Abstract

Background: Chagas disease (ChD) patients might present chronotropic incompetence during exercise, although its physiopathology remains uncertain. We evaluated the heart rate (HR) response to exercise testing in ChD patients in order to determine the role of autonomic modulation and left ventricular dysfunction in the physiopathology of chronotropic incompetence.

Methods: ChD ambulatory patients (n = 170) and healthy controls (n = 24) underwent a standardized protocol including Doppler echocardiography, Holter monitoring, HR variability analysis, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) measurement, and maximal exercise testing. The chronotropic response was calculated as the percentage of predicted HR achieved and the HR increment (ΔHR) during exercise. ChD patients were divided according to the absence or presence of cardiopathy and chronotropic incompetence (<85% predicted HR).

Results: Chronotropic incompetence was present in 34 (20%) of all ChD patients. The group with cardiopathy displayed reduced ΔHR (91 ± 19 bpm) during exercise in comparison with ChD patients without cardiopathy (100 ± 19 bpm). Both the values observed in ChD groups were significantly different from those of controls (112 ± 13 bpm). Exercise duration, maximal oxygen consumption, and systolic blood pressure increment were significantly reduced in patients with abnormal chronotropic response. ΔHR during the exercise was significantly correlated with markers of autonomic control of sinus node, such as rest HR (r =−0.498, P ≤ 0.001), peak HR during exercise (r = 0.775, P ≤ 0.001), minimal HR during Holter recording (r =−0.231, P = 0.003), and high‐ and low‐frequency components of short‐term HR variability (r = 0.188, P = 0.042 and r = 0.203, P = 0.027). Neither left ventricular function nor BNP levels were independently related to the presence of chronotropic incompetence.

Conclusions: Chronotropic incompetence may be considered an early sign of autonomic dysfunction in ChD patients.

Keywords: Chagas disease, exercise test, chronotropic incompetence, autonomic nervous system, heart rate variability

Chagas disease (ChD) is caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi and represents one of the main causes of mortality in Latin America, where nearly 15 million individuals are infected. The disease has a high socioeconomic impact as a result of the infection of a relevant population contingent during their most productive years. The clinical course of ChD is quite variable; while some infected individuals develop fatal heart disease, others remain completely asymptomatic throughout life. 1 , 2

In their seminal study published in 1922, Chagas and Villela described a peculiar absence of chronotropic response to atropine in Chagas cardiopathy patients. 3 Further studies confirmed that ChD patients might present chronotropic incompetence during dynamic and isometric exercise 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 or dobutamine stress. 9 Nonetheless, the physiopathology of chronotropic incompetence in ChD is far from being elucidated. Left ventricular dysfunction, 10 parasympathetic dysfunction, 4 , 6 , 7 sympathetic denervation, 11 reduced circulating norepinephrine levels, 12 autoantibodies against β‐adrenergic receptors, 9 , 13 and sinus node dysfunction 13 are the factors that have been considered as possible determinants of the observed chronotropic incompetence. An additional point of interest derives from the fact that chronotropic incompetence is of negative prognostic significance in other clinical settings. 14

The objective of the present study was to assess the heart rate (HR) response to a standard treadmill exercise test in a large sample of ambulatory ChD patients in order to determine the role of autonomic heart control, studied by time and frequency‐domain analysis of HR variability, and left ventricular dysfunction (evaluated by echocardiography), in the physiopathology of chronotropic incompetence.

METHODS

Patient Population

Patients were recruited at the Chagas Disease Outpatient Center of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil, to which they were referred from blood banks or primary care services for the determination of suspected or confirmed infection with T. cruzi. A confirmed diagnosis of ChD on serological grounds was defined by the presence of two or more different positive reactions to T. cruzi (indirect immunofluorescence, enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay, or indirect hemagglutination). Patients who agreed to participate and signed a written informed consent were submitted to a standard screening protocol that included medical history, physical examination, ECG, laboratory examination, and chest roentgenogram. Exclusion criteria were (1) other systemic disorders, like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal or hepatic failure, anemia, and high blood pressure; (2) pregnancy; (3) alcoholism; (4) use of drugs that could compromise the chronotropic response in exercise testing; (5) chronic atrial fibrillation or pacemaker rhythm at basal ECG; and (6) exercise testing interruption due to technical or medical reasons (chest pain, dizziness, arrhythmia, and abnormal increase in blood pressure). The study population consisted of 170 ambulatory patients with confirmed serological findings of ChD and absence of other systemic disorders. A control group of 24 healthy volunteers aged 20–70 years with no risk or serological evidence of ChD was also submitted to the same evaluation.

Study Protocol

The Research Ethical Board of the Federal University of Minas Gerais approved the study protocol. Doppler echocardiographic features, 15 brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels, 16 and HR variability indices 17 of this population have been previously reported and other methodological aspects can be obtained in the cited articles. Patients underwent Doppler echocardiography with color flow using an ATL Philips HDI 5000 apparatus (Bothell, Washington, USA) operated by an experienced ecocardiographer (M.V.L.B.), blinded to the clinical status of the patients. 15 The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was obtained by Simpson's method using the software provided with the equipment. We measured BNP by radioimmunoassay (RIA, all samples in the same assay) using hBNP as standard, tyr0‐BNP for iodination, and a specific hBNP antibody (Peninsula Laboratories, USA), as previously described. 16

Twenty‐four‐hour Holter monitoring was performed using a portable three‐channel cassette tape recorder (Dynamis, Cardios, São Paulo, Brazil). Subjects were encouraged to continue with their normal everyday activities during the recordings, avoiding physical exercise or drugs that could interfere with autonomic function. Analysis of the tapes was performed when at least 18 hours of good quality tracings were available. The recordings were analyzed on a Burdick/DMI/Cardios Hospital Holter System (Spacelabs Burdick, Deerfield, Wisconsin/Cardios, São Paulo, Brazil) by a semiautomatic technique. Minimal, mean and maximal HR, the number of ectopic ventricular and supraventricular beats, and the occurrence of pauses and heart blocks were recorded. The following time‐domain HR variability indices were calculated 18 : standard deviation of R‐R intervals (SDNN) and square root of the mean of sum of squares of differences between adjacent R‐R intervals (rMSSD). Spectral analysis of HR variability was computed using Fast Fourier transformation (Burdick HRV software Spacelabs Burdick, Deerfield, Wisconsin, USA) and was expressed as total power (0.01–1.00 Hz) and low‐frequency (0.04–0.15 Hz) and high‐frequency (0.15–0.40 Hz) components. The low‐to‐high frequency component ratio (LF/HF) was also calculated. 18 , 19 In order to minimize nonstationary oscillations of HR variability, spectral analysis was performed during sleep, in a 5‐minute segment of good quality and without ectopic beats, close to the lowest HR. For technical reasons, frequency‐domain analysis was performed only in the last 115 consecutive patients with ChD.

A maximal stress test was performed according to the standard Bruce protocol. 20 Patients were encouraged to exercise until they reached their maximal effort. HR and blood pressure were measured at rest, during each stage of exercise, at peak exercise, and during recovery. Exercise capacity as estimated maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) was calculated based on a previously published normogram. 20 Subjects were not credited with achieving any given stage of exercise unless they reached the point when blood pressure was measured, namely, 2 minutes into that stage. Patients who could not achieve maximal effort due to medical or technical reasons were not included in this study since they could be erroneously classified as having chronotropic incompetence even if the stress testing was interrupted by arrhythmias or dizziness. The characteristics studied included resting HR, peak HR, peak–rest HR increment (ΔHR) during exercise test, percent of age‐predicted HR achieved, peak systolic blood pressure, effort‐induced systolic blood pressure increment, estimated VO2 max, double product, and the presence of arrhythmias.

ChD and control subjects were compared according to general features and HR response to exercise. For these comparisons, ChD patients were divided into two groups according to the presence (group II) or absence (group I) of at least one of the typical evidences of Chagas cardiopathy, 2 defined as (1) III or IV NYHA functional class; (2) ECG abnormalities including 2nd or 3rd degree atrioventricular or intraventricular blocks, abnormal Q wave, >1 ventricular ectopic beat per tracing, low voltage QRS in standard leads; (3) cardiothoracic index >0.50; and (iv) LVEF <40% or presence of ventricular aneurysms.

For further analysis, ChD patients were divided into two groups according to the presence (group B) or absence (group A) of chronotropic incompetence, defined as the inability to achieve at least 85% of the predicted HR according to Astrand's formula (220‐age) at peak exercise. 14 General features, BNP levels, left ventricular function variables, HR variability indices, and exercise test features were compared between the two groups and correlated with the peak–rest ΔHR during exercise test, considered here as an index of chronotropic competence.

Statistical Analysis

Data obtained from continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median with the interquartile range. Pearson's or Spearman's correlation coefficients were used to measure correlation between variables. When necessary, mathematical transformation of nonnormal or heteroscedastic data was performed to allow subsequent analysis. Baseline features and transformed indices for the groups were compared by Student's t‐test or Wilcoxon test, when appropriate. Since the age was significantly correlated with many indices studied in multiple linear regression models, covariance analysis (ANCOVA) was used when necessary. In the ChD group, univariate and multivariate analysis were performed considering ΔHR during exercise test as dependent variable, and age, ejection fraction, HR before stress test, Holter and HR variability indices, and BNP as independent variables. Data concerning categorical variables were expressed as proportions and were compared by the chi‐square test for 2 × k contingence tables. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

ChD patients were slightly older than controls but with similar gender distribution (Table 1). ChD patients with cardiopathy (group II) achieved smaller estimated VO2 max and blood pressure increment during effort in comparison to controls. Effort‐induced ventricular ectopic beats were more frequent in ChD patients than in controls. When comparing group I and group II patients, ventricular ectopies were significantly more frequent also in patients with cardiopathy.

Table 1.

General Characteristics of Controls and Patients with Chagas Disease

| Variable Group | Controls n = 24 | Chagas I n = 52 | Chagas II n = 118 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35.6 ± 9.3 | 39.8 ± 9.0 | 41.8 ± 9.2 | 0.004 | 0 = 1 < 2 |

| Femalea (n (%)) | 7 (29) | 21 (40) | 52 (44) | 0.397 | |

| LVEFb (%) | 64 (61–66) | 62 (60–65) | 60 (50–64) | 0.001 | 0 = 1 > 2 |

| Ln BNP values (pg/mL) | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 0.004 | 0 = 1 < 2 |

| Estimated VO2max mL/kg per min | 49.4 ± 10.1 | 45.8 ± 10.6 | 44.2 ± 8.6 | 0.033c | 0=1, 1=2, 0>2c |

| ΔSystolic BP (mmHg) | 55.8 ± 12.8 | 48.2 ± 16.4 | 43.0 ± 21.1 | 0.015c | 0 = 1, 1 = 2, 0 > 2c |

| Rest HR (bpm) | 71 ± 13 | 70 ± 12 | 71 ± 12 | 0.793c | |

| ΔHR (bpm) | 112 ± 13 | 100 ± 19 | 91 ± 19 | <0.001c | 0 > 1 > 2c |

| % Maximal age‐predicted HRb | 101 (98–104) | 96 (90–99) | 85 (85–96) | <0.001 | 0 > 1 > 2 |

| Chronotropic incompetencea (n (%)) | 0 | 5 (9.6) | 29 (24.6) | 0.003 | 0 = 1 < 2 |

| Effort‐induced VPCa (n (%)) | 4 (17) | 23 (44) | 68 (58) | 0.001 | 0 < 1 < 2 |

Values were expressed as mean ± SD when appropriate, except awhen expressed as proportions; bwhen expressed as medians (interquartile range); cadjusted for age. HR = heart rate; bpm = beats per minute; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; VO2 max = maximal oxygen consumption; BP = blood pressure; Δ systolic BP = peak–rest BP; ΔHR = peak–rest HR increment; chronotropic incompetence = inability to achieve at least 85% of the age‐predicted HR; VPC = ventricular premature beats.

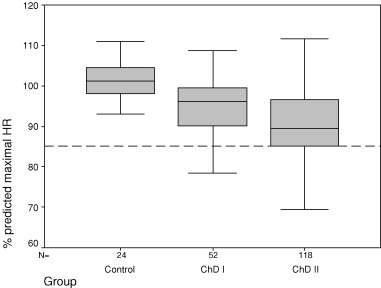

Although mean HR before stress testing was not different among groups, ΔHR at the end of maximal exercise was reduced in both the ChD groups and was more pronouncedly reduced in group II. Chronotropic incompetence, defined as inability to achieve at least 85% of the age‐predicted HR, was detectable only in ChD patients: 5 in group I (9.6%) and 29 in group II (24.6%, P = 0.003, Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Percent of age‐predicted HR increment achieved during exercise test in controls and Chagas disease patient groups I and II.

Among the 170 ChD patients studied, 34 (20%) failed to achieve 85% of the age‐predicted maximum HR and were assigned to group B (patients with chronotropic incompetence). Group A consisted of 136 (80%) patients without chronotropic incompetence. General and echocardiographic features and BNP levels were similar between groups (Table 2). LVEF values were slightly reduced in the group with chronotropic incompetence (group B). Exercise duration, VO2 max, and systolic blood pressure increment during the exercise were significantly reduced in patients with abnormal chronotropic response (Table 2). HR and HR variability indices were not significantly different between patients with and without chronotropic incompetence (Table 3). Ventricular ectopic beats during Holter monitoring were more frequent in group B patients.

Table 2.

General and Echocardiographic Features of Chagas Disease Patients with (group B) and without (group A) Chronotropic Incompetence

| Variable Group | A n = 136 | B n = 34 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.7 ± 9.5 | 42.1 ± 8.2 | 0.866 |

| Femalea (n (%)) | 59 (43) | 14 (41) | 0.849 |

| Right BBBa (n (%)) | 33 (24) | 12 (35) | 0.278 |

| LVEF† (%) | 62 (57–65) | 59 (50–62) | 0.020 |

| LV diastolic dimensionb (mm) | 50 (48–55) | 53 (48–56) | 0.153 |

| Diastolic dysfunctiona (n (%)) | 15 (11) | 6 (17) | 0.395 |

| LV wall motion scoreb (mm) | 1.00 (1.00–1.31) | 1.09 (1.00–1.86) | 0.187 |

| LV aneurysma (n (%)) | 25 (18) | 8 (23) | 0.447 |

| BNPb (pmol/L) | 38.7 (28.0–50.9) | 40.7 (32.7–49.4) | 0.280 |

| ΔSystolic BP (mmHg) | 47 ± 19 | 34 ± 19 | 0.001 |

| Duration of exerciseb (s) | 772 (621–886) | 621 (570–785) | 0.002 |

| Estimated VO2 maxb (mL/kg per min) | 45 (37–51) | 37 (35–46) | 0.003 |

Values were expressed as mean ± SD when appropriate, except awhen expressed as proportions; bwhen expressed as medians (interquartile range). BBB = right bundle branch block; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LV = left ventricular; BNP = brain natriuretic peptide; s = seconds, BP = blood pressure; Δsystolic BP= peak–rest BP; VO2 max = maximal oxygen consumption.

Table 3.

Holter Monitoring and Heart Rate Variability Indices in Chagas Disease Patients with (group B) and without (group A) Chronotropic Incompetence

| Variable Group | A n = 136 | B n = 34 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 24‐hour HR (bpm) | 74 ± 9 | 71 ± 12 | 0.251 |

| Maximal 24‐hour HR (bpm) | 135 ± 18 | 130 ± 14 | 0.203 |

| Minimal 24‐hour HR (bpm) | 48 ± 7 | 48 ± 9 | 0.845 |

| SDNNa (ms) | 152 (120–173) | 144 (111–200) | 0.244 |

| RMSSDa (ms) | 29 (23–40) | 35 (21–49) | 0.421 |

| VPCa (n/24 hour) | 33 (3–713) | 393 (13–3078) | 0.005 |

| Mean RR (spectral analysis)a (ms2) | 1040 (963–1127) | 990 (941–1123) | 0.484 |

| HFa (ms2) | 333 (150–567) | 183 (104–561) | 0.775 |

| LFa (ms2) | 470 (308–968) | 386 (203–1598) | 0.685 |

| LF/HFa | 1.82 (0.92–3.22) | 1.88 (0.46–4.6) | 0.639 |

Values were expressed as mean ± SD when appropriate, except awhen expressed as medians (interquartile range). HR = heart rate; bpm = beats per minute; SDNN = standard deviation of normal R‐R intervals; RMSSD = root mean square of successive differences; VPC = ventricular premature beats; HF = high frequency; ms2= milliseconds squared; LF = low frequency; LF/HF = LF/HF ratio.

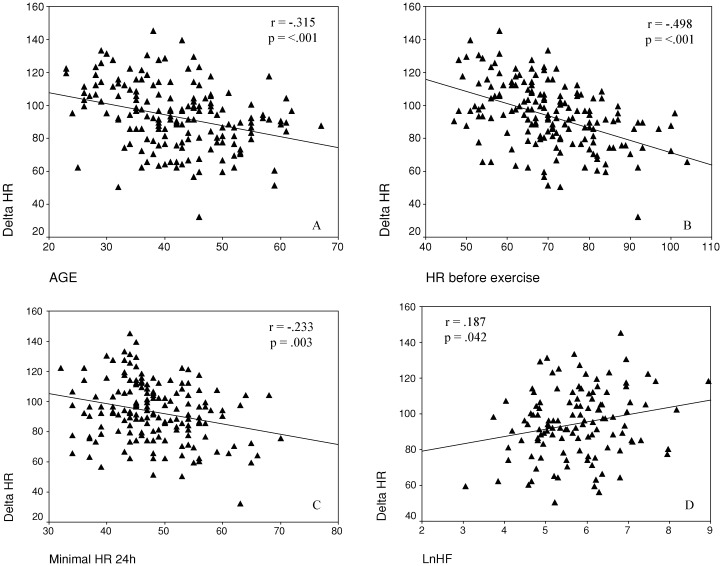

Correlation analysis showed significant correlations (Table 4) between ΔHR during exercise test and the following parameters: age (Fig. 2A), HR before the exercise (Fig. 2B), peak HR at the end of the exercise, minimal HR during 24‐hour Holter recording (Fig. 2C), and both high‐ and low‐frequency components of short‐term HR variability (Fig. 2D). In multivariate analysis, HR before and at the peak of the exercise were the independent predictors of the chronotropic response. LVEF was marginally correlated to ΔHR. Ventricular premature beats number in 24 hours was well correlated with ΔHR (rs =−0.238, P = 0.002). Both parameters did not remain significant predictors of chronotropic incompetence after multivariate analysis.

Table 4.

Correlation Coefficients among Peak–Rest HR Increment (ΔHR) During Exercise Test and Age, Ejection Fraction, Rest HR Before and at the Peak of the Exercise, HF and LF Components of Spectral Analysis, and Minimal, Mean, and Maximal HR During 24‐hour Holter in 170 Chagas Disease Patients

| Age | EF | HR Resting | HR Peak | Minimal 24‐Hour HR | Maximal 24‐Hour RR | LnHF | LnLF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔHR | −0.315 | 0.134a | −0.498 | 0.775 | −0.231 | 0.095 | 0.188 | 0.203 |

| P = 0.000 | P = 0.086 | P = 0.000 | P = 0.000 | P = 0.003 | P = 0.226 | P = 0.042 | P = 0.027 |

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of peak–rest HR increment (ΔHR) during exercise test and age (A), HR before stress test (B), minimal HR during 24‐hour Holter monitoring (C), and High‐frequency component of spectral analysis (D) in 170 Chagas disease patients.

DISCUSSION

Although chronotropic incompetence is a recognized feature of ChD, its pathogenesis remains uncertain.

Patients with chronotropic incompetence exhibited a significantly impaired exercise capacity, as reflected by a reduced duration of exercise and VO2 maxin comparison to ChD patients with a normal HR response. The prevalence of chronotropic incompetence was 20% in this clinic‐based sample, composed of ambulatory patients referred from blood banks or primary care services, generally with normal milder forms of the disease. This prevalence, however, could underestimate the real incidence of this phenomenon, since patients who interrupted their tests because of symptoms and for medical reasons were excluded from the study.

Chronotropic incompetence has been for long considered a factor that limits the exercise capacity of heart failure patients. 21 , 22 Moreover, in an asymptomatic population‐based cohort, the presence of chronotropic incompetence was predicted by increased cavity size and, among men, by depressed systolic function. 23 Since left ventricular dysfunction is a major feature of Chagas cardiopathy, it could be hypothesized that chronotropic incompetence might be secondary to depressed left ventricular systolic performance in ChD. In this study,we found a limited correlation between LVEF and chronotropic response which, however, was no longer significant at multivariate analysis. Moreover, BNP levels, an indirect marker of neurohumoral activation in ChD patients with depressed ventricular function, 16 were also not correlated with HR response to exercise. Both findings make this hypothesis unlikely.

Abnormal HR response to effort has been attributed to autonomic dysfunction in heart failure 21 and ChD. 4 , 7 Gallo et al. 4 , 7 showed, in a small number of ChD patients, a lower HR increase at a 5‐minute treadmill protocol, as well as abnormal HR response to atropine and Valsalva maneuver. 4 In a subsequent study, the same authors found that Chagas cardiopathy patients had a lower HR response during the initial 10 seconds of discontinuous dynamic exercise on a bicycle ergometer in comparison with control subjects. 7 Both findings were considered to reflect an abnormal vagal modulation, which was particularly evident during the initial phases of exercise, when vagal withdrawal is likely to occur. At variance with our findings, Gallo and coworkers did not find differences in VO2 max and other metabolic responses to long‐term exercise among groups. Indeed, some discordant findings may be explained by the different designs and aims of the studies. Gallo and coworkers performed physiological studies in small groups of patients in order to evaluate the functional conditions of the two divisions of the autonomic nervous system. We performed a clinic‐based study using a standard treadmill protocol with the objective of recognizing the determinants of chronotropic incompetence in ChD.

In the present study, we observed a positive correlation between HR increase induced by exercise and most of the HR and HR variability parameters that reflect vagal modulation. ΔHR was significantly correlated with HR before exercise and minimal nocturnal HR during Holter recording. Moreover, there was a correlation between ΔHR and low‐ and high‐frequency components of HR variability measured on a nocturnal 5‐minute period, when spectral components are likely to reflect the prevailing parasympathetic modulation. Thus, patients with evidence of a preserved vagal modulation of sinus node function displayed the maximum increase of HR during exercise, whereas patients with signs of reduced vagal modulation exhibited chronotropic incompetence. The strong correlation between age and ΔHR also supported the concept that a preserved autonomic innervation was a major determinant of a physiological chronotropic response to exercise.

The significant correlation between ΔHR and peak HR at the end of exercise, as well as low‐frequency component of HR variability was consistent with the hypothesis that a preserved sympathetic innervation is also likely to play a critical role. Regarding this latter point, it may be relevant to recall that, in this study, ChD patients with chronotropic incompetence also displayed blunted systolic blood pressure response, which could be related to abnormal sympathetic influence. Indeed, Iosa et al. 12 described reduced norepinephrine levels in heart failure patients with ChD compared to patients with heart failure of other etiologies, although these observations were not confirmed in a subsequent study. 24 Regional cardiac sympathetic denervation was also observed early in the course of Chagas cardiomyopathy by iodine‐123 meta‐iodobenzylguanidine cardiac scans. 25 Several studies have shown the existence of circulating antibodies that bind to β‐adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in ChD. 13 , 26 The deposited autoantibodies behaving as agonists could induce desensitization and/or down‐regulation of the receptors and lead to a progressive receptor blockade, determining a partial sympathetic and parasympathetic denervation. Indeed, postsynaptic desensitization of the β‐adrenergic receptor has been proposed as a mechanism of attenuated HR response to exercise in heart failure patients 22 and cannot be excluded in ChD patients.

The presence of an abnormal autonomic modulation in ChD patients is an established finding. In previous studies, we 17 , 27 , 28 and others 29 reported that this alteration was independent of the presence of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction. In this study, we observed that chronotropic incompetence could also be present in ChD patients without cardiopathy and was not directly related to the presence of LV dysfunction or indirect signs of neurohumoral activation. Indeed, most patients with and without chronotropic incompetence had normal indices of LV systolic and diastolic function and dimension. Nonetheless, chronotropic response was more profoundly depressed in patients with signs of cardiac involvement; in these subjects, a blunted systolic blood pressure response and a greater number of effort‐induced ventricular ectopic beats were also observed. All these findings could be interpreted as an indirect evidence of a more extensive derangement of cardiac function and regulatory mechanisms.

Some limitations of the present study should be pointed out. Pharmacological evaluation of the sinus node function was not performed and subclinical form of sinus sick syndrome cannot be excluded. Our results cannot be generalized to ChD patients with more severe heart disease, since we excluded from this study those with atrial fibrillation, pacemaker rhythm as well as those that could not achieve maximal effort due to serious symptoms or ECG abnormalities. Chronotropic incompetence was arbitrarily defined as the inability to achieve at least 85% of the predicted HR, a criterion that has been proposed and used by others. 14 Frequency‐domain analysis of HR variability was performed using commercial equipment in a 5‐minute segment close to the lowest HR during sleep to better evaluate vagal modulation and to avoid nonstationarity that could hamper spectral analysis. Additional information on autonomic control mechanisms could have been obtained by analyzing recordings collected in laboratory settings, especially during controlled breathing 30 or tilt test. 18

In conclusion, 20% of ChD patients in a clinic‐based sample presented chronotropic incompetence, which significantly impaired the exercise capacity, but was not directly related to LV dysfunction. Presence of a physiological autonomic modulation was a major determinant of a preserved chronotropic response to exercise. Chronotropic incompetence may be considered an early sign of autonomic dysfunction in ambulatory ChD patients.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: This study was supported by grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), Coordenadoria de Aperfeiçcoamento do Ensino Superior (CAPES), from Brazil, and Consiglio Nazionale delle Richerche (CNR), from Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carrasco HA, Parada H, Guerrero L, et al Prognostic implications of clinical, electrocardiographic and hemodynamic findings in chronic Chagas disease. Int J Cardiol 1994;43: 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rocha MO, Ribeiro AL, Teixeira MM. Clinical management of chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy. Front Biosci 2003;8: E44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chagas C, Villela E. Forma cardíaca da Trypanosomiase Americana. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1922;14: 5–61. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gallo L Jr, Neto JA, Manco JC, et al Abnormal heart rate responses during exercise in patients with Chagas disease. Cardiology 1975;60: 147–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pereira MH, Brito FS, Ambrose JA, et al Exercise testing in the latent phase of Chagas disease. Clin Cardiol 1984;7: 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marin‐Neto JA, Maciel BC, Gallo Junior L, et al Effect of parasympathetic impairment on the haemodynamic response to handgrip in Chagas heart disease. Br Heart J 1986;55: 204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gallo L Jr, Morelo Filho J, Maciel BC, et al Functional evaluation of sympathetic and parasympathetic system in Chagas disease using dynamic exercise. Cardiovasc Res 1987;21: 922–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ribeiro ALP, Tostes VTV, Torres RM, et al Teste ergométrico em chagásicos sem cardiopatia aparente. Arq Bras Cardiol 1995;5(Suppl.):96. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Acquatella H, Perez JE, Condado JA, et al Limited myocardial contractile reserve and chronotropic incompetence in patients with chronic Chagas disease: Assessment by dobutamine stress echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33: 522–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davila DF, Donis JH, Navas M, et al Response of heart rate to atropine and left ventricular function in Chagas heart disease. Int J Cardiol 1988;21: 143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simoes MV, Pintya AO, Bromberg‐Marin G, et al Relation of regional sympathetic denervation and myocardial perfusion disturbance to wall motion impairment in Chagas cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2000;86: 975–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iosa DJ, Dequattro V, Lee DD, et al Plasma norepinephrine in Chagas cardioneuromyopathy: A marker of progressive dysautonomia. Am Heart J 1989;117: 882–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chiale PA, Ferrari I, Mahler E, et al Differential profile and biochemical effects of antiautonomic membrane receptor antibodies in ventricular arrhythmias and sinus node dysfunction. Circulation 2001;103: 1765–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lauer MS, Okin PM, Larson M, et al Impaired heart rate response to graded exercise. Implications of chronotropic incompetence in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1996;93: 1520–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barros MV, Ribeiro AL, Machado FS, et al Doppler tissue imaging to assess systolic function in Chagas disease. Arq Bras Cardiol 2003;80: 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ribeiro ALP, Reis AM, Barros MVL, et al Brain natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of systolic left ventricular dysfunction in Chagas disease. Lancet 2002;360: 461–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ribeiro AL, Lombardi F, Sousa MR, et al Power‐law behavior of heart rate variability in Chagas disease. Am J Cardiol 2002;89: 414–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Cardiac Pacing and Electrophysiology . Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation 1996;93: 1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lombardi F. Clinical implications of present physiological understanding of HRV components. Card Electrophysiol Rev 2002;6: 245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Froelicher VF, Myers J. Exercise and the Heart, 4th Edition Philadelphia , Saunders, 2000, p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fei L, Keeling PJ, Sadoul N, et al Decreased heart rate variability in patients with congestive heart failure and chronotropic incompetence. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1996;19: 477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Colucci WS, Ribeiro JP, Rocco MB, et al Impaired chronotropic response to exercise in patients with congestive heart failure: Role of postsynaptic beta‐adrenergic desensitization. Circulation 1989;80: 314–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lauer MS, Larson MG, Evans JC, et al Association of left ventricular dilatation and hypertrophy with chronotropic incompetence in the Framingham Heart Study. Am Heart J 1999;137: 903–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bestetti RB, Coutinho‐Netto J, Staibano L, et al Peripheral and coronary sinus catecholamine levels in patients with severe congestive heart failure due to Chagas disease. Cardiology 1995;86: 202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Simoes MV, Pintya AO, Bromberg‐Marin G, et al Relation of regional sympathetic denervation and myocardial perfusion disturbance to wall motion impairment in Chagas cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2000;86: 975–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sterin‐Borda L, Borda E. Role of neurotransmitter autoantibodies in the pathogenesis of chagasic peripheral dysautonomia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;917: 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ribeiro AL, Moraes RS, Ribeiro JP, et al Parasympathetic dysautonomia precedes left ventricular systolic dysfunction in Chagas disease. Am Heart J 2001;141: 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oliveira E, Ribeiro AL, Assis Silva F, et al The Valsalva maneuver in Chagas disease patients without cardiopathy. Int J Cardiol 2002;82: 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marin‐Neto JA, Bromberg‐Marin G, Pazin‐Filho A, et al Cardiac autonomic impairment and early myocardial damage involving the right ventricle are independent phenomena in Chagas disease. Int J Cardiol 1998;65: 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. La Rovere MT, Pinna GD, Maestri R, et al Short‐term heart rate variability strongly predicts sudden cardiac death in chronic heart failure patients. Circulation 2003;107: 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]