Abstract

The electrocardiogram of a patient with acute pulmonary embolism showed right bundle branch block (RBBB) on alternate beats; following thrombolysis, the pattern evolved to persistent RBBB and eventually to normal conduction. Analysis of serial tracings suggested that the mechanism of RBBB alternans was tachycardia‐dependent bidirectional bundle branch block, caused by prolongation of both anterograde and retrograde refractory periods (RPs) of the right bundle branch (RBB). The sinus impulse found the RBB refractory, and was conducted over the left bundle branch only, depolarizing the left ventricle and then attempting to penetrate retrogradely the RBB; at that time, however, the RBB was still refractory. When a QRS complex had a RBBB configuration, therefore, the RBB was not depolarized; the ensuing sinus impulse found the RBB fully responsive as a consequence of the long period intervening between two successive depolarizations, and resulted in normal intraventricular conduction.

With right ventricular afterload decrease, the recovery of RBB anterograde and retrograde excitability was asynchronous, since the retrograde RP became normal earlier than the anterograde one. In accordance with the relatively short retrograde RP, the RBB was retrogradely invaded by the transseptal impulse coming from the left ventricle; this “shifted to the right” the anterograde RP of the RBB. The RBB, thus, was still refractory to the next sinus impulse, and RBBB again occurred; the RBB, thus, was once more depolarized retrogradely, and this led to perpetuation of RBBB. Finally, intraventricular conduction became normal owing to full normalization of RBB anterograde and retrograde refractoriness.

Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2011;16(3):311–314

Keywords: bundle branch block, electrocardiogram, pulmonary embolism

Bundle branch block (BBB) on alternate beats is usually a rate‐dependent phenomenon occurring only at critical ventricular cycle lengths and disappearing as a result of slight heart rate changes. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 The electrocardiogram (ECG) herewith reported, recorded during an episode of pulmonary embolism, shows regular sinus tachycardia associated with 2:1 right bundle branch block (RBBB). In contrast with the majority of similar cases, the presence or disappearance of BBB alternans is not rate‐dependent, since alternating BBB, persistent BBB, and normal intraventricular conduction all occur at the same sinus rate. Analysis of the ECG suggests that the basic mechanism of BBB alternans is a tachycardia‐dependent (phase‐3) bidirectional block, the variable expressions of intraventricular conduction depending upon changes in duration of right bundle branch (RBB) refractory period (RP).

CASE PRESENTATION

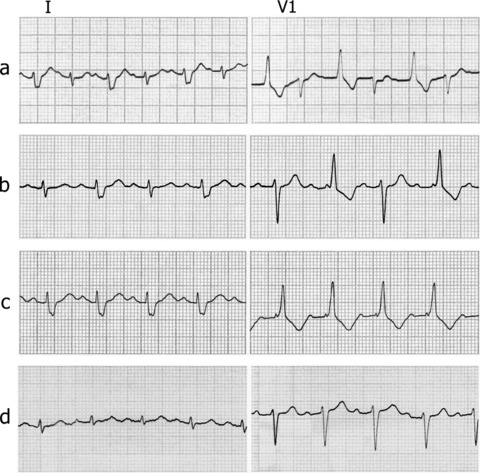

The tracings of Figure 1 (nonsimultaneous strips of leads I and V1) have been recorded from a 60‐year‐old man admitted for syncope, sweating, and severe dyspnoea. A CT scan demonstrating an occlusive thrombus in the left main pulmonary artery supported the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism. The admission tracing (strip a) shows sinus tachycardia at a rate of 135 and a pattern of alternating (2:1) RBBB. Six hours later (strip b), the RBBB alternans is still present despite the sinus rate is decreased to 100. Following thrombolysis, the clinical condition improved, but the ECG (strip c) reveals a worsened intraventricular conduction, as expressed by persistent (1:1) RBBB, despite the heart rate is almost the same as in strip b (103). The ECG recorded on discharge, 10 days later (strip d), shows a sinus rate of 102 associated with normal QRS configuration.

Figure 1.

Serial tracings from the same patient (selected strips of leads I and V1): (a) on admission (heart rate:135); (b) 6 hours later (heart rate:100); (c) shortly after successful thrombolysis (heart rate:103); and (d) on the discharge, 10 days later (heart rate:102).

DISCUSSION

The reported ECG sequence raises the following questions: (1) What is the mechanism of alternating aberration? (2) Why intraventricular conduction shifts from 2:1 (panel b) to 1:1 RBBB (panel c), and eventually to normal (panel d), despite an almost constant heart rate (about 100 bpm)?

BBB on alternate beats in the presence of sinus or supraventricular tachycardia with regular RR intervals can be due to the following mechanisms:

-

1

Tachycardia‐dependent (phase‐3) bidirectional block. An impulse anterogradely blocked in the affected bundle branch (BB) cannot penetrate this in retrograde direction; as a consequence, the pathway benefits from a long time to recover excitability, and the ensuing impulse finds this BB in a nonrefractory state, being normally conducted. 1 , 2 , 3 , 5

-

2

Tachycardia‐dependent (phase‐3) unidirectional (anterograde only) block, associated with supernormal conduction in the impaired BB. 6 , 7 , 8 Each abnormally conducted impulse undergoes retrograde concealed conduction into the blocked BB (the so‐called “linking” phenomenon); 9 , 10 this postpones or “shifts to the right” the BB refractory period and its supernormal “window,” so that the ensuing impulse is allowed to fall within the early phase of improved BB responsiveness, being normally (or less abnormally) conducted. 4 , 6 , 11 Accordingly, BBB alternans results from improved conduction whenever a sinus impulse follows a wide QRS complex (namely, every other beat). 3 , 4 , 5 , 12

Theoretically, both hypotheses 1 and 2 are consistent with the ECG of Figure 1. Supernormal conduction, however, usually occurs with very short ventricular cycles, 5 whereas in this case RBBB alternans is associated with relatively long RR intervals (about 600 ms). In addition, supernormality does not account for perpetuation of 2:1 RBBB with slowing down of the rate from 135 (strip a) to 100 bpm (strip b). If this were the mechanism, a shift to persistent RBBB rather than maintenance of alternans would have been expected following RR interval prolongation from 444 to 600 ms, since at relatively long RR cycles sinus impulses reach the RBB beyond the supernormal “window” and cannot be conducted. 6 The most likely explanation for BBB alternans in this case is phase‐3 bidirectional block, namely tachycardia‐dependent RBBB without retrograde concealed conduction into the anterogradely blocked bundle branch 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 (see below).

The apparent lack of relationship between heart rate and intraventricular conduction, as observed in this report, is an unusual finding. The worsening of conduction from 2:1 to 1:1 BBB, as well as disappearance of the conduction defect, usually result from a progressive slowing down of the heart rate. This changes the relationship between the BB cycle length (the interval from a BB activation, either anterograde or retrograde, and the next attempted anterograde conduction), 1 , 3 the transseptal conduction time and the RPs, both anterograde and retrograde, of the involved pathway. Such a rate‐dependent sequence of events has been referred to as “pseudobradycardia‐dependent alternans,” a variation of tachycardia‐dependent alternans. 1 , 2 In the case herewith reported, the changes in QRS configuration occurring in the presence of a constant sinus rate are likely due to changes in duration of RBB refractory periods (Figure 2). In the clinical setting of pulmonary embolism, such changes may depend on the acute increase, followed by a drug‐induced decrease, of right ventricle afterload. An asynchronous recovery of RBB conduction in the two opposite directions, with a more rapid shortening of the retrograde RP with respect to the anterograde one, is likely responsible for the shift from alternating to persistent RBBB observed before the disappearance of the block.

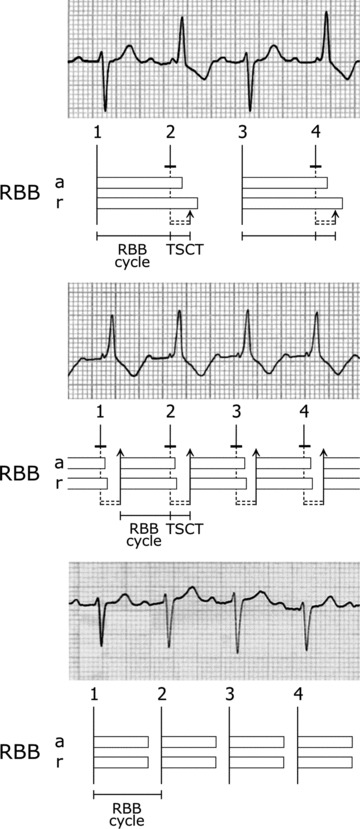

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic explanation of intraventricular conduction (strips of lead V1 from panels b, c, and d of Figure 1). Horizontal bars depict the effective refractory periods (RPs) of the right bundle branch (RBB) (a, anterograde; r, retrograde); the RP of left bundle branch (LBB) is not illustrated. The vertical dashed lines represent conduction over the LBB. The horizontal dashed double lines indicate transseptal conduction. The vertical solid lines represent conduction (either anterograde or retrograde) over the RBB. TSCT: transseptal conduction time. In the top panel, the RBB cycle is the interval from an anterograde successful RBB depolarization to the next attempted anterograde RBB activation. The RBB cycle is shorter than the anterograde RP, and the retrograde RP is longer than the sum of RBB cycle plus TSCT. This generates in the RBB a bidirectional block, causing a 2:1 RBBB. In the middle panel, the RBB cycle is the interval from a retrograde successful depolarization to the next attempted anterograde activation of the RBB. Both anterograde and retrograde RPs of RBB are shorter than in the upper panel, but the retrograde RP shows a higher degree of shortening than the anterograde one. The RBB cycle is shorter than the anterograde RP, and the retrograde RP is shorter than the sum of RBB cycle plus TSCT. The block is unidirectional here, so that retrograde concealed activation of the blocked bundle branch (“linking”) occurs. This postpones the RPs of the RBB in each beat, resulting in repetitive block. In the bottom panel, the RBB cycle corresponds to the time interval between two consecutive anterograde depolarizations of the RBB. The duration of both RBB RPs has returned to normal (anterograde RP <RBB cycle), and the RBBB has disappeared.

The diagrams of Figure 2 explain the mechanism of conduction over the RBB. As a consequence of the acute right ventricular overload, both anterograde and retrograde RPs of the RBB are prolonged, but the latter is markedly longer than the former (top panel). The anterograde RP is longer than a single RBB cycle length (the interval from an anterograde depolarization to the next attempted anterograde activation of RBB) but shorter than the sum of two RBB cycle lengths. In addition, the retrograde RP is longer than the sum of the RBB cycle plus the transseptal conduction time, namely the time spent by the impulse coming from the left bundle branch (LBB) to cross the septum and reach the distal end of the RBB. 1 , 2 As a consequence, impulse 2, that is, blocked anterogradely in the RBB, being conducted to the ventricles over the LBB only, after transseptal conduction finds the RBB still unavailable for retrograde activation, so that the “linking” phenomenon cannot occur: a bidirectional RBBB, thus, manifests. 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 Impulse 3, in turn, falls outside the anterograde RP of the RBB and is normally conducted, starting a new RBB refractoriness; as a result, impulse 4 undergoes once again a bidirectional RBBB.

Following thrombolysis, both RPs of RBB are shortened (Figure 2, middle panel), but the retrograde RP is relatively more shortened than the anterograde one. The retrograde RP is now shorter than the sum of the RBB cycle length plus the transseptal conduction time. As a consequence, every impulse blocked anterogradely in the RBB penetrates this retrogradely following transseptal conduction: in other words, the block is now unidirectional (anterograde only) and concealed retrograde 1:1 RBB conduction occurs 1 , 2 . This “shifts to the right” the RBB refractoriness, thereby generating a sustained anterograde RBBB. 1 , 2 , 9 , 10 , 13

With right ventricular load normalization, the RPs duration of the RBB return to normal (Figure 2, bottom panel), and RBBB disappears.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cohen HC, D’Cruz I, Arbel ER, et al Tachycardia and bradycardia‐dependent bundle branch block alternans. Clinical observations. Circulation 1977;55:242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen HC, D’Cruz IA, Pick A. Effects of stable and changing rates and premature ventricular beats on transient tachycardia‐, pseudobradycardia‐, and bradycardia‐dependent bundle branch block alternans. J Electrocardiol 1979;12:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carbone V, Tedesco MA. Bundle branch block on alternate beats: By what mechanism? J Electrocardiol 2002;35:147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carbone V, Carerj S, Calabrò MP. Bundle branch block on alternate beats during atrial fibrillation. J Electrocardiol 2004;37:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nau GJ, Elizari MV, Rosenbaum MB. The different varieties of 2:1 bundle branch block In Rosenbaum MB, Elizari MV. (eds.): Frontiers in Cardiac Electrophysiology. The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1983, pp. 488–500. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levi RJ, Salerno JA, Nau GJ, et al A reappraisal of supernormal conduction In Rosenbaum MB, Elizari MV. (eds.): Frontiers in Cardiac Electrophysiology. The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1983, pp. 427–456. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klein HO, Di Segni E, Kaplinsky E, et al The supernormal phase of intraventricular conduction: Normalization of intraventricular conduction of premature atrial beats. J Electrocardiol 1982;15:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oreto G, Smeets JL, Rodriguez LM, et al Supernormal conduction in the left bundle branch. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1994;5:345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lehmann MH, Denker S, Mahmud R, et al Linking: A dynamic electrophysiologic phenomenon in macroreentry circuits. Circulation 1985;71:254–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parameswaran R, Monheit R, Goldberg H. Aberrant conduction due to retrograde activation of the right bundle branch. J Electrocardiol 1970;3:173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luzza F, Oreto G, Donato A, et al Supernormal conduction in the left bundle branch unmasked by the linking phenomenon. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1992;15:1248–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Luzza F, Consolo A, Oreto G. Bundle branch block in alternate beats: The role of supernormal and concealed bundle branch conduction. Heart Lung 1995;24:312–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gouaux JL, Ashman R. Auricular fibrillation simulating ventricular paroxysmal tachycardia. Am Heart J 1947;34:366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]