Abstract

To prepare an autologous cell-based product in a cell processing facility, the raw material, which is collected from a patient, must first be shipped from a medical institution to the facility. The quality of this raw material varies depending on the patient, and variations due to transport methods also occur. Because the quality must be uniform and manufacturing processes need to be adjusted to account for these variations, determining the effect of shipment conditions on raw materials is very important for estimating cell manufacturability in the process design. In this study, a group of medical institutions located in different areas requested similar cell-based products processed by the same manufacturing method to a company that is licensed under the Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine in Japan. Manufacturing reproducibility was analyzed based on 456 cell batches received from two clinics that were processed used the same manufacturing method. The specific growth rates that were observed in the early growth phase supposed that the proliferative potential of the primary cells in the raw material was influenced by transit time. Simultaneously, the variation of the specific growth rates in the late phase were supposed to be hardly occurred. Thus, this study evaluated shipping conditions of the raw materials for an autologous cell-based product, and a strategy for verifying the influence of transportation on quality in manufacturing was suggested.

Keywords: Manufacturing reproducibility, Autologous cells, Individual difference, Specific growth rate, Transit time, Standard deviation

Highlights

-

•

Analysis of manufacturing reproducibility was conducted for an autologous cell-based product.

-

•

Influence of transit time was compared for raw materials collected in different two areas.

-

•

Overnight shipping resulted in slight increase of the variation but there was not sufficient difference statistically.

-

•

Simultaneously, the influence of transit time was suggested to appear in specific growth rates of the early phase.

1. Introduction

Autologous cell-based products used to treat patients as a part of regenerative medicine or cell therapy are produced by one of two groups in Japan, based on new laws that came into effect in 2014 [1], [2]. One of these groups, which markets authorized products, has been certified for safety and efficacy by a licensed company, according to the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act [3]. In general, a product destined for patients that have received regulatory approval are manufactured in the only factory that is certified as having Good Manufacturing Practice for the cell-based product (GCTP; Good Gene, Cellular, and Tissue-based Products Manufacturing Practice). When a product is prepared in the factory, the raw material, which is collected from a patient, is shipped from a medical institution that may be located anywhere throughout the country. On the other, cell-based products can be prepared for use in medical professionals' practices and clinical studies, as outlined in the Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine (RM Safety Act), and these uses come under the jurisdiction of the Medical Practitioners’ Act and the Medical Care Act. According to the RM Safety Act, medical professionals need to be responsible for the safety of the treatment containing the cell-based product, so the product does not receive regulatory approval at the company level. Instead, each treatment is planned and performed by a specific medical institution, and the location at which the raw materials are collected and transplanted is determined by the medical institution. The cell-based products are prepared at the medical institution or by a licensed manufacturing company. Licensed manufacturing companies are inspected by the Pharmaceuticals Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) to check that they adhere to the relevant requirements.

When an autologous cell-based product is prepared as an authorized product, the quality has to be uniform, and variations in manufacturing need to be fine-tuned for each product [4]. The quality of these raw materials is variable and depends on individual patient differences, while additional variation can occur because of transportation from the location where the raw materials were collected. At present, relatively few products manufactured in this way have received regulatory approval. Therefore, sharing knowledge based on the manufacturing of autologous cell-based products for clinical treatment under the RM Safety Act in Japan is invaluable for quality management.

Several medical institutions in different locations can request a similar, not authorized, cell-based product, which have a single manufacturing method, from a licensed manufacturing company under the RM Safety Act. Each of them is considered to be unique in each according to the regulation, but we think that useful manufacturing information can be obtained by performing a combined quantitative analysis of these individual cases. In this study, variations in manufacturing reproducibility depending on transit time were investigated in a cell-based product manufactured using a single method, based on raw materials containing individual differences that were collected by two medical institutions located in different areas.

2. Methods

2.1. Expansion of activated natural killer (NK) cells

All of the manufacturing was carried out at the cell processing facility (CPF) of the Biotherapy Institute of Japan (BIJ) in Tokyo, Japan [5]. Activated NK cells were expanded using an expansion kit (BINKIT®, BIJ, Japan), as described below [6], [7]. The quality tests used to identify NK cells via surface markers and the safety test used to check for microbial contamination are not described here. Blood mononuclear cells were isolated from 50 mL of peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll–Paque (GE Healthcare, Sweden). For the initial activation, the isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were cultured in BINKIT® initial medium plus 5% heat-inactivated autologous plasma in a BINKIT® initial cocktail in a BINKIT® culture flask. After 3 days of cultivation, the cells were transferred to a culture flask containing BINKIT® subculture medium. Fresh culture medium was added to the flask every 2 or 3 days. Around day 9 (intermediate day), the cells were counted and transferred to a culture bag (NIPRO, Japan) for logarithmic growth. The cells were grown in an incubator (Astec, Japan) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were cultured for approximately 3 weeks, after which a quality check was performed to confirm that more than 1 × 109 cells were obtained; the exact number of cells differed based on inter-patient variability. The cells were then transferred to an infusion bag (Terumo, Japan) filled with Ringer's solution (Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Japan) and shipped to the medical institution.

2.2. NK cell manufacturing for clinical use at clinic A

Clinic A is located in Tokyo, Japan. Peripheral blood collected from patients at this clinic was transported to BIJ at room temperature, and PBMCs isolation began the same day. The standard culture period for PBMCs was 21 days, but in some cases this varied depending on the diagnosis made by the doctor. After the prescribed culture period was complete and the quality check was performed according to the doctor's instructions, the cells were shipped back to the clinic under refrigerated conditions.

2.3. NK cell manufacturing for clinical use at clinic B

Clinic B is located in Fukushima, Japan. Peripheral blood collected from patients at this clinic was shipped overnight to BIJ at room temperature, and PBMCs isolation began the next day (around 24 hours after the blood was collected). The standard culture period for the PBMCs was 19 days, but in some cases this varied depending on the diagnosis made by the doctor. After the prescribed culture period was complete and the quality check was performed according to the doctor's instructions, the cells were shipped back to the clinic under refrigerated conditions.

2.4. Selection criteria for selecting the manufacturing case

For the purpose of this study, the above NK cell manufacturing was chosen as a representative cell-based product manufacturing process. The donors were cancer patients, and none of the donors had a history of anticancer drug treatment or radiation therapy. For several of the donors, more than one sample was submitted for manufacturing.

2.5. Calculation of apparent specific growth rate, μapp

In general, the specific growth rate is equivalent to the growth rate of cultured cells in the exponential growth phase. However, the cells grown for this study did not be counted during the exponential growth phase. Instead, the μapp was calculated based on the cell growth rate during the early or late phases, using the following equation (1).

| (1) |

where N1 and N2 are the total number of living cells on the first cell counting day (t1) and the second cell counting day (t2) of culture, respectively. The cell counting quality checks were performed three times during the culture period (that is, first day, last day, and their intermediate day).

3. Results

3.1. Cell manufacturing at a cell processing facility

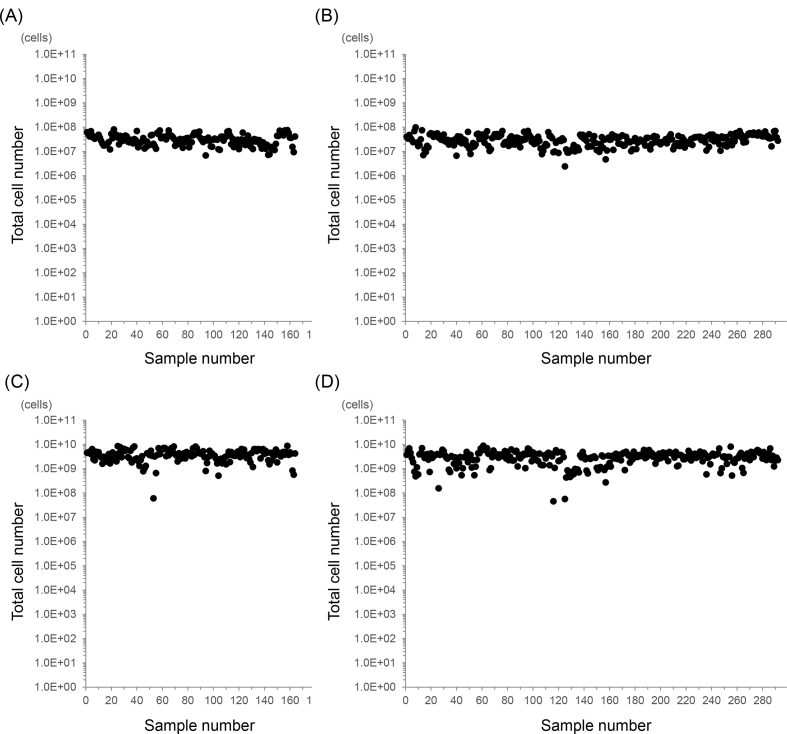

Activated immune cells containing mainly natural killer cells for clinical use were ordered by two clinics based in two different locations and manufactured in the same cell processing facility (CPF). In total, 456 batches of cells (from 151 patients) were processed in the CPF using the same production method over a period of four years from April 2013 to March 2017 (Table 1). Clinic A, which is located 4 km from the CPF, sent 164 samples, and clinic B, which is 203 km from the CPF, sent 292 samples. Cell product manufacturing from the raw material (peripheral blood) began the day the blood was collected in the case of clinic A, and approximately 24 hours after collection in the case of clinic B. The cell counts of the collected and expanded peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are shown in Fig. 1. All of the donors were cancer patients with no history of anticancer drug or radiation treatment. The average cell number, culture period and apparent specific growth rate (μapp) are shown in Table 2. The mean culture period was 21 days for clinic A, but 19 days for clinic B. Seven samples from clinic A (4.3%) and 33 samples from clinic B (11.3%) generated final products with less than the expected cell number (1 × 109). Thus, the average number of cells in the final products manufactured for clinic A was higher than that in the products manufactured for clinic B. However, the average μapp values during the whole culture period were 0.22 and 0.24 for clinic A and clinic B, respectively, indicating that the growth rate was slower in the cells from clinic A. The F-test value for equality of variances between clinic A and B was 1.5, indicating that was not equally distributed (>F0.05).

Table 1.

Number of samples and culture period duration for NK cell manufacturing in a CPF.

| Culture duration (day) | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample from clinic A | 5 | 9 | 10 | 96 | 21 | 12 | 11 | 164 |

| Sample from clinic B | 18 | 242 | 31 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 292 |

Fig. 1.

Total number of PBMCs throughout the manufacturing process. (A) Primary PBMCs collected from patients at clinic A. (B) Primary PBMCs collected from patients at clinic B. (C) PBMCs in final products manufactured from samples from clinic A. (D) PBMCs in final products manufactured from samples from clinic B.

Table 2.

NK cell production manufacturing performance.

| Average total cell number |

Average culture period (day) | Average μapp (day−1) | SD (day−1) | F-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary PBMCs | Final product | |||||

| Sample from clinic A | 3.3 × 107 | 3.9 × 109 | 21.2 | 0.22 | 0.030 | 1.5 (>F0.05) |

| Sample from clinic B | 3.1 × 107 | 3.1 × 109 | 19.1 | 0.24 | 0.036 | |

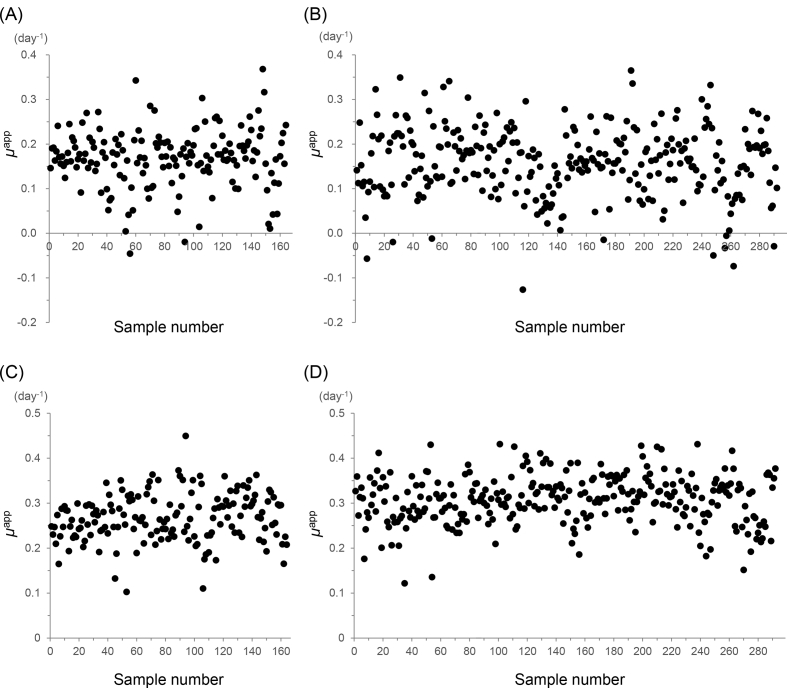

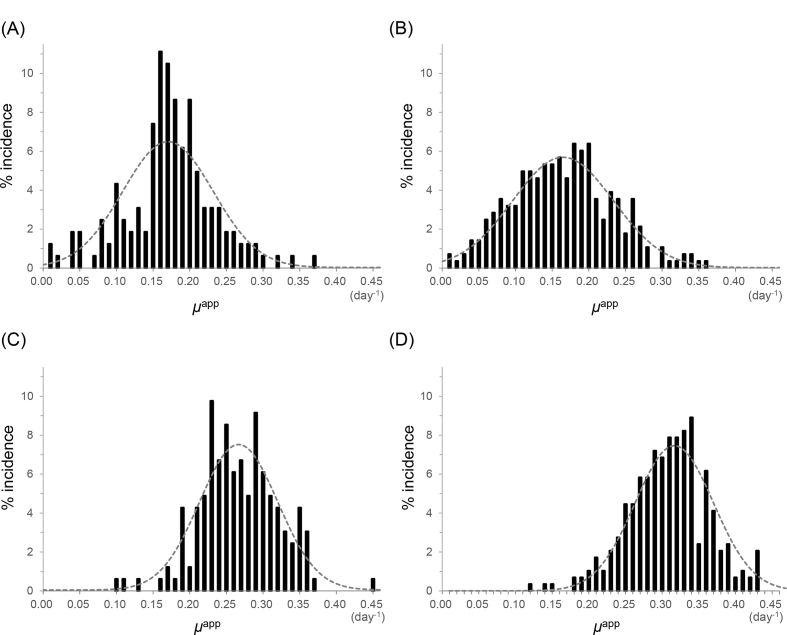

3.2. Variation in μapp in the early and late phases of cell growth

The culturing period was divided into an early phase and a late phase, separated by transfer of the cells to a bag culturing system. The early phase lasted an average of 9 days, at which point the cell growth became stable. The μapp values during the early and late phases (μE and μL, respectively) are plotted in Fig. 2, and the incidence rate is summarized in Fig. 3. Two samples from clinic A (1.2%) and ten samples from clinic B (3.4%) were excluded, as their μE values were <0. Even though the μE was less than 0 for these samples, their overall growth rates were near the average. Additionally, the final cell counts for over half of these samples (1 of 2 and 6 of 10 cases) reached the expected cell number. The results are summarized in Table 3. In the case of clinic A, the average μE was 0.17 with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.062, and the average μL was 0.27 with a SD was 0.053. In the case of clinic B, the average μE was 0.17 with a SD of 0.069, and the average μL was 0.31 with a SD of 0.053. The F-test value for equality of variances between clinic A and B was 1.3 for μE and 1.0 for μL, indicating that each result was equally distributed (<F0.05).

Fig. 2.

Apparent specific growth rate (μapp). (A) The μapp values of cells in the early phase (μE), which lasted from cell isolation to the start of bag culturing, for samples from clinic A. (B) The μE values of samples from clinic B. (C) The μapp values of cells in the late phase (μL), which lasted from the start of bag culturing to the end of the culture period, for samples from clinic A. (D) The μL values for samples from clinic B.

Fig. 3.

Incidence rate of the apparent specific growth rate (μapp). (A) The early phase (from cell isolation to starting the bag culture) for samples from clinic A. (B) The early phase for samples from clinic B. (C) The late phase (from starting the bag culture to the end of the culture period) for samples from clinic A. (D) The late phase for samples from clinic B.

Table 3.

Summary of apparent specific growth rates (μapp) during NK cell manufacturing.

| Number of cases |

μapp in the early phase (μE) |

μapp in the late phase (μL) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deviation by μE<0 | Average (day−1) | SD (day−1) | F-test | Deviation by μL<0 | Average (day−1) | SD (day−1) | F-test | ||

| Sample from clinic A | 164 | 2 | 0.17 | 0.062 | 1.3 (<F0.05) | 0 | 0.27 | 0.053 | 1.0 (<F0.05) |

| Sample from clinic B | 292 | 10 | 0.17 | 0.069 | 0 | 0.31 | 0.053 | ||

4. Discussion

Under the Japanese Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine, medical institutions can request manufacturing of a cell-based product (non authorized preparation) using a single manufacturing method from a licensed manufacturing company. However, the detailed manufacturing conditions can vary depending on the clinic's location or the patient's individual treatment plan. Therefore, reproducibility verification is a very important part of the manufacturing process design and quality control for autologous cell-based products in the treatment plan. In this study, we used the apparent specific growth rate (μapp) as a performance index to quantitatively assess cell quality. This index can be calculated based on conventional cell counting methods, and as such can be applied universally across different cell types and processes [8], [9].

This study was tried to compare the influence due to the difference of manufacturing conditions for products in two clinics, whereas had been confirmed preliminary not to have sufficient differences statistically in the both of final products. Furthermore, there were two main differences between clinic A and clinic B in terms of the manufacturing process: one was the shipping procedure of raw materials and the other was the culture period. Thus, it was difficult to evaluate the difference in manufacturing efficiency between the clinics, as indicated by the μapp values for total manufacturing period shown in Table 2. The influence of shipping conditions on cell growth should be clearly detectable in the early phase of growth, since differences in the proliferative potential of primary cells based on damage to individual cells is evident at the beginning of the culturing period [10]. Therefore, for the purposes of this study, the manufacturing culture period was divided into two phases, before and after the 9th day, based on the quality check point for starting the bag culture process. The reasoning behind this decision is that the inherent specific growth rate of the collected cells becomes stable and cell-specific after day 9, whereas any cell damage that occurred during transport or storage may have a strong impact on the growth rate of the primary culture. As shown in Fig. 2, these growth rate distribution pattern was similar for the samples from both clinics in the early and late phases, although more samples from clinic B exhibited negative growth rates (μE < 0) than those from clinic A in the early phase. It was supposed that the negative growth rates were occurred due to less proliferating living cells in the starting materials by unexpected factors on the collected blood. These samples were excluded from the summary shown in Fig. 3 because as such did not exhibit an adequate μapp value. Olson et al. reported that shipping cells at room temperature results in better viability, cell yield, and function, so we primarily focused on the impact of transit time in this study [11]. While more than one cell product was manufactured from samples from several of the donors, differences between products generated from a single donor are not discussed here, as the sample size was small and variations with health problem could have occurred depending on the collection day.

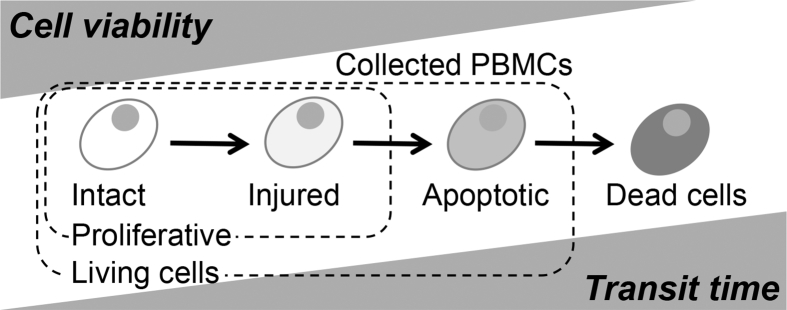

Although the μE values were calculated to estimate the decay of raw materials by transit conditions, the average μE values for clinic A and clinic B were similar and significant difference was not obtained statistically. Then, amid these matters, it was supposed that there was a slight difference of the SDs between the clinics (Table 3). The SD should indicate individual differences and the influence of transit time. The SD for clinic B was higher than that for clinic A, despite the fact that a similar number of samples was collected from patients at both clinics. The proliferative potential of the primary cells from clinic B may have been more influenced by shipping than those from clinic A because of the overnight shipping. The states of influenced cells must exist between the state of viable and dead cells, and therefore, cell populations can be classified into four categories (Fig. 4), where injured or apoptotic cells would not proliferate at the beginning of the culturing period. These primary cells may have temporarily or permanently stopped the proliferating, as indicated by the higher rate of non-growing cell samples (μE < 0) from clinic B compared with clinic A. The elevated SD for samples from clinic B may still be within the tolerance range for the process, because even though the μE values decreased, cell growth continued. A study by Posevitz-Fejfár et al. concluded that overnight shipping of blood samples does not alter the yield and viability of PBMCs isolated from the samples, so these shipment conditions could be suitable for manufacturing expanded PBMCs [12]. However, if the transit time is longer than one day, the condition of cells might begin to deteriorate, making this an inappropriate shipping method for the manufacturing process explored here.

Fig. 4.

Time-dependent cell decay model for transporting peripheral blood samples.

The average μL values were different between the samples from clinic A and clinic B, but they were equally distributed and the SDs were very similar for both clinics (Table 3). The μL values had a relatively standard normal distribution (Fig. 3). Since the μL value reflects the quality of the raw material, we predicted that the SDs for the two clinics would be similar and that the distribution of the μL values would be similar to that of the differences between individual donors. While the standard deviation reflects processing errors, the effect is expected to be relatively small because this culture method does not include any enzymatic passage treatments. The difference in the average μL values may be due to the standard culture period used for the samples from each clinic. The standard culture period was 21 days for samples from clinic A, whereas it was 19 days for samples from clinic B (Table 1). In autologous human cell culture, the growth rate often decreases after a certain period of time [13]. Furthermore, the growth rate can decrease as cell density in the culture bag increases toward the end of the production process [14]. Therefore, when μL values were classified according to the culture period, the results were obtained as shown in Table 4. And then we concluded that the difference in culturing time accounted for the shift in the average μL value. The total number of cells in the final product depends on the culture period, so the average total cell number from samples from clinic A was larger than that of samples from clinic B (Table 2).

Table 4.

Summary of apparent specific growth rates in the late phase (μL) for each culture period.

| Culture duration (day) | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average μL (day−1) | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| Number of samples | 23 | 251 | 41 | 97 | 21 | 12 | 11 |

5. Conclusions

The results from this study suggest that variations in the proliferative potential of autologous mononuclear cells cultured in the same way are due to individual donor differences, and that the reproducibility of this manufacturing method is relatively high. Transit time had a small effect on the proliferative potential of mononuclear cells expanded from peripheral blood samples, and this effect was supposed to be most evident in the early phase of cell growth. While overnight shipping resulted in an increased rate of damaged samples, this effect was relatively small and most of the samples tested still exhibited reasonable growth rates. This shows that a transit time of 1 day at room temperature is acceptable for transporting peripheral blood a raw material in this manufacturing process.

Conflicts of interest

Nothing declared.

Acknowledgments

This research is partially supported by the project of “Development of Cell Production and Processing Systems for Commercialization of Regenerative Medicine” from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

References

- 1.Hara A., Sato D., Sahara Y. New governmental regulatory system for stem cell-based therapies in Japan. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2014;48(6):681–688. doi: 10.1177/2168479014526877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okada K., Koike K., Sawa Y. Consideration of and expectations for the Pharmaceuticals, medical Devices and other therapeutic products Act in Japan. Regen Ther. 2015;1:80–83. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konomi K., Tobita M., Kimura K., Sato D. New Japanese initiatives on stem cell therapies. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16(4):350–352. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratcliffe E., Thomas R.J., Williams D.J. Current understanding and challenges in bioprocessing of stem cell-based therapies for regenerative medicine. Br Med Bull. 2011;100(1):137–155. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizutani M., Samejima H., Terunuma H., Kino-oka M. Experience of contamination during autologous cell manufacturing in cell processing facility under the Japanese Medical Practitioners Act and the Medical Care Act. Regen Ther. 2016;5:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng X., Terunuma H., Nieda M., Xiao W., Nicol A. Synergistic cytotoxicity of ex vivo expanded natural killer cells in combination with monoclonal antibody drugs against cancer cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;14:593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terunuma H., Deng X., Nishino N., Watanabe K. NK cell-based autologous immune enhancement therapy (AIET) for cancer. J Stem Cells Regen Med. 2013;9(1):9–13. doi: 10.46582/jsrm.0901003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heathman T.R.J., Rafiq Q.A., Chan A.K.C., Coopman K., Nienow A.W., Kara B. Characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells from multipledonors and the implications for large scale bioprocess development. Biochem Eng J. 2016;108:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kagihiro M., Fukumori K., Aoki T., Ungkulpasvich U., Mizutani M., Viravaidya-Pasuwat K. Kinetic analysis of cell decay during the filling process: application to lot size determination in manufacturing systems for human induced pluripotent and mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Eng J. 2018;131:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hata N., Jinguji H., Kino-oka M., Taya M. Cell behavior analysis to evaluate proliferative potentials of human lymphocytes expanded and activated for therapeutic use. J Biosci Bioeng. 2008;105(5):566–569. doi: 10.1263/jbb.105.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson W.C., Smolkin M.E., Farris E.M., Fink R.J., Czarkowski A.R., Fink J.H. Shipping blood to a central laboratory in multicenter clinical trials: effect of ambient temperature on specimen temperature, and effects of temperature on mononuclear cell yield, viability and immunologic function. J Transl Med. 2011;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posevitz-Fejfár A., Posevitz V., Gross C.C., Bhatia U., Kurth F., Schütte V. Effects of blood transportation on human peripheral mononuclear cell yield, phenotype and function: implications for immune cell biobanking. PLoS One. 2014;9(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlens S., Gilljam M., Remberger M., Aschan J., Ch ristensson B., Dilber M.S. Ex vivo T lymphocyte expansion for retroviral transduction: influence of serum-free media on variations in cell expansion rates and lymphocyte subset distribution. Exp Hematol. 2000;28(10):1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedfors I.A., Brinchmann J.E. Long-term proliferation and survival of in vitro-activated T cells is dependent on Interleukin-2 receptor signalling but not on the high-affinity L-2R. Scand J Immunol. 2003;58(5):522–532. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]