Abstract

Background: There are numerous anecdotal reports of ventricular arrhythmias during spaceflight; however, it is not known whether spaceflight or microgravity systematically increases the risk of cardiac dysrhythmias. Microvolt T wave alternans (MTWA) testing compares favorably with other noninvasive risk stratifiers and invasive electrophysiological testing in patients as a predictor of sudden cardiac death, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation. We hypothesized that simulated microgravity leads to an increase in MTWA.

Methods: Twenty‐four healthy male subjects underwent 9 to 16 days of head‐down tilt bed rest (HDTB). MTWA was measured before and after the bed rest period during bicycle exercise stress. For the purposes of this study, we defined MTWA outcome to be positive if sustained MTWA was present with an onset heart rate ≤125 bpm. During various phases of HDTB, the following were also performed: daily 24‐hour urine collections, serum electrolytes and catecholamines, and cardiovascular system identification (measure of autonomic function).

Results: Before HDTB, 17% of the subjects were MTWA positive [95%CI: (0.6%, 37%)]; after HDTB, 42% of the subjects were MTWA positive [95%CI: (23%, 63%)] (P = 0.03). The subjects who were MTWA positive after HDTB compared with MTWA negative subjects had an increased versus decreased sympathetic responsiveness (P = 0.03) and serum norepinephrine levels (P = 0.05), and a trend toward higher potassium excretion (P = 0.06) after bed rest compared to baseline.

Conclusions: HDTB leads to an increase in MTWA, providing the first evidence that simulated microgravity has a measurable effect on electrical repolarization processes. Possible contributing factors include loss in potassium and changes in sympathetic function.

Keywords: cardiac dysrhythmias, T wave alternans, bed rest, autonomic function, potassium

It is well known that microgravity leads to cardiovascular deconditioning, as evidenced by post‐spaceflight orthostatic intolerance and decreased exercise capacity. However, only anecdotal data exist regarding the possible increased risk of cardiac dysrhythmias during spaceflight. Occasional premature ventricular contractions were seen during the Gemini and Apollo missions. 1 , 2 During Apollo 15, the lunar module pilot also experienced a prolonged run of nodal bigeminy. 3 , 4 Reports indicate that during Skylab, all crew members demonstrated some form of rhythmic disturbances, 1 , 5 and one individual experienced a five‐beat run of ventricular tachycardia. 1 Cardiac dysrhythmias have also been seen during Shuttle flights; 1 , 6 one crew member experienced premature ventricular contractions to rates as high as 16 ectopic beats per minute during reentry. 6 Analysis of nine 24‐hour Holter monitor recordings obtained during long‐term spaceflight on Mir during the joint US–Russian Shuttle‐Mir program revealed one 14‐beat run of ventricular tachycardia. 7 Moreover, it was reported by the Russian medical community to NASA that over the last 10 years on Mir, they had observed 31 abnormal electrocardiograms, 75 dysrhythmias, and 23 conduction disorders [Michael R. Barratt, M.D., and Doug R. Hamilton, M.D., Ph.D., M.Sc. E. Eng P.E., P. Eng., ABIM, FRCPC, personal communications, 2003]. Recently, it was reported that space flight may lead to prolongation of the QTc interval. 8 In another study where cardiac monitoring was performed, no increased risk of dysrhythmias was reported during extra‐vehicular activity (EVA) compared to pre‐ and post‐flight. 9 Thus, while there is some evidence to suggest that spaceflight may be associated with an increased susceptibility to ventricular dysrhythmias, few systematic studies have been conducted and no causal relationship has been established. Furthermore, no prospective studies on the subject of cardiac dysrhythmias have been conducted in the simulated microgravity environment.

The technique of measuring Microvolt T wave alternans (MTWA) has recently been developed and has compared favorably with other noninvasive risk stratifiers and invasive electrophysiological tests as a predictor of sudden cardiac death, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation in clinical studies. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 We hypothesized that simulated microgravity leads to an increase in MTWA. Head‐down tilt bed rest (HDTB) was used to simulate microgravity. One goal of the present study was to assess changes in electrical repolarization processes during HDTB with MTWA. A second goal was to investigate the possible contribution to this phenomenon of physiologic variables (electrolytes, autonomic function) known to be affected by spaceflight 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 and bed rest. 25 , 26

METHODS

Twenty‐four healthy male subjects (age 34.1 ± 2.3 years, weight 78.2 ± 2.0 kg) completed the study. The subjects were nonsmokers and were taking no medication before the study. The exclusion criteria included a history or evidence of hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, renal insufficiency, thyroid disease, hepatitis, anemia, psychiatric disorder, and alcohol or drug abuse.

Protocol

This investigation was part of a larger trial examining the effects of bed rest on the cardiovascular system. 25 , 26 Subjects were admitted to the General Clinical Research Center at Brigham and Women's Hospital, and started on an isocaloric diet containing 200 mEq of sodium, 100 mEq of potassium, 1000 mg of calcium, and 2500 mL of fluid that was maintained through the study period. The subjects were equilibrated on the diet in the research center for 3–5 days before HDTB. Subjects then underwent 9–16 days of 4° HDTB. The sleep–wake cycle remained constant through the entire study, with 8 hours of sleep each day between 22:00 and 6:00 hours in all subjects except 7, who slept from 24:00 to 6:00 hours. Room temperature was maintained between 21 and 22 °C. Subjects were strictly confined to bed for the entire HDTB period. Five of the 24 subjects received the alpha‐1 agonist drug midodrine (Roberts Pharmaceutical, Inc.) on the final day of bed rest about 4 hours before testing as part of a randomized double‐blinded trial of this drug as a countermeasure against orthostatic intolerance. This drug has no known cardiac electrophysiological effects. No other medications, smoking, alcohol, or caffeine was allowed during the study. The study protocol was approved in advance by the Institutional Review Board of the Brigham and Women's Hospital. Each subject provided written informed consent before participating in the study.

Measurements

Measurements for MTWA were made with bicycle exercise at 13:00 hours, 3 hours after a tilt‐stand test that was part of a parallel study. The exercise stress test was conducted at up to 70–80% of the subject's predicted maximum heart rate (maximum predicted heart rate is defined as 220 bpm minus the subject's age in years). Measurements were made with a CH 2000 (Cambridge Heart Inc., Bedford, MA) system. ECG recordings were made with multi‐contact sensors (Micro‐V Alternans Sensors, Cambridge, MA) placed at locations that enabled the recording of both vector and precordial electrocardiograms. MTWA was measured by the Spectral Method. 16 The resulting trend plots were reviewed in a blinded fashion to determine whether sustained alternans occurred during the period of the test and, if they were present, to determine the onset heart rate. Sustained alternans is defined as MTWA, which is consistently present above a subject‐specific onset heart rate. Sustained alternans is considered clinically significant if the onset heart rate is ≤110 bpm. In this study, in order to detect sub‐clinical changes in MTWA, the outcome was considered positive if sustained alternans was present with onset heart rate ≤125 bpm.

The 24‐hour urine samples were collected by voluntary micturition for measurements of daily urine volume and potassium, calcium, magnesium, and creatinine excretion (average of two equilibrated days in the control period = pre‐HDTB; average of the last 2 days of bed rest = end‐HDTB; change over HDTB = end‐HDTB minus pre‐HDTB). Blood samples were collected at 6:00 hours from a peripheral venous catheter after the subject had remained supine overnight on the last day of the pre‐HDTB ambulatory baseline period (pre‐HDTB) and at the completion of HDTB (end‐HDTB) for measurement of potassium, magnesium, calcium, epinephrine, and norepinephrine levels.

During a morning in the pre–bed rest period and at the end of HDTB, data were recorded for cardiovascular system identification (CSI) analysis. The subjects were instrumented for continuous noninvasive monitoring of arterial blood pressure (ABP; Portapres, TNO, or Finapres, Ohmeda), instantaneous lung volume (ILV; Respitrace System, Ambulatory Monitoring Systems), and heart rate (HR; surface electrocardiogram). During data collection, the subjects were instructed to breathe in response to auditory tones spaced at random intervals ranging from 1 to 15 seconds, with a mean of 5 seconds. They controlled their own tidal volume to maintain normal ventilation. This random breathing protocol excites a broad range of frequencies, thereby facilitating system identification. 27 ABP, ILV, and HR data, which were collected with the subject in supine posture, were then saved for CSI analysis offline. 28 , 29

The CSI technique evaluates the interactions between physiologic signals (HR, ABP, and ILV) on a second‐to‐second basis to enable dynamic assessment of important physiologic mechanisms without perturbing normal system operation. From analysis of the physiologic signals, CSI generates a closed‐loop model of cardiovascular regulation specific for the individual subject at the time the signals are collected. CSI may be used to quantify separately the parasympathetic responsiveness and the sympathetic responsiveness. 26

Laboratory Analysis

Blood samples were collected on ice, and the serum or plasma was frozen until assayed. Potassium levels in serum and urine were measured with the AVL 987‐S Electrolyte Analyzer (AVL Scientific Corporation, Roswell, GA). The analyzer uses flame photometry with lithium as an internal standard. Levels of magnesium in serum and urine were measured with colorimetric (bichromatic, 525 nm/692 nm) dye‐complexing methods with Xylidyl blue‐1 as the reagent (ACE Magnesium Reagent, ALFA Asserman West Caldwell, NJ). Calcium levels in plasma and urine were measured with an automated Olympus robot analyzer. A Beckman Creatinine Analyzer 2 (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) was used to measure creatinine concentrations in urine. The KatCombi RIA kit was used to measure plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine (IBL Immuno‐Biological Laboratories, Hamburg, Germany).

Statistical Analysis

Means and standard errors were used to describe the data at baseline and at the end of HDTB. Exact 95% confidence intervals around proportions were calculated by the Blyth–Still–Casella method. The change in MTWA manifestation from baseline to post–bed rest was tested by the exact McNemar's test. We report the unconditional test, which is more powerful than conditioning on the sum of discordant pairs. 30 In addition, we report the one‐sided P‐value to address the specific directional hypothesis of an increase in MTWA occurrence due to bed rest. The StatXact version 5 software was used (Cytel Software Corporation, Cambridge, MA). The analytic tool for group comparisons was the unpaired t‐test (two‐sided), since normality was not rejected. Change due to HDTB was defined as End‐HDTB minus Pre‐HDTB. To compare groups in terms of the change over HDTB, subjects were classified according to TWA status at End‐HDTB. Because the sample sizes were relatively small, the comparisons were repeated with rank methods with consistent results.

RESULTS

MTWA: Typical Example

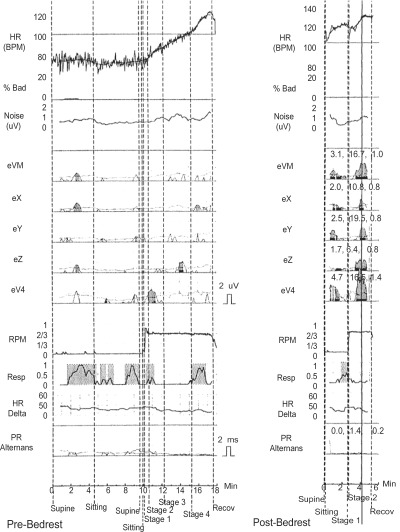

Figure 1 presents a pre‐HDTB MTWA trace on the left versus a post‐HDTB MTWA trace on the right in the same subject. Sustained alternans is present above a patient‐specific heart rate post‐HDTB but is absent pre‐HDTB (see figure legend for details).

Figure 1.

MTWA traces before and immediately after bed rest in the same subject in the vector magnitude lead; vectors leads X, Y, Z; and lead V4. In the left‐hand trace, there is no evidence of sustained alternans. In the right‐hand trace, sustained alternans [MTWA at least 1 minute in duration, with alternans voltage ≥1.9μV, and alternans ratio ≥3 (indicated by gray shading)] is consistently present above the subject's specific onset heart rate in the vector magnitude lead, lead Z, and lead V4 with onset heart rate of 120 bpm.

Changes in MTWA with HDTB

The results of the MTWA tests on the 24 subjects who participated in the study are summarized in Table 1. Before HDTB, 17% of the subjects [95%CI: (0.6%, 37%)] had a positive MTWA; after HDTB, 42%[95%CI: (23%, 63%)] had a positive MTWA. Two of four subjects initially positive became negative with HDTB, and 8 of 20 initially negative became positive (P = 0.03). The large proportion who changed from negative to positive due to HDTB [60%, 95%CI: (36%, 79%)] is particularly noteworthy. Note that none of the onset heart rates for sustained MTWA were less than or equal to the positive heart rate threshold of 110 bpm (below which sustained alternans is usually regarded to be clinically significant).

Table 1.

Results of MTWA Testing before (Pre‐HDTB) and after Head‐Down Tilt Bed Rest (End‐HDTB)

| End‐HDTB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTWA− | MTWA+ | Total | ||

| Pre‐HDTB | MTWA− | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| MTWA+ | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Total | 14 | 10 | 24 | |

P = 0.03.

Incidence of MTWA Pre‐HDTB = 17% (4/24).

Incidence of MTWA End‐HDTB = 42% (10/24).

HDTB = head‐down tilt bed rest; MTWA = microvolt T wave alternans.

Factors Associated with the Development of MTWA

There were no significant differences in the physiological characteristics of MTWA positive and MTWA negative subjects at baseline (Tables 2 and 3). Over the course of HDTB, the MTWA positive subjects (at End‐HDTB) showed an increase versus decrease in serum norepinephrine levels (P = 0.05) (Table 2) and sympathetic responsiveness (P = 0.03) (Table 3) compared to baseline. Furthermore, there was a trend toward a higher potassium excretion compared with baseline in MTWA positive subjects (P = 0.06) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Renal and Cardiovascular Measurements before (pre‐HDTB) and Their Change after Bed Rest (Change over HDTB) Segregated by MTWA Status

| Pre‐HDTB (n = 24) | Change over HDTB (n = 24) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| preMTWA+ (n = 4) | preMTWA− (n = 20) | P Value | endMTWA+ (n = 10) | endMTWA− (n = 14) | P Value | ||

| Serum catecholamines | Epinephrine (pg/mL) | 28.0 ± 11.0 | 38.6 ± 13.2 | 0.72 | −9.9 ± 7.9 | 8.5 ± 12.9 | 0.29 |

| Norepinephrine (pg/mL) | 142 ± 44 | 194 ± 35 | 0.52 | 25 ± 23 | −68 ± 38 | 0.05 | |

| Serum electrolytes | Mg (mEq/L) | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.24 | −0.12 ± 0.08 | −0.04 ± 0.07 | 0.46 |

| K (mEq/L) | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 0.76 | −0.09 ± 0.19 | −0.11 ± 0.07 | 0.93 | |

| Ca (mEq/L) | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 9.4 ± 0.1 | 0.30 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.36 | |

| Urine electrolytes | Mg (mEq/total volume) | 127 ± 13 | 140 ± 5 | 0.32 | 11 ± 7 | 10 ± 6 | 0.90 |

| K (mEq/total volume) | 69.6 ± 8.6 | 79.9 ± 2.9 | 0.17 | 13.3 ± 2.5 | 4.3 ± 3.3 | 0.06 | |

| Ca (mEq/total volume) | 198 ± 21 | 211 ± 19 | 0.75 | 89 ± 22 | 76 ± 15 | 0.63 | |

Data are presented as means ± S.E. Ca = Calcium; endMTWA = MTWA at the end of HDTB; K = Potassium; Mg = Magnesium; MTWA = Microvolt T wave alternans; Pre‐HDTB = pre–head‐down tilt bed rest; preMTWA = MTWA before HDTB; Change = End‐HDTB minus Pre‐HDTB.

Table 3.

Cardiovascular System Identification before (pre‐HDTB) and Their Change after HDTB (Change over HDTB) Segregated by MTWA Status

| Pre‐HDTB (n = 24) | Change over HDTB (n = 24) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| preMTWA+ (n = 4) | preMTWA− (n = 20) | P Value | endMTWA+ (n = 10) | endMTWA− (n = 14) | P Value | ||

| Para‐sympathetic responsiveness | Mean | 0.0238 | 0.0228 | 0.90 | −0.0070 | −0.0070 | 0.87 |

| S.E. | 0.0084 | 0.0030 | 0.0044 | 0.0026 | |||

| Sympathetic responsiveness | Mean | 0.0383 | 0.0255 | 0.48 | 0.0062 | −0.0350 | 0.03 |

| S.E. | 0.0120 | 0.0083 | 0.0121 | 0.0111 | |||

Measurements were taken in the supine position. endMTWA = MTWA at the end of HDTB; MTWA = Microvolt T‐wave alternans; pre‐HDTB = pre‐head‐down tilt bed rest; preMTWA = MTWA before HDTB; S.E. = standard error; Change = End‐HDTB minus Pre‐HDTB; sympathetic and parasympathetic responsiveness are unitless.

DISCUSSION

Using MTWA testing to assess cardiac repolarization processes, we demonstrated an increase from 17% to 42% in the incidence of MTWA with bed rest in healthy male subjects. In patients with structural heart disease, MTWA has been associated with increased risk of sudden death. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 19 , 31 Although none of the onset heart rates for MTWA in this study were below the onset heart rate considered clinically significant for risk of sudden death, this represents the first evidence that simulated microgravity has an effect on cardiac repolarization processes.

Microvolt T Wave Alternans

T wave alternans involving an ABABAB pattern of variation in T wave morphology in sequential beats is a phenomenon that has been recognized for nearly 100 years. The recently developed technique of microvolt T wave alternans testing measures fluctuations in the morphology of the T wave that cannot be seen upon visual inspection of the electrocardiogram. 16 In a range of animal 16 , 32 and human studies, 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 19 , 31 MTWA has been shown to identify patients at increased risk of sudden cardiac death, cardiac arrest, and sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias. The mechanism linking microvolt T wave alternans to the development of reentrant ventricular arrhythmias has been explored in a number of theoretical and experimental papers. 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 The prevailing view is that disease processes may lead to localized alteration in the steepness of the cellular restitution curve, which characterizes the relationship between action potential duration and the duration of the preceding diastolic interval or the heart rate.

Cardiac Conduction Properties during Spaceflight

In this study, bed rest led to an increase in MTWA in healthy male subjects. Besides reports of occurrences of ventricular dysrhythmias missions, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 only a few studies have been conducted to assess prospectively objective changes in myocardial electrical properties. D'Aunno et al. have reported an increased QTc interval after spaceflight. 8 However, in a study by Rossum et al. in which 7 astronauts were studied with Holter or a standard operational bioinstrumentation system during EVA, no increases in cardiac dysrhythmias were seen during EVA (a period thought to be at increased risk of dysrhythmias) compared with pre‐ and postflight. 9

Factors Associated with Development of MTWA in This Study

Simulated and real microgravity is known to induce several physiologic changes; some of these could be related to an increased risk for cardiac dysrhythmias. In a previous study, we documented an increased urinary loss of potassium and an increase in plasma renin activity with bed rest. 25 In the present study, we observed that patients who were positive for MTWA after bed rest demonstrated an increase versus decrease in sympathetic responsiveness and serum norepinephrine levels compared with baseline values, and a trend toward a greater loss of potassium compared with baseline. The contribution of the sympathetic nervous system to the pathogenesis of cardiac dysrhythmias has been long recognized. 37 , 38 , 39 , 40

Four individuals were classified as positive pre‐bed rest. Exposure to bed rest resulted in two of these four individuals being no longer classified as positive. In contrast, 8 of 20 subjects who were not MTWA positive prior to bed rest became positive after bed rest. These observations might suggest that bed rest alters cardiac repolarization processes in a manner that may either increase or decrease susceptibility to the development of sustained alternans. However, the number of individuals converting from positive to negative is too small to come to any firm conclusion in this regard.

Although no conclusions can be drawn from the present study in relation to the duration of simulated microgravity exposure and the development of MTWA, we suspect that prolonged exposure to simulated microgravity may lead to increased levels of MTWA by compounding of cardiac, renal, and autonomic alterations that occur in that environment.

Implications for Terrestrial Medicine

The present findings have implications for terrestrial medicine. Cardiac dysrhythmias are a common phenomenon in cardiac and bedridden patients. Several of these patients are also receiving diuretics. Bed rest and potassium loss might contribute to the development of cardiac dysrhythmias in these patients. This issue needs to be explored further.

CONCLUSIONS

This prospective study indicates that short duration bed rest alters cardiac repolarization processes in a manner that might increase susceptibility to ventricular dysrhythmias. This finding needs to be noted in the context of planned manned space missions that may involve many months or even years of exposure to microgravity. Further studies are needed, particularly to examine the effects of exposure to long duration microgravity on cardiac electrical stability. The present study also suggests that potassium loss and alterations in sympathetic activity may contribute to the development of MTWA. Dietary potassium supplementation and adrenergic blockers are thus potential countermeasures. Furthermore, these findings may have implications with regard to the risk of ventricular dysrhythmias in patients confined to bed for prolonged periods.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) supported this work through the NASA Cooperative Agreement NCC 9‐58 with the National Space Biomedical Research Institute. The studies were conducted on the General Clinical Research Center of the Brigham and Women's Hospital, supported by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources (5M01RR02635). Dr. Grenon wishes to thank the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada for a Post‐Doctoral Junior Fellowship Award. Dr. Ramsdell is presently affiliated with the Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Williams Beaumont Hospital, 3601, West Thirteen Mile Road, Royal Oak, MI 48073.

Sources of Support: National Space and Biomedical Research Institute (NASA), One Baylor Plaza, NA‐425, Houston, TX 77030, Telephone: 713‐798‐7412, Fax: 713‐798‐7413.

Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Suite 1402, 222 Queen Street, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5V9, Canada. Telephone: 613‐569‐4361 ext. 327, Fax: 613‐569‐3278.

REFERENCES

- 1. Charles JB, Bungo MW, Fortner W. Cardiopulmonary function In: Nicogossian A, Huntoon C, Pool S. (eds.): Space Physiology and Medicine, 3rd Edition Philadelphia , Lea & Febiger, 1994, pp. 286–304. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hawkins WR, Zieglschmid JF. Clinical aspects of crew health In: Johnston R, Dietlein LD, Berry CA. (eds.): Biomedical Results of Apollo (NASA SP‐368), Section II, Chapter 1. Washington , DC , Government printing office , 1975. (http://lsda.jsc.nasa.gov/books/apollo/cover.htm, accessed January 6, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dietlein LF. Summary and conclusions In: Johnston RL, Dietlein LF, Berry CA. (eds.): Biomedical Results of Apollo (NASA SP‐368), Section VII, Chapter 1. Washington , DC , Government Printing Office , 1975. (http://lsda.jsc.nasa.gov/books/apollo/cover.htm, accessed January 6, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Douglas WR. Current status of space medicine and exobiology. Aviat Space Environ Med 1978;49: 902–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith R, Stanton K, Stoop D, et al Vectorcardiographic changes during extended space flight (M093): Observations at rest and during exercise In: Johnson RS, Dietlein LF. (eds.): Biomedical Results of Skylab (NASA SP‐377), Section V, Chapter 33. Washington , DC , 1977. (http://lsda.jsc.nasa.gov/book/skylab/skylabcover.htm, accessed January 6, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bungo MW, Johnson PC, Jr . Cardiovascular examinations and observations of deconditioning during the space shuttle orbital flight test program. Aviat Space Environ Med 1983;54: 1001–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fritsch‐Yelle JM, Leuenberger UA, D'Aunno DS, et al An episode of ventricular tachycardia during long‐duration spaceflight. Am J Cardiol 1998;81: 1391–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'Aunno D, Dougherty AH, Deblock HF, et al Effect of short‐ and long‐duration spaceflight on QTc intervals in healthy astronauts. Am J Cardiol 2003;91: 494–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rossum AC, Wood ML, Bishop SL, et al Evaluation of cardiac rhythm disturbances during extravehicular activity. Am J Cardiol 1997;79: 1153–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bloomfield DM, Hohnloser SH, Cohen RJ. Interpretation and classification of microvolt T wave alternans tests. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2002;13: 502–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klingenheben T, Zabel M, D'Agostino RB, et al Predictive value of T‐wave alternans for arrhythmic events in patients with congestive heart failure. Lancet 2000;356: 651–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenbaum DS, Jackson LE, Smith JM, et al Electrical alternans and vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias. N Engl J Med 1994;330: 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gold MR, Bloomfield DM, Anderson JM, et al A comparison of T‐wave alternans, signal averaged electrocardiography and programmed ventricular stimulation for arrhythmia risk stratification. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36: 2247–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ikeda T, Saito H, Tanno K, et al T‐wave alternans as a predictor for sudden cardiac death after myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2002;89: 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ikeda T, Sakata T, Takami M, et al Combined assessment of T‐wave alternans and late potentials used to predict arrhythmic events after myocardial infarction. A prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35: 722–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith JM, Clancy EA, Valeri CR, et al Electrical alternans and cardiac electrical instability. Circulation 1988;77: 110–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hohnloser SH, Klingenheben T, Bloomfield D, et al Usefulness of microvolt T‐wave alternans for prediction of ventricular tachyarrhythmic events in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: Results from a prospective observational study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41: 2220–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hohnloser SH, Ikeda T, Bloomfield DM, et al T‐wave alternans negative coronary patients with low ejection and benefit from defibrillator implantation. Lancet 2003;362: 125–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kitamura H, Ohnishi Y, Okajima K, et al Onset heart rate of microvolt‐level T‐wave alternans provides clinical and prognostic value in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39: 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leach CS, Alfrey CP, Suki WN, et al Regulation of body fluid compartments during short‐term spaceflight. J Appl Physiol 1996;81: 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Drummer C, Hesse C, Baisch F, et al Water and sodium balances and their relation to body mass changes in microgravity. Eur J Clin Invest 2000;30: 1066–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fritsch‐Yelle JM, Charles JB, Jones MM, et al Spaceflight alters autonomic regulation of arterial pressure in humans. J Appl Physiol 1994;77: 1776–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fritsch‐Yelle JM, Whitson PA, Bondar RL, et al Subnormal norepinephrine release relates to presyncope in astronauts after spaceflight. J Appl Physiol 1996;81: 2134–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fritsch‐Yelle JM, Charles JB, Jones MM, et al Microgravity decreases heart rate and arterial pressure in humans. J Appl Physiol 1996;80: 910–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grenon SM, Sheynberg N, Hurwitz S, et al Renal, endocrine, and cardiovascular responses to bed rest in male subjects on a constant diet. J Investig Med 2004;52: 117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xiao X, Mukkamala R, Sheynberg N, et al Effects of simulated microgravity on closed‐loop cardiovascular regulation and orthostatic intolerance: Analysis by means of system identification. J Appl Physiol 2004;96: 489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berger RD, Saul JP, Cohen RJ. Assessment of autonomic response by broad‐band respiration. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1989;36: 1061–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mukkamala R, Mathias JM, Mullen TJ, et al System identification of closed‐loop cardiovascular control mechanisms: Diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Am J Physiol 1999;276: R905–R912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mullen TJ, Appel ML, Mukkamala R, et al System identification of closed‐loop cardiovascular control: Effects of posture and autonomic blockade. Am J Physiol 1997;272: H448–H461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Suissa S, Shuster JJ. The 2 × 2 matched‐pairs trial: Exact unconditional design and analysis. Biometrics 1991;47: 361–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hohnloser SH, Klingenheben T, Li YG, et al T wave alternans as a predictor of recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias in ICD recipients: Prospective comparison with conventional risk markers. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1998;9: 1258–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verrier RL, Nearing BD. Electrophysiologic basis for T wave alternans as an index of vulnerability to ventricular fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1994;5: 445–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pastore JM, Girouard SD, Laurita KR, et al Mechanism linking T‐wave alternans to the genesis of cardiac fibrillation. Circulation 1999;99: 1385–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pastore JM, Rosenbaum DS. Role of structural barriers in the mechanism of alternans‐induced reentry. Circ Res 2000;87: 1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chinushi M, Restivo M, Caref EB, et al Electrophysiological basis of arrhythmogenicity of QT/T alternans in the long‐QT syndrome: Tridimensional analysis of the kinetics of cardiac repolarization. Circ Res 1998;83: 614–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Armoundas AA, Tomaselli GF, Esperer HD. Pathophysiological basis and clinical application of T‐wave alternans. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40: 207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. The Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS‐II): A randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353: 9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lichstein E, Morganroth J, Harrist R, et al Effect of propranolol on ventricular arrhythmia. The beta‐blocker heart attack trial experience. Circulation 1983;67: I5–I10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klingenheben T, Gronefeld G, Li YG, et al Effect of metoprolol and d,l‐sotalol on microvolt‐level T‐wave alternans. Results of a prospective, double‐blind, randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38: 2013–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Exner DV, Reiffel JA, Epstein AE, et al Beta‐blocker use and survival in patients with ventricular fibrillation or symptomatic ventricular tachycardia: The Antiarrhythmics versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34: 325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]