Abstract

Background: Cigarette smoking increases the risk of cardiovascular events related with several mechanisms. The most suggested mechanism is increased activity of sympathetic nervous system. Heart rate variability (HRV) and heart rate turbulence (HRT) has been shown to be independent and powerful predictors of mortality in a specific group of cardiac patients. The goal of this study was to assess the effect of heavy cigarette smoking on cardiac autonomic function using HRV and HRT analyses.

Methods: Heavy cigarette smoking was defined as more than 20 cigarettes smoked per day. Heavy cigarette smokers, 69 subjects and nonsmokers 74 subjects (control group) were enrolled in this study. HRV and HRT analyses [turbulence onset (TO) and turbulence slope (TS)] were assessed from 24‐hour Holter recordings.

Results: The values of TO were significantly higher in heavy cigarette smokers than control group (−1.150 ± 4.007 vs −2.454 ± 2.796, P = 0.025, respectively), but values of TS were not statistically different between two groups (10.352 ± 7.670 vs 9.613 ± 7.245, P = 0.555, respectively). Also, the number of patients who had abnormal TO was significantly higher in heavy cigarette smokers than control group (23 vs 10, P = 0.006). TO was correlated with the number of cigarettes smoked per day (r = 0.235, P = 0.004). While LF and LF/HF ratio were significantly higher, standard deviation of all NN intervals (SDNN), standard deviation of the 5‐minute mean RR intervals (SDANN), root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), and high‐frequency (HF) values were significantly lower in heavy smokers. While, there was significant correlation between TO and SDNN, SDANN, RMSSD, LF, and high frequency (HF), only HF was correlated with TS.

Conclusion: Heavy cigarette smoking has negative effect on autonomic function. HRT is an appropriate noninvasive method to evaluate the effect of cigarette on autonomic function. Simultaneous abnormal HRT and HRV values may explain increased cardiovascular event risk in heavy cigarette smokers.

Keywords: heart rate turbulence, cigarette

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking is a major cardiovascular risk factor. Smoking may lead to myocardial infarction, stroke, and sudden death by several mechanisms. 1 Smoking increases sudden death risk more than tenfold in men and fivefold in women. 2 Increased sympathetic nervous system activity is one of the factors suggested to be responsible for the effects of smoking. 3 However, previous studies that used heart rate variability (HRV) showed conflicting results about the effect of cigarette on autonomic nervous system. 4 , 5 Heart rate turbulence (HRT) is a novel noninvasive method to assess autonomic function. HRT has been shown to be a greater predictive power than HRV on mortality. 6 No studies have previously evaluated HRT analysis in heavy cigarette smokers. Therefore, the goal of this study was to assess the effect of heavy cigarette smoking on cardiac autonomic function using HRV and HRT analyses and to determine the association between HRT and HRV parameters.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Group

This study was performed in Ministry of Health Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Research and Educational Hospital and Yuksek Ihtisas Heart‐Education and Research Hospital from June 2007 to May 2008. A total of 4875 Holter recordings were evaluated for ventricular premature beat presence. For the measurement of HRT parameters during echocardiography, recordings having at least 500 ventricular premature complex (VPCs)/day were chosen for the evaluation. However, after removal of patients with exclusion criteria, only 143 subjects were included in the study. Therefore, 69 healthy long‐term heavy smokers (41 females, 28 males, with mean age of 42.36 ± 7.84 years) and age‐ and sex‐matched 74 nonsmokers (50 females, 28 males, with age of 41.38 ± 8.65 years) were enrolled in the study. Heavy cigarette smoking was defined as more than 20 cigarettes smoked per day.

The subjects who had hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, valvular heart diseases or other structural heart disease, lung diseases and/or pulmonary HT, renal diseases, collagen diseases, rhythms other than sinus, abnormal thyroid function, or serum electrolyte values were excluded from the study. In addition, subjects who had not any VPC to measure HRT were excluded from the study. Also, the subjects who use drugs that may influence HRT parameters were excluded from the study. All subjects were not allowed to drink alcohol and any caffeinated beverages during the study.

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed using Vingmed Vivid 3 (Horten, Norway) echocardiograph and a 2.5 MHz transducer to determine underlying structural heart disease before the study.

A written consent was obtained from all patients and our local ethical committee approved the study.

HRT Analysis

All subjects underwent 24‐hour Holter monitoring. Holter ECGs were carefully analyzed by expert cardiologists blinded to the study using DMS CardioScan Holter system (DM Soft‐ware., Inc., Stateline, NV, USA). HRT parameters were calculated using an algorithm adapted from the web page popularizing noncommercial use of HRT (http://www.h-r-t.org). In HRT analysis, two numerical descriptors were estimated: TO and TS. TO is the amount of sinus acceleration following a VPC, TS is the rate of sinus deceleration that follows the sinus acceleration. TO is expressed as a percentage and is calculated with the following formula: TO (%) = 100 ×[(RR1+ RR2) − (RR−1+ RR−2)]/(RR−1+ RR−2), where RR1 and RR2 are the first and second sinus RR intervals after the VPC, and RR−1 and RR−2 are the first and second sinus intervals preceding the VPC. TS was calculated as the maximum positive slope of a regression line assessed over any sequence of five subsequent sinus‐rhythm RR intervals within the first 20 sinus‐rhythm intervals after a VPC. TS was calculated based on the averaged tachogram. Filtering algorithms were used to eliminate inappropriate RR intervals and VPCs with overly long coupling intervals or overly short compensatory pauses. Filtering algorithms excluded from the HRT calculation RR intervals with the following characteristics: <300 ms, >2000 ms, >200 ms difference to the preceding sinus interval, and >20% difference to the reference interval (mean of the five last sinus intervals). In addition, these algorithms limit the HRT calculation to VPCs with a minimum prematurity of 20% and a postextrasystole interval that is at least 20% longer than the reference interval (mean of last five sinus RR intervals). TO ≥0% and TS ≤ 2.5 ms/beat are described as abnormal.

HRV Analysis

The HRV analysis was assessed over a 24‐hour period. The time‐ and frequency‐domain analyses of HRV were performed according to the recommendation of the task force. 7 For the time domain, standard deviation of all NN intervals (SDNN), standard deviation of the 5‐minute mean RR intervals (SDANN), and root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) were measured. For the frequency domain, analysis power spectral analysis based on the Fast Fourier transformation algorithm was used. Three components of power spectrum were computed following bandwidths: HF (0.15–0.4 Hz), LF (0.04–0.15 Hz), and the LF/HF ratio.

Statistical Analysis

Results were reported as mean ± standard deviation and percentages. Continuous variables were analyzed with Student's t‐test. Categorical variables were compared by using chi‐square test. The relation between the number of years of smoking and the number of cigarettes smoked per day and HRT parameters were assessed by Pearson's correlation coefficient. Also, association between HRV and HRT parameters were assessed by Pearson's correlation coefficient. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS‐15.0 for Windows statistical software package program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

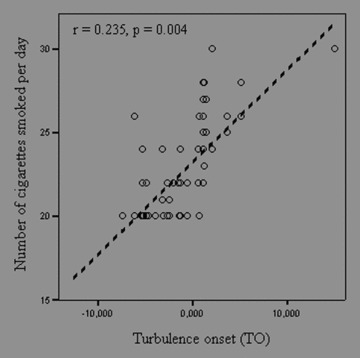

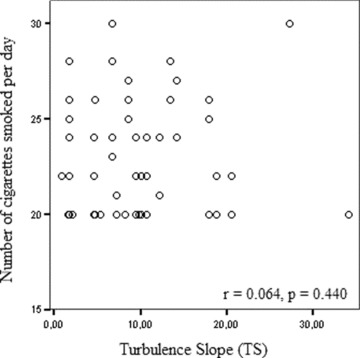

Clinical characteristics of two groups were shown in Table 1. Age, sex, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, left ventricular ejection fraction, mean heart rate, and mean ventricular premature contraction were not significantly different between two groups. The results of the HRT parameters were shown in Table 2. The values of TO were significantly higher in heavy smokers group than control group (−1.150 ± 4.007 vs −2.454 ± 2.796, P = 0.025, respectively), but values of turbulence (TS) were not statistically different between two groups (10.352 ± 7.670 vs 9.613 ± 7.245, P = 0.555, respectively). When value >0% for TO and <2.5 ms/beat for TS, proposed by Schmidt et al., 6 was used as abnormal HRT values, the number of subjects who had abnormal TO was significantly higher in heavy smokers group than control group (23 vs 10, P = 0.006). However, the number of subjects who had abnormal TS was not different in both groups. Correlation analyses revealed a significant association between TO and the number of cigarettes smoked per day (r = 0.235, P = 0.004) (Fig. 1). But, there was no correlation between TS and the number of cigarettes smoked per day (Fig. 2). Also, no correlation was found between the duration of cigarette smoking and each HRT parameters.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Study Subjects

| Heavy Smokers Group | Control Group | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.36 ± 7.84 | 41.38 ± 8.65 | 0.468 |

| Men, n (%) | 28 (37.8%) | 24 (32.4%) | 0.491 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.27 ± 2.54 | 24.73 ± 2.20 | 0.169 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 128.24 ± 16.85 | 126.35 ± 14.00 | 0.459 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 79.53 ± 9.62 | 78.31 ± 5.63 | 0.350 |

| Cigarettes/day | 22.40 ± 2.94 | – | |

| Duration of smoking (years) | 8.80 ± 2.93 | – | |

| Left ventricular EF (%) | 64.41 ± 6.75 | 64.08 ± 4.98 | 0.740 |

| Mean heart rate (beats/min) | 77.76 ± 7.17 | 76.01 ± 9.02 | 0.195 |

| Ventricular premature contraction/day | 782.03 ± 1827.41 | 808.46 ± 1323.58 | 0.920 |

BP = blood pressure; EF = ejection fraction.

Table 2.

Results of Heart Rate Turbulence (HRT) Analyses

| Heavy Smokers Group | Control Group | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TO (%) | −1.15 ± 4.01 | −2.45 ± 2.80 | 0.025 |

| TS (ms/beat) | 10.35 ± 7.67 | 9.61 ± 7.24 | 0.555 |

| Abnormal TO, n (%) | 23 (33) | 10 (14) | 0.006 |

| Abnormal TS, n (%) | 12 (17) | 10 (14) | 0.521 |

TO = turbulence onset; TS = turbulence slope.

Figure 1.

Correlation between turbulence onset (TO) and the number of cigarette smoked per day.

Figure 2.

Correlation between turbulence slope and the number of cigarette smoked per day.

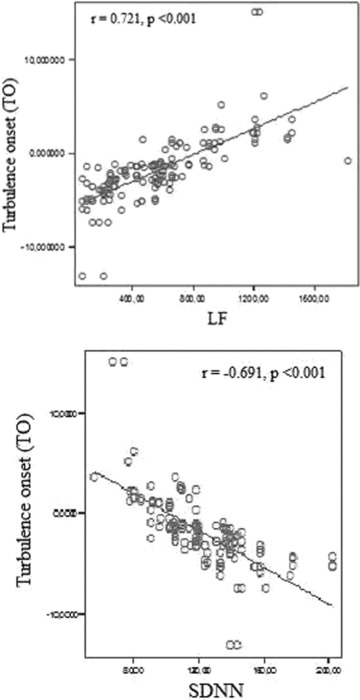

The results of the HRV parameters were shown in Table 3. While LF and LF/HF ratio were significantly higher, SDNN, SDANN, RMSSD and HF values were significantly lower in heavy smokers. While, there was significant correlation between TO and SDNN, SDANN, RMSSD, LF, and HF, only HF was correlated with TS. (Table 4, Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Results of Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Parameters

| Heavy Smokers Group | Control Group | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDNN (ms) | 108.7 ± 22.5 | 133.4 ± 24.2 | <0.001 |

| SDANN (ms) | 99.2 ± 20.3 | 121.4 ± 23.5 | <0.001 |

| RMSSD (ms) | 28.4 ± 16.3 | 42.4 ± 14.2 | <0.001 |

| LF (ms2) | 691.0 ± 362.0 | 441.5 ± 310.1 | <0.001 |

| HF (ms2) | 140.2 ± 95.4 | 261.0 ± 223.3 | <0.001 |

| LF/HF | 5.5 ± 1.9 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

SDNN = standard deviation of all NN intervals; SDANN = standard deviation of the 5‐minute mean RR intervals; RMSSD = root mean square of successive differences; LF = low frequency; HF = high frequency.

Table 4.

Correlation between HRT and HRV Parameters

| HRV Parameters | Turbulence Onset | Turbulence Slope |

|---|---|---|

| SDNN | r =−0.691, P < 0.001 | r = 0.090, P = 0.285 |

| SDANN | r =−0.658, P < 0.001 | r = 0.100, P = 0.235 |

| RMSSD | r =−0.220, P = 0.008 | r = 0.027, P = 0.746 |

| LF | r = 0.721, P < 0.001 | r =−0.118, P = 0.161 |

| HF | r =−0.436, P < 0.001 | r = 0.241, P = 0.004 |

SDNN = standard deviation of all NN intervals; SDANN = standard deviation of the 5‐minute mean RR intervals; RMSSD = root mean square of successive differences; LF = low frequency; HF = high frequency.

Figure 3.

Relationship between TO and LF (upper panel) and SDNN (lower panel).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effect of cigarette smoking on cardiac autonomic function by HRT analyses. In our study, we found that mean TO values and the number of subjects who had abnormal TO were significantly different in heavy smoker subjects from controls. The numbers of cigarettes smoked per day were positively correlated with TO values. In addition, cigarette smoking causes an increase in LF and LF/HF ratio, while a decrease in SDNN, SDANN, RMSSD, and HF. Also, it was observed that, TO was significantly correlated with SDNN, SDANN, RMSSD, LF and HF, but only HF was correlated with TS.

Cigarette smoking is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease. There are several mechanisms suggested about hazardous effects of smoking on cardiovascular events. One of these suggested mechanisms is a smoking‐initiated activation of the sympathetic nervous system. 3 Hayano et al. have demonstrated that smoking causes an acute and transient decrease in vagal cardiac control, and that heavy smoking causes long‐term reduction in vagal cardiac control and blunted postural responses in autonomic cardiac regulation. 8 Alyan et al. have showed that smoking causes a significant increase in sympathetic activity and impairs sympathovagal balance. 9 Previous studies that evaluated the effect of smoking on cardiac autonomic function, usually used HRV analysis. 4 , 5 , 9 , 10 , 11 Conflicting results have been reported in these studies. 4 , 5 Kageyama et al. showed that smoking was not associated with HRV parameters. 4 In contrast, Eryonucu et al. found that HRV parameters were significantly lower in smokers than in nonsmokers. 5 Therefore, we used HRT analysis to investigate the effect of smoking on autonomic function.

HRT is a marker of autonomic function, defined as initial acceleration and a subsequent deceleration of sinus rhythm following a ventricular premature complex. HRT is relatively new noninvasive test and is considered to reflect increased sympathetic tone and abnormal baroreflex sensitivity. 12 , 13 First in 1999, Schmidt et al. introduced HRT, since than HRT has been used to assess autonomic function and to predict sudden death in different patient groups. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Barthel et al. demonstrated that HRT was a strong predictor of subsequent death in postinfarction patients of the reperfusion era. 14 Also, HRT has been shown to be an independent and powerful predictor of mortality after myocardial infarction, with greater predictive power than HRV. 6 Jeron et al. showed that HRT was blunted in diabetic patients with autonomic dysfunction. 15 Cryer et al. have reported that plasma catecholamine levels increase within 1 minute after smoking. 20 Also, in a previous study in which HRV was used, LF/HF ratio significantly increased immediately after smoking. 21 In our study, there was a significant positive correlation between TO values and the number of cigarettes smoked per day. This finding could show acute effect of smoking on autonomic cardiac function.

In the present study, impaired HRV was also demonstrated in heavy smokers. This data suggests that sympathetic activation during cigarette smoking may be result of increased catecholamine in plasma or impaired baroreflex function. Previous studies showed that, there was a correlation between HRT and HRV parameters in a different group of cardiac patients. 13 , 22 , 23 Lindgren et al. demonstrated that TO and TS correlated with baroreflex sensitivity. In that study, TS correlated with SDNN, while only LF/HF was correlated with TS. 22 Koyoma et al. showed that, TO and TS significantly correlated with SDNN in chronic heart failure patients. 23 Also, in patients with coronary heart disease, the significant correlation between HRT and HRV parameters was observed. 13 Similarly, in our study, there was significant correlation between TO and HRV parameters. The results of this study indicate that HRT is not only related with abnormal baroreflex sensitivity, also is related with autonomic tone.

Study Limitations

These preliminary findings require confirmation in larger number of heavy cigarette smokers. HRT cannot be measured in subjects without VPCs, as a minimum of 15–20 sinus beats after each VPC and 3–5 beats before the VPC are required for accurate calculation of HRT. 6 Therefore, we had to exclude the subjects, who did not have any VPC, in this study. Circadian variation can influence HRT results. We could not examine circadian pattern of HRT values and mean RR intervals. In addition, it is difficult to accept that these subjects represent fully healthy cohort. Therefore generalization of our results to entire healthy population is a difficult concern.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, heavy cigarette smoking has negative effect on autonomic function. HRT is an appropriate noninvasive method to evaluate effect of cigarette on autonomic function. Simultaneous abnormal HRT and HRV values may explain increased cardiovascular event risk in heavy cigarette smokers.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hallstrom AP, Cobb LA, Ray R. Smoking as a risk factor for recurrence of sudden cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 1986;314:271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kannel WB, McGee DL, Castelli WP. Latest perspectives on cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: The Framingham study. J Cardiac Rehabil 1984;4:267–277. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hering D, Somers VK, Kara T, et al Sympathetic neural responses to smoking are age dependent. J Hypertens 2006;24:691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kageyama T, Nishikido N, Honda Y, et al Effect of obesity, current smoking status, and alcohol consumption on heart rate variability in male white‐collar workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1997;69:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eryonucu B, Bilge M, Guler N, et al Effect of cigarette smoking on the circadian rhythm of heart rate variability. Acta Cardiol 2000;55:301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmidt G, Malik M, Barthel P, et al Heart rate turbulence after ventricular premature beats as a predictor of mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1999;353:1390–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology . Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayano J, Yamada M, Sakakibara Y, et al Short‐ and long‐term effect of cigarette smoking on heart rate variability. Am J Cardiol 1990;65:84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alyan O, Kacmaz F, Ozdemir O, et al Effect of cigarette smoking on heart rate variability and plasma N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide in healty subjects: Is there the relationship between both markers? ANE 2008;13:137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barutcu I, Esen AM, Kaya D, et al Cigarette smoking and heart rate variability: Dynamic influence of parasympathetic and sympathetic maneuvers. ANE 2005;10:324–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levin FR, Levin HR, Nagoshi C. Autonomic functioning and cigarette smoking: Heart rate spectral analysis. Biol Physchiatry 1992;31:639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Watanabe MA, Marine JE, Sheldon R, et al Effects of ventricular premature stimulus coupling interval on blood pressure and heart rate turbulence. Circulation 2002;106:325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cygankiewicz I, Wranicz J, Bolinska H, et al Relationship between heart rate turbulence and heart rate, heart rate variability, and number of ventricular premature beats in coronary patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2004;15:731–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barthel P, Schneider R, Bauer A, et al Risk stratification after acute myocardial infarction by heart rate turbulence. Circulation 2003;108:1221–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jeron A, Kaiser T, Hengstenberg C, et al Association of the heart rate turbulence with classic risk stratification parameters in postmyocardial infarction patients. ANE 2003;8:296–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iwasa A, Hwa M, Hassankhani A, et al Abnormal heart rate turbulence predicts the initiation of ventricular arrhythmias. PACE 2005;28:1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cygankiewicz I, Zareba W, Vazquez R, et al Relation of heart rate turbulence to severity of heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:1635–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sestito A, Valsecchi S, Infusino F, et al Differences in heart rate turbulence between patients with coronary artery disease and patients with ventricular arrhythmias but structurally normal hearts. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:1114–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gunduz H, Arinc H, Kayardi M, et al Heart rate turbulence and heart rate variability in patients with mitral valve prolapse. Europace 2006;8:515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cryer PE, Haymond MW, Santiago JV, et al Norepinephrine release and adrenergic mediation of smoking‐associated hemodynamic and metabolic events. N Engl J Med 1976;295:573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kobayashi F, Watanabe T, Akamatsu Y, et al Acute effects of cigarette smoking on the heart rate variability of taxi drivers during work. Scand J Work Environ Health 2005;31:360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindgren KS, Makikallio TH, Seppanen T, et al Heart rate turbulence after ventricular and atrial premature beats in subjects without structural heart disease. J Clin Electrophysiol 2003;14:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koyama J, Watanabe J, Yamada A, et al Evaluation of heart‐rate turbulence as a new prognostic marker in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 2002;66:902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]