Abstract

Brugada and long QT‐3 syndromes are two allelic diseases caused by different mutations in SCN5A gene inherited by an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance. Both of these syndromes are ion channel diseases of the heart manifest on surface electrocardiogram by ST‐segment elevation in the right precordial leads and prolonged QTc interval, respectively, with predilection for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and sudden death, which may be the first manifestation of the disease. Brugada syndrome usually manifests during adulthood with male preponderance, whereas long QT3 syndrome usually manifests in teenage years, although it can also manifest in adulthood. Class IA and IC antiarrhythmic drugs increase ST‐segment elevation and predilection for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation in Brugada syndrome, whereas these agents shorten the repolarization and QTc interval, and thus may be beneficial in long QT‐3 syndrome. Beta‐blockade also increases the ST‐segment elevation in Brugada syndrome but decreases the dispersion of repolarization in long QT‐3 syndrome. Mexiletine, a class IB sodium channel blocker decreases QTc interval as well as dispersion of repolarization in long QT‐3 syndrome but has no effect on Brugada syndrome. The only effective treatment available at this time for Brugada syndrome is implantable cardioverter defibrillator, although repeated episodes of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia can be treated with isoproterenol. In symptomatic patients of long QT‐3 syndrome in whom the torsade de pointes is bradycardia‐dependent or pause‐dependent, a pacemaker could be used to avoid bradycardia and pauses and an implantable cardioverter defibrillator is indicated where arrhythmia is not controlled with pacemaker and beta‐blockade. However, the combination of new devices with pacemaker and cardioverter‐defibrillator capabilities appear promising in these patients warranting further study.

Keywords: Brugada syndrome, long QT syndrome, ion channel diseases, ion channelopathies, primary electrical diseases of the heart, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, torsade de pointes, sudden cardiac death, sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (SADS), sudden unexplained death syndrome (SUDS)

Brugada syndrome is characterized by a pattern of right bundle branch block with ST segment elevation in right precordial leads on surface electrocardiogram with predilection for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death, and long‐QT syndrome is characterized by prolongation of QT interval with predilection for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. 1 , 2 Both of these syndromes characterize in a group of diseases described as ion channel diseases or ion channelopathies of the heart (Table 1). Other diseases in this group include Lenegre‐Lev disease, familial (catecholaminergic) polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and possibly short QT syndrome and idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. 3 Ion channel diseases of the heart are caused by genetic defects in the ion channel proteins located on the cell membrane (Brugada syndrome, long QT syndrome, Lenegre‐Lev disease) or on the membrane of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (familial polymorphic ventricular tachycardia). These abnormal ion channels result in altered conduction of the ions across membranes, thus causing disturbance in the electrical current flow in the heart, leading to the term primary electrical diseases of the heart. The ion channelopathies of the heart are inherited by an autosomal dominant pattern but with a variable penetrance. Patients with these diseases have otherwise structurally and functionally normal hearts, and sudden cardiac death might be the first manifestation of the disease.

Table 1.

Ion Channel Diseases of the Heart (Primary Electrical Diseases of the Heart)

| I. Cell membrane ion channelopathies |

| A. Sodium channel diseases |

| Brugada syndrome (I Na) |

| Long QT‐3 syndrome (I Na) |

| Lenegre‐Lev disease (I Na) |

| B. Potassium channel diseases |

| Long QT‐1 syndrome (I Ks) |

| Long QT‐2 syndrome (I Kr) |

| Long QT‐5 syndrome (I Ks) |

| Long QT‐6 syndrome (I Kr) |

| II. Sarcoplasmic reticulum ion channelopathies |

| Calcium‐release channel disease |

| Familial polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (RyR2) |

| III. Possible ion channelopathies of unknown ion channels* |

| Long QT‐4 syndrome |

| Short QT syndrome |

| Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation |

I Kr= Rapidly activating delayed rectifier potassium channel; I Ks= Slowly activating delayed rectifier potassium channel; I Na= Voltage‐dependent sodium channel; RyR2 = Ryanodine Receptor type 2.

*Ion channels not known at present time.

Death in patients with the primary electrical diseases of the heart usually occurs in adolescence or young adulthood except in those with Lenegre‐Lev disease, which primarily affects the cardiac conduction system and manifests with various degrees of atrioventricular block and intraventricular conduction delays usually at middle or old age, and may cause sudden death because of asystole or torsade de pointes (bradycardia or pause dependence) in spite of an otherwise normal QTc interval. Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation is a group of diseases that have not been well characterized. Brugada syndrome has been branched off from the idiopathic ventricular fibrillation after Brugada and Brugada reported the first eight cases of this characteristic syndrome in 1992, and at the present time it is believed to be responsible for about 20% of deaths in patients with structurally normal hearts. 4

ETIOLOGY AND GENETICS

Both Brugada syndrome and long QT‐3 syndrome share the same position on chromosome 3P21–24, and are inherited by an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance. 5 , 6 Brugada syndrome is usually caused by mutations in a sodium channel gene, SCN5A, which encodes for a cardiac sodium channel located in the cell membrane. However, there are reports of Brugada syndrome with normal SCN5A gene where loci distinct from SCN5A have been reported, but the candidate genes have not been identified. 7 On the other hand, of six forms of long QT syndrome (long QT‐1 to long QT‐6) caused by multiple genetic defects, five of those genes have been identified, and four (KCNQ1, HERG, KCNE1, KCNE2) of these are related to potassium ion channels and one (SCN5A) to the sodium ion channel. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 As mutations in SCN5A gene cause long QT‐3 syndrome, both Brugada syndrome and the long QT‐3 syndrome are two allelic diseases caused by different mutations in the SCN5A gene.

The sodium channels are voltage‐gated membrane proteins responsible for the initial phase (phase 0) of the action potential in most excitable cells. 14 They open briefly upon depolarization and then rapidly inactivate (by a mechanism conferring fast inactivation) contributing to the initiation and conduction of action potential. On repetitive and prolonged depolarization, sodium channels enter most stable nonconducting states by a distinct mechanism called slow inactivation. 15 Although it is the alpha subunit of the sodium channel that is involved in both Brugada and long QT‐3 syndromes, the functional consequences of mutations in Brugada syndrome are different from those in long QT‐3 syndrome. Mutations in Brugada syndrome are those of the loss in function of the sodium channel during the early part of phase I of the action potential, whereas the mutations in the long QT‐3 syndrome are those of the gain in the function of sodium channel by their failure to close at the right time. The gain in function mutation in the long QT‐3 syndrome results in a slow and constant entry of sodium during phase II of the action potential.

In patients with Brugada syndrome, splice‐donor, frame‐shift, and missense types of mutations have been identified in SCN5A gene. 16 The SCN5A mutations in LQT‐3 syndrome are missense and deletion. In addition, an overlap syndrome has been reported. 17 , 18 , 19 Priori et al. 17 reported that, upon flecainide challenge, certain long QT‐3 patients demonstrate not only the prolonged QT interval but also the ST‐segment elevation in the right precordial leads. During flecainide administration to 13 patients from 7 long QT‐3 families, QT, QTc, JT, and JTc interval shortening were observed in 12 of 13 patients, and surprisingly, concomitant ST‐segment elevation of more than 2 mm in leads V1–V3 was observed in 6 of these 13 patients. This study demonstrated the existence of an association between long QT‐3 and Brugada syndrome and implied that both syndromes may share a common genotype. In another study, Bezzina et al. 18 described a family of a large 8‐generation kindred characterized by a high incidence of nocturnal sudden death, with QTc prolongation and Brugada‐type ECG pattern occurring in the same subjects. In affected individuals, the QRS complex and QTc intervals were prolonged and there was an ST‐segment elevation in the right precordial leads. Twenty‐five family members had died suddenly, 16 of them during the night. An insertion mutation was linked to the phenotype and was identified in all the electrocardiographically affected family members.

Regarding the background of the genetic overlap between Brugada and long QT‐3 syndromes, Veldkamp et al. 19 reported a single SCN5A insertion mutation that may present with features of both Brugada syndrome and long QT‐3 syndrome by influencing diverse components of sodium channel gating function. This mutation produces an early sodium channel closure, but augments the late sodium channel current due to a slower recovery of the sodium channels from inactivation, as well as due to a defect in the inactivation of the channel, which is common for both Brugada syndrome and long QT‐3 syndrome phenotypes.

DEMOGRAPHICS

The exact prevalence of Brugada syndrome and long QT‐3 syndrome is not clearly known because Brugada syndrome was identified in the last decade, and, although the long QT syndrome was known before, various genetic and ion channel forms of the syndrome were characterized only in the last decade. The incidence of Brugada syndrome has been reported ranging from as low as one in 1 million to as high as one in 1000, depending upon the geographical region and the population studied. 20 , 21 Both these syndromes have been reported worldwide. Probably the highest incidence of Brugada syndrome is present in the South Eastern regions of Asia. 20 , 21 , 22 Brugada syndrome usually manifests during adulthood with male prevalence eight times more than females, and the mean age of sudden death in victims of Brugada syndrome is about 35 to 40 years. On the other hand, long QT‐3 syndrome usually manifests in preteenage or in teenage years, although it can also manifest in adulthood. 23 About 10% of patients with long QT syndromes are of the long QT‐3 subtype.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Although Brugada syndrome and long QT‐3 syndrome are similar genotypically, both syndromes encompass different phenotypic characteristics because of the difference in the functional consequences of the mutations causing these syndromes. In the long QT‐3 syndrome, the gain in function in the sodium channel causes continued entry of sodium ions into the cell during phase II of repolarization, thereby lengthening the repolarization, which is manifested on the surface electrocardiogram as a prolonged QT interval, whereas in Brugada syndrome the sodium channel loses the function and is closed before time; therefore there is no prolongation in the repolarization and the QT interval remains essentially unchanged. 16

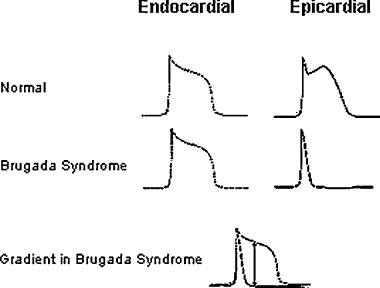

The ST segment elevation in right precordial leads in Brugada syndrome represents the early repolarization of the right ventricular subepicardial myocardium. 24 , 25 In humans, the transient outward current Ito is most prominent at the subepicardial layer compared to the other layers of myocardium. The Ito is an initial repolarization current underlying inscription of the phase 1 of the action potential. In Brugada syndrome where the depolarizing inward‐directed rapid sodium current is terminated earlier, the Ito is left relatively unopposed, and can easily overwhelm the inward calcium current ICa resulting in an earlier repolarization, which is more pronounced in subepicardial myocardium of the right ventricle because this area is rich in Ito current. With an earlier repolarization in the subepicardial regions of right ventricle, an early loss of action‐potential dome occurs while the other layers of myocardium maintain the normal duration of action potential resulting in a wider transmural dispersion of the repolarization and an electrical gradient between epicardial and endocardial regions of the myocardium (Fig. 1). As a result, the subepicardial myocardium with a shorter duration of action potential and a shorter refractory period could be excited by the adjacent cells with the normal duration action‐potential and refractory period resulting in a phase II reentry‐based polymorphic ventricular tachycardia characteristic of Brugada syndrome. In long QT‐3 syndrome, prolonged repolarization results in the formation of early afterdepolarizations in phase III of the action potential. These early afterdepolarizations trigger ventricular ectopics, which initiate a short‐long‐short cycle, starting torsade de pointes in an underlying myocardial substrate of increased dispersion of repolarization with partial recovery of action potential, especially in the middle layers (M cell) of myocardium. 26 , 27 , 28 There is also a marked trans‐myocardial dispersion due to a slower repolarization in M cells because M cells possess the lowest concentration of slow activating, delayed rectifying IKs current. 26 , 27 , 28

Figure 1.

Shortening of the duration of action potential in the epicardial region in Brugada syndrome causes an electric gradient and potential for reentry.

ELECTROCARDIOGRAM

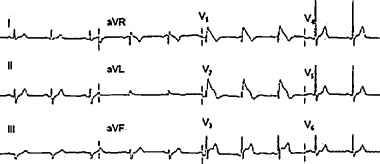

Both Brugada syndrome and long QT‐3 syndrome have electrocardiographic patterns that can facilitate the diagnosis. The electrocardiogram in Brugada syndrome is characterized by a right bundle branch block pattern with ST‐segment elevation in precordial leads V1, V2, and V3 (Fig. 2). ST‐segment elevation could be of the coving type or the saddle type. A coving‐type ST‐segment elevation is a more specific diagnostic sign than the saddle‐type elevation because the latter has been reported in other conditions, including incomplete right bundle branch block, pectus excavatum, Chagas' disease, Steinert's disease, and mediastinal tumors. 29 The right bundle branch block pattern in Brugada syndrome is not typical of the classic right bundle branch block, and could be differentiated from it by distinct characteristics. First, in right bundle branch block, the S wave in the anterolateral leads (lead I, AVL, V5, and V6) is deep and wide, whereas in Brugada syndrome there is no deep wide S wave in these leads. Second, in right bundle branch block, the ST segment is usually either isoelectric or depressed in leads V1, V2, and V3 as a result of repolarization change secondary to the conduction block, whereas in Brugada syndrome the ST segment is elevated in these leads. Third, in right bundle branch block, the QRS complex is wide, the magnitude of width depends upon the severity of block, but in Brugada syndrome although the QRS appearance in the right precordial leads resembles the right bundle branch block, the QRS complex duration remains within normal limits.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram of Brugada syndrome characterized by right bundle branch type pattern with coving ST‐segment elevation in leads V1, V2,and V3.

The QT interval is not prolonged in Brugada syndrome. However, the PR and HV intervals could be prolonged. It is possible that Brugada syndrome patients who have prolonged PR or HV interval may share genetic resemblance with the Lenegre‐Lev disease, a disease caused by loss of function‐type mutations in the sodium channel. The long‐term follow‐up of these patients will clarify this issue because Lenegre‐Lev disease results in progressive degeneration of the conduction tissue that manifests at later ages. The possibility of a subclinical overlap between these diseases has been further strengthened by a recent observation by Shirai et al., 30 where a sodium channel disease with overlapping characteristics of Brugada syndrome and Lenegre‐Lev disease has been reported.

Patients with Brugada syndrome may not manifest the typical electrocardiographic pattern or may have a normal electrocardiogram. In addition, the Brugada syndrome electrocardiographic pattern is not persistent, and patients may only intermittently display characteristic electrocardiograms with normal electrocardiograms in between. Administration of Class IA and Class IC sodium channel blocking drugs increases the ST‐segment elevation in the right precordial leads in Brugada syndrome and predisposes the patient to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. 31 , 32 On the other hand, these agents shorten the repolarization phase and QT interval in patients with long QT‐3 syndrome, and, therefore, encompass beneficial effects in such patients. 33 In Brugada syndrome, fever, vagal stimulation, vagotonic drugs, bradycardia, alpha‐adrenergic agonists, beta‐adrenergic blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, and cocaine toxicity increase ST‐segment elevation, whereas adrenergic stimulation, tachycardia, and isoproterenol administration decrease or may even normalize ST segment elevation. 34 The heart rate acceleration decreases the ST‐segment elevation by restoring the action potential dome and reducing the notch. This happens because the Ito current is slow to recover from inactivation and, therefore, is less available at faster heart rates. Similarly, in long QT‐3 syndrome tachycardia shortens the QTc interval and decreases the chance of development of torsade de pointes and sudden cardiac death. In fact, cardiac pacing at higher rate than patient's heart rate is one of the therapies for long QT‐3 syndrome. Exercise decreases the ST‐segment elevation in Brugada syndrome or may even become isoelectric, and in long QT‐3 syndrome exercise decreases the QT interval that may become even super‐short.

Mexiletine, a class 1B sodium channel blocker, decreases the QT interval and dispersion of repolarization in long QT‐3 syndrome as well as in long QT‐1 and long QT‐2 syndromes by shortening the repolarization of M cells to a larger extent than that of subendocardial and subepicardial layers. Although mexiletine is a sodium channel blocker it does not have effect in Brugada syndrome because it inhibits the inactive state of the sodium channel. The Ito channel blocker 4‐aminopyridine decreases or abolishes ST‐segment elevation in Brugada syndrome but potassium channel openers increase ST‐segment elevation.

Among all the subtypes of long QT syndrome, the patients with long QT‐3 syndrome have the longest QTc interval. In a study on QT interval in different subtypes of the long QT syndrome, the QTc interval in patients with long QT‐3 syndrome was 510 ± 48 ms compared to 490 ± 43 ms in long QT‐1 and 495 ± 43 ms in long QT‐2 syndrome patients. 35 The ST segment remains essentially isoelectric in long QT‐3 syndrome, and the T wave is late appearing but is of high amplitude. The ST‐T wave changes of long QT‐3 syndrome may resemble that of a combined electrolyte disorder of hypocalcemia with moderate hyperkalemia. There is no conduction disturbance in long QT‐3 syndrome, although a repolarization‐dependent atrioventricular block may develop if the QTc interval is markedly prolonged. 8 A feature unique to long QT‐3 syndrome is the presence of sinus bradycardia and pauses, described in about half of the patients with long QT‐3 syndrome.

VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

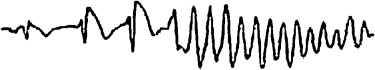

Symptoms in patients with Brugada syndrome are caused by rapid polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (Fig. 3) or ventricular fibrillation, although in rare cases it may be monomorphic. The ventricular tachycardia in Brugada syndrome is one of the non‐torsade type, usually non‐pause‐dependent and is usually faster than the torsade de pointes with a higher tendency to degenerate into ventricular fibrillation. However, ventricular fibrillation may occur without antecedent ventricular tachycardia. The arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome usually appear without warning, and are more prevalent during sleep. Fever has been shown to worsen the electrocardiographic pattern in Brugada syndrome and precipitate ventricular arrhythmias.

Figure 3.

Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in Brugada syndrome. The ST‐segment elevation worsened in successive beats preceding the initiation of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

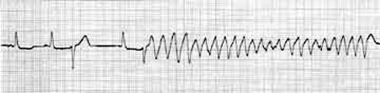

In long QT syndrome the polymorphic ventricular tachycardia is of torsade type (Fig. 4), usually pause‐dependent, characterized by a markedly prolonged QT interval in the last sinus beat preceding the onset of the arrhythmia, progressive twisting of the QRS complex polarity around an imaginary baseline, complete 180‐degree twist of the QRS complexes in 10 to 15 beats, changing amplitude of the QRS complexes in each cycle in a sinusoidal fashion, a heart rate between 150 and 300 beats/min, and irregular RR intervals. 36 The episodes of torsade de pointes in long QT‐3 syndrome, being bradycardia‐ or pause‐dependent, are most prevalent during sleep and rest. 37 Most of the torsade episodes are self‐limiting, but they could degenerate into ventricular fibrillation. Unlike Brugada syndrome, initiation of ventricular fibrillation without preceding polymorphic ventricular tachycardia has not been reported in patients with long QT‐3 syndrome. In familial catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, another electrical disease of the heart, there is a preceding acceleration in the heart rate before initiation of the ventricular tachycardia because polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in this condition is catecholamine‐dependent, which is not the case with Brugada syndrome or with long QT‐3 syndrome.

Figure 4.

Torsade de pointes initiating with a short‐long‐short cycle in the setting of prolonged QT interval.

In Brugada syndrome the tendency to develop ventricular tachycardia depends on the shortening of the action potential in the right ventricular subepicardial myocardium, whereas in long QT‐3 syndrome the relatively more prolonged repolarization of M cells in the middle myocardial layers results in lengthening of the QT interval and abnormalities in T and U waves providing a substrate for torsade de pointes.

SYMPTOMS

Clinically, both Brugada and long QT‐3 syndromes present with syncope, seizures, or sudden death. 38 In Brugada syndrome about 85% of the sudden death events occur during sleep or at rest, and in the long QT‐3 syndrome 60% of the sudden cardiac death events occur during sleep and at rest. 39 A higher incidence of sudden death during sleep in Brugada syndrome patients is due to bradycardia dependency, because the Ito current becomes more prominent at slow heart rate increasing the heterogeneity of refractiveness further between the subepicardial and subendocardial layers of the right ventricle. A higher incidence of sudden death during sleep in long QT‐3 syndrome is due to pauses and bradycardia; both can precipitate torsade de pointes due to higher early afterdepolarizations during prolonged repolarization. 39 Other triggers for symptoms in Brugada syndrome include fever, hyperglycemia, and the use of class IA and IC antiarrhythmic drugs, antimalarials, neuroleptics, antihistamines, antidepressants, and cocaine. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 About 60% of patients with symptomatic Brugada syndrome have a family history of sudden death or have family members with the electrocardiographic pattern of Brugada syndrome. Other patients (40%) have sporadic de novo mutations. About 10% of the patients with Brugada syndrome suffer from paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. 46 Therefore, palpitations in patients with Brugada syndrome could be due to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or the atrial fibrillation.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of both Brugada and long QT‐3 syndrome is made on the basis of clinical characteristics, electrocardiographic findings, and family history. 47 Unexplained syncope or sudden cardiac death in a family member, especially in a child or a young adult should raise a strong suspicion of the possibility of presence of a primary electrical disease of the heart in kindred. Genetic testing could be of help in borderline cases or in the cases where a new mutation is suspected, although it has not become a routine part of the diagnostic work up in Brugada or long QT‐3 syndromes. Pharmacological provocative testing for suspected Brugada syndrome could be done by administering a sodium channel blocker and the test is considered positive if an additional 1 mm ST‐segment elevation appears in precordial leads V1, V2, and V3. 48 Drugs that could be used for provocative testing include procainamide 10 mg/kg body weight intravenously in 10 minutes, flecainide 2 mg/kg body weight intravenously in 10 minutes, or ajmaline 1 mg/kg body weight intravenously in 5 minutes. Ajmaline is a better option for provocative testing because of its short half‐life that makes it safer, and its stronger sodium channel blocker effect that increases the sensitivity of the test. The magnitude of ST‐segment elevation with sodium channel blockers is inversely proportional to the rate of dissociation of the drug from the sodium channel. The sodium channel blocker provocative testing should be attempted only in a monitored environment.

The electrocardiographic criteria of Brugada syndrome include incomplete right bundle branch block pattern and ST‐segment elevation of equal to or more than 2 mm in precordial leads V1, V2, and V3 at baseline or after the administration of intravenous sodium channel blockers. The most powerful marker of cardiac arrest is the presence of spontaneous ST‐segment elevation in these leads combined with a history of syncope. It has been recently demonstrated that an electrocardiogram taken with precordial leads placed in higher intercostal spaces, with or without provocative testing, increases the detection rate in sudden unexplained death syndrome survivors and their relatives. 49 This is because the accentuation of action potential notch and loss of dome in subepicardium creating a voltage gradient between subepicardium and subendocardium may not be uniform throughout the right ventricle. Thus ST‐segment elevation depends on the position of the precordial electrodes relative to the specific site affected, which explains a high detection rate of higher placed precordial leads and right ventricular leads as compared to normal placed precordial leads because higher precordial leads and right ventricular leads will record electrical activity from right ventricular outflow tract and right ventricular free wall, respectively. 49 , 50 , 51

In symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome, ventricular tachycardia is inducible in about 80% of cases by one or two ventricular premature beats during programmed stimulation. The HV interval is prolonged in about half of the patients but rarely exceeds 70 ms. Prolongation of HV interval may explain the mild prolongation of PR interval reported in some cases of Brugada syndrome. Studies are conflicting regarding the association between inducibility of ventricular tachycardia and precipitation of life‐threatening events. For example, in one study, the electrophysiological evaluation failed to demonstrate an association between inducibility by programmed electrical stimulation and spontaneous occurrence of ventricular fibrillation with a specificity of only 34%, which was not different when two versus three premature stimuli were used. 52 On the other hand, in other studies inducibility of sustained ventricular tachycardia was a powerful predictor of arrhythmic events, both in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals of Brugada syndrome. 53 , 54 Among the noninvasive markers (late potentials, microvolt T‐wave alternans, QT dispersion), the presence of late potentials has the most significant correlation to the occurrence of life‐threatening events. 55 Torsade de pointes, on the other hand, is not inducible by programmed electrical stimulation.

TREATMENT

The antiarrhythmic drugs and beta‐receptor blockers do not protect against sudden cardiac death in Brugada syndrome. The only effective treatment available at this time for these patients is implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Beta‐blocker use, actually, increases the ST‐segment elevation in right precordial leads signaling worsening in the repolarization abnormality. It has been suggested that the symptomatic patients with Brugada syndrome should receive implantable cardioverter defibrillator to prevent sudden cardiac death. 55 Asymptomatic patients with an abnormal electrocardiogram and inducible polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation on programmed electrical stimulation may also benefit from implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Conversely, asymptomatic patients with an electrocardiogram abnormal only after drug challenge and no inducible ventricular tachycardia could be followed up carefully without implantable cardioverter defibrillator placement. Similarly, asymptomatic patients with spontaneous abnormal electrocardiogram, but noninducible polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and no family history of sudden cardiac death could also be followed carefully without implantable cardioverter defibrillator. On the other hand, the asymptomatic patients with spontaneously abnormal electrocardiogram and noninducible ventricular tachycardia but with a family history of sudden cardiac death could be offered implantable cardioverter defibrillator, although there are insufficient data to support this approach conclusively.

Repeated episodes of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (electrical storm) in Brugada syndrome could be treated temporarily with isoproterenol. An intriguing observation has been reported recently where oral administration of cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase III inhibitor, completely prevented episodes of ventricular fibrillation in a patient with Brugada syndrome. 56 This effect was confirmed by the on‐and‐off challenge test, in which discontinuation of the drug resulted in recurrence of ventricular fibrillation and resumption of the drug again prevented ventricular fibrillation. This effect may be related to the suppression of Ito secondary to the increase in heart rate or an increase in ICa due to an elevation of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate concentration via inhibition of phosphodiesterase activity. Experimental studies also suggest that Ito channel blockers such as quinidine, tedisamil, and 4‐aminopyridine may be useful in patients with Brugada syndrome. 57 , 58

In symptomatic patients with long QT‐3 syndrome where the torsade de pointes is bradycardia‐dependent or pause‐dependent, pacemaker is used to avoid bradycardia and pauses. 59 Pacing seems to be more effective in patients with long QT‐3, which is consistent with the observation that with increasing heart rates, long QT‐3 patients have a shorter QTc interval compared to long QT‐1 and long QT‐2 patients. 60 Pacemaker rates are set sufficient to normalize the QTc interval below 440 ms. Although the concept behind pacing preventing pause‐dependent arrhythmia is appealing, there are no long‐term data indicating that shortening QTc interval to 440 ms or less by pacing is truly protective in reducing morbidity and mortality. In asymptomatic patients with long QT‐3, the treatment modality is uncertain at this time, although those with bradycardia and a family history of sudden cardiac death theoretically might benefit from cardiac pacing at higher rates; however, no prospective data exist to support this presumption. Although beta‐adrenergic blockers are used in the chronic treatment of long QT syndrome in general, these agents are used with caution in patients with long QT‐3 syndrome, especially with resting bradycardia since further reduction in heart rate by beta‐adrenergic blockers theoretically may provoke torsade de pointes; however, more data seem required to substantiate this caution. 61

Experimental studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of mexiletine and flecainide in patients with long QT‐3 syndrome but caution should be used while using flecainide in these patients, as flecainide may induce ST‐segment elevation in leads V1 through V3 in long QT‐3 syndrome. 17 , 62 Mexiletine use might be considered in those long QT‐3 patients who remain symptomatic despite pacing and beta‐adrenergic blocker therapy; however, the efficacy of mexiletine therapy in long QT‐3 syndrome has not been tested in prospective trials. 63 , 64

An automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator is used in those patients with long QT‐3 syndrome who have survived aborted sudden death and who are symptomatic despite permanent pacemaker and maximum‐tolerated beta‐blockers. Considering the high lethality of a single episode of torsade de pointes in patients with long QT‐3 syndrome. 65 and the availability of a combined device of pacemaker with cardioverter defibrillator, there is increasing interest in using this device initially, although clinical data on implantable cardioverter defibrillator use in long QT‐3 patients are limited.

PROGNOSIS

According to recently reported data, the lifetime chances of having sudden cardiac death or documented ventricular fibrillation in Brugada syndrome are around 25%. 66 Recurrence of malignant arrhythmia is higher after the occurrence of symptoms. Asymptomatic patients and carriers with normal electrocardiogram in whom the electrocardiographic pattern becomes manifest only by sodium channel blocking drugs or who are noninducible on programmed stimulation have a relatively benign course. 55 Among asymptomatic individuals, those with a spontaneously abnormal electrocardiogram and inducible ventricular arrhythmias have poor prognosis. 67 Aborted sudden death, syncope, male gender, a family history of sudden death, spontaneously abnormal electrocardiogram, inducibility of ventricular tachyarrhythmias, and the presence of late potentials on signal average electrocardiogram have been reported as markers of life‐threatening events. 54 , 55 , 56 , 66 The annual mortality in Brugada syndrome ranges from 1% to 15% and that in long QT‐3 syndrome from 5% to 10%. Approximately, 20% of all cardiac events in long QT‐3 syndrome are fatal. Although patients with long QT‐3 syndrome have a less number of episodes of torsade de pointes compared to the patients with long QT‐1 and long QT‐2 syndromes, the lethality of an individual episode of torsade de pointes is higher in long QT‐3 syndrome. 34

REFERENCES

- 1. Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome: a multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20: 1391–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwartz PJ. The long QT syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol 1997;22: 297–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schott JJ, Alshinawi C, Kyndt F, et al Cardiac conduction defects associated with mutations in SCN5A. Nat Genet 1999;23: 20–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Brugada J, et al Brugada Syndrome: a Decade of Progress. Circ Res 2002;91: 1114–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. George AL Jr, Varkony TA, Drabkin HA, et al Assignment of the human heart tetrodotoxin‐resistant voltage‐gated Na+ channel alpha‐subunit gene (SCN5A) to band 3p21. Cytogenet Cell Genet 1995;68: 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gussak I, Antzelevitch C, Bjerregaard P, et al The Brugada syndrome: Clinical, electrophysiologic and genetic aspects. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33: 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weiss R, Barmada MM, Nguyen T, et al Clinical and molecular heterogeneity in the Brugada syndrome: A novel gene locus on chromosome 3. Circulation 2002;105: 707–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ravina T, Lapuerta JA, Brugada J. Prolonged repolarization in long QT3 syndrome: Unusual electrocardiographic findings. Int J Cardiol 2002;82: 71–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neyroud N, Tesson F, Denjoy I, et al A novel mutation in the potassium channel gene KVLQT1 causes the Jervell and Lange‐Nielson cardioauditory syndrome. Nat Genet 1997;15: 186–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Curran ME, Splawski I, Timothy KW, et al A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell 1995;80: 795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Splawski I, Tristani‐Firouzi M, Lehmann MH, et al Mutations in the hminK gene cause long QT syndrome and suppress IKs function. Nat Genet 1997;17: 338–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abbott GW, Sesti F, Splawski I, et al MiRP1 forms IKr potassium channels with HERG and is associated with cardiac arrhythmia. Cell 1999;97: 175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang Q, Shen J, Splawski I, et al SCN5A mutations associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome. Cell 1995;80: 805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khan IA. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of congenital and acquired long QT syndrome. Am J Med 2002;112: 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balser JR. The cardiac sodium channel: Gating function and molecular pharmacology. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2001;33: 599–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Naccarelli GV, Antzelevitch C. The Brugada syndrome: Clinical, genetic, cellular, and molecular abnormalities. Am J Med 2001;110: 573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, et al The elusive link between LQT3 and Brugada syndrome: The role of flecainide challenge. Circulation 2000;102: 945–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bezzina C, Veldkamp MW, Den Berg MP, et al A single Na(+) channel mutation causing both long‐QT and Brugada syndromes. Circ Res 1999;85: 1206–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Veldkamp MW, Viswanathan PC, Bezzina C, et al Two distinct congenital arrhythmias evoked by a multidysfunctional Na(+) channel. Circ Res 2000;86: E91–E97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsuo K, Akahoshi M, Nakashima E, et al The prevalence, incidence and prognostic value of the Brugada‐type electrocardiogram: A population‐based study of four decades. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38: 765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miyasaka Y, Tsuji H, Yamada K, et al Prevalence and mortality of the Brugada‐type electrocardiogram in one city in Japan. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38: 771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brugada J, Brugada P, Brugada R. Brugada syndrome: the syndrome of right bundle branch block, ST segment elevation in V1 to V3 and sudden death. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2001;1: 6–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Locati EH, Zareba W, Moss AJ, et al Age‐ and sex‐related differences in clinical manifestations in patients with congenital long‐QT syndrome: findings from the International LQTS Registry. Circulation 1998;97: 2237–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alings M, Wilde A. Brugada syndrome: clinical data and suggested pathophysiological mechanism. Circulation 1999;99: 666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nagase S, Kusano KF, Morita H, et al Epicardial electrogram of the right ventricular outflow tract in patients with the Brugada syndrome: using the epicardial lead. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39: 1992–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Ambroggi L, Negroni MS, Monza E, et al Dispersion of ventricular repolarization in the long QT syndrome. Am J Cardiol 1991;68: 614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Day CP, McComb JM, Campbell RW. QT dispersion: an indication of arrhythmia risk in patients with long QT intervals. Br Heart J 1990;63: 342–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Viskin S, Alla SR, Barron HV, et al Mode of onset of torsade de pointes in congenital long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28: 1262–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brugada P, Brugada J, Brugada R. Dealing with biological variation in the Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J 2001;22: 2231–2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shirai N, Makita N, Sasaki K, et al A mutant cardiac sodium channel with multiple biophysical defects associated with overlapping clinical features of Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction disease. Cardiovasc Res 2002;53: 348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fujiki A, Usui M, Nagasawa H, et al ST segment elevation in the right precordial leads induced with class IC antiarrhythmic drugs: Insight into the mechanism of Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1999;10: 214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C, Suyama K, et al Effect of sodium channel blockers on ST segment, QRS duration, and corrected QT interval in patients with Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2000;11: 1320–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Locati EH, et al Long QT syndrome patients with mutations of the SCN5A and HERG genes have differential responses to Na channel blockade and to increases in heart rate: Implications for gene specific therapy. Circulation 1995;92: 3381–3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miyazaki T, Mitamura H, Miyoshi S, et al Autonomic and antiarrhythmic drug modulation of ST segment elevation in patients with Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27: 1061–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zareba W, Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ, et al Influence of genotype on the clinical course of the long‐QT syndrome. N Engl J Med 1998;339: 960–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khan IA. Twelve‐lead electrocardiogram of torsades de pointes. Tex Heart Inst J 2001;28: 69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Viskin S, Alla SR, Barron HV, et al Mode of onset of torsade de pointes in congenital long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28: 1262–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vincent GM, Timothy KW, Leppert M, et al The spectrum of symptoms and QT intervals in carriers of the gene for the long‐QT syndrome. N Eng J Med 1992;327: 846–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, et al Genotype‐phenotype correlation in the long‐QT syndrome: gene‐specific triggers for life‐threatening arrhythmias. Circulation 2001;103: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tada H, Sticherling C, Oral H, et al Brugada syndrome mimicked by tricyclic antidepressant overdose. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2001;12: 275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goldgran‐Toledano D, Sideris G, Kevorkian JP. Overdose of cyclic antidepressants and the Brugada syndrome. N Engl J Med 2002;346: 1591–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pastor A, Nunez A, Cantale C, et al Asymptomatic Brugada syndrome case unmasked during dimenhydrinate infusion. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2001;12: 1192–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rouleau F, Asfar P, Boulet S, et al Transient ST segment elevation in right precordial leads induced by psychotropic drugs: Relationship to the Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2001;12: 61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ortega‐Carnicer J, Bertos‐Polo J, Gutierrez‐Tirado C. Aborted sudden death, transient Brugada pattern, and wide QRS dysrrhythmias after massive cocaine ingestion. J Electrocardiol 2001;34: 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Littmann L, Monroe MH, Svenson RH. Brugada‐type electrocardiographic pattern induced by cocaine. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75: 845–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eckardt L, Kirchhof P, Loh P, et al Brugada syndrome and supraventricular tachyarrhythmias: A novel association J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2001;12: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Khan IA. Long QT syndrome: Diagnosis and management. Am Heart J 2002;143: 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brugada R. Use of intravenous antiarrhythmics to identify concealed Brugada syndrome. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med 2000;1: 45–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sangwatanaroj S, Prechawat S, Sunsaneewitayakul B, et al New electrocardiographic leads and the procainamide test for the detection of the Brugada sign in sudden unexplained death syndrome survivors and their relatives. Eur Heart J 2001;22: 2290–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shimizu W, Matsuo K, Takagi M, et al Body surface distribution and response to drugs of ST segment elevation in Brugada syndrome: clinical implication of eighty‐seven‐lead body surface potential mapping and its application to twelve‐lead electrocardiograms. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2000;11: 396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sangwatanaroj S, Prechawat S, Sunsaneewitayakul B, et al Right ventricular electrocardiographic leads for detection of Brugada syndrome in sudden unexplained death syndrome survivors and their relatives. Clin Cardiol 2001;24: 776–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M, et al Natural history of Brugada syndrome: Insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation 2002;105: 1342–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brugada P, Geelen P, Brugada R, et al Prognostic value of electrophysiologic investigations in Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2001;12: 1004–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brugada J, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C, et al Long‐term follow‐up of individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of right bundle‐branch block and ST‐segment elevation in precordial leads V1 to V3. Circulation 2002;105: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ikeda T, Sakurada H, Sakabe K, et al Assessment of noninvasive markers in identifying patients at risk in the Brugada syndrome: Insight into risk stratification. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37: 1628–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tsuchiya T, Ashikaga K, Honda T, et al Prevention of ventricular fibrillation by cilostazol, an oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor, in a patient with Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2002;13: 698–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Belhassen B, Viskin S, Fish R, et al Effects of electrophysiologic‐guided therapy with Class IA antiarrhythmic drugs on the long‐term outcome of patients with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation with or without the Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1999;10: 1301–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alings M, Dekker L, Sadee A, et al Quinidine induced electrocardiographic normalization in two patients with Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2001;24: 1420–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Viskin S, Glikson M, Fish R, et al Rate smoothing with cardiac pacing for preventing torsade de pointes. Am J Cardiol 2000;86: K111–K115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Cantu F, et al Differential response to Na+ channel blockade, beta‐adrenergic stimulation, and rapid pacing in a cellular model mimicking the SCN5A and HERG defects present in the long‐QT syndrome. Circ Res 1996;78: 1009–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Locati EH, et al Long QT syndrome patients with mutations of the SCN5A and HERG genes have differential responses to Na+ channel blockade and to increases in heart rate. Implications for gene‐specific therapy. Circulation 1995;92: 3381–3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Benhorin J, Taub R, Goldmit M, et al Effect of flecainide in patients with new SCN5A mutation: Mutation specific therapy for long QT syndrome. Circulation 2000;101: 1698–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang DW, Yazawa K, Makita N, et al Pharmacological targeting of long QT mutant sodium channels. J Clin Invest 1997;99: 1714–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Sodium channel block with mexiletine is effective in reducing dispersion of repolarization and preventing torsade des pointes in LQT2 and LQT3 models of the long‐QT syndrome. Circulation 1997;96: 2038–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zareba W, Moss AJ, Locati EH, et al Modulating effects of age and gender on the clinical course of long QT syndrome by genotype. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Natural history in patients with Brugada syndrome. First Virtual Symposium About the Brugada Syndrome. November 130, 2002; http://www.brugada-symposium.org.

- 67. Ikeda T. Brugada syndrome: current clinical aspects and risk stratification. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2002;7: 251–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]