Abstract

The unceasing emerging of multidrug-resistant bacteria imposes a global foremost human health threat and discovery of new alternative remedies are necessity. The use of plant essential oil in the treatment of many pathogenic bacteria is promising. Acne vulgaris is the most common skin complaint that fears many people about their aesthetic appearance. In this work we investigated the antibacterial activity of some plant oils against acne-inducing bacteria. Three bacterial isolates were identified from Egypt, biochemically and by means of 16s rRNA gene typing, and were designated as Staphylococcus aureus EG-AE1, Staphylococcus epidermidis EG-AE2 and Cutibacterium acnes EG-AE1. Antibiotic susceptibility test showed resistance of the isolates to at least six antibiotics, yet they are still susceptible to the last resort Vancomycin. In vitro investigations of eleven Egyptian plant oils, identified tea tree and rosemary oils to exhibit antibacterial activity against the antibiotic-resistant acne isolates. Inhibition zones of 15 ± 0.5, 21.02 ± 0.73 and 20.85 ± 0.76 mm was detected when tea tree oil applied against the above-mentioned bacteria respectively, while inhibition zones of 12.5 ± 1.5, 15.18 ± 0.38 and 14.77 ± 0.35 mm were detected by rosemary oils. Tea tree and rosemary oils exhibited bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity against all the strains with MICs/MBCs ranging between 39-78 mg/L for tea tree oil and 39–156 mg/L for rosemary oil. All the isolates were killed after 4 and 6 h upon growing with 200 mg/L of tea tree and rosemary oils, respectively. Additionally, gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC/MS) profiling identified and detected a variable number of antimicrobial compounds in both oils.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, Multidrug-resistant bacteria, Natural oil, Egypt, Minimum inhibitory concentration, GC–MS

1. Introduction

Acne vulgaris is considered the most common skin complaint that worries many people about their aesthetic appearance and generally impaired quality of life is well informed (Dunn et al., 2011, Gieler et al., 2015, Sarkar et al., 2016). The microbiology and therapy of acne vulgaris constitute the foremost thrust of current research in the clarification of the causal pathogens and new modes of treatments. Cutibacterium acnes (formerly known as Propionibacterium acnes (Scholz and Kilian, 2016) are aerotolerant anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. It was originally identified as Bacilli acnes (Gilchrist, 1900), because of its ability to generate propionic acid it was named later as P. acnes. However recently biochemical and genomic studies resulted in a taxonomical reclassification of P. acnes and a novel genus Cutibacterium was designated for the cutaneous species (Dréno et al., 2018, Scholz and Kilian, 2016).

Although C. acnes bacteria normally commensal on the surface of healthy skin, they anaerobically proliferate deeply within follicles and pores (Dréno et al., 2018) by metabolizing sebum triglycerides from the surrounding skin tissues and use it as a primary source of energy and nutrients. On the contrary, Staphylococcus epidermidis is a gram-positive, facultative anaerobic organism, usually involves superficial infections within the sebaceous unit (Burkhart et al., 1999). Different treatment strategies are to be considered including decreasing hyperkeratinization, microbial colonization, sebum production and inhibiting the inflammation (Zaenglein et al., 2016) which is selected on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, emerging strategies considering the modification of the existing drugs and the progress of new medications targeting the regulatory pathways involved in acne pathophysiology (Tuchayi et al., 2015).

Topical antibiotics and/or chemical peeling agents are being used currently in acne vulgaris treatments, however oral antibiotics, retinoids, or hormones are prescribed daily (Pineau et al., 2019). The most frequently used oral remedies include the tetracyclines (tetracycline, minocycline, and doxycycline), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and macrolides (erythromycin and azithromycin) (Farrah and Tan, 2016, Leyden, 2003). Acne pharmacotherapies are effective but are associated with adverse events such as mood disorders, antibiotic-resistance and can leave the skin dry with irritation feelings (Eichenfield, 2015). A most important drawback of current therapies is that daily intake of antibiotics, resulted in developing multidrug resistant bacteria (Van den Bergh et al., 2016). Furthermore, many countries have identified increasing the resistance of Acne bacteria to topical macrolides (Walsh et al., 2016) and active antibiotic gel (Mills et al., 2002).

The emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria has become a foremost health threat, afterward, interests in alternative medicine have been increased rather than traditional antibiotic medications for skin conditions (Neamsuvan et al., 2015). The antibacterial potential of lipids has been long recognized (Nikkari, 1974). A previous study on the therapeutic potential of free fatty acids (FFAs) against methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) showed that only oleic acid (C18:1, cis-9) disrupted the MRSA cell wall at small doses (Chen et al., 2011).

In Egypt, most of the former studies on Acne vulgaris focused only on the prevalence and the clinical features of patients with Acne, there is no actual search for herbal therapy. Accordingly, we have designed this study to isolate the acne-inducing bacteria and to shed light on the efficacy of using the essential oils of some of the Egyptian domestic medicinal herbs in the treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and sample collection

Pathological diagnosis examination of Fifty-five patients (20 males and 35 females) at the adolescent age of 17–25 years old, attending Benha university hospital dermatology clinic, with potential inflammatory acne skin lesions, from 2016 to 2018, were included in the study. Patients showed overproduction of sebum and follicular hyperkeratosis which resulted in the development of microcomedones. Inflammatory and non-inflammatory acne lesions were punctured with a hypodermic needle and the contents were collected with a comedone extractor under complete aseptic condition. Patients with pregnancy, Drug addicts, patients with endocrinal problems, adrenal dysfunction and those taking contraceptives were excluded. Basic clinical information (including age, gender, age of onset and duration of disease) and previous consultation records were obtained at the time of patient registration. Three samples were taken from each patient and were then inserted into Thioglycolate broth tube as a transport media and sent immediately to the Microbiology and Immunology department (Benha University, Egypt). The samples were inoculated onto sheep blood agar medium at 37 °C under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions for 2–7 days.

2.2. Biochemical identification and 16s rRNA gene sequencing

The collected samples were grown both aerobically and anaerobically, only 35 out of the 55 patients showed bacterial growth on the selective media. Biochemical properties (Table S1, Supplementary data) identified two different groups of the aerobic isolates were found to be gram-positive cocci, non-motile and were arranged in grape-like clusters. Anaerobic isolates were gram-positive polymorphic bacilli and were able to ferment glucose with acid production, the biochemical profile of the anaerobic bacteria (as shown in Table S1) was consistent with those of formerly known as Propionibacteria.

The partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing was used to confirm the biochemical identification. Universal 16s rRNA primers 8F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GACGGGCGGTGTGTRCA-3′) (Turner et al., 1999) were used to amplify these genes in the aerobic isolates, however, PAS9 (5′-CCCTGCTTTTGTGGGGTG-3′), PAS10 (5′-CGCCTGTGACGAAGCGTG-3′) and PAS11 (5′-CGACCCCAAAAGAGGGAC-3′) (Nakamura et al., 2003) amplified the 16s rRNA of anaerobic bacteria. Sanger sequences were generated at Sigma company Genomics Core Facility (Cairo, Egypt) using an ABI PRISM 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Life Technologies Corporation, CA). Sequences similarity were conducted using the BLASTn search at the NCBI website (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA software version X (Kumar et al., 2018).

2.2.1. Isolates accession numbers

Staphylococcus aureus EG-AE1, Staphylococcus epidermidis EG-AE2 and Cutibacterium acnes EG-AE1 were deposited in the GeneBank database and were assigned the accession numbers MK934843.1, MK937638.1 and MN336167.1 respectively.

2.3. Antibiotic susceptibility test

Antibiotics susceptibility testing was performed using the disc diffusion method (Biemer, 1973) for the following antibiotics (Oxoid, UK); Azithromycin (AZM 15 µg), Amoxicillin + Clavulanic Acid (AMC 20 + 10 µg), Ciprofloxacin (CIP 1 µg), Erythromycin (E 15 µg), Penicillin-G (P 10 µg), Tobramycin (TOB 10 µg), Tetracycline (TEC 30 µg), Cephalexin (CN 30 µg), Clindamycin (DA 2 µg), Chloramphenicol (CL 30 µg), Amikacin (AK 30 µg), Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT 25 µg), Rifampin (RA 5 µg) and Vancomycin (V 30 µg). The results were inferred according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (Wayne, 2019).

2.4. Antibacterial activity of some plant oils

Agar well diffusion method (Balouiri et al., 2016, Magaldi et al., 2004, Valgas et al., 2007) was used to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of the following plant oils; Tea tree, Cinnamon, Rosemary, Cactus, Lavender, Basil, Lemon, Thyme, Parsley, Almond and Lupine. The crude oils were purchased from the commercial markets in Egypt. Nutrient agar plates were inoculated by spreading a 100 µl of the actively grown bacteria. A sterile cork was used to punch holes with a diameter of 6–8 mm and 10 µl of the tested oils (200 mg/L) was introduced into the well. The inoculated agar plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Diameters of the inhibition zones were measured as (mm).

2.5. MICs and MBCs of tea tree and rosemary oils

The MIC of tea tree and rosemary oils were determined using a broth assay (Klančnik et al., 2010) in 96-well microtiter plates (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Fresh cultures of the tested isolates were prepared in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth, inocula of concentrations 2 × 107 cfu/ml were used. A two-fold dilution series of tea tree and rosemary oils were prepared in 1% DMSO to yield final concentrations ranging from 5000 mg/L to 9.7 mg/L. Chloramphenicol was employed as a positive control. After 18 h and 48 h (for C. acne), the optical density at 600 nm was measured with a microplate reader (680 XR reader, Bio-Rad). Bacterial growth was confirmed by adding 10 μl of a sterile 0.5% aqueous solution of triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma–Aldrich) and incubating at 36 °C for 30 min. The viable bacterial cells reduced the yellow TTC to pink/red 1,3,5-triphenylformazan (TPF). All assays were performed in triplicate. Streaks were taken from the two lowest concentrations of each oil concentration exhibiting invisible growth and were sub-cultured onto Blood agar media. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h, then inspected for bacterial growth in corresponding to both the oils. MBC was taken as the concentration of the oil that did not exhibit any bacterial growth.

2.6. Time-kill kinetics

This experiment was performed as described previously (May et al., 2000). Prior to the experiment, bacteria were incubated on IsoSensitest broth (ISB; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) for 90 mins at 37 °C to ensure that all the bacteria were in the action in the logarithmic growth phase. The initial bacterial concentration was measured as cfu/ml. Each isolate was inoculated into three flasks, one as growth control, one for each type of oil. All flasks were incubated at 37 °C while shaking at 150 rpm. Aliquots were taken at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4 and 6 and viable colony counts on blood agar were calculated as cfu/ml.

2.7. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis

GC/MS analysis of the major essential constituents of the oils of tea tree and rosemary was carried out using the GC Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA) using 6890 N apparatus equipped with the split-splitless injector attached to HP-5 fused silica column (30 m × 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 µm) and interfaced to flame-ionization detector (FID). 1 µl of ethanol diluted oil was injected under the following operational conditions: carrier gas was He (1 ml/min); the temperatures were set as follows: injector at 250 °C and detector at 280 °C, while the column temperature was linearly programmed from 40 °C to 260 °C at 4 °C/min. Constituents were identified by comparison of their spectral outcomes with those available on MS libraries (NIST/Wiley), and by comparison of their retention profile (calibrated AMDIS), with the data from the literature (Adams, 2005).

2.8. Ethical approval

Prior to the study, a formal consensus was obtained from all patients at Benha University Hospital.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Isolation, biochemical characterization and 16S rRNA typing of acne vulgaris

The collected samples were grown both aerobically and anaerobically, only 35 out of the 55 patients showed bacterial growth on the selective media. Biochemical properties (Table S1, Supplementary data) identified two different groups of the aerobic isolates were found to be gram-positive cocci, non-motile and were arranged in grape-like clusters. Anaerobic isolates were gram-positive polymorphic bacilli and were able to ferment glucose with acid production, the biochemical profile of the anaerobic bacteria was consistent with those of formerly known as Propionibacteria.

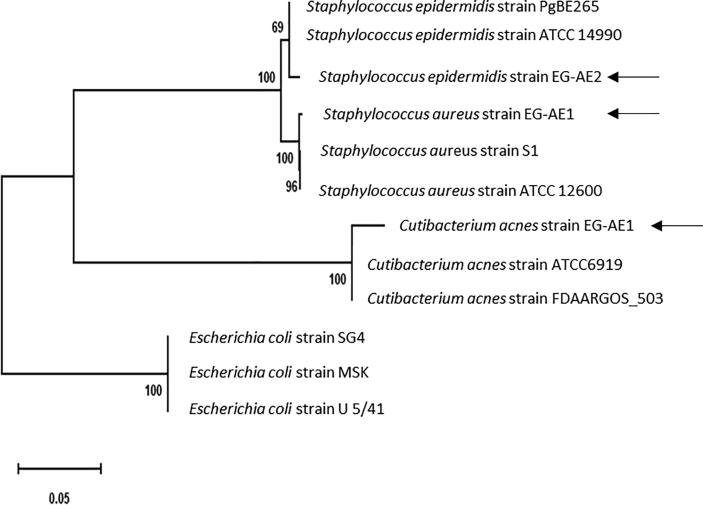

BLASTn alignments and phylogenetic tree analysis (Fig. 1) of the assembled 16s rRNA gene sequences showed highest similarities with the previously partially sequenced 16S rRNA of Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis and Cutibacterium acnes on the NCBI website. Bacteria were designated as Staphylococcus aureus strain EG-AE1, Staphylococcus epidermidis strain EG-AE2 and Cutibacterium acnes Strain EG-AE1 and they were detected at frequencies of 21%, 37% and 42% of the subjects in acne patients respectively. Previous investigations on acne vulgaris showed that S. epidermidis and C. acne are the most significant major groups in patients with acne (Burkhart et al., 2015, Burkhart et al., 1999, Dhillon and Varshney, 2013), though there are many evidences suggesting potential pathogenic roles of S. aureus in acne vulgaris inflammation via stimulation of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and local immunosuppression (Khorvash et al., 2012, Totté et al., 2016).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree shows the evolutionary relationships between the 16s rRNA sequences of the isolated acne bacteria with their bacterial concatenated nucleotide sequences of their 16s rRNA. The Maximum Likelihood tree was constructed using the MEGA X software with the Maximum Likelihood algorithm and default setting. The bar length represents 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide site. The new acne isolates in the current study are indicated by black arrows. Branch support was estimated from 1000 bootstrap replicates. Three E. coli 16s rRNA sequences serve as outgroups to root the tree.

3.2. Antibiotic susceptibility testing

Qualitative results from the antibiograms (Table 1) showed that both S. aureus EG-AE1 and S. epidermidis EG-AE2 were resistant to at least eight antibiotics (Azithromycin, Erythromycin, Penicillin-G, Tetracycline, Clindamycin, Amikacin, Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and Rifampin). C. acnes EG-AE1 were found to be resistant to (Azithromycin, Erythromycin, Tetracycline, Clindamycin, Amikacin and Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole). Yet, the three isolates were susceptible to Chloramphenicol and Vancomycin.

Table 1.

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of the isolated acne bacteria against a selection of fourteen antibiotics.

| Bacteria | AZM | AMC | CIP | E | P | TOB | TEC | CN | DA | CL | AK | SXT | RA | VA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staph. aureus strain EG-AE1 | R* | I* | I | R | R | I | R | I | R | S* | R | R | R | S |

| Staph. epidermidis strain EG-AE2 | R | I | I | R | R | I | R | I | R | S | R | R | R | S |

| Cutibacterium acnes Strain EG-AE1 | R | S | I | R | S | S | R | S | R | S | R | R | I | S |

Azithromycin (AZM 15 µg), Amoxicillin + Clavulanic Acid (AMC 20 + 10 µg), Ciprofloxacin (CIP 1 µg), Erythromycin (E 15 µg), Penicillin-G (P 10 µg), Tobramycin (TOB 10 µg), Tetracycline (TEC 30 µg), Cephalexin (CN 30 µg), Clindamycin (DA 2 µg), Chloramphenicol (CL 30 µg), Amikacin (AK 30 µg), Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT 25 µg), Rifampin (RA 5 µg) and Vancomycin (V 30 µg).

Denotes for Resistant (R), Intermediate (I) and Susceptible (S).

Antibiotic resistant bacteria have reached a worrying stage all over the world, mainly in the developing countries (Amann et al., 2019, Blomberg et al., 2004, Kunin, 1993, Omulo et al., 2015, Slack, 1989, Williams et al., 2018). Egypt is one of the countries that have less severe restrictions on antibiotic prescription (Awad et al., 2016, Hassan et al., 2011, Ibrahim, 2012, Khalil, 2012, Sabry et al., 2014, Sobhy et al., 2012), the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria is unceasing very quickly. A major reason is that antibiotics can be purchased directly from drug retailers and pharmacies without a prescription (Sosa et al., 2010, Istúriz and Carbon, 2000, Llor and Cots, 2009, Volpato et al., 2005). In 2017 the Center for Disease and Control Prevention announced that at least 2 million people in the U.S. are infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria each year and at least 23,000 of them die.

Antibiotic-resistant Staphylococci are a worldwide problem affecting humans, animals and numerous natural environments (Fitzgerald, 2012, Grundmann et al., 2006, Vindel et al., 2014). Similarly, the overall occurrence of C. acnes antibiotic resistance has increased dramatically last years, a previous study showed that it rises from 20% in 1987 to 62% in 1996 (Leyden and Levy, 2001), later it was detected the resistance of C. acnes to multiple drugs such as Erythromycin, Clindamycin, Tetracycline (Ross et al., 1998), Azithromycin, Minocycline, Doxycycline and Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Moon et al., 2012, Schafer et al., 2013).

3.3. Antibacterial activity of some plant oils against the acne bacteria

The antimicrobial activity of a selection of eleven medicinal plant oils against the isolated bacteria was investigated and the results are summarized in Table 2. Out of the tested oils, only oils of tea tree and rosemary were effective against the acne bacteria. Tea tree oil was found to be more effective than rosemary oil against S. aureus, S. epidermidis and C. acnes with inhibition zones of 15.5 ± 0.50 mm, 21.02 ± 0.73 mm and 20.85 ± 0.76 mm respectively.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of different plant oils on the isolated acne bacteria. Each value is the mean of three readings (mm) ± Standard Error (SE).

| Bacteria | Inhibition zones (mm) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tea tree | Cinnamon | Rosemary | Cactus | Lavender | Basil | Lemon | Thyme | Parsley | Almond | Lupine | |

| Staph. aureus strain EG-AE1 | 15.5 ± 0.50 | R | 12.5 ± 1.5 | R* | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Staph. epidermidis strain EG-AE2 | 21.02 ± 0.73 | R | 15.18 ± 0.38 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Cutibacterium acnes Strain EG-AE1 | 20.85 ± 0.76 | R | 14.77 ± 0.35 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

Denotes for Resistant or no inhibition (R).

The dreading continuous emergence of multidrug resistance strains led the investigators to develop new alternative treatment options. Of those medicinal plants are promising, medicinal plants are being used since ever in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases (Bhuchar et al., 2012) and likely, they are safe, cheaper and have low side effects (Rafieian-kopaei, 2012, Singh et al., 2013). It is very common to use medicinal plants in the treatment of acne and skin infectious diseases (Bhuchar et al., 2012). Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) oil (TTO) is known since long for many remedial uses and has been claimed as a potential candidate to replace antibiotics particularly in topical applications (Carson et al., 2006). Early studies on the antimicrobial activity of TTO claimed that TTO to be more active against antibiotic-resistant bacteria (Carson et al., 2005). Furthermore, it is added as an active constituent in many topical formulations used for the treatment of cutaneous infections for controlling dandruff, acne, lice, herpes and other skin infections (Pazyar et al., 2013). Previous studies showed that the methanolic extract of Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary) has a good inhibition against S. aureus (Issabeagloo et al., 2012) and C. acnes (Vora et al., 2018).

3.4. Minimum inhibitory (MICs) and Minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC)

The MIC and MBC of the most effective oils (tea tree and rosemary oils) were examined to evaluate their bacteriostatic and bactericidal properties and were recorded in Table 3. The MICs/MBCs of tea tree oil against S. aureus and S. epidermidis were found to be 78 mg/L, though the growth of these two isolates were inhibited by 156 mg/L of rosemary oil. Both tea tree and rosemary oils inhibited C. acnes at 39 mg/L. Our results showed that, both tea tree and rosemary oils showed potentially bactericidal activity against the tested pathogenic bacteria, however, tea tree oil showed more potency. Previous studies on antimicrobial activity of tea tree oil reported MICs of 125 mg/L (Carson et al., 2006, Cox et al., 2000) to 2000 mg/L (Banes-Marshall et al., 2001, Carson et al., 2006, Cox et al., 2000).

Table 3.

Minimal inhibitory (MIC) and minimal bactericidal (MBC) concentrations of the tea tree and Rosemary oils against the isolated bacteria. The concentrations were measured as oil (mg/L).

| Bacteria | Tea tree oil |

Rosemary oil |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| Staph. aureus strain EG-AE1 | 78 | 78 | 156 | 156 |

| Staph. epidermidis strain EG-AE2 | 78 | 78 | 156 | 156 |

| Cutibacterium acnes Strain EG-AE1 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

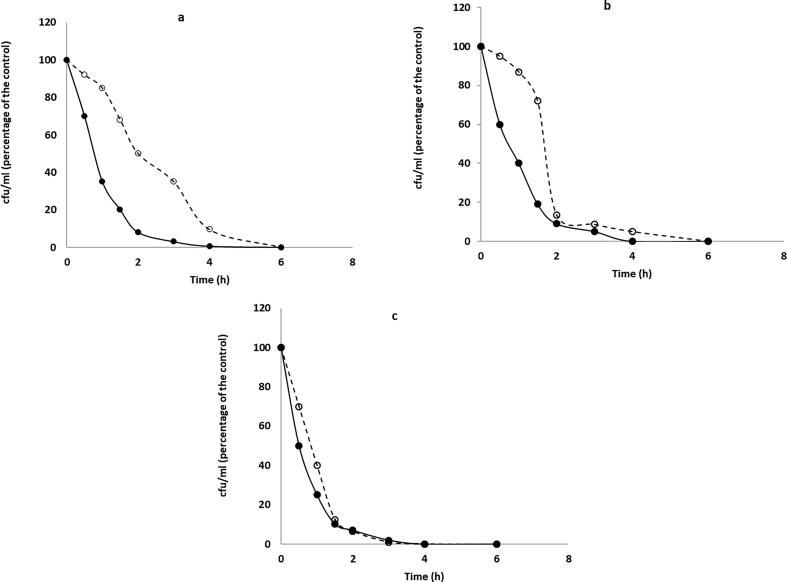

3.5. Time-kill kinetics of tea tree and rosemary oils

Measurements of killing time by the tea tree and rosemary oils were made for each oil individually and are shown in Fig. 2. Tea tree oil showed greater activity than rosemary oil against all the isolates. S. aureus, S. epidermidis and C. acnes were killed by tea tree oil within 4 h. However, rosemary oil killed all the isolated by 6 h. A previous study on the time of killing of the standard tea tree oil and other chemically different tea tree oils against Staphylococcus aureus exhibited variable killing times (May et al., 2000). Apparently, the chemistry of the oils has a great impact on the efficacy and timing of action.

Fig. 2.

Time-kill experiment of S. aureus (a), S. epidermidis (b) and C. acnes (c); Relative viable count of the three isolates were measured for 6 h and calculated as cfu/ml (% of the control) against tea tree oil (solid line with filled circle), rosemary oil (dashed line with open circles). Prior to the experiment, all the bacteria were in the action of the logarithmic phase. Aliquots were taken at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4 and 6 and viable colony counts on blood agar were calculated as cfu/ml.

3.6. GC–MS profiles

GC/MS chromatographs (Figs. 3–4, Supplementary data) identified and estimated the presence of twelve and eleven major compounds in the ethanolic extracts of tea tree and rosemary oils respectively, the detected compounds are complex mixtures of terpenes and related alcohols. The constituents, as well as their therapeutic functions, are listed in Table 4. Nine compounds were detected in both oils (α-Pinene, 2-tert-Butyl-4-isopropyl-5-methylphenol, Camphene, Sabinene, Myrcene, 13-Methyltetradecanoic acid, p-Cymene, α-Terpinene and γ-Terpinene). Most of those compounds were detected previously in the extracts of tea tree (Brophy et al., 1989) and rosemary oils (Jiang et al., 2011).

Table 4.

Major constituents of Tea tree and Rosemary oils as identified by GC/MS analysis.

| No | List of identified components | Chemical structure | Tea tree oil | Rosemary oil | Known functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Methyl pentanoate | C6H12O2 | +* | nd | In fragrances, beauty care, soap, laundry detergents |

| 2 | 6-Methyl-3,5-heptadien-2-one | C8H12O | + | nd | Flavor and fragrance agents |

| 3 | α-Pinene | C10H16 | + | + | Anti-inflammatory via and seems to be an antimicrobial. |

| 4 | 2-tert-Butyl-4-isopropyl-5-methylphenol | C14H22O | + | + | It’s an isomer of Cashmeran (known as musk indanone) which is used in fragrances |

| 5 | Camphene | C10H16 | + | + | Powerful pain relieving, anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties. |

| 6 | Sabinene | C10H16 | + | + | Anti-inflammatory agent, antibacterial and antifungal agent |

| 7 | Myrcene | C10H16 | + | + | Anti-inflammatory, analgesic (pain relief), antibiotic, sedative and antimutagenic |

| 8 | 13-Methyltetradecanoic acid | C15H30O2 | + | + | induces apoptosis or “programmed cell death” of certain human cancer cells. |

| 9 | p-Cymene | C10H14 | + | + | pain-relieving, anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties |

| 10 | α-Terpinene | C10H16 | + | + | Fragrance compound, antioxidant |

| 11 | γ-Terpinene | C10H16 | + | + | A scent in 60% −80% of perfumed hygiene products and cleaning agents as soap, detergents, Shampoos and lotions. |

| 12 | Linalool | C10H18O | + | nd | Anti-anxiety, Antidepressant, Sedative, Anti-inflammatory, Anti-epileptic and Analgesic |

| 13 | β-Pinene | C10H16 | nd* | + | Antimicrobial and Flavoring Agent. |

| 15 | Thymol | C10H14O | nd | + | Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory. |

+Denotes for detected constituents and not detected (nd).

Interestingly, a web search of the therapeutic functions for the identified compounds displayed antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. Besides, some other detected compounds are being used in fragrances, beauty care, soap and laundry detergents. All of this supports the potential use of both tea tree and rosemary oil to be used as antimicrobial agents against acne-inducing bacteria. Interestingly, the efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of a tea tree oil gel and face wash on acne patients showed a significant improvement in mild to moderate acne and that the products were well tolerated (Malhi et al., 2017). Moreover, a mixed cream formula of 20% propolis, 3% “tea tree oil”, and 10% “Aloe vera” was found to be better than a 3% erythromycin cream in reducing erythema scars, acne severity index, and total lesion count (Mazzarello et al., 2018). However, limited data are available on the cytotoxicity of both oils and more in vivo work is to be done to confirm this.

4. Conclusion

This manuscript describes the isolation of three groups of acne-inducing bacteria; Staphylococcus aureus EG-AE1, Staphylococcus epidermidis EG-AE2 and Cutibacterium acnes EG-AE1 from Egypt. The antibacterial effects of some medicinal plant oils were tested against the isolated bacteria, oils of tea tree and rosemary were found to be rich sources for essential oils with many therapeutic uses. Both are considered good candidates to replace antibiotics in acne therapy. For future in vivo studies, concentrations up to 78 mg/L and 156 mg/L of the tea tree oil and rosemary respectively to be applied as a topical prescription. Currently, we are investigating the efficacy of certain types of nanoparticles and phage therapy as new approaches to treat acne bacteria.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the financial supports from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (31750110464); Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Benha University, Egypt, and Huazhong Agricultural University, Talented Young Scientist Program (TYSP Grant No.42000481-7). All authors listed have made a direct, substantial and intellectual contribution to this work therefore approved it for publication.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.11.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Adams R. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/quadrupole mass spectroscopy. Carol Stream. 2005;16:65–120. [Google Scholar]

- Amann S., Neef K., Kohl S. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2019;26:175–177. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2018-001820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad H.A., Mohamed M.H., Badran N.F., Mohsen M., Abd-Elrhman A.S.A. Multidrug-resistant organisms in neonatal sepsis in two tertiary neonatal ICUs, Egypt. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2016;91:31–38. doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000482038.76692.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balouiri M., Sadiki M., Ibnsouda S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: a review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banes-Marshall L., Cawley P., Phillips C.A. In vitro activity of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil against bacterial and Candida spp. isolates from clinical specimens. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2001;58:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuchar S., Katta R., Wolf J. Complementary and alternative medicine in dermatology: an overview of selected modalities for the practicing dermatologist. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2012 doi: 10.2165/11597560-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemer J.J. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing by the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1973;3:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg B., Mwakagile D.S.M., Urassa W.K., Maselle S.Y., Mashurano M., Digranes A., Harthug S., Langeland N. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance at a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2004;4 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy J.J., Davies N.W., Southwell I.A., Stiff I.A., Williams L.R. Gas Chromatographic Quality Control for Oil of Melaleuca Terpinen-4-ol Type (Australian Tea Tree) J. Agric. Food Chem. 1989;37:1330–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart C.G., Burkhart C.N., Lehmann P.F. Classic diseases revisited: Acne: a review of immunologic and microbiologic factors. Postgrad. Med. J. 2015;75:328–331. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.884.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart, C.G., Burkhart, C.N., Lehmann, P.F., 1999. Acne: a review of immunologic and microbiologic factors. Postgrad. Med. J. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.75.884.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carson, C.F., Hammer, K.A., Riley, T.V., 2006. Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil: a review of antimicrobial and other medicinal properties. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.19.1.50-62.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carson C.F., Messager S., Hammer K.A., Riley T.V. Tea tree oil: a potential alternative for the management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Aust. Infect. Control. 2005;10:32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.H., Wang Y., Nakatsuji T., Liu Y.T., Zouboulis C.C., Gallo R.L., Zhang L., Hsieh M.F., Huang C.M. An innate bactericidal oleic acid effective against skin infection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a therapy concordant with evolutionary medicine. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;21:391–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox S.D., Mann C.M., Markham J.L., Bell H.C., Gustafson J.E., Warmington J.R., Wyllie S.G. The mode of antimicrobial action of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree oil) J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000;88:170–175. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De J. Sosa, A., Byarugaba, D.K., Amabile-Cuevas, C.F., Hsueh, P.R., Kariuki, S., Okeke, I.N., 2010. Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries, Antimicrob. Resist. Develop. Countr. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-89370-9.

- Dhillon K., Varshney K.R. Study of microbiological spectrum in acne Vulgaris: an in vitro study. Sch. J. Appl. Med. Sci. 2013;1:724–727. [Google Scholar]

- Dréno B., Pécastaings S., Corvec S., Veraldi S., Khammari A., Roques C. Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and acne vulgaris: a brief look at the latest updates. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018 doi: 10.1111/jdv.15043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L.K., O’Neill, J.L., Feldman, S.R., 2011. Acne in adolescents: Quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol. Online J. [PubMed]

- Eichenfield L. Evolving perspective on the etiology and pathogenesis of Acne Vulgaris. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrah, G., Tan, E., 2016. The use of oral antibiotics in treating acne vulgaris: a new approach. Dermatol. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12370. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald J.R. Livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus: origin, evolution and public health threat. Trends Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieler U., Gieler T., Kupfer J.P. Acne and quality of life - impact and management. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereol. 2015;29:12–14. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist T.C. A bacteriological and microscopical study of over 300 vesicular and pustular lesions of the skin, with a research upon the etiology of acne vulgaris. Johns Hopkins Hosptl. Rep. 1900;9:400–430. [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann H., Aires-de-Sousa M., Boyce J., Tiemersma E. Emergence and resurgence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a public-health threat. Lancet. 2006 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A.M., Ibrahim O., El Guinaidy M. Surveillance of antibiotic use and resistance in Orthopaedic Department in an Egyptian University Hospital. Int. J. Infect. Control. 2011;7 [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim O.H.M. Evaluation of drug and antibiotic utilization in an Egyptian University Hospital: an interventional study. Intern. Med. Open Access. 2012;02 [Google Scholar]

- Issabeagloo E., Kermanizadeh P., Taghizadieh M., Forughi R. Antimicrobial effects of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) essential oils against Staphylococcus spp. African J. Microbiol. Res. 2012;6:5039–5042. [Google Scholar]

- Istúriz R.E., Carbon C. Antibiotic use in developing countries. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2000;21:394–397. doi: 10.1086/501780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Wu N., Fu Y.J., Wang W., Luo M., Zhao C.J., Zu Y.G., Liu X.L. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Rosemary. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2011;32:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil R.B. PRM58 Turning the Implausible to the Plausible: Towards a Better Control of Over the Counter Dispensing of Antibiotics in Egypt. Value Heal. 2012;15:A169. [Google Scholar]

- Khorvash F., Abdi F., Kashani H.H., Naeini F.F., Narimani T. Staphylococcus aureus in acne pathogenesis: a case-control study. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2012;4:573–576. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.103317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klančnik A., Piskernik S., Jeršek B., Možina S.S. Evaluation of diffusion and dilution methods to determine the antibacterial activity of plant extracts. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2010;81:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin, C.M., 1993. Resistance to antimicrobial drugs - A worldwide calamity. Ann. Intern. Med. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leyden J., Levy S. The development of antibiotic resistance in Propionibacterium acnes. Cutis. 2001;67:21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyden J.J. A review of the use of combination therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003;49 doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llor C., Cots J.M. The sale of antibiotics without prescription in pharmacies in Catalonia. Spain. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48:1345–1349. doi: 10.1086/598183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaldi S., Mata-Essayag S., Hartung De Capriles C., Perez C., Colella M.T., Olaizola C., Ontiveros Y. Well diffusion for antifungal susceptibility testing. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;8:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2003.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhi H.K., Tu J., Riley T.V., Kumarasinghe S.P., Hammer K.A. Tea tree oil gel for mild to moderate acne; a 12 week uncontrolled, open-label phase II pilot study. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2017;58:205–210. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May J., Chan C.H., King A., Williams L., French G.L. Time-kill studies of tea tree oils on clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000;45:639–643. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.5.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarello V., Donadu M.G., Ferrari M., Piga G., Usai D., Zanetti S., Sotgiu M.A. Treatment of acne with a combination of propolis, tea tree oil, and Aloe vera compared to erythromycin cream: two double-blind investigations. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018;10:175–181. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S180474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills O.J., Thornsberry C., Cardin C.W., Smiles K.A., Leyden J.J. Bacterial resistance and therapeutic outcome following three months of topical acne therapy with 2% erythromycin gel versus its vehicle. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2002;82:260–265. doi: 10.1080/000155502320323216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S.H., Roh H.S., Kim Y.H., Kim J.E., Ko J.Y., Ro Y.S. Antibiotic resistance of microbial strains isolated from Korean acne patients. J. Dermatol. 2012;39:833–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M., Kametani I., Higaki S., Yamagishi T. Identification of Propionibacterium acnes by polymerase chain reaction for amplification of 16S ribosomal RNA and lipase genes. Anaerobe. 2003;9:5–10. doi: 10.1016/S1075-9964(03)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neamsuvan O., Kama A., Salaemae A., Leesen S., Waedueramae N. A survey of herbal formulas for skin diseases from Thailand’s three southern border provinces. J. Herb. Med. 2015;5:190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkari T. Comparative chemistry of sebum. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1974;62:257–267. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12676800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omulo S., Thumbi S.M., Njenga M.K., Call D.R. A review of 40 years of enteric antimicrobial resistance research in Eastern Africa: what can be done better? Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2015;4 doi: 10.1186/s13756-014-0041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazyar, N., Yaghoobi, R., Bagherani, N., Kazerouni, A., 2013. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int. J. Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05654.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pineau, R.M., Hanson, S.E., Lyles, J.T., Quave, C.L., 2019. Growth Inhibitory Activity of Callicarpa americana Leaf Extracts Against Cutibacterium acnes . Front. Pharmacol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rafieian-kopaei M. Medicinal plants and the human needs. J. HerbMed Pharmacol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Ross J.I., Eady E.A., Cove J.H., Ratyal A.H., Cunliffe W.J. Resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin in cutaneous propionibacteria is associated with mutations in 23S rRNA. Dermatology. 1998:69–70. doi: 10.1159/000017871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabry N.A., Farid S.F., Dawoud D.M. Antibiotic dispensing in Egyptian community pharmacies: an observational study. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S., Patra P., Mridha K., Ghosh S., Mukhopadhyay A., Thakurta R. Personality disorders and its association with anxiety and depression among patients of severe acne: a cross-sectional study from Eastern India. Indian J. Psychiatr. 2016;58:378–382. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer F., Fich F., Lam M., Gárate C., Wozniak A., Garcia P. Antimicrobial susceptibility and genetic characteristics of Propionibacterium acnes isolated from patients with acne. Int. J. Dermatol. 2013;52:418–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz C.F.P., Kilian M. The natural history of cutaneous propionibacteria, and reclassification of selected species within the genus propionibacterium to the proposed novel genera acidipropionibacterium gen. Nov., cutibacterium gen. nov. and pseudopropionibacterium gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016;66:4422–4432. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Kaur N., Kishore L., Kumar Gupta G. Management of diabetic complications: a chemical constituents based approach. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack R. Antibiotic resistance in the tropics. 2. Some thoughts on the epidemiology and clinical significance of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1989;83:42–44. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90701-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobhy N., Aly F., El Kader O.A., Ghazal A., Elbaradei A. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from skin and soft tissue infections (in a sample of Egyptian population): analysis of mec gene and staphylococcal cassette chromosome. Brazil. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;16:426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totté, J.E.E., van der Feltz, W.T., Bode, L.G.M., van Belkum, A., van Zuuren, E.J., Pasmans, S.G.M.A., 2016. A systematic review and meta-analysis on Staphylococcus aureus carriage in psoriasis, acne and rosacea. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-016-2647-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tuchayi S.M., Makrantonaki E., Ganceviciene R., Dessinioti C., Feldman S.R., Zouboulis C.C. Acne vulgaris. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015;1:15029. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner S., Pryer K.M., Miao V.P.W., Palmer J.D. Investigating deep phylogenetic relationships among cyanobacteria and plastids by small subunit rRNA sequence analysis. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 1999:327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valgas C., De Souza S.M., Smânia E.F.A., Smânia A. Screening methods to determine antibacterial activity of natural products. Brazil. J. Microbiol. 2007;38:369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh B., Michiels J.E., Wenseleers T., Windels E.M., Boer P. Vanden, Kestemont D., De Meester L., Verstrepen K.J., Verstraeten N., Fauvart M., Michiels J. Frequency of antibiotic application drives rapid evolutionary adaptation of Escherichia coli persistence. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:16020. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindel A., Trincado P., Cuevas O., Ballesteros C., Bouza E., Cercenado E. Molecular epidemiology of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Spain: 2004–12. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014;69:2913–2919. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpato D.E., de Souza B.V., Dalla Rosa L.G., Melo L.H., Daudt C.A.S., Deboni L. Use of antibiotics without medical prescription. Brazilian J. Infect. Dis. 2005;9:288–291. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702005000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vora J., Srivastava A., Modi H. Antibacterial and antioxidant strategies for acne treatment through plant extracts. Inform. Med. Unlocked. 2018;13:128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T.R., Efthimiou J., Dreno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016;16:e23–e33. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, P., 2019. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 29th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Clin. Lab. Stand. Institute.

- Williams, P.C.M., Isaacs, D., Berkley, J.A., 2018. Antimicrobial resistance among children in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30467-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zaenglein A.L., Pathy A.L., Schlosser B.J., Alikhan A., Baldwin H.E., Berson D.S., Bowe W.P., Graber E.M., Harper J.C., Kang S., Keri J.E., Leyden J.J., Reynolds R.V., Silverberg N.B., Stein Gold L.F., Tollefson M.M., Weiss J.S., Dolan N.C., Sagan A.A., Stern M., Boyer K.M., Bhushan R. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016;74:945–973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.