Abstract

Background: Essential hyperhidrosis has been associated with an increased activity of the sympathetic system. In this study, we investigated cardiac autonomic function in patients with essential hyperhidrosis and healthy controls by time and frequency domain analysis of heart rate variability (HRV).

Method: In this study, 12 subjects with essential hyperhidrosis and 20 healthy subjects were included. Time and frequency domain parameters of HRV were obtained from all of the participants after a 15‐minute resting period in supine position, during controlled respiration (CR) and handgrip exercise (HGE) in sitting position over 5‐minute periods in each stage.

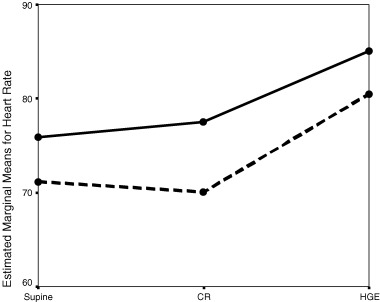

Results: Baseline values of HRV parameters including RR interval, SDNN and root mean square of successive R‐R interval differences, low frequency (LF), high frequency (HF), normalized unit of high frequency (HFnu), normalized unit of low frequency (LFnu), and LF/HF ratio were identical in two groups. During CR, no difference was detected between the two groups with respect to HRV parameters. However, the expected increase in mean heart rate (mean R‐R interval) did not occur in hyperhidrotic group, whereas it did occur in the control group (Friedman's P = 0.000). Handgrip exercise induced significant decrease in mean R‐R interval in both groups and no difference was detected between the two groups with respect to the other HRV parameters. When repeated measurements were compared with two‐way ANOVA, there was statistically significant difference only regarding mean heart rate in two groups (F = 6.5; P = 0.01).

Conclusion: Our overall findings suggest that essential hyperhidrosis is a complex autonomic dysfunction rather than sympathetic overactivity, and parasympathetic system seems to be involved in pathogenesis of this disorder.

Keywords: essential hyperhidrosis, cardiac autonomic regulation, heart rate variability

Essential hyperhidrosis is a disorder of excessive sweating beyond the amount needed to cool down an elevated body temperature probably due to excessive activity of the second and third thoracic ganglia. Typical locations of excessive sweating are the axillary, palmoplantar, and axillopalmoplantar regions. 1 Therapeutic approaches include sympathectomy, local application of aluminum chloride, iontophoresis, and local injections of botulinum A toxin. 2 , 3 , 4 Interruption of the sympathetic chain at the T2–T4 level by thoracoscopic intervention is considered an effective and safe treatment for essential hyperhidrosis refractory to conventional therapy. 5 , 6 , 7 The principle of sympathectomy is to interrupt the nerve tracts and ganglia that transmit the signals to the sweat glands. The T2 and T4 ganglia are also in the direct pathway of sympathetic innervation of the heart. 8 Therefore, it is speculated that essential hyperhidrosis is not only a local disturbance but also results from general dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, and also involving cardiac autonomic control. However, to date, only a few studies have focused on autonomic control of the cardiovascular system in hyperhidrotic patients.

In clinical practice, heart rate variability (HRV) is a valuable and reproducible noninvasive tool for assessment of autonomic cardiovascular function. Indexes of the HRV reflect cardiac autonomic tone. 9 , 10 Decreased HRV has been reported to be an early sign of autonomic neuropathy. 11 Frequency domain and time domain parameters have been recommended for HRV analysis with 5‐minute (short‐term) recordings. 10 Therefore, the objective of this study is to investigate the cardiac autonomic function of patients suffering from essential hyperhidrosis by time and frequency domain analysis of HRV and to compare with those with healthy subjects.

METHOD

In this study, 12 subjects with essential hyperhidrosis and 20 healthy subjects were included (Group 1). As a control group, sex–age matched, 20 healthy subjects were investigated (Group 2). Diagnosis of essential hyperhidrosis was confirmed by ninhydrin sweat test on the hyperhidrotic regions. 12 The subjects with known coronary artery disease, respiratory, neurological, or systemic, or any other disorder that might influence the autonomic function, history of smoking, and diabetes mellitus were excluded from the study. No subject was taking any medication at the time of study.

Study Design

All subjects, having a light breakfast after an overnight fasting period, were taken to a quite, dimly lit, and 22–24°C‐temperature room. All participants were asked to refrain from alcohol and caffeine‐containing beverages and strenuous exercise for 24‐hour prior to study. The studies were performed between 9 pm and 12:00 pm to avoid circadian variation of HRV parameters. All participants rested in supine position (S) at least 15 minutes on a comfortable bed. Electrocardiographic (ECG) records at a speed of 25 mm/s were taken at S and during controlled respiration (CR) and HGE in sitting position over 5‐minute periods in each stage. Controlled respiration and HGE were performed in order to test the alteration during parasympathetic and sympathetic stimulation, respectively. Controlled respiration was performed with a metronome at a rate of 15/dk (0.25 Hz). Participants performed an isometric HGE at 25% of their predetermined maximum volunteer capacity in a manner of 45 second contraction and 15 second resting per minute using Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer (Sammons Preston, Canada).

Heart Rate Variability Analysis

Electrocardiographic data were fed to a personal computer and digitized via an analog‐to‐digital conversion board (PC‐ECG 1200, Norav Medical Ltd., Israel). All records were visually examined and manually over‐read to verify beat classification. Abnormal beats and areas of artifact were automatically and manually identified and excluded. Heart rate variability analysis was performed using Heart Rate Variability Software (version 4.2.0, Norav Medical Ltd., Israel). Both time and frequency domain analyses were performed. For the time domain, mean RR interval (mean RR), the standard deviation of RR interval (SDNN), and the root mean square of successive RR interval differences (RMSSD) were measured. For the frequency domain, analysis power spectral analysis based on the Fast Fourier transformation algorithm was used. Three components of power spectrum were computed following bandwidths: high frequency (HF) (0.15–0.4 Hz) and low frequency (LF) (0.04–0.15 Hz). The LF/HF ratio, LFnu, and HFnu were also calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Mann‐Whitney U test was used for comparison of baseline values. Repeated measurements were analyzed with Friedman's test to assess differences between each phase. Two‐way ANOVA model was used to compare effects of study phases on HRV parameters. The test was performed with either hyperhidrotic group or control group as the between‐subject factor and the phases of the study as the within‐subject factor. Wilcoxon signed‐rank test was implemented for pairwise comparisons and post hock tests. The 0.05 level of significance was used for ANOVA models and pairwise comparisons, and 0.01 level was considered for post hoc tests.

RESULTS

There was no significant difference between the two groups in demographics of age, sex, and heart rate. Tables 1 and 2 show the HRV parameters of hyperhidrotic patients and control subjects, respectively. Baseline values of HRV parameters including R‐R interval, SDNN and RMSSD, LF, HF, HFnu, LFnu, and LF/HF ratio were identical in two groups. During CR, no difference was detected between the two groups with respect to HRV parameters. However, during CR the expected decrease in heart rate did not occur in hyperhidrotic group, whereas it did occur in control group as would be expected. Handgrip exercise induced significant increase in heart rate in both groups and no difference was detected between two groups with respect to HRV parameters. When repeated measurements were compared with Friedman's test in the hyperhidrotic group, all of the parameters but mean RR interval were altered while in control group all of the parameters were altered. In addition, when repeated measurements of HRV parameters in each stage were compared with two‐way ANOVA; there was statistically significant difference only regarding mean heart rate (mean RR) interval in two groups (F = 6.5; P = 0.01) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

The Change in the Time and Frequency Domain Parameters of Heart Rate Variability in Three Phases of the Study in Hyperhidrotic Subjects

| Variable | S | P* | CR | P** | HGE | P*** | Friedman's P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 803 ± 97 | 0.09 | 789 ± 111 | 0.004 | 713 ± 74 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| SDNN | 41 ± 9 | 0.9 | 42 ± 12 | 0.025 | 50 ± 13 | 0.045 | ns |

| RMSSD | 31 ± 10 | 0.72 | 32 ± 12 | 0.15 | 27 ± 8 | 0.077 | ns |

| LF | 194 ± 56 | 0.41 | 172 ± 60 | 0.03 | 233 ± 60 | 0.15 | ns |

| HF | 160 ± 83 | 0.3 | 188 ± 88 | 0.028 | 109 ± 66 | 0.002 | ns |

| LF/HF | 1.45 ± 0.6 | 0.43 | 1.25 ± 0.9 | 0.019 | 3.1 ± 2.4 | 0.005 | ns |

| Lfnu | 57 ± 12 | 0.3 | 49 ± 18 | 0.004 | 69 ± 13 | 0.013 | 0.018 |

| Hfnu | 43 ± 12 | 0.3 | 51 ± 18 | 0.004 | 31 ± 13 | 0.013 | 0.018 |

Wilcoxon signed‐rank test; P* S versus CR; P** CR versus HGE; P*** S versus HGE.

Abbreviations: S = supine; CR = controlled respiration; HGE = handgrip exercise.

Table 2.

The Change in the Time and Frequency Domain Parameters of Heart Rate Variability in Three Phases of the Study in Control Subjects

| Variable | S | P* | CR | P** | HGE | P*** | Friedman's P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 881 ± 107 | 0.01 | 907 ± 128 | 0.000 | 774 ± 83 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| SDNN | 53 ± 29 | 0.6 | 54 ± 26 | 0.09 | 61 ± 18 | 0.062 | 0.018 |

| RMSSD | 44 ± 21 | 0.8 | 45 ± 19 | 0.001 | 33 ± 12 | 0.007 | 0.02 |

| LF | 160 ± 49 | 0.06 | 134 ± 61 | 0.002 | 210 ± 69 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| HF | 151 ± 68 | 0.02 | 202 ± 108 | 0.000 | 75 ± 46 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| LF/HF | 1.36 ± 0.8 | 0.14 | 1.11 ± 0.9 | 0.000 | 3.5 ± 1.8 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Lfnu | 53 ± 16 | 0.03 | 43 ± 23 | 0.000 | 75 ± 10 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Hfnu | 47 ± 16 | 0.01 | 57 ± 23 | 0.03 | 25 ± 10 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Wilcoxon signed‐rank test; P* S versus CR; P** CR versus HE; P*** S versus HGE.

Abbreviations: S = supine; CR = controlled respiration; HGE = handgrip exercise.

Figure 1.

The change in mean heart rate (mean RR interval) in three phases of the study in hyperhidrotic subjects (continuous line) and control subjects (dotted line). Abbreviations: CR = controlled respiration; HGE = handgrip exercise.

DISCUSSION

Excessive sweating or essential hyperhidrosis is a well‐recognized dermatologic and neurological disorder. The etiology of this disturbance is unknown but it has been associated with an increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system. 13 , 14 , 15 It is considered to result from excessive activity of the second and third thoracic ganglia. Interruption of the sympathetic chain at the T2–T4 level by thoracoscopic intervention is an effective and safe treatment and provides clinical and symptomatic improvement particularly in refractory cases to conventional therapies. 5 , 6 , 7 Accordingly, the T2 and T4 ganglia are also in the direct pathway of sympathetic innervation of the heart. 8 It is reasonable to think that sympathetic fibers passing through T2 and T4 ganglia may affect autonomic control of the heart. We, therefore, using short‐term HRV analysis, have investigated the changes in autonomic modulation of heart rate in a group of patients with essential hyperhidrosis and healthy subjects at rest, during CR and HGE, which may alter sympathovagal balance. We found no difference with respect to signs of sympathetic overactivity in the patients with hyperhidrosis either in resting condition or during CR and HGE compared with healthy controls. However, during CR, decrease in heart rate did not occur in hyperhidrotic subjects, whereas it did occur in control subjects as would be expected.

Heart rate variability has been reported to be a useful tool with a reproducibility sufficient to evaluate cardiac autonomic modulation. Decreased HRV has been shown to be an early sign of autonomic neuropathy. 11 Indexes of the HRV reflect cardiac autonomic tone. 9 , 10 Power spectral analysis of the beat‐to‐beat variation of the heart rate is a noninvasive method that is used to study the sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation of cardiovascular system. The HRV signal is the sum of a number of oscillation components. 10 The power of LF represents a complex combination of sympathetic and parasympathetic effects on cardiac autonomic function, whereas high frequencies are mediated primarily by vagal innervation of the heart. 10 , 16 LF/HF ratio is commonly regarded as an index of sympathovagal balance. 10 In time domain analysis of HRV, SDNN represents sympathetic activity, whereas RMSSD represents parasympathetic component of autonomic function. 10

So far, there are only a limited number of studies that have investigated cardiac autonomic function in patients with essential hyperhidrosis in order to demonstrate putative role of sympathetic hyperactivity. 13 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 However, controversial results have been reported concerning whether cardiac autonomic functions are altered in this disorder. 13 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 Shih et al. 17 reported that patients with denervation of T2–T3 ganglia because of palmar hyperhidrosis showed altered sweating response on the whole body during physical exercise compared to normal subjects and patients suffering from palmar hyperhidrosis. In accordance with our findings, hyperhidrotic subjects with intact ganglia also showed less bradycardia in response to the Valsalva maneuver and a higher degree of cutaneous vasoconstriction in response to finger or cold immersion. The authors suggested an over‐functioning of sympathetic fibers running through T2–T3 as the cause of palmar hyperhidrosis, which leads to generalized autonomic dysfunction. 17 Other authors suggested that palmoplanter hyperhidrosis is only secondary to the hyperresponse to the mental and emotional stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, and instead originates in cerebral cortex. 13 Noppen et al. 14 reported a higher peak heart rate in subjects with focal hyperhidrosis at physical exercise, which normalizes after sympathicolysis. The authors concluded that sympathetic overactivity relevant to cardiac function in hyperhidrosis is only evident during sympathetic stimulation. 14 However, the authors have only assessed cardiopulmonary exercise capacity but not HRV, 1 week before and 1 month after sympathicolysis in their study. On the other hand, Kingma et al. 15 investigated effects of thoracic sympathectomy of T2–T4 on hemodynamics and baroreflex control of the heart and found that thoracic sympathectomy decreased mean heart rate and mean blood pressure, but autonomic function test outcomes did not alter, although measurable changes in cardiovascular control appeared, particularly in total peripheral resistance. In addition, Birner et al. 18 compared cardiac autonomic functions in patients with primary focal hyperhidrosis and healthy controls by short‐term frequency domain power spectral analysis of HRV and found no evidence of cardiac sympathetic dysfunction, in contrast, observed parasympathetic dysfunction at autonomic stimulation in hyperhidrotic subjects compared to normal subjects. The authors concluded that primary focal hyperhidrosis was based on much more complex dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system than generalized sympathetic overactivity. 18 These results were definitely in accordance with our findings. However, in that study frequency but not time domain analysis was performed. More recently, Senard et al. 19 assessed blood pressure and HRV at rest and during head‐up tilt test in patients with essential hyperhidrosis and compared those of controls and observed at rest, a higher relative energy of LF band of systolic blood pressure in hyperhidrotic subjects in comparison with controls contrasting with the lack of difference in blood pressure, heart rate and in other spectral parameters. The authors concluded that in essential hyperhidrosis, sympathetic nervous system was not overactive even if resting overactivity could not be excluded. However, in that study the authors used frequency but not time domain analysis of the HRV and they assessed the changes only during head‐up tilt test and did not investigate parasympathetic maneuver's effect on HRV. Our results were partly in accordance with the finding of this study because we found no difference between the two groups regarding HRV parameters at rest. In contrast, we found that parasympathetic tone could not be augmented in hyperhidrotic subjects with a parasympathetic maneuver such as CR. Therefore, our findings suggest that although there is no difference between hyperhidrotic subjects and control subjects with respect to sympathetic/parasympathetic modulation of the heart, parasympathetic tone could not be augmented in hyperhidrotic subjects.

We included only a limited number of subjects in the study and therefore our results could not be extrapolated to all hyperhidrotic subjects. In addition, we did not assess plasma noradrenalin level, which may indicate sympathetic overactivity. However, Senard et al. 19 already showed that there was no difference with respect to plasma noradrenalin levels between two groups either in resting or during head‐up tilt test.

In conclusion, we observed that hyperhidrotic subjects had no any finding of sympathetic nervous system overactivity at rest in comparison with healthy subjects and their responses to maneuvers that may alter autonomic control of the heart were not different than those of healthy control subjects. Instead we observed parasympathetic dysfunction at autonomic stimulation in hyperhidrotic subjects compared to normal controls. Our study indicates that essential hyperhidrosis may be a much more complex dysfunction of autonomic nervous system, also involving parasympathetic system rather than only a generalized sympathetic overactivity. However, in addition large‐scale studies should investigate this matter in detail.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sato K, Kang WH, Saga K, et al Biology of sweat glands and their disorders. II. Disorders of sweat gland function. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;20: 713–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kux M. Thorasic endoscopic sympathectomy in palmar and axillary hiperhidrosis. Arch Surg 1978;113: 264–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schnider P, Binder M, Auff E, et al Double‐blind trial of botulinium. A toxin for the treatment of focal hyperhidrosis of palms. Br J Dermatol 1997;136: 548–552.DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.d01-1233.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schnider P, Binder M, Kittler H, et al A randomized, double‐blind, placebo controlled trial of botulinium A toxin for severe axillary hyperhidrosis. Br J Dermatol 1999;140: 677–680.DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Byrne J, Walsch N, Hederman WP. Endoscopic versus transaxillary thoracic electrocautery of the sympathetic chain for palmar and axillary hyperhidrosis. Br J Surg 1990;77: 1046–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Claes G, Gothberg C. Endoscopic transthorasic electrocautery of the sympathetic chain for palmar and axillary hyperhidrosis. Br J Surg 1991;78: 760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lin CC. Extend thoracoscopic T2‐sympathectomy in treatment of hyperhidrosis: Experience with 130 consequtive cases. J Laparoendoscopic Surg 1992;2: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Firestone L. Autonomic influences on cardiac function: Lessons from the transplanted (denervated) heart. Int Anaestesiol Clin 1989;27: 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aubert AE, Ramaekers D. Neurocardiology: The benefits of irregularity. The basis of methodology, physiology and current clinical applications. Acta Cardiol 1999;54: 107–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Task force of European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiololgy . Heart rate variability, standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation 1996;93: 1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wheller T, Watkins PJ. Cardiac denervation in diabetes. Br Med J 1973;4: 584–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moberg E. Objective methods for determining the functional value of sensibility in the hand. J Bone Joint Surg 1959;40B: 454–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iwase S, Ikade T, Kitazawa H, et al Altered response in cutaneous sympathetic outflow to mental and thermal stimuli in primary palmoplanter hyperhidrosis. J Auton Nerv Syst 1997;64: 65–73.DOI: 10.1016/S0165-1838(97)00014-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Noppen M, Herregodts P, Dendale PD, et al Cardiopulmonary exercise testing following bilateral thoracoscopic sympathicolysis in patients with essential hyperhidrosis. Thorax 1995;50: 1097–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kingma R, Ten Worrde BJ, Scheffer GJ, et al Thorasic symapthectomy: Effects on hemodynamics and baroreflex control. Clin Auton Res 2002;12: 35–42.DOI: 10.1007/s102860200008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernston GG, Bigger JT Jr, Eckberg DL, et al Heart rate variability: Origin, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology 1997;34: 623–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shih C, Wu J, Lin M. Autonomic dysfunction in palmar hyperhidrosis. J Auton Nerv Syst 1983;8: 33–43.DOI: 10.1016/0165-1838(83)90021-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Birner P, Heinzl H, Schindl M, et al Cardiac autonomic function in patients suffering from primary focal hyperhidrosis. Eur Neurol 2000;44: 112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Senard JM, Moreu MS, Tran MA. Blood pressure and heart rate variability in patients with essential hyperhidrosis. Clin Auton Res 2003;13: 281–285.DOI: 10.1007/s10286-003-0104-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]