Abstract

Background: Lead aVR is a neglected, however, potentially useful tool in electrocardiography. Our aim was to evaluate its value in clinical practice, by reviewing existing literature regarding its utility for identifying the culprit lesion in acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Methods: Based on a systematic search strategy, 16 studies were assessed with the intent to pool data; diagnostic test rates were calculated as key results.

Results: Five studies investigated if ST‐segment elevation (STE) in aVR is valuable for the diagnosis of left main stem stenosis (LMS) in non–ST‐segment AMI (NSTEMI). The studies were too heterogeneous to pool, but the individual studies all showed that STE in aVR has a high negative predictive value (NPV) for LMS. Six studies evaluated if STE in aVR is valuable for distinguishing proximal from distal lesions in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) in anterior ST‐segment elevation AMI (STEMI). Pooled data showed a sensitivity of 47%, a specificity of 96%, a positive predicative value (PPV) of 91% and a NPV of 69%. Five studies examined if ST‐segment depression (STD) in lead aVR is valuable for discerning lesions in the circumflex artery from those in the right coronary artery in inferior STEMI. Pooled data showed a sensitivity of 37%, a specificity of 86%, a PPV of 42%, and an NPV of 83%.

Conclusion: The absence of aVR STE appears to exclude LMS as the underlying cause in NSTEMI; in the context of anterior STEMI, its presence indicates a culprit lesion in the proximal segment of LAD.

Keywords: ECG, aVR, culprit lesion, myocardial infarction, ischemia

INTRODUCTION

The electrocardiogram (ECG) predicts the location and size of the injured zone during acute myocardial infarction (AMI). 1 Specifically, ST‐segment deviations reflect myocardial ischemia, with important information about first‐line treatment and severity of disease. Over the years many criteria have been developed to strengthen the predictive value of the ECG. However, although the augmented unipolar limb lead aVR was developed more than 60 years ago in order to obtain specific information from the right upper side of the heart, 2 it remains a largely neglected lead for identifying the culprit lesion in clinical practice. 3 , 4 , 5 This is somewhat surprising, as lead aVR may contain important information regarding the ischemic myocardium and the location of the culprit lesion. The right upper side of the heart, that is, the outflow tract of the right ventricle and the basal part of the interventricular septum, is supplied by the main stem of the left coronary artery (LM) and/or branches from the proximal parts of the left anterior descending artery (LAD); hence culprit lesions in these coronary segments cause ST‐segment deviations in lead aVR. Due to the dominance of the basal ventricular mass, this should lead to ST‐segment elevation (STE) in lead aVR, as the ST‐segment vector in the frontal plane points in a superior direction 6 (Fig. 1).

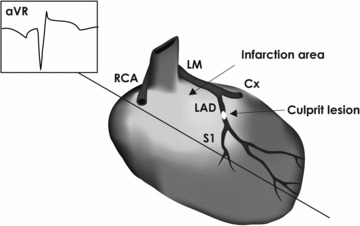

Figure 1.

Culprit lesions in the main stem of the left coronary artery or the proximal part of the left anterior descending artery cause ischemia in the right upper part of the heart, that is the outflow tract of the right ventricle and the basal part of the interventricular septum. Due to the dominance of the basal ventricular mass, this may lead to ST‐segment elevation in lead aVR. Abbreviations: Cx = left circumflex artery; LAD = left anterior descending artery; LM = main stem of left coronary artery; RCA = right coronary artery.

Moreover, lead aVR conveys reciprocal information from the lateral and apical portions of the left ventricle; hence, ischemia in this region may cause mirroring ST‐segment deviations in lead aVR. The myocardium in this region normally receives a bilateral blood supply from the left circumflex artery (Cx) and the right coronary artery (RCA); in this context lead aVR may prove useful to discern inferior AMIs caused by a culprit lesion in Cx from those caused by RCA lesions, 7 since the area supplied by Cx is typically located more leftward in the frontal plane than that supplied by RCA (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Culprit lesions in the left circumflex artery cause ischemia in the lateral and apical parts of the left ventricle. Hence, the ischemic area is more lateralized than that caused by culprit lesions in the right coronary artery. Hence, ischemia in this region may cause mirroring ST‐segment deviations in lead aVR. Abbreviations: Cx = left circumflex artery; LAD = left anterior descending artery; LM = main stem of left coronary artery; RCA = right coronary artery; S1 = first septal branch of the left anterior descending artery.

The aim of the present article was to elucidate the utility of lead aVR in clinical practice, by systematically reviewing the existing literature regarding its implications for identifying the culprit lesion in AMI. Hence, three specific hypotheses were explored: (1) STE in aVR is valuable for the electrocardiographic diagnosis of left main stem stenosis (LMS) in non–ST‐segment elevation AMI (NSTEMI), (2) STE in aVR is valuable for the electrocardiographic distinction between proximal and distal LAD lesions as the cause of anterior ST‐segment elevation AMI (STEMI), and (3) aVR ST‐segment depression (STD) is valuable for the electrocardiographic distinction between Cx and RCA lesions as the cause of inferior STEMI.

METHODS

Literature Search and Data Sources

We searched MEDLINE and Google Scholar. The terms aVR, ischemia, myocardial infarction, and ST segment elevation and ST segment depression were applied in our search strategy. The search was restricted to human studies. We searched reference lists of the included papers, and obtained all relevant papers and review articles. There were no language restrictions.

Relevant papers were included if they held results on the role of lead aVR for identifying the culprit lesion in AMI, and explicitly used relevant inclusion criteria; typical chest pain, clinically significant ST deviations, appropriate alterations in coronary enzyme levels, and definite culprit lesion diagnosis by means of coronary arteriography. Moreover, patients with left bundle branch block, electrocardiographic signs of left ventricular hypertrophy according to the Sokolow–Lyon criteria, as well as a previous history of myocardial infarction or cardiac surgery were all excluded.

We obtained information regarding time of ECG in relation to clinical symptoms and coronary arteriography. Furthermore, we registered how ST‐deviations were assessed, as well as which criteria were used for the angiographic diagnosis of the culprit lesion. Studies with more than 25 patients were included, whereas results from smaller studies were only mentioned.

Data Analysis

Data from the various studies were extracted and pooled in 2 × 2 tables. Fisher's exact test was used to establish significant differences between groups. Diagnostic test rates were calculated as the key results. Two independent observers performed the data extraction and analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Lead aVR in AMI Caused by Left Main Stem Stenosis

We found five relevant papers regarding the implications of lead aVR in AMI caused by LMS. All studies investigated consecutive patients who met the criteria for NSTEMI, two of which specifically assessed patients with a first myocardial infarction, 8 , 9 whereas the remaining three studies included patients with acute coronary syndrome, both with and without AMI. 10 , 11 , 12 In three studies an STE of 0.05 mV was regarded relevant, 10 , 11 , 12 in one study 0.1 mV was considered, 9 whereas one study divided patients according to the degree of aVR STE; 8 hence aVR STEs of 0.05–0.1 mV were considered separately from aVR STEs above 0.1 mV. Lead aVR STE was measured 60 ms after the J‐point in three studies, 9 , 11 , 12 80 ms in one study 8 and 20 ms in another. 10 Coronary arteriography was performed at different times after the ischemic event in the various studies, ranging from days 11 , 12 to months. 8 , 9 Furthermore, the arteriographic definitions of LMS differed between studies; a stenosis of more than 50% 8 was considered significant in one study, whereas 75% was considered significant in two others, 11 , 12 one of which also included the presence of local dissection or thrombosis. 11 Two studies did not report any specific criteria. 9 , 10 In one study, patients with LM and three‐vessel disease were pooled and no differential analyses between the groups were performed. 12 ECG interpreters were blinded in four of the studies, 8 , 9 , 11 , 12 and none of the studies reported blinding of the angiographer.

The prevalence of LMS varied immensely among the studies (Table 1), probably due to the dissimilar study populations, ECG criteria and culprit definitions applied. Thus, we were unable to pool the data. Nonetheless, it appears consistent that aVR STE yields high negative predictive values, whereas the positive predictive values show large disparities (Table 1). Of the five studies, the findings by Barrabés et al. appear to be the most reliable and accurate when evaluating the implications of lead aVR for identifying the LM as the culprit lesion. This study specifically assesses a population of 775 patients with a first myocardial infarction, of which 435 underwent coronary arteriography; angiographic findings were evaluated in relation to aVR STE between 0.05 and 0.1 mV and aVR STE equal to or above 0.1 mV, respectively. LM was identified as the culprit artery in nine patients, of whom two displayed no aVR STE, none had an aVR STE between 0.05 and 0.1 mV, and seven displayed an aVR STE equal to or above 0.1 mV. When an aVR STE of 0.1 mV is considered significant, a NPV of 99% is attained (Table 1) the highest of all the studies. 8

Table 1.

Lead aVR STE for the Diagnosis of LMS in NSTEMI

| Study | Population | aVR STE (mV) | LMS Cases | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMS | Barrabes et al. 8 | 775 | 0.1 | 9 | 77 | 64 | 5 | 99 |

| Hengussamee et al. 11 | 26a | 0.05 | 5 | 80 | 76 | 44 | 94 | |

| Kosuge et al. 12 | 310a | 0.05 | 60b | 78 | 86 | 57 | 95 | |

| Rostoff et al. 42 | 134a | 0.05 | 44 | 68 | 73 | 56 | 83 | |

| Yu et al. 9 | 91 | 0.1 | 9 | 89 | 84 | 38 | 99 |

aStudy populations included patients with acute coronary syndrome, both with and without AMI.

bPatients with LMS and three‐vessel disease were pooled in this study and no differential analyses between groups were performed.

LMS = left main stenosis; NPV = negative predicative value; PPV = positive predicative value.

Lead aVR in Anterior STEMI

We found seven relevant articles, 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 six of which specifically investigated the hypothesis that aVR STE is predictive of proximal LAD lesions, 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 that is before the departure of the first septal branch (S1) from LAD. Engelen was the first to suggest and test different ECG‐criteria for discriminating between proximal and distal lesions. 13 We found that this article had inspired five other studies to test the same hypothesis. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 All studies included patients with signs of anterior STEMI with STE in leads V2–V4. ECGs were evaluated just prior to coronary intervention and if more than one ECG was obtained, the one with the most significant changes was used. Three studies measured STE at the J‐point, in the remaining two studies STE was assessed 40 18 and 80 14 ms after the J‐point, respectively. Two studies considered any STE in lead aVR relevant, 13 , 17 whereas the remaining three studies only considered an STE above 0.05 mV.

The criteria for determining culprit lesion differed between studies, both with regard to time from the insult to coronary arteriography, as well as to the criteria that were used to identify the culprit lesion. Hence, coronary arteriography was performed at various time points, ranging from the acute phase 13 , 14 , 19 and up to 3 weeks after. 18 The culprit lesion was exclusively defined by means of the degree of reduction in diameter of the vessel in two studies, 15 , 17 whereas the remaining studies included signs of a residual thrombus, an ulcerated plaque, and local dissection. 13 , 14 , 18

The pooled data from the six similar studies adds up to 489 patients with anterior STEMI. Of these, 218 (45%) patients had a proximally located culprit lesion, of which 102 had STE in lead aVR, whereas only 10 patients with distally located culprit lesion displayed aVR STE. Fisher's exact test showed significant difference between the groups (2‐tailed P < 0.0001). The combined studies prove high specificity and positive predictive value of STE in lead aVR for proximality of the culprit lesion (Table 2). Diagnostic parameters were not different between studies that regarded any aVR STE and those that only regarded STE above 0.05 mV.

Table 2.

The Utility of Lead aVR for Culprit Diagnostics in STEMI

| Studies | Population | # Relevant Lesion | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prox. LAD lesions (aVR STE) | Pooled data 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 | 489 | 218 | 47 | 96 | 91 | 69 |

| Cx lesions (aVR STD) | Pooled data 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 | 398 | 89 | 35 | 84 | 38 | 82 |

Pooled data for identifying proximal LAD culprit lesions in anterior STEMI (lead aVR STE) and Cx lesions in inferior STEMI (lead aVR STD).

LMS = left main stenosis; NPV = negative predicative value; PPV = positive predicative value; STD = ST‐segment depression; STE = ST‐segment elevation.

Lead aVR in Inferior STEMI

Nair and Glancy were the first to suggest that STD in lead aVR is suggestive of Cx rather than RCA involvement in inferior STEMI. 20 We found three additional original articles 21 , 22 , 23 and one abstract 24 that further addressed this hypothesis. Two studies excluded patients if occlusions were found in both Cx and RCA. 21 , 23 Three studies assessed STD in aVR 60 ms after the J‐point, whereas the remaining study measured STD 20 ms after the J‐point. 22 All studies except for one explicated 0.1 mV to be the relevant STD. 21

The description of time of coronary arteriography from the clinical signs of AMI ranged from “median of 3 days after admission” 25 to “within 7 days.” 20 One study did not report anything on the matter. 21 The culprit lesion was assessed through Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grading in one study, 22 whereas the others defined it by the degree of reduction in diameter of the vessel and included signs of ulcerated plaque and residual thrombus. 20 , 21 , 23 Two studies described blinding of both coronary arteriography and ECG observers. 22 , 23

The pooled data from the four original articles added up to 398 patients with inferior STEMI of which Cx was the culprit artery in 89 patients (22%); of these 31 showed STD in aVR. 50 out of 309 RCA‐related STEMIs showed STE in aVR. Fisher's exact test showed significant difference between the groups (2‐tailed P < 0.0001). In general, STD in lead aVR appears to yield relatively high specificities and negative predictive values, thus indicating that its absence excludes Cx as the culprit (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

It is well established that ST‐deviations in lead aVR predict severity of disease, 8 , 22 , 25 infarction volume, 22 , 25 , 26 , 27 and prognosis 8 in patients with AMI. Furthermore, as reviewed in the present article, lead aVR may also be useful for determining the location of the culprit lesion in patients with AMI caused by LMS, LAD lesions, and RCA/Cx lesions.

Acute coronary syndrome due to LMS exhibits higher mortality rates than any other coronary lesion. LMS is a common cause of ischemic heart disease and is found in 3–5% of patients undergoing coronary arteriography for ischemic chest pain, congestive heart failure, and cardiogenic shock. 8 These patients require specific therapy, including acute coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). 28 , 29 As treatment with platelet inhibitors is routinely used in patients with acute coronary syndrome, but contraindicated prior to CABG, this should not be administered in the case of LMS. 30 Accordingly, early recognition or exclusion of LMS in patients with NSTEMI is crucial in order to identify high‐risk patients and to implement the optimal therapeutic strategy. In this respect, an aVR STE of 0.1 mV may prove useful, as it is more frequent and pronounced in patients with LMS when compared to other coronary lesions. 30 As reviewed in this article, the available evidence proposes that STE in aVR is useful when suspecting LMS in patients with NSTEMI, in the sense that its absence largely excludes LMS as culprit artery; although this notion is based on data from a limited amount of patients, the findings do imply that the clinician should be particularly cautious with regards to platelet inhibitor treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome when aVR STE is present.

None of the studies reviewed in this article addressed aVR STE in the context of other electrocardiographic signs of LMS. Although initial attempts to identify criteria for the electrocardiographic characterization of LMS failed, 31 studies conducted through the 1980s and early 1990s conceptualized the presence of diffuse STD in inferior and anterolateral leads in patients with LMS. 32 , 33 , 34 Thus, the presence of these electrocardiographic signs along with aVR STE may be highly predictive of LMS in patients with acute coronary syndrome, although this needs to be explored further in future studies. Furthermore, it may prove useful to compare STE in leads aVR and V1, as it has been suggested that STE aVR>V1 predicts LMS. 6

The studies that are reviewed in this report uniformly point toward STE in aVR as a useful tool for identifying proximal LAD lesions in the context of other signs of anterior STEMI, that is STE in V2–V4, reflected by high specificities and positive predictive values. Discrimination between proximal and distal LAD lesions is important, as the size of the myocardial infarction and prognosis are worsened by the proximality of the occlusion. 6 , 35 Conversely, the aVR criterion is not very sensitive, and it has therefore been suggested that it should be linked with other criteria. Hence, Eskola et al. recently tested the combined criteria of “any STE in aVR” and an STE of more than 0.05 mV in aVL. This strengthened the sensitivity, but weakened the specificity and positive predictive value equally. 19

Inferior STEMI amounts to 40–50% of all AMIs and is mostly caused by RCA lesions. 35 , 36 , 37 As the clinical outcome and treatment differ between inferior STEMI caused by RCA and Cx lesions, 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 it is of interest to discriminate between them at an early stage. Accordingly, a number of electrocardiographic criteria have been developed (Table 3). The studies reviewed in this report show relatively high specificities and negative predictive values of aVR STD for Cx lesions in inferior STEMI. Although Nair and Glancy initially suggested that this aVR criterion is highly sensitive, 20 it is impossible to establish on basis of the data at hand. When compared to other criteria designed to differentiate between RCA and Cx lesions (Table 3), lead aVR seems to have very little to add. Although aVR STD does not seem to be of much use for identifying the culprit lesion in inferior STEMI, it may nevertheless prove useful, as it has been demonstrated to predict the size of the myocardial infarction. 26 , 27

Table 3.

ECG Criteria for Discerning Cx from RCA Lesions in Inferior STEMI

| Culprit Lesion | ECG Criteria | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cx | aVR STE 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 | 35 | 84 | 38 | 82 |

| V1–V2 STD 20 , 21 , 23 | 75 | 72 | 45 | 91 | |

| I STE 20 , 23 , 43 | 33 | 99 | 94 | 85 | |

| RCA | STD aVL > I 23 , 41 | 65 | 92 | 97 | 41 |

| STE III > II 20 , 21 , 23 , 41 , 43 , 44 | 85 | 72 | 91 | 58 |

Pooled data from studies that examined aVR ST‐segment depression along with other electrocardiographic criteria in the context of inferior STEMI.

Cx = left circumflex artery; LMS = left main stenosis; NPV = negative predicative value; PPV = positive predicative value; RCA = right coronary artery; STD = ST‐segment depression; STE = ST‐segment elevation.

There are several limitations to this study, as there are a number of potential sources of bias and uncertainty. In fact, the LMS studies were so heterogeneous that pooling of the data was not meaningful, although all studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Very few articles explicitly mentioned the use of double blinding. Furthermore, the studies varied much in both angiographic and electrocardiographic definitions.

In conclusion, lead aVR may be useful in clinical practice when assessing patients with acute coronary syndrome as the absence of aVR STE appears to exclude LMS as the underlying cause in NSTEMI, whereas its presence in the context of anterior STEMI indicates a culprit lesion in the LAD, proximal to the first septal branch.

REFERENCES

- 1. Myers GB, Klein HA, Hiratzka T. Correlation of electrocardiographic and pathologic findings in posterolateral infarction. Am Heart J 1949;38:837–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldberger E. A simple, indifferent, electrocardiographic electrode of zero potential and a technique of obtaining augmented, unipolar, extremity leads. Am Heart J 1942;23:483–493. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pahlm US, Pahlm O, Wagner GS. The standard 11‐lead ECG. Neglect of lead aVR in the classical limb lead display. J Electrocardiol 1996;29(Suppl):270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gorgels AP, Engelen DJ, Wellens HJ. Lead aVR, a mostly ignored but very valuable lead in clinical electrocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1355–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Staggs SE, Glancy DL. Clinical uses of electrocardiographic lead aVR. J La State Med Soc 2005;157:308–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yamaji H, Iwasaki K, Kusachi S, et al Prediction of acute left main coronary artery obstruction by 12‐lead electrocardiography. ST segment elevation in lead aVR with less ST segment elevation in lead V(1). J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1348–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nair R, Glancy DL. ECG discrimination between right and left circumflex coronary arterial occlusion in patients with acute inferior myocardial infarction: Value of old criteria and use of lead aVR. Chest 2002;122:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barrabés JA, Figueras J, Moure C, et al Prognostic value of lead aVR in patients with a first non‐ST‐segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2003;108:814–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yu FJ, Fu XH, Wei YL, et al Relationship of acute left main coronary artery occlusion and ST‐segment elevation in lead aVR. Chin Med J (Engl) 2004;117:459–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rostoff P, Piwowarska W. ST segment elevation in lead aVR and coronary artery lesions in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Kardiol Pol 2006;64:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hengrussamee K, Kehasukcharoen W, Tansuphaswadikul S. Significance of lead aVR ST segment elevation in acute coronary syndrome. J Med Assoc Thai 2005;88:1382–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kosuge M, Kimura K, Ishikawa T, et al Predictors of left main or three‐vessel disease in patients who have acute coronary syndromes with non‐ST‐segment elevation. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:1366–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Engelen DJ, Gorgels AP, Cheriex EC, et al Value of the electrocardiogram in localizing the occlusion site in the left anterior descending coronary artery in acute anterior myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhong‐Qun Z, Wei W, Chong‐Quan W, et al Acute anterior wall myocardial infarction entailing ST‐segment elevation in lead V(3)R, V(1) or aVR: Electrocardiographic and angiographic correlations. J Electrocardiol 2008;4:329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koju R, Islam N, Rahman A, et al Electrocardiographic prediction of left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion site in acute anterior myocardial infarction. Nepal Med Coll J 2003;5:64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martinez‐Dolz L, Arnau MA, Almenar L, et al Utilidad del electrocardiograma para predecir el lugar de la oclusión en el infarto agudo de miocardio anterior con enfermedad aislada de la arteria descendente anterior. Rev Esp Cardiol 2002;55:1036–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vasudevan K, Manjunath CN, Srinivas KH, et al Electrocardiographic localization of the occlusion site in left anterior descending coronary artery in acute anterior myocardial infarction. Indian Heart J 2004;56:315–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prieto Solis JA, Gonzalez FC, Hernandez Hernandez MA, et al Predicción electrocardiográfica de la localización de la lesión en la arteria descendente anterior en el infarto agudo de miocardio. Rev Esp Cardiol 2002;55:1028–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eskola MJ, Nikus KC, Holmvang L, et al Value of the 12‐lead electrocardiogram to define the level of obstruction in acute anterior wall myocardial infarction: Correlation to coronary angiography and clinical outcome in the DANAMI‐2 trial. Int J Cardiol 2009;131:378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nair R, Glancy DL. ECG discrimination between right and left circumflex coronary arterial occlusion in patients with acute inferior myocardial infarction: Value of old criteria and use of lead aVR. Chest 2002;122:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baptista SB, Farto e Abreu P, Loureiro JR, et al Identificação electrocardiográfica da artéria relacionada corn o enfarte em doentes corn enfarte agudo do miocárdio inferior. Rev Port Cardiol 2004;23:963–971. 15478322 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kosuge M, Kimura K, Ishikawa T, et al ST‐segment depression in lead aVR: A useful predictor of impaired myocardial reperfusion in patients with inferior acute myocardial infarction. Chest 2005;128:780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun TW, Wang LX, Zhang YZ. The value of ECG lead aVR in the differential diagnosis of acute inferior wall myocardial infarction. Intern Med 2007;46:795–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kurz M, Schmitt A, Irvin C, et al The use of lead aVR to discriminate between right and left circumflex coronary artery occlusion in acute inferior myocardial infarction. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:S127–S128. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kosuge M, Kimura K, Ishikawa T, et al Combined prognostic utility of ST segment in lead aVR and troponin T on admission in non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berger PB, Ryan TJ. Inferior myocardial infarction. High‐risk subgroups. Circulation 1990;81:401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mehta SR, Eikelboom JW, Natarajan MK, et al Impact of right ventricular involvement on mortality and morbidity in patients with inferior myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hind CR, Oldershaw PJ, Miller GA. Left main coronary artery stenosis: Experience of 93 patients. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1982;23:394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Black A, Cortina R, Bossi I, et al Unprotected left main coronary artery stenting: Correlates of midterm survival and impact of patient selection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:832–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gaitonde RS, Sharma N, Ali‐Hasan S, et al Prediction of significant left main coronary artery stenosis by the 12‐lead electrocardiogram in patients with rest angina pectoris and the withholding of clopidogrel therapy. Am J Cardiol 2003;92:846–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cohen MV, Gorlin R. Main left coronary artery disease. Clinical experience from 1964–1974. Circulation 1975;52:275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sclarovsky S, Davidson E, Strasberg B, et al Unstable angina: The significance of ST segment elevation or depression in patients without evidence of increased myocardial oxygen demand. Am Heart J 1986;112:463–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Servi S, Ghio S, Ferrario M, et al Clinical and angiographic findings in angina at rest. Am Heart J 1986;111:6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frierson JH, Dimas AP, Metzdorff MT, et al Critical left main stenosis presenting as diffuse ST segment depression. Am Heart J 1993;125:1773–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Karha J, Murphy SA, Kirtane AJ, et al Evaluation of the association of proximal coronary culprit artery lesion location with clinical outcomes in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2003;92:913–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Elsman P, ‘t Hof AW, Hoorntje JC, et al Effect of coronary occlusion site on angiographic and clinical outcome in acute myocardial infarction patients treated with early coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:1137–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gaudron P, Eilles C, Kugler I, et al Progressive left ventricular dysfunction and remodeling after myocardial infarction. Potential mechanisms and early predictors. Circulation 1993;87:755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saw J, Davies C, Fung A, et al Value of ST elevation in lead III greater than lead II in inferior wall acute myocardial infarction for predicting in‐hospital mortality and diagnosing right ventricular infarction. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:448–450, A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bairey CN, Shah PK, Lew AS, et al Electrocardiographic differentiation of occlusion of the left circumflex versus the right coronary artery as a cause of inferior acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1987;60:456–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Birnbaum Y, Wagner GS, Barbash GI, et al Correlation of angiographic findings and right (V1 to V3) versus left (V4 to V6) precordial ST‐segment depression in inferior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1999;83:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Herz I, Assali AR, Adler Y, et al New electrocardiographic criteria for predicting either the right or left circumflex artery as the culprit coronary artery in inferior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:1343–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rostoff P, Piwowarska W, Konduracka E, et al Value of lead aVR in the detection of significant left main coronary artery stenosis in acute coronary syndrome. Kardiol Pol 2005;62:128–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chia BL, Yip JW, Tan HC, et al Usefulness of ST elevation II/III ratio and ST deviation in lead I for identifying the culprit artery in inferior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:341–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zimetbaum PJ, Krishnan S, Gold A, et al Usefulness of ST‐segment elevation in lead III exceeding that of lead II for identifying the location of the totally occluded coronary artery in inferior wall myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:918–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]