarization pattern in competitive athletes: Clinical correlates and the effects of exercise training. Circulation, Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 4, 432–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris, J. F. , Leduc, P. , & Perrier, E. (2003). Mort subite d'origine ischémique en aéronautique. Médecine Aéronautique et Spatiale, 43, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Priori, S. G. , & Blomstrom‐Lundqvist, C. (2015). 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death summarized by co‐chairs. European Heart Journal, 36, 2757–2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priori, S. G. , Wilde, A. A. , Horie, M. , Cho, Y. , Behr, E. R. , Berul, C. , … Tracy, C. (2013). HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: Document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm: the Official Journal of the Heart Rhythm Society, 10, 1932–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinner, M. F. , Reinhard, W. , Müller, M. , Beckmann, B. M. , Martens, E. , Perz, S. , … Kääb, S. (2010). Association of early repolarization pattern on ECG with risk of cardiac and all‐cause mortality: A population‐based prospective cohort study (MONICA/KORA). PLoS Medicine, 7, e1000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen, J. T. , Anttonen, O. , Junttila, M. J. , Aro, A. L. , Kerola, T. , Rissanen, H. A. , … Huikuri, H. V. (2009). Long‐term outcome associated with early repolarization on electrocardiography. New England Journal of Medicine, 361, 2529–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen, J. T. , & Huikuri, H. V. (2015). Characteristics of “malignant” vs. “benign” electrocardiographic patterns of early repolarization. Journal of Electrocardiology, 48, 390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen, J. T. , Junttila, M. J. , Anttonen, O. , Aro, A. L. , Luttinen, S. , Kerola, R. , … Huikuri, H. V. (2011). Early repolarization: Electrocardiographic phenotypes associated with favorable long‐term outcome. Circulation, 123, 2666–2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uberoi, E. , Jain, N. A. , Perez, M. , Weinkopff, A. , Ashley, E. , Hadley, D. , … Froelicher, V. (2011). Early repolarization in an ambulatory clinical population. Circulation, 124, 2208–2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinsonneau, U. , Pinon, B. , Paleiron, N. , Rohel, G. , Piquemal, M. , Desideri‐Vaillant, C. , … Paule, P. (2013). Prevalence of early repolarization patterns in a French military population at low cardiovascular risk: Implications for preventive medicine. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, 18, 436–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]