Abstract

Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2011;16(3):303–307

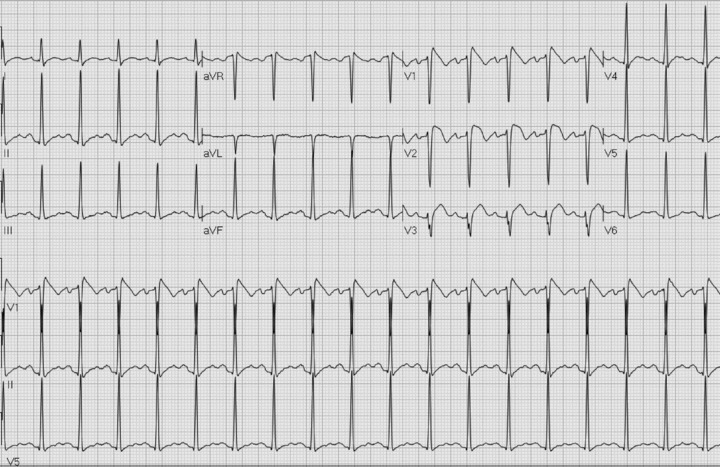

A 40‐year‐old male from the Dominican Republic presented to the emergency department with chief complaints of fever, sore throat, nausea, and emesis. His temperature on arrival was 39.3°C, pulse was 130 bpm, and blood pressure 134/83 mmHg. He denied shortness of breath, chest pain, or palpitations. His medical history was significant for hypertension treated with olmesartan, a bicuspid aortic valve with mild aortic stenosis, and asthma treated with albuterol. The patient rarely drank alcohol and denied use of tobacco. Laboratory tests showed a mild leukocytosis, normal electrolytes, and negative cardiac enzymes. An electrocardiogram (ECG) performed in the emergency department is shown in Figure 1. Cardiology was consulted for possible ST‐segment myocardial infarction, and the on call cardiologist decided to admit the patient for telemetry monitoring.

Figure 1.

ECG on presentation to emergency department with fever of 39.3°C.

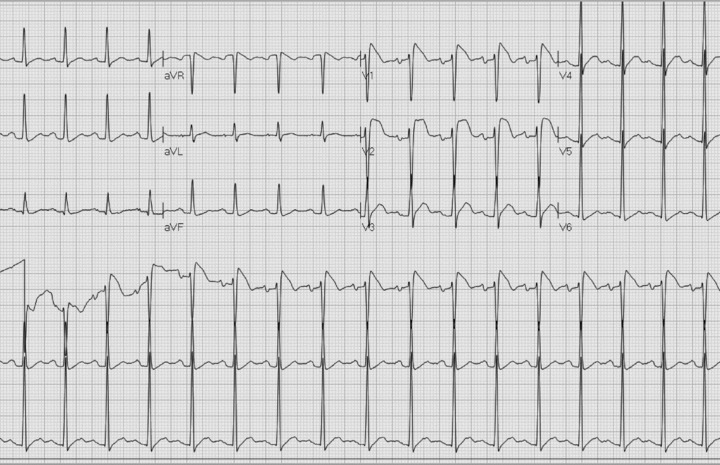

The following day, the patient remained febrile with worsening oropharyngeal discomfort. A CT scan of the head and neck revealed enlargement of the tonsils bilaterally, consistent with tonsillitis, and treatment with antibiotics was initiated. The ECG on second hospitalization day is shown in Figure 2; and follow‐up ECGs on days 3 and 5 of hospitalization, when the patient was fever free, are shown in Figures 3A and B, respectively.

Figure 2.

ECG on day 2. Fever of 38.9°C.

Figure 3.

(A) ECG on day 3. Temperature 37.1°C.

Figure 3.

(B) Predischarge ECG. Fever free for 72 hours.

Dr. Priori: Please comment on your initial thoughts regarding the electrocardiographic presentation of this patient. What would recommendations would you make for additional workup and management in light of this presentation?

The ECG shows ST segment elevation with a coved morphology, often referred to as a Brugada Type I ECG pattern. Other abnormalities typical of the ECG of Brugada patients are not present; in fact the PR and the QRS are not prolonged. The onset of the typical pattern with fever is a known manifestation in some patients with Brugada syndrome and it regresses as expected after reduction of body temperature. The patient is not on medications that are known to induce the Brugada ECG patterns. We would proceed with provocative drug test (flecainide or procainamide) to demonstrate that it is possible to induce the type I pattern and therefore confirm the diagnosis.

Prior to discharge, the cardiac electrophysiology service was consulted. The patient had no history of palpitations, presyncope or syncope, and no family history of sudden cardiac death. There were no family members in the United States to assess for Brugada pattern ECG. The patient underwent electrophysiology (EP) testing, during which triple extra‐stimuli induced ventricular flutter. The patient did not undergo genetic testing due to lack of insurance coverage. Based on the ECG presentation the patient was diagnosed with Brugada syndrome and a defibrillator was implanted for prevention of cardiac arrest. At the two‐year follow‐up, the patient has had no arrhythmic events.

Dr. Priori: Please comment on your opinion regarding the diagnostic and management strategies in this case.

We agree with the diagnosis. However, the use of programmed electrical stimulation as a risk stratifier in asymptomatic Brugada patients is controversial and I would not recommend it in this case: most of the studies and meta‐analysis today fail to show that programmed electrical stimulation is predictive of events at follow‐up. It would be important to know if the patient has ever experienced a syncopal events, assuming that he never had syncope, we would consider the patient as an individual with an intermediate risk for cardiac events based on a spontaneous (associated with fever) type I ECG pattern and lack of syncopal events. I would probably recommend no internal cardioverter‐defibrillator (ICD). There are preliminary data suggesting that quinidine may be protective in Brugada patients and therefore this therapy can also be considered. This drug is thought to exert its beneficial effects in Brugada syndrome by inhibiting Ito, thereby restoring electrical homogeneity. Regardless of the decision to initiate medical therapy, careful clinical follow‐up for symptoms is very important in this case.

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The typical ECG presentation during a febrile illness in a 40‐year‐old asymptomatic male is consistent with Brugada syndrome. This case presents a challenging management scenario since risk stratification and therapeutic approach in asymptomatic Brugada patients are still controversial.

The Brugada syndrome was first described by Pedro and Josep Brugada in 1992 as an inherited cardiac disease causing life‐threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with structurally normal heart and a characteristic ECG showing a pattern of right bundle branch block and ST segment elevation in right precordial leads V1 to V3. 1 Subsequently, more detailed descriptions of three patterns of ECG abnormalities in the right precordial leads were described (defined as types I, II, and III). The syndrome is typically inherited through an autosomal dominant pattern with a significant sporadic incidence. The initial and most common mutations associated with Brugada syndrome have been found in the SCN5A gene encoding the cardiac sodium channel, which invariably acts to mute the transmembrane sodium current (INa) either through a loss of function or an absence of the channel. Despite >100 number of mutations reported, abnormalities in SCN5A are only found in 18–30% of tested patients with presumed Brugada syndrome. This finding supports the notion that a significant genetic heterogeneity underlies the clinical phenotype, and that the SCN5A mutation, although likely the most common, is not the only genetic etiology of this disease. 2 In fitting with this assumption, six additional gene mutations have been described as causative of Brugada syndrome to date. 2

In the present case, mutation‐specific information was not available for diagnosis and risk stratification. Identified clinical and ECG risk factors for sudden cardiac death (SCD) in patients with Brugada syndrome include the presence of symptoms (i.e., syncope) and a spontaneous type‐1 ECG pattern. To guide management in this situation, the second consensus report on Brugada syndrome, published in 2005, 2 recommends EP testing, followed by consideration for ICD implantation in inducible cases. These guidelines formed the basis for the decision to implant an ICD in the present case.

It should be noted, however, that recent studies failed to show that inducibility of ventricular tachyarrhythmias is an independent predictor of subsequent SCD in asymptomatic patients. Recent data from the France, Italy, Netherlands, Germany Brugada syndrome (FINGER) registry, which enrolled 1029 patients with Brugada syndrome who were followed up over a median period of 32 months, show that event rates in asymptomatic Brugada patients are low, and that inducibility during EP testing is a not independently associated with a significant increase in the risk of SCD. 3 These findings are also supported by preliminary data from the Programmed Electrical Stimulation Predictive Value in Brugada syndrome (PRELUDE) registry, which consistently showed that inducibility by EP testing was not a significant predictor for arrhythmic events among 308 patients who were followed over three years. 4

The patient presented was treated with accordance to current guidelines in this case; especially since the presentation and management decisions were undertaken in 2009. It is likely that accumulating data from large registries of Brugada patients will result in revised guideline recommendations that will limit the role of EP testing for risk stratification in this population.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent st segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: A distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20:1391–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, et al. Brugada syndrome: Report of the second consensus conference: Endorsed by the heart rhythm society and the european heart rhythm association. Circulation 2005;111:659–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, et al. Long‐term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada syndrome registry. Circulation 2010;121(5):635–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Napolitano C. Risk stratification and therapy selection in Brugada syndrome – the PRELUDE registry Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Sessions May 2011, San Francisco CA . [Google Scholar]