Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation/flutter (AF) is a common complication of open heart surgery and ACC/AHA guidelines strongly recommend the use of prophylactic beta‐blockers (BB) for its prevention. Several recent studies, however, have failed to show the desired protective effects of BB against post–coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) AF. As the protocols of CABG, medical management of CAD (coronary artery disease) and demographic features of the patients undergoing open heart surgery have evolved significantly over the last two decades, we decided to perform a review of evidence from latest randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to confirm the efficacy of prophylactic BB.

Methods

We searched for RCTs comparing the efficacy of prophylactic BB versus placebo/control against post‐CABG AF. We limited our search to 1995 till present to reflect ongoing advancements in the protocols of CABG and the medical management of CAD. Initially, 34 trials were selected; however after certain exclusions only 10 RCTs were included in the final analysis.

Results

Prophylactic BB decreased the incidence of post‐CABG AF from 32.8% in the control group to 20% in the prophylactic group with risk ratio (RR) of 0.50 with 95% CI of 0.36–0.69, P value < 0.001. In a subgroup analysis, carvedilol appears to be superior to metoprolol for the prevention of postoperative AF.

Conclusions

Despite several limitations, this analysis confirms the efficacy of prophylactic BB against post‐CABG AF in this era. We recommend continuing perioperative BB in the open heart surgery patients in the absence of contraindications.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, beta‐blockers, prevention, CABG, meta‐analysis

Atrial fibrillation/flutter (AF) is the most common arrhythmia following coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) with or without valve surgery and it adds significantly to morbidity, cost, and length of stay associated with this procedure.1, 2 Postoperative AF may also identify a subset of patients with higher in‐hospital and long‐term mortality.1

The reported incidence of new onset post‐CABG AF in the absence of recommended prophylaxis is about 20–40% after CABG alone and up to 50% after valve surgery.2, 3, 4

Updated American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2006 guidelines strongly recommend preoperative or postoperative initiation of oral beta‐blocker (BB) therapy for the prevention of post‐CABG AF. Other recommended pharmacological prophylactic therapies include Amiodarone and Sotalol.5 The largest meta‐analysis to assess the efficacy of prophylactic BB against post‐CABG AF was performed by Crystal et al.6 (2002) and it included 27 randomized controlled trials (RCTs); 21 of which were conducted in 1980s, predating the latest advancements in the protocols of CABG and medical management of coronary artery disease (CAD). Thus, these results are heavily influenced by the earlier studies and might not reflect the true efficacy of prophylactic BB in the recent era. In addition, despite of recommended prophylaxis, few recent studies have failed to confirm the desired protective effects of BB against post‐CABG AF7, 8, 9 and its incidence is on the rise as compared to past few years.5

The protocols and techniques of CABG have evolved considerably over the last two decades with the most notable changes of introduction of off pump CABG (OP CABG), increase in the number of patients undergoing valve surgery, use of new methods for the induction of hypothermia and cardioplegia and increasing age of the patients undergoing open heart surgery. Similarly, recent evidence has suggested judicious use of certain perioperative medications like aspirin (ASA), statins, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) to decrease the risk of postoperative complications. Some of these new measures (OP CABG, use of statins, and ACEI) have been independently shown to minimize peri‐CABG inflammation resulting in lower incidence of postoperative arrhythmias including AF.4, 10, 11, 12 These findings along with few recent studies which did not confirm the desired AF protection have created certain doubts regarding the utility of prophylactic BB as some authors think that lower incidence of post‐CABG AF might be linked to the factors other than prophylaxis with BB.9

To further clarify the role of prophylactic BB in this era of new CABG protocols and to minimize the immeasurable confounding effects of recent advancements in the medical management, we strongly felt the need to redo a meta‐analysis from the latest RCTs.

In addition, we also wanted to find the answers to two key issues which were not addressed in the guidelines

To find the effect of timing of initiation of BB prophylaxis (preoperative vs. postoperative) on the incidence of post‐CABG AF and

To measure the differences among individual BB regarding the prevention of AF.

METHODS

Selection and Characteristics of Studies

The search was performed in accordance with the recommendations from Cochrane Collaboration using Cochrane CENTRAL database, MEDLINE database of National Library of Medicine, PUBMED and SCOPUS using the initial key terms of “Atrial fibrillation” “Cardiac surgery” and “Beta‐Blockers.” References from the initially identified articles were hand searched to find additional relevant trials. We also searched the abstract books and CD ROMS of annual scientific meetings of the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology to find additional relevant manuscripts. No language restrictions were applied.

We limited our search to 1995 until the present (June 2011) to reflect recent changes in the techniques and protocols of CABG and advancement in the medical management of CAD. The year 1995 was chosen for two main reasons: one is the introduction of OP CABG in late 90s13 and the second is the beginning of the wide spread use of peri‐CABG cardio‐protective medications (ASA, Statins and ACEI).

The data was gathered by two researchers (authors MFK and MRM) individually and compared at the end to resolve any discrepancies. Attempts were made to contact one author to get relevant data however desired information could not be retrieved.

Trials were carefully reviewed with particular attention to inclusion/exclusion criteria, method of randomization, exact timing of administration of postoperative and preoperative BB, definition of AF, continuity of telemetry during postoperative period and the duration of follow up and the end point of the studies.

RCTs (blinded or unblinded) in which the patients undergoing elective CABG and/or valve replacement were randomized to prophylactic pharmacological intervention with BB versus placebo/no prophylaxis where incidence of post‐CABG AF or supra‐ventricular tachycardia (SVT) was one of the primary outcome measure were selected. Trials with any combination of prophylactic agents/supplements, use of other antiarrhythmic drugs, and use of BB in both of the randomized arms alone or in combination with other pharmacological agents were excluded.

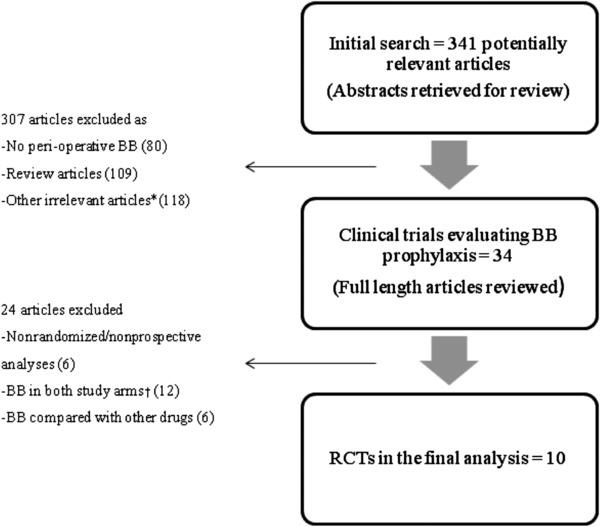

Initially, 34 manuscripts evaluating the efficacy of BB for the prevention of post‐CABG AF were identified, however 24 were excluded for various reasons (Fig. 1). The remaining ten RCTs were included in the final analysis.

Although most of the included RCTs have similar exclusion criteria (Absence of sinus rhythm at the time of surgery, atrioventricular (AV) block, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and bronchospasm, hypotension, and congestive heart failure (CHF), individual trials vary from one another in terms of definition of AF, length/method of monitoring and some demographic features of study population. Individual characteristics of included studies are detailed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the selection process *(including Risk factors for post‐CABG AF, treatment of AF, Letters to editor, noncardiac surgery patients). †(Two of these studies were used in a subanalysis).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Trials

| Name | Timing | Pre‐op BB% (P‐C) | Mean age (years) (P‐C) | Male% (P‐C) | LVEF (P‐C) | AF definition | Exclusion criteria | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imren et al. | PREOP | NA | 62.2–61.4 | 59–60 | 54–52 | 15 mins | CHF included | IOP Esmolol, OP CABG only |

| Lucio et al. | POSTOP | 65–63 | 59–62 | 72–74 | NA | Sustained symptom | EF<35% | Continuous ECG for only 3 days, BB WD |

| Wenke et al. | POSTOP | 61–56 | 63–64 | 79–75 | 63–62 | NK | EF<30% | BB WD, Continuous ECG for 2 days only |

| Paull et al. | POSTOP | NK | NK | NK | NK | 15 mins | EF<30% | No demographic information available |

| Yazicioglu et al. | PREOP | NA | 57–55 | 80–75 | 52–50 | NK | EF<30% | Small study group |

| Bert et al. | POSTOP | 76–72 | 63.6–63.8 | 76–83 | 49–49 | 5 mins | EF<20%, AVR included | BB WD |

| Connolly et al. | POSTOP | 82–79 | 63–62 | 78–80 | NK | 1 min | CHF, Valve surgery included | BB WD |

| Babin‐Ebell et al. | POSTOP | 61–65 | 61–64 | 76–83 | 67–62 | NK | EF<40% | BB WD, used SVT |

| Gun et al. | POSTOP | NK | NK | NK | NK | NK | NK | Only abstract is available |

| Ali et al. | POSTOP | 100–100 | 65–63 | 74–69 | 59–56 | NK | EF<35% | BB WD, Continuous ECG for 3 days only |

Abbreviations as in text. NS = nonspecific; NA = not applicable; NK = not known; min = minutes; IOP = intraoperative; OP = off‐pump; WD = withdrawal; P = prophylactic group, C = control group.

Statistical Analysis

We assessed publication bias by generating a funnel plot (not shown) and Begg's rank‐correlation method (Kendall's tau),14 using the “metabias” user‐written command in Stata 10.0. RR (Risk ratios) was the meta‐analytic measure of association, and was calculated using the number of subjects with AF and number of subjects in each trial group (2×2 tables). For the prospective trials which have a higher incidence of events in controls, use of RR is more appropriate than odds ratio (OR). Meta‐analyses were conducted on subgroups of studies involving different types of BB and were performed with the “metan” user‐written command in Stata 10.0. We tested statistical heterogeneity across trials with I2 values and Cochrane's Q statistic, using a P value greater than 0.10 to indicate presence of heterogeneity among trials for each analysis. However, we used a random effects model15 to estimate summary effects, which allows that the true effect could vary from study to study and assumes that the available studies are a random sample of the relevant distribution of effects.

RESULTS

The total number of patients studied in all of the included RCTs was 2556, of which 1280 comprised the prophylactic group and 1276 comprised the placebo group. The mean age of the study population ranged from 55 to 64 years. There was also an obvious male predominance anywhere from 60% to 80% in the individual studies.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Most of the authors,9, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23 except the two,19, 20 excluded patients with ejection fraction (EF) less than 20–40% and the mean EF of the study population ranged from 50% to 65%. Only two authors included the patients undergoing valve surgery.18, 19 Other standard exclusions were the contraindications to BB and prior CABG. Another important thing to notice is the use of pretrial BB; 60–100% of these patients were already talking preenrollment BB.16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22 Timing of initiation for BB prophylaxis was 3–4 days before the surgery in the preoperative prophylaxis studies20, 23 and within 24 hours of surgery in the postoperative group.9, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24 Definition of post‐CABG AF in terms of duration varied slightly among the trials. All the patients were monitored using continuous electrocardiography (ECG) or telemetry,9, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23 however, the duration of monitoring varied among individual studies.

Marked heterogeneity among the trials was largely explained by the use of different types and dosages of BB, variations in the sample size and use of prestudy BB. The quality of individual studies was assessed using Jaded score.25 Two studies had a score 5 each,19, 20 and the remaining eight9, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24 had a score of 3 each. A score of 3 was explained by the lack of double blindness due to a particular study design or yes/no nature of the outcome that is, AF. Funnel plots (Begg's method) were assessed visually and it displayed no asymmetry to suggest publication bias. Repeating the analysis excluding one trial24 which was reported only in the abstract form did not alter the overall results. Additional subgroup analyses measuring the effects of pre‐ and postoperative BB, metoprolol (MPL) and propranolol (PPL) against placebo resulted in similar results except for preoperative BB for which the protective effect did not appear statistically significant.

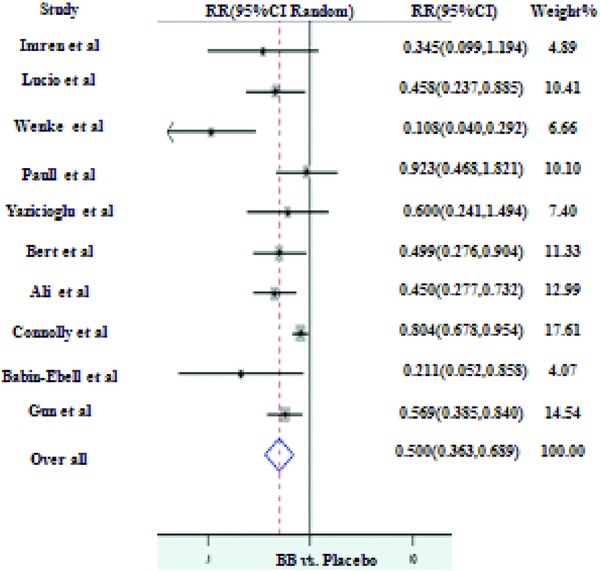

BB versus Placebo

Two hundred fifty‐eight of 1280 (20%) in the prophylactic group and 419 of 1276 (32.8%) in the control group developed new onset post‐CABG AF. The RR for the individual trials ranged from lowest of 0.11 to highest of 0.92 confirming the protective effect of BB against post‐CABG AF. This protective effect of BB was statistically significant in seven of ten RCTs. None of the trials showed increased incidence of post‐CABG AF with BB. Heterogeneity of the effect was indicated by (I2 = 67%, P = 0.001). Overall, patients on prophylactic BB had 50% reduced risk of developing post‐CABG AF (RR of 0.50, 95% CI 0.36–0.69 with P value < 0.001; Fig. 2). Repeating the analysis after excluding one trial24 resulted in similar values (RR of 0.48, 95% CI of 0.32–0.70 with P value < 0.001).

Figure 2.

BB prophylaxis versus placebo for the prevention of AF.

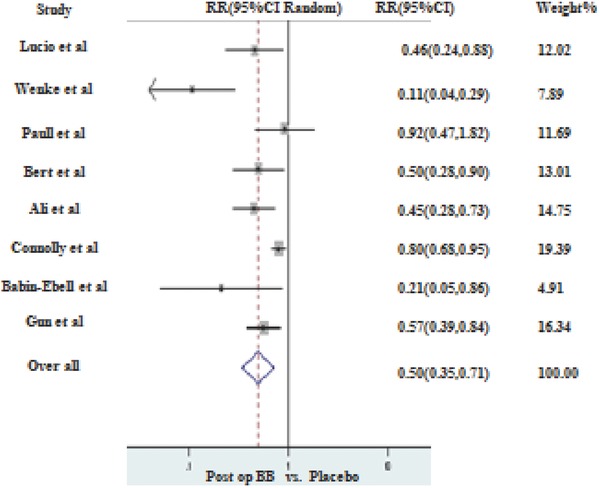

Preoperative versus Postoperative Initiation of Prophylaxis

Majority of the studies included in this analysis compared postoperative initiation of BB prophylaxis9, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24 with controls and only two authors studied the effects of preoperative initiation of prophylaxis.20, 23 Preoperative BB prophylaxis initiation (I2 = 0%, P = 0.48) resulted in 51% reduction in the incidence of AF as compared to controls, however these results were not statistically significant. (RR 0.49, 95% CI of 0.24–1.0 with P value = 0.06). On the other hand, in the postoperative initiation group (I2 = 73.4%, P < 0.001), BB reduced the incidence up to 50% with statistically significant P value (RR 0.50, 95% CI of 0.35–0.71 with P value < 0.001; Fig. 3). Sensitivity analysis for the postoperative group after excluding Gun et al.24 produced slightly stronger values (RR of 0.47, 95% CI of 0.303–0.732 with P value < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Postoperative BB prophylaxis versus placebo for the prevention of AF.

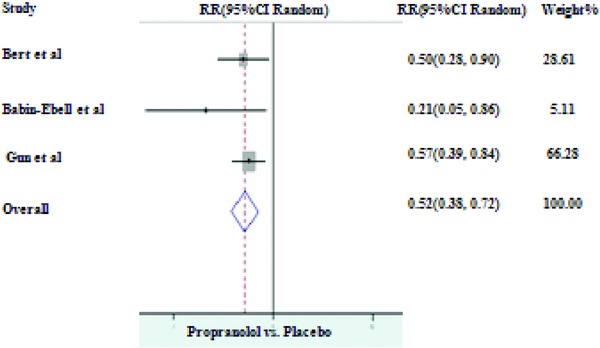

Efficacy of Different BB

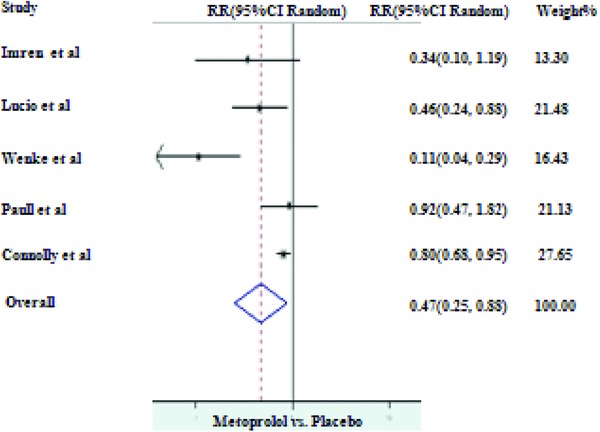

MPL was the most commonly used BB in RCTs after 1990s followed by PPL and atenolol (ATL). Comparison of different BB revealed that PPL and MPL were nearly equally effective in protecting against post‐CABG AF. As compared to controls, PPL (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.404) reduced the incidence of post‐CABG AF up to 48% (RR of 0.52, 95% CI of 0.38–0.72 with P value < 0.001; Fig. 4) whereas use of MPL (I2 = 79.2%, P = 0.001) as a prophylactic drug resulted in 53% reduction in the incidence of AF (RR of 0.47, 95% CI of 0.25–0.89 with P value < 0.001; Fig. 5). Repeat analysis for PPL group after excluding Gun et al.24 resulted in stronger protection (RR of 0.41, 95% CI of 0.20–0.83 with P value < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Prophylaxis with propranolol versus placebo for the prevention of AF.

Figure 5.

Prophylaxis with metoprolol versus placebo for the prevention of AF.

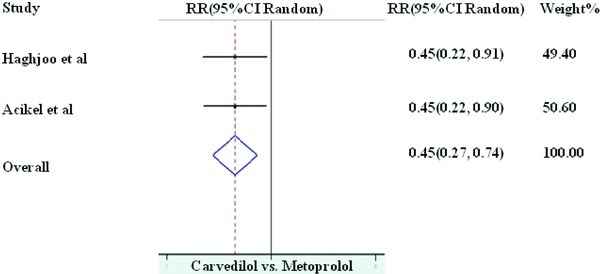

Although excluded from the initially selected RCTs, for the sake of comparison we included two randomized trials comparing MPL to carvedilol (CRG). In the meta‐analysis of two available studies;26, 27 as compared to MPL, CRG (I2 = 0.0%, P = 1.00) resulted in 55% reduction in the incidence of AF (RR 0.45, 95% CI of 0.28–0.74 with P value < 0.001; Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Prophylaxis with carvedilol versus metoprolol for the prevention of AF.

DISCUSSION

AF complicates up to 40% of the 500,000 patients per year undergoing CABG and increases the cost of the procedure by 10,055 per case resulting in incremental cost of about $2 billion annually.28 It also increases the length of stay to additional 4–5 days and identifies a subset of patients at increased risk of morbidity, strokes and in‐hospital and long‐term mortality.1, 4, 28 The results of our meta‐analysis are similar to those of previous analyses with few exceptions. First of all, of the pooled proportions, reported incidence of postoperative AF in the controls in two previous analyses was 34% and 33% 6, 29 which is similar to that found by us (32.8%). This similarity contradicts the verdict of recent increase in the incidence of post‐CABG AF mentioned in other articles.5 However, reported incidence of post‐CABG AF in the prophylactic group was 8.7% in Andrews et al.29 analysis as compared to 20% in this review. Andrews et al. included 18 RCTs (1549 patients) in their meta‐analysis and found, as compared to controls, BB prophylaxis reduced the likelihood of post‐CABG AF with OR = 0.28, 95% CI of 0.21–0.36. Similarly, Crystal et al.6 used 27 RCTs trials with 3840 patients and found reduced incidence of post‐CABG AF with BB prophylaxis with OR = 0.39, 95% CI of 0.28–0.52. If we had analyzed the OR, the summary results for all the studies would have been OR = 0.40, 95% CI of 0.27–0.60, indicating results similar to that of Crystal et al. but different from Andrews et al. The exact reason of this difference in the efficacy of BB remains unclear. Although there are several differences between the study populations of the two analyses, however one of the most notable differences is the mean age of the patients undergoing open heart surgery. The mean age range for the Andrews et al. analysis was 51–60 which is younger to current mean age range of 55–65. Age is one of the strongest risk factor for the development of post‐CABG AF and higher age of the patients undergoing open heart surgery accounts for higher risk for postoperative AF.4 However, despite of age difference between the two populations, incidence of post‐CABG AF is similar between the control groups. Does it mean that age adversely affect prophylactic ability of BB against post‐CABG AF? In our opinion, we need further work to clarify the relationship between age and efficacy of prophylactic BB against AF.

Although no previous trial directly compared AF prophylaxis between PPL and MPL, in a subgroup analysis we did not find significant difference between PPL (most commonly used BB in earlier studies) and MPL (most commonly used BB in the recent studies) regarding the protection against post‐CABG AF.

In a separate meta‐analysis of two randomized comparative studies,26, 27 CRG appears to be more effective than MPL for the prevention of post‐CABG AF; however, the number of patients in both of these studies are small. In addition to its usual alpha and beta blockade effects, CRG has been shown to exert antiinflammatory, anti‐oxidant, and anti‐arrhythmic actions in certain clinical settings.30, 31, 32 As the development of post‐CABG AF has been linked with higher levels of inflammation and oxidative stress in the peri‐operative period,33, 34, 35 it is possible that above mentioned properties of CRG might offer an additional protection against post‐CABG AF.

Based on the available information, it is difficult to evaluate the relationship between dosages of BB and the incidence of post‐CABG AF (Table 2). Two studies which titrated prophylactic BB dosages to heart rates of 60–90 per minute, did not find any correlation between higher dosages and prevention of post‐CABG AF.9, 21 Two other studies which showed the lowest incidence of post‐CABG AF among the included RCTs, only used low‐to‐moderate dosages of BB for prophylaxis.17, 22 On the other hand, in a study by Connolly et al., incidence of post‐CABG AF with BB prophylaxis was 31% even with moderately higher dosages of MPL (100 and 150 mg per day) and increasing the dose from 100 mg per day to 150 mg per day did not affect the outcome.19

Table 2.

Dosages of Drugs in Included Trials

| Study | Beta‐blocker | Dosages | Post‐ CABG AF in prophylactic arm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imren et al. | MPL | 50 mg daily | 8.8% |

| Lucio et al. | MPL | 100–300 mg daily (titrated) | 11% |

| Wenke et al. | MPL | 1 mg/kg | 4% |

| Paull et al. | MPL | 50–200 mg daily (titrated) | 24% |

| Yazicioglu et al. | ATL | 50 mg daily | 15.4% |

| Bert et al. | PPL | 40 (10 q6h) mg daily | 18% |

| Connolly et al. | MPL | 100–150 mg daily | 31% |

| Babin‐Ebell et al. | PPL | 40 (10 q6h) mg daily | 7% |

| Gun et al. | PPL | NK | 13.2% |

| Ali et al. | NS | NK | 17% |

NS = nonspecific; NK = not known.

Our data cannot be corrected to adjust for differences in the dosages of BB, and this difference in dosages among the studies, remains one of the main determinants of heterogeneity for this analysis. This issue gets further complicated by the fact that there are no RCTs comparing different dosages of same drug for the prevention of post‐CABG AF; and the studies which used titration of BB dosages to lower heart rates in the perioperative period did not show any convincing relationship between lower heart rates and incidence of post‐CABG AF.9, 21

Previous studies did not show statistically significant difference in protection against post‐CABG AF with regard to timing of initiation of prophylaxis.29 Based on our analysis, postoperative initiation of BB prophylaxis appears to be superior to preoperative initiation of prophylaxis for the prevention of post‐CABG AF. However, one must realize that this comparison is limited by relatively lower number of patients in the preoperative arm (151 in preoperative prophylaxis group vs. 2405 in postoperative prophylaxis group). We feel that this matter should be further investigated in RCTs to reach a final conclusion.

Most of the included studies9, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23 used a 24/7 telemetry or continuous ECG monitoring for arrhythmia detection which is in contrast to a previous analysis where many of the studies had used bed side monitoring resulting in potential bias of lower incidence of reported AF.29

Limitations

In addition to usual limitations of a meta‐analysis, there are several shortcomings to the results of this paper. One of the most prominent one pertaining to the individual studies is a comparison between group of patients who were continued on their pretrial BB therapy to those where BB were abruptly discontinued before or after the surgery, creating a BB withdrawal.16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22 Deleterious effects of BB withdrawal had been studied in details and are well‐known to cause AF.2, 4, 28, 36, 37 60–100% of patients (prophylactic and control groups) included in the selected RCTs were taking preenrollment BB. Patients with chronic BB therapy have a hyper adrenergic state due to up regulation of beta‐adrenergic receptors.38, 39, 40, 41 Abrupt discontinuation of BB results in rebound increase in sympathetic activity which may predispose to AF.37, 42, 43 In these studies, discontinuation of BB in the control group likely created a withdrawal effect resulting in increased incidence of postoperative AF. Thus, the final results are biased and at least partially represent the effects of BB withdrawal rather than true magnitude of protection offered by the prophylactic BB. This withdrawal effect is more prominent with agents of shorter half life like PPL44 and MPL which were the most commonly used drugs in the included RCTs. BB withdrawal phenomenon have been shown to last for 8–13 days,39 which means that even preoperative discontinuation of nonstudy BB in controls for at least 7 days before the surgery to enroll in RCT might have created withdrawal effects in the post‐CABG period. A previous meta‐analysis tried to overcome this issue by performing a subgroup analysis by dividing the available studies into two groups that is, those with and without BB withdrawal. “BB withdrawn” group consisted of the studies where study BB was compared to placebo plus discontinuation of nonstudy BB whereas “BB not withdrawn” group comprised of studies where study BB was compared to placebo plus continuation of nonstudy BB.45 Although authors showed that prophylactic BB appeared much less effective in the absence of withdrawal however these results were confounded as “BB not withdrawn” group had BB in both the arms (control and prophylactic) which would have underestimated the protection offered by prophylactic BB. In this article, we could not perform such an analysis as eight of the included trials were cofounded by withdrawal along with two trials where the information on the continuation of nonstudy BB was not clearly stated.

In addition, patients with CHF, COPD, past history of AF and combined CABG and valve surgery who were at higher risk for postoperative AF4 were excluded from many of the RCTs. Thus, these results cannot be generalized to nonstudy and higher risk patients.

We could not compare the efficacy of prophylactic BB between OP CABG versus conventional CABG as several RCTs, though included patients with OP CABG, did not separately describe the characteristics of two groups.

Although all of the studies used continuous ECG monitoring for arrhythmia detection, the duration of monitoring in some of the studies was only for 3 days.

Analysis is limited as we did not have access to all the clinically relevant information.

CONCLUSION

Although there are several limitations, results of this analysis represent the efficacy of prophylactic BB in open heart surgery patients of this era. By setting our starting point to 1995, we tried to minimize the confounding factors related to the evolution of protocols of CABG and the medical management of CAD.

We conclude that continuation of perioperative BB in patients without any contraindication to BB therapy is protective against post‐CABG AF. Although CRG appears to be a better prophylactic agent than MPL, we need further RCTs to confirm this finding.

To minimize the confounding effects of BB withdrawal, with current standards of care it is difficult to enroll CAD patients who are not taking any pretrial BB, however an RCT involving patients undergoing isolated valve surgery who are naive to BB will give a true measure of protection offered by BB against post‐CABG AF.

Acknowledgments

None.

Authors have no conflict of interest or any kind of relationship to the industry to be disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1. Villareal RP, Hariharan R, Liu BC, et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation and mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Creswell LL, Schuessler RB, Rosenbloom M, et al. Hazards of postoperative atrial arrhythmias. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maisel WH, Rawn JD, Stevenson WG. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:1061–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mathew JP, Fontes ML, Tudor IC, et al. A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Jama 2004;291:1720–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2006;114:e257–e354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crystal E, Connolly SJ, Sleik K, et al. Interventions on prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing heart surgery: A meta‐analysis. Circulation 2002;106:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balcetyte‐Harris N, Tamis JE, Homel P, et al. Randomized study of early intravenous esmolol versus oral beta‐blockers in preventing post‐CABG atrial fibrillation in high risk patients identified by signal‐averaged ECG: Results of a pilot study. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2002;7:86–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maniar PB, Balcetyte‐Harris N, Tamis JE, et al. Intravenous versus oral beta‐blockers for prevention of post‐CABG atrial fibrillation in high‐risk patients identified by signal‐averaged ECG: Lessons of a pilot study. Card Electrophysiol Rev 2003;7:158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paull DL, Tidwell SL, Guyton SW, et al. Beta blockade to prevent atrial dysrhythmias following coronary bypass surgery. Am J Surg 1997;173:419–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tomic V, Russwurm S, Moller E, et al. Transcriptomic and proteomic patterns of systemic inflammation in on‐pump and off‐pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation 2005;112:2912–2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wijeysundera DN, Beattie WS, Djaiani G, et al. Off‐pump coronary artery surgery for reducing mortality and morbidity: Meta‐analysis of randomized and observational studies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:872–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patti G, Chello M, Candura D, et al. Randomized trial of atorvastatin for reduction of postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: Results of the ARMYDA‐3 (Atorvastatin for Reduction of MYocardial Dysrhythmia After cardiac surgery) study. Circulation 2006;114:1455–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Plomondon ME, Cleveland JC, Jr. , Ludwig ST, et al. Off‐pump coronary artery bypass is associated with improved risk‐adjusted outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ali IM, Sanalla AA, Clark V. Beta‐blocker effects on postoperative atrial fibrillation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997;11:1154–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Babin‐Ebell J, Keith PR, Elert O. Efficacy and safety of low‐dose propranolol versus diltiazem in the prophylaxis of supraventricular tachyarrhythmia after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1996;10:412–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bert AA, Reinert SE, Singh AK. A beta‐blocker, not magnesium, is effective prophylaxis for atrial tachyarrhythmias after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2001;15:204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Connolly SJ, Cybulsky I, Lamy A, et al. Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomized trial of prophylactic metoprolol for reduction of hospital length of stay after heart surgery: The beta‐Blocker Length Of Stay (BLOS) study. Am Heart J 2003;145:226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Imren Y, Benson AA, Zor H, et al. Preoperative beta‐blocker use reduces atrial fibrillation in off‐pump coronary bypass surgery. ANZ J Surg 2007;77:429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucio Ede A, Flores A, Blacher C, et al. Effectiveness of metoprolol in preventing atrial fibrillation and flutter in the postoperative period of coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Arq Bras Cardiol 2004;82:42–46, 37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wenke K, Parsa MH, Imhof M, et al. Efficacy of metoprolol in prevention of supraventricular arrhythmias after coronary artery bypass grafting. Z Kardiol 1999;88:647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yazicioglu L, Eryilmaz S, Sirlak M, et al. The effect of preoperative digitalis and atenolol combination on postoperative atrial fibrillation incidence. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;22:397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gun C, Bianco AC, Freire RB, et al. Beta Blocker effects on postoperative atrial fibrillation after coronary artery by‐pass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol, CD‐ROM of abstracts from World Cardiology Congress. 3801; 1998.

- 25. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Acikel S, Bozbas H, Gultekin B, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of metoprolol and carvedilol for preventing atrial fibrillation after coronary bypass surgery. Int J Cardiol 2008;126:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haghjoo M, Saravi M, Hashemi MJ, et al. Optimal beta‐blocker for prevention of atrial fibrillation after on‐pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Carvedilol versus metoprolol. Heart Rhythm 2007;4:1170–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aranki SF, Shaw DP, Adams DH, et al. Predictors of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery surgery. Current trends and impact on hospital resources. Circulation 1996;94:390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andrews TC, Reimold SC, Berlin JA, et al. Prevention of supraventricular arrhythmias after coronary artery bypass surgery. A meta‐analysis of randomized control trials. Circulation 1991;84:236–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arumanayagam M, Chan S, Tong S, et al. Antioxidant properties of carvedilol and metoprolol in heart failure: A double‐blind randomized controlled trial. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2001;37:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. El‐Sherif N, Turitto G. Electrophysiologic effects of carvedilol: Is carvedilol an antiarrhythmic agent? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2005;28:985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yasunari K, Maeda K, Nakamura M, et al. Effects of carvedilol on oxidative stress in polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells in patients with essential hypertension. Am J Med 2004;116:460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bruins P, te Velthuis H, Yazdanbakhsh AP, et al. Activation of the complement system during and after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: Postsurgery activation involves C‐reactive protein and is associated with postoperative arrhythmia. Circulation 1997;96:3542–3548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Engelmann MD, Svendsen JH. Inflammation in the genesis and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2005;26:2083–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Korantzopoulos P, Kolettis TM, Galaris D, et al. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2007;115:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aytemir K, Aksoyek S, Ozer N, et al. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: P wave signal averaged ECG, clinical and angiographic variables in risk assessment. Int J Cardiol 1999;69:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Budeus M, Hennersdorf M, Rohlen S, et al. Prediction of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting: The role of chemoreflex‐sensitivity and P wave signal averaged ECG. Int J Cardiol 2006;106:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aarons RD, Molinoff PB. Changes in the density of beta adrenergic receptors in rat lymphocytes, heart and lung after chronic treatment with propranolol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1982;221:439–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boudoulas H, Lewis RP, Kates RE, et al. Hypersensitivity to adrenergic stimulation after propranolol withdrawal in normal subjects. Ann Intern Med 1977;87:433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Glaubiger G, Lefkowitz RJ. Elevated beta‐adrenergic receptor number after chronic propranolol treatment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1977;78:720–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG, Stiles GL. Mechanisms of membrane‐receptor regulation. Biochemical, physiological, and clinical insights derived from studies of the adrenergic receptors. N Engl J Med 1984;310:1570–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kalman JM, Munawar M, Howes LG, et al. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with sympathetic activation. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:1709–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Frost L, Molgaard H, Christiansen EH, et al. Low vagal tone and supraventricular ectopic activity predict atrial fibrillation and flutter after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur Heart J 1995;16:825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Krukemyer JJ, Boudoulas H, Binkley PF, et al. Comparison of hypersensitivity to adrenergic stimulation after abrupt withdrawal of propranolol and nadolol: Influence of half‐life differences. Am Heart J 1990;120:572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Burgess DC, Kilborn MJ, Keech AC. Interventions for prevention of post‐operative atrial fibrillation and its complications after cardiac surgery: A meta‐analysis. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2846–2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]