Abstract

Background/Aims

In the Republic of Korea, an estimated 231,000 individuals have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The aim of the present analysis was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of elbasvir/grazoprevir (EBR/GZR) administered for 12 weeks in Korean patients who were enrolled in international clinical trial phase 3 studies.

Methods

This was a retrospective, integrated analysis of data from patients with HCV genotype (GT) 1b infection enrolled at Korean study sites in four EBR/GZR phase 3 clinical trials. Patients were treatment-naive or had previously failed interferon-based HCV therapy, and included those with human immunodeficiency virus coinfection or Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis. All patients received EBR 50 mg/GZR 100 mg once daily for 12 weeks. The primary endpoint was sustained virologic response at 12 weeks after completion of therapy (SVR12, HCV RNA <15 IU/mL).

Results

SVR12 was achieved by 73 of 74 (98.6%) patients. No patients had virologic failure and one discontinued from the study after withdrawing consent. SVR12 rates were uniformly high across all patient subgroups. A total of 16 patients had nonstructural protein 5A resistance-associated substitutions at baseline (16/73, 22%), all of whom achieved SVR12. Adverse events (AEs) reported in >5% of patients were fatigue (6.8%), upper respiratory tract infection (5.4%), headache (5.4%), and nausea (5.4%). Thirteen patients (17.6%) reported drug-related AEs, two serious AEs occurred, and two patients discontinued treatment owing to an AEs.

Conclusions

In this retrospective analysis, EBR/GZR administered for 12 weeks was well-tolerated and highly effective in Korean patients with HCV GT1b infection.

Keywords: Hepatitis C, Chronic; Antiviral agents; Sustained virologic response

INTRODUCTION

In Korea, an estimated 231,000 individuals have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, accounting for 0.5% of the total population [1]. Infection is more common among older people, with prevalence rates reaching 1.53% in those aged 60–69 years and 2.31% in those aged ≥70 years [2]. Approximately 45% of HCV-infected individuals have genotype (GT) 1b infection and a similar proportion have HCV GT2 infection [1]. HCV infection accounts for 15–20% of all chronic liver disease in Korea [3]. Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents for the treatment of HCV infection are available, and currently there are a total of six different all-oral regimens available for patients with GT1b infection, which vary in duration (12 weeks vs. 8 weeks) and requirement for coadministration of ribavirin according to variables such as treatment history, baseline viral load of HCV, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection [4].

Elbasvir (EBR, MK-8742)/grazoprevir (GZR, MK-5172) is a oncedaily, fixed-dose combination tablet for the treatment of patients with HCV GT1 or GT4 infection. The combination of EBR 50 mg/ GZR 100 mg has broad activity against most HCV GTs in vitro [5-7] and has consistently demonstrated high levels of efficacy and safety in a broad cross-section of people with HCV infection, including treatment-naive and treatment-experienced individuals and those with cirrhosis, HIV coinfection, or chronic kidney disease [8-13]. In Korea, EBR/GZR is recommended for individuals with HCV GT1 or GT4 infection, with a 12-week regimen recommended for all people with HCV GT1b infection, regardless of baseline demographics or disease characteristics [4]. Racial or ethnic background has been reported to impact the efficacy of DAA treatments for HCV infection [14], and EBR/GZR plasma levels are known to be higher in Asian compared with white individuals with HCV infection [15]. We have therefore assessed the clinical profile of EBR/ GZR in people from Korea, focusing on those with HCV GT1b infection, one of the most common HCV GTs in Korea. The aim of the present analysis was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of EBR/GZR administered for 12 weeks in Korean patients who were enrolled in four international phase 3 studies of EBR/GZR.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

This is a retrospective, post hoc, integrated analysis of data from patients with HCV GT1b infection enrolled at Korean study sites in the EBR/GZR clinical development program. All patients were enrolled in the C-EDGE Treatment-Naive [8] (NCT02105467/Protocol PN060), C-CORAL [13] (NCT02251990/PN067), C-SURFER11 (NCT02092350/ PN052), and C-EDGE Treatment-Experienced [9] (NCT02105701/ PN068) studies. All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, current guidelines on Good Clinical Practices, and local ethical and legal requirements, and all patients provided written informed consent prior to any study-related procedures. The methodology and primary outcomes from these studies have been published previously [8,9,11,13].

Patients

Patients included in this analysis were aged >18 years with chronic HCV GT1b infection and a baseline viral load >10,000 IU/mL. Patients were treatment-naive or had previously failed interferonbased HCV therapy, and included those with HIV coinfection or Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis (defined as METAVIR F4 on liver biopsy within 24 months of enrollment; FibroScan® (Echosens, Paris, France) >12.5 kPa within 12 months of enrollment; or aspartate aminotransferase [AST]-to-platelet ratio >2.0 and FibroTest® >0.75). Patients with decompensated liver disease (as indicated by a presence or history of ascites, esophageal or gastric variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy or other signs of advanced liver disease), or evidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were excluded from the original treatment studies. People who had previously received DAA therapy were also excluded from these studies.

Treatment

All patients received EBR 50 mg/GZR 100 mg once daily, administered either as a coformulated fixed-dose combination tablet or as separate entities for 12 weeks. All patients were followed for 24 weeks after cessation of study therapy.

Outcomes

The primary end point was HCV RNA <15 IU/mL at 12 weeks after completion of therapy (sustained virologic response [SVR] at 12 weeks after completion of therapy, SVR12).

Procedures

Plasma HCV RNA levels were measured using the cobas® AmpliPrep/cobas® TaqMan® HCV test (version 2.0, Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ, USA) with a lower limit of quantitation of 15 IU/mL. Relapse was defined as HCV RNA >15 IU/mL during follow-up after HCV RNA <15 IU/mL at the end of treatment. Determination of HCV GT was conducted using the Versant HCV genotype assay (LiPA) 2.0 (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) or the Abbott RealTime HCV Genotype II assay (Abbott Molecular Inc., Abbott Park, IL, USA). Resistance analyses were performed using population sequencing with a limit of minority variant detection >20% of the viral population. Nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) were defined as any polymorphism at amino acid positions 28, 30, 31, and 93.

Analyses

This is a retrospective analysis of data from four international phase 3 clinical trials. Efficacy analyses were performed on the full analysis set (FAS) population (which included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of drug) and the modified FAS (mFAS) population (which excluded patients who discontinued treatment for reasons unrelated to study drug). Safety analyses included all patients who received at least one dose of study medication. Resistance analyses were conducted in all patients with baseline sequencing and a treatment outcome of either SVR12 or virologic failure.

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 74 Korean patients originally enrolled in the C-EDGE Treatment-Naive [8] (n=36), C-CORAL [13] (n=31), C-SURFER [11] (n=4), and C-EDGE Treatment-Experienced [9] (n=3) studies were included in this analysis. Most (n=70, 94.6%) were treatment naive, and all had HCV GT1b infection (Table 1). Twenty-five (33.8%) had cirrhosis and 34 (45.9%) had a baseline viral load >2,000,000 IU/mL. No patients in this analysis had HCV/HIV coinfection.

Table 1.

Patients demographics

| Characteristic | Korean patients (n=74) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 42 (56.8) |

| Male | 32 (43.2) |

| Asian race | 74 (100) |

| HCV GT1b | 74 (100) |

| Age (years) | 55.0±11.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2±3.3 |

| Treatment history | |

| Treatment-naive | 70 (94.6) |

| Treatment-experienced | 4 (5.4) |

| Cirrhosis* | 25 (33.8) |

| HCV/HIV coinfection | 0 (0) |

| Baseline viral load | |

| >800,000 IU/mL | 54 (73.0) |

| >2,000,000 IU/mL | 34 (45.9) |

| IL28B genotype | |

| CC | 60 (81.1) |

| Non-CC | 14 (18.9) |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or n (%).

HCV, hepatitis C virus; GT, genotype; BMI, body mass index; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

In the original treatment studies, the presence of cirrhosis was defined as METAVIR F4 on liver biopsy within 24 months of enrollment, FibroScan® >12.5 kPa within 12 months of enrollment, or a combination of FibroTest® score >0.75 and aspartate aminotransferase:platelet ratio index >2.

Virologic response

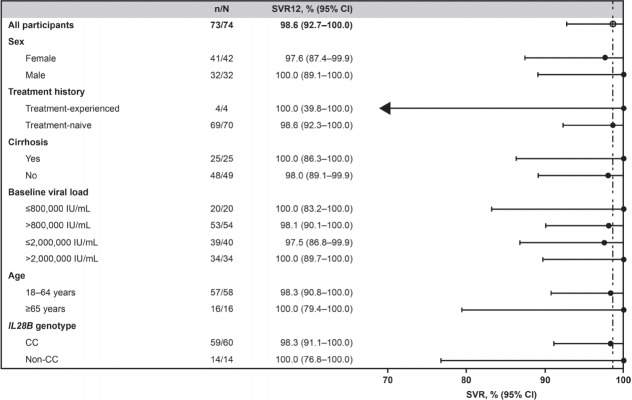

SVR12 was achieved by 73 of 74 (98.6%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 92.7–99.9%) Korean patients with HCV GT1b infection receiving EBR/GZR for 12 weeks in the FAS population (Fig. 1). No patients had virologic failure and one patient discontinued from the study after withdrawing consent. This patient was excluded from the mFAS analysis, resulting in an SVR12 rate in the mFAS population of 100% (73/73).

Figure 1.

SVR12 rates. Virologic outcome of patients treated with elbasvir (EBR)/grazoprevir (GZR). SVR12, sustained virologic response (SVR) at 12 weeks after completion of therapy; FAS, full analysis set; mFAS, modified FAS; AE, adverse event. * Includes all patients who received at least one dose of study medication; † Excludes patients who discontinued treatment for reasons unrelated to study medication; ‡ One patient withdrew consent and did not achieve SVR12. This patient was excluded from the mFAS analysis.

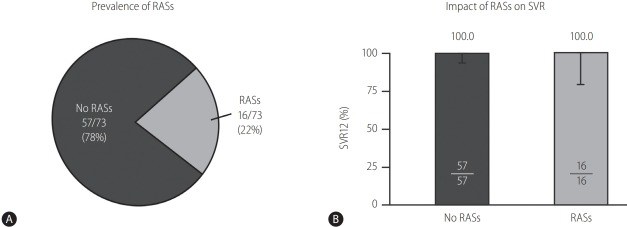

SVR12 rates were uniformly high across all subgroups of Korean patients receiving EBR/GZR for 12 weeks (Fig. 2). Notably, SVR12 was achieved by all patients with cirrhosis (25/25) and all those aged ≥65 years (16/16).

Figure 2.

SVR12 in select subgroups (FAS). Virologic outcome according to subgroups in full analysis set. SVR12, sustained virologic response at 12 weeks after completion of therapy; CI, confidence interval; FAS, full analysis set.

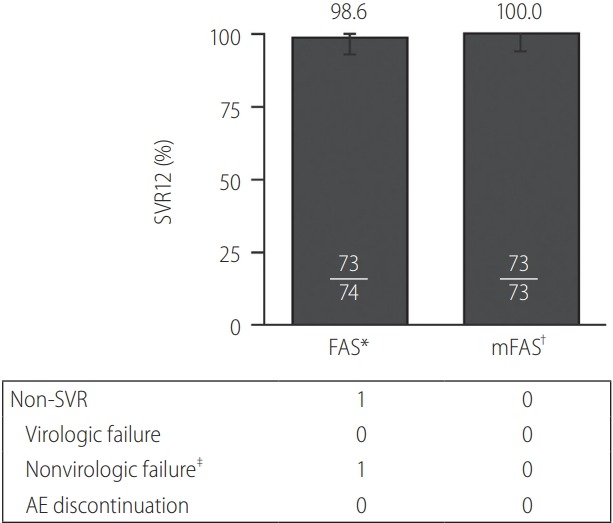

One patient, who withdrew consent, was excluded from the resistance analysis population owing to lack of virologic response data. Seventy-three patients were therefore assessed for the impact of baseline NS5A RASs at amino acid positions 28, 30, 31, or 93 on SVR12 rates. A total of 16 patients had RASs present at baseline (16/73, 22%), all of whom achieved SVR12 (Fig. 3). The remaining 57 patients with no NS5A RASs at baseline also achieved SVR12.

Figure 3.

Prevalence and impact of baseline NS5A RASs (mFAS). Prevalence of RAS (A), Impact on virologic outcome (B). mFAS, modified full analysis set; NS5A, nonstructural protein 5A; RAS, resistance-associated substitution; SVR12, sustained virologic response (SVR) at 12 weeks after completion of therapy. Next-generation sequencing with an ~25% or ~15% cutoff at amino acid position 28, 30, 31, or 93. Resistance-analysis population includes patients with available sequence data and excludes one patient who withdrew consent and did not complete the study.

Safety

Adverse events (AEs) were reported by 32/74 (43.2%) of Koreans receiving EBR/GZR for 12 weeks (Table 2). AEs reported in >5% of Korean patients were fatigue (n=5, 6.8%), upper respiratory tract infection (n=4, 5.4%), headache (n=4, 5.4%), and nausea (n=4, 5.4%). Thirteen patients (17.6%) reported drug-related AEs and two serious AEs occurred, neither of which was considered drug-related (suicide; multiple fractures).

Table 2.

Safety and tolerability of elbasvir/grazoprevir (EBR/GZR) administered for 12 weeks

| Korean patients (n=74) | |

|---|---|

| Any AEs | 32 (43.2) |

| Fatigue* | 5 (6.8) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection* | 4 (5.4) |

| Headache* | 4 (5.4) |

| Nausea* | 4 (5.4) |

| Drug-related AEs | 13 (17.6) |

| Serious AEs | 2 (2.7) |

| Drug-related serious AEs | 0 (0) |

| Discontinuation owing to AEs | 2† (2.7) |

| Death | 1‡ (1.4) |

Values are presented as n (%).

AEs, adverse events.

AEs listed occurred at a frequency ≥5%.

Two patients discontinued treatment owing to AEs: one had increased transaminase and bilirubin levels following ingestion of two bottles of Soju; the second had elevated alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase (ALT/AST) and eosinophil levels at treatment week 10 that met the protocol criteria for discontinuation. Both patients achieved sustained virologic response.

One patient withdrew consent and then committed suicide.

Two patients discontinued treatment. A 52-year-old man with cirrhosis had increased transaminase and bilirubin levels at treatment week 6 following ingestion of two bottles of the alcoholic beverage Soju the previous day. This patient met the protocolspecified discontinuation criteria of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >3× nadir and concomitant bilirubin increase >2× upper limit of normal and per protocol was discontinued on day 57 of treatment [13]. The second patient who discontinued treatment had elevated ALT/AST levels at treatment week 10 (ALT, 668 U/L; AST, 459 U/L) that were considered drug-related and met the protocol criteria for discontinuation [8]. Both patients achieved SVR. Narratives for these patients have been reported previously [8,13].

One death occurred in the study population. A 49-year-old woman without cirrhosis who was enrolled in the C-CORAL study committed suicide on day 57 of the study after withdrawing consent. This patient had no known history of depression or psychiatric illness and had reported suicidal ideation started 11 days prior to the event and refused further psychiatric consultation.

DISCUSSION

Data from this analysis extend the clinical profile for EBR/GZR. High rates of SVR12 were achieved in Korean patients with HCV GT1b infection receiving EBR/GZR for 12 weeks. There were no virologic failures among the treated population (either on-treatment failure or relapse), and only one patient, who withdrew consent, failed to achieve SVR12. Thus, among patients in the mFAS analysis, which excluded the patient who withdrew consent, SVR12 was achieved by 100% (73/73) of patients. The safety profile of EBR/GZR in this study was consistent with previous reports in Asian and Western patients [16], in which there were no drug-related serious AEs and with two patients who discontinued treatment, one was due to a drug-related ALT/AST elevation.

The result of the present analysis compare favorably with previous reports of treatment options available for Korean patients with HCV GT1b infection. Two studies indicate that SVR rates of 88–90% are achievable in Korean individuals with HCV GT1b infection receiving daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for 24 weeks [17,18]. In one of these studies, on-treatment virologic failures occurred in 7 of 76 treated patients, yielding an end-of-treatment response rate of 91% (69/76) [18]. In a single-arm phase 3b study, SVR12 was achieved by 99% (92/93) of Korean patients with HCV GT1 infection receiving sofosbuvir/ledipasvir for 12 weeks, the majority of whom had GT1b infection [19]. In this study, there were no on-treatment virologic failures and one relapsed patient who had the Y93 polymorphism present at baseline and time of failure.

A large integrated analysis of 1,070 patients with HCV GT1b infection has shown that EBR/GZR for 12 weeks is a safe and effective treatment option regardless of patient demographics or disease characteristics [20]. Overall, SVR12 was achieved by 97.2% (1,040/1,070) of patients and remained high in those with cirrhosis (188/189, 99.5%), HCV/HIV coinfection (51/54, 94.4%), and baseline viral load >800,000 IU/mL (705/728, 96.8%). In this integrated population, 21.6% of patients had baseline RASs at amino acid positions 28, 30, 31, or 93. SVR12 was achieved by 99.6% (820/823) of those with no baseline RASs and 94.7% (215/227) of those with baseline RASs (including an SVR12 rate of 95.2% [99/104] in patients with Y93 polymorphisms) [20]. In the present analysis, all 16 Korean patients with baseline NS5A RASs achieved SVR12. Combined, these data are consistent with the approved use of EBR/GZR, in which testing for baseline RAS is not required prior to the treatment of people with GT1b infection [15].

The C-CORAL study examined the safety and efficacy of EBR/ GZR for 12 weeks in individuals with HCV GT1, GT4, or GT6 infection from Russia and countries across the Asia Pacific region [21]. Approximately 80% of patients enrolled in this study had HCV GT1b infection. Rates of SVR were high in patients from China (146/151, 97%), South Korea (48/50, 96%), Taiwan (83/85, 98%), Russia (117/118, 99%), and Australia (26/28, 93%) but were lower in Vietnam (27/33, 82%) and Thailand (12/21, 57%) owing primarily to the high rate of virologic failure among patients with HCV GT6 infection in these countries [21]. Analysis of the EBR/GZR clinical trial database has also revealed similarly high rates of SVR12 in patients recruited outside of Korea. Compared with SVR12 rates in the present analysis, 97.4% (378/388) of non-Korean Asian patients and 96.9% (589/608) of non-Asian patients in the database achieved SVR12. The high SVR rates described in Korean patients in the current analysis are therefore consistent with SVR rates reported in individuals with HCV GT1b infection from other countries receiving EBR/GZR for 12 weeks.

Although controversial, it has been hypothesized that initiation of DAA therapy for the treatment of HCV infection may result in de novo or recurrent HCC [22]. A recent long-term extension study enrolling patients from the EBR/GZR clinical development program (including but not restricted to the Korean patients described in this analysis) reported that 15 of 2,435 patients developed HCC following GZR-based therapy, resulting in an HCC incidence rate of 2.77 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI, 1.55–4.56) [23]. This rate is similar to or lower than previously reported rates, suggesting no correlation between GZR-containing regimens and HCC incidence [24-29].

This analysis had several limitations. Most patients in this study were treatment-naive and HCV mono-infected; caution when extrapolating these findings to other patients groups, such as those previously treated for HCV infection or those with HCV/HIV coinfection. Korean patients in this analysis were identified as individuals enrolled at Korean study sites: no additional measures were taken to confirm the nationality/race of patients. The comparison of SVR12 rates between Korean, Asian, and non-Asian patients was restricted to individuals with HCV GT1b infection who received EBR/GZR for 12 weeks; however, these populations may have differed with regard to other characteristics, such as the proportions with cirrhosis, HIV coinfection, high baseline viral load, or other comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease, inherited blood disorders, or active injection drug use.

In conclusion, EBR/GZR administered for 12 weeks was well-tolerated and highly effective in Korean patients with HCV GT1b infection. All patients who completed treatment achieved SVR, including all 16 with NS5A RASs at baseline. EBR/GZR represents an effective treatment option for Korean individuals with HCV GT1b infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants, their families, and the investigators involved in these studies. Medical writing assistance was provided by Tim Ibbotson, PhD, of ApotheCom (Yardley, PA, USA). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Abbreviations

- AEs

adverse events

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- DAA

direct-acting antiviral

- EBR

elbasvir

- FAS

full analysis set

- GT

genotype

- GZR

grazoprevir

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- mFAS

modified FAS

- NS5A

nonstructural protein 5A

- RAS

resistance-associated set

- SVR

sustained virologic response

- SVR12

sustained virologic response at 12 weeks after completion of therapy

Study Highlights

• This is the first analysis of elbasvir/grazoprevir in Korean patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

• All patients who completed 12 weeks of treatment achieved a sustained virologic response.

• The safety profile of elbasvir/grazoprevir was consistent with that from previous reports in Asian and Western patients.

• Elbasvir/grazoprevir administered for 12 weeks was well-tolerated and highly effective in Korean patients with HCV genotype 1b infection.

Author contributions

Y.J. Lee, W.J. Chung, and B. Haber contributed to the acquisition of the data, interpretation of the results, and critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. J. Heo contributed to the conception, design, and planning of the study, acquisition of the data, interpretation of the results, and critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. D.Y. Kim and Y.J. Kim contributed to the acquisition of the data and to the critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. W.Y. Tak contributed to the acquisition of the data and the critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. S.W. Paik contributed to the conception, design, and planning of the study, acquisition and analysis of the data, interpretation of the results, drafting of the manuscript, and critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. E. Sim contributed to the conception, design, and planning of the study, interpretation of the results, and critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. S. Kulasingam contributed to the conception, design, and planning of the study and critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. R. Talwani contributed to the conception, design, and planning of the study, acquisition and analysis of the data, interpretation of the results, and critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. P. Hwang contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data and the critical review and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

All authors approved the final version of manuscript.

Funding support

Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Conflict of Interest

Y.J. Lee, J. Heo, D.Y. Kim, W.J. Chung, Y.J. Kim, and S.W. Paik have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

W.Y. Tak has received personal fees from Bayer HealthCare, Gilead Science Korea, AbbVie, Ono Pharma Korea, Eisai Korea, Bukwang Pharmaceutical, MSD, Korea, Yuhan, and Samil Pharmaceutical.

E. Sim, S. Kulasingam, B. Haber, and P. Hwang are current employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA (MSD) and may hold stock in Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

R. Talwani is a former employee of MSD and holds stock in Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:161–176. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim DY, Kim IH, Jeong SH, Cho YK, Lee JH, Jin YJ, et al. A nationwide seroepidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in South Korea. Liver Int. 2013;33:586–594. doi: 10.1111/liv.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim BK, Jang ES, Kim JH, Park SY, Ahn SV, Kim HJ, et al. Current status of and strategies for hepatitis C control in South Korea. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23:212–218. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2017.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeon JE. Recent update of the 2017 Korean Association for the Study of the Liver (KASL) treatment guidelines of chronic hepatitis C: comparison of guidelines from other continents, 2017 AASLD/IDSA and 2016 EASL. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24:278–293. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2018.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Summa V, Ludmerer SW, McCauley JA, Fandozzi C, Burlein C, Claudio G, et al. MK-5172, a selective inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3/4a protease with broad activity across genotypes and resistant variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4161–4167. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00324-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper S, McCauley JA, Rudd MT, Ferrara M, DiFilippo M, Crescenzi B, et al. Discovery of MK-5172, a macrocyclic hepatitis C virus NS3/4a protease inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:332–336. doi: 10.1021/ml300017p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coburn CA, Meinke PT, Chang W, Fandozzi CM, Graham DJ, Hu B, et al. Discovery of MK-8742: an HCV NS5A inhibitor with broad genotype activity. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:1930–1940. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeuzem S, Ghalib R, Reddy KR, Pockros PJ, Ben Ari Z, Zhao Y, et al. Grazoprevir-elbasvir combination therapy for treatment-naive cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1, 4, or 6 infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:1–13. doi: 10.7326/M15-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwo P, Gane E, Peng CY, Pearlman B, Vierling JM, Serfaty L, et al. Effectiveness of elbasvir and grazoprevir combination, with or without ribavirin, for treatment-experienced patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:164–175. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.045. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobson IM, Lawitz E, Kwo PY, Hézode C, Peng CY, Howe AYM, et al. Safety and efficacy of elbasvir/grazoprevir in patients with hepatitis C virus infection and compensated cirrhosis: an integrated analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1372–1382. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.050. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth D, Nelson DR, Bruchfeld A, Liapakis A, Sliva M, Monsour H, Jr, et al. Grazoprevir plus elbasvir in treatment-naive and treatmentexperienced patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease (the C-SURFER study): a combination phase 3 study. Lancet. 2015;386:1537–1545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rockstroh JK, Nelson M, Katlama C, Lalezari J, Mallolas J, Bloch M, et al. Efficacy and safety of grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK8742) in patients with hepatitis C virus and HIV co-infection (C-EDGE CO-INFECTION): a non-randomised, open-label trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2:e319–e327. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George J, Burnevich E, Sheen IS, Heo J, Kinh NV, Tanwandee T, et al. Elbasvir/grazoprevir in Asia-Pacific/Russian participants with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1, 4, or 6 infection. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2:595–606. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su F, Green PK, Berry K, Ioannou GN. The association between race/ ethnicity and the effectiveness of direct antiviral agents for hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2017;65:426–438. doi: 10.1002/hep.28901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zepatier . Prescribing information. Kenilworth, NJ: Merck & Co. Inc; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dusheiko GM, Manns MP, Vierling JM, Reddy KR, Sulkowski MS, Kwo PY, et al. Safety and tolerability of grazoprevir/elbasvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection: integrated analysis of phase 2-3 trials: 712 [Abstract] Hepatology. 2015;62:562A. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nam HC, Lee HL, Yang H, Song MJ. Efficacy and safety of daclatasvir and asunaprevir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22:259–266. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2016.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho BW, Kim SB, Song IH, Lee SH, Kim HS, Lee TH, et al. Efficacy and safety of daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for Korean patients with HCV genotype Ib infection: a retrospective multi-institutional study. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23:51–56. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2016.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim YS, Ahn SH, Lee KS, Paik SW, Lee YJ, Jeong SH, et al. A phase IIIb study of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir fixed-dose combination tablet in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced Korean patients chronically infected with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:947–955. doi: 10.1007/s12072-016-9726-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeuzem S, Serfaty L, Vierling J, Cheng W, George J, Sperl J, et al. The safety and efficacy of elbasvir and grazoprevir in participants with hepatitis C virus genotype 1b infection. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:679–688. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei L, Jia JD, Wang FS, Niu JQ, Zhao XM, Mu S, et al. Efficacy and safety of elbasvir/grazoprevir in participants with hepatitis C virus genotype 1, 4, or 6 infection from the Asia-Pacific region and Russia: final results from the randomized C-CORAL study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:12–21. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reig M, Mariño Z, Perelló C, Iñarrairaegui M, Riberiro A, Lens S, et al. Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol. 2016;65:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearlman BL, Lawitz EJ, Asselah T, Ginanni J, Palcza J, Robertson MN, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with hepatitis C virus infection following treatment with a grazoprevir-containing regimen [Abstract] Hepatology. 2018;68(1 Suppl):387A. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nahon P, Layese R, Bourcier V, Cagnot C, Marcellin P, Guyader D, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma after direct antiviral therapy for HCV in patients with cirrhosis included in surveillance programs. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1436–1450. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.015. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waziry R, Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Amin J, Law M, Danta M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk following direct-acting antiviral HCV therapy: a systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regression. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1204–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calvaruso V, Cabibbo G, Cacciola I, Petta S, Madonia S, Bellia A, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HCVassociated cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:411–421. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.008. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llovet JM, Villanueva A. Liver cancer: effect of HCV clearance with direct-acting antiviral agents on HCC. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:561–562. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conti F, Buonfiglioli F, Scuteri A, Crespi C, Bolondi L, Caraceni P, et al. Early occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol. 2016;65:727–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, Chayanupatkul M, Cao Y, El-Serag HB. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with directacting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:996–1005. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.012. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]