Abstract

Two pairs of species-specific PCR primers targeting the housekeeping groEL gene, Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, were designed to quantify human oral and fecal Streptococcus parasanguinis. Blast analysis against reference sequences of NCBI nucleotide collection database and the Chaperonin Sequence Database showed the forward primers Spa146f and Spa93f 100% matched only with S. parasanguinis, and the in silico Simulated PCR algorithm showed both primer pairs hit only S. parasanguinis groEL gene in Chaperonin Sequence Database. The two primer pairs were respectively used to perform PCR with saliva DNA of each of 6 human subjects, and the amplicons of individual PCR reactions were cloned. The phylogenetic analysis showed cloned sequences were all affiliated to S. parasanguinis, which further validates the specificity of two primer pairs, and that individual subjects harbored multiple genotypes of S. parasanguinis in saliva. By spiking S. parasanguinis into human fecal samples, we found the quantification limit of quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assays for both primer pairs was 5–6 log10 groEL copies/g feces. Human fecal S. parasanguinis amounts quantified with qPCR using each of the two primer pairs correlated well with those determined with metagenomic sequencing. qPCR with either primer pair showed periodontitis patients had significantly lower level of saliva S. parasanguinis than healthy people. In both feces and saliva, the S. parasanguinis abundances quantified with two primer pairs exhibited strong and significant correlation. Our results show that the two S. parasanguinis-specific primer pairs can be used to quantify and profile human saliva and fecal S. parasanguinis.

Keywords: Streptococcus parasanguinis, quantitative PCR, groEL gene, feces, saliva

Introduction

Streptococcus parasanguinis is a common human commensal bacterial species colonizing multiple body sites. It is a prevalent bacteria in the oral cavity of both adults and infants (Franzosa et al., 2014; Dzidic et al., 2018), and plays an important role in dental plaque formation (Garnett et al., 2012) and significantly inhibits the growth the periodontopathogens by producing hydrogen peroxide (Herrero et al., 2016). The abundance of oral S. parasanguinis is associated with childhood allergies (Dzidic et al., 2018) and caries (Becker et al., 2002). S. parasanguinis is also frequently isolated from the breast milk of women (Lara-Villoslada et al., 2007), and our human breast milk microbiota-associated mouse model showed that breast milk S. parasanguinis can colonize gut (Wang et al., 2017). Indeed, S. parasanguinis is one of the dominating pioneer colonizers of human infant intestine in first days of life (Songjinda et al., 2005), a predominant bacterial species in the small intestine of adults (van den Bogert et al., 2013b), and also detected in the feces of children (Zhang et al., 2015) and adults (Franzosa et al., 2014). In vitro experiments showed one human small intestinal S. parasanguinis strain moderately activated NF-κB via TLR2/6 signaling, and thus induced the maturation, activation and cytokine IL12 secretion of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (van den Bogert et al., 2014). Occasionally, S. parasanguinis can translocate to the bloodstream and result in infective endocarditis (Naveen Kumar et al., 2014). Therefore, it is necessary to develop molecular methods to quantify and profile S. parasanguinis in human microbiome samples to understand its role in human health and diseases.

16S rRNA gene is often used to identify bacteria at the species level, but the interspecies divergence of Streptococcus 16S rRNA gene as low as 0.3% does not allow the effective discrimination of closely related Streptococci (Glazunova et al., 2009). Van den Bogert et al. (2013a) identified unique genes that are solely present in the genome of one S. parasanguinis strain isolated from the ileostoma effluent of one healthy Ileostomist, and designed specific PCR primers for the strain, but the primers cannot detect S. parasanguinis strains colonizing other human subjects. Park and Kook (2013) developed S. parasanguinis-specific PCR primers based on the genomic DNA sequences with unknown function, however, it is unknown whether the unannotated genomic sequences are present in all strains of S. parasanguinis.

The housekeeping groEL gene is ubiquitously distributed among bacteria. It encodes chaperonin GroEL (synonyms are Cpn60 and Hsp60) that assists proper protein folding in bacterial cells. The groEL gene sequences are widely used to study the phylogeny of bacteria (Viale et al., 1994) including Streptococcus spp. (Teng et al., 2002; Glazunova et al., 2009; Lourenco et al., 2017; Leigh et al., 2018). In addition, groEL gene shows 3.4% divergence among different Streptococcus species, and thus has much higher power than 16S rRNA gene in discriminating Streptococcus species (Glazunova et al., 2009). The Chaperonin Sequence Database1 (Junick and Blaut, 2012) currently contains ∼22,000 groEL sequences of prokaryotes, eukaryotes, and archaea, and among these sequences, 866 are from 64 Streptococcus species, and 8 are from 7 S. parasanguinis strains. This database provides good reference sequences of groEL gene for PCR primer development.

In the present study, we developed two PCR primer pairs, which consist of three primers, to specifically detect human commensal S. parasanguinis. Both primer pairs were used to amplify and clone the groEL gene of human saliva S. parasanguinis, and quantify human fecal and saliva S. parasanguinis with quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR).

Materials and Methods

Design of groEL Gene-Targeted S. parasanguinis-Specific Primers

The groEL sequences of S. parasanguinis strains and closely related Streptococcus species (Glazunova et al., 2009) were downloaded from the Chaperonin Sequence Database in March 20171 and subjected to a multiple alignment with ClustalX version 2.1 provided by the European Bioinformatics Institute2. The region of 552 bp of the complete groEL gene named universal target (UT) sequences was used to manually identify the discriminative nucleotides. Three primers, two forward primers Spa146f and Spa93f, and one reverse primer Spa525r were designed, and they composed two primer pairs, Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Two S. parasanguinis-specific primer pairs based on the groEL genea.

| Primer Pair | Sequence (5′ to 3′)b | Product size/bp |

| Spa146f/Spa525r | AACAATGCGATYCCAGTATCRAG/CTACGACATTAAAGGTACCDCGG | 424 |

| Spa93f/Spa525r | TCCGYCGTGGGATTGAGACC/CTACGACATTAAAGGTACCDCGG | 474 |

aThe two primer pairs consist of three primers, two forward primers Spa146f and Spa93f, and one reverse primer Spa525r. bIUPAC ambiguity codes: R (A or G), Y (C or T), D (G or A or T).

The genomes of 30 S. parasanguinis strains deposited in the NCBI genome collection database3 were downloaded. The sequence of each designed primer was blast against the 30 S. parasanguinis genomes using NCBI Basic local alignment search tool4. Each primer was also blast against all the groEL gene sequences of the Chaperonin Sequence Database1 online with the “Primer Blast” program, and then against all sequences in NCBI nucleotide collection (nr/nt) database with the blastn tool4.

Simulated PCR (SPCR)

Eight hundred and sixty six groEL universal target (UT) sequences of 64 Streptococcus spp., which included 8 sequences of 7 S. parasanguinis strains, were downloaded from the Chaperonin Sequence Database1 as templates. The sequences of these templates and each of the two primer pairs, Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, were introduced into SPCR (Cao et al., 2005). The product amplification coefficient, increase of which corresponds to the enhancement of the annealing temperature in experimental PCR, was set to 0.80 (the recommended value according to the SPCR developer) and 0.90, respectively, for individual primer pair, and the SPCR algorithm output the template sequences that can be amplified by the tested primer pair under each coefficient.

Bacterial Strains and Human Subjects

Strains S. parasanguinis F278 and S. salivariusF286 were previously isolated from human breast milk in our laboratory, and the accession numbers of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of the two strains were KY038191 and KY038192, respectively (Wang et al., 2017). S. sanguinis ATCC 10556, S. mutans UA159 and S. gordonii ATCC 10558 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All strains were cultured in liquid M17 medium (Hopebiol, Qingdao, China) in an anaerobic chamber (DG500, Don Whitley Scientific, United Kingdom) at 37°C for 10 h.

The feces of 22 Chinese children, which contained varied abundance ofS. parasanguinis according to our previous metagenomic sequencing (Zhang et al., 2015) were used in the present study. These 3 to 6-year-old children were diagnosed with Prader–Willi syndrome or simple obesity, and were recruited previously to study the role of gut microbiota in genetic and simple obesity (Zhang et al., 2015). The cohort study was performed under the approval of the Ethics Committee of the School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. 2012-016). Written informed consents were obtained from the guardians of the children.

The saliva DNA of 28 newly diagnosed periodontitis patients and 26 periodontally healthy volunteers, which were stored at −80°C after extraction (Chen et al., 2015), were used in the present study. The periodontitis patients aging 29–67 years and the periodontally healthy volunteers aging 21–55 years were all Chinese Han people, and recruited previously to compare the oral microbiota composition by doing illumina sequencing of 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 region (Chen et al., 2015). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine, China (Document No. 201262). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

DNA Extraction From Bacterial Cultures and Human Feces

Genomic DNA from the bacterial cultures was extracted as described previously (Wang et al., 2017). DNA extraction from fecal samples was conducted as previously described (Godon et al., 1997). Both exaction processes included chemical lysis and bead beating to break the bacterial cells. The integrity of the DNA was assessed by using 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis gels stained with ethidium bromide, and the concentration was quantified with PicoGreen fluorescent dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, United States) by using SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Francisco, CA, United States).

PCR Amplification With Genomic DNA of Bacterial Strains

The two designed primer pairs, Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, were respectively used to do experimental PCR under gradient annealing temperatures using the genomic DNA of S. parasanguinis F278, S. salivarius F286, S. sanguinis ATCC 10556, S. mutans UA159 and S. gordonii ATCC 10558, respectively, as template. The PCR program included an initial denaturing step of 5 min at 94°C, 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, a certain annealing temperature between 58 and 63°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 45 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Each 25 μl PCR mixture contained 1 × PCR buffer, 2mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 0.25 μM of each primer, 0.2 U Taq polymerase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and 20 ng of template DNA. Amplifications were performed with the ABI PCR thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, United States). PCR products were assessed by electrophoresis on 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel.

PCR Amplification and Cloning of S. parasanguinis groEL Gene From Human Saliva and Phylogenetic Analysis of Cloned Sequences

PCR was performed with primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, respectively, using the saliva DNA of each of six human volunteers as template. The 25 μl PCR mixture contained 1 × PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 0.25 μM of each primer, 0.2 U Taq polymerase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and 2 μl saliva DNA. The PCR program was as follows: 94°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 61°C and 62°C for Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, respectively, for 20 s, and 72°C for 45 s; and finally 72°C for 7 min. The size and specificity of PCR products were checked by electrophoresis on 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel.

The products of individual PCR reactions were excised from the 1.5% agarose gel and purified using the Gel Extraction Kit 200 (Omega, United States) as recommended by the manufacturer. Purified amplicons were ligated into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, United States), and then transformed into competent E. coli DH5α cells. From each library, 15 recombinant clones were randomly selected and sequenced (Life Technologies, Shanghai, China).

The cloned sequences were blast against the nr database of GenBank using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST)5 to determine the closest relative bacteria species. The cloned sequences and the reference groEL gene of Streptococcus spp. were aligned, and the reference gene sequences were trimmed to the same length of clone sequences. Neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees containing the cloned sequences and the trimmed groEL gene of Streptococcus spp. were constructed with the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis package 7 (MEGA 7) using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method. The phylogenetic robustness was assessed by bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR of S. parasanguinis in Human Feces and Saliva

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed with primer pair Spa93f-Spa525r and Spa146f-Spa525r, respectively, for each human fecal or saliva sample. The PCR was done in 96-well optical plates on LightCycler® 96 Real-Time PCR System sequence detector (Roche, United States). The 20-μl reaction mixture contained 1 × FastStart SYBR green I PCR Mix (iQTM SYBR® Green, Bio-Rad, United States), 0.5 μM of each primer, and 2 μl fecal/saliva DNA template. The PCR program was as follows: 94°C for 5 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 61°C and 62°C for Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, respectively, for 20 s, 72°C for 45 s, and melting temp 82°C for 5 s for fluorescence detection. To confirm the specificity of the PCR reaction, melting curve analysis was performed after amplification by increasing the temperature at a rate of 0.2°C per second from 65°C to 97°C with continuous fluorescence measurement. PCR reactions were performed in triplicate. Two recombinant plasmids, SH3-7-146f and SH3-9-93f, which were picked from the clone libraries of the S. parasanguinis groEL gene of human saliva, were used to construct the standard curve for the qPCR with primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, respectively. The S. parasanguinis groEL gene copy number was quantified using standard curves constructed from known concentrations of the plasmid DNA ranging from 5 × 101 to 5 × 108 copies/μl. The abundance of S. parasanguinis was expressed as copies/ng DNA.

Spiking Experiments

To determine the quantitative limit of the qPCR with the primer pairs, three fecal samples, which was collected from three obese children respectively and contained no S. parasanguinis according to metagenomic sequencing (Zhang et al., 2015), were used in the spiking experiments. Aliquots of 200 mg feces were spiked with 10-fold serial dilutions of the culture of S. parasanguinis F278 strain ranging from 2 to 9 log10 cells. The concentrations of S. parasanguinis in the spiked samples were numerated by plate counting on M17 agar medium in triplicate. DNA was extracted from spiked feces as described above.

Statistics

Data statistics was done with GraphPad Prism version 6.0. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normal distribution of the data. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the abundances of saliva S. parasanguinis between periodontitis patients and orally healthy people. The Pearson’s correlation test was used to examine the correlation of S. parasanguinis abundances in fecal or saliva quantified with different techniques.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The partial groEL gene sequences of S. parasanguinis cloned from human saliva were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MK608386 – MK608559, MK616660 – MK616661 and MK637615 – MK637617.

Results

Primer Specificity

Primer Spa146f, Spa93f, and Spa525r showed 100% similarity with the groEL gene of all 7 S. parasanguinis strains deposited in Chaperonin Sequence Database6 (Table 2 and Supplementary Tables S1–S3). Besides, we downloaded the genome sequences of 30 S. parasanguinis strains from NCBI genome database7, and compared the primer sequences to the groEL gene sequence of each of the 30 S. parasanguinis strains. Spa146f 100% matched with 28 of 30 S. parasanguinis strains, and showed one base mismatch with 2 strains in the middle position closer to 5′ terminal where the mismatches had no significant effect on PCR amplification (Kwok et al., 1990). Spa93f fully matched with 18 of 30 S. parasanguinis strains, and had one base mismatch with three strains in the middle position or 5′ end, and had one base mismatch with nine strains at 3′ terminal. Spa525r 100% matched with 27 S. parasanguinis strains, and had one base mismatch with three strains in the middle position close to 5′ terminal (Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

TABLE 2.

The sequence alignment of the S. parasanguinis-specific primers with the groEL gene of strains of Streptococcus spp.

| Species | Strains | Spa146f (5′ - 3′) | Spa93f (5′ - 3′) | Spa525r(5′ - 3′) |

| AACAATGCGATYCCAGTATCRAG | TCCGYCGTGGGATTGAGACC | CTACGACATTAAAGGTACCDCGG | ||

| S. parasanguinis | ATCC 15912 | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | •••••••••••••••••••• | ••••••••••••••••••••••• |

| ATCC 903 | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | •••••••••••••••••••• | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | |

| FW213 | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | •••••••••••••••••••• | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | |

| M44 | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | •••••••••••••••••••• | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | |

| M688 | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | •••••••••••••••••••• | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | |

| F0405 | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | •••••••••••••••••••• | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | |

| SK236 | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | •••••••••••••••••••• | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | |

| S. australis | ATCC 700641 | •• T ••C••C•••••••• TG • C • A | •••••••••••••••• AG • A | •••••••••• G •• A •• T ••••• A |

| M624 | •• T ••C••C•••••••• TG • C • A | •••••••••••••••• AG • A | •••••••••• G ••••• T ••••• A | |

| S. infantis | ATCC 700779 | •••••••• A •••••••• T •• T • A | •••••••••••••••• A •• T | • A •• T •• G •• G •• A •• C ••••• A |

| SK1076 | •••••••• T ••••• T •• TG • C • A | •••••••••••••••• AG • A | • A •• T •• G •• G •• A •• C ••••• A | |

| S. oralis | ATCC 35037 | •••••••• C •••••T•• TG • C • A | •••••••••••••••• AG • A | •••••••••• G ••••• T ••••• A |

| ATCC 49296 | •••••••• C •••••T•• TG • C • A | • T •••••••••••••• AG • T | •••• T •• G •• G ••••• T ••••• A | |

| CIP 105158 | •T• GCC ••A• AG ••• TGT • A •• A | •••••G•• ACCT •• A • TGT • | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | |

| CIP 104985 | • T • GCC ••A• AG ••• TGT •A•• A | •••••G•• ACCT •• A • TGT • | ••••••••••••••••••••••• | |

| S. oligofermentans | AS 1.3089 | G •••C•••••••••G•• T •• T • A | •••••••C•••••••• AG • A | • C •• T ••••• G ••••••••••• A |

| S. pneumoniae | ATCC 33400 | •••••C••C••••• T •• TG • C • A | • T •••••••••••••• A •• A | •••• T •• G •• G ••••• T ••••• A |

| ATCC 27336 | •••••C••C••••• T •• TG • C • A | • T •••••••••••••• A •• A | •••• T •• G •• G ••••• T ••••• A | |

| S. pseudopneumoniae | SK674 | •••••C••C••••• T •• TG • C • A | • T •••••••••••••• AG • A | •••• T •• G •••••••• T ••••• A |

| ATCC BAA-960 | •••••C••C••••• T •• TG • C • A | • T •••••••••••••• AG • A | •••• T •• G •••••••• T ••••• A | |

| S. mitis | ATCC 9811 | •••••••• T ••••• T •• TG • C • A | • T •••••••••••••• A •• A | •••• C •• G •• G ••••• T ••••• A |

| ATCC 49456 | •••••••• C ••••• T•• TG • C • A | • T •••••••••••••• AG • A | • C •• C ••••• G ••••• T ••••• A | |

| S. acidominimus | NCTC11291 | GCG •T•T• ACA ••• G •• T •• TG • | • T •••••••• T ••••• AG • A | • A •••••••• G •• A •••••••• A |

| S. suis | BM407 | GCAC •A••A• G ••• T ••••• C• A | • T ••••• C •••••••• AG •• | • A •• A •• G •• G •• T •••••••• A |

| SC84 | GCAC •A••A• G ••• T ••••• C• A | • T ••••• C •••••••• AG •• | • A •• A •• G •• G •• T •••••••• A | |

| S. massiliensis | M212 | • C ••• CAGTG ••••C•• T •• AG • | • T ••••• C •••••••• AG • A | •••••••••• G •• A •• T •••••• |

| 4401825 | • C ••• CAGTG ••••C•• T •• AG • | • T ••••• C •••••••• AG • A | •••••••••• G •• A •• T •••••• | |

| S. sanguinis | ATCC 29667 | TCT ••CT• AG ••••••• T •• T • A | ••••••• C •••••••• AG • A | •••••••••••••••• T ••••• A |

| ATCC 10556 | TCT ••CT• AG ••••••• T •• T • A | ••••••• C •••••••• AG • A | •••••••••••••••• T ••••• A | |

| S. gordonii | ATCC 10558 | G • A • C •••T••••••••T•• T • A | •••••••••••••••• AG • A | •••• A •• G •• G •• A •• T ••••• A |

| M437 | G • A • C •••T••••••••T•• T • A | •••••••••••••••• AG • A | •••• A •• G •• G •• A •• C ••••• A | |

| S. salivarius | ATCC 7073 | GCT •T••• ACA •••••• TG • T • A | •••••••••••••••• AG • A | • A •••••••• G •• A •• T ••••• A |

| JIM8777 | GC ••T••• TCA •••••• TG • T • A | •••••••••••••••• AG • A | • A •• A ••••• G •• A •• T ••••• A | |

| S. alactolyticus | CIP 103244 | • T • GTC • TA • AG ••• TGC • T •• A | •••• TG •• ACCT •• A • TGT • | ••••••••••••••••••••••• |

| ATCC 43077 | TCA • T ••• ACAA ••••• TG • T • A | • T ••••• C •• T •• C •• AT • T | ••••••••••••••••••••••• |

Meanwhile, the sequences of the three primers were compared to the groEL gene of Streptococcus species other than S. parasanguinis (Table 2). The two forward primers, Spa146f and Spa93f, showed multiple mismatches with the sequences of non-S. parasanguinis strains within the last five bases at the 3′ terminal of the primer where the mismatches significantly prevent the amplification of non-specific sequences (Kwok et al., 1990). The reverse primer, Spa525r, 100% matched with the groEL gene of two (but not all) S. oralis strains and two S. alactolyticus strains, but had multiple mismatches with other non-S. parasanguinis strains.

The three primers were respectively blast against the groEL gene sequences of the Chaperonin Sequence Database6 using the Primer Blast tool of the database, and this tool calculated the score value by taking into account of identical bases and gaps of two aligned sequences to reflects the identity of the primer sequence with reference sequences (Altschul et al., 1990). The higher the score is, the more identical the primer is with the reference sequence. The two forward primers, Spa146f and Spa93f, had highest score (46 and 40, respectively) with only S. parasanguinis, and showed significantly lower scores (no higher than 32 and 34, respectively) with non-S. parasanguinis bacteria. The reverse primer, Spa525r, had the highest score 46 with S. parasanguinis strains and two S. alactolyticus strains, and lower scores (no higher than 44) with other bacterial strains.

Each of the three primers was then subjected to online BLAST analysis against the DNA sequences of the NCBI nucleotide collection (nr/nt) database with the NCBI blastn tool, and the alignment score values were also given to evaluate the identity of the primer sequence with the reference sequences. In accordance with the results of Primer Blast in Chaperonin Sequence Database, Spa146f and Spa93f had highest score (46.1 and 40.1, respectively) with only S. parasanguinis but significantly lower scores (no higher than 36.2 for both primers) with non-S. parasanguinis bacteria; and Spa525r had the highest score 46.1 with S. parasanguinis strains, two S. alactolyticus strains, and two S. oralis strains, and showed much lower scores (no higher than 38.2) with other non-S. parasanguinis strains.

The SPCR algorithm predicts in silico whether individual pairs of PCR primers produce amplicons with template DNA sequences at certain product amplification coefficient, increase of which corresponds to the increase of annealing temperature of actual PCR (Cao et al., 2005). The 866 groEL gene sequences of 64 Streptococcus species, including the 8 sequences of 7 S. parasanguinis strains, were downloaded from the Chaperonin Sequence Database, and input as templates into SPCR algorithm. According to the prediction of SPCR, Spa146f-Spa525r amplified only S. parasanguinis sequences at the product amplification coefficient 0.8, while Spa93f-Spa525r did so only when the product amplification coefficient was increased to 0.9 (Supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Figure S1). This suggests that the both primer pairs are capable to specifically amplify the groEL gene of S. parasanguinis under PCR conditions stringent enough, and that compared to Spa93f-Spa525r, Spa146f-Spa525r requires less stringent condition to achieve specific amplification.

Actual PCR was performed using each of the two primer pairs and the genomic DNA of strains belonging to S. parasanguinis, and S. salivarius, S. sanguinis, S. mutans, and S. gordonii that are common human commensal streptococci. Spa146f-Spa525r yielded amplicons of the expected size only for S. parasanguinis at annealing temperature 58 – 63°C, whereas Spa93f-Spa525r did so at annealing temperatures no less than 62°C (Supplementary Figures S2, S3). Spa93f-Spa525r produced an amplicon with the genomic DNA of S. salivarius as templates at annealing temperature 59 – 62°C, but it was about 100 bp smaller in size than S. parasanguinis amplicon (Supplementary Figure S3). The lower annealing temperature of Spa146f-Spa525r compared to Spa93f-Spa525r for specific amplification of S. parasanguinis under the conventional PCR condition is in accordance with the SPCR prediction. However, Spa93f-Spa525r did not generate any amplicon with the S. salivarius genomic DNA as templates in qPCR assays in which the annealing temperature was 62°C (Supplementary Figure S4).

PCR-Cloning of the S. parasanguinis groEL Gene in Human Saliva Samples With the Primer Pairs Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r

In order to further evaluate the specificity of the two primer pairs, we constructed clone libraries with PCR products amplified from the saliva DNA with primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, respectively, for each of 6 people (Supplementary Figure S5). Saliva samples were used because they were reported to harbor diverse and abundant Streptococcus spp. (Sakamoto et al., 2000; Belstrom et al., 2017).

Fifteen clones were randomly selected from each library and sequenced. The Blastn analysis against the DNA sequences of the nucleotide collection (nr/nt) database of NCBI showed that the nearest neighbor bacteria of all the sequenced clones obtained with Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r were S. parasanguinis, with the similarity being 95–100%.

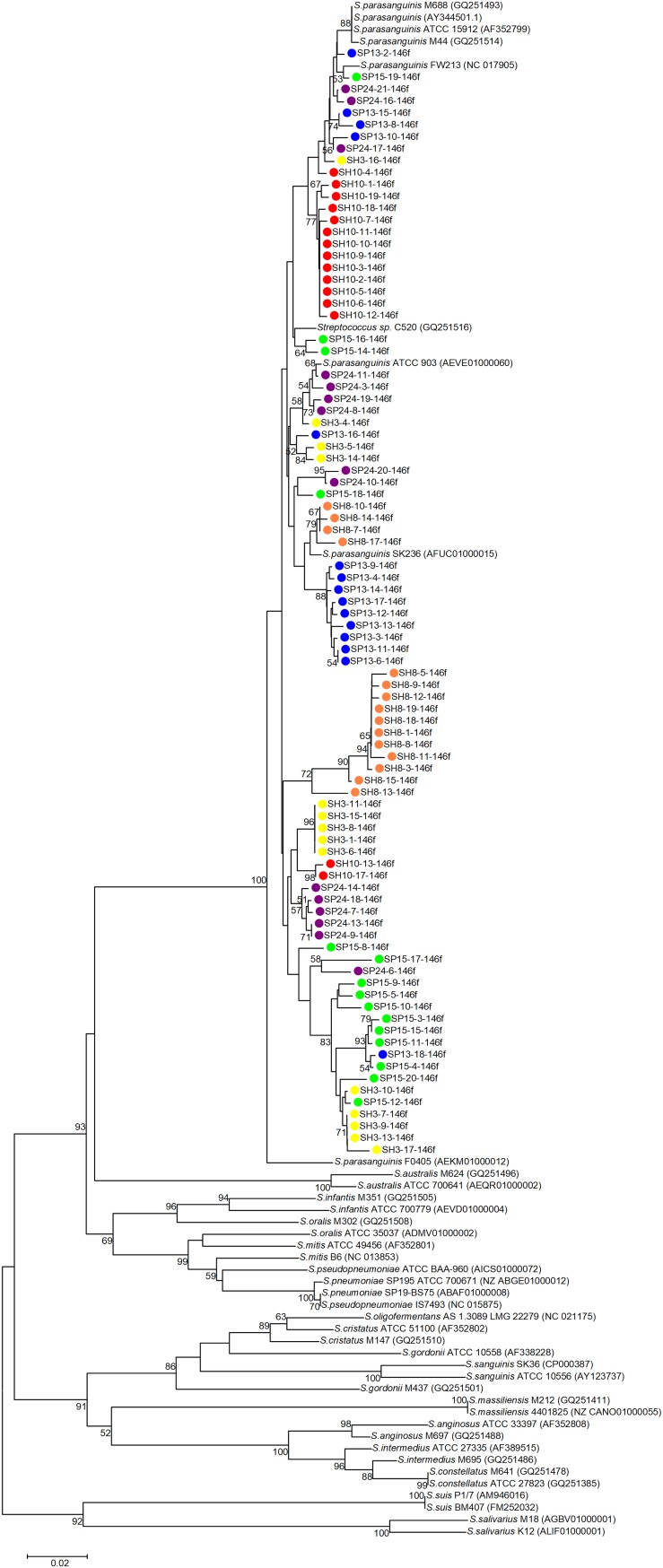

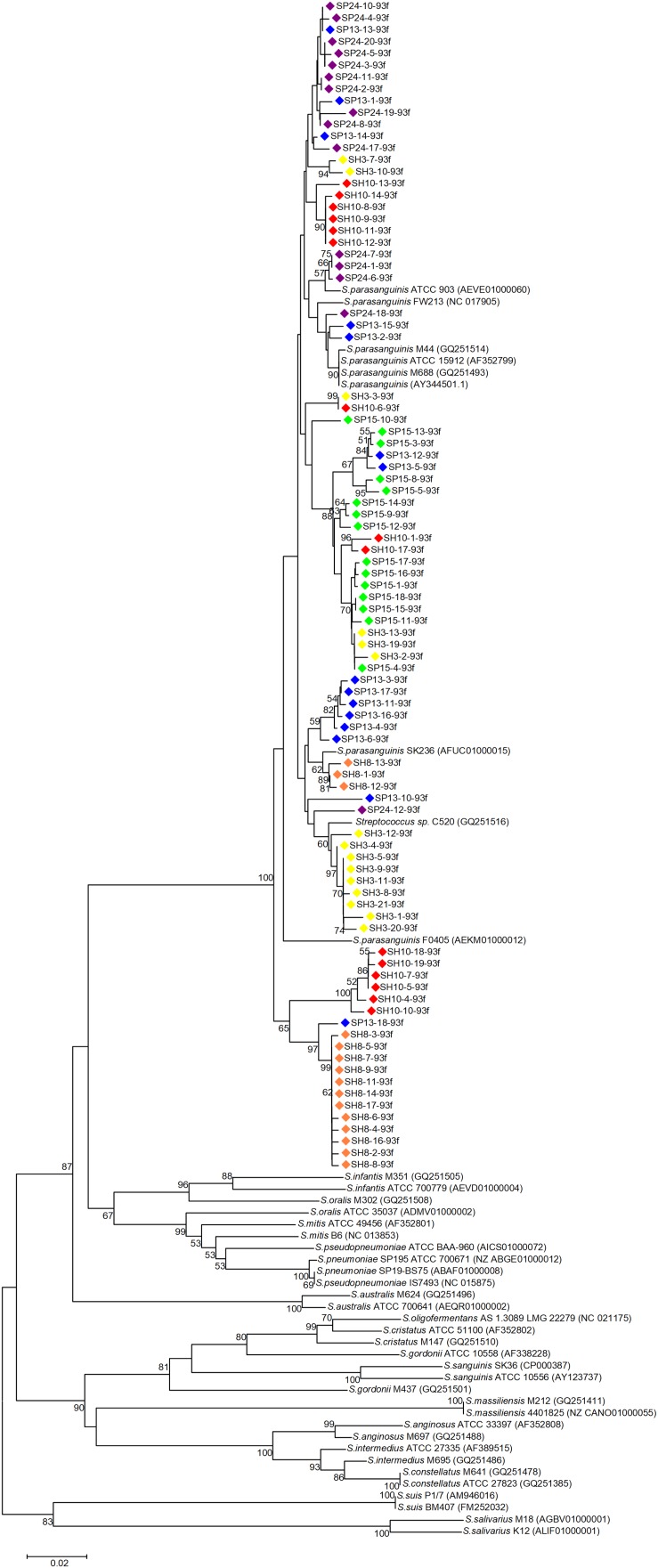

Phylogenetic trees were constructed with the cloned sequences obtained with primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, respectively (Figures 1, 2). Regardless of the primer pair, all cloned sequences clustered with known S. parasanguinis strains, and separated from other Streptococcus spp. In both trees, the S. parasanguinis sequences, including cloned sequences and reference sequences of known S. parasanguinis isolates, formed different lineages, and the cloned sequences from the same human subjects distributed in at least two different lineages (Figures 1, 2, and Supplementary Figure S6).

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the groEL gene fragments cloned by the primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r from the saliva of six human subjects and those of known Streptococcus species. The cloned sequences of the present study are labeled by dots of varied colors, and clones of the identical color are from the saliva sample of one person. Strains of known Streptococcus species retrieved from the GenBank are indicated by italics, and the accession numbers of their groEL genes are given in parentheses following the bacterial names. Bootstrap values greater than 50% are indicated at the nodes.

FIGURE 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the groEL gene fragments cloned by the primer pair Spa93f-Spa525r from the saliva of six human subjects and those of known Streptococcus species. The cloned sequences of the present study are labeled by dots of varied colors, and clones of the identical color are from the saliva sample of one person. Strains of known Streptococcus species retrieved from the GenBank are indicated by italics, and the accession numbers of their groEL genes are given in parentheses following the bacterial names. Bootstrap values greater than 50% are indicated at the nodes.

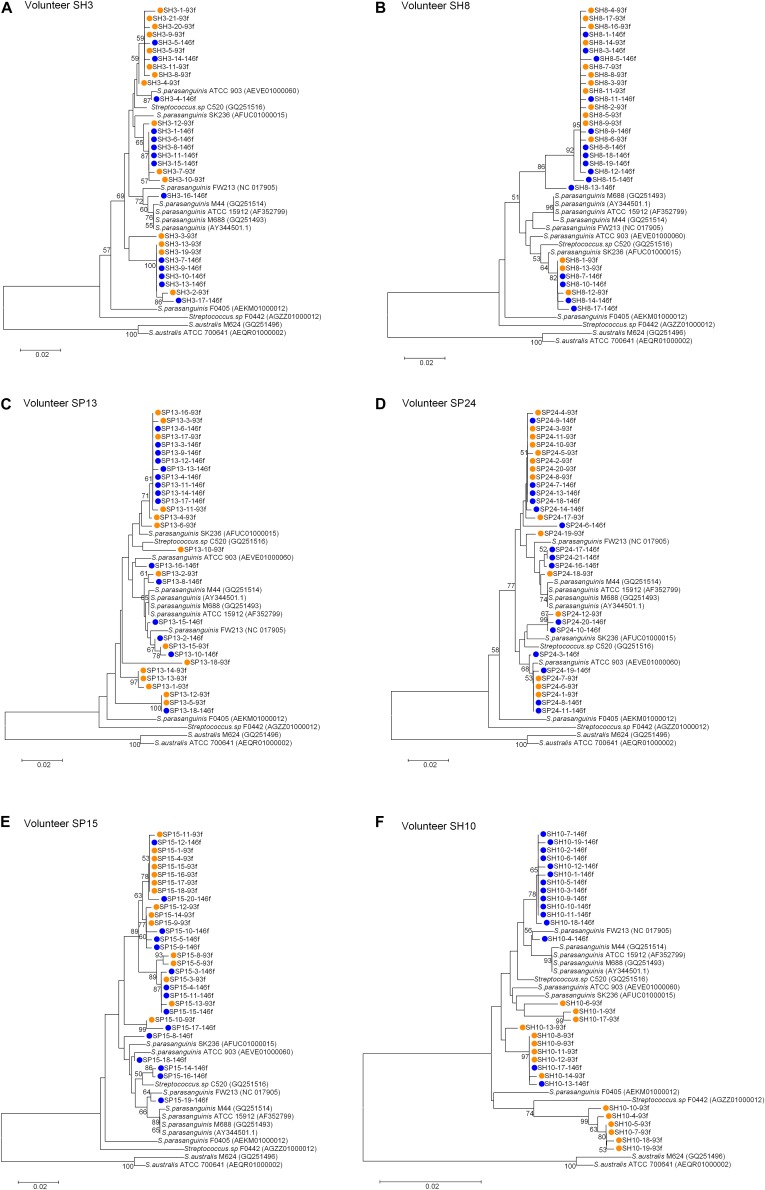

For each of the six people, the sequences cloned with both primer pairs were aligned, and the Spa93f-Spa525r sequences were trimmed so that they are of the same length with Spa146f-Spa525r sequences, and then the processed sequences of both primer pairs were used to build the phylogenetic tree (Figure 3). For four people, the sequences cloned with the two primer pairs distributed among one another in the tree (Figures 3A–D). For one person (SP15), 10 of 15 Spa146f-Spa525r sequences and all Spa93f-Spa525r sequences distributed among one another, and five Spa146f-Spa525r sequences located in clusters distinct from others (Figure 3E). For only one person (SH10), the Spa146f-Spa525r sequences and Spa93f-Spa525r sequences formed separate lineages (Figure 3F). This indicates that in a few but not all humans, primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r may preferentially detect different S. parasanguinis strains.

FIGURE 3.

Phylogenetic trees of the groEL gene fragments cloned by the primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r from the saliva of individual human subjects and those of known Streptococcus species. The sequences cloned with Spa146f-Spa525r are labeled with blue dots, and those cloned with Spa93f-Spa525r are labeled with orange dots. Bootstrap values greater than 50% are indicated at the nodes. (A) The tree of sequences cloned from the saliva of human subject SH3; (B) The tree of sequences cloned from the saliva of human subject SH8; (C) The tree of sequences cloned from the saliva of human subject SP13; (D) The tree of sequences cloned from the saliva of human subject SP24; (E) The tree of sequences cloned from the saliva of human subject SP15; (F) The tree of sequences cloned from the saliva of human subject SH10.

The Standard Curve and Quantification Limit of qPCR Assay of S. parasanguinis

Ten-fold serial dilutions of pGEM-T Easy plasmids containing partial groEL gene sequence of S. parasanguinis were used to generate the standard curve for primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r. In the range of 1 × 102 to 1 × 109 copies per PCR, the standard curves for both primer pairs were highly linear with the R2 > 0.99. The PCR efficiency was 79–96% for the two primer pairs.

To determine the lowest groEL gene copy number that can be detected with the two primer pairs in qPCR assay, fecal samples of three persons, which contained no S. parasanguinis as shown by fecal metagenomic sequencing (Zhang et al., 2015), were spiked with 10-fold serial dilutions of S. parasanguinis cells. The DNA extracted from the spiked feces was used as templates in qPCR with each of the two primer pairs. For both primer pairs, the quantification limit in feces was 5–6 log10 groEL copies/g feces depending on the PCR efficiency. When the PCR efficiency was higher than 90%, the limit was 5 log10 groEL copies/g feces. When the PCR efficiency was between 80 and 90%, the limit became 6 log10 groEL copies/g feces.

Quantification of S. parasanguinis in Human Fecal Samples by Using qPCR With the Primer Pairs Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r

Twenty-two fecal samples that contained varied amounts of S. parasanguinis according to our previous metagenomic sequencing (Zhang et al., 2015) were selected, and S. parasanguinis in these samples were re-quantified as groEL gene copies/ng DNA with qPCR using primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). The melting curves of fecal qPCR products of both primer pairs showed there was no non-specific amplicon and only amplicons corresponding to S. parasanguinis were quantified at the fluorescence reading temperature 82°C (Supplementary Figures S7A,B). Because Spa93f-Spa525r produced an amplicon with the genomic DNA of S. salivarius as templates under convention PCR condition (Supplementary Figure S3), the fecal qPCR products of Spa93f-Spa525r were also run on 1.5% agarose gel to check the specificity, and there was no non-specific amplicon (Supplementary Figure S7C).

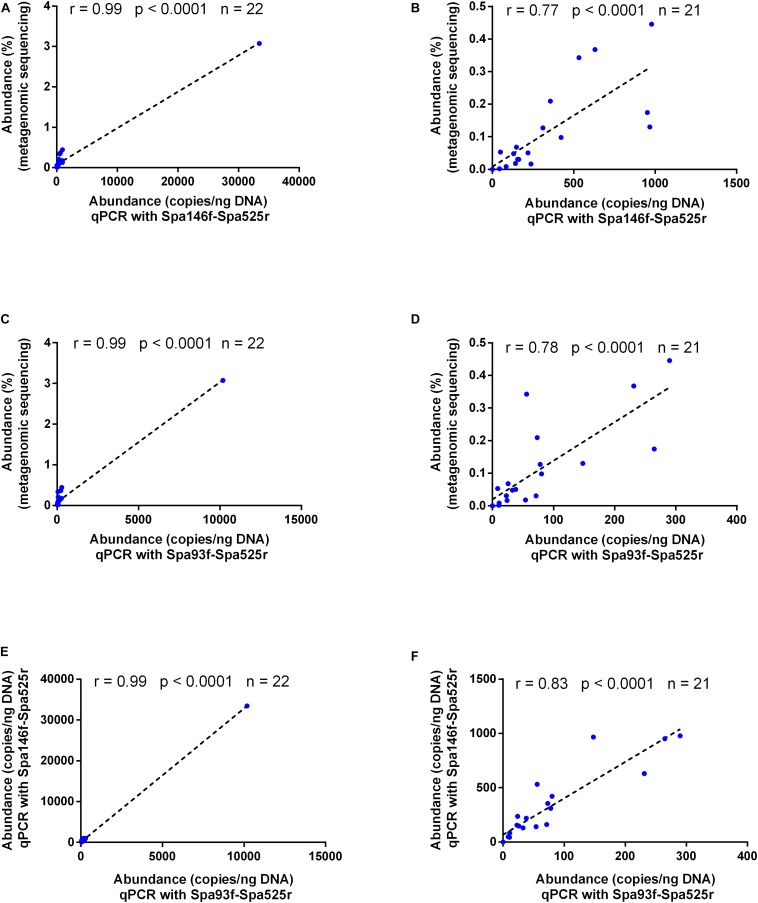

As shown by Pearson’s correlation analyses, the fecal S. parasanguinis abundances measured with either primer pair were well correlated with those obtained with metagenomic sequencing (r = 0.99 and p < 0.0001 for both Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, Figures 4A,C), and data obtained with the two primer pairs also showed strong and significant correlation (r = 0.99 and p < 0.0001, Figure 4E). After the removal of the sample that had extraordinarily higher level of S. parasanguinis than any other samples, the correlations were still strong and significant among the results of metagenomic sequencing, qPCR with Spa146f-Spa525r, and qPCR with Spa93f-Spa525r (r was between 0.77 and 0.83, and p < 0.0001, Figures 4B,D,F).

FIGURE 4.

Bivariate scatterplots showing the Pearson’s correlation of the human fecal S. parasanguinis concentrations determined by metagenomic sequencing, qPCR with primer pair Spa146f-Spa525r, and qPCR with primer pair Spa93f-Spa525r. The correlation coefficient (r), p-value, and the number of fecal samples (n) are shown in each plot. The relative abundances of S. parasanguinis in the metagenomic sequencing dataset were calculated using MetaPhlAn (Segata et al., 2012) in our previous study (Zhang et al., 2015). (A,C,E) The correlation among the data of all 22 tested fecal samples. (B,D,F) The correlation among the data after the removal of one fecal sample containing extraordinarily higher level of S. parasanguinis than other samples.

Quantification of S. parasanguinis in Human Saliva Samples by Using qPCR With the Primer Pairs Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r

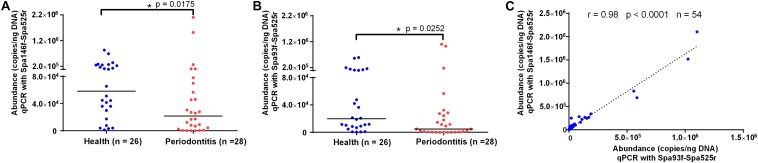

qPCR using Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, respectively, was performed to quantify the abundances of saliva S. parasanguinis in 26 healthy people and 28 periodontitis patients (Supplementary Table S6). The melting curves of saliva qPCR products of both primer pairs showed there was no non-specific amplicon and only amplicons corresponding to S. parasanguinis were quantified at the fluorescence reading temperature 82°C (Supplementary Figures S8A,B). The 1.5% agarose gel of saliva qPCR products of Spa93f-Spa525r showed no non-specific amplicon was generated (Supplementary Figure S8C). No matter which primer pairs were used, the results showed that healthy people had significantly higher level (2.7 fold for Spa146f-Spa525r and 4.2 fold for Spa93f-Spa525r) of saliva S. parasanguinis than periodontitis patients (Figures 5A,B).

FIGURE 5.

The saliva S. parasanguinis concentrations determined by qPCR with two primer pairs in periodontitis patients and periodontally healthy people. (A) The saliva S. parasanguinis abundance quantified with Spa146f-Spa525r in oral health and periodontitis. (B) The saliva S. parasanguinis abundance quantified with Spa93f-Spa525r in oral health and periodontitis. The line among the dots represents the median. The values were compared between two groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. (C) Pearson’s correlation of the human saliva S. parasanguinis concentrations determined by qPCR with two primer pairs, Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r. The correlation coefficient (r), p-value, and the number of fecal samples (n) are shown.

The saliva S. parasanguinis quantity obtained with the two primer pairs showed strong and significant correlation (r = 0.98, p < 0.0001, Figure 5C).

Discussion

In the present study, two pairs of PCR primers that specifically target the groEL gene of S. parasanguinis, Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r, were designed and validated. In many previous studies that developed PCR primers specific for certain bacterial taxa, PCR assays were performed with the genomic DNA of dozens of bacterial strains belonging to targeted and non-targeted taxa as the templates, and the specificity of the primer pairs were validated by the results that only targeted bacteria produced amplicons of expected size (Junick and Blaut, 2012; Leigh et al., 2018). However, this requires rich collection of cultures of bacterial strains of relevant taxa, which not every lab is capable to have. We used an alternative strategy, which made use of large amounts of reference DNA sequences of large-scaled public databases and combined in silico PCR simulation with experimental PCR-clone library and sequencing, to evaluate the specificity of the primer pairs. We first blast the primer sequences against DNA sequences deposited in public databases, including the genomes of 30 S. parasanguinis strains from the NCBI genome database8, the ∼23,000 groEL gene sequences of prokaryotes, eukaryotes, and archaea of the Chaperonin Sequence Database9 (Junick and Blaut, 2012), and 49,976,402 non-redundant DNA sequences of the NCBI nucleotide collection (nr/nt). Then, we perform in silico PCR simulation (Cao et al., 2005) with individual primer pairs and the 866 groEL gene sequences of 64 Streptococcus species downloaded from the Chaperonin Sequence Database as templates, and confirmed the simulating results by doing experimental PCRs in which the genomic DNA of a few human commensal Streptococcus strains was used as the templates. Finally, Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r were respectively used to amplify and clone S. parasanguinis groEL gene from 6 human saliva samples that contain complex streptococci populations, and phylogenetic analyses were performed to check whether the cloned amplicons were affiliated to S. parasanguinis. Our results suggest that the two primer pairs can specifically detect S. parasanguinis.

The quantitative results of qPCR assays that were respectively generated with Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r were highly consistent. In both human feces and saliva, the S. parasanguinis quantity determined with the two primer pairs showed strong and significant correlation. The levels of human fecal S. parasanguinis quantified with each of the two primer pairs correlated well with those determined with metagenomic sequencing of fecal total DNA that is independent of PCR amplification. In addition, qPCR using either primer pair showed periodontitis patients had significantly lower level of saliva S. parasanguinis than healthy people. These results suggest that both Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r can be used to quantify the human fecal and saliva S. parasanguinis. Compared to Spa93f-Spa525r, Spa146f-Spa525r required less stringent condition as predicted by in silico PCR simulation and lower annealing temperature as shown by experimental PCR to achieve specific amplification, therefore, we suggest to use Spa146f-Spa525r in the case that there are non-specific amplicons and PCR specificity needs to be improved by enhancing annealing temperature. The qPCR using the two primer pairs can be used to detect and quantify S. parasanguinis in clinical specimen without bacterial culturing, and this can accelerate the pathogen identification for S. parasanguinis-caused diseases or the determination of the association of S. parasanguinis with diseases.

In this study, the S. parasanguinis groEL gene sequences cloned from human saliva formed different clusters in the phylogenetic tree, and those of known S. parasanguinis isolates scattered in these clusters, suggesting the genotype diversity at sub-species level of S. parasanguinis. For individual human subjects, the cloned S. parasanguinis sequences distributed in varied clusters, indicating that the one person harbored multiple genotypes of S. parasanguinis in oral cavity. This is in accordance with previous observations that individual humans harbored more than one genotypes of S. mutans (Cheon et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011) and S. oralis (Do et al., 2009) in oral cavity and multiple genotypes of S. salivarius in small intestine (van den Bogert et al., 2013b). Considering that Spa146f-Spa525r and Spa93f-Spa525r may preferentially detect different S. parasanguinis strains in some people, we suggest that both primer pairs be used when researchers aim to profile the strain-level diversity of S. parasanguinis in complicated bacterial communities. Using the two primer pairs, the S. parasanguinis groEL gene could be cloned and profiled from samples of patients (e.g., periodontitis, and infective endocarditis) and from multiple body locations (e.g., breast milk, intestine, skin, and oral cavity) of healthy peoples. The phylogenetic analyses on the cloned sequences could be performed to see whether certain clade(s) of S. parasanguinis strains are associated with the diseases or body locations, which help explore the evolution of S. parasanguinis in different ecological environments.

The design of bacterial species-specific PCR primers depends on both the strong power of target genes to discriminate phylogenetically close species and as many as possible reference sequences that are of good quality and cover species from a broad range of phylogeny. A good reference sequence database, which collects, curates, and annotates the relevant sequences from diverse species and records the source organisms, can greatly facilitate the primer design. Researchers investigated several conserved house-keeping genes alternative to 16S rRNA gene to differentiate Streptococcus species, including groEL (Glazunova et al., 2009), rpoB (Glazunova et al., 2009), gyrB (Itoh et al., 2006; Glazunova et al., 2009), rpoA (Hee Kuk et al., 2010), soda (Glazunova et al., 2009), dnaJ (Itoh et al., 2006), zwf and gki (Pattarachai et al., 2005), and these genes, except sodA, showed better discriminating power than the 16S rRNA gene. Glazunova et al. (2009) found that the minimal sequence divergence among different Streptococcus spp. was 0.3, 2.7, 0, 2.5, and 3.4% for the 16S rRNA gene, rpoB, sodA, gyrB, and groEL, respectively, and concluded that groEL gene represented the best tool for the identification phylogenetic analysis of Streptococcus species and subspecies. When we started to design the S. parasanguinis-specific primers in 2016, The cpnDB Database10 (Hill et al., 2004) had already contained ∼22,000 groEL sequences of prokaryotes, eukaryotes, and archaea, and among these sequences, 866 were from 64 Streptococcus species, and 8 were from 7 S. parasanguinis strains. Besides, the cpnDB sequences are manually curated to ensure high quality entries. cpnDB is still being updated, and currently contains over 25,000 groEL sequence records of prokaryotes, eukaryotes, and archaea, and includes over 4,000 records from bacterial type strains sequences (Vancuren and Hill, 2019). The ICB database for bacterial gyrB gene was published in 2001 (Watanabe et al., 2001), but cannot be publicly accessed since 2012. There was no publicly available database for other bacterial house-keeping genes mentioned above in 2016. Considering the high divergency of groEL gene sequences among Streptococcus species, and the cpnDB Database that provides rich groEL reference sequences of high quality, we designed the two primer pairs targeting only groEL gene but not two different genes. groEL gene has been used to design PCR primers specific for other bacterial species (Junick and Blaut, 2012; Hossain et al., 2013; Ahmed et al., 2015; Hung et al., 2019). Very recently in July 2019, Ogier et al. (2019) published a reference rpoB database including 45,000 rpoB sequences retrieved from 47,175 genomes sequences from the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) database. Therefore, in the future, it is necessary to design S. parasanguinis-specific PCR primer pair(s) targeting rpoB gene, and use them together with our groEL gene-targeting primer pairs to identify and quantify S. parasanguinis in human microbiome samples with minimal chances of obtaining false positive and/or false negative results.

We did S. parasanguinis-specific qPCR assays for the saliva samples collected from 28 periodontitis patients and 26 periodontally healthy people of Chinese Han ethnic group, and observed that periodontitis patients had significantly lower level of S. parasanguinis than healthy people in saliva. Belstrom et al. (2016, 2017) performed Illumina sequencing of barcoded 16S rRNA gene, and metagenomic and metatranscriptomic sequencing, respectively, for the saliva samples of 10 periodontitis patients and 10 orally healthy individuals from Denmark. In the 16S rRNA gene sequencing dataset, although S. parasanguinis could not be quantified at the species level due to the high similarity among the 16S rRNA genes of different Streptococcus species, Belstrom et al. (2016) found significantly lower relative abundance of the whole Streptococcus genus in periodontitis patients compared to healthy controls; in the Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic datasets, the authors did not detect the difference in saliva S. parasanguinis proportion between periodontitis and oral health (Belstrom et al., 2017). In contrast, when the saliva microbiota composition was compared between 139 chronic periodontitis patients and 447 healthy people of the Danish Scandinavian population using Human Oral Microbe Identification Microarray, researchers reported significantly higher level of saliva S. parasanguinis in periodontitis subjects (Belstrom et al., 2014). These inconsistent observations of the effect of periodontitis on saliva S. parasanguinis abundance may be explained by the varied human subjects recruited, cohort sizes, and techniques used to quantify the bacteria in different studies. In the subgingival plaque microbiota, some studies reported that S. parasanguinis was less prevalent in healthy people than in refractory periodontitis patients, and thus probably play an etiological role in periodontitis(Colombo et al., 2009; Colombo et al., 2012; Fine et al., 2013; Duan et al., 2016).

In the future, to better understand the role of oral S. parasanguinis in periodontitis, both multi-centered case-control and longitudinal cohort studies should be performed, and S. parasanguinis amounts at different oral locations (the saliva, subgingival plaque, and supragingival plaque) can be quantified with qPCR using our PCR primer pairs, and subsequently correlated with the disease and disease severity. The two types of cohort studies must be well controlled by recruiting periodontitis patients of different ages, genders, geographic locations, and ethnic groups, together with the orally healthy individuals matched with the above factors, and people with diseases other than periodontitis should be excluded. Besides, periodontitis severity must be characterized with multiple clinical parameters, including Gingival margin position (GMP), probing pocket depth (PD), attachment loss (AL), and bleeding on probing (BOP), etc. In the case-control cohorts, the amounts of oral S. parasanguinis can be compared between periodontitis and oral health, and among periodontitis of different severity. In the longitudinal studies, the S. parasanguinis quantity can be monitored at different time points as the periodontitis improves or relapses after medical treatments, and as the originally orally healthy people develop periodontitis. By doing so, the association of oral S. parasanguinis at specific oral locations with periodontitis will be demonstrated with least confounding factors, and whether periodontitis changes the distribution of S. parasanguinis at different oral locations will be clarified. Furthermore, S. parasanguinis strains should be isolated from oral samples of periodontitis patients, and orally inoculated into animal models for periodontitis (David et al., 2010; Oz and Puleo, 2011; Jung et al., 2019) to test their capability to directly influence (alleviate or predispose) periodontitis or affect (inhibit or promote) the pathogenesis of periodontal pathogens, and the quantity of S. parasanguinis in the animals can be monitored with the our qPCR method to confirm their survival or study their ecological interactions with the pathogens.

Conclusion

We developed two pairs of S. parasanguinis-specific PCR primers based on the housekeeping groEL gene sequences, and used the primers to detect and quantify human oral and fecal S. parasanguinis by qPCR. The method described here can be used to monitor the response of S. parasanguinis to dietary intervention, medication, and diseases, etc., and provide insights on the role of human commensal S. parasanguinis in health and disease.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://www.cpndb.ca/ and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Ethics Committee of the School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine, China with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. 2012-016) and the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine, China (Document No. 201262).

Author Contributions

JS and QC designed the study. QC and SL performed the experiments. GW, HC, and LZ provided sample materials. HL coordinated the bioinformatics analysis. CZ, XP, and LW coordinated the laboratory management. JS and QC wrote and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This work was supported by grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570809).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02910/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ahmed R., Rafiquzaman S. M., Hossain M. T., Lee J. M., Kong I. S. (2015). Species-specific detection of Vibrio alginolyticus in shellfish and shrimp by real-time PCR using the groEL gene. Aqua. Int. 24 157–170. 10.1007/s10499-015-9916-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul F. S., Warren G., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410. 10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M. R., Paster B. J., Leys E. J., Moeschberger M. L., Kenyon S. G., Galvin J. L., et al. (2002). Molecular analysis of bacterial species associated with childhood caries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 1001–1009. 10.1128/jcm.40.3.1001-1009.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belstrom D., Constancias F., Liu Y., Yang L., Drautz-Moses D. I., Schuster S. C., et al. (2017). Metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis of saliva reveals disease-associated microbiota in patients with periodontitis and dental caries. NPJ Biofilms Microb. 3:23. 10.1038/s41522-017-0031-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belstrom D., Fiehn N. E., Nielsen C. H., Kirkby N., Twetman S., Klepac-Ceraj V., et al. (2014). Differences in bacterial saliva profile between periodontitis patients and a control cohort. J. Clin. Periodontol. 41 104–112. 10.1111/jcpe.12190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belstrom D., Paster B. J., Fiehn N. E., Bardow A., Holmstrup P. (2016). Salivary bacterial fingerprints of established oral disease revealed by the human oral microbe Identification using next generation sequencing (HOMINGS) technique. J. Oral. Microbiol. 8:30170. 10.3402/jom.v8.30170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Wang L., Xu K., Kou C., Zhang Y., Wei G., et al. (2005). Information theory-based algorithm for in silico prediction of PCR products with whole genomic sequences as templates. BMC Bioinformatics 6:190. 10.1186/1471-2105-6-190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Liu Y., Zhang M., Wang G., Qi Z., Bridgewater L., et al. (2015). A Filifactor alocis-centered co-occurrence group associates with periodontitis across different oral habitats. Sci. Rep. 5:9053. 10.1038/srep09053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon K., Moser S. A., Whiddon J., Osgood R. C., Momeni S., Ruby J. D., et al. (2011). Genetic diversity of plaque mutans streptococci with rep-PCR. J. Dent. Res. 90 331–335. 10.1177/0022034510386375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo A. P., Bennet S., Cotton S. L., Goodson J. M., Kent R., Haffajee A. D., et al. (2012). Impact of periodontal therapy on the subgingival microbiota of severe periodontitis: comparison between good responders and individuals with refractory periodontitis using the human oral microbe identification microarray. J. Periodontol. 83 1279–1287. 10.1902/jop.2012.110566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo A. P., Boches S. K., Cotton S. L., Goodson J. M., Kent R., Haffajee A. D., et al. (2009). Comparisons of subgingival microbial profiles of refractory periodontitis, severe periodontitis, and periodontal health using the human oral microbe identification microarray. J. Periodontol. 80 1421–1432. 10.1902/jop.2009.090185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David P., Asaf W., Lior S., Amal H., Dita G., Weiss E. I., et al. (2010). Mouse model of experimental periodontitis induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis/Fusobacterium nucleatum infection: bone loss and host response. J. Clin. Periodontol. 36 406–410. 10.1111/j.1600-051x.2009.01393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do T., Jolley K. A., Maiden M. C., Gilbert S. C., Clark D., Wade W. G., et al. (2009). Population structure of Streptococcus oralis. Microbiology 155(Pt 8), 2593–2602. 10.1099/mic.0.027284-27280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D., Scoffield J. A., Zhou X., Wu H. (2016). Fine-tuned production of hydrogen peroxide promotes biofilm formation of Streptococcus parasanguinis by a pathogenic cohabitant Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Environ. Microbiol. 18 4023–4036. 10.1111/1462-2920.13425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzidic M., Abrahamsson T., Artacho A., Collado M. C., Mira A., Jenmalm M. C. (2018). Oral microbiota maturation during the first 7 years of life in relation to allergy development. Allergy 73 2000–2011. 10.1111/all.13449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine D. H., Kenneth M., Karen F., Debbie T. B., Javier F., David F., et al. (2013). A consortium of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Streptococcus parasanguinis, and Filifactor alocis is present in sites prior to bone loss in a longitudinal study of localized aggressive periodontitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51 2850–2861. 10.1128/JCM.00729-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzosa E. A., Morgan X. C., Segata N., Waldron L., Reyes J., Earl A. M., et al. (2014). Relating the metatranscriptome and metagenome of the human gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 E2329–E2338. 10.1073/pnas.1319284111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett J. A., Simpson P. J., Taylor J., Benjamin S. V., Tagliaferri C., Cota E., et al. (2012). Structural insight into the role of Streptococcus parasanguinis Fap1 within oral biofilm formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417 421–426. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazunova O. O., Raoult D., Roux V. (2009). Partial sequence comparison of the rpoB, sodA, groEL and gyrB genes within the genus Streptococcus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59(Pt 9), 2317–2322. 10.1099/ijs.0.005488-5480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godon J.-J., Zumstein E., Dabert P., Habouzit F., Moletta R. (1997). Molecular microbial diversity of an anaerobic digestor as determined by small-subunit rDNA sequence analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63 2802–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hee Kuk P., Jang Won Y., Jong Wook S., Jae Yeol K., Wonyong K. (2010). rpoA is a useful gene for identification and classification of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the closely related viridans group streptococci. Fems Microbiol. Lett. 305 58–64. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01913.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero E. R., Slomka V., Bernaerts K., Boon N., Hernandez-Sanabria E., Passoni B. B., et al. (2016). Antimicrobial effects of commensal oral species are regulated by environmental factors. J. Dent. 47 23–33. 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. E., Penny S. L., Crowell K. G., Goh S. H., Hemmingsen S. M. (2004). cpnDB: a chaperonin sequence database. Genome Res. 14 1669–1675. 10.1101/gr.2649204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. T., Kim E.-Y., Kim Y.-R., Kim D.-G., Kong K. (2013). Development of a groEL gene-based species-specific multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay for simultaneous detection of Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 114 448–456. 10.1111/jam.12056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung W. W., Chen Y. H., Tseng S. P., Jao Y. T., Teng L. J., Hung W. C. (2019). Using groEL as the target for identification of Enterococcus faecium clades and 7 clinically relevant Enterococcus species. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 52 255–264. 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y., Kawamura Y., Kasai H., Shah M. M., Nhung P. H., Yamada M., et al. (2006). dnaJ and gyrB gene sequence relationship among species and strains of genus Streptococcus. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 29 368–374. 10.1016/j.syapm.2005.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y. J., Miller D. P., Perpich J. D., Fitzsimonds Z. R., Shen D., Ohshima J., et al. (2019). Porphyromonas gingivalis tyrosine phosphatase php1 promotes community development and pathogenicity. MBio. 10:e2004-19. 10.1128/mBio.02004-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junick J., Blaut M. (2012). Quantification of human fecal Bifidobacterium species by use of quantitative real-time PCR analysis targeting the groEL gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 2613–2622. 10.1128/AEM.07749-7711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok S., Kellogg D., McKinney N., Spasic D., Goda L., Levenson C., et al. (1990). Effects of primer-template mismatches on the polymerase chain reaction: human immunodeficiency virus type 1 model studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 18 999–1005. 10.1093/nar/18.4.999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Villoslada F., Olivares M., Sierra S., Rodriguez J. M., Boza J., Xaus J. (2007). Beneficial effects of probiotic bacteria isolated from breast milk. Br. J. Nutr. 98(Suppl. 1), S96–S100. 10.1017/S0007114507832910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh W. J., Zadoks R. N., Jaglarz A., Costa J. Z., Foster G., Thompson K. D. (2018). Evaluation of PCR primers targeting the groEL gene for the specific detection of Streptococcus agalactiae in the context of aquaculture. J. Appl. Microbiol. 125 666–674. 10.1111/jam.13925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco J., Watkins E. R., Obolski U., Peacock S. J., Morris C., Maiden M. C. J., et al. (2017). Lineage structure of Streptococcus pneumoniae may be driven by immune selection on the groEL heat-shock protein. Sci. Rep. 7:9023. 10.1038/s41598-017-08990-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveen Kumar V., van der Linden M., Menon T., Nitsche-Schmitz D. P. (2014). Viridans and bovis group streptococci that cause infective endocarditis in two regions with contrasting epidemiology. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 304 262–268. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogier J. C., Pages S., Galan M., Barret M., Gaudriault S. (2019). rpoB, a promising marker for analyzing the diversity of bacterial communities by amplicon sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 19:171. 10.1186/s12866-019-1546-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oz H. S., Puleo D. A. (2011). Animal models for periodontal disease. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011:754857. 10.1155/2011/754857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.-N., Kook J.-K. (2013). Development of Streptococcus sanguinis-, Streptococcus parasanguinis-, and Streptococcus gordonii-PCR primers based on the nucleotide sequences of species-specific DNA probes screened by inverted dot blot hybridization. Int. J. Oral Biol. 38 43–49. 10.11620/ijob.2013.38.2.043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pattarachai K., Li L., Murray P. R., Fischer S. H. (2005). Use of housekeeping gene sequencing for species identification of viridans streptococci. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 51 297–301. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M., Umeda M., Ishikawa I., Benno Y. (2000). Comparison of the oral bacterial flora in saliva from a healthy subject and two periodontitis patients by sequence analysis of 16S rDNA libraries. Microbiol. Immunol. 44 643–652. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segata N., Waldron L., Ballarini A., Narasimhan V., Jousson O., Huttenhower C. (2012). Metagenomic microbial community profiling using unique clade-specific marker genes. Nat. Methods 9 811–814. 10.1038/nmeth.2066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songjinda P., Nakayama J., Kuroki Y., Tanaka S., Fukuda S., Kiyohara C., et al. (2005). Molecular monitoring of the developmental bacterial community in the gastrointestinal tract of Japanese infants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69 638–641. 10.1271/bbb.69.638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng L. J., Hsueh P. R., Tsai J. C., Chen P. W., Hsu J. C., Lai H. C., et al. (2002). groESL sequence determination, phylogenetic analysis, and species differentiation for viridans group Streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 3172–3178. 10.1128/jcm.40.9.3172-3178.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bogert B., Boekhorst J., Herrmann R., Smid E. J., Zoetendal E. G., Kleerebezem M. (2013a). Comparative genomics analysis of Streptococcus isolates from the human small intestine reveals their adaptation to a highly dynamic ecosystem. PLoS One 8:e83418. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogert B., Erkus O., Boekhorst J., de Goffau M., Smid E. J., Zoetendal E. G., et al. (2013b). Diversity of human small intestinal Streptococcus and Veillonella populations. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 85 376–388. 10.1111/1574-6941.12127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogert B., Meijerink M., Zoetendal E. G., Wells J. M., Kleerebezem M. (2014). Immunomodulatory properties of Streptococcus and Veillonella isolates from the human small intestine microbiota. PLoS One 9:e114277. 10.1371/journal.pone.0114277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancuren S. J., Hill J. E. (2019). Update on cpnDB: a reference database of chaperonin sequences. Database 2019:baz033. 10.1093/database/baz033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viale A. M., Arakaki A. K., Soncini F. C., Ferreyra R. G. (1994). Evolutionary relationships among eubacterial groups as inferred from GroEL (chaperonin) sequence comparisons. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 44 527–533. 10.1099/00207713-44-3-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Lu H., Feng Z., Cao J., Fang C., Xu X., et al. (2017). Development of human breast milk microbiota-associated mice as a method to identify breast milk bacteria capable of colonizing gut. Front. Microbiol. 8:1242. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K., Nelson J., Harayama S., Kasai H. (2001). ICB database: the gyrB database for identification and classification of bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 344–345. 10.1093/nar/29.1.344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Yin A., Li H., Wang R., Wu G., Shen J., et al. (2015). Dietary modulation of gut microbiota contributes to alleviation of both genetic and simple obesity in children. EBioMedicine 2 968–984. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q., Qin X., Qin M., Ge L. (2011). Genotypic diversity of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in 3-4-year-old children with severe caries or without caries. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 21 422–431. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://www.cpndb.ca/ and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.