Abstract

Denosumab is an antiresorptive drug targeting RANK ligand, currently licensed for postmenopausal and male osteoporosis, bone loss associated with hormone ablation in men with prostate cancer and with systemic glucocorticoid treatment, and also used in oncology for the treatment of bone metastases and unresectable giant cell tumour of bone.

When used for the treatment of osteoporosis or bone loss the drug is usually well-tolerated with non-specific musculoskeletal pain being the most common side effect. However denosumab has been associated with some dermatological manifestations including dermatitis, eczema, pruritus and, less commonly, cellulitis. All these side effects are generally mild and self-limiting.

We hereby report the first documented case of Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) syndrome following denosumab administration.

DRESS syndrome is an extremely rare but potentially life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction.

The syndrome should be considered in patients who present with new rash, eosinophilia and systemic organ dysfunction, especially when associated with new medications. Notably it has been previously reported in patients with osteoporosis treated with strontium ranelate but it has never been linked to any other antiosteoporotic drugs.

Since the clinical manifestations of DRESS syndrome can span over a period of several months the diagnosis can frequently be quite difficult and it can become even more challenging in people taking denosumab and other drugs given in period doses, as both clinicians and patients are less likely to link the symptoms to the medication.

Better recognition of DRESS syndrome is therefore needed, as well as awareness of the possibility of this reaction to occur in patients taking denosumab.

Keywords: DRESS, Denosumab, Osteoporosis, Eosinophilia, Hypersensitivity

1. Introduction

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is a severe and potentially life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction caused by exposure to certain medications (Phillips et al., 2011; Bocquet et al., 1996). It is extremely heterogeneous in its manifestation but has characteristic delayed-onset cutaneous and multi-system features with a protracted natural history. The reaction typically starts with a fever, followed by widespread skin eruption of variable nature. This progresses to inflammation of internal organs such as hepatitis, pneumonitis, myocarditis and nephritis, and haematological abnormalities including eosinophilia and atypical lymphocytosis (Kardaun et al., 2013; Cho et al., 2017).

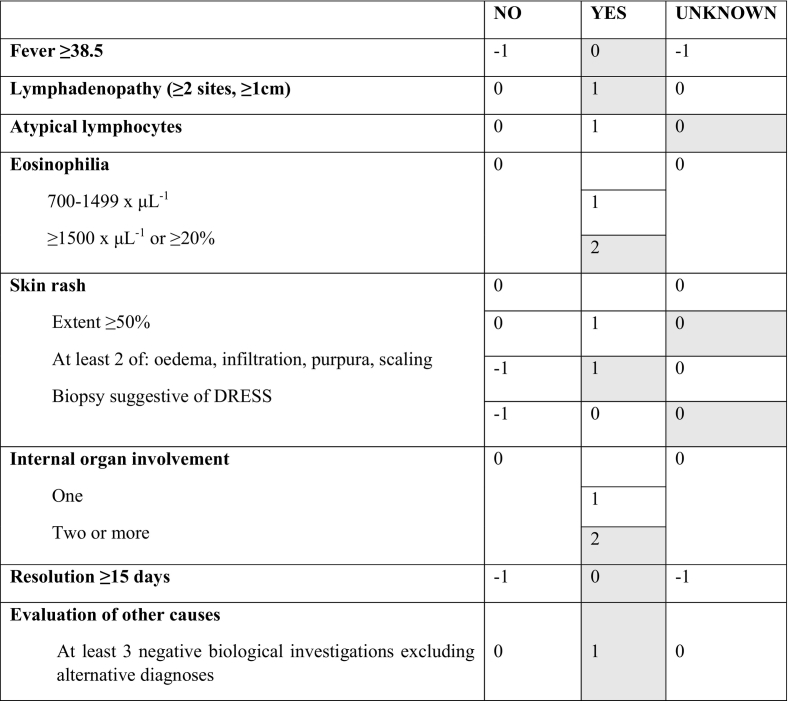

DRESS syndrome is most commonly classified according to the international scoring system developed by the RegiSCAR group (Kardaun et al., 2013). RegiSCAR accurately defines the syndrome by considering the major manifestations, with each feature scored between −1 and 2, and 9 being the maximum total number of points. According to this classification, a score of <2 means no case, 2–3 means possible case, 4–5 means probable case, and 6 or above means definite DRESS syndrome. Table 1 gives an overview of the RegiSCAR scoring system.

Table 1.

RegiSCAR-group scoring system for DRESS syndrome* (criteria fulfilled by the case described are highlighted in grey and give a total score of 7 consistent with ‘definite DRESS syndrome’).

DRESS syndrome usually develops 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to the causative drug, with resolution of symptoms after drug withdrawal in the majority of cases (Husain et al., 2013a). Some patients require supportive treatment with corticosteroids, although there is a lack of evidence surrounding the most effective dose, route and duration of the therapy (Adwan, 2017). Although extremely rare, with an estimated population risk of between 1 and 10 in 10,000 drug exposures, it is significant due to its high mortality rate, at around 10% (Tas and Simonart, 2003; Chen et al., 2010).

The pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome remains largely unknown. Current evidence suggests that patients may be genetically predisposed to this form of hypersensitivity, with a superimposed risk resulting from Human Herpes Virus (HHV) exposure and subsequent immune reactivation (Cho et al., 2017; Husain et al., 2013a). In fact, the serological detection of HHV-6 has even been proposed as an additional diagnostic marker for DRESS syndrome (Shiohara et al., 2007). Other potential risk factors identified are family history (Sullivan and Shear, 2001; Pereira De Silva et al., 2011) and concomitant drug use, particularly antibiotics (Mardivirin et al., 2010). DRESS syndrome appears to occur in patients of any age, with patient demographics from several reviews finding age ranges between 6 and 89 years (Picard et al., 2010; Kano et al., 2015; Cacoub et al., 2013).

DRESS syndrome was first described as an adverse reaction to antiepileptic therapy, but has since been recognised as a complication of an extremely wide range of medications (Adwan, 2017). In rheumatology, it has been classically associated with allopurinol and sulfasalazine, but has also been documented in association with many other drugs including leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, febuxostat and NSAIDs (Adwan, 2017). Recent evidence has also identified a significant risk of DRESS syndrome with strontium ranelate use (Cacoub et al., 2013). Thus far, that is the only anti-osteoporotic drug associated with DRESS syndrome, although there are various cases of other adverse cutaneous reactions linked to anti-osteoporotic medications, ranging from benign maculopapular eruption to Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) (Musette et al., 2010). Denosumab, an antiresorptive RANK ligand (RANKL) inhibitor licensed for osteoporosis, is currently known to be associated with some dermatological manifestations including dermatitis, eczema, pruritus and, less commonly, cellulitis (Prolia, n.d.).

We hereby describe the first documented case of DRESS syndrome associated with denosumab treatment.

2. Case presentation

The patient is a 76-year old female with osteoporosis and a background of alcoholic fatty liver disease and lower limb venous insufficiency. Osteoporosis was first diagnosed in 2003 and treated with risedronate, calcium and vitamin D, until 2006. While on this treatment, the patient sustained T12 and L3 fractures, the latter treated with kyphoplasty, and was therefore deemed a non-responder to risedronate. From December 2007 until June 2009, she was treated with teriparatide, and in July 2009, was switched back to risedronate. She remained on risedronate until May 2015, when a switch to denosumab (60 mg subcutaneous 6-monthly injections) was made due to poor adherence to oral medication, with a plan to review the patient after 12 months.

The first injection was self-administered with no side effects in June 2015. The second injection was administered in December 2015. Ten days later the patient presented to her General Practitioner (GP) with sudden-onset fever, diffuse pruritic erythematous skin rash, facial swelling (Fig. 1) and non-productive cough.

Fig. 1.

Photograph showing facial swelling and erythema following administration of second denosumab injection.

Blood tests requested by the GP revealed marked eosinophilic leucocytosis (WBC 12,200 × μL−1, Eo 5500 × μL−1 [46%]) with otherwise normal FBC and increased IgE levels at 254 IU/mL. Faecal parasites test came back as negative. Notably, FBC checked in May 2015 and November 2015 was normal.

The manifestations were interpreted as an allergic reaction and a course of anti-histamines was prescribed by the GP. When the symptoms did not subside, referral was made to an allergist with special interest in respiratory diseases in February 2016. At physical examination multiple enlarged submandibular and cervical lymph nodes were noted, but no abnormal findings were found on lung auscultation. The patient was also referred to the haematology clinic where no further abnormal findings were reported.

The specialists were unable to formulate a definitive diagnosis and instigated further investigations, including chest X-ray, additional blood tests, lung function tests (LFT), ultrasound scan of the abdomen and blood smear test. Chest X-ray showed no abnormal findings, while LFT revealed mild restrictive changes and severe obstructive changes at distal airways. Ultrasound scan of the abdomen confirmed previous changes consistent with severe fatty liver disease; of note, enlarged hepatic hilar lymph nodes, previously unreported, were also disclosed. Blood tests showed normalisation of WBC count while eosinophilia was confirmed; protein electrophoresis showed hypergammaglobulinemia (21.6 g/dL); ANA were positive (320 Titre Units, speckled pattern) with otherwise negative dsDNA Ab, ENA screen and ANCA, and normal complement levels.

No morphological abnormalities of leucocytes were reported at blood smear test and consequently the patient was discharged from the haematology clinic with a diagnosis of ‘eosinophilia likely of allergic origin’.

Notably, in February 2016 a urinary tract infection was diagnosed and a course of amoxicillin/clavulanate was prescribed.

In May 2016, the patient was admitted to the cardiology ward after presenting to the Emergency Department with chest pain and nausea. In view of increased myocardial enzymes (troponin I 309.2 ng/L, myoglobin 164.5 ng/mL), an acute MI was initially suspected. However, a coronary angiography performed during the admission revealed no abnormalities, making the diagnosis less likely. ECG findings were therefore felt to be consistent with possible pericarditis. Subsequently, a heart MRI scan revealed mild pericardial effusion, but no findings consistent with myocardial damage or dysfunction. Myocardial enzymes normalized within 5 days and eventually a definitive diagnosis of non-specific myopericarditis was made. Unfortunately, 1 week later the patient was moved to the general medicine ward after developing abdominal pain and general malaise. Blood tests showed increased creatinine and urea (creatinine 2.14 mg/dL, BUN 41 mg/dL, eGFR 22 mL/min), increased IgA and IgG gamma-globulins (1202 and 3272 mg/dL, respectively), and eosinophilia (WBC 10750 × μL−1, Eo 3300 × μL−1, 31%). A diagnosis of acute kidney injury (AKI) was made. Again, no cause was identified, but the patient was treated with IV fluids and diuretics with prompt normalisation of creatinine (0.97 mg/dL at discharge). Treatment with amlodipine was prescribed at discharge alongside amiloride/hydrochlorotiazide continuation.

The patient was followed up in the rheumatology clinic in June 2016. She reported progressive improvement of the skin rash over a 6-month period but persistent general malaise and itchy skin. Blood tests still showed raised gamma-globulins, but no eosinophilia; liver function tests and creatinine were normal. At this point, a diagnosis of likely DRESS syndrome due to denosumab was made. Treatment was therefore discontinued and patient was restarted on risedronate. Steroids were not started as the symptoms were deemed mild at that time.

Review was intended for 6 months but the patient was lost at follow-up until July 2017. At this point she was well with no systemic symptoms except persistent fatigue. Blood tests at this point were all back to baseline.

3. Discussion

3.1. Clinical presentation

This is the first documentation of DRESS syndrome in response to denosumab. After initial clinical suspicion, a definite diagnosis of DRESS was confirmed following accurate review of the patient's clinical history and test results, using the RegiSCAR criteria as showed in Table 1.

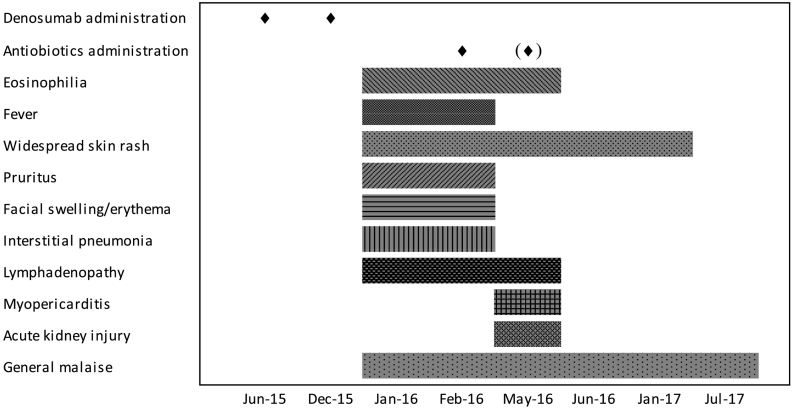

In fact, nearly all of the classical cutaneous and multi-system effects were seen, and the course of the reaction was protracted as is typical of DRESS syndrome, with relapses occurring for weeks at a time over the course of several months (Corneli, 2017). Fig. 2 shows a timeline of clinical features and eosinophils trend over time.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of clinical manifestations and eosinophilia number over time.

A literature search showed several predisposing factors for development of DRESS syndrome. The most commonly cited is HHV-6 infection markers (Cho et al., 2017; Husain et al., 2013a). Unfortunately, we were unable to test this on our patient. Another factor was family history (Sullivan and Shear, 2001) which is uncertain in this patient, although this does not rule out genetic susceptibility (Sullivan and Shear, 2001). It is most interesting to note that concomitant drugs have been reported to be an aggravating factor in the development of DRESS (Sullivan and Shear, 2001; Pereira De Silva et al., 2011), in particular amoxicillin (Mardivirin et al., 2010). The mechanism of this is not fully understood. The patient was administered antibiotic treatment in February 2016 and also possibly in May 2016. This could have contributed to sustain and perpetuate the clinical manifestations of the reaction. This can be seen in Fig. 2 which shows the timeline of manifestations in relation to denosumab administration and subsequent antibiotic use.

An unusual feature of this presentation was the hypergammaglobulinaemia that was detected several times, on admission and on follow-up in rheumatology outpatient clinic. Conversely, hypogammaglobulinaemia has been previously significantly associated with DRESS, the mechanism of which is not fully understood (Boccara et al., n.d.).

Denosumab was identified as the cause of the reaction through a process of elimination as described by the RegiSCAR group (Kardaun et al., 2013). In our clinical case, denosumab was the only drug newly initiated, with the patient's other medications (lactulose and amiloride/hydrochlorotiazide) both taken long term with no adverse cutaneous effects; DRESS onset, however, occurred 10 days after the second injection of denosumab.

DRESS syndrome is a delayed allergic response to drugs, which are generally administered for several days before DRESS onset (e.g. antibiotics or allopurinol) (Agier et al., 2016). In the case of denosumab, due to its long half-life, the second administration of the drug is scheduled after 6 months. It is therefore possible to hypothesise that such a delayed reaction may be observed not after the first injection but after a following one.

Alternative diagnoses were also considered, such as ANCA–negative granulomatous poliangiitis with eosinophilia being this subset of patients more likely to have heart involvement without asthma or rhino-sinusitis (Sokolowska et al., 2014; Comarmond et al., 2013). However, no evidence of necrotizing vasculitis was found and this diagnosis was therefore ruled out. Similarly, a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus was excluded as patients with this connective tissue disease usually show complement consumption when kidney or heart are involved and, also, the clinical picture tends to worsen without steroid therapy.

3.2. Denosumab

Denosumab is the first product developed to reduce bone resorption by inhibiting RANKL binding to RANK and was initially approved in 2010 for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men at increased risk of fractures. It is currently also licensed for fracture prevention in bone loss secondary to hormone ablation in men with prostate cancer and systemic glucocorticoid treatment, and used in oncology for the treatment of bone metastases and unresectable giant cell tumour of bone (Prolia, n.d.; Green, 2010). Data drawn from phase II and III clinical trials, as well as post-marketing surveillance, have shown that denosumab when used for treating osteoporosis and bone loss is relatively safe, with few associated risks (Prolia, n.d.; Watts et al., 2012). Cutaneous side effects originally reported in a randomized controlled study were eczema and rash, and uncommonly, cellulitis. However, a subsequent analysis found the incidence of cellulitis to be not significantly increased (Ronceray et al., 2012).

Most cases of DRESS syndrome have been reported from oral medications with daily doses (Kardaun et al., 2013; Pereira De Silva et al., 2011). This case appears to be unique in the literature, having resulted from a one-off subcutaneous administration. With regards to route of administration, we found one case of DRESS as a reaction to subcutaneous enoxaparin, but in this case the drug was administered daily for 15 days before onset of the reaction (Chen et al., 2013).

The characteristic delayed onset of DRESS syndrome may be due to the incubation period needed for sensitisation to the offending drug (Husain et al., 2013b) or possibly due to the time taken for reactivation of host viruses implicated in the pathogenesis of the reaction (Corneli, 2017). Ten days is a relatively rapid onset compared to average delay in onset of DRESS (Kardaun et al., 2013). Interestingly, trials have shown that peak concentrations of denosumab are detected in the serum in an average of 10 days (Chen et al., 2013). However, the reaction followed the second denosumab subcutaneous injection and therefore occurred around 6 months after the first exposure to the medication.

It is also worth noting that the mainstay of DRESS management is removal of the offending drug, which leads to an average recovery time of 6–9 weeks [5,36]. However, due to the distinctively long half-life of denosumab, this was not possible. The average half-life of denosumab is 26 days, with subsequent decline occurring over a period of four to 5 months (Chen et al., 2013). Thus, the patient will have been continuously exposed to the drug over this period of time, as though she were continuing to take the medication. This, along with concomitant antibiotic use, may explain why the patient had such a prolonged reaction with several peaks in her presentation, initially presenting with rash, fever and pneumonitis, later with myopericarditis, and after that again with AKI.

4. Conclusion

DRESS syndrome should be considered when a patient presents with a sudden onset widespread rash, eosinophilia, and a multitude of new systemic organ dysfunction of unexplained aetiology.

This patient was assessed by several physicians for many different clinical manifestations, but DRESS was not recognised or linked to the denosumab administration until 6 months later. This implies that better recognition of DRESS syndrome is needed, as well as awareness of the possibility of this reaction in patients taking denosumab.

The characteristically delayed onset of DRESS syndrome means that the culprit drug is often difficult to identify. This is particularly difficult when patients have multiple existing co-morbidities and medications. Patients should be made aware of this rare reaction following denosumab in order to facilitate a quicker consideration of the culprit drug and improve the diagnosis of DRESS.

This is of particular significance when prescribing denosumab and other anti-osteoporotic drugs given in periodic doses or infusions, as both patients and clinicians are less likely to link the development of symptoms to one dose of medication taken up to 6 weeks previously. Thus, this case highlights new therapeutic considerations for prescription of anti-osteoporotic medications, and in particular, denosumab.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' credit roles

Mariam Al-Attar: Writing - original draft.

Maria De Santis: Resources; Data curation.

Marco Massarotti: Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing - review & editing.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated this article can be found, in online version.

References

- Adwan M.H. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome and the rheumatologist. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2017;19:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11926-017-0626-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agier M.S., Boivin N., Maruani A., Giraudeau B., Gouraud A., Haramburu F., Jean Pastor M.J., Machet L., Jonville-Bera A.P. Risk assessment of drug-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: a disproportionality analysis using the French Pharmacovigilance database. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016;175:1067–1069. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O. Boccara, L. Valeyrie-Allanore, B. Crickx, V. Descamps, Association of hypogammaglobulinemia with DRESS (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms)., Eur. J. Dermatol. 16 (n.d..) 666–8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17229608 (accessed January 30, 2018). [PubMed]

- Bocquet H., Bagot M., Roujeau J.C. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma and drug hypersensitivity syndrome (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: DRESS) Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 1996;15:250–257. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(96)80038-1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9069593 (accessed December 4, 2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacoub P., Descamps V., Meyer O., Speirs C., Belissa-Mathiot P., Musette P. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) in patients receiving strontium ranelate. Osteoporos. Int. 2013;24:1751–1757. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-C., Chiu H.-C., Chu C.-Y. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Arch. Dermatol. 2010;146:1373. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-C., Cho Y.-T., Chang C.-Y., Chu C.-Y. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: A drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome with variable clinical features. Dermatologica Sin. 2013;31:196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y.T., Yang C.W., Chu C.Y. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an interplay among drugs, viruses, and immune system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18061243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comarmond C., Pagnoux C., Khellaf M., Cordier J.F., Hamidou M., Viallard J.F., Maurier F., Jouneau S., Bienvenu B., Puéchal X., Aumaître O., Le Guenno G., Le Quellec A., Cevallos R., Fain O., Godeau B., Seror R., Dunogué B., Mahr A., Guilpain P., Cohen P., Aouba A., Mouthon L., Guillevin L., French Vasculitis Study Group Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): clinical characteristics and long-term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):270–281. doi: 10.1002/art.37721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneli H.M. DRESS syndrome: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Pediatr. Emerg. Care. 2017;33:499–502. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green W. Denosumab (Prolia) Injection A New Approach to the Treatment of Women With Postmenopausal Osteoporosis, Drug. Forecast. 2010;35:553–559. [Google Scholar]

- Husain Z., Reddy B.Y., Schwartz R.A. DRESS syndrome: part I. clinical perspectives. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1–693.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain Z., Reddy B.Y., Schwartz R.A. DRESS syndrome. Part II. Management and therapeutics., J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013;68:709.e1–709.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano Y., Tohyama M., Aihara M., Matsukura S., Watanabe H., Sueki H., Iijima M., Morita E., Niihara H., Asada H., Kabashima K., Azukizawa H., Hashizume H., Nagao K., Takahashi H., Abe R., Sotozono C., Kurosawa M., Aoyama Y., Chu C.-Y., Chung W.-H., Shiohara T. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian research committee on severe cutaneous adverse reactions (ASCAR) J. Dermatol. 2015;42:276–282. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardaun S.H., Sekula P., Valeyrie-Allanore L., Liss Y., Chu C.Y., Creamer D., Sidoroff A., Naldi L., Mockenhaupt M., Roujeau J.C. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013;169:1071–1080. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardivirin L., Valeyrie-Allanore L., Branlant-Redon E., Beneton N., Jidar K., Barbaud A., Crickx B., Ranger-Rogez S., Descamps V. Amoxicillin-induced flare in patients with DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms): report of seven cases and demonstration of a direct effect of amoxicillin on human Herpesvirus 6 replication in vitro. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2010;20:68–73. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musette P., Brandi M.L., Cacoub P., Kaufman J.M., Rizzoli R., Reginster J.Y. Treatment of osteoporosis: recognizing and managing cutaneous adverse reactions and drug-induced hypersensitivity. Osteoporos. Int. 2010;21:723–732. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira De Silva N., Piquioni P., Kochen S., Saidon P. Risk factors associated with DRESS syndrome produced by aromatic and non-aromatic antipiletic drugs. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011;67:463–470. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips E.J., Chung W.-H., Mockenhaupt M., Roujeau J.-C., Mallal S.A. Drug hypersensitivity: Pharmacogenetics and clinical syndromes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011;127:S60–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard D., Janela B., Descamps V., D’Incan M., Courville P., Jacquot S., Rogez S., Mardivirin L., Moins-Teisserenc H., Toubert A., Benichou J., Joly P., Musette P. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a multiorgan antiviral T cell response. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010;2 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prolia - Summary of product characteristics (SmPC) - (eMC), (n.d.). https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/568 (last updated on eMC June 8, 2018).

- Ronceray S., Dinulescu M., Le Gall F., Polard E., Dupuy A., Adamski H. Enoxaparin-Induced DRESS Syndrome. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2012;4:233–237. doi: 10.1159/000345096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiohara T., Iijima M., Ikezawa Z., Hashimoto K. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007;156:1083–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowska B.M., Szczeklik W.K., Wludarczyk A.A., Kuczia P.P., Jakiela B.A., Gasior J.A., Bartyzel S.R., Rewerski P.A., Musial J. ANCA-positive and ANCA-negative phenotypes of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA): outcome and long-term follow-up of 50 patients from a single polish center. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2014;32(3 Suppl 82):S41–S47. May-Jun. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan J.R., Shear N.H. The drug hypersensitivity syndrome: what is the pathogenesis? Arch. Dermatol. 2001;137:357–364. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11255340 (accessed January 31, 2018) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tas S., Simonart T. Management of Drug Rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353–356. doi: 10.1159/000069956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts N.B., Roux C., Modlin J.F., Brown J.P., Daniels A., Jackson S., Smith S., Zack D.J., Zhou L., Grauer A., Ferrari S. Infections in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with denosumab or placebo: Coincidence or causal association? Osteoporos. Int. 2012;23:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1755-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.