Abstract

Background: Inflammation plays a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Attempts are made to use markers of inflammation as prognostic factors in coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes. The correlation between inflammation and silent postinfarction ischemia is unknown.

Methods: The study population consists of 104 asymptomatic patients who had uncomplicated Q‐wave myocardial infarction within 6 months prior to the enrollment. After the white blood cell (WBC) count was assessed, the population was divided into two groups: group I comprising 48 patients with WBC ≤ 7.0 × 103/μl and group II comprising 56 patients with WBC > 7.0 × 103/μl. Twenty‐four‐hour Holter monitoring was performed to detect the presence of silent ischemia.

Results: Eighty‐eight silent ischemic episodes were recorded. Ischemia on Holter monitoring was detected in 47 patients (84%) from group II and in five patients (9%) in group I (P < 0.01). We have found a significant positive correlation between WBC count and the number of ischemic episodes (r = 0.25), their maximal amplitude (r = 0.39), duration (r = 0.34), and total ischemic burden (r = 0.36). In multivariate analysis leucocytosis proved to be the only parameter independently correlated with the presence of silent ischemia.

Conclusion: Postinfarction asymptomatic patients with increased WBC count are more likely to have residual ischemia.

Keywords: white blood cell count, silent ischemia, myocardial infarction

A number of recent experimental and clinical studies have indicated that inflammation plays a prominent role in the progression of atherosclerosis. Researchers have sought to identify inflammatory markers that might improve our ability to assess the risk and prognosis of patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS).

It is not clear whether silent ischemia is associated with inflammatory reactions and whether they could be detected.

It is known that the prognosis of patients with silent ischemia after myocardial infarction (MI) is at least as unfavorable as those with symptomatic ischemia. However, all previous reports, linking markers of inflammation (C‐reactive protein, leucocyte count, cytokines, intercellular adhesion molecules) with exacerbation of myocardial ischemia, investigated only the symptomatic coronary artery disease (CAD).

The aim of our study was to assess the relation between leucocyte count, a simple, sensitive marker of inflammation, and the occurrence of silent ischemia in patients after myocardial infarction.

METHODS

Asymptomatic patients who had Q‐wave myocardial infarction 3–6 months prior to the enrollment were included in the study, if they fulfilled the following criteria:

-

1

Negative result of predischarge submaximal exercise test.

-

2

Lack of chest pain during the postinfarction period.

-

3

Lack of concomitant diseases that might have increased leucocytosis (e.g. connective tissue diseases, neoplasmatic diseases).

-

4

Absence of acute infections 30 days prior to the study.

-

5

Lack of concomitant conditions that might preclude the interpretation of ST‐segment changes (e.g. branch bundle blocks, artificial pacemaker, signs of pre‐excitation).

-

6

Absence of ST‐segment changes in standard rest 12‐lead ECG or in Holter monitoring during hyperventilation or any postural maneuvers.

Blood cell count was assessed two times in a week in all patients. The white blood cell (WBC) count was performed by an automated cell counter SYSMEX 4500. Blood samples were taken in the morning, after an overnight fast. The mean of the two WBC count values was calculated for each patient and used in the analysis. The cut‐off values of WBC count used to dichotomize the study groups were determined based on available reports from other patient populations. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 The values above which evidence of substantial inflammation was considered to exist, were WBC > 7.0 × 103/μl versus ≤7.0 × 103/μl.

To detect the presence of silent ischemia ambulatory ECG monitoring was performed. All patients underwent 24‐hour Holter monitoring using three‐channel recorders Oxford Medilog 4500‐3. Placement of high‐quality pre‐gelled electrodes was chosen to obtain registration from modified precordial leads: V5 on channel 1, V1 on channel 2, and lead III on channel 3. Before each recording, the patients adopted supine, right lateral, prone, left lateral, and standing positions, and underwent a period of hyperventilation (each maneuver for 30 seconds). Patients observed with ST‐segment shifts during this procedure were not included (see above). The magnetic audiotapes (TDK AD 60) were analyzed using a computerized system Medilog Excel‐2, Oxford Medical. Episodes classified by the system as ST‐segment shifts were verified by visual “step‐by‐step” analysis. A transient ischemic episode was defined as horizontal or downsloping ST‐segment depression of at least 1 mm measured 80 ms after the J‐point, lasting for at least 1 minute. Episodes were considered to be separate if the ST‐segment depression was absent for at least 1 minute.

Statistical Analysis

Mean value ± SD was calculated for all variables. The verification of data distribution was done using the Shapiro‐Wilks test. Differences in the assessed parameters between the study groups were examined by Kolmogorow‐Smirnow test for two independent samples. To estimate the power of the relation between WBC and the parameters of ischemic episodes the Spearman's correlation rank coefficient was obtained. A multivariate discriminant analysis examined the relative predictive value of the variables considered to have clinically relevant association with the presence of silent ischemia. A P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. The software used was STATISTICA 5.1.

RESULTS

Hundred and four patients of mean age 56 ± 9.6 years (range 38–74) fulfilled the entry criteria and were included in the study. Most of them were men (84 vs 20 women). Sixty‐seven patients had inferior myocardial infarction and the remaining 37 had anterior myocardial infarction. All patients received thrombolytic therapy during the acute phase of infarction (97‐tPA, 14‐streptokinase). Following the postinfarction period, patients were on standard pharmacological treatment (aspirin, nitrates, beta‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, statins).

Based on the WBC count values patients were divided into two groups. Group I comprised 48 individuals with WBC ≤ 7.0 × 103/μl. The remaining 56 patients with mean WBC > 7.0 × 103/μl constituted group II. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups according to demographic data, risk factors, left ventricular function, and treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Groups Characteristics

| Parameter | Group I | Group II | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 48 | 56 | – |

| Female/Male | 8/40 | 12/44 | NS |

| Age | 58 ± 8.6 | 57 ± 8.3 | NS |

| Localization of MI anterior/inferior | 18/30 | 19/37 | NS |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 45 ± 6.8 | 45 ± 6.8 | NS |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 28 | 32 | NS |

| Arterial hypertension | 22 | 27 | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 | 11 | NS |

| Smoking | 35 | 37 | NS |

| Family history | 25 | 26 | NS |

The mean WBC count value in group I was 6.14 ± 0.56 × 103/μl and in group II was 9.01 ± 0.89 × 103/μl (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Medical therapy during Holter monitoring is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular Treatment During Holter Monitoring

| Medication | Group I | Group II | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrates | 10 (21%) | 14 (25%) | NS |

| Beta‐Blockers | 41 (88%) | 50 (89%) | NS |

| Ca‐antagonists | 6 (13%) | 6 (11%) | NS |

| ACEI | 38 (79%) | 46 (82%) | NS |

| Statin | 28 (58%) | 32 (57%) | NS |

| Aspirin | 48 (100%) | 56 (100%) | NS |

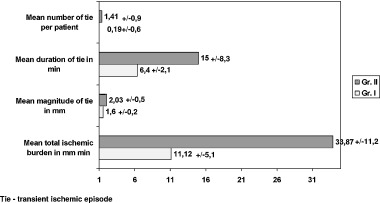

Eighty‐eight transient ischemic episodes were recorded from 24‐hour ECG monitoring. Nine of them (10%) occurred in group I and 79 (90%) in group II (P < 0.001). All episodes were silent. On Holter monitoring ischemia was detected in 47 patients (84%) in group II and in five patients (9%) in group I (P < 0.01). Transient ischemic episodes recorded in group II were significantly longer and had a greater magnitude of ST‐segment depression than those detected in group I (Fig. 2). For each individual the total ischemic burden was calculated as the sum of the products of the duration and amplitude of an episode, for all episodes detected in each patient. The mean total ischemic burden in group I (11.12 ± 5.10) was significantly lower than that in group II (33.87 ± 11.20) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of ischemic episodes in study groups.

A significant correlation was found between the WBC count values and the duration of transient ischemic episodes (correlation ratio r = 0.34, P < 0.001), the maximal amplitude of episode (r = 0.39, P < 0.001), the number of episodes that occurred during 24 hours (r = 0.25, P < 0.01), and the total ischemic burden (r = 0.36, P < 0.001).

In multivariate discriminant analysis leucocytosis appeared to be the only parameter independently connected with the presence of silent ischemia in the study population (P = 0.0001). The other parameters were diabetes (P = 0.056) and the family history of CAD (P = 0.071), but they did not reach statistical significance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of Multivariate Discriminant Analysis – Selected Parameters

| Parameter | Lambda‐Wilks Coefficient | P |

|---|---|---|

| Leucocytosis | 0.877 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 0.715 | 0.056 |

| Family history | 0.704 | 0.071 |

| Gender | 0.367 | 0.512 |

| Age | 0.456 | 0.312 |

| Smoking | 0.432 | 0.124 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.430 | 0.184 |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.385 | 0.213 |

DISCUSSION

We found that silent ischemic episodes were significantly more frequent in postinfarction asymptomatic patients with WBC count higher than 7.0 × 103/μl. Recent experimental and clinical trials have demonstrated that inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of ACS. 2 , 5 Based on these facts attempts are made to use markers of inflammation as prognostic factors in CAD and ACS.

Numerous investigators have suggested that total WBC count is an important factor in predicting the risk of ischemic heart disease. In 1974 Friedman et al. first reported the association between WBC count and myocardial infarction. 3 Many authors emphasized that the risk of ischemic heart disease is on average two‐fold higher in individuals with WBC > 8.0 to 10.0 × 103/μl compared to those with lower counts of WBC (<4.0 to 6.0 × 103/μl). 3 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 8

Ernst et al. have outlined three mechanisms by which leucocytes may contribute to microvascular injury and promote atherosclerosis and myocardial ischemia. These include pressure‐dependent plugging of microvessels, rheologic properties such as altered deformability and the formation of aggregates when provoked by a variety stimuli, and the release of activated substances including oxygen‐free radicals, proteolytic enzymes, and arachidonic acid metabolites. 9

Studies on the relationship between WBC and ischemic heart disease generally focused on symptomatic patients. However, there is lack of research on this problem in individuals with silent ischemia, whereas it is well known that only 30–40% of patients complain of angina after myocardial infarction. Silent ischemia is reported in approximately 30–40% of asymptomatic patients who survived myocardial infarction. 10 Some authors observed even an increase in this percentage as the time goes by after the infarction. 11

In our study we recorded silent transient ischemic episodes in 49% of the patients. Individuals with WBC count > 7.0 × 103/μl presented with silent ischemia significantly more often than did patients with lower leucocyte count. To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess the relation between the baseline measure of systemic inflammation and the occurrence of silent ischemia.

In addition to the more frequent appearance of silent ischemia in patients with higher WBC count, we have also found the relationship between leucocytosis and the extent of ischemia. The higher the WBC count, the longer and deeper transient ischemic episodes and the greater total ischemic burden. Our findings are consistent with other reports. The majority of studies have demonstrated that progressive increase of WBC count is associated with graded increase in coronary heart disease and acute events risk. In addition, the MRFIT analysis demonstrated that a drop in WBC count was associated with a decrease in such risk. 12 , 13

The positive correlation between the value of the leucocyte count and the severity of ischemia was also confirmed by invasive techniques. Amaro et al. have found three‐vessel CAD significantly more often in patients with leucocyte count higher than 8000/mm3. 14 Similar results were obtained by Kostis et al. 4 At present, there are numerous non‐invasive diagnostic methods to detect ischemia in postinfarction asymptomatic patients with negative predischarge submaximal exercise test. However, Holter monitoring is still considered to be an accessible and the most cost‐effective technique.

Study Limitations

An elevated WBC count may also be a marker for chronic inflammation caused by other pathological conditions. To reduce the influence of other factors on the leucocyte count we did not include in the study patients with chronic inflammatory or neoplasmatic diseases as well as those with acute or chronic infections. However, many chronic inflammatory states are not associated with leucocytosis, and an increased incidence of recognized chronic inflammatory diseases has not been found adequate to explain the ischemia/WBC link in studies addressing this question. 14

Numerous reports indicated that regular cigarette smoking leads to an elevation of the WBC count. 15 , 16 This could mean that WBC count is merely a marker of smoking, which is a well‐established risk factor of atherosclerosis and ischemic heart disease. However, in our study population the percentage of smokers was higher among patients with lower leucocyte count (72% vs 66%). Furthermore, in multivariate analysis smoking was not associated with the presence of silent ischemia. Ensrud et al. obtained similar results in a population of symptomatic patients. 8 The group of patients studied is not representative of all postinfarction asymptomatic patients as we included only those who had myocardial infarction within 6 months before their participation in the study. During long‐term observation of painless patients after infarction, WBC count may help to identify those with higher probability of silent ischemia, but this potential needs to be proven in a large study.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the results obtained we arrived at the following conclusions:

-

1

In postinfarction asymptomatic patients silent ischemia is detected more often in individuals with WBC count higher than 7.0 × 103/μl.

-

2

Postinfarction patients with increased WBC count also have higher total ischemic burden on Holter monitoring.

The results of this study were presented at the 50th Annual Scientific Session of the American College of Cardiology.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cooper HA, Exner DX, Waclawiw MA, et al. White blood cell count and mortality in patients with ischemic and nonischemic left ventricular systolic dysfunction (analysis of the studies of left ventricular dysfunction [SOLVD]). Am J Cardiol 1999;84: 252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koenig W. Inflammation and coronary heart disease: An overview. Cardiol Rev 2001;9: 31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Friedman GD, Klatsky AL, Siegelaub AB. The leukocyte count as a predictor of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1974;290: 1275–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kostis JB, Turkevich D, Sharp J. Association between leukocyte count and the presence and extent of coronary atherosclerosis as determined by coronary arteriography. Am J Cardiol 1984;53: 997–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Libby P. Molecular bases of the acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 1995;91: 2844–2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zalokar JB, Richard JL, Claude JR. Leukocyte count, smoking and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1981;304: 465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kannel WB, Anderson K, Wilson PWF. White blood cell count and cardiovascular disease. Insights from the Framingham Study. JAMA 1992;267: 1253–1256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ensrud K, Grimm R. The white blood cell count and the risk for coronary heart disease. Am Heart J 1992;124: 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ernst E, Hammerschmidt D, Bagge U, et al. Leukocytes and the risk of ischemic disease. JAMA 1987;257: 2318–2324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petretta M, Bonaduce V., Bianchi G, et al. Characterization and prognostic significance of silent myocardial ischemia on predischarge electrocardiographic monitoring in unselected patients with myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1992;69: 579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bolognese L, Rossi L, Sarasso G, et al. Silent versus symptomatic dipiridamole‐induced ischemia after myocardial infarction: Clinical and prognostic significance. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;19: 953–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shoenfeld PJ. Leukopenia and low incidence of myocardial infarction. Lancet 1981;1: 1606–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hansen LK, Grimm RH, Neaton JD (for the MRFIT Research Group) . Factors associated with white blood cell count (WBC) in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT). Council on Epidemiology-CVD Epidemiology Newsletter 1986;107: 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Amaro A, Gonzales‐Juanatey JR, Iglesias C, et al. Leukocyte count as a predictor of the severity of ischemic heart disease as evaluated by coronary angiography. Rev Port Cardiol 1993;899: 913–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chan‐Yeung M, Buncio AD. Leukocyte count, smoking and lung function. Am J Med 1984;76: 31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Petitti DB, Kipp H. The leukocyte count: Associations with intensity of smoking and persistence of effect after quitting. Am J Epidemiol 1986;123: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]