Abstract

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is an inherited disorder associated with life‐threatening ventricular arrhythmias. An understanding of the relationship between the genotype and phenotype characteristics of LQTS can lead to improved risk stratification and management of this hereditary arrhythmogenic disorder. Risk stratification in LQTS relies on combined assessment of clinical, electrocardiographic, and mutations‐specific factors. Studies have shown that there are genotype‐specific risk factors for arrhythmic events including age, gender, resting heart rate, QT corrected for heart rate, prior syncope, the postpartum period, menopause, mutation location, type of mutation, the biophysical function of the mutation, and response to beta‐blockers. Importantly, genotype‐specific therapeutic options have been suggested. Lifestyle changes are recommended according to the prevalent trigger for cardiac events. Beta‐blockers confer greater benefit among patients with LQT1 with the greatest benefit among those with cytoplasmic loops mutations; specific beta‐blocker agents may provide greater protection than other agents in specific LQTS genotypes. Potassium supplementation and sex hormone–based therapy may protect patients with LQT2. Sodium channel blockers such as mexiletine, flecainide, and ranolazine could be treatment options in LQT3.

Keywords: long QT syndrome, cardiac arrest/sudden death

GENETICS AND MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF THE MAIN LQTS GENOTYPES

The hereditary long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a genetic channelopathy with variable penetrance and expressivity. Clinically, LQTS is recognized by abnormal QT interval prolongation on the ECG and is associated with increased risk of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, syncope, and sudden cardiac death (SCD). It has an estimated prevalence of 1:2000 to 1:5000.1, 2 To date, more than 600 mutations have been identified in 13 LQTS genes. The LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3 genotypes comprise more than 95% of the patients with genotype‐positive LQTS and approximately 75% of all patients with LQTS. The most common pattern of inheritance of LQTS is autosomal dominant (Romano‐Ward syndrome), but there is also an autosomal recessive form of inheritance. The presence of two mutations in either the KCNQ1 (LQT1) or KCNE1 (LQT5) gene results in the Jervell and Lange‐Nielsen syndrome, a severe form of LQTS with sensory hearing loss. Mutations in LQTS genes affect different ion channels and produce gain or loss of function that determine phenotypic manifestations of the disease. Most commonly, QT prolongation arises either from a decrease in repolarizing potassium current during phase 3 of the action potential (“loss of function”), or a prolonged depolarization due to late inward entry into the myocyte sodium or calcium current (“gain of function”).

These channels are composed of primary alfa‐ and secondary beta‐subunits, which oligomerize into a polymer that inserts into the cell membrane to form a functional ion channel. The alpha subunit of the voltage‐gated potassium channels includes six membrane‐spanning segments, S1 though S6, joined together by alternating intra‐ and extracellular loops, a pore region located between S5 and S6 segments with the amino and carboxyl termini, located inside the cytoplasm. The cardiac sodium channel SCN5A and L‐type calcium channel CACNA1C, consist of four homologous domains, and each domain contains six transmembrane domains, similar to four linked potassium channel modules.

LQTS type 1 (LQT1) is caused by a mutation in the KCNQ1 gene leading to dysfunction of the KvLQT1 potassium channel and reduction in the slowly activating repolarizing cardiac potassium current (I Ks). The mutations associated with the KCNQ1 genes act mainly through a dominant‐negative mechanism when the normal and mutant subunits create the defective channel protein resulting in dysfunctional channel with more than 50% reduction in the channel current. The other common biophysical mechanism leading to decreased potassium current is haploinsufficiency in which potassium channel mutant subunits are incapable in co‐assembling with the normal subunits to form a tetramer channel. Therefore, only subunits encoded by a normal allele form a functional channel resulting in 50% or less reduction in channel function.

In LQTS type 2 (LQT2), a mutation in the KCNH2 gene leads to dysfunction of the hERG potassium channel and reduction in the rapidly activating repolarizing cardiac potassium current (I Kr).

LQTS type 3 (LQT3) is caused by a mutation in the SCN5A gene leading to dysfunction of the Nav1.5 protein, increasing the cardiac sodium current influx (I Na).

Reduced repolarizing potassium current or increase in the late sodium current, leads to prolongation of the ventricular action potential and early afterdepolarizations, which are the potential triggers for ventricular tachyarrhythmias. LQTS types 4–13 are rare, representing less than 5% of patients with genotype‐positive LQTS.

GENOTYPE–PHENOTYPE CORRELATIONS IN LQTS

LQTS genes affect different ion‐current mechanisms; thus, the type of ion channel mutation can affect phenotypic expression. Distinct genotype–phenotype correlations have been recognized in LQTS. ST‐T wave patterns on the electrocardiogram and the triggers for cardiac events vary between the three genotypes. In addition, gene‐specific differences in risk for cardiac events have also been described, with the genotype‐specific risk factors including the type of trigger for cardiac event, age, gender, resting heart rate, mutation location, and response to beta‐blockers.

The ST‐T wave repolarization pattern on the EKG is different for each genotype. LQT1 patients typically have a broad‐based T wave pattern; in LQT2 the ECG demonstrates a low amplitude bifid T wave. In LQT3, T wave is usually late onset, and peaked, bifid, or morphologically asymmetrical.

It has been shown that life‐threatening arrhythmias in LQTS patients occur under specific circumstances. In a study of 670 symptomatic LQTS patients with one of the three main LQTS genotypes,3 LQT1 patients were shown to experience 62% of cardiac events (including syncope, aborted cardiac arrest [ACA], and SCD) during exercise and only 3% during sleep/rest. By contrast, LQT3 patients experienced 13% of the events during exercise and 39% occurred at sleep/rest. LQT2 patients had an intermediate pattern, with only 13% occurring during exercise and most of the remainder (43%) occurring with emotional stress (i.e., fear, anger, startle, or sudden noise during sleep/rest). Similar trigger distribution pattern was found for the lethal cardiac events (ACA and SCD). This study and others4, 5, 6, 7 have shown that patients with the LQT1 genotype are at a higher risk for arrhythmic events triggered by sympathetic activation induced by exercise. Among the different types of exercise, swimming was shown to be a specific trigger for LQT1 patients.4, 5 In contrast, patients with the LQT2 genotype experience cardiac events associated with sudden loud noise, whereas patients with the LQT3 genotype experience events during sleep or at rest without emotional arousal.

RISK STRATIFICATION FOR CARDIAC EVENTS IN LQTS PATIENTS

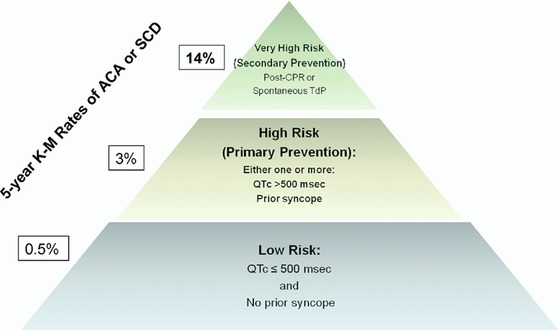

Risk stratification relies on a combined assessment of clinical information, EKG and mutation‐specific factors. Based on existing data among nongenotyped patients, LQTS patients may be classified into three main risk categories (Fig. 1): very high risk, high risk, and low risk (5‐year Kaplan‐Meier cumulative estimate rate of ACA/SCD is 14%, 3%, and 0.5%, respectively).8 The patients in the very high‐risk group are those with a history of ACA and/or spontaneous torsades de pointes; these patients require an ICD implantation for secondary prevention of SCD. The high‐risk group includes subjects with history of prior syncope or QTc of over 500 ms, and the low risk group includes those with QTc duration of 500 ms, or less and without prior syncopal event.

Figure 1.

Suggested risk stratification for life‐threatening cardiac events in patients with the long QT syndrome. ACA = aborted cardiac arrest; K‐M = Kaplan Meier; SCD = sudden cardiac death; TdP = Torsades de pointes. The figure is taken with permission from Kim et al.8

GENOTYPE‐SPECIFIC RISK STRATIFICATION

Multiple studies have shown that there are genotype‐specific factors affecting the phenotypic expression in patients with LQTS; those risk factors include age, gender, the postpartum time period, menopause, resting heart rate, prior syncope, mutation location, type of mutation (missense/nonmissense), the biophysical function of the mutation, and response to beta‐blockers. In addition, cardiac events triggered by exercise, arousal, or rest/sleep are associated with distinctive clinical and genetic risk factors.

RISK STRATIFICATION IN LQTS TYPE 1

Recent data indicate that the location, type, and biophysical function of the KCNQ1 mutation are important independent risk factors influencing the clinical course of patients with LQT1. Moss et al.9 have demonstrated among 600 patients with 77 different KCNQ1 mutations, that patients with mutations in the transmembrane region (including the cytoplasmic loops [C‐loops] domains) compared to mutations in the C‐terminus of the KCNQ1 channel had a twofold (P < 0.001) increased risk for syncope, ACA, or SCD. Similarly, patients with dominant‐negative ion‐current effects (>50% reduction in channel current) had a 2.2‐fold increase (P < 0.001) in the risk of cardiac events compared to those who had mutations with haploinsufficiency effect (≤50% reduction in channel current). Furthermore, this study has shown that patients with missense mutations had a significantly higher risk of cardiac events compared to those with nonmissense mutations. Most recently, we have analyzed data on 860 patients with a KCNQ1 mutation from the international LQTS registry.10 Patients were categorized into carriers of missense mutations located in the C‐loops (S2–S3 and S4–S5 domains), membrane spanning domain, C/N‐terminus, and nonmissense mutations. There were 27 ACA and 78 SCD events from birth through age 40 years. The presence of C‐loop mutations was associated with the longest QTc on the ECG and with highest risk for ACA or SCD (hazard ratio [HR] 2.75, P = 0.009 compared with nonmissense mutations). It is known that C‐loops play an important role in the sympathetic regulation of the KCNQ1 channel.11 Based on results from cellular expression studies,10 we have suggested that a combination of decrease in basal function and altered adrenergic regulation of the I Ks channel underlies the increased cardiac risk in this subgroup of patients.

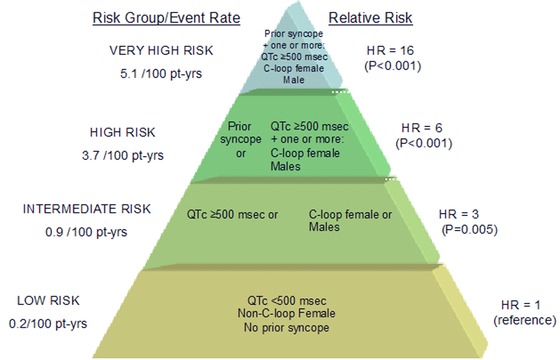

There are accumulating data showing that the risk for cardiac events in LQT1 is affected by sex and age. Zareba et al.12 have shown in 243 subjects with LQT1 that during childhood (age group: 0–15 years), there was a 1.7‐fold (P = 0.005) increased risk for cardiac events (syncope, ACA, or SCD) among males compared to females, whereas during adulthood, LQT1 females had a 3.3‐fold (P = 0.007) higher risk for cardiac events compared with males. We have further assessed the sex‐specific risk factors for life‐threatening cardiac events (ACA/SCD) in a large population of 1051 genetically confirmed patients with LQT1 from the US portion of the International LQTS Registry.13 We have found that during childhood (age group: 0–13 years) males had >twofold (P = 0.003) increased risk for ACA/SCD than did females, whereas after the onset of adolescence the risk for ACA/SCD was similar between men and women (HR = 0.89, P = 0.64). Importantly, mutation location showed a sex‐specific association with the risk for ACA or SCD. The presence of C‐loop domains mutations was associated with a 2.7‐fold (P < 0.001) increased risk for ACA/SCD among women, whereas the risk for ACA/SCD among men with LQT1 was high, predominantly during the childhood period, regardless of mutation location/type. Additional risk factors for ACA or SCD among both men and women included a prolonged QTc (>500 ms) and the occurrence of time‐dependent syncope.13 Time‐dependent syncope was associated with a more pronounced risk‐increase among men than among women (HR 4.73, [P < .001] and 2.43 [P = 0.02], respectively), whereas a prolonged corrected QT interval (≥500 ms) was associated with a higher risk among women than among men. The proposed risk stratification scheme for ACA or SCD in LQT1 based on these findings is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proposed risk stratification for aborted cardiac arrest or sudden cardiac death in LQT1. Pt‐yrs = patient years; HR = hazard ratio. The figure is taken with permission from Costa et al.13

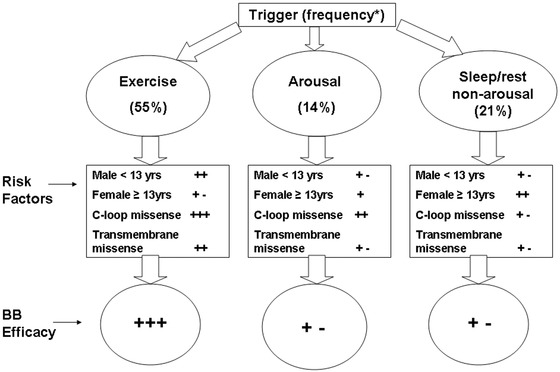

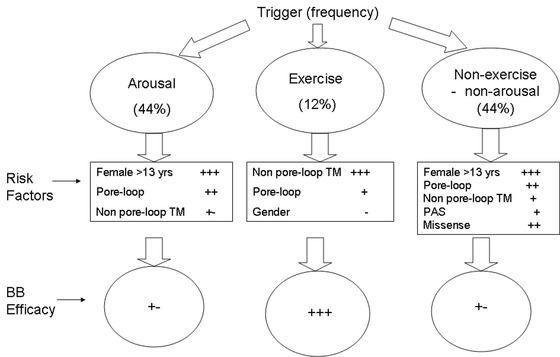

In LQT1, the majority of events are triggered by exercise activity and a lower proportion of events are associated with acute arousal or sleep/rest. In a recent study carried out among 721 genetically confirmed patients with LQT1 from the US portion of the International LQTS Registry,6 we have analyzed the independent contribution of clinical and genetic risk factors to the first occurrence of trigger‐specific cardiac events, categorized as exercise induced, arousal, and nonarousal/nonexercise. This study showed that age and gender have a distinct association with exercise‐, arousal‐, and sleep/rest‐triggered events in patients with LQT1. During childhood (age < 13 years) males had a 2.8‐fold (P < 0.001) increase in the risk for exercise‐triggered events, whereas females > 13 years showed a 3.5‐fold (P = 0.002) increase in the risk for sleep/rest nonarousal events Mutations located in the C‐loops portion of the KCNQ1 channel were associated with an increased risk for cardiac events triggered by both exercise‐ and arousal‐triggered events (i.e., sympathetic stimulation, HR = 6.19 [P < 0.001] and HR = 4.99 [P < 0.001], respectively), but were not related to sleep/rest nonarousal events (HR = 0.72, P = 0.46). Figure 3 summarizes the trigger‐specific risk factors for cardiac events in LQT1.

Figure 3.

Trigger‐specific risk factors and response to therapy in LQT1. BB = beta‐blockers; C‐loops = cytoplasmic loops. The figure is taken with permission from Ref. 6.

Finally, it has been shown that faster resting heart rates are associated with increased risk for cardiac events in LQT1 patients, and that resting heart rate provides incremental prognostic information to mere assessment of QTc in LQT1 but not in LQT2 patients.14, 15, 16 Thus, we have suggested that risk stratification for life‐threatening cardiac events in LQTS patients may be improved by incorporating a genotype‐specific correction of the QT interval for heart rate with a greater degree of QT correction for heart rate in LQT1 (improved QTc = QT/RR0.8) than in LQT2 patients (improved QTc = QT/RR0.2).16

RISK STRATIFICATION IN LQTS TYPE 2

Similar to LQT1, the type and location of KCNH2 mutations were shown to be linked to the risk of cardiac events in patients with LQT2. In a study of 858 subjects with 162 different KCNH2 mutations, Shimizu et al.17 have reported that patients with missense mutations located in the transmembrane pore region (S5‐loop‐S6 region) are associated with the greatest risk for cardiac events. Furthermore, mutations located in the alfa‐helical domain of the KCNH2 channel were associated with a significantly higher risk compared to mutations in either the beta‐sheet domains or other uncategorized locations.

With regard to the effect of gender and age on the phenotypic expression in LQT2 patients, Zareba et al.12 assessed the risk of cardiac events in 209 carriers of KCNH2 mutations and found that females >15 years old had a 3.7‐fold (P = 0.01) increased risk for cardiac events as compared to males >15 years old, but there was no significant difference between female and male carriers ≤15 years old (HR = 0.73, P = 0.3).

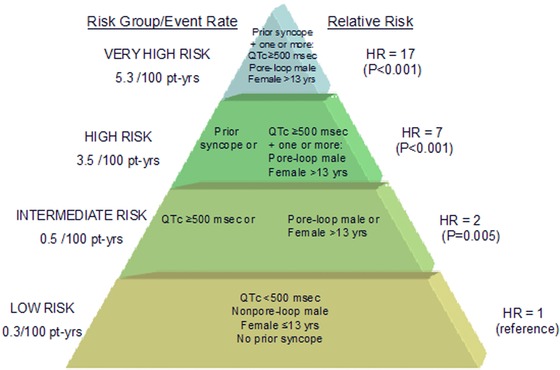

Migdalovich et al.18 have investigated the relationship between mutation location in the KCNH2 channel and gender‐specific risk for life‐threatening cardiac events (ACA/SCD). This study among 1166 patients with LQT2 showed that the risk for life‐threatening cardiac events from birth through age 40 years was significantly higher among women than men, with a cumulative probability of life‐threatening cardiac events of 26% and 14% among women and men, respectively (P < 0.001). The increased risk for ACA/SCD among LQT2 females was pronounced after the age of 13 years. The risk for life‐threatening cardiac events was not significantly different between women with and without pore‐loop mutations (HR 1.20, P = 0.3). In contrast, men with pore‐loop mutations displayed a significant > twofold higher risk of a first ACA/SCD as compared to those with nonpore‐loop mutations (HR = 2.18, P = 0.01). Figure 4 shows a proposed risk stratification scheme for ACA or SCD in LQT2 patients.

Figure 4.

Proposed risk stratification scheme for aborted cardiac arrest or sudden cardiac death in LQT2 patients. Pt‐yrs = patient years; HR = hazard ratio. The figure is taken with permission from Migdalovich et al.18

As mentioned earlier, most of cardiac event stimuli in LQT2 patients are sudden arousal triggers, whereas a lower proportion of events are associated with exercise activity. We have recently carried out a study among 634 genetically confirmed LQT2 patients 7 investigating the clinical and genetic factors associated with trigger‐specific risk for cardiac events. Females >13 years as compared to males >13 years had a ninefold (P < 0.001) increased risk for arousal triggered cardiac events and patients with pore‐loop mutations had a >twofold increased risk for this endpoint (P = 0.009). In contrast, nonpore‐loop transmembrane mutations were associated with a 6.8‐fold (P < 0.001) increased risk for exercise‐triggered events, whereas gender was not a significant risk factor for this endpoint. Risk factors for nonexercise/nonarousal events included female gender, mutation location and type, and prolonged QTc (>500 ms).

Thus, in both LQT1 and LQT2, risk factors for cardiac events showed a trigger‐specific association with arrhythmic cardiac events. Figure 5 summarizes the trigger‐specific risk factors for cardiac events in LQT2.

Figure 5.

Trigger‐specific risk factors and response to therapy in LQT2 patients. BB = beta‐blockers. The figure is taken with permission from Kim et al.7

There is accumulating data suggesting that sex hormones may affect arrhythmic risk in LQTs patients, and that this increased risk in cardiac events is more pronounced in LQT2 women. LQT2 women experience a significant increase in the risk of cardiac events after the onset of adolescence.12, 18 Female sex is associated with a longer baseline QTc, and is an independent risk factor for development of torsades de pointes in acquired LQTS (affecting the I Kr current).19, 20

Seth at al.21 have shown among 391 women with LQTS who gave birth that the nine‐month postpartum time is associated with a 2.7‐fold increased risk for a cardiac event and a 4.1‐fold increased risk for a life‐threatening event when compared to the preconception time period. Women with the LQT2 genotype were at a considerably higher risk for cardiac events during the postpartum period than those with LQT1 or LQT3 genotypes.

Buber et al.22 have shown among 151 LQT1 women and 131 LQT2 women that the perimenopausal period was associated with a pronounced increase in the risk for recurrent episodes of syncope in LQT2 women. During the 5‐year time period before menopause, LQT2 women had a 3.4‐fold increased risk for syncope (P = 0.005). Furthermore, during the 5‐year time period after onset of menopause, LQT2 women had a 8.1‐fold increased risk for syncope (P < 0.001). By contrast, the onset of menopause was associated with a reduction in the risk for recurrent syncope in LQT1 women (HR = 0.19, P = 0.05, P = 0.02 for genotype‐by‐menopause interaction).

RISK STRATIFICATION IN LQTS TYPE 3

As described above, a gain of function mutation in the cardiac sodium channel SCN5A leads to LQT3. The SCN5A channels open quickly in response to depolarization but within a few milliseconds the channels undergo fast inactivation. The mutations leading to LQT3 produce gain of function defects by disrupting this inactivation causing late persistent sodium currents, window sodium currents, or both.23

Preliminary findings from data of LQT3 patients enrolled in the US portion of the LQTS Registry show that mutations involving two functional defects (i.e., mutations leading to both late sodium currents and window sodium currents) had a 2.5‐fold (P = 0.001) increased risk for ACA/SCD as compared with mutations involving only one functional defect. In addition, no significant difference in the risk of cardiac events was observed among LQT3 patients with mutations in transmembrane versus C‐terminus segments of the SCN5A channel.

Liu et al.24 investigated the clinical course of patients with two relatively common LQT3 mutations. The study population involved 50 patients with the ΔKPQ mutation and 35 patients with the missense D1790G mutation of the SCN5A gene. Patients with the ΔKPQ mutation had a 2.4‐fold (P < 0.001) higher risk for cardiac events from birth through age 40 years compared to patients with the D1790G mutation, demonstrating the importance of knowing the specific mutation in risk stratification of LQT3 patients.

Zareba et al.12 assessed the risk of cardiac events in 81 carriers of SCN5A mutations and found no trend toward age and gender dependency of the risk for cardiac events in patients with LQT3. The lethality of cardiac events in males and females with LQT3 was similar, but was significantly higher than in LQT1 and LQT2 patients.

GENOTYPE‐SPECIFIC MANAGEMENT

In general, management of LQTS includes life style modifications (avoiding the known triggers for LQTS associated cardiac events), medical therapy with beta‐blockers, device, and surgical therapies. According to current guidelines,25 there is a class I indication for beta‐blockers treatment among patients with a clinical diagnosis of LQTS (i.e., in the presence of prolonged QT interval) and there is a class IIa indication for beta‐blockers treatment among carriers of LQTS mutations. Device therapy with an implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator (ICD) is reserved for LQTS patients with history of ACA (class I indication) or for LQTS patients who experienced syncope or ventricular tachycardia (VT) despite beta‐blocker therapy (class IIa indication).26 Surgical approach with left cervicothoracic sympathetic denervation (LCSD) should be considered in patients with recurrent syncope despite beta‐blocker therapy and in patients who experience VT storm with an ICD.27, 28 Permanent pacemaker implantation might be considered in patients with LQTS and bradycardia.

Known that patients with certain genotype are more likely to experience their events under well‐defined conditions, this can provide guidance to a prevention approach. Patients with LQT1 should avoid or limit their physical activity since the majority of them experience their events during exercise. Swimming and competitive sports should be restricted. Avoidance of unexpected auditory stimuli such as sudden loud noise, alarm clocks, and phone ringing should be advised in all patients with LQT2, especially in postadolescent women with mutations in the pore segment of the hERG channel. Since patients with the LQT3 genotype experience events during sleep or at rest without emotional arousal, they should consider having an intercom system in their bedroom and the younger patients should not sleep alone.

Beta‐blocker therapy is considered a mainstay therapy in all high and intermediate risk patients with LQTS. It was shown that high‐risk patients including LQT1 men and LQT2 women have a significant risk‐reduction with beta‐blockers (67%, P = 0.02 and 71%, P < 0.001, respectively).29 The lower risk patient should also be treated with beta‐blocker therapy unless contraindicated because the cumulative probability of adverse events may still be high. Unfortunately, the protective effect of beta‐blockers is not uniform in LQTS patients, and they are thought to be more beneficial in patients with LQT1 compared with LQT2 and LQT3.30, 31 Their effect is also linked to specific mutations. Thus, it was demonstrated that beta‐blocker therapy had been associated with a significant 88% reduction in the risk of life‐threatening cardiac events among LQT1 carriers of the C‐loop missense mutations (P = 0.02) compared with other patients with non–C‐loop missense mutations (HR 0.82, P = 0.68).10 In addition, it has been suggested both in LQT1 and LQT2 patients that there exists a trigger‐specific response to beta‐blockers. Beta‐blocker therapy was associated with a 78% (P < 0.001) reduction and with a 71% (P = 0.01) reduction in the risk for exercise‐triggered cardiac events in LQT1 and LQT2 patients, respectively, but did not have a significant effect on events associated with arousal or sleep/rest in both LQT1 and LQT2 patients.6, 7 Preliminary data from the International LQT3 group has shown that beta‐blockers are also effective in preventing cardiac events among LQT3 patients.

The efficacy of different beta‐blocker agents in LQTS is not the same. In a cohort of 382 with LQT1 or LQT2, Chockalingam et al.32 have found that QTc shortening was significantly greater with propranolol than with metoprolol or nadolol. Also, there was a greater risk of cardiac events for symptomatic patients initiated on metoprolol compared to users of propranolol or nadolol (odds ratio 3.95, P = 0.025). We have recently carried out a study among 971 LQT1 and LQT2 patients from the International LQTS Registry investigating the efficacy of beta‐blockers in reducing the risk for cardiac events. Among LQT1 patients, atenolol showed the greatest efficacy out of the different beta‐blocker agents in reducing cardiac events (HR 0.23, P = 0.008), whereas metoprolol exhibited the lowest efficacy (HR 0.65, P = 0.7). Among LQT2 patients, nadolol was the most effective agent (HR 0.13, P = 0.01), whereas metoprolol was not associated with a significant reduction in cardiac events (HR 0.64, P = 0.7).

Treatments such as potassium supplementation and spironolactone were proposed for patients with LQT2. Since the conductance of the hERG channel is directly related to extracellular K+, it was suggested that potassium administration will increase serum potassium level and may partially correct the repolarization abnormalities. Two small studies have shown that potassium supplements and spironolactone are associated with a significant shortening of the QTc and partially correct the repolarization abnormalities.33, 34 Unfortunately, none have demonstrated that potassium supplements can decrease the risk of cardiac events. One unpublished randomized trial of potassium supplementation + spironolactone aimed to evaluate the possible risk reduction in cardiac events stopped prematurely due to safety concerns including higher rates of hyperkalemia.

Progesterone was shown to shorten QTc and to provide protection against arrhythmias through modulation of I Ks and L‐type calcium currents.35 By contrast, estrogen was shown to decrease I Kr channel expression and prolong QTc.36

Recently, Odening et al.37 investigated the effects of sex hormones on arrhythmia risk in a transgenic LQT2 rabbit model and showed that estradiol promotes SCD, whereas progesterone is protective in LQT2 rabbits. This data may suggest an important role for sex hormones (particularly progesterone) in the treatment of LQT2 patients.

The management of LQT3 is also challenging. Sodium channel blockers such as mexiletine and flecainide have been investigated as a potential treatment option for patients with LQT3 in the last two decades.38, 39, 40 Schwartz et al.41 have demonstrated that mexiletine significantly shortens the QT interval in LQT3 but not in LQT2 patients. Wang et al.38 demonstrated that mexiletine selectively target the mutant channels and preferentially suppress the late sodium current compared with the peak sodium current.

Ruan et al.39 have shown that the response to mexiletine is mutation specific and suggested that in vitro testing may help to predict the response to mexiletine in LQT3. Similar to mexiletine, flecainide was also shown to shorten the QTc in LQT3 patients.42 Another antiarrhythmic medication, ranolazine, may also have beneficial effects in LQT3 patients. Moss et al. demonstrated that ranolazine shortened a prolonged QTc interval and improved diastolic relaxation in five patients with the LQT3 ΔKPQ mutation.43

The rationale behind the LCSD surgical procedure is that it causes reduction in the adrenergic surge in the heart without affecting heart rate, which makes it an attractive option also for patients with LQT3 who are at a higher risk at longer cycle length. In a study of 147 high‐risk patients with LQTS,28 the mean annual number of cardiac events per patient has dropped by 91% (P < 0.001), and the post‐LCSD count of shocks in patients with pre‐LCSD multiple ICD therapies has decreased by 95% (P = 0.02) after LSCD. In a secondary analysis of 51 genotyped patients, LCSD appeared more effective in LQT1 and LQT3 patients. The authors suggested that LCSD should be considered in patients with recurrent syncope despite beta‐blockade and in patients who experience arrhythmia storms with an ICD.

SUMMARY

Genotype–phenotype correlation in the LQTS has been the most active line of research among the genetic diseases associated with life‐threatening ventricular arrhythmias. The discovery that genes responsible for LQTS encode different ion channels involved in the control of the cardiomyocyte repolarization has led to important advancements in current knowledge regarding the relationship between basic causal mechanisms and clinical aspects of LQTS. It has been shown that life‐threatening arrhythmias in LQTS patients occur under specific circumstances and in a gene‐specific manner. The interplay between the genetic defect, QT duration, age, and gender can provide an algorithm for risk stratification in LQTS. In this review, we have further outlined genotype‐specific algorithms for risk stratification, utilizing different variables for LQT1 and LQT2. Most importantly, an understanding of the genotype–phenotype relationship can lead to improved management of LQTS. For the past two decades, there were some advancements in developing new treatments to the most prevalent genetic variants of LQTS; however, development of genotype‐specific management strategies that take into account genotype/mutation‐specific response to therapy is very challenging requiring collaboration between clinical and basic scientists and highlighting the need for randomized controlled clinical trials in this field.

REFERENCES

- 1. Quaglini S, Rognoni C, Spazzolini C, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of neonatal ECG screening for the long QT syndrome. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1824–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ. Low penetrance in the long‐QT syndrome: Clinical impact. Circulation 1999;99:529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, et al. Genotype‐phenotype correlation in the long‐QT syndrome: Gene‐specific triggers for life‐threatening arrhythmias. Circulation 2001;103:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ackerman MJ, Tester DJ, Porter CJ. Swimming, a gene‐specific arrhythmogenic trigger for inherited long QT syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 1999;74:1088–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moss AJ, Robinson JL, Gessman L, et al. Comparison of clinical and genetic variables of cardiac events associated with loud noise versus swimming among subjects with the long QT syndrome. Am J Cardiol 1999;84:876–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goldenberg I, Thottathil P, Lopes CM, et al. Trigger‐specific ion‐channel mechanisms, risk factors, and response to therapy in type 1 long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim JA, Lopes CM, Moss AJ, et al. Trigger‐specific risk factors and response to therapy in long QT syndrome type 2. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:1797–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goldenberg I, Moss AJ. Long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:2291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moss AJ, Shimizu W, Wilde AA, et al. Clinical aspects of type‐1 long‐QT syndrome by location, coding type, and biophysical function of mutations involving the KCNQ1 gene. Circulation 2007;115:2481–2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barsheshet A, Goldenberg I, J O‐Uchi, et al. Mutations in cytoplasmic loops of the KCNQ1 channel and the risk of life‐threatening events: Implications for mutation‐specific response to beta‐blocker therapy in type 1 long‐QT syndrome. Circulation 2012;125:1988–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matavel A, Medei E, Lopes CM. PKA and PKC partially rescue long QT type 1 phenotype by restoring channel‐PIP(2) interactions. Channels (Austin) 2010;4(1): 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zareba W, Moss AJ, Locati EH, et al. Modulating effects of age and gender on the clinical course of long QT syndrome by genotype. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Costa J, Lopes CM, Barsheshet A, et al. Combined assessment of sex‐ and mutation‐specific information for risk stratification in type 1 long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:892–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schwartz PJ, Vanoli E, Crotti L, et al. Neural control of heart rate is an arrhythmia risk modifier in long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:920–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brink PA, Crotti L, Corfield V, et al. Phenotypic variability and unusual clinical severity of congenital long‐QT syndrome in a founder population. Circulation 2005;112:2602–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barsheshet A, Peterson DR, Moss AJ, et al. Genotype‐specific QT correction for heart rate and the risk of life‐threatening cardiac events in adolescents with congenital long‐QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2011;8:1207–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shimizu W, Moss AJ, Wilde AA, et al. Genotype‐phenotype aspects of type 2 long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:2052–2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Migdalovich D, Moss AJ, Lopes CM, et al. Mutation and gender‐specific risk in type 2 long QT syndrome: Implications for risk stratification for life‐threatening cardiac events in patients with long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2011;8:1537–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lehmann MH, Hardy S, Archibald D, et al. Sex difference in risk of torsade de pointes with d,l‐sotalol. Circulation 1996;94:2535–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. James AF, Choisy SC, Hancox JC. Recent advances in understanding sex differences in cardiac repolarization. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2007;94:265–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seth R, Moss AJ, McNitt S, et al. Long QT syndrome and pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1092–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buber J, Mathew J, Moss AJ, et al. Risk of recurrent cardiac events after onset of menopause in women with congenital long‐QT syndrome types 1 and 2. Circulation 2011;123:2784–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dumaine R, Wang Q, Keating MT, et al. Multiple mechanisms of Na +channel–linked long‐QT syndrome. Circ Res 1996;78:916–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu JF, Moss AJ, Jons C, et al. Mutation‐specific risk in two genetic forms of type 3 long QT syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2010;105:210–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death). J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e247–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Epstein AE, Dimarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for Device‐Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: Executive summary. Heart rhythm 2008;5:934–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schneider HE, Steinmetz M, Krause U, et al. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation for the management of life‐threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias in young patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and long QT syndrome. Clin Res Cardiol 2013;102:33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Cerrone M, et al. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation in the management of high‐risk patients affected by the long‐QT syndrome. Circulation 2004;109:1826–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goldenberg I, Bradley J, Moss A, et al. Beta‐blocker efficacy in high‐risk patients with the congenital long‐QT syndrome types 1 and 2: Implications for patient management. J Cardiovas Electrophysiol 2010;21:893–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, et al. Association of long QT syndrome loci and cardiac events among patients treated with beta‐blockers. JAMA 2004;292:1341–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vincent GM, Schwartz PJ, Denjoy I, et al. High efficacy of beta‐blockers in long‐QT syndrome type 1: Contribution of noncompliance and QT‐prolonging drugs to the occurrence of beta‐blocker treatment “failures”. Circulation 2009;119:215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chockalingam P, Crotti L, Girardengo G, et al. Not all beta‐blockers are equal in the management of long QT syndrome types 1 and 2: Higher recurrence of events under metoprolol. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:2092–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Compton SJ, Lux RL, Ramsey MR, et al. Genetically defined therapy of inherited long‐QT syndrome. Correction of abnormal repolarization by potassium. Circulation 1996;94:1018–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Etheridge SP, Compton SJ, Tristani‐Firouzi M, et al. A new oral therapy for long QT syndrome: Long‐term oral potassium improves repolarization in patients with HERG mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1777–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nakamura H, Kurokawa J, Bai CX, et al. Progesterone regulates cardiac repolarization through a nongenomic pathway: An in vitro patch‐clamp and computational modeling study. Circulation 2007;116:2913–2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kurokawa J, Tamagawa M, Harada N, et al. Acute effects of oestrogen on the guinea pig and human IKr channels and drug‐induced prolongation of cardiac repolarization. J Physiol 2008;586:2961–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Odening KE, Choi BR, Liu GX, et al. Estradiol promotes sudden cardiac death in transgenic long QT type 2 rabbits while progesterone is protective. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:823–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang HW, Zheng YQ, Yang ZF, et al. Effect of mexiletine on long QT syndrome model. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2003;24:316–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ruan Y, Liu N, Bloise R, et al. Gating properties of SCN5A mutations and the response to mexiletine in long‐QT syndrome type 3 patients. Circulation 2007;116:1137–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nagatomo T, January CT, Makielski JC. Preferential block of late sodium current in the LQT3 DeltaKPQ mutant by the class I(C) antiarrhythmic flecainide. Mol Pharmacol 2000;57:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Locati EH, et al. Long QT syndrome patients with mutations of the SCN5A and HERG genes have differential responses to Na+ channel blockade and to increases in heart rate. Implications for gene‐specific therapy. Circulation 1995;92:3381–3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Benhorin J, Taub R, Goldmit M, et al. Effects of flecainide in patients with new SCN5A mutation: Mutation‐specific therapy for long‐QT syndrome? Circulation 2000;101:1698–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moss AJ, Zareba W, Schwarz KQ, et al. Ranolazine shortens repolarization in patients with sustained inward sodium current due to type‐3 long‐QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2008;19:1289–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]