Abstract

Abstract

Absolute quantification of radiotracer distribution using SPECT/CT imaging is of great importance for dosimetry aimed at personalized radionuclide precision treatment. However, its accuracy depends on many factors. Using phantom measurements, this multi-vendor and multi-center study evaluates the quantitative accuracy and inter-system variability of various SPECT/CT systems as well as the effect of patient size, processing software and reconstruction algorithms on recovery coefficients (RC).

Methods

Five SPECT/CT systems were included: Discovery™ NM/CT 670 Pro (GE Healthcare), Precedence™ 6 (Philips Healthcare), Symbia Intevo™, and Symbia™ T16 (twice) (Siemens Healthineers). Three phantoms were used based on the NEMA IEC body phantom without lung insert simulating body mass indexes (BMI) of 25, 28, and 47 kg/m2. Six spheres (0.5–26.5 mL) and background were filled with 0.1 and 0.01 MBq/mL 99mTc-pertechnetate, respectively. Volumes of interest (VOI) of spheres were obtained by a region growing technique using a 50% threshold of the maximum voxel value corrected for background activity. RC, defined as imaged activity concentration divided by actual activity concentration, were determined for maximum (RCmax) and mean voxel value (RCmean) in the VOI for each sphere diameter. Inter-system variability was expressed as median absolute deviation (MAD) of RC. Acquisition settings were standardized. Images were reconstructed using vendor-specific 3D iterative reconstruction algorithms with institute-specific settings used in clinical practice and processed using a standardized, in-house developed processing tool based on the SimpleITK framework. Additionally, all data were reconstructed with a vendor-neutral reconstruction algorithm (Hybrid Recon™; Hermes Medical Solutions).

Results

RC decreased with decreasing sphere diameter for each system. Inter-system variability (MAD) was 16 and 17% for RCmean and RCmax, respectively. Standardized reconstruction decreased this variability to 4 and 5%. High BMI hampers quantification of small lesions (< 10 ml).

Conclusion

Absolute SPECT quantification in a multi-center and multi-vendor setting is feasible, especially when reconstruction protocols are standardized, paving the way for a standard for absolute quantitative SPECT.

Keywords: SPECT/CT, absolute quantification, recovery coefficient, performance evaluation

Introduction

Accurate absolute quantification of radiotracer distribution is essential for dosimetry aimed at personalized radionuclide therapy and may improve prediction of therapy response, prevention of toxicity effects, and treatment follow-up [1, 2]. Both positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) hold the promise for absolute radioactivity quantification. However, for SPECT, quantification is considered less straightforward [3, 4] since its accuracy depends on a variety of factors, including the necessary use of a collimator, the varying detector trajectory, and the need for more complicated scatter correction and attenuation correction than in PET [4]. Furthermore, quantification is influenced by both the reconstruction algorithm and settings. Recent developments in corrections for photon attenuation and scatter, collimator modeling and 3D reconstruction, e.g., by including resolution recovery and noise regulation, have improved reconstruction techniques, thereby enabling absolute SPECT quantification [5]. The addition of an integrated computed tomography (CT) system not only provides an anatomical reference but enables accurate attenuation and scatter correction as well, improving quantification [6]. Nowadays, combined SPECT/CT systems have become standard clinical practice.

Standardization of protocols in such a way that quantitative results can be reliably compared between systems requires more insight in their quantitative accuracy and performance. For PET/CT, differences in absolute quantification of various systems have been extensively characterized through the European Association of Nuclear Medicine initiative of EANM Research Ltd. (EARL). As part of this initiative, quantification of the most widely used PET radiotracer, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG), has been standardized in a multi-center setting through an accreditation program [7, 8].

Until date, no similar efforts for SPECT/CT have been carried out, which hampers multi-center research trials involving absolute SPECT quantification, especially those aimed towards dosimetry. The requirements on quantification for dosimetry are described in MIRD Pamphlet No. 23 [9]. With the advent of, for example, 177Lu-PSMA therapy [10–13], it is expected that dosimetry will play a pivotal role for reliable determination of dose response relationships. But also our understanding of biomarker studies and already well-established radionuclide therapies in thyroid cancer [14, 15] or neuroendocrine tumors [16–20] may profit from optimized quantitative SPECT imaging for sophisticated dosimetry. In addition, quantitative measurements are increasingly used in diagnosis or disease monitoring [21]. Several studies investigated the quantitative performance of SPECT for a variety of radionuclides, including technetium-99m (99mTc) [22, 23], indium-111 (111In) [24–26], iodine-131 (131I) [27], lutetium-177 (177Lu) [28], yttrium-90 (90Y) [29], or a combination of these [30, 31]. However, comparing these results of absolute quantification may be difficult as they were obtained on different SPECT/CT systems. Seret et al. [32] compared four SPECT/CT systems for their quantitative capabilities and found that for objects which dimensions exceeded the SPECT spatial resolution several times, quantification was possible within a 10% error. For smaller structures, larger errors were observed necessitating partial volume effect correction. Furthermore, reconstruction artifacts degraded the accuracy of quantification. Hughes and colleagues compared image quality [33] of three SPECT/CT systems for cardiac applications. They showed that these systems performed differently in terms of quantitative accuracy, contrast, signal-to-noise, and uniformity. In a different study [34] in which they compared the same three SPECT/CT systems, they showed that image resolution is very much dependent on the reconstruction algorithm. In recent years, various SPECT/CT and software vendors have responded to the increasing need for SPECT quantification and now commercially offer software packages for quantification of several radionuclides including 99mTc, 111In, 131I, and 177Lu [35–38].

The aim of this study is to compare absolute quantification for state-of-the-art SPECT/CT systems from different vendors at different imaging centers for 99mTc. Multiple quantitative reconstruction algorithms that are currently commercially available are included in the comparison. The quantitative accuracy and inter-system variability of recovery coefficients (RC) are determined using various phantom experiments. The effects of lesion volume, patient size, reconstruction algorithm, and post-processing on RC are investigated. The results of these comparisons provide a first step towards a vendor-independent standard for absolute quantitative SPECT/CT that would allow transferability of the obtained metrics [39].

Methods

SPECT/CT systems

Data were acquired on five state-of-the-art SPECT/CT systems from three manufacturers: a Discovery NM/CT 670 Pro (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA), a Precedence 6 (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands), a Symbia Intevo 6, and two Symbia T16’s (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of all used SPECT/CT systems with LEHR collimator

| System | Discovery NM/CT 670 Pro | Precedence 6 | Symbia Intevo 6 | Symbia T16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detector crystal | 3/8” NaI | 3/8” NaI | 3/8” NaI | 3/8” NaI |

| PMT* | 59 | 55 | 59 | 59 |

| FOV* | 40 × 54 cm | 38.1 × 50.8 cm | 38.7 × 53.3 cm | 38.7 × 53.3 cm |

| Hole shape | Hexagonal | Hexagonal | Hexagonal | Hexagonal |

| Number of holes (× 1000) | Not specified | 86.4 | 148 | 148 |

| Collimator hole diameter | 1.50 mm | 1.40 mm | 1.11 mm | 1.11 mm |

| Hole length | 35 mm | 32.8 mm | 24.05 mm | 24.05 mm |

| Septal thickness | 0.2 mm | 0.152 mm | 0.16 mm | 0.16 mm |

| Sensitivity for 99mTc @ 10 cm | 72 cps/MBq | 66 cps/MBq | 91 cps/MBq | 91 cps/MBq |

| Septal penetration @ 140 keV | 0.3% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Planar resolution† | 7.4 mm | 7.4 mm | 7.5 mm | 7.5 mm |

| SPECT central resolution† | 6.4 mm | 4.4 mm | 4.4 mm | 4.4 mm |

| SPECT peripheral radial resolution† | 5.7 mm | 4.2 mm | 4.0 mm | 4.0 mm |

| SPECT peripheral tangential resolution† | 5.1 mm | 4.3 mm | 3.9 mm | 3.9 mm |

* (C)FOV (center) field of view, PMT photomultiplier tube

† Spatial resolution without scatter (LEHR collimator at 10 cm, (full width at half maximum (FWHM) in CFOV [mm], 3/8” crystal)

Phantoms

A NEMA IEC body phantom without lung insert was used (Fig. 1). This phantom represents a patient with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 (which is considered normal) and contains six spheres with inner diameters (and corresponding volumes) of 10 mm (0.5 ml), 13 mm (1.2 ml), 17 mm (2.6 ml), 22 mm (5.6 ml), 28 mm (11.5 ml), and 37 mm (26.5 ml). To evaluate the effect of patient size on SPECT quantification, two additional custom-made phantoms were used on some systems that were similar to the shape of the NEMA IEC body phantom, but with larger diameters, reflecting a larger BMI of obese patients (Table 2). The spheres from the NEMA IEC body phantom were also used for the increased body size phantoms.

Fig. 1.

The phantoms used to determine the RC. Upper phantom: NEMA IEC body phantom. Lower two phantoms: custom-made phantoms reflecting a larger body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) of patients. Note that the lower two phantoms are depicted without spheres inset

Table 2.

Phantom sizes and corresponding patient characteristics

| Phantom | Volume (l) | Waist circumference (cm) | Corresponding patient BMI* (kg/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (NEMA phantom) | 9.70 | 85 | 25 |

| Medium | 14.73 | 100 | 28 |

| Large | 25.96 | 130 | 47 |

* BMI body mass index

For all phantoms, the spheres and background compartment were filled with a homogeneous solution of 99mTc-pertechnetate in water with a concentration of approximately 100 kBq/ml and 10 kBq/ml, respectively, resulting in a sphere-to-background ratio of 10:1 similar to EARL guidelines for 18F-FDG PET imaging [8]. All 99mTc-pertechnetate activities were measured in the clinical radionuclide dose calibrators present in the participating hospitals, which undergo regular quality control according to national guidelines [40].

Data acquisition and reconstruction

Harmonized acquisition protocols were used for all measurements. Images were acquired with a low-energy high-resolution (LEHR) collimator (Table 1) in step and shoot mode, 128 projections (64 per detector head) (Discovery NM/CT 670 Pro: 120 projections, 60 per detector head), 20 s per projection, zoom factor 1.0, matrix size 128 × 128 (Symbia Intevo, 256 × 256), a photon energy window of 140 keV ± 15% and the detector trajectory set to body contour. Data from the standard NEMA phantom were acquired five times repetitively to assess system-specific repeatability. The time per angle was adjusted to obtain similar count statistics for each replicate.

Data were reconstructed with two reconstruction methods to assess its influence on quantification. First, vendor-specific 3D iterative reconstruction algorithms that included scatter correction, CT-based attenuation correction (for acquisition parameters see Additional file 1: Table S1) and resolution recovery with institute-specific settings used in clinical practice [3] were used. This included two quantitative reconstruction algorithms that are currently commercially available (GE Q.Metrix and Siemens xSPECT Quant). Second, data were reconstructed with a vendor-neutral quantitative reconstruction algorithm (Hybrid Recon v1.1.2; Hermes Medical Solutions, Stockholm, Sweden) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reconstruction and quantification parameters and processing software used in this study

| System | Discovery NM/CT 670 Pro | Precedence 6 | Symbia Intevo 6 | Symbia T16 system 1 | Symbia T16 system 2 | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging center | Leiden University Medical Center | Maastricht University Medical Center | Noord West ziekenhuis Groep | Radboud University Medical Center | Erasmus University Medical Center | All |

| Reconstruction | OSEM* + Evolution with PSF* correction | OSEM* + Astonish with PSF* correction | Weighted Conjugate Gradient + xSPECT with PSF* correction | OSEM* + Flash 3D with PSF* correction | OSEM* + Hybrid Recon V1.2 with PSF* correction | OSEM* + Hybrid Recon V1.2 with PSF* correction |

| Quantification | Q.Metrix | Manual analysis | xSPECT Quant | Manual analysis | Hermes SUV SPECT | Hermes SUV SPECT |

| Iterations | 9 [5] | 3 | 24 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Subsets | 10 | 16 | 2 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Post-reconstruction filter | None | None | 7.5 mm (Gaussian) | 8.4 mm (Gaussian) | 5 mm (Gaussian) | 5 mm (Gaussian) |

| Processing | GE Xeleris 4.0 workstation | Philips Extended Brilliance Workspace | Siemens Syngo.via | Siemens Inveon Research Workplace | Hermes Hybrid Viewer | In-house developed Python algorithm |

| Attenuation correction | CT-based, bilinear conversion of HU into attenuation coefficients at 140 keV | CT-based, HU segmentation using a step-like law, bilinear conversion of HU into attenuation coefficients at 140 keV | CT-based, bilinear conversion of HU into attenuation coefficients at 140 keV | CT-based, bilinear conversion of HU into attenuation coefficients at 140 keV | CT-based, Bilinear conversion of HU into attenuation coefficients at 140 keV | CT-based, bilinear conversion of HU into attenuation coefficients at 140 keV |

| Scatter Correction | DEW* (120 keV ± 10%) | Kernel based | DEW* (119 keV ± 7.5%) | DEW* (119 keV ± 10%) | Monte Carlo-based | Monte Carlo-based |

| Image voxel size | 2.21 × 2.21 × 2.21 mm3† | 4.7 × 4.7 × 4.7 mm3 | 2.54 × 2.54 × 2.54 mm3 | 4.8 × 4.8 × 4.8 mm3 | 4.8 × 4.8 × 4.8 mm3 | 4.8 × 4.8 × 4.8 mm3 |

* OSEM ordered subset expectation maximization, PSF point spread function, DEW dual energy window

† Initial acquisition was performed with 128 × 128 matrix size and corresponding voxel size of 4.42 × 4.42 × 4.42 mm3. For quantification purposes this was interpolated to a 256 × 256 matrix size and corresponding voxel size of 2.21 × 2.21 × 2.21 mm3, as recommended by the vendor.

Calibration factor

SPECT/CT systems were cross-calibrated for 99mTc with the corresponding dose calibrators according to the manufacturer’s recommendation or to the center’s standard practice (Additional file 1: Table S2). Either one large or multiple smaller cylindrical regions of interest (ROIs) where drawn to obtain a calibration factor (CF) according to:

| 1 |

where μ is the mean voxel value in the reconstructed image, t is the time per projection, n is the number of projections, ν is the voxel size, and A is the actual activity concentration in the phantom.

Analysis

To evaluate the absolute quantification of different SPECT/CT systems, RC for background and all six spheres were determined. RC was defined as the ratio of the measured activity concentration (a) and the true activity concentration (A) for each sphere:

| 2 |

Volumes of interest (VOIs) for each sphere were determined with a region growing algorithm for which the cut-off threshold was calculated by [41]:

| 3 |

where VVthresh is the threshold voxel value, VVmax,sphere is the maximum voxel value in the sphere VOI, and VVmean,bg is the mean voxel value in the background VOI. VVmean,bg was determined by placing six cylindrical VOIs (diameter 4–5 cm) in a uniform region within the phantom.

The maximum and mean activity concentration for each sphere were determined, which resulted in both maximum and mean RC values, denoted as RCmax and RCmean, respectively.

The repeatability of the RC for each system was assessed with the reconstructed data of the five repetitive measurements by calculating the median absolute deviation (MAD) for each sphere diameter according to:

| 4 |

where RCi is the recovery coefficient of measurement i and is the median recovery coefficient of all repetitive measurements.

The MAD was also used to assess variability between systems for each sphere diameter. For each sphere, the median RC from each system was used in Eq. 4. This resulted in a sphere-specific MAD.

In addition to center-specific image analysis, all images were processed automatically in a standardized way using in-house developed software in Python which uses the SimpleITK toolkit region growing algorithm to determine sphere-specific VOIs using the same region growing algorithm as described above (Table 4) [42, 43].

Table 4.

Calibration factors for center-specific and vendor-neutral reconstructions, calculated for 128 projections and 20 s/projection

| System | Center-specific CF* (cps/kBq) | CF for Hermes SUV SPECT (kBq/cts) |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery NM/CT 670 Pro | 0.075 | 0.128 |

| Precedence 6 | 0.0986 | 0.143 |

| Symbia Intevo 6 | 1.00 [-]† | 0.112 |

| Symbia T16 system 1 | 0.0951 | 0.114 |

| Symbia T16 system 2 | 0.110 | 0.110 |

* CF calibration factor

† Data is already quantitative in kBq therefore no calibration factor is stated

Results

Calibration factor

The calibration factors that were used to determine the RC for each system can be found in Table 4.

Recovery coefficient

Differences (indicated as mean ± standard deviation) between the RC determined using standardized processing software versus center-specific processing software were 2 ± 3% for RCmean and 0 ± 3% RCmax. Since these differences were considered negligible, all data were processed using the standardized processing software (Python) as described earlier (performed centralized by two authors on all data).

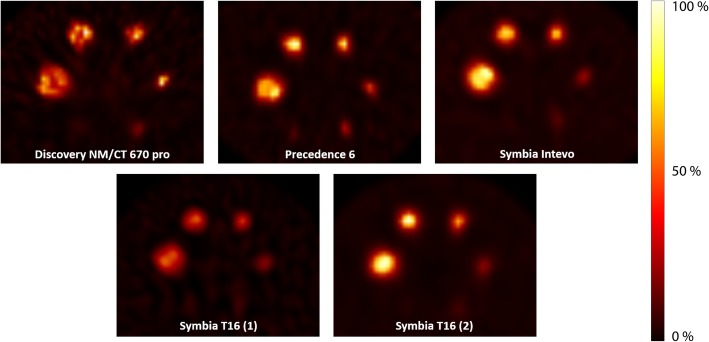

The median recovery coefficient of the background compartment of the phantom was 1.01 (range, 0.93–1.07). The sphere-to-background activity concentration ratio was 10.6 ± 0.4:1 for all systems. Images obtained on all five systems showed different visual results (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Images of the NEMA IEC body phantom for all systems, reconstructed with a vendor-specific algorithm

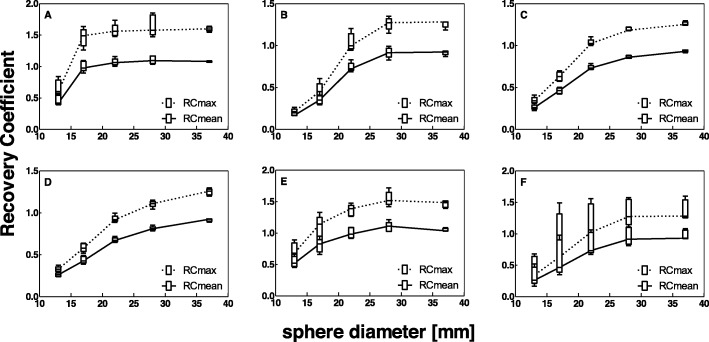

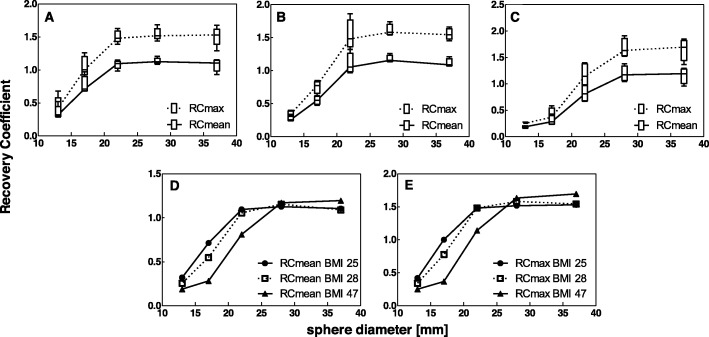

For all systems, both RCmean and RCmax decreased with decreasing sphere diameter (Fig. 3a–e). RC for the smallest sphere diameter (10 mm) could not be obtained because of the low contrast between the smallest sphere and the background for the used activity concentration ratio. Therefore, this sphere diameter is not considered in the remainder of this study. The variability in RC between systems is visualized in Fig. 3f.

Fig. 3.

Recovery coefficient as a function of sphere diameter for all systems separately (a–e) and for all systems combined (f), for data reconstructed with a vendor-specific algorithm. Median and box plot for five repetitive measurements per system. (a) GE Discovery NM/CT 670 Pro, (b) Philips Precedence 6, (c) Siemens Symbia Intevo 6, (d) Siemens Symbia T16 system 1, (e) Siemens Symbia T16 system 2, (f) Median RC values for all systems combined

For each system, RC repeatability, expressed as the MAD, was best for the largest spheres, but good repeatability was shown for all sphere diameters (Table 5).

Table 5.

MAD per system (median and range over all sphere diameters) for data reconstructed using a vendor and center-specific algorithm

| RCmean | RCmax | |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery NM/CT 670 Pro | 0.02 (0.01—0.08) | 0.06 (0.02—0.10) |

| Precendence 6 | 0.02 (0.00—0.04) | 0.03 (0.00—0.06) |

| Symbia Intevo 6 | 0.01 (0.01—0.03) | 0.01 (0.00—0.05) |

| Symbia T16 (1) | 0.02 (0.00—0.04) | 0.02 (0.01—0.05) |

| Symbia T16 (2) | 0.07 (0.00—0.09) | 0.09 (0.03—0.19) |

Effect of reconstruction algorithm on RC

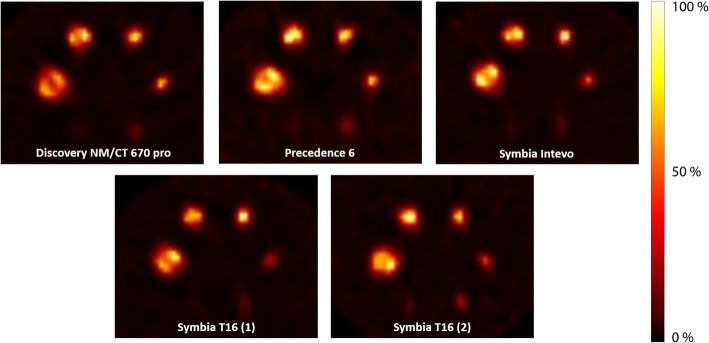

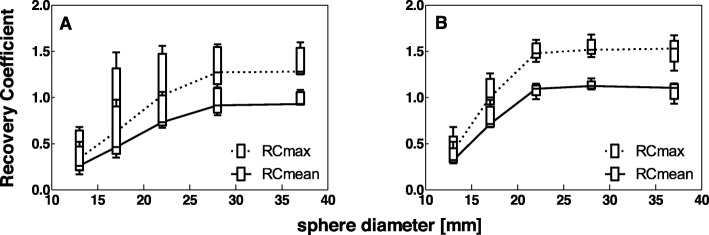

Vendor-neutral reconstruction showed a large decrease in inter-system variability (Figs. 4 and 5). This finding is further confirmed by the MAD for reconstruction with vendor-specific versus vendor-neutral software (Table 6), which shows a median MAD of 0.10 and 0.17 (16 and 17%) for the RCmean and RCmax of vendor-specific reconstruction, and a decreased median MAD of 0.04 and 0.05 (4 and 5%) for the RCmean and RCmax of vendor-neutral reconstruction, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Images of the NEMA IEC body phantom for all systems, reconstructed with a vendor-neutral algorithm

Fig. 5.

Recovery coefficient for all systems combined as a function of sphere diameter for vendor-specific reconstruction (a) and vendor-neutral reconstruction (b)

Table 6.

MAD per sphere diameter for all systems combined, using either vendor-specific or vendor-neutral reconstruction algorithms.

| Sphere diameter |

RCmean | RCmax | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vendor-specific | Vendor-neutral | Vendor-specific | Vendor-neutral | |

| 37 mm | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| 28 mm | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.04 |

| 22 mm | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.06 |

| 17 mm | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.11 |

| 13 mm | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

Effect of patient size on RC

Medium and large phantom data were only reconstructed using a vendor-neutral algorithm, since results for the small phantom showed the smallest variability between systems for these settings. It can be seen in Fig. 6 that variability of RC between systems increased in larger phantom volumes. Furthermore, smaller sphere diameters showed lower quantitative accuracy (lower RC values) indicating that reliable quantification of small volumes (< 10 ml) in larger (patient) volumes is more challenging.

Fig. 6.

RC per sphere diameter for (a) small phantom (BMI, 25 kg/m2), (b) medium phantom (BMI, 28 kg/m2), (c) large phantom (BMI, 47 kg/m2), (d–e) RCmean and RCmax for all three phantom volumes (median only). All data was reconstructed using a vendor-neutral algorithm

Discussion

This study is a considerable step towards standardization of absolute SPECT quantification by investigating the quantitative accuracy of different SPECT/CT systems. The quantitative accuracy of individual SPECT-CT systems was assessed earlier for the GE Discovery NM/CT 670 system [5], the Siemens Symbia Intevo system [44] and the Hermes SUV SPECT quantitative reconstruction algorithm [36]. Although an earlier study by Seret et al. [32] also compared the quantitative capabilities of four SPECT/CT cameras, our study included the current state-of-the-art quantitative SPECT/CT systems that enable absolute quantification that were not available at that time.

Many factors contribute to the uncertainty in quantification even if acquisition protocols are standardized, including VOI outlining methodology, operator variability and activity measurement (dose calibrator uncertainty, cross calibration between dose calibrator, and SPECT/CT system) [45] and in our study also phantom preparation. The median RC in the background compartment was found to be 1.01, which indicated reliable acquisition, reconstruction and analysis. However, for some systems and measurements, the background RC was as low as 0.93 or as high as 1.07. This deviation might of course also influence the sphere RC values and thereby introduce an increase in variability between quantification on different systems. Furthermore, this study showed that the largest contribution for inter-system variation is due to vendor-specific reconstruction settings. Vendor-neutral reconstruction reduced this variation two to threefold (median MAD). It is therefore paramount to harmonize SPECT/CT image reconstructions in a multi-center/multi-vendor setting.

In a clinical setting, it is expected that the variability in quantification between SPECT/CT systems will increase, due to for example patient positioning and patient volume (BMI). To this end, we compared the recovery of the hot spheres in differently sized phantoms on several SPECT/CT systems. Only minor, not clinically relevant differences between the phantoms representing a BMI of 25 and 28 kg/m2 were found, while this change in BMI implies a rather significant increase in patient circumference. We therefore expect that for patients with a normal to slightly increased BMI, it is not necessary to take patient circumference into account for quantification. For a high BMI of 47 kg/m2 on the other hand, activity could not be recovered for the smaller sphere diameters. This might be explained by the increased attenuation, decreased signal-to-noise ratio, and decreased spatial resolution due to increased source-detector distance in these larger volumes. This means that in patients with a high BMI, quantifying smaller lesions will be more challenging. Using more iterations in the reconstruction of images of larger patients might improve convergence and thereby improve resolution and prevent artifacts, which was also shown for SPECT/CT myocardial perfusion studies by Celler et al. [46]. The effect of increased attenuation could be canceled by an increase in scan time per projection or by increasing patient dose. The impact of scan time and dosage on image quality and image quantification is interesting to investigate further, but this was not within our scope.

The phantom used in this study did not contain lung, air, or bone components. Therefore the results mainly reflect quantification accuracy for soft tissue lesions. Experiments were performed using 99mTc-pertechnetate. This radionuclide is the most widely used in SPECT imaging, and quantification of 99mTc holds potential in for example myocardial perfusion imaging [47], functional lung scanning [48], selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) of liver tumors [49, 50], quantification in bone lesions [51, 52], and therapy monitoring in locally advanced breast cancer [5]. In addition, since the radiotracer is widely available, it served as a suitable radionuclide to compare absolute quantification performance of SPECT/CT systems.

In the current study, an activity concentration ratio of 1:10 was used between the background and spheres, based on the ratio used for the same phantom in the EARL accreditation program. With lower activity concentration ratios, lower RC values are expected due to partial volume effects.

For one system, matrix size changes were necessary between vendor-specific and vendor-independent reconstructions. With this change, it is uncertain whether the improved inter-scanner variability is due to the vendor-neutral reconstruction algorithm, or to the change in matrix size. It was, however, the aim of our study to assess whether vendor-neutral reconstruction would improve inter-scanner variability. Which underlying parameter caused this improvement was not the goal of our study.

Both vendor dependent as well as vendor-neutral reconstructions showed Gibbs artifacts for all systems, which is a known result of resolution modeling. These artifacts occur especially in phantom reconstructions, with high contrast changes between different structures. In our study, a large contrast change was present between the inside and outside of the spheres. Despite this large contrast change, and its accompanying Gibbs artifact, all systems showed RCmean values approaching unity for larger sphere sizes. When sphere size decreases, the edge ring artifacts will come very close to each other and eventually merge, resulting in a too high activity in the center of the sphere.

In this study, only one vendor-neutral reconstruction algorithm was used. In theory, another reconstruction algorithm, although not commercially available at this moment, could potentially influence the resulting metrics. For the current study, however, our aim was to assess the influence of the reconstruction algorithm on RC measurements which could be assessed by using a vendor-neutral algorithm.

Knowledge gained from this study can be used to assess the absolute quantitative accuracy for other radionuclides as well. This can serve as input for a standardization program for absolute SPECT quantification which can be used to improve sophisticated clinical dosimetry in radionuclide therapy studies, especially in a multi-center setting.

Conclusion

This study shows that absolute SPECT quantification is feasible in a multi-center and multi-vendor setting. With center-specific reconstructions, variability between systems was 0.01–0.20 and 0.03–0.28 (MAD) for RCmean and RCmax, respectively. Standardized reconstruction decreases this variability to 0.02–0.05 and 0.04–0.11. Variation between centers is mainly caused by the use of different reconstruction algorithms and/or settings. Patient size showed to be relevant for quantification, as it was observed that high patient volume (BMI 47 kg/m2) resulted in an increased variability among systems and impeded quantification of small lesions (< 10 ml). Close agreement between vendors and centers is key for reliable multi-center dosimetry and quantitative biomarker studies. This study serves as a first step towards a vendor-independent standard for absolute quantification in SPECT/CT.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Settings of low dose CT protocols used for attenuation correction. Table S2. Cross-calibration protocols for dose calibrators to SPECT/CT system according to vendor recommendations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Evert-Jan Woudstra and Antoi Meeuwis for their contribution in acquiring data.

Abbreviations

- 111In

Indium-111

- 131I

Iodine-131

- 177Lu

Lutetium-177

- 90Y

Yttrium-90

- 99mTc

Technetium-99m

- BMI

Body mass index

- CF

Calibration factor

- CT

Computed tomography

- DEW

Dual energy window

- EARL

EANM Research Ltd.

- FDG

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- LEHR

Low-energy high-resolution

- MAD

Median absolute deviation

- OSEM

Ordered subset expectation maximization

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PSF

Point spread function

- RC

Recovery coefficient

- RCmax

Max recovery coefficient

- RCmean

Mean recovery coefficient

- ROI

Region of interest

- SIRT

Selective internal radiation therapy

- SPECT

Single-photon emission computed tomography

- TEW

Triple energy window

- VOI

Volume of interest

Author’s contributions

All authors were involved in the experimental design and analysis and interpretation of the data. SMBP performed measurements for Radboud University Medical Center and took the lead in writing this manuscript. NRvdW, MS and MK performed measurements for Erasmus Medical Center. Additionally, NRvdW took the lead in analyzing the data and MS was responsible for writing the Python code. FHPvV and JAKB performed measurements for Leiden University Medical Center. SVL performed measurements for Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep. EV and MG took the (initial) lead in the design of this study. All authors were involved in writing and reviewing the manuscript, and they all read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement no. 602812 (BetaCure).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Steffie M. B. Peters and Niels R. van der Werf contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s40658-019-0268-5.

References

- 1.Zanzonico PB, Bigler RE, Sgouros G, Strauss A. Quantitative SPECT in radiation dosimetry. Seminars in nuclear medicine. Elsevier; 1989. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Potrebko PS, Shridhar R, Biagioli MC, Sensakovic WF, Andl G, Poleszczuk J, et al. SPECT/CT image-based dosimetry for Yttrium-90 radionuclide therapy: application to treatment response. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics. 2018;19(5):435–443. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey DL, Willowson KP. An evidence-based review of quantitative SPECT imaging and potential clinical applications. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(1):83–89. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.111476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey DL, Willowson KP. Quantitative SPECT/CT: SPECT joins PET as a quantitative imaging modality. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2014;41(1):17–25. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collarino A, Pereira Arias-Bouda LM, Valdés Olmos RA, van der Tol P, Dibbets-Schneider P, de Geus-Oei LF, et al. Experimental validation of absolute SPECT/CT quantification for response monitoring in breast cancer. Medical physics. 2018;45(5):2143–2153. doi: 10.1002/mp.12880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandervoort E, Celler A, Harrop R. Implementation of an iterative scatter correction, the influence of attenuation map quality and their effect on absolute quantitation in SPECT. Physics in Medicine & Biology. 2007;52(5):1527. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/5/020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boellaard R, O’Doherty MJ, Weber WA, Mottaghy FM, Lonsdale MN, Stroobants SG, et al. FDG PET and PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour PET imaging: version 1.0. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2010;37(1):181. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1297-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boellaard R, Delgado-Bolton R, Oyen WJ, Giammarile F, Tatsch K, Eschner W, et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: version 2.0. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2015;42(2):328–354. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2961-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewaraja YK, Frey EC, Sgouros G, Brill AB, Roberson P, Zanzonico PB, et al. MIRD pamphlet no. 23: quantitative SPECT for patient-specific 3-dimensional dosimetry in internal radionuclide therapy. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2012;53(8):1310–1325. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.100123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmadzadehfar H, Rahbar K, Kürpig S, Bögemann M, Claesener M, Eppard E, et al. Early side effects and first results of radioligand therapy with 177 Lu-DKFZ-617 PSMA of castrate-resistant metastatic prostate cancer: a two-centre study. EJNMMI research. 2015;5(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13550-015-0114-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delker A, Fendler WP, Kratochwil C, Brunegraf A, Gosewisch A, Gildehaus FJ, et al. Dosimetry for 177 Lu-DKFZ-PSMA-617: a new radiopharmaceutical for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2016;43(1):42–51. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabasakal L, AbuQbeitah M, Aygün A, Yeyin N, Ocak M, Demirci E, et al. Pre-therapeutic dosimetry of normal organs and tissues of 177 Lu-PSMA-617 prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) inhibitor in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2015;42(13):1976–1983. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kratochwil C, Giesel FL, Stefanova M, Benesova M, Bronzel M, Afshar-Oromieh A, et al. PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with Lu-177 labeled PSMA-617. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(8):1170–1176. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.171397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luster M, Clarke S, Dietlein M, Lassmann M, Lind P, Oyen W, et al. Guidelines for radioiodine therapy of differentiated thyroid cancer. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2008;35(10):1941. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0883-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sgouros G, Kolbert KS, Sheikh A, Pentlow KS, Mun EF, Barth A, et al. Patient-specific dosimetry for 131I thyroid cancer therapy using 124I PET and 3-dimensional-internal dosimetry (3D-ID) software. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2004;45(8):1366–1372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodei L, Cremonesi M, Ferrari M, Pacifici M, Grana CM, Bartolomei M, et al. Long-term evaluation of renal toxicity after peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 90 Y-DOTATOC and 177 Lu-DOTATATE: the role of associated risk factors. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2008;35(10):1847–1856. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0778-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cives M, Strosberg J. Radionuclide therapy for neuroendocrine tumors. Current oncology reports. 2017;19(2):9. doi: 10.1007/s11912-017-0567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strosberg JR, Wolin EM, Chasen B, Kulke MH, Bushnell DL, Caplin ME, et al. NETTER-1 phase III: progression-free survival, radiographic response, and preliminary overall survival results in patients with midgut neuroendocrine tumors treated with 177-Lu-Dotatate. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, Hendifar A, Yao J, Chasen B, et al. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(2):125–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldherr C, Pless M, Maecke HR, Schumacher T, Crazzolara A, Nitzsche EU, et al. Tumor response and clinical benefit in neuroendocrine tumors after 7.4 GBq 90Y-DOTATOC. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2002;43(5):610–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bastiaannet R, van der Velden S. Lam MG. Viergever MA: de Jong HW. Fast and accurate quantitative determination of the lung shunt fraction in hepatic radioembolization. Physics in Medicine & Biology; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeintl J, Vija AH, Yahil A, Hornegger J, Kuwert T. Quantitative accuracy of clinical 99mTc SPECT/CT using ordered-subset expectation maximization with 3-dimensional resolution recovery, attenuation, and scatter correction. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(6):921. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.071571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakahara T, Daisaki H, Yamamoto Y, Iimori T, Miyagawa K, Okamoto T, et al. Use of a digital phantom developed by QIBA for harmonizing SUVs obtained from the state-of-the-art SPECT/CT systems: a multicenter study. EJNMMI research. 2017;7(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13550-017-0300-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assie K, Dieudonné A, Gardin I, Vera P, Buvat I. A preliminary study of quantitative protocols in Indium 111 SPECT using computational simulations and phantoms. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 2010;57(3):1096–1104. doi: 10.1109/TNS.2010.2041252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He B, Du Y, Song X, Segars WP, Frey EC. A Monte Carlo and physical phantom evaluation of quantitative In-111 SPECT. Physics in Medicine & Biology. 2005;50(17):4169. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/17/018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He B, Frey EC. Comparison of conventional, model-based quantitative planar, and quantitative SPECT image processing methods for organ activity estimation using In-111 agents. Physics in Medicine & Biology. 2006;51(16):3967. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/16/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green AJ, Dewhurst SE, Begent RH, Bagshawe KD, Riggs SJ. Accurate quantification of 131 I distribution by gamma camera imaging. European journal of nuclear medicine. 1990;16(4-6):361–365. doi: 10.1007/BF00842793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beauregard J-M, Hofman MS, Pereira JM, Eu P, Hicks RJ. Quantitative 177Lu SPECT (QSPECT) imaging using a commercially available SPECT/CT system. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11(1):56. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2011.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siman W, Mikell JK, Kappadath SC. Practical reconstruction protocol for quantitative (90)Y bremsstrahlung SPECT/CT. Medical physics. 2016;43(9):5093. doi: 10.1118/1.4960629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ljungberg M, Frey E, Sjögreen K, Liu X, Dewaraja Y, Strand S-E. 3D absorbed dose calculations based on SPECT: evaluation for 111-In/90-Y therapy using Monte Carlo simulations. Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2003;18(1):99–107. doi: 10.1089/108497803321269377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ljungberg M, Sjögreen K, Liu X, Frey E, Dewaraja Y, Strand S-E. A 3-dimensional absorbed dose calculation method based on quantitative SPECT for radionuclide therapy: evaluation for 131I using Monte Carlo simulation. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2002;43(8):1101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seret A, Nguyen D, Bernard C. Quantitative capabilities of four state-of-the-art SPECT-CT cameras. EJNMMI research. 2012;2(1):45. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-2-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes T, Celler A. A multivendor phantom study comparing the image quality produced from three state-of-the-art SPECT-CT systems. Nuclear medicine communications. 2012;33(6):663–670. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328351d549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes T, Shcherbinin S, Celler A. A multi-center phantom study comparing image resolution from three state-of-the-art SPECT-CT systems. Journal of nuclear cardiology. 2009;16(6):914. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NM Quantification Q.Metrix for SPECT/CT Package. White Paper DOC1951185: GE Healthcare.

- 36.Kangasmaa TS, Constable C, Hippeläinen E, Sohlberg AO. Multicenter evaluation of single-photon emission computed tomography quantification with third-party reconstruction software. Nuclear medicine communications. 2016;37(9):983–987. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Accurate, reproducible, and standardized quantification. xSPECT Quant White Paper: Siemens Healthineers.

- 38.Armstrong IS, Hoffmann SA. Activity concentration measurements using a conjugate gradient (Siemens xSPECT) reconstruction algorithm in SPECT/CT. Nuclear medicine communications. 2016;37(11):1212–1217. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dickson J, Ross J, Vöö S. Quantitative SPECT: the time is now. EJNMMI physics. 2019;6(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40658-019-0241-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medicine DSoN. Procedure guidelines nuclear medicine. Part IV: Equipment: Kloosterhof Neer BV. 2016:662–70.

- 41.Frings V, de Langen AJ, Smit EF, van Velden FH, Hoekstra OS, van Tinteren H, et al. Repeatability of metabolically active volume measurements with 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT PET in non–small cell lung cancer. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2010;51(12):1870–1877. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.077255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowekamp BC, Chen DT, Ibáñez L, Blezek D. The design of SimpleITK. Frontiers in neuroinformatics. 2013;7:45. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2013.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yaniv Z, Lowekamp BC, Johnson HJ, Beare R. SimpleITK image-analysis notebooks: a collaborative environment for education and reproducible research. Journal of digital imaging. 2018;31(3):290–303. doi: 10.1007/s10278-017-0037-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gnesin S, Leite Ferreira P, Malterre J, Laub P, Prior JO, Verdun FR. Phantom validation of Tc-99m absolute quantification in a SPECT/CT commercial device. Computational and mathematical methods in medicine. 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Gear JI, Cox MG, Gustafsson J, Gleisner KS, Murray I, Glatting G, et al. EANM practical guidance on uncertainty analysis for molecular radiotherapy absorbed dose calculations. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2018;45(13):2456–2474. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Celler A, Shcherbinin S, Hughes T. An investigation of potential sources of artifacts in SPECT-CT myocardial perfusion studies. Journal of nuclear cardiology. 2010;17(2):232–246. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Da Silva AJ, Tang HR, Wong KH, Wu MC, Dae MW, Hasegawa BH. Absolute quantification of regional myocardial uptake of 99mTc-sestamibi with SPECT: experimental validation in a porcine model. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;42(5):772–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohno Y, Koyama H, Nogami M, Takenaka D, Matsumoto S, Yoshimura M, et al. Postoperative lung function in lung cancer patients: comparative analysis of predictive capability of MRI, CT, and SPECT. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2007;189(2):400–408. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dittmann HJ, Kopp D, Kupferschlaeger J, Feil D, Groezinger G, Syha R, et al. A prospective study of quantitative SPECT/CT for evaluation of hepatopulmonary shunt fraction prior to SIRT of liver tumors. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Dittmann H, Kopp D, Kupferschlaeger J, Feil D, Groezinger G, Syha R, et al. A prospective study of quantitative SPECT/CT for evaluation of lung shunt fraction before SIRT of liver tumors. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2018;59(9):1366–1372. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.205203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Israel O, Hardoff R, Ish-Shalom S, Jerushalmi J, Kolodny GM. In vivo SPECT quantitation of bone metabolism in hyperparathyroidism and thyrotoxicosis. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1991;32(6):1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamane T, Kuji I, Seto A, Matsunari I. Quantification of osteoblastic activity in epiphyseal growth plates by quantitative bone SPECT/CT. Skeletal radiology. 2018:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Settings of low dose CT protocols used for attenuation correction. Table S2. Cross-calibration protocols for dose calibrators to SPECT/CT system according to vendor recommendations.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.