Abstract

Introduction

A new third version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ III) has been developed in response to trends in working life, theoretical concepts, and international experience. A key component of the COPSOQ III is a defined set of mandatory core items to be included in national short, middle, and long versions of the questionnaire. The aim of the present article is to present and test the reliability of the new international middle version of the COPSOQ III.

Methods

The questionnaire was tested among 23,361 employees during 2016–2017 in Canada, Spain, France, Germany, Sweden, and Turkey. A total of 26 dimensions (measured through scales or single items) of the middle version and two from the long version were tested. Psychometric properties of the dimensions were assessed regarding reliability (Cronbach α), ceiling and floor effects (fractions with extreme answers), and distinctiveness (correlations with other dimensions).

Results

Most international middle dimensions had satisfactory reliability in most countries, though some ceiling and floor effects were present. Dimensions with missing values were rare. Most dimensions had low to medium intercorrelations.

Conclusions

The COPSOQ III offers reliable and distinct measures of a wide range of psychosocial dimensions of modern working life in different countries; although a few measures could be improved. Future testing should focus on validation of the COPSOQ items and dimensions using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Such investigations would enhance the basis for recommendations using the COPSOQ III.

Keywords: Psychosocial risk factors, Psychosocial working conditions, Risk assessment

1. Introduction

The objective of this article is to present and test the reliability of the third international middle version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ III). This third version has been developed by the International COPSOQ Network reflecting its' increased international use [1]––the previous two versions were developed by the Danish National Research Centre of the Working Environment [2,3].

1.1. What is the COPSOQ?

The COPSOQ was originally developed for use in two settings: (1) occupational risk assessment and (2) research on work and health [[2], [3], [4]]. The COPSOQ instrument covers a broad range of domains including Demands at Work, Work Organization and Job Contents, Interpersonal Relations and Leadership, Work–Individual Interface, Social Capital, Offensive Behaviors, Health and Well-being. Previous versions of the COPSOQ were developed through factor analyses of a large range of items, and reliability of resulting scales was subsequently tested.

In the workplace setting, practitioners have an interest in measuring a broad range of psychosocial factors, both at the workplace level and for national monitoring [5,6]. In the research setting, it is likewise of interest to have broad coverage of psychosocial dimensions. This broad coverage also includes central elements of concepts widely used in research of work and health such as the demand control and the effort–reward imbalance (ERI) models [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11]], as well as other psychosocial factors such as emotional demands and quality of leadership [6,[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]].

The COPSOQ I and II came in short, middle, and long versions [3]. Originally, the short and medium versions were intended to be used in practical settings and the long version in research settings. Later, it turned out that also in research there was a need for shorter versions and that the middle version had sufficient reliability [3]. The COPSOQ has been recognized as a useful instrument by several organizations [16,17].

Previous to the development of the COPSOQ III, the instrument had been translated into 18 different languages and was used in 40 countries worldwide [3,[18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]]. The COPSOQ is also widely used in research, being applied in more than 400 peer-reviewed articles [37]. Finally, the COPSOQ has been applied to a variety of occupations and workplaces and has proven to be valid for national, as well as international comparisons [[38], [39], [40], [41], [42]].

1.2. Reasons for development of the COPSOQ III

The push to redevelop the COPSOQ II to a third version (COPSOQ III) was based on three reasons:

-

1)

Trends in the work environment: Work and working conditions have changed because of increased globalization and computerization to some extent intensified by the economic crisis in 2008. For example, types of management characterized by less trust (e.g., New Public Management; appraisal systems) have become more prevalent [43], along with the deterioration of working conditions in some [44,45], but not all countries [46,47]. Furthermore, income inequality has increased [48,49], and precarious work (e.g., involuntary part time work and short term contracts) has become more widespread [40,50,51], along with flexible timetables (e.g., weekend work, shift work), long working hours and lack of schedule adaptation. In addition, company restructurings and layoffs have led to less stable employment [43,49,51,52]. In recent decades technological change has been characterized by increased digitalization of work life [53]. This implicates new ways of interacting not only with coworkers but also with customers, patients, clients, or pupils (e.g., in telemedicine, robotics. and by means of communication technologies like email and social media) [[54], [55], [56]].

-

2)

Concepts: First, the Job demands-resources model (JD-R) through integration of classical work environmental models and job satisfaction research pointed at the need for a more comprehensive perspective than previous occupational health models [57,58]. This applies not merely to job demands and resources but also to a broader range of nontraditional health-related outcomes such as productivity and staff turnover. A wider focus regarding outcomes can facilitate integration of the perspective of occupational health and perspectives such as human resource management. In addition, there is an increasing awareness regarding trust, justice, reciprocity, and cohesion at the workplace pointing at the notion of social capital [13,[59], [60], [61]]. Another development is that new theories about stress in the workplace have evolved, such as the Stress-as-Offence-to-Self theory (SOS) [62]. This theory posits that how employees conceive they are treated by the management, through what tasks they are meant to do, and the circumstances under which they are to carry out tasks can be a source of stress [62]. In particular, when tasks and circumstances are laid out in a way that hinders the workers carrying out their work, this can be experienced as maltreatment and result in greater stress.

While these three topics (JD-R, social capital, and SOS) were already partly covered by earlier versions of the COPSOQ, the evolution of these theories in the last two decades necessitated greater coverage of these theories in the updated COPSOQ III.

-

3)

International experience with the COPSOQ: The questionnaire is being used in an increasing number of countries [1], which are very different regarding work and working conditions [40,[63], [64], [65]]. This development has led, on the one hand, to an increased need for adaptations to different national, cultural, and occupational contexts, and on the other hand, to suggestions for revision of existing items. For example, the international use of the COPSOQ has raised issues regarding wording of items (i.e. do items measure what they should), translation issues (e.g., between the Danish and English versions of the COPSOQ I and II) and differential item functioning (DIF) and differential item effects (DIEs). These experiences have also led to more knowledge on what dimensions are regarded as important on the shop floor level and what dimensions are most strongly associated with health.

1.3. The development process

In dealing with the aforementioned three reasons for further developing the questionnaire (societal trends, scientific concepts, and experience with the questionnaire), two strategic objectives were important. These were to update the instrument and, at the same time, allow comparability between populations and time periods. A test version was developed in a conceptual-guided consensus process to evaluate all items of versions I and II of the questionnaire according to their relevance for research and practice (Appendix Table 1). International Network members from Asia, the Americas and Europe were invited to assess items and dimensions of these versions. They were encouraged to comment and suggest changes on the network's regular biennial workshop meetings 2013-2017 in Ghent, Paris, and Santiago de Chile and in three online rounds of evaluations 2013-2016. In addition, psychometrics findings from research [36,66], results of Swedish cognitive interviews [20,61], reanalyzes of the existing COPSOQ I and II data by network members, and practical experiences were considered. Based on this process, a test version was finalized in spring 2016 and made available for further testing among network members.

1.4. What is new?

A number of changes were made in the third revised version of the COPSOQ (Table 1). These changes cover both the dimensions and the items of the questionnaire (Table 1). In addition, each dimension was defined in a few sentences to give reasons for the choice of items and improve the use of the questionnaire in general (Appendix Table 2). We have also further developed international guidelines regarding the use of the COPSOQ in practical settings [67].

Table 1.

Changes of the COPSOQ III as compared with the COPSOQ II

| Domain | Dimension | Change | Reason∗ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demands at Work | Emotional Demands | Item emotionally involved (ED4) was given up as it could be seen as describing commitment. In the same scale the item Deal with other people's problems (EDX2) replaced a previous item (ED2) as the new wording with better reflected the original Danish item. | Experience |

| Demands for Hiding Emotions | Dimension from the COPSOQ I was reintroduced. It was an important issue in shop floor measurements in, e.g., Belgium and Germany [36,68]. | Experience. | |

| Work Organization and Job Contents | Influence at Work | The item influence decisions concerning work (INX1) has replaced a previous item (IN1) as the new wording better reflected the original Danish item. In the same scale, two COPSOQ I items how quickly and how you do work (IN5 and IN6) were reintroduced as they better distinguish between those with low influence (unpublished analyses). | Experience |

| Possibilities for Development | The item take initiative (PD1) was given up as it performed poorly in the scale [66]; In addition, differential item effects (DIE) were found in analyses predicting self-rated health (unpublished analyses). | Experience | |

| Control over Working Time | Dimension from COPSOQ I was reintroduced to better assess aspects of work life conflict and was relabeled. Formerly labeled Degrees of freedom. Control over Working Time was an important issue in shop floor measurements in. e.g., Belgium and Germany and also found to be associated to well-being and health [36,68]. | Trends | |

| Interpersonal Relations and Leadership | Recognition | Dimension was relabeled from Rewards to better reflect the content of the items included. Items not strictly measuring this relabeled dimension were dropped: salary (RE4) and prospects (RE5). The first item is partly covered by a new Job Satisfaction item on salary (JS5), the latter partly by a Job Satisfaction item on prospects (JS1). | Experience |

| Role Conflicts | Items not strictly measuring this dimension were dropped: mixed acceptance (CO1) and unnecessary tasks (CO4).The last of these items was transferred into a new dimension ‘illegitimate tasks’ (IT1). | Experience | |

| Illegitimate Tasks | New dimension. Item taken from the COPSOQ II role conflicts scale. Inspiration from the theory of stress as a threat to self [62]. | Concepts | |

| Quality of Leadership | The item development opportunities (QLX1) replaces a former item (QL1), where the new item does refer more generally to the whole staff and not to each individual | Experience | |

| Social Support from Colleagues | The two items Support colleagues (SCX1) and Colleagues listen to problems (SCX2) replace former items (SC1, SC2) now stressing that people should report their level of support when they needed support. Formerly it was not possible to distinguish between low support and no need for support. | Experience | |

| Social Support from Supervisor | The two items Support supervisor (SS1) and Supervisor listens to problems (SSX2) replace the former items (SS1, SS2) now stressing that people should report their level of support when they needed support. Formerly it was not possible to distinguish between low support and no need for support. In addition, the revised third item in this scale Supervisor talks about performance (SSX3) also now refers to “immediate” supervisor replacing a former item (COPSOQ II: SS3). | Experience | |

| Sense of Community at Work | Dimension was relabeled. Formerly labeled as Social Community at Work. | Experience | |

| Work–Individual Interface | Commitment to the Workplace | The item recommend other people (CWX3) replaced a COPSOQ II item recommend a friend (CW3) as friend is a much more limited category than people. | Experience |

| Work Engagement | New dimension was introduced to cover the Job demands resource (JD-R) model better [57,58]. | Concepts | |

| Job Insecurity | The former Job Insecurity scale was split into this dimension and the dimension Insecurity over Working Conditions (Table 2). | Trends | |

| Insecurity over Working Conditions | The former Job Insecurity scale was split into this dimension and the dimension Job Insecurity (Table 2). | Trends | |

| Quality of Work | New dimension was introduced to cover the JD-R model better [57,58]. | Concepts | |

| Job Satisfaction | A new item on Salary (JS5) was introduced to better measure rewards [70,100]. | Experience | |

| Work Life Conflict | Dimension was relabeled to reflect various national contexts. Formerly labeled Work–family conflict. An item on being in two places was replaced with a similar item (WFX1) [21] and two new items were included (WF5 on interference and WF6 on changing plans) [18]. | Experience | |

| Social Capital | The domain has been relabeled so as to reflect what these dimensions are now called in practical and scientific settings [13,[59], [60], [61]]. In the COPSOQ II, the domain was called Values at the workplace level. | Concepts | |

| Vertical Trust | The dimension has been renamed from Trust regarding Management. The reason was that the new label has been used more often by network members. The item employees trust information (TMX2) has replaced a former item (TM2 in the COPSOQ II). The new item asks if “the employees” instead of formerly “you” can trust information from the management as this scale is operating on the workplace level and not on the individual level. | Experience | |

| Horizontal Trust | The dimension has been renamed from Mutual Trust between Employees. The reason was that the new label has been used more often by network members. | ||

| Organizational Justice | The dimension has been renamed from Justice. The reason was that the new label has been used more often by network members. | ||

| Social Inclusiveness | The scale was given up, as the questions on discrimination processes are difficult to assess in self reports. | Experience | |

| Offensive behaviors | Cyber Bullying | An item on Cyber Bullying (HSM) was introduced [20]. | Trends |

| Bullying | A new item on being unjustly criticized, bullied, and shown up was added [18,101]. | Experience | |

| Health and well-being | Self-rated Health | An item on self-rated health with other response options was added [18]. | Experience |

| Stress | The item on stress (ST4) was given up as it behaved differently from the rest of the items of the scale (differential item functioning; DIF); prevalence due to socioeconomic status deviated (unpublished analyses). The notion of stress has two meanings––both short-term healthy reaction and long-term unhealthy reaction––which makes this item difficult to interpret. | Experience |

1.4.1. The core item concept

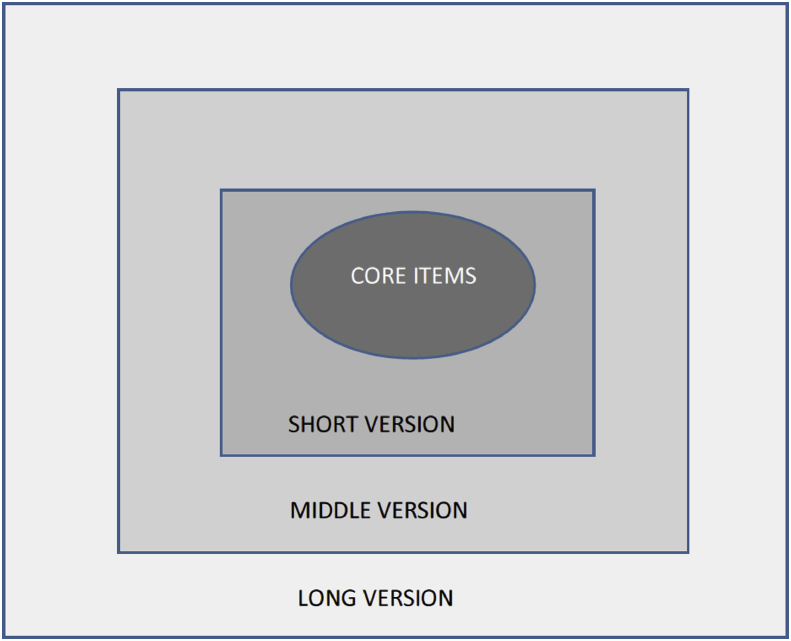

The concept of core items was introduced to ensure flexibility, and continuity, simultaneously. This concept guarantees comparability internationally, nationally, and over time. Core items were defined as mandatory in all national versions of the COPSOQ III, but they cannot stand alone. In other words, core items are to be supplemented by further items to establish short, middle, or long versions of the instrument (Fig. 1). In national versions, choice of supplementary items can deviate. Middle and short versions are developed as a basis for use in measurements in companies; long and middle versions are developed as a basis for use in research. National middle versions should consist of enough items to form reliable scales, thus consisting of two to four items (in the COPSOQ III, some middle dimensions only comprise one item, which is an issue we return to in the discussion). Short versions should consist of preferably two items. As a starting point, we have defined items for an international middle version of the COPSOQ III; as said, national versions can deviate. We did not suggest short version items, but national versions should consider middle items to supplement mandatory core items. This implicates a new standard for flexibility for establishing national versions of the COPSOQ.

Fig. 1.

The configuration of the COPSOQ III. For further explanation, refer to “The core item concept” in the Introduction.

1.4.2. Trends

To keep the COPSOQ updated to new trends, we changed the questionnaire dealing with the issues precariousness, work life conflict, and negative acts. Regarding precariousness, we introduced the new dimension Insecurity over Working Conditions [21], thus letting the scale Job Insecurity focus only on insecurity concerning employment. As previously mentioned, we reintroduced a dimension from the COPSOQ I, Control over Working Time, to cover aspects of work life conflict better. This dimension also correlated well with Health and Well-being [36,68]. We expanded and relabeled the Work Life Conflict dimension (before called Work–Family Conflict), and we modified and included new items for this scale. To cover aspects related to work life conflict better, we reintroduced a dimension from the COPSOQ I, then called Degrees of Freedom, now relabeled Control over Working Time. In addition, as negative acts also take place in the internet, we introduced the dimension Cyber Bullying [20].

1.4.3. Concepts

To be better able to integrate the field of occupational health with the field of management and organization addressed in the JD-R model [57,58] and in line with the rationale of positive occupational psychology, we added the dimensions Work Engagement [69] and Quality of Work to the questionnaire (Table 1). These dimensions complement the existing dimensions Meaning of Work, Job Satisfaction, and Commitment to the Workplace.

Furthermore, to better cover aspects often related to social capital [13,59,60], core items were defined for the scales on Sense of Community at Work and Social Support from Colleagues. This means that these dimensions are to be part of all national versions of the COPSOQ. In addition, the international middle version now includes Horizontal Trust, which before belonged to the long version (Table 1).

Finally, inspired by the SOS theory, we have now introduced the dimension Illegitimate Tasks [62].

1.4.4. Experience

The dimension Demands for Hiding Emotions was reintroduced from the COPSOQ I based on discussions with network members. This dimension also correlated well with Health and Well-being [36,68]. The dimension Social Inclusiveness was abandoned because of concerns about validity.

Several dimensions and items were also modified. Two items had translation issues between earlier Danish and English versions of the COPSOQ (Emotional Demands and Influence at Work); two items did not address the group level as intended (Quality of Leadership and Vertical Trust); four items were modified because of invalid wordings of questions not taking the need for support into account (Social Support from Supervisor and Colleagues, respectively); two other items were rephrased to increase clarity (Commitment to the Workplace and Social Support from Supervisor).

One item on satisfaction with salary was added to cover an aspect of the ERI model which was not included in the earlier COPSOQ versions (Job Satisfaction) [70]. Two items from the COPSOQ I were reintroduced as they better distinguished between those with low influence (Influence) (unpublished analyses); five items were introduced originating from national versions of the COPSOQ (Work Life Conflict, Bullying, Self-Rated Health); one of these items replaced an existing item (Work Life Conflict). Three items were dropped because of concerns regarding content validity (Emotional Demands, Possibilities for Development, and Stress); in the two latter cases, DIE [66] and DIF (unpublished analyses) were observed.

Three dimensions were relabeled. Now these dimensions are labeled as Vertical Trust, Horizontal Trust, and Organizational Justice; in the COPSOQ II, the corresponding labels were Trust regarding Management and Mutual Trust between Employees and Justice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Population

The questionnaire was tested in six countries in 2016 and 2017––in Canada, both French and English language versions were tested (Table 3). A total of 23,361 employees took part in the test. Some populations were national random samples (Canada, Spain, and France); some were company based (Germany, Sweden, and Turkey). In Germany, the company populations were heterogeneous across industries, the Swedish population was from private and public companies with an overweight of human service workers, and the Turkish population consisted of employees within the service sector and manufacturing. The Swedish and Canadian samples were dominated by occupations with high socioeconomic position, while the French and the German samples had an average occupational composition. In contrast, the occupational composition of the Turkish and especially the Spanish sample was skewed toward low socioeconomic positions.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study populations

| Country | Population | Collection method | N | Time period | Women, % | Age groups, % |

ISCO occupational group, % |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20 | 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60+ | Missing | 1-2 managers & professionals | 3-4 technicians, associate professionals, and clerical workers | 5-9 service, sales, agriculture trades, and manual workers | Missing | ||||||

| Canada, English | Canadians working in workplaces with more than 5 people | Electronic survey | 3,328 | 2016 | 48 | 1 | 11 | 18 | 25 | 30 | 15 | 1 | 42 | 34 | 21 | 3 |

| Canada, French | 885 | 2016 | 49 | 0 | 17 | 25 | 23 | 26 | 9 | 0 | 35 | 40 | 21 | 4 | ||

| Age groups, % |

||||||||||||||||

| <25 |

25-34 |

35-44 |

45-54 |

≥ 55 |

Missing |

|||||||||||

| Spain | Representative sample of salaried workers. | Household CAPI | 1,807 | 2016 | 51 | 8 | 19 | 29 | 29 | 14 | 0 | 12 | 19 | 70 | 0 | |

| France | Representative population of French employees | Electronic survey | 1,027 | 2017 | 48 | 5 | 31 | 23 | 28 | 14 | 0 | 12 | 55 | 33 | 0 | |

| Germany | Employees in organizations of different size and industry | Risk assessment surveys 60% online, 40 % paper | 13,011 | 2017 | 41 | 6 | 22 | 24 | 30 | 17 | 1 | 21 | 38 | 29 | 11 | |

| Sweden | Convenience sample from workplace surveys. 56% private, 44% public sector | Electronic surveys | 2,110 | 2016-17 | 68 | 3 | 24 | 25 | 23 | 19 | 6 | 72 | 16 | 8 | 4 | |

| Turkey | Company-based manufacturing industry samples from Aegean and Marmara regions, response rate 82.6% | Paper questionnaire | 1,076 | 2016-17 | 54 | 30 | 38 | 26 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 36 | 38 | 0 | |

| Total† | 23,361 | 2016-17 | 52 | 9* | 24* | 26* | 27* | 13* | 1* | 33 | 36 | 28 | 3 | |||

ISCO = International Classification of Occupations 2008, CAPI = Computer Assisted Personal Interview.

Except English and French Canada.

Total number of participants; mean proportion of women, age, and occupational groups where each population has the same weight.

Most populations had an average age between 40 and 45 years; the Canadian English population had an average age around 45 years; and the Turkish less than 35 years.

Most populations had an equal composition of men and women with two exceptions (Table 3). The German population consisted of 59% men (this is somewhat higher than the German average of 53%), and 68% of the Swedish population was women (reflecting the gender composition of the service sector in Sweden [71]).

In the national random samples, the participation rate ranged from 7.3% (Canada) to 70% (Spain), respectively. In the company-based samples, response rates were 59% (Germany), 82% (Sweden), and 83% (Turkey). The French sample was from internet polling survey, where a response rate could not be calculated.

The mode of data collection was internet survey in Canada, France, and Sweden and paper questionnaire in Turkey. Both these methods were used in Germany. In Spain, computer assisted personal interviews (CAPI) in the household were used.

The German data were weighted to reflect the composition of the German work force. No other data were weighted.

2.2. Variables

In the present article, the international middle version of the COPSOQ III was tested (Table 2). This international middle version consists of 60 items covering 26 dimensions (the COPSOQ III also comes in a long version consisting of 148 items covering 45 dimensions) [72]. In addition, two dimensions from the long version were tested (Commitment to the Workplace and Work Engagement; both belonging to the domain Work–Individual Interface). Four of the 27 tested international middle dimensions were on the domain Demands at Work (three of these including core items, Table 2), e.g., Quantitative Demands with three items, of which two were core items. Four dimensions were on the domain Work organization and Job Contents (three dimensions with core items), e.g., the dimension Influence at work with four items, of which one was core. Nine were on the domain Interpersonal Relations and Leadership (seven dimensions with core items), e.g., the dimension Predictability with two items, both core items. Five dimensions were on Work–Individual Interface (four dimensions with core items), e.g., the dimension Job Insecurity with two items, both being core. Three dimensions were on Social Capital (both dimensions had core items), e.g., the dimension Vertical Trust with three items, of which two were core, and one on General Health, namely Self-rated health consisting of one item, also being a core item. Of the 26 international middle version dimensions, 11 consisted of three to four items; 10 dimensions had two items. In five cases, the middle version dimensions were measured by one item (Recognition, Illegitimate Tasks, Quality of Work, Horizontal Trust, and Self-rated Health; the issue of only using on item is taken up in the beginning of the discussion section of the present article). The exact wordings of all items are available elsewhere [72]. All dimensions were measured with Likert Scale–type items and scaled to the interval 0-100 [72]. Each scale was scored in the direction indicated by the scale name [72].

Table 2.

Dimensions and items in the COPSOQ III. A short overview

| Domain | Dimension | Dimension name | II-long/middle/short | III-long | III-middle/core | Level | Item, item name. and short label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demands at Work | Quantitative Demands | QD | 4/4/2 | 4 | 3/2 | J | QD1 Work piles up¤; QD2 Complete task; QD3 Get behind∗; QD4 Enough time∗ |

| Work Pace | WP | 3/3/2 | 3 | 2/2 | J | WP1 Work fast∗; WP2 High pace∗; WP3 High pace necessary | |

| Cognitive Demands | DC | 4/0/0 | 4 | 0/0 | J | CD1 Eyes on lots of things; CD2 Remember a lot; CD 3 New ideas; CD4 Difficult decisions | |

| Emotional Demands | ED | 4/4/2 | 3 | 3/2 | J | ED1 Emotional disturbing¤; EDX2 Deal with other people's problems*; ED3 Emotionally demanding∗ | |

| Demands for Hiding Emotions | HE | 3/0/0 | 4 | 3/0 | JD | HE1 Treat equally; HE2 Hide feelings¤; HE3 Kind and open¤; HE4 Not state own opinion¤ | |

| Work Organization and Job Contents | Influence at Work | IN | 4/4/2 | 6 | 4/1 | J | INX1 Influence decisions on work*; IN2 Say in choosing colleges; IN3 Amount of work¤; IN4 Influence work task¤; IN5 Work Pace; IN6 How you work¤ |

| Possibilities for Development | PD | 4/4/2 | 3 | 3/2 | J | PD2 Learning new things∗; PD3 Use skills∗; PD4 Develop skills¤ | |

| Variation of Work | VA | 3/3/2 | 2 | 0/0 | J | VA1 Work varied; VA2 Do things over and over again | |

| Control over Working Time (1 | CT | — | 5 | 4/0 | JD | CT1 Decide breaks¤; CT2 Take holiday¤; CT3 Chat with colleague¤; CT4 Private business¤; (2 | |

| Meaning of Work | MW | 3/3/2 | 2 | 2/1 | J | MW1 Work meaningful∗; MW2 Work important¤ | |

| Interpersonal Relations and Leadership | Predictability | PR | 2/2/2 | 2 | 2/2 | D | PR1 Informed about changes∗; PR2 Information to work well∗ |

| Recognition (3 | RE | 3/3/2 | 3 | 1/1 | DC | RE1 Recognized by management∗; RE2 Respected by management; RE3 Treated fairly | |

| Role Clarity | CL | 3/3/2 | 3 | 3/1 | JD | CL1 Clear objectives∗; CL2 Responsibility¤; CL3 Expectation¤ | |

| Role Conflicts | CO | 4/4/0 | 2 | 2/2 | JD | CO2 Contradictory demands∗; CO3 Do things wrongly∗ | |

| Illegitimate Tasks | IT | — | 1 | 1/0 | JD | (4 | |

| Quality of Leadership | QL | 4/4/2 | 4 | 3/2 | D | QLX1 Development opportunities¤; QL2 Prioritize job satisfaction; QL3 Work planning∗; QL4 Solving conflicts∗ | |

| Social Support from Supervisor | SS | 3/3/2 | 3 | 2/1 | JD | SSX1 Supervisor listens to problems¤; SSX2 Support supervisor*; SSX3 Supervisor talks about performance | |

| Social Support from Colleagues | SC | 3/3/2 | 3 | 2/1 | JD | SCX1 Support colleagues*; SCX2 Colleagues listen to problems¤; SC3 Colleagues talk about performance | |

| Sense of Community at Work (5 | SW | 3/3/0 | 3 | 2/1 | JDC | SW1 Atmosphere∗; SW2 Cooperation; SW3 Community¤ | |

| Work–Individual Interface | Commitment to the Workplace | CW | 4/4/2 | 5 | 0/0 | IJC | CW1 Enjoy telling others; CW2 Workplace great importance; CWX3 Recommend to other people; CW4 Looking for work elsewhere; CW5 Proud |

| Work Engagement (6 | WE | — | 3 | 0/0 | IJC | WE1 Burst with energy; WE2 Enthusiastic; WE3 Immersed | |

| Job Insecurity (7 | JI | 4/0/0 | 3 | 2/2 | W | JI1 Unemployed∗; JI2 Redundant; JI3 Finding new job∗ | |

| Insecurity over Working Conditions (8 | IW | 5 | 3/1 | W | *(9; IW2 Transferred another task; IW3 Changed working time¤; IW4 Decreased salary¤; (10 | ||

| Quality of Work | QW | — | 2 | 1/0 | W | QW1 Possible to perform own tasks; QW2 Satisfied at workplace level¤ | |

| Job Satisfaction | JS | 4/4/1 | 5 | 3/1 | W | JS1 Work prospects¤; JS2 Work conditions; JS3 Work abilities; JS4 Job in general∗; JS5 Salary¤ | |

| Work Life Conflict (11 | WF | 4/4/2 | 6 | 2/2 | W | WFX1 Being in both places; WF2 Energy conflict∗; WF3 Time conflict∗; WF5 Work demands interfere; WF6 Change plans | |

| Social Capital (12 | Vertical Trust (13 | TM | 3/3/0 | 4 | 3/2 | C | TM1 Management trust employees∗; TM2 Employees trust information∗; TM3Management withhold information; TM4 Employees express views¤ |

| Horizontal Trust (14 | TE | 4/4/2 | 3 | 1/0 | C | TE1 Colleagues withhold information; TE2 Withhold information management; TE3 Trust colleagues¤ | |

| Organizational Justice (15 | JU | 4/4/2 | 4 | 2/2 | C | JU1 Conflicts resolved fairly∗; JU2 Employees appreciated; JU3 Suggestions treated seriously; JU4 Work distributed fairly∗ | |

| Conflicts and offensive behaviors | Gossip and Slander | GS | 1/0/0 | 1 | 0/0 | W | GS Gossip and slander |

| Conflicts and Quarrels | CQ | 1/0/0 | 1 | 0/0 | W | CQ1 Conflicts and quarrels | |

| Unpleasant Teasing | UT | 1/0/0 | 1 | 0/0 | W | UT1 Unpleasant teasing | |

| Cyber Bullying | HSM | — | 1 | 0/0 | JW | HSM1 Cyber bullying | |

| Sexual Harassment | SH | 1/1/1 | 1 | 0/0 | JW | SH1 Sexual harassment | |

| Threats of Violence | TV | 1/1/1 | 1 | 0/0 | JW | TV1 Threats of violence | |

| Physical Violence | PV | 1/1/1 | 1 | 0/0 | JW | PV1 Physical violence | |

| Bullying | BU | 1/1/1 | 2 | 0/0 | W | BU1 Bullying; BU2 Unjustly criticized, bullied, shown up | |

| Health and well-being | Self-rated Health | GH | 1/1/1 | 2 | 1/1 | I | GH1 General health∗; GH2 Rate in 10 points |

| Sleeping Troubles | SL | 4/4/0 | 4 | 0/0 | I | SL1 Slept badly; SL2 Hard to sleep; SL3 Woken up early; SL4 Woken up several times | |

| Burnout | BO | 4/4/2 | 4 | 0/0 | I | BO1 Worn out; BO2 Physically exhausted; BO3 Emotionally exhausted; BO4 Tired | |

| Stress | ST | 4/4/2 | 3 | 0/0 | I | ST1 Problems relaxing; ST2 Irritable; ST3 Tense | |

| Somatic Stress | SO | 4/0/0 | 4 | 0/0 | I | SO1 Stomach ache; SO2 Headache; SO3 Palpitations; SO4 Muscle tension | |

| Cognitive Stress | CS | 4/0/0 | 4 | 0/0 | I | CS1 Problems concentrating; CS2 Difficult thinking clearly; CS3 Difficult taking decisions; CS4 Difficult remembering | |

| Depressive Symptoms | DS | 4/0/0 | 4 | 0/0 | I | DS1 Sadness; DS2 Lack of self-confidence; DS3 Feel guilty; DS4 Lack of interest in daily activity | |

| Personality | Self-Efficacy | SE | 6/0/0 | 6 | 0/0 | I | SE1 Solve problems; SE2 Achieving what I want; SE3 Reach objectives; SE4 Handle unexpected events; SE5 Several ways solving problems; SE6 Usually manage |

Exact formulation of items is available [72]. Italic denotes new Dimension or Item. Bold and italic denote a relabeled Domain, Dimension or wording of Item. Underscore and italic denote Dimension or Item from the COPSOQ I. Underscore, bold and italic denote a relabeled Dimension from the COPSOQ I. Double underscore and italic denote Item transferred from another the COPSOQ II scale. Level: Individual level; J, Job level; D, Department level; C, Company level; W, Work–individual interface.

Note that core items are mandatory in all short, middle, and long national versions of the COPSOQ. Choice of items national middle versions can deviate from the international version listed here.

Explanation of footnotes in the table: (1 In COPSOQ I & II labeled Degrees of freedom. (2 From the COPSOQ I Quantitative Demands scale. (3 In COPSOQ II labeled Recognition (Reward). (4 From COPSOQ II Role Conflicts scale, item CO4. (5 In COPSOQ I & II labeled Social Community at Work. (6 From the Work Engagement scale [69]. (7 In COPSOQ I & II labeled Job Insecurity. (8 Split out from the Job Insecurity scale from COPSOQ I & II. (9 From the COPSOQ I & II Job Insecurity scale, item JI4. (10 From the test version of the COPSOQ II Rewards scale. (11 In COPSOQ II labeled Work–family conflict. (12 In COPSOQ 2 called Values on the workplace level (13 In COPSOQ II labeled Trust regarding management. (14 In COPSOQ II labeled Mutual trust between employees. (15 In COPSOQ II labeled Justice.

Mandatory core item; ¤middle item; otherwise long item.

The original English COPSOQ III wording was used without modifications as the Canadian English version. In all other versions, the new COPSOQ III items were established by translation–back translation from the English version. The Canadian French version took also the existing French COPSOQ translation and conducted field tests with translators. A translation–back translation procedure was performed when there was disagreement between translators.

In Turkey, the existing COPSOQ I and II questions were translated using translation–back translation based on the English version; the German and Swedish versions were based on both the Danish and English versions; the Spanish was based on the Danish version. Regarding the Canadian French version, translations were performed the same way as for the new COPSOQ III items, in addition, taking the existing Belgian version into account. The Swedish translation also took cognitive interview test results into account [20].

The international middle version was tested at least partly in all countries (Table 4).

Table 4.

Scale characteristics for international standard middle and selected long version∗ dimensions among 23,361 employees in Canada, Spain, France, Germany, Sweden, and Turkey in 2016-2017

| Domain | Dimension | Dimension name and country tested | No. of items | Scale mean | Observed range of scale means | Cronbach α | 95% CI of α | Observed range of α | Floor answers, % (range) | Ceiling answers, % (range) | Missing answers, % (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demands at Work | Quantitative Demands | QD ES, SE, TR | 3 | 39 | 23 – 51 | 0.77 | 0.71 - 0.82 | 0.72 - 0.82 | 12 (1 - 30) | 1 (0 - 2) | 1 (0 - 2) |

| Work Pace | WP CA, ES, FR, DE, SE, TR | 2 | 61 | 52 – 68 | 0.80 | 0.75 - 0.83 | 0.69 - 0.86 | 2 (0 - 8) | 9 (5 - 13) | 1 (0 - 2) | |

| Emotional Demands | ED CA, ES, FR, SE, TR | 3 | 47 | 37 – 58 | 0.80 | 0.78 - 0.82 | 0.76 - 0.83 | 7 (2 - 17) | 3 (1 - 5) | 0 (0 - 1) | |

| Demands for Hiding Emotions | HE ES, TR | 3 | 57 | 56 – 58 | 0.66 | 0.58 - 0.73 | 0.62 - 0.70 | 2 (1 - 2) | 6 (3 - 8) | 1 (0 - 2) | |

| Work Organization and Job Contents | Influence at Work | IN ES, TR | 4 | 42 | 38 – 45 | 0.80 | 0.73 - 0.86 | 0.77 - 0.83 | 8 (6 - 10) | 3 (1 - 5) | 1 (0 - 2) |

| Possibilities for Development | PD ES, SE, TR | 3 | 66 | 64 – 68 | 0.82 | 0.76 - 0.87 | 0.78 - 0.87 | 2 (1 - 3) | 14 (8 - 20) | 0 (0 - 1) | |

| Control over Working Time | CT ES, TR | 4 | 39 | 33 – 45 | 0.69 | 0.57 - 0.78 | 0.63 - 0.74 | 6 (6 - 7) | 3 (1 - 4) | 2 (0 - 4) | |

| Meaning of Work | MW CA, ES, FR, DE, SE, TR | 2 | 72 | 53 – 80 | 0.81 | 0.74 - 0.87 | 0.62 - 0.91 | 2 (1 - 4) | 25 (8 - 36) | 1 (0 - 2) | |

| Interpersonal Relations and Leadership | Predictability | PR CA, ES, FR, DE, SE, TR | 2 | 56 | 52 – 64 | 0.73 | 0.69 - 0.76 | 0.66 - 0.79 | 3 (2 - 6) | 6 (3 - 18) | 0 (0 - 1) |

| Recognition | RE CA, ES, FR, DE, SE, TR | 1 | 55 | 44 – 68 | † | † | † | 12 (6 - 24) | 14 (8 - 32) | 1 (0 - 2) | |

| Role Clarity | CL ES, DE, SE, TR | 3 | 75 | 71 – 81 | 0.82 | 0.79 - 0.85 | 0.79 - 0.86 | 0 (0 - 1) | 18 (7 - 38) | 1 (0 - 1) | |

| Role Conflicts | CO CA, FR, DE, SE, TR | 2 | 45 | 43 – 47 | 0.73 | 0.67 - 0.77 | 0.61 - 0.8 | 6 (2 - 10) | 3 (1 - 5) | 0 (0 - 1) | |

| Illegitimate Tasks | IT CA, ES, SE, TR | 1 | 43 | 30 – 48 | † | † | † | 18 (8 - 41) | 8 (6 - 12) | 0 (0 - 1) | |

| Quality of Leadership | QL ES, DE, SE, TR | 3 | 61 | 53 – 66 | 0.87 | 0.86 - 0.88 | 0.85 - 0.87 | 3 (2 - 5) | 10 (5 - 16) | 2 (1 - 3) | |

| Social Support from Colleagues | SC ES, FR, DE, SE, TR | 2 | 68 | 57 – 81 | 0.87 | 0.82 - 0.90 | 0.77 - 0.92 | 3 (2 – 4) | 25 (11 - 46) | 1 (0 - 2) | |

| Social Support from Supervisor | SS CA, ES, DE, SE, TR | 2 | 69 | 55 – 82 | 0.81 | 0.77 - 0.85 | 0.72 - 0.86 | 2 (0 - 4) | 21 (6 - 38) | 4 (0 - 16) | |

| Sense of Community at Work | SW ES, SE, TR | 2 | 77 | 74 – 82 | 0.79 | 0.66 - 0.88 | 0.7 - 0.88 | 1 (0 - 1) | 30 (29 - 32) | 6 (0 - 16) | |

| Work–Individual Interface | Commitment to the Workplace∗ | CW SE | 2 | 69 | 69 – 69 | 0.64 | 0.61 - 0.67 | 0.64 - 0.64 | 1 (1 - 1) | 13 (13 - 13) | 0 (0 - 0) |

| Work Engagement∗ | WE DE, SE | 3 | 67 | 63 – 70 | 0.85 | 0.84 - 0.86 | 0.85 - 0.86 | 0 (0 - 1) | 4 (3 - 4) | 1 (0 - 2) | |

| Job Insecurity | JI CA, ES, FR, DE, SE, TR | 2 | 39 | 12 – 54 | 0.72 | 0.69 –- 0.75 | 0.66 - 0.76 | 19 (4 - 42) | 7 (0 - 17) | 1 (0 - 2) | |

| Insecurity over Work. Cond. | IW ES, DE, TR | 3 | 41 | 30 – 52 | 0.76 | 0.72 - 0.79 | 0.73 - 0.79 | 13 (8 - 18) | 5 (2 - 8) | 1 (1 - 2) | |

| Quality of Work | QW ES, SE | 1 | 71 | 68 – 75 | † | † | † | 2 (1 - 3) | 26 (15 - 36) | 1 (1 - 1) | |

| Job Satisfaction | JS ES, TR | 3 | 56 | 53 – 60 | 0.80 | 0.76 - 0.83 | 0.78 - 0.81 | 2 (1 - 4) | 5 (3 - 6) | 1 (1 - 1) | |

| Work Life Conflict | WF CA, FR, DE, SE, TR | 2 | 42 | 35 – 51 | 0.84 | 0.80 - 0.87 | 0.78 - 0.88 | 15 (7 - 20) | 8 (2 - 18) | 0 (0 - 1) | |

| Social Capital | Vertical Trust | TM ES, SE, TR | 3 | 64 | 56 – 70 | 0.82 | 0.79 - 0.85 | 0.8 - 0.85 | 2 (1 - 3) | 9 (4 - 14) | 1 (1 - 1) |

| Horizontal Trust | TE ES, FR, SE, TR | 1 | 62 | 50 – 73 | † | † | † | 5 (1 - 11) | 15 (7 - 24) | 5 (0 - 17) | |

| Organizational Justice | JU CA, ES, FR, DE, SE, TR | 2 | 57 | 51 – 64 | 0.77 | 0.74 - 0.80 | 0.7 - 0.82 | 4 (2 - 7) | 6 (4 - 13) | 1 (0 - 2) | |

| Health and well-being | Self-rated Health | GH CA, ES, FR, SE | 1 | 63 | 60 – 66 | † | † | † | 2 (1 - 4) | 12 (7 - 16) | 1 (0 - 2) |

Values for scale means, Cronbach α, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of Cronbach α, and fractions with floor; ceiling; and missing answers were estimated as the overall mean of the 7 versions. Confidence intervals were calculated using a random effects model to account for heterogeneity [75]. Observed range of scale means and Cronbach α was lowest and highest values in each of the versions tested.

ES = Spain, SE = Sweden, TR = Turkey, CA = Canada, FR = France, DE = Germany.

The selected long version scales are Commitment to the Workplace and Work Engagement.

Single item dimension. Calculation of Cronbach α is not applicable.

2.3. Analyses

For each dimension in the international middle COPSOQ III, mean scale score and fractions with ceiling, floor, and missing values were calculated. For dimensions measured as multiitem scales, Cronbach α was calculated to assess reliability, an α ≥ 0.7 was deemed acceptable [2,3]. For each item in the scales, corrected item-total correlations were calculated; values => 0.4 were deemed acceptable [73,74]. Spearman scale intercorrelations were calculated where possible to evaluate divergent and convergent validity [2,3].

Properties of the international middle dimensions were summarized as estimated overall means of the seven versions, where each of the seven populations analyzed had the same weight; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of Cronbach α were estimated using a random effects model to account for heterogeneity of the results [75]. Lowest and highest values across populations were also identified.

3. Results

Summarized over all countries, most scales of the international middle version showed acceptable to good reliability, that is, Cronbach α more than 0.7 (Table 4). Most corrected item-total correlations had acceptable to good levels, i.e., more than 0.4 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Corrected item-total correlations of international middle and selected long version∗ dimensions

| Domain | Scale | Level | Item name | Item wording | Corrected item-total correlation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | |||||

| Demands at work | Quantitative Demands (QD) | Middle | QD1 | Is your workload unevenly distributed so it piles up? | 0.56 | 0.52 - 0.61 |

| Core | QD2 | How often do you not have time to complete all your work tasks? | 0.64 | 0.53 - 0.70 | ||

| Core | QD3 | Do you get behind with your work? | 0.66 | 0.57 - 0.76 | ||

| Work Pace (WP) | Core | WP1 | Do you have to work very fast? | 0.64 | 0.52 - 0.73 | |

| Core | WP2 | Do you work at a high pace throughout the day? | 0.64 | 0.52 - 0.73 | ||

| Emotional Demands (ED) | Middle | ED1 | Does your work put you in emotionally disturbing situations? | 0.68 | 0.65 - 0.72 | |

| Core | EDX2 | Do you have to deal with other people's personal problems as part of your work? | 0.59 | 0.49 - 0.65 | ||

| Core | ED3 | Is your work emotionally demanding? | 0.69 | 0.63 - 0.75 | ||

| Demands for Hiding Emotions (HE) | Middle | HE2 | Does your work require that you hide your feelings? | 0.54 | 0.43 - 0.64 | |

| Middle | HE3 | Are you required to be kind and open towards everyone – regardless of how they behave towards you? | 0.30 | 0.28 - 0.32 | ||

| Middle | HE4 | Does your work require that you do not state your opinion? | 0.50 | 0.34 - 0.66 | ||

| Work Organization and Job Contents | Influence at Work (I) | Core | INX1 | Do you have a large degree of influence on the decisions concerning your work? | 0.57 | 0.49 - 0.65 |

| Middle | IN3 | Can you influence the amount of work assigned to you? | 0.55 | 0.49 - 0.60 | ||

| Middle | IN4 | Do you have any influence on what you do at work? | 0.71 | 0.68 - 0.75 | ||

| Middle | IN6 | Do you have any influence on HOW you do your work? | 0.63 | 0.62 - 0.64 | ||

| Possibilities for Development (Skill discretion) (PD) | Core | PD2 | Do you have the possibility of learning new things through your work? | 0.67 | 0.59 - 0.71 | |

| Core | PD3 | Can you use your skills or expertise in your work? | 0.63 | 0.47 - 0.76 | ||

| Middle | PD4 | Does your work give you the opportunity to develop your skills? | 0.74 | 0.72 - 0.78 | ||

| Control over Working Time (CT) | Middle | CT1 | Can you decide when to take a break? | 0.53 | 0.49 - 0.57 | |

| Middle | CT2 | Can you take holidays more or less when you wish? | 0.43 | 0.38 - 0.48 | ||

| Middle | CT3 | Can you leave your work to have a chat with a colleague? | 0.55 | 0.54 - 0.56 | ||

| Middle | CT4 | If you have some private business is it possible for you to leave your place of work for half an hour without special permission? | 0.40 | 0.28 - 0.53 | ||

| Meaning of Work (MW) | Core | MW1 | Is your work meaningful? | 0.68 | 0.53 - 0.84 | |

| Middle | MW2 | Do you feel that the work you do is important? | 0.68 | 0.53 - 0.84 | ||

| Interpersonal Relations and Leadership | Predictability (PR) | Core | PR1 | At your place of work. are you informed well in advance concerning, for example important decisions. changes or plans for the future? | 0.58 | 0.50 - 0.66 |

| Core | PR2 | Do you receive all the information you need to do your work well? | 0.58 | 0.50 - 0.66 | ||

| Role Clarity (CL) | Core | CL1 | Does your work have clear objectives? | 0.63 | 0.57 - 0.71 | |

| Middle | CL2 | Do you know exactly which areas are your responsibility? | 0.70 | 0.64 - 0.77 | ||

| Middle | CL3 | Do you know exactly what is expected of you at work? | 0.69 | 0.62 - 0.76 | ||

| Role Conflicts (CO) | Core | CO2 | Are contradictory demands placed on you at work? | 0.56 | 0.45 - 0.66 | |

| Core | CO3 | Do you sometimes have to do things which ought to have been done in a different way? | 0.56 | 0.45 - 0.66 | ||

| Quality of Leadership (QL) | Middle | QLX1 | To what extent would you say that your immediate superior makes sure that the members of staff have good development opportunities? | 0.67 | 0.64 - 0.72 | |

| Core | QL3 | To what extent would you say that your immediate superior is good at work planning? | 0.77 | 0.76 - 0.79 | ||

| Core | QL4 | To what extent would you say that your immediate superior is good at solving conflicts? | 0.76 | 0.74 - 0.78 | ||

| Social Support from Supervisor (SS) | Middle | SSX1 | How often is your immediate superior willing to listen to your problems at work. if needed? | 0.73 | 0.56 - 0.85 | |

| Core | SSX2 | How often do you get help and support from your immediate superior. if needed? | 0.73 | 0.56 - 0.85 | ||

| Social Support from Colleagues (SC) | Core | SCX1 | How often do you get help and support from your colleagues. if needed? | 0.70 | 0.62 - 0.76 | |

| Middle | SCX2 | How often are your colleagues willing to listen to your problems at work. if needed? | 0.70 | 0.62 - 0.76 | ||

| Sense of Community at Work (SW) | Core | SW1 | Is there a good atmosphere between you and your colleagues? | 0.61 | 0.56 - 0.66 | |

| Middle | SW3 | Do you feel part of a community at your place of work? | 0.61 | 0.56 - 0.66 | ||

| Work–Individual Interface | Commitment to the Workplace (CW)∗ | Long | CWX3 | Would you recommend other people to apply for a position at your workplace? | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| Long | CW4 | How often do you consider looking for work elsewhere? | 0.63 | 0.63 | ||

| Work Engagement (WE)∗ | Long | WE1 | At my work. I feel bursting with energy | 0.68 | 0.64 - 0.72 | |

| Long | WE2 | I am enthusiastic about my job | 0.80 | 0.79 - 0.80 | ||

| Long | WE3 | I am immersed in my work | 0.70 | 0.65 –- 0.74 | ||

| Job Insecurity (JI) | Core | JI1 | Are you worried about becoming unemployed? | 0.57 | 0.50 - 0.62 | |

| Core | JI3 | Are you worried about it being difficult for you to find another job if you became unemployed? | 0.57 | 0.50 - 0.62 | ||

| Insecurity over Working Conditions (IW) | Core | IW1 | Are you worried about being transferred to another job against your will? | 0.58 | 0.55 - 0.61 | |

| Middle | IW3 | Are you worried about the timetable being changed (shift. weekdays. time to enter and leave …) against your will? | 0.58 | 0.53 - 0.65 | ||

| Middle | IW4 | Are you worried about a decrease in your salary (reduction. variable pay being introduced …)? | 0.54 | 0.51 - 0.63 | ||

| Job Satisfaction (JS) | Middle | JS1 | Regarding your work in general. How pleased are you with your work prospects? | 0.70 | 0.66 - 0.73 | |

| Core | JS4 | Regarding your work in general. How pleased are you with your job as a whole. everything taken into consideration? | 0.69 | 0.65 - 0.72 | ||

| Middle | JS5 | Regarding your work in general. How pleased are you with your salary? | 0.58 | 0.54 - 0.62 | ||

| Work Life Conflict (WF) | Core | WF2 | Do you feel that your work drains so much of your energy that it has a negative effect on your private life? | 0.75 | 0.64 - 0.81 | |

| Core | WF3 | Do you feel that your work takes so much of your time that it has a negative effect on your private life? | 0.75 | 0.64 - 0.81 | ||

| Social Capital | Vertical Trust (TM) | Core | TM1 | Does the management trust the employees to do their work well? | 0.69 | 0.65 - 0.74 |

| Core | TMX2 | Can the employees trust the information that comes from the management? | 0.71 | 0.69 - 0.74 | ||

| Middle | TM4 | Are the employees able to express their views and feelings? | 0.64 | 0.58 - 0.71 | ||

| Organizational Justice (JU) | Core | JU1 | Are conflicts resolved in a fair way? | 0.63 | 0.54 - 0.69 | |

| Core | JU4 | Is the work distributed fairly? | 0.63 | 0.54 - 0.69 | ||

Countries in which items have been tested are indicated in Table 4, 3rd column.

The selected long version scales are Commitment to the Workplace and Work Engagement.

Across populations, three of the 23 scales tested had a Cronbach α less than 0.7. These were Commitment to the Workplace (two items, mean α = 0.64; 95% CI: 0.61 – 0.67), Demands for Hiding Emotions (three items, mean α = 0.66; 95% CI: 0.58 – 0.73), and Control over Working Time (four items, mean α = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.57 – 0.78). The Demands for Hiding Emotions scale had an item with a corrected item-total correlation less than 0.4 (HE3: having to be kind and open to everyone; mean-corrected item-total correlation = 0.30).

Looking at the specific populations, some countries had scales with insufficient Cronbach α's, in addition to those previously mentioned. These were Predictability (two items; 0.62 in France and 0.66 in Turkey), Meaning of Work (two items; 0.62 in France), Job Insecurity (two items; 0.66 in France and 0.67 in Germany), and Work Pace (two items; 0.69 in Spain) (table not shown). Furthermore, in specific populations, some items––other than the item previously mentioned––had insufficient corrected item-total correlations: in Spain, one item belonging to the Demands on Hiding Emotions scale (HE4: requirements not stating opinion = 0.34), and two items in Turkey belonging to the Control over Working Time scale (CT2: holidays = 0.38; CT4 leave work for private business = 0.28) (Table 5).

The mean scores for the international middle dimensions ranged from 39 (Quantitative Demands) to 77 (Sense of Community at Work) (Table 4). For some dimensions, these means reflect large variations among the populations studied. The largest variations were found regarding Job Insecurity (from 12 in Sweden to 54 in Spain) and Work Life Conflict (where five countries reported values) (35 in Germany to 51 in Turkey). The smallest variation was found regarding Hiding Emotions (56 in Spain to 58 in Turkey). Note that these variations are partly due to variations in the number of countries that tested each scale (see Table 4, 3rd column). In some cases, floor and ceiling effects more than 15% were present. Floor effects were present for Illegitimate Tasks (18%) and Job Insecurity (19%). Ceiling effects were seen for Sense of Community at work (30%), Social Support from Colleagues and from Supervisor (21% and 25%, respectively) as well as Meaning of Work and Quality of Work (25% and 26%, respectively). In all cases, floor and ceiling effects reflected very high or low mean values of the dimensions.

Generally, there were low fractions of missing values (Table 4). In three scales, fractions of around 5% of missing values occurred. These were Social Support from Colleagues, Horizontal Trust, and Sense of Community at Work mainly corresponding to employees responding “I do not have colleagues”.

The intercorrelations of the international middle dimensions––including two selected long version dimensions––corroborate, on the one hand, that all psychosocial working environment dimensions were distinct from each other, and on the other hand, that dimensions within each domain were generally related with each other to a higher degree than with dimensions from other domains (Appendix Table 3.A, Appendix Table 3.B, Appendix Table 3.C). However, Commitment to the Workplace from the domain Work–Individual Interface was also correlated highly to some dimensions from the domains Work Organization and Job Contents, Interpersonal Relations and Leadership, and Social Capital. In addition, Vertical Trust and Organizational Justice from the domain Social Capital correlated highly with some dimensions from Interpersonal Relations and Leadership and Work–Individual Interface. Of 373 intercorrelations, only seven were more than 0.60 and none greater than 0.69 (the latter involving Organizational Justice and Vertical Trust). The highest mean intercorrelations regarded dimensions belonging to the domains Interpersonal Relations and Leadership (involving Recognition, Predictability, Social Support from Supervisor, and Quality of Leadership), Work–Individual Interface (involving Commitment to the Workplace and Job Satisfaction), and Social Capital (involving the dimensions Organizational Justice and Vertical Trust). Further details are presented in Appendix Table 3.A, Appendix Table 3.B, Appendix Table 3.C, upper right parts. We found the same general pattern in each of the populations studied (ranges in lower left parts of Appendix Table 3.A, Appendix Table 3.B, Appendix Table 3.C).

Sensitivity analyses show that the specific level of reliability and the level of intercorrelations to a large degree were influenced by the country.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present article was to analyze the reliability of the international middle version of the COPSOQ III. The analyses demonstrated that most international middle scales of the COPSOQ III have an acceptable to good internal consistency, as measured through Cronbach α, across a heterogeneous set of worker samples, from multiple countries. Few scales had floor and ceiling effects or high fractions of missing values. The correlation analysis indicates that dimensions are measuring different constructs as expected.

In a few cases, possible problems with internal consistency were indicated, which we do not believe are due to translation issues. Across the populations being studied, three scales had insufficient Cronbach α′s ranging from 0.64 to 0.69. The Commitment to the Workplace scale had only two items and could be extended with more items. The Hiding Emotions scale had three items, of which one on being kind to everyone consistently correlated poorly with the scale. The selection of items within this scale should be reconsidered [20]. The Control over Working Time scale worked poorly in one country, Turkey, where items on holidays and opportunities to leave the workplace showed low correlations with the scale. Differences in the local context in Turkey (e.g., legislation or company policies) might affect specific aspects of control over working time. This points at examining items in this scale across countries and industrial sectors further, possibly also through cognitive interviewing [76].

In some language versions, specific scales––in addition to those previously mentioned––had insufficient Cronbach α′s ranging from 0.62 to 0.67. These were Predictability (France, Turkey), Meaning of Work (France), Job Insecurity (France, Germany), and Work Pace (Spain). Apart from possible translation issues, it might be that local context could play a role. For example, regarding Job Insecurity, it might be that conditions at the French and German labor markets lead to a lower correlation between experience of worries getting unemployed and worries finding a new job. A reason for this could be that even if many workers in these countries have permanent contracts, opportunities for further education throughout working life are largely lacking [51].

In the international middle version, some dimensions were only measured with one item, namely Recognition, Illegitimate Tasks, Quality of Work, Horizontal Trust, and Self-rated Health. Regarding self-rated health, even if a one item measure has good predictive validity, the use of a scale could improve reliability [77]. It remains to be investigated if this is the case regarding other one-item measures. Apart from Illegitimate Tasks, the COPSOQ III instrument offers additional long version items to increase reliability.

4.1. Strengths and weaknesses

It is a strength of the questionnaire that it has been developed in a joint process by different groups of practitioners and researchers from different social and national contexts. Further it is a strength that the test presented in this article has been carried out among 23,361 employees in seven language versions across six countries (Canada, Spain, France, Germany, Sweden, and Turkey). We are not aware of a generic questionnaire being tested at the same time in so many countries and languages. Previous developments of the COPSOQ were carried out in one European country, Denmark, and only subsequently adapted and validated in other countries. By including international experience from a number of countries in the development, as well as in the validation right from the beginning of the COPSOQ III, the results of the present study are generalizable to a higher extent.

These strengths of the study must be seen in the light of some weaknesses. First, the response rate in Canada was low, and a response rate could not be calculated in France. As we are looking at associations between items in scales and associations between dimensions (measured by either scales or single items), low response rates could potentially be problematic if they led to less variation in responses. However, reliabilities estimate in the Canadian and French samples was on a similar level to that observed in countries with higher response rates. Second, we assessed reliability of scales by calculating Cronbach α. Our reason for using α is that it is widely known, making it easier for possible users to interpret our results. In practical and research settings, where groups are compared, the question of reliability is different from a clinical setting where a measurement on an individual level needs much more precision. It should be noted that with two item scales, one would not expect a very high α, as this would indicate unnecessary redundancy between the items, and potentially a lack of breadth in the information captured within the dimension under investigation. Third, owing to data protection issues (the last paragraphs in the ‘Acknowledgments’ subsection), we were not able to directly analyze DIF for evaluation of measurement invariance across countries. Given we observed differences in the reliability of scales across countries for some dimensions (e.g., Job Insecurity and Control over Working Time), DIF should be investigated in future studies.

4.2. Perspectives for further development of the COPSOQ

We now present some considerations regarding in what directions the COPSOQ could be developed and tested further in the decades to come. Our discussion focuses on reliability and validity, use of the COPSOQ in practical settings, social capital, and current trends in the working environment.

4.2.1. Reliability and validity

In the present article we have tested the reliability of scales of the COPSOQ and if dimensions of the questionnaire (represented by single items or scales) are different constructs. As previously mentioned, for both internal consistency and correlations, the results indicate differences between the samples. Some of these differences can be, of course, attributed to the fact that the Turkish, Swedish, and German data were company-based samples. However, differences in internal consistency and correlation estimates in the nationwide Canadian, Spanish, and French working populations were observed. Therefore, we recommend testing the instrument in each new language version being developed. A number of scales of the second version of the questionnaire have been tested using a test retest approach showing good reliability [66]. Test retest approaches of the new dimensions introduced in the COPSOQ III are still to come.

The overall structure of the questionnaire has previously been developed using factor analyses [2,3]. In two cases, this has already been performed regarding the present version [78,79], although additional studies are needed. Other aspects of construct validity should be tested. For example, the Swedish version has been adapted using cognitive interviewing; this approach seems to be useful for the adaption of other national versions [20]. Further aspects of validity are yet to be investigated, not only regarding the COPSOQ but also regarding psychosocial questionnaire tools in general. External validity of experienced psychosocial factors should be investigated. Questionnaire data should optimally be compared with objective measurements or other data independent of the self-report, such as observational data or registers. In addition, there is a need to achieve further knowledge about the extent to which dimensions of psychosocial working conditions attribute to different levels of work, such as the occupational level and the department/organizational level. Such studies are very rare [[80], [81], [82], [83]]. Research on the COPSOQ and the JCQ support the intention that some dimensions mainly vary between occupations (e.g., job demands, variation, and influence), whereas others do not (e.g., leadership, organizational justice, and trust) [13,61,[80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85]]. Furthermore, the predictive validity of the instrument could be tested. A challenge is that there are several relevant outcomes to consider. For example, aspects of health (e.g., self-rated health, depressive symptoms), labor market attachment (e.g., turnover intentions, exit from work), and job satisfaction. Another challenge is that evidence from longitudinal studies regarding possible effects of psychosocial factors is limited, with most of the longitudinal research in this area focusing on demands, control, and social support [11].

4.2.2. Use in practical settings

Another issue is that the discourses and practices regarding psychosocial assessments in the workplaces are very different, not only between countries but also within countries. For example, differences exist between the area of psychosocial risk assessment [86] and the area of organizational development [57,58]. With its broad coverage of concepts, the COPSOQ is applicable to both these approaches. The COPSOQ was originally developed in a risk assessment discourse and is still widely used in this context. However, the instrument also makes possible a range of analyses in an organizational development framework as suggested by the JD-R model, owing to the relatively wide scope of dimensions [72]. This wide scope was already initiated in the COPSOQ I (covering more working conditions than demands and control such as Emotional Demands and Quality of Leadership, and covering also measures of burnout and stress) and has been developed further in the COPSOQ II (e.g., Recognition, Trust, Justice) and COPSOQ III (e.g., Work Engagement and Quality of Work). To our knowledge, the various ways of using the COPSOQ in practical settings have not been documented or investigated to a large extent. It is of interest to undertake and document these analyses to facilitate the use of the instrument and exchange of experience between users.

4.2.3. Social capital

As mentioned in the introduction, the concept of social capital as an indicator of resources of the organization has gained increasing interest in practice and research [[59], [60], [61]]. A number of studies have demonstrated that high organizational social capital is strongly connected to employee well-being [13,[87], [88], [89]], customer/patient satisfaction [[90], [91], [92]], sickness absence [93], productivity [[94], [95], [96], [97]], and quality [90,91,98]. Many different indicators of organizational social capital have been applied, such as trust, justice, collaboration, mutual respect, workplace community, and common goals. In studies using the COPSOQ measures of trust, justice and collaboration have been the main indicators of social capital [13,93]. The concept of organizational capital has wide practical and theoretical implications because it is a characteristic of the whole workplace and because it does relate not only to employee well-being but also to productivity, quality, and customer satisfaction.

4.2.4. Trends

The digitalization of working life has led to new organization of work with respect to communication, place, and time [53]. There is a need to develop new measures to grasp important psychosocial aspects that arise with these developments. Particular dimensions include demands associated with the flood of information associated with electronic communication and with technological changes which have increased employer expectations of worker availability outside of work hours. Seen in hindsight, one could wonder why we have not been aware of the need for addressing this in the COPSOQ III. Whatever the answer is, this lack of coverage is shared by research of work and health in general [99]. This makes it urgent to expand the coverage of these issues in future psychosocial questionnaires.

4.2.5. The future

As the discussion of these issues indicates, the development of psychosocial questionnaires is a never-ending process. The challenge is to find a balance between needed revisions and keeping opportunities for comparisons between populations and time periods at the same time.

4.6. Concluding remarks

The present article has tested the internal consistency of the COPSOQ III instrument in six countries. Future analyses should examine various aspects of validity, using both qualitative and quantitative approaches, across further countries and industrial sectors including comparisons with, for example, observational data. Such investigations would enhance the basis for recommendations regarding the use of the COPSOQ III instrument.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank everyone making the testing of the COPSOQ III possible: The employees responding to the questionnaire; employers in Germany, Sweden, and Turkey giving access to ask their employees; data-collecting companies EKOS Probit Panel and the LegerWeb Panel (subcontracted to EKOS) in Canada, DYM-Market and Social Research in Spain, and OpinionWay in France; and all COPSOQ international network members contributing to the development process. In addition, a special thanks to the anonymous reviewers of the present article.

Regarding ethics, the Canadian data were approved by the University Ethics Board of the University of Toronto, the Spanish data by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Trade Union Institute of Work, Environment and Health (ISTAS), the French data were collected in accordance with code of Ethics of Psychologists, the German data were in accordance with the ethical standards of the German Sociological Association, the Swedish study was approved by the Regional Ethics Board in Southern Sweden (Dnr. 215/476), and the Turkish data was approved of the Dokuz Eylül University Non-Interventional Ethics Committee.

Regarding funding, the Canadian test was funded from the operating budget of the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers (OHCOW) with “in-kind” analysis assistance from the Institute for Work and Health (IWH). The Spanish field work was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness under grant PI15/00161 and PI15/00858. The French test was funded by Preventis. The German test was funded internally by the FFAW. The Swedish test was funded by AFA insurance Grant No. 130301 & the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare Grant No. 2016-07220 and the Turkish test was funded internally by the Dokuz Eylul University. The metaanalysis was funded internally by the BAuA. Those funding the national tests did not influence the analyses or interpretations of results of the present article.

The Turkish raw data can be obtained in an anonymized form. In the rest of the countries, no data are externally accessible. In Canada, participants were assured that external access could not be the case; in Spain, France, Germany, and Sweden data protection legislation prohibits it.

Appendix Table 1. The development process leading to the COPSOQ III

| Activity | Description | Participants | Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| First phase––defining contents | |||

| Delphi-like round | Item punctuation– relevance (email round) | Network members and invited researchers | Jun-Aug 2013 |

| Open comments | Email round | Network members and invited researchers | Sep 2013 |

| Discussion–Ghent COPSOQ International Workshop | First review of all comments and items COPSOQ use guidelines | Network members and invited researchers | Oct 2013 |

| Open comments analysis | Further review of all comments | Working group on comment analysis | May 2014 |

| Steering group meeting (Barcelona) | Translation check, final review of comments & items and psychometrics test | Steering Committee | Sept-Oct 2014 |

| Network's comment round | Email round | Network members and invited researchers | Jan-Mar 2015 |

| Steering group meeting (Malmö) | Review of comments and items, Swedish cognitive interviews, and psychometrics test | Steering Committee | Jun 2015 |

| COPSOQ uses criteria | Defining use criteria for research and risk assessment | Working group on use criteria | Jun 2015-May 2018 |

| Network's comment round | Email round | Network members and invited researchers | Jul-Aug 2015 |

| Draft proposal and criteria sent to all networks | Steering Committee | Sep 2015 | |

| Discussion–– the Paris COPSOQ International Workshop | Review of all comments and items of the draft proposal and the COPSOQ use criteria | Network members and invited researchers | Oct 2015 |

| Final network's comment round | Email round | Network members and invited researchers | Dec 2015-Apr 2016 |

| Beta version | Review of last comments, launch beta version | Steering Committee | May 2016 |

| Second phase––empirical testing | |||

| Data collection | Diverse methods depending on the country | Network research groups | Dec 2016-Dec 2017 |

| Steering group meeting (Berlin) | Defining hypothesis and statistical analysis | Steering Committee | March 2017 |

| Data analysis | Metaanalysis | Steering Committee and invited researchers | Oct 2017-Apr 2018 |

| Final phase––agreement | |||

| Discussion –Santiago de Chile COPSOQ International Workshop | Discussion of results | Network members and invited researchers | Nov 2017 |

| Launching the COPSOQ III | Presenting the COPSOQ III for a wider audience. | Steering Committee | November 2019 |

COPSOQ = Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire.

Appendix Table 2. Definitions of dimensions of the COPSOQ III

| Domain | Dimension | Name | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demands at Work | Quantitative Demands | QD | Quantitative Demands deal with how much one has to achieve in ones work. Quantitative Demands can be assessed as an incongruity between the amount of tasks and the time available to perform these tasks in a satisfactory manner. |

| Work Pace | WP | Work Pace deals with the speed at which tasks have to be performed. Work Pace is a measure of the intensity of work. | |

| Cognitive Demands | CD | Cognitive Demands deal with demands involving the cognitive abilities of the worker | |

| Emotional Demands | ED | Emotional Demands occur when the worker has to deal with or is confronted with other people's feelings at work. Other people comprise both people who are not employed at the workplace, e.g., customers, clients, or pupils, and people employed at the workplace, such as colleagues, superiors, or subordinates. | |

| Demands for Hiding Emotions | HE | Demands for Hiding Emotions occur when the worker has to conceal her or his own feelings at work from other people. Other people comprise both people who are not employed at the workplace, e.g., customers, clients, or pupils, and people employed at the workplace, such as colleagues, superiors, or subordinates. | |

| Work Organization and Job Contents | Influence at Work | IN | Influence at Work deals with the degree to which the employee can influence aspects of work itself, ranging from, e.g., planning of work to e.g., the order of tasks. |

| Possibilities for Development | PD | Possibilities for Development deal with if the tasks are challenging for the employee and if tasks provide opportunities for learning, and thus provide opportunities for development not only in the job but also at the personal level. Lack of development can create apathy, helplessness, and passivity. | |

| Variation of Work | VA | Variation of Work deals with the degree to which work (tasks, work process) is varied or not, that is, if tasks are not repetitive or repetitive. | |

| Control over Working Time | CT | Control over Working Time deals with the degree to which the employee can influence conditions surrounding work, e.g., breaks, length of the working day, or work schedules. | |

| Meaning of Work | MW | Meaning of Work concerns both the meaning of the aim of work tasks and the meaning of the context of work tasks. The aim is “vertical”, i.e., that the work or product is related to a more general purpose, such as healing the sick or to produce useful products. The context is “horizontal”, i.e., that one can see how ones' own work contributes to the overall product of the organization. | |

| Interpersonal Relations and Leadership | Predictability | PR | Predictability deals with the means to avoid uncertainty and insecurity. This is achieved if the employees receive the relevant information at the right time. |

| Recognition | RE | Recognition deals with the recognition by the management of your effort at work. | |

| Role Clarity | CL | Role Clarity deals with the employee's understanding of her or his role at work, i.e., content of the tasks, expectations to be met, and her or his responsibilities. | |

| Role Conflicts | CO | Role Conflicts stem from two sources. The first source is about possible inherent conflicting demands within a specific task. The second source is about possible conflicts when prioritizing different tasks. | |

| Illegitimate Tasks | IT | Illegitimate Tasks cover tasks that violate norms about what an employee can properly be expected to do because they are perceived as unnecessary or unreasonable; they imply a threat to one's professional identity. | |

| Quality of Leadership | QL | Quality of Leadership deals with the next higher managers' leadership in different contexts and domains. | |

| Social Support from Colleagues | SC | Social Support from Colleagues deals with the employees' impression of the possibility to obtain support from colleagues if one should need it. | |

| Social Support from Supervisors | SS | Social Support from Supervisors deals with the employees' impression of the possibility to obtain support from the immediate superior if one should need it. | |

| Sense of Community at Work | SW | Sense of Community at Work concerns whether there is a feeling of being part of the group of employees at the workplace, e.g., if employees relations are good and if they work well together. | |

| Work–Individual Interface | Commitment to the Workplace | CW | Commitment to the Workplace deals with the degree to which one experiences being committed to ones' workplace. It is not the work by itself or the work group that is the focus here, but the organization in which one is employed. |

| Work Engagement | WE | This dimension deals with the attachment you feel to the task independently of how you experience your workplace [69]. | |

| Job Insecurity | JI | Job Insecurity deals with aspects of security of the employment of the employee, e.g., regarding the risk of being fired or the certainty of being reemployed if fired. | |