To the Editor,

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), bloodstream infection (BSI), and pulmonary complications (PCs) occur in ~15% [1], 20% [2], and 70% [3] of allogeneic HCT recipients, respectively. Although these conditions seem disparate, a common factor implicated in their pathogenesis is alterations in gut barrier integrity. Microbial translocation through the gut barrier is the hallmark event in most BSIs after HCT [4]. In addition, the gut barrier is a key component of the “gut-lung axis” implicated in PCs [3, 5]. Finally, tight junctions between the epithelial cells contribute to gut barrier integrity by separating different compartments of the cell membrane and limiting the diffusion of receptors between luminal and basolateral compartments [6]. Binding of C. difficile toxin, released in the lumen, to its receptor on the basolateral membrane, a prerequisite for C. difficile colonization and enterotoxicity [7, 8], requires tight junction disruption.

Zonulin, the precursor for haptoglobin-2, is the only physiological mediator known to regulate intestinal tight junctions [9]. Zonulin-induced disengagement of zonula occludens 1 from the tight junctional complex results in tight junction disassembly and increased permeability [10]. The presence of one or both HP α-chains determines the polymorphic HP genotypes HP1–1, HP2–1, and HP2–2 [11]. Homozygous HP1–1 individuals (~16% of the Western population [12]) are not able to make zonulin. Although zonulin has been implicated in chronic inflammatory conditions (both intestinal and extra-intestinal), it has not been studied in the HCT setting [13]. We hypothesized that a presumed less “leaky” gut barrier will prevent C. difficile toxin access to its receptor on the basolateral membrane and limit bacterial translocation, thereby decreasing the incidence of CDI, BSI, and PCs. We tested this hypothesis by comparing the incidence of CDI, BSI, and PCs in patients with the “no-zonulin” genotype HP1–1 to those with the other two genotypes (HP2–1 or HP2–2).

All patients had received their inpatient and outpatient care at the University of Minnesota (inpatient transplant unit and outpatient transplant clinic). We retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records of all consecutive patients (2009–2017) with the following inclusion criteria: (i) first allograft, (ii) underlying diagnosis of AML or ALL, (iii) HLA-matched sibling or unrelated donor; or umbilical cord blood, and (iv) cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells collected between admission and day 0 and available for research (see below). We chose (i–iii) to increase the homogeneity of our cohort concerning factors that may influence susceptibility to the outcomes of interest. For example, acute leukemia patients have typically experienced more damage to their gut barrier before HCT than lymphoma patients and may be at higher risk for gut barrier-related complications. We did not include HLA-haploidentical recipients because we seldom used this donor type in the period of our study. We use levofloxacin (starting day −1) for antibacterial prophylaxis and cefepime as empiric antibiotic for neutropenic fever. Deviations from this algorithm may occur at the discretion of the treating physicians. PC was defined by new abnormal parenchymal findings on chest imaging in the setting of respiratory signs and/or symptoms [3]. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (IPS) was defined according to standard criteria [14]: (i) Widespread alveolar injury defined as multilobar opacities on CT scan plus signs and symptoms of pneumonia plus evidence of abnormal pulmonary physiology (e.g., increased alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient or supplemental oxygen need). All CT scans before day +100 were reviewed by a radiologist masked to the genotyping results who provided the top 3 differential diagnoses. One of the authors, blinded to genotype data, combined radiographic and clinical data to assign final clinical diagnoses. CDI was defined as lower gastrointestinal symptoms associated with a positive PCR for C. difficile toxin B gene (Xpert C. difficile assay; Cepheid GeneXpert). Clinical testing was performed in case of diarrhea and at the discretion of the treating physician. We collected data on antibiotic use within 7 days prior to testing and stool output on the day of testing. BSI included only microbiologically confirmed cases.

Cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells collected between admission and day 0 on a completed, IRB-approved, prospective biorepository study were retrieved and submitted for PCR-based HP gene sequencing as described previously [15]. The consent to the biorepository study included permission for future genetic testing related to infectious complications. All other data (clinical, radiographic, and laboratory) were collected retrospectively. OS was estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves. Relapse, acute GVHD, NRM, BSI, CDI, IPS, and PC rates were estimated using cumulative incidence, treating relapse (for NRM) and non-outcome related death (for all other outcomes) as competing risks. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated. The decision to compare HP1–1 to other genotypes was made a priori. All statistical analyses were performed in R 3.4 (Vienna, Austria).

A total of 157 patients were included (Table S1). Consistent with the expected frequency of the HP1–1 genotype, 27 (17%) patients were HP1–1 and the remaining 130 (83%) had at least one HP2 allele. Antibiotic exposure was not different between the groups with different genotypes (Table S2). Fifty (32%) patients developed a PC by day +100, 45% of which were infectious, followed by IPS (34%), and DAH (10%). Comparing the groups with HP1–1 (unable to produce zonulin) vs. HP1–2/2–2 (able to produce zonulin), 6-month cumulative incidence of acute GVHD grade II-IV was 44% vs. 47% (HR 0.84 [0.45–1.56], P = 0.58), 6-month cumulative incidence of acute GVHD grade III-IV was 15% vs. 21% (HR 0.66 [0.23–1.89], P = 0.44), 6-month cumulative incidence of NRM was 11% vs. 16% (HR 0.85 [0.33–2.17], P = 0.73), and 6-month OS was 70% vs. 77% (HR 1.00 [0.53–1.92], P = 0.99) (Fig. S1).

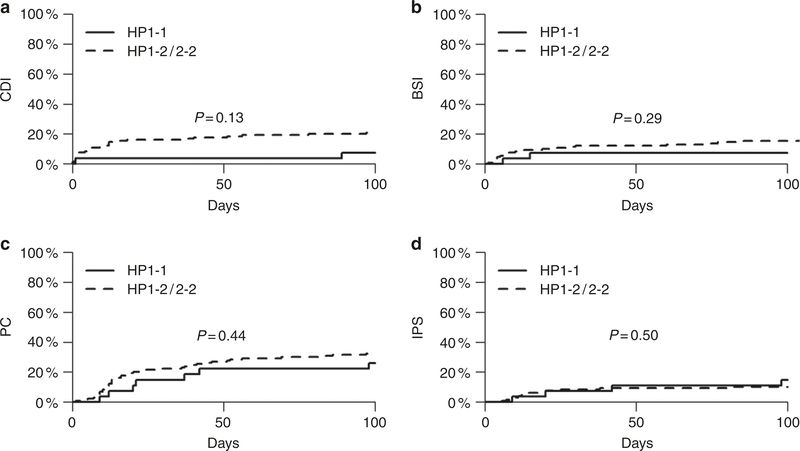

The most suggestive association was found for CDI. The 100-day cumulative incidence of CDI was 3 times lower in the HP1–1 group (7% vs. 21%; HR 0.33 [0.08–1.39]), but the association did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.13) (Fig. 1a). Importantly, the groups with different genotypes had comparable stool volume on the day of C. difficile testing (mean [standard deviation, SD]: 659 [733] mL in HP1–1 vs. 627 [685] mL in HP1–2/2–2 patients; P = 0.87, two-sided t-test). This finding argues against a hypothesis that HP1–2/2–2 patients had larger stool volumes due to their genotype per se, thereby resulting in more C. difficile testing and more frequent positive results. In addition, the stool volume on the day of C. difficile testing in patients with vs. without CDI was similar (544 [736] vs. 657 [677] mL, respectively; P = 0.49, two-sided t-test), suggesting that more C. difficile positivity was not due to more frequent testing because of larger stool volumes per se. We found no significant association between the HP genotype and 100-day cumulative incidence of BSI (P = 0.29), PCs (P = 0.44), and IPS (P = 0.50) (Fig. 1b–d).

Fig. 1.

Association between HP genotype and gut barrier-relevant transplant outcomes. The 100-day cumulative incidence of C. difficile infection (CDI) was 3 times lower in the HP1–1 group, but the association did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.13) (a). There were no significant associations between HP genotype and 100-day cumulative incidence of bloodstream infection (BSI; b), pulmonary complication (PC; c), and idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (IPS; d)

CDI is the leading cause of hospital-acquired infectious diarrhea. Most CDI episodes occur before day +30 [16], as evident in this cohort. The hypothesis leading to the selection of HP as target gene was biologically inspired, and the 95%CI for HR (0.08–1.39) suggests a protective effect against CDI in patients unable to produce zonulin. We elected to study the genotype rather than circulating levels of zonulin because genetic inability to synthesize zonulin is unequivocally predictive of zonulin absence. The only other genetic correlate of CDI, though not studied in allo-HCT, is a single nucleotide polymorphism in the −251 promoter region of the IL-8 gene, resulting in higher fecal levels of IL-8, more potent recruitment of neutrophils, and higher levels of inflammation [17].

Limitations of this work include its retrospective design, small sample size, and potential inaccuracy in stool volume recordings. Future mechanistic studies and larger cohorts are needed to further evaluate our results. The absence of an association in our analysis despite biological rationale could be related to physiological redundancy by which other mechanisms may at least partially compensate for zonulin absence in HP1–1 patients and preserve gut barrier integrity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the University of Minnesota Genomics Center for performing HP sequencing. This study was funded by a Marrow on the Move Award at the University of Minnesota to AR, an American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation New Investigator Award to AR, NIH P30 CA77598 utilizing the Biospecimen Repository in the Translational Therapy Laboratory and Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Core Shared Resources of the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1-TR002494. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-019-0540-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Willems L, Porcher R, Lafaurie M, Casin I, Robin M, Xhaard A, et al. Clostridium difficile infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2012;18:1295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almyroudis NG, Fuller A, Jakubowski A, Sepkowitz K, Jaffe D, Small TN, et al. Pre-and post-engraftment bloodstream infection rates and associated mortality in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2005;7:11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris B, Morjaria SM, Littmann ER, Geyer AI, Stover DE, Barker JN, et al. Gut Microbiota Predict Pulmonary Infiltrates after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:450–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamburini FB, Andermann TM, Tkachenko E, Senchyna F, Banaei N, Bhatt AS. Precision identification of diverse bloodstream pathogens in the gut microbiome. Nat. Med. 2018. 10.1038/s41591-018-0202-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haak BW, Littmann ER, Chaubard J-L, Pickard AJ, Fontana E, Adhi F, et al. Impact of gut colonization with butyrate producing microbiota on respiratory viral infection following allo-HCT. Blood 2018; 131: blood-2018–01-828996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasendra M, Barrile R, Leuzzi R, Soriani M. Clostridium difficile toxins facilitate bacterial colonization by modulating the fence and gate function of colonic epithelium. J Infect Dis. 2014; 209:1095–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stubbe H, Berdoz J, Kraehenbuhl JP, Corthésy B. Polymeric IgA is superior to monomeric IgA and IgG carrying the same variable domain in preventing Clostridium difficile toxin A damaging of T84 monolayers. J Immunol. 2000;164:1952–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tripathi A, Lammers KM, Goldblum S, Shea-Donohue T, Netzel-Arnett S, Buzza MS, et al. Identification of human zonulin, a physiological modulator of tight junctions, as prehaptoglobin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16799–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Asmar R, Panigrahi P, Bamford P, Berti I, Not T, Coppa GV, et al. Host-dependent zonulin secretion causes the impairment of the small intestine barrier function after bacterial exposure. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1607–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowman BH, Kurosky A. Haptoglobin: the evolutionary product of duplication, unequal crossing over, and point mutation. Adv Hum Genet. 1982;12:189–261, 453–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langlois MR, Delanghe JR. Biological and clinical significance of haptoglobin polymorphism in humans. Clin Chem. 1996;42:1589–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sturgeon C, Fasano A. Zonulin, a regulator of epithelial and endothelial barrier functions, and its involvement in chronic inflammatory diseases. Tissue Barriers. 2016;4:e1251384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark JG, Hansen JA, Hertz MI, Parkman R, Jensen L, Peavy HH. NHLBI workshop summary. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after bone marrow transplantation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:1601–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch W, Latz W, Eichinger M, Roguin A, Levy AP, Schömig A, et al. Genotyping of the common haptoglobin Hp 1/2 polymorphism based on PCR. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1377–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chopra T, Chandrasekar P, Salimnia H, Heilbrun LK, Smith D, Alangaden GJ. Recent epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection during hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2011;25: E82–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Z-D, DuPont HL, Garey K, Price M, Graham G, Okhuysen P, et al. A common polymorphism in the interleukin 8 gene promoter is associated with Clostridium difficile diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1112–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.