Abstract

Pediatric patients are at elevated risk of adverse drug reactions, and there is insufficient information on drug safety in children. Complicating risk assessment in children, there are numerous age-dependent changes in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of drugs. A key contributor to age-dependent drug toxicity risk is the ontogeny of drug metabolism enzymes, the changes in both abundance and type throughout development from the fetal period through adulthood. Critically, these changes affect not just the overall clearance of drugs, but exposure to individual metabolites as well. In this study, we introduce time-embedding neural networks in order to model population-level variation in metabolism enzyme expression as a function of age. We use a time-embedding network to model the ontogeny of 23 drug metabolism enzymes. The time-embedding network recapitulates known demographic factors impacting 3A5 expression. The time-embedding network also effectively models the non-linear dynamics of 2D6 expression, enabling better fit to clinical data than prior work. In contrast, a standard neural network fails to model these features of 3A5 and 2D6 expression. Finally, we combine the time-embedding model of ontogeny with additional information to estimate age-dependent changes in reactive metabolite exposure. This simple approach identifies age-dependent changes in exposure to valproic acid and dextromethorphan metabolites and suggests potential mechanisms of valproic acid toxicity. This approach may help researchers evaluate the risk of drug toxicity in pediatric populations.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are the fourth leading cause of death in the United States, are responsible for more than 5% of hospital admissions, and incur an economic burden of 130 billion dollars per year.1,2 ADRs have preventable causes, such as medication errors or drug interactions, however a substantial portion of ADRs have poorly understood, unavoidable etiologies.3 Idiosyncratic ADRs (IADRs) are a class of unavoidable ADRs that are particularly difficult to predict, identify or treat. Idiosyncratic ADRs often arise after an initial period of apparently normal treatment, and they have diverse clinical presentations, ranging from minor skin rashes to organ failure.4 Furthermore, due to their relative infrequency, these reactions often appear only in the late stages of drug development, or after market approval, leading to significant morbidity and mortality. In addition, these events may lead to withdrawal of a drug or the addition of a black box warning, severely curtailing the profitability of drugs, and contributing to the high costs of drug development.5

IADRs are hypothesized to arise due to the formation of reactive metabolites. These by-products of normal drug metabolism can react with protein and DNA, which may lead to organ dysfunction or provoke an immune response.4 These reactive metabolites are often formed by cytochrome-P450-mediated drug metabolism.6–11 Cytochrome P450s (CYPs) are a family of heme-containing proteins which catalyze the oxidative metabolism of over 75% of FDA-approved drugs.12 This process typically yields metabolites that can be readily conjugated to water-soluble carrier molecules for excretion. These conjugation reactions are catalyzed by transferase enzymes including UDP-glucuronosyl transferases (UGTs), sulfotransferases (SULT), glutathione transferases (GSTZ), and others, of which UGTs catalyze the majority of conjugation reactions of FDA-approved drugs.13,14 Transferase-catalyzed and spontaneous reactions with glutathione (GSH) provide a protective pathway to capture and deactivate reactive metabolites, preventing organ damage.15,16

Despite these protective mechanisms, when compared to adults pediatric patients are at even higher risk of ADRs leading to significant morbidity and mortality due to age-specific changes in drug metabolism paired with a lack of clinical drug safety data in children.17,18 Pediatric populations are often neglected during drug development efforts due to the ethical complexities of drug testing, lack of economic incentives, and absence of pediatric centers for clinical studies.19,20 The physiological parameters of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination as well as the expression of specific metabolizing enzymes undergo substantial changes from conception until adulthood.21 These developmental changes, collectively termed ontogeny, lead to changes in both drug clearance and accompanying metabolite profiles – the abundance and types of metabolites generated during metabolism. Metabolite profile differences may increase or decrease exposure to reactive metabolites and may affect the risk of reactive-metabolite-mediated toxicities, such as IADRs.

Clinical trials primarily focus on adults, so that there is an abundance of available data on drug metabolism in adults. We aim to model age-dependent changes in reactive-metabolite-mediated toxicity risk by modeling age-dependent changes in reactive metabolite exposure relative to adult data. Success in this endeavor will require modeling or collecting literature data on three key biochemical phenomena: (1) age-dependent changes in drug metabolizing enzyme expression, (2) metabolites formed by drug metabolism, and (3) metabolite reactivity with proteins and DNA. In this work, we use literature data to construct a model capturing the ontogeny of 23 drug metabolizing enzymes. Modeled enzyme families include oxidative enzymes (cytochrome P450, flavin mono-oxygenase, carboxylesterase), and transferases (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, sulfotransferase, and glutathione transferase).

We constructed a time-embedding network to model the time-dependent dynamics of drug metabolism enzyme expression. The model learns a low-dimensional, time-dependent representation of the data. This representation is analogous to a principal component analysis where the loadings of each component smoothly vary as a function of time. The time-embedding enables the model to learn more complex time dependent dynamics with fewer parameters than would be required for a traditional neural network. To our knowledge, the final model is the most comprehensive model of drug-metabolizing enzyme ontogeny available. Furthermore, in addition to estimating the mean expression, our model is the only ontogeny model to capture population-level variation in enzyme expression as a function of age. In several case studies, we show how this model can be applied to understand clinically observed metabolism ontogeny, and we combine ontogeny predictions with a model of metabolite reactivity to demonstrate how age-dependent reactive metabolite exposure could be assessed.

Data and Methods

Enzyme expression data

Pediatric liver sample data were compiled from 12 studies22–34 involving 241 liver samples from patients ranging in age from eight weeks gestation to 18 years of age and contained expression measurements for 23 enzymes including cytochromes P450 (CYP; enzymes 1A2, 2A6, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, 3A4, 3A5, 3A7), flavin monoxygenase (FMO; enzymes 1 and 3), carboxylesterase (CES; microsomal enzymes 1 and 2, cytosolic enzymes 1 and 2), sulfur transferase (SULT; enzymes 1A1, 2A1, 1E1), glutathione-S transferase (GSTZ1), and UDP-glucuronosyl transferase (UGT; enzymes 2B7, 2B15). The pediatric sample data were compiled from 12 studies. In addition, we included adult measurements of CYP 3A4, 3A5, and 3A7 from the Stevens et al study,28 which also measured pediatric expression of these enzymes using the same methods. Adult data from other studies were not included because we could not guarantee that enzymes were measured using the same methods and under the same conditions as pediatric samples. In addition to enzyme expression levels, pediatric samples were also annotated with gestational age, post-natal age, gender, ethnicity, post-mortem interval (time from death to sample processing), liver/body weight ratio, genotype information and cause of death. Adult samples did not include these metadata. Procedures for measuring enzyme expression can be found in the cited studies. Briefly, enzyme expression was measured by quantitative western blot analysis and normalized to total liver microsomal protein (picomoles per milligram gram microsomal protein or micrograms per milligram microsomal protein). In the case of CYP 3A4 and 3A7, a multiple regression model of dehydroepiandrosterone metabolic activity was used to estimate protein abundance.28

Time-Embedding Networks

The time-embedding network models age-dependent dimensionality reduction. The time-embedding is roughly analogous to principal components analysis, where the eigenvalues associated with each principal component vary smoothly as a function of time. In this case, time corresponds to the age of the patient from whom a sample is taken. The backbone of the model is a delta-encoded time-embedding matrix. Each column corresponds to chronologically ordered and discretely sampled time point. The entries in the matrix are the delta between the current time point and the prior time point, and it is these deltas that are adjusted during learning. A column-wise cumulative sum, running along each row, converts the delta matrix to the time-embedding matrix that is smoothed along the time dimension.

The time embedding matrix is used to compute an embedding vector for each timepoint in the data. For each time point, linear interpolation between the two closest time samples in the matrix yields a single vector. This interpolated vector is fed forward into a neural network, which learns how the time embedding is predictive of downstream target values, such as enzyme levels and variances. This interpolated vector is analogous to the eigenvalues of the principal components at this time point. The weights of the neural network are analogous to the loadings of each data column to the principal components, which are constant across all time points.

The precise time points in the time-embedding matrix are configurable, to enable fine-grained modeling where it is most important. We chose sample timepoints most frequently around the critical period of development immediately after birth but less frequently else-where. The chosen timepoints were −200, −100, 0, 7, and 30 days, followed by 1, 3 and 18 years. Better sampling might improve model accuracy, but we did not perform extensive analyses to determine an optimal choice. To compute the output, the time-sampled vector is combined with optional, time-independent covariates. In this study, covariates considered for modeling included demographic information, genotype data and sample characteristics. Demographic covariates included gender and ethnicity. Sample characteristics included post-mortem interval. Genetic covariates included CYP2E1 genotype (1C* or 1D* alleles), CYP2D6 genotype (*1, *2, *4, *5, *9, *10, *17, and *29 alleles), three GSTZ1 SNPs (32E>K, 42G>R, and 82M>T) and three UGT2B15 SNPs (D85>Y, K523>T, T352>I). The time-embedding and covariate vectors are fed as input to a neural network with two adjacent hidden layers with tanh activation functions. These hidden layers are concatenated and fed into the output layers. The neural network has three fully connected output layers: mean (linear activation), variance (exponential activation) and mixture parameter (sigmoid activation). Together, these outputs fully specify a log-normal-dirac mixture distribution over enzyme log-expression values. The mean and variance are trained to fit log-scaled expression data. The mixture parameter indicates whether protein was detected in the sample, which may occur due to absence of protein, or because the levels are below the detection limit of the measurement device. This mixture distribution is used because expression data is often log-normally distributed when protein levels can be detected,35–37 while some samples in the dataset have zero protein detected. The model was constructed in tensorflow and trained by backpropagation with the SciPy L-BFGS optimizer.38

The model was trained to maximize the log-likelihood of the data with respect to the model’s estimate of the mixture distribution parameters. Formally, given samples i = 1, …, N, expression data xi, binary indicators yi = I(xi > 0), and model estimates of the mean μi, standard deviation σi and mixture parameters ιi, the likelihood of the data is

| (1) |

Taking the logarithm and simplifying by allowing 0 · log 0 = 0, we can see that

| (2) |

which is a sum of a standard machine learning loss function, the cross entropy error,39 and the log-likelihood of the predicted log-normal distributions.

To improve the interpretability of the time-embedding, we ensured that all the weights in the fully connected layer applied to the time-embedding were positive. This was accomplished by imposed a gamma prior on the fully connected layers from the time-embedding to the hidden layer and from the hidden layer to the mean expression output.40 Given a fully-connected layer – a linear transformation with the form y = Wx + b − with weights W, the gamma prior expresses W in terms of another matrix V of equal size by applying an element-wise exponential transform, W = eV. Therefore, the individual components of W are positive, so that a negative sign in the time-embedding deltas will be propagated without change of sign to estimate mean expression.

All the weights of the network were subject to a regularization penalty to prevent overfitting. For most of the weights, we used an L2 penalty

| (3) |

with a coefficient of L = 10. For those weights with the gamma prior, the gamma penalty was used:

| (4) |

where k and θ were chosen to be 0.001 and , respectively. This choice creates a prior expectation that the mean value of each weight is small (kθ ≈ 0.03), while the variance is close to one (kθ2 = 1).

To evaluate the model, we used a combination of three metrics. First, the mixture parameters, ιi, were evaluated by calculating area under the receiver operator curve (AUC), by treating the mixture output as a binary classifier of the indicators, yi. Second, we evaluated the mean expression estimates, μi, compared to the log-scaled expression data, log(xi), by Pearson correlation (R2). We also evaluated mean expression estimates by normalized Pearson correlation (NR2), by first normalizing the log-scaled expression data by the mean and variance of each enzyme. Finally, to evaluate the predicted log-normal expression distributions, we used a new metric, the average absolute Z-score (AAZ). Briefly, if each sample log(xi) were drawn from a known normal distribution with mean, μi, and variance, „ the expected value of the AAZ is

| (5) |

The sample value of this statistic is

| (6) |

When assessing our model predictions, the ideal AAZ is 0.8 if the expression data fit the model’s predicted log-normal distributions. Above or below 0.8 indicates data that is more or less spread out (respectively) than predicted by the model;.

Signed sensitivity analysis

To interpret the time-embedding learned by the model, we employed a variant of sensitivity analysis which we call signed sensitivity analysis. In sensitivity analysis, a single row vector (feature) of the time-embedding matrix is permuted, and the change in model accuracy is measured by the change in the Pearson correlation for each enzyme (R2). Large changes indicate that the enzyme strongly depends on the value of that feature. This process is repeated for each feature and enzyme to yield a matrix of unsigned sensitivity values. We impute a sign on each sensitivity value by computing the Pearson correlation between each feature vector and the enzyme mean expression prediction. If the correlation is negative, the sensitivity value is reported as negative.

Alternative neural network

We compared the time-embedding network to a standard neural network to demonstrate the effectiveness of time-embeddings in parameterizing neural networks of time-series data. In the neural network, the age of a sample was encoded as a vector of two continuous variables: estimated gestational age in days (EGA), post-natal age in days (PNA) and three indicator variables: fetal, EGA known, and adult. The fetal indicator variable was set to 1 for samples collected prenatally, the “EGA known” indicator variable was set to 1 for samples with an estimated gestational age, and the adult indicator variable was set to 1 for all samples from non-pediatric studies. Adult samples were given PNA values of 6570 days (18 years). This age encoding vector was input to a neural network with the same structure as that used for the time-embedding network decoder, substituting for the sampled time-embedding features. As in the time-embedding network, this vector was combined with optional covariates such as genotype, demographics, and sample characteristics.

Metabolite networks

We collected known metabolites and metabolic reactions of tramadol, dextromethorphan and valproic acid from the PharmGKB (www.pharmgkb.org) and DrugBank (www.drugbank.ca). In cases where multiple enzymes were reported to catalyze the same reaction, the relevant literature sources were reviewed to determine the enzyme(s) with favorable reaction kinetics. Only the most kinetically favorable enzyme(s) were included in the final metabolite networks. For example, in the reaction forming 4-ene valproic acid from valproic acid, CYPs 2A6, 2C9 and 2B6 may all exhibit catalytic activity, but in literature reports the formation rates by 2A6 and 2C9 were orders of magnitude higher than that of 2B6 in recombinant experiments.41 In this case, we assigned the reaction only to 2A6 and 2C9, excluding 2B6. The process of assigning reactions to kinetically favorable enzymes resulted in an approximation of the true metabolic network governing in vivo metabolism. This approach may be prone to errors when an enzyme playing a major role in the adult is not expressed in a child, while a minor enzyme is expressed. In these cases, more robust pharmacokinetic modeling using experimentally determined kinetic parameters would be required. To aid in reproducing and evaluating our approach, complete reaction networks indicating our final reaction assignments are given for each drug in the metabolite profile case studies.

Reactivity modeling

For metabolites collected in the valproic acid case study, we predicted reactivity of each metabolite with glutathione (GSH) using XenoSite, a previously developed model.42,43 Briefly, this model computes a numerical description for each atom in a molecule based on the local topology around that atom. This numerical description is then input to a neural network, which outputs four reactivity scores for each atom, each indicating reactivity with a different substrate (Cyanide, GSH, DNA or Protein). We report the reactivity scores for GSH only. Scores range from zero to one and indicate an atom’s probability of forming a covalent bond with the cysteine sulfur in GSH. In addition, the model outputs a molecule-level reactivity score, which indicates the overall probability that a molecule will form a covalent bond with substrate.

Modeling clinical clearance of tramadol

Clearance of tramadol was modeled as a constant, scalar multiple of CYP2D6 concentration. Demographic data were not available, so we computed expression distributions assuming male, caucasian participants. To fit the model, we performed zero-intercept, variance-weighted regression. Specifically, given N samples enumerated i = 1 … N, 2D6 expression estimates μi, estimated variances and clinically measured clearance values ci, we computed the scalar regression parameter in log space,

| (7) |

This regression accounts for the ontogeny model’s age dependent estimates of both mean expression and variance. For a given sample i, the mean and 67% intervals for clearance are, respectively,

| (8) |

Modeling age-dependent metabolite profiles

We roughly estimated age-dependent changes in metabolite profiles relative to adults without collecting detailed kinetic data by constructing simplified kinetic models with three key assumptions. First, kinetics were assumed to be Michaelis-Menten. Second, substrate concentration was assumed to be much lower than Km for each reaction, so that the kinetics of the system were linearly-dependent on Vmax[S]/Km. Finally, the catalytic rate for all reactions was assumed to be the same in an ideal adult patient whose enzyme expression is matches the population average. Under these assumptions, we express the rate of each enzymatic reaction relative to unknown adult values using the model’s estimate of enzyme expression,

| (9) |

For a given metabolic network, these equations form a system of linear differential equations. We solve for steady state in the adult case, and in the child case, then compute the relative abundance of each metabolite as [S]child/[S]adult. This simplified kinetic model is not suggested as an effective alternative to existing physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) approaches. Instead, we use this model to demonstrate that accounting for ontogeny-related changes in metabolizing enzyme expression may help explain clinically observed effects on drug clearance, metabolite exposure, and drug toxicity.

Data display

Except where indicated, plots of change with respect to age are shown on a semi-log scale to give roughly equal display width to each of four critical periods of development: fetal, neonatal (less than one month of age), infancy (between one month and one year of age) and childhood (greater than 1 year of age). To achieve this weighting, ages over 1 day after birth are plotted on a log-scale (ln(age) + 1/100), whiles age less than one day after birth are plotted linearly at 1/100th scale (age/100). Fetal samples ages were negative and were calculated as number of days until 41 weeks gestation ((gestational age − 280)/100). We chose 41 weeks to ensure that no fetal samples were assigned the same age as a post-natal sample.

Results and Discussion

In the following sections, we detail the construction and evaluation of an ontogeny model using a pediatric and adult liver enzyme expression dataset (Data and Methods). Our study had four key components: (1) data evaluation, (2) model design and validation, (3) comparison to existing ontogeny models, and (4) case studies of age-dependent metabolite exposure. Throughout the text, we compare results obtained by the time-embedding network to alternative neural networks without a time-embedding.

Literature ontogeny data evaluation

The literature data collected for this project sampled critical periods of development, included samples from several major demographic groups, and showed six distinct age-dependent patterns of expression. To assess the data, we looked at three factors: Sample distribution with respect to demographics, correlations between enzyme groups over time, and correlation between expression and activity. Samples were clustered around the critical period of maturation following birth up through the first year. Samples decrease in frequency with age, but are approximately uniformly distributed from the fetal period through early childhood (Figure 2A). Samples were included from three key United States demographic groups, including Caucasian Americans, African Americans, and Hispanic Americans. Notably, few samples from Asian Americans or Native Americans were collected in the source studies. Therefore, key drug metabolizing enzyme variations common in these populations, such as variations in CYP2D6 common among Asians, cannot be assessed in this study.44 Pairwise correlations among enzymes in these data show patterns of expression which have been previously reported in the literature, both in the data collected for this project, and in other literature (Figure 2B).45–48 In particular, two strong correlation clusters are evident, one corresponding to enzymes predominantly expressed in fetal samples (CYP3A7, FMO1 and SULT1E1), and the other corresponding to enzymes which are abundant in adults but less abundant in fetal samples. The adult expression enzymes included most of the CYP enzymes, as well as SULT2A1, GST, and UGT enzymes. Three smaller clusters are also present, one consisting of CYPs 2A6 and 2B6, one containing three of the four carboxylesterases, and one containing enzymes CYP3A5 and SULT1A1. This last group exhibits essentially no change as a function of age and thus clusters separately (Figure S3). Finally, for the six enzymes with catalytic activity measured by rate of metabolism of marker substrates, there were significant correlations between activity and expression measurements (p < 0.05, Figure S2). In this work, we do not model activity. However, these correlations suggest that activity can be estimated from expression for some enzymes.

Figure 2: Enzyme expression data on 23 enzymes collected by Hines et al reflect known age-dependent patterns of metabolizing enzyme expression.

(A) Liver specimens in the dataset included samples from patients with a diverse background of ages, ethnicities and genders. In particular, samples are densely distributed in the critical period of development from birth to one month of age. (B) A correlation plot of enzyme expression among the 23 enzymes shows two main clusters, one corresponding to fetal pattern enzyme expression and one corresponding to adult pattern expression.

The time-embedding network captures observed expression patterns

We constructed a time-embedding network (Data and Methods) and generated enzyme distribution predictions for each sample in the dataset by leave-one-out cross validation. In the following section, we use these data to evaluate the model in four ways: overall accuracy, accuracy for individual enzymes, interpretation of learned features, and comparison to alternative architectures.

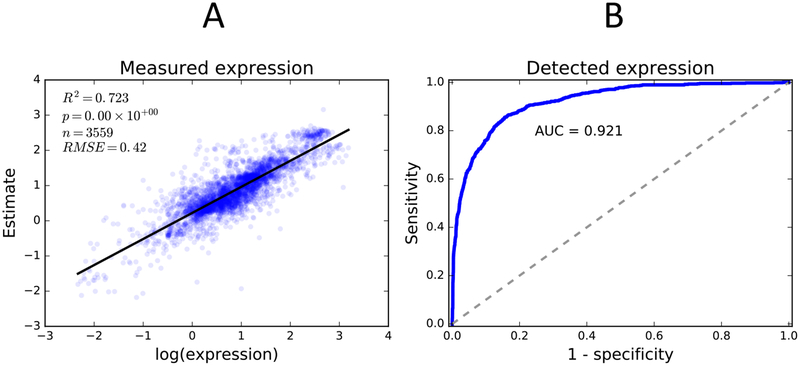

The time-embedding network was able to produce accurate population-level enzyme expression distributions (Figure 3). The time-embedding network predicted enzyme expression with high correlation (R2 = 0.72, log-scaled expression correlation). We also computed correlation after normalizing each enzyme to account for differences in baseline expression, which may lead to erroneously high correlations via Simpson’s paradox. Even when normalized, the time-embedding network still achieves a good correlation (R2 = 0.35). To evaluate the quality of the model’s predictions of variance, we calculated the absolute average Z-score (AAZ, methods). The distributions predicted by the model yield an AAZ close to the expected value for a normal distribution (AAZ=0.86). Finally we evaluated the model’s predictions of expression detection rate (a binary variable) by computing area under the receiver operator curve (AUC), which in our case yielded a very high score (AUC=0.92). In total, these statistics suggest that, while the model cannot accurately predict expression for individual samples, the predicted distributions approximate the data as a whole.

Figure 3: The time-embedding network accurately estimates enzyme abundance and predicts enzyme detection.

(A) Scatter plot of model predicted expression versus measured sample expression for all enzymes exhibits a strong correlation (R2 = 0.72). (B) Receiver operator curve of model predicted detection versus detected protein in liver samples for all enzymes exhibits strong predictive capacity (AUC = 0.92).

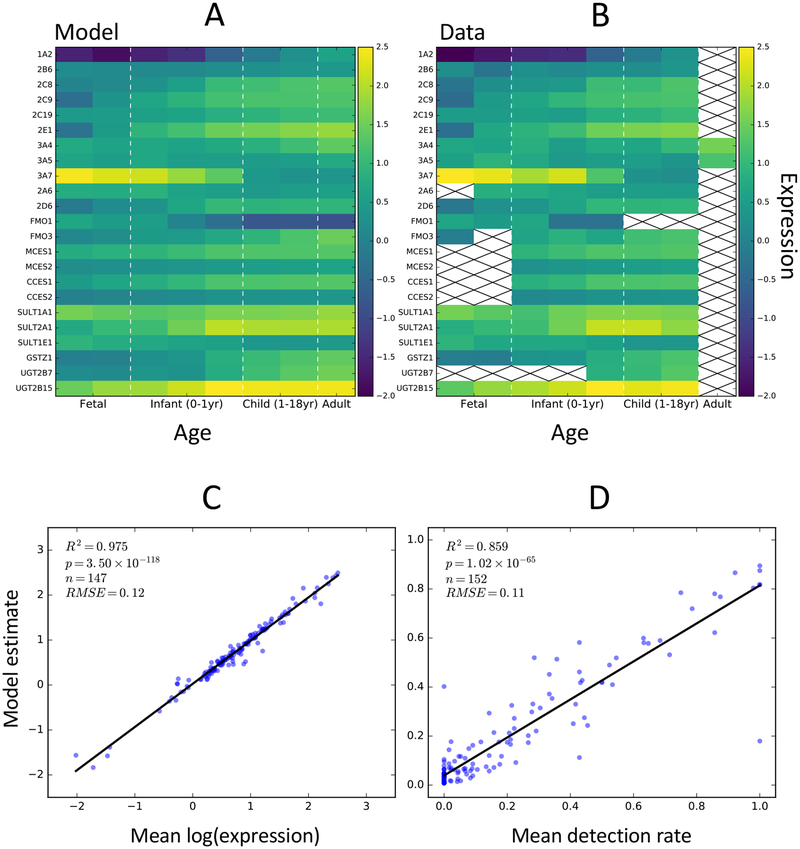

The time-embedding network was able to accurately estimate age-dependent changes in population-level enzyme expression distributions for each modeled enzyme (Figures 4, S1, S3, Table S1). To easily compare the data to predicted model distributions, we binned the data and cross-validated predictions into the same eight age bins used in the construction of the time-embedding matrix (Figure 4A,B, S4). Mean expression and mean detection rate predictions for each bin were strongly correlated with the data (R2 values 0.98 and 0.86, respectively; Figure 4C,D). In addition, we calculated the same statistics used in the global evaluation (RMSE, R2, AAZ, AUC) for each individual enzyme (Table S1). The model predicted well-calibrated normal distributions for each enzyme, with AAZ scores varying between 0.77 and 0.95. Individual enzyme correlations varied substantially (R2 between 0.00 and 0.75, Figure S1). However, enzymes with correlations were directly proportional to the magnitude of change in expression with age (Figure S3, S5). Enzymes with little age-related change in expression had low correlations, but were still well approximated by the predicted expression distributions. This observation is consistent with our hypothesis that the model is able to estimate population-level variation, but not necessarily able to predict the specific expression levels for each sample from the available information.

Figure 4: time-embedding networks accurately estimate age-dependent population-level expression patterns for 23 drug metabolism enzymes.

(A) Mean model estimates of enzyme log expression over 8 distinct age groups. Model estimates from leave-one-out cross-validated experiments were used. (B) Mean log expression for each enzyme and age group calculated from the training data. Crosses indicate bins without sufficient data to estimate population means. (C) Model estimates of log expression for each enzyme and age group are strongly correlated with the training data (R2 = 0.98). (D) Model estimates of detection rates for each enzyme and age group are strongly correlated with the training data (R2 = 0.86)

The time-embedding matrix can be viewed as a set of three row vectors or features. These features can be interpreted in terms of known ontogeny patterns. The features learned by the time-embedding network include one primarily decreasing feature (0), one increasing feature (2), and one feature exhibiting a low-magnitude, bidirectional variation with time (Figure 6A). We performed a signed sensitivity analysis to detect which time-embedding features were used to generated the distribution output for each enzyme (methods, Figure 6B). Fetal pattern enzymes CYP3A7, FMO1 and SULT1E1 exhibit positive sensitivity to feature 0, suggesting that this feature captures the effect of fetal regulatory mechanisms. Adult pattern enzymes such as CYP1A2, 2C8, 3A4, FMO3, the CES family, the UGT family and the GST family all exhibit strong positive sensitivity to feature 2, suggesting that this feature captures adult regulatory mechanisms. Interestingly, unlike other adult pattern enzymes, CYP 3A4 also exhibits strong negative sensitivity to feature 0. CYP3A4 expression increases much later in development than other adult pattern enzymes, and the combination of features 0 and 2 may describe this alternative regulatory pattern. Finally, many enzymes are weakly sensitive to feature 1, which likely plays a role as a correction factor.

Figure 6: The time-embedding network capture interpretable, biologically relevant patterns of drug metabolism enzyme expression.

(A) The learned time-embedding feature vectors for our model are a type of time-dependent dimensionality reduction which may capture information about regulation of enzyme expression. The data is well described with as few as three time-embedding features. (B) Signed sensitivity analysis reveals specific dependencies between enzymes and time-embedding features.

The time-embedding architecture selected for our model was the best among several alternative architectures with small variations in components (Table 1). In addition, the selected model slightly outperformed linear time-embedding networks, and neural networks. Importantly, the time-embedding matrix allows the model to capture complex time-dependent variation while using relatively few parameters. As the complexity of a function increases, a traditional neural network provided a single dimensional input for time may require many hidden nodes, and thus many parameters, to accurately estimate that function.49 In our experiments, the best time-embedding network required fewer parameters while achieving better performance that the best neural network (860 vs 929 parameters). Among the considered covariates, including demographic data improved model performance, but genotype data were deleterious to model performance. This loss of performance is likely due to increased model complexity combined with a relative paucity of available ontogeny data. It is difficult to identify appropriate covariate effects in complex genotypes considering a large number of alleles without having many thousands of samples for analysis. Additionally, previous studies of GSTZ1 suggest that, except for null variants, genetic variation accounts for substantially less variance in metabolism enzyme activity than ontogeny.33 This weak signal may contribute to the difficulty of our model in identifying the effects of these genetic covariates.

Table 1: The time-embedding network described in this study performs comparably to alternative models with differing hyperparameters, and slightly outperforms standard neural networks.

B is the time-embedding network selected for study in this manuscript. Models 0–6 are variants of the time-embedding network. Models L1–3 are variants with a time-embedding vector but using a linear output instead of a neural network (ie without any hidden layers). Models A1–3 are neural networks without a time-embedding vector and using an alternative encoding of age. An asterisk (*) marks the alternative neural network used in other comparison experiments. A dash (−) indicates no change. TE: number of time embedding feature vectors, H: number of hidden nodes, D: demographic covariates, C: sample collection covariates, G: genetic polymorphism covariates, L: L2-regularization coefficient, γ: gamma prior

| Model components | Cross-validated scores | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | TE | H | D | C | G | L | γ | RMSE | R2 | NR2 | AvgZ | AUC |

| B | 3 | 5 + 5 | yes | no | no | 10 | yes | 0.42 | 0.72 | 0.35 | 0.85 | 0.92 |

| 0 | 2 | +0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | - | - | ||||||

| 1 | 10 | +0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | +0.01 | - | ||||||

| 2 | no | - | - | −0.01 | −0.03 | - | ||||||

| 3 | yes | +0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | +0.04 | - | ||||||

| 4 | yes | +0.02 | −0.03 | −0.05 | +0.16 | - | ||||||

| 5 | 1 | +0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | +0.05 | +0.01 | ||||||

| 6 | no | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||

| L1 | 12 | 0 | no | - | −0.01 | −0.01 | +0.05 | - | ||||

| L2 | 8 | 0 | no | +0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | +0.03 | - | ||||

| L3 | 4 | 0 | no | +0.04 | −0.05 | −0.10 | −0.02 | −0.01 | ||||

| A1 | no | +0.02 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | - | ||||||

| A2 | no | no | - | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.02 | +0.01 | |||||

| A3* | no | 10 | no | - | - | −0.01 | −0.03 | +0.01 | ||||

The time-embedding network can also be used to identify patterns of expression in demographic subgroups (Figure 7). Using the time-embedding network trained on the complete dataset, we performed substitution experiments. In these experiments, we generated virtual samples by modifying the original training data, whereby we set the input demographic values for each sample to a given fixed value. We then computed the expression distributions for each enzyme over all virtual samples using the trained model. In this experiment, we compared average expression of CYP3A enzymes in Caucasian Americans to that of African Americans. Caucasian Americans more frequently express CYP3A5 alleles with truncation or frameshift mutations, which leads to decreased or absent CYP3A5.50 The time-embedding network correctly identified this demographic effect (Figure 7). Interestingly, the best alternative neural network was not able to detect any difference in any CYP3A enzyme between these demographic groups.

Figure 7: The time-embedding network captures known demographic variation in CYP 3A5 expression.

African Americans express CYP 3A5 more frequently and at much higher levels than Caucasian patients. The time-embedding network is able to identify this trend in the data, predicting substantial and statistically significant increases in CYP 3A5 expression in African Americans compared to Caucasians in simulated input data. In contrast, the neural network ontogeny model was unable to detect any demographic difference in CYP 3A expression.

The time-embedding network improves on existing ontogeny models

Our ontogeny model represents a substantial improvement in scope and utility compared to existing literature efforts. No current efforts in this area have attempted to capture population level variation in P450 enzymes. Instead, most studies have focused on fitting simple models, such as hyperbolic or sigmoidal curves, to estimate mean expression of enzymes as a function of age.51,52 In contrast, modeling population distributions may enable us to describe deviations from the “average” individual, which is critical knowledge that could be used to improve clinical trial design by better estimating toxicity risks. To our knowledge, no modeling efforts have used a data set encompassing either the number or diversity of enzymes included in this study, or the number of liver samples. In terms of scope, the largest ontogeny modeling effort we were able to identify in the literature was a study by Johnson et al,51 which modeled eight CYP enzymes by fitting Hill functions to normalized expression data from approximately 10 liver samples per enzyme. Given its similarity in scope, we compared the predictive capacity of this model to what our time-embedding network can achieve for the expression of drug metabolizing enzymes as a function of age.

Models from the Johnson et al study agreed with data from our study, but also exhibited significant limitations. First and foremost, the models from Johnson et al do not predict absolute expression measurements, but are scaled to predict the fraction of adult expression. In each case, adult expression levels were quantified from one sample. While the models estimate mean fraction of adult expression as a function of age, variance is not directly modeled. Instead, they assume that the variance is constant, and estimate it from adult total liver enzyme data, assuming equal variability among all enzymes. In contrast, we estimate variance directly from the sample data, predicting variance as a function of age and predicting variance of each enzyme independently. Further, their modeling approach can only predict monotonically increasing expression with age, and cannot be applied to enzymes which decrease with age or to enzymes with more complex expression patterns. To compare their models directly to our data and the time-embedding network, we normalized our data to fraction of adult expression by computing the average expression in samples aged over 14 years (20 samples), and normalized our cross-validated model output to that of the average predicted adult expression (Figure 8). The time-embedding network fit the data marginally, but significantly better than the Johnson et al models (average RMSE 0.57 vs. 0.59, p = 0.047, one-tail, paired t-test). Notably, the Johnson et al model exhibited substantially higher error on the CYP2C8 data, suggesting the point chosen for normalization in that study was substantially higher than the population mean (Figure 8). Overall, the time-embedding network improves over existing literature models in three key ways: (1) by increasing the scope of modeling to 23 enzymes, (2) by model population-level distributions as a function of age, and (3) by capturing fetal-pattern enzyme expression as well as more complex, non-monotonic expression patterns.

Figure 8: An existing literature model agrees with data from Hines et al, but does not capture population variation and age-related dynamics observed in pediatric liver samples.

The time-embedding network achieved slightly lower average RMSE over all enzymes (0.59 vs 0.57, p = 0.047, one-tailed, paired t-test). In addition, the time-embedding network captured patterns in age-dependent expression which cannot be captured by simple curve fitting models. For example, CYP2D6 displays a slight decrease in expression after one year of age compared to infant and adult expression. The age axis is shown on a log-scale.

Case studies

In this section, we first apply the time-embedding network to two case study drugs, tramadol and dextromethorphan, with known age-dependent changes in metabolism. In the final study, we combine ontogeny modeling with an existing model of small-molecule reactivity to identify possible age-dependent changes in reactive metabolite exposure in valproic acid.

Ontogeny of tramadol clearance by CYP2D6

The time-embedding network captures complex age-dependent expression dynamics not captured with either simple curve fitting models or neural networks. Some of the enzymes modeled by Johnson et al exhibited interesting patterns of expression as a function of age. However, those changes could not be captured by the simple Hill-type equations used in that study (Figure 8). In the case of CYP2D6, both the time-embedding network and the expression data show decreased expression during childhood, relative to infants and adults, but this pattern is not captured by the Johnson et al model. The neural network captures some of the additional variation, but predicts only constant expression level after one year of age and does not capture the dip in expression at intermediate ages (Figure S6).

The pattern of CYP2D6 expression seen in the data and captured by the time-embedding network may partially explain age-dependent clearance of tramadol observed in the clinic. The primary metabolites of tramadol are formed by CYP2D6-mediated O-demethylation and CYP3A4-mediated N-demethylation.53 The O-demethyl and N-demethyl metabolites are observed in similar concentrations in adults, but tramadol metabolism is primarily driven by CYP2D6 mediated O-demethylation in children, due to the delayed maturation of CYP3A4.54–56 Clearance by O-demethylation is particularly important, because the O-demethyl metabolite is also pharmacologically active.57 We scraped clearance data from a literature study of clinical tramadol clearance by Allagaert et al58 using the WebPlotDigitizer software,59 and provide their clearance data and model (Supplementary Data). The data included samples ranging in age from 20 weeks post conception to 60 years of age. Notably, this clinical data appears to exhibit the same pattern of depressed tramadol clearance during childhood that was observed in the CYP2D6 expression data, which is not captured by the pharmacokinetic model produced in that study (Figure 9). Using the time-embedding network, we modeled tramadol clearance as a scalar multiple of CYP2D6 expression and fit the model by zero-intercept, variance-scaled regression (Data and Methods). The resulting clearance model achieves a good fit to the data compared to the pharmacokinetic model from the paper (R2 = 0.41 vs. 0.18). The time-embedding network explains the observed pattern of depressed clearance in childhood relative to infants and adults, and accounts for the variance in the data, with the majority of samples falling within one standard deviation (Figure 9A). In addition, we performed the same modeling procedure using the alternative neural network ontogeny model to predict CYP2D6 expression (Figure 9B). The neural network achieved a substantially poorer fit to the data (R2 = 0.33), did not capture the decrease in tramadol clearance in childhood, and did not explain the variance as accurately as the time-embedding network (likelihood ratio 18.3, p = 0.016, likelihood-ratio test).

Figure 9: The time-embedding network of CYP2D6 maturation predicts tramadol clearance in clinical data better than standard pharmacokinetic models or an alternative neural network ontogeny model.

(A) A one-parameter pharmacokinetic model based on time-embedding estimates of CYP2D6 expression is well-correlated with tramadol clearance data (R2 = 0.41), and is substantially better than a pharmacokinetic model from the same study (R2 = 0.18).58 (B) In contrast, the neural network ontogeny model failed to capture age-dependent dynamics during childhood when compared to the time-embedding network (R2 = 0.33), and it explained less of the variance than the time-embedding network, as measured by likelihood (likelihood ratio 18.3, p = 0.016, likelihood-ratio test). Dashed lines show one standard deviation of model-predicted distributions.

Age-dependent metabolism of dextromethorphan

In addition to single enzyme predictions, the time-embedding network also correctly predicts age-dependent changes in the balance between two metabolic pathways of dextromethorphan (DXM). DXM is metabolized by both CYP2D6 and 3A4 to form O-demethylated and N-demethylated products, named dextrorphan (DX) and 3-methoxymorphinan (3MM), respectively (Figure 10).60 Each product subsequently undergoes the opposite demethylation reaction to form the product 3-hydroxymorphinan (3HM). In neonates and children, a low level of CYP 3A4 causes decreased formation of 3MM and 3HM, resulting in elevated DX.61 We tested whether the time-embedding network correctly captures the age-dependent dynamics of CYP2D6 and 3A4 expression that lead to these observed clinical effects by developing a simplified pharmacokinetic model to predict increased or decreased metabolite exposure, relative to adults (Data and Methods). Briefly, this model assumes linear kinetics, and a rough equivalence of reaction rates for all reactions in adults. Thus, the model’s rate parameters can be estimated by the fraction of adult enzyme expression for each enzyme catalyzing a given reaction. The result is a system of linear differential equations, which can be solved for steady state metabolite concentrations for both adult enzyme levels and child enzyme levels. We report the ratio of predicted substrate concentration in children to that of adults. This simplified model correctly predicted that exposure to DX is increased and exposure to both 3MM and 3HM are decreased in 7 day old neonates relative to adults (Figure 10B).

Figure 10: Combining metabolism ontogeny models with a simple pharmacokinetics model and the XenoSite reactivity model reveals age-dependent changes in reactive metabolite exposure.

(A,B) Modeling the relative abundance of dextromethorphan metabolites as a function of age reflects trends observed in clinical data, which suggest that children have increased levels of dextrorphan metabolites and decreased levels of methoxymorphinan, relative to adults. (C) Valproic acid (VPA) is a known hepatoxic drug with several covalently reactive metabolites including 4-ene VPA (2), and 2,4-diene VPA (3). The XenoSite reactivity model identifies 2,4-diene-VPA as a strongly reactive, and potentially toxic metabolite of valproic acid (VPA). (D) Modeling the relative abundance of VPA metabolites as a function of age suggests that children may have increased exposure to 2,4-diene VPA.

Age-dependent exposure to reactive metabolites of valproic acid

Reactive metabolites are an important cause of drug toxicity in the clinic. Previous modeling efforts have produced robust models of reactive metabolite formation and reactivity with biological molecules and scavenger probes.42,43 Combining these models with predictions of age-dependent changes in metabolite exposure may enable scientists to quickly identify mechanisms of toxicity and potential age-dependent risks. To test this approach, we analyzed valproic acid, a drug with known reactive metabolites and a risk of hepatotoxicity, to which children are especially susceptible62.63

The ontogeny model, combined with pharmacokinetics and reactivity models, hypothesizes age-dependent changes in reactive metabolite exposure for valproic acid (VPA). The metabolism of VPA involves multiple systems, including CYPs, UGTs and GST (Figure 10C).64 We first applied the XenoSite reactivity model42,43 to each of the metabolites of VPA. 2,4-Diene VPA is a known reactive metabolite of VPA and appropriately received the highest reactivity score (0.62). We next applied the same simplified pharmacokinetic modeling approach used to analyze dextromethorphan above. As a fatty acid, VPA undergoes β-oxidation reactions in the mitochondria, which give rise to several unsaturated metabolites. For our model we assumed that β-oxidation rates were not influenced by age. The model predicts increased exposure to both 2,4-diene VPA and 3-hydroxy VPA in 7 day old neonates. The direct precursor of 2,4-diene VPA is 4-ene VPA, and its serum levels are detected in young children treated for epilepsy with multiple pharmacological agents.65 This possible route to reactive the direct precursor of 2,4-diene VPA may contribute to hepatotoxicity in young children, although the exact mechanism remains unknown. Furthermore, druginduced changes in metabolism likely play an important role in the metabolite profile of valproic acid, since valproic acid is commonly co-administered with other anti-epileptics. For example, increased serum levels of 4-ene VPA have been detected in young children treated for epilepsy with valproic acid in addition to carbemazepine or phenytoin.66,67 Valproic acid metabolism is complex and confounded by clinically important drug interactions. The combination of our ontogeny model with current advanced PBPK models would likely produce a more robust prediction of age-dependent metabolite exposure for assessing drug toxicity risks.

Limitations and Future Work

The approach to ontogeny modeling we have presented has some important limitations. First, while the 23 hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes modeled in this work cover a substantial portion of those involved in drug metabolism, many more enzymes are also implicated in clinically important drug reactions such as epoxide hydrolase,68 aldehyde oxidases,69 UGT1A and UGT2A enzymes.70 Furthermore, the dataset we used underrepresented important ethnic groups, such as Asian Americans, and did not include adequate samples to estimate the expression effects of genetic polymorphisms. New high-throughput techniques for collecting data on human hepatic drug metabolizing enzyme expression, such as liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS), may enable construction of more comprehensive and densely sampled datasets for training time-embedding models. At the time of this study, an LCMS dataset comparable in sample size and number of measured enzymes was not readily available to us. In contrast, the data used in this study are publicly available.22 Second, the simplified kinetic model we use in this work assigned reactions to only kinetically favorable enzymes and assumed that base clearance rates in adults were identical for all the metabolic transformations of a given drug and its metabolites. This kinetic model will incorrectly estimate ontogeny effects in some cases. Potential improvements could be obtained by combining our ontogeny model with more sophisticated PBPK modeling to better estimate metabolite exposure. Finally, this modeling approach still requires collecting experimental or literature data on metabolic reactions, metabolite structures and pharmacokinetics to estimate exposure to toxic metabolites. Multiple groups are actively pursuing in silico solutions to predict these data,71–73 which could be combined with our ontogeny and reactivity models to create an in silico pipeline for estimating toxic metabolite exposure risks.

In future works, our ontogeny modeling approach can be straightforwardly adapted to improve predictions of age-dependent metabolite exposures. In particular, four useful extensions are immediately possible. First, a sampling approach to enable identification and estimation of the size of subpopulations with similar metabolite profiles could be developed using the population-level expression distributions produced by the ontogeny model. This may enable researchers to identify subpopulations whose metabolite profiles put them at higher risk of toxicity. Second, modeling covariance among the enzymes in the ontogeny model would improve population-level distribution estimates and improve the feasibility of the previous extension. Modeling covariance would improve the correspondence between samples drawn from the expression distributions and human populations, but a larger training dataset would likely be required to achieve accurate covariance estimates. Third, combining the ontogeny model with more accurate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics models may yield a robust and physiologically accurate system for predicting age-dependent metabolite exposures. Finally, we anticipate that the methods we have presented will be valuable in analyzing larger and more comprehensive LCMS datasets in the future.

Conclusion

In this study, we focused on two main scientific goals. First, (1) we developed the most comprehensive model of hepatic drug metabolism ontogeny available in the literature. We modeled the ontogeny of 23 drug metabolizing enzymes, encompassing key enzymes of both phase I and II metabolism involved in metabolizing the majority of FDA approved drugs. We achieved this goal by introducing a new neural network component, the time-embedding network, which improved on a straight-forward neural network approach by both improving overall accuracy, reducing the number of required parameters, capturing complex time-dependent patterns in the data such as are observed with CYP2D6, and correctly identifying the effect of demographics on 3A enzyme expression. The model estimated age-dependent, population-level distributions in enzyme expression, to enable the study of population exposures to drug metabolites. Second, (2) we have shown how this ontogeny model can be combined with simple pharmacokinetic modeling to explain clinical observations of age-dependent metabolism and drug toxicity. Specifically, we demonstrated that population-level ontogeny models can explain observed patterns of metabolism and metabolite exposure for tramadol and dextromethorphan. Furthermore, we showed how this ontogeny model could be combined with models of metabolite reactivity to estimate age-dependent exposure to reactive metabolites of valproic acid. This combined approach could be used assess drug toxicity risk in the pre-clinical phases of drug development. We are optimistic that this modeling approach may be used to support the design of safe drugs and drug trials for pediatric patients.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1: The time-embedding network identifies age-dependent patterns among many variables, reducing them to an interpretable, low-dimensional, sparsely-sampled embedding.

The time-embedding forms the backbone of the model. The time-embedding is a matrix of column-vectors comprising discrete, sparsely sampled points interpolated over time. Samples from the interpolated time-embedding are combined with time-independent control variables and passed to a decoder network, which is a neural network two adjacent hidden layers and three adjacent output layers. This neural network is trained to output log-normal mixture distributions that maximize the likelihood of the observed expression data. The time-embedding features are learned simultaneously while training the decoder network by backpropagation.

Figure 5: A subset of four of the 23 modeled enzymes qualitatively demonstrates that the time-embedding network captures age-dependent, population-level distributions in metabolism enzyme expression.

Blue lines and error bars show the model predicted mean expression and standard deviation, while grey triangles show measured expression in liver samples. Model predictions between conception and age 18 were binned into the same age groups used during modeling, and the mean and standard deviation of the joint distribution was plotted (Data and Methods). Inset plots show model predicted detection rates (blue circles) and detection rates calculated from the data (grey bars). Age axis is plotted on a semilog scale (Data and Methods).

Synopsis:

A new neural network structure designed to capture time-dependent patterns models hepatic drug metabolizing enzyme development. This modeling approach is combined with previously developed models of small-molecule reactivity and literature metabolism data to model age-dependent exposure to toxic drug metabolites.

Acknowledgement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial conflicts of interests. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Library Of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01LM012222 and R01LM012482, and by the National Institutes of Health under Award Number GM07200. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Computations were performed using the facilities of the Washington University Center for High Performance Computing, which were partially funded by NIH grants nos. 1S10RR022984-01A1 and 1S10OD018091-01. We also thank both the Department of Immunology and Pathology at the Washington University School of Medicine, the Washington University Center for Biological Systems Engineering and the Washington University Medical Scientist Training Program for their generous support of this work.

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the receiver operator curve

- CES

carboxylesterase enzyme family

- CYP

cytochrome P450 enzyme family

- FMO

flavin mono-oxygenase enzyme family

- GSTZ

glutathione transferase enzyme family

- NN

neural network

- RMSE

root mean squared error

- SULT

sulfur transferase enzyme family

- UGT

uridine-glucuronosyl transferase enzyme family

- TE

time-embedding

Footnotes

- Supplementary information: supplementary figures S1–6, supplementary table S1

- Supplemental Data.xlsx: tramadol clearance data and model from Allegaert et al, five predicted age-dependent expression distributions for the 23 modeled enzymes (male, female, Caucasian, African American, premature births)

References

- (1).Rodríguez-Mongui R; Otero MJ; Rovira J Assessing the Economic Impact of Adverse Drug Effects. PharmacoEconomics 2003, 21, 623–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).White TJ; Arakelian A; Rho JP Counting the costs of drug-related adverse events. Pharmacoeconomics 1999, 15, 445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Pirmohamed M; James S; Meakin S; Green C; Scott AK; Walley TJ; Farrar K; Park BK; Breckenridge AM Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ 2004, 329, 15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Knowles SR; Uetrecht J; Shear NH Idiosyncratic drug reactions: the reactive metabolite syndromes. The Lancet 2000, 356, 1587–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Park BK; Boobis A; Clarke S; Goldring CEP; Jones D; Kenna JG; Lambert C; Laverty HG; Naisbitt DJ; Nelson S; Nicoll-Griffith DA; Obach RS; Routledge P; Smith DA; Tweedie DJ; Vermeulen N; Williams DP; Wilson ID; Baillie TA Managing the challenge of chemically reactive metabolites in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2011, 10, 292–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gonzalez FJ Role of cytochromes P450 in chemical toxicity and oxidative stress: studies with CYP2E1. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2005, 569, 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Chen W; Koenigs LL; Thompson SJ; Peter RM; Rettie AE; Trager WF; Nelson SD Oxidation of Acetaminophen to Its Toxic Quinone Imine and Nontoxic Catechol Metabolites by Baculovirus-Expressed and Purified Human Cytochromes P450 2E1 and 2A6. Chem. Res. Toxicol 1998, 11, 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Iverson SL; Uetrecht JP Identification of a Reactive Metabolite of Terbinafine: Insights into Terbinafine-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2001, 14, 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).l. Lin H; Kenaan C; Hollenberg PF Identification of the Residue in Human CYP3A4 That Is Covalently Modified by Bergamottin and the Reactive Intermediate That Contributes to the Grapefruit Juice Effect. Drug Metab. Dispos 2012, 40, 998–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zhang F; Fan PW; Liu X; Shen L; van Breemen RB; Bolton JL Synthesis and Reactivity of a Potential Carcinogenic Metabolite of Tamoxifen: 3, 4-Dihydroxytamoxifen- o -quinone. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2000, 13, 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Han X; Liehr JG Induction of covalent DNA adducts in rodents by tamoxifen. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 1360–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Guengerich FP Cytochrome P450s and other enzymes in drug metabolism and toxicity. The AAPS Journal 2006, 8, E101–E111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Jancova P; Anzenbacher P; Anzenbacherova E Phase II drug metabolizing enzymes. Biomed. Pap 2010, 154, 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Cerny MA Prevalence of Non-Cytochrome P450-Mediated Metabolism in Food and Drug Administration-Approved Oral and Intravenous Drugs: 2006–2015. Drug Metab. Dispos 2016, 44, 1246–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Chasseaud L Advances in Cancer Research; Elsevier, 1979; pp 175–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Mitchell J; Jollow D; Potter W; Gillette J; Brodie B Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. IV. Protective role of glutathione. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1973, 187, 211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hoppu K; Anabwani G; Garcia-Bournissen F; Gazarian M; Kearns GL; Nakamura H; Peterson RG; Ranganathan SS; de Wildt SN The status of paediatric medicines initiatives around the world—what has happened and what has not? European journal of clinical pharmacology 2012, 68, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sultana J; Cutroneo P; Trifirò G Clinical and economic burden of adverse drug reactions. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother 2013, 4, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Milne C-P; Bruss JB The economics of pediatric formulation development for offpatent drugs. Clin. Ther 2008, 30, 2133–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Sage DP; Kulczar C; Roth W; Liu W; Knipp GT Persistent pharmacokinetic challenges to pediatric drug development. Front. Genet 2014, 5, 281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).de Wildt SN; Tibboel D; Leeder J Drug metabolism for the paediatrician. Archives of disease in childhood 2014, 99, 1137–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).McCarver DG; Simpson PM; Kocarek TA; James MO; Runge-Morris M; Stevens JC; Yoon M; Hines R Data from: Developmental expression of drug metabolizing enzymes: impact on disposition in neonates and young children. 2017; https://datadryad.org/resource/ doi: 10.5061/dryad.71pp6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- (23).Song G; Sun X; Hines RN; McCarver DG; Lake BG; Osimitz TG; Creek MR; Clewell HJ; Yoon M Determination of human hepatic CYP2C8 and CYP1A2 Age-dependent expression to support human health risk assessment for early ages. Drug Metab. Dispos 2017, 45, 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Croom EL; Stevens JC; Hines RN; Wallace AD; Hodgson E Human hepatic CYP2B6 developmental expression: the impact of age and genotype. Biochem. Pharmacol 2009, 78, 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Koukouritaki SB; Manro JR; Marsh SA; Stevens JC; Rettie AE; McCarver DG; Hines RN Developmental expression of human hepatic CYP2C9 and CYP2C19. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2004, 308, 965–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Stevens JC; Marsh SA; Zaya MJ; Regina KJ; Divakaran K; Le M; Hines RN Developmental changes in human liver CYP2D6 expression. Drug Metab. Dispos 2008, 36, 1587–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Johnsrud EK; Koukouritaki SB; Divakaran K; Brunengraber LL; Hines RN; McCarver DG Human hepatic CYP2E1 expression during development. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2003, 307, 402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Stevens JC; Hines RN; Gu C; Koukouritaki SB; Manro JR; Tandler PJ; Zaya MJ Developmental expression of the major human hepatic CYP3A enzymes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2003, 307, 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hines RN; Simpson PM; McCarver DG Age-dependent human hepatic carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) and carboxylesterase 2 (CES2) postnatal ontogeny. Drug Metab. Dispos 2016, 44, 959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Koukouritaki SB; Simpson P; Yeung CK; Rettie AE; Hines RN Human hepatic flavin-containing monooxygenases 1 (FMO1) and 3 (FMO3) developmental expression. Pediatr. Res 2002, 51, 236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Zaya MJ; Hines RN; Stevens JC Epirubicin glucuronidation and UGT2B7 developmental expression. Drug Metab. Dispos 2006, 34, 2097–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Divakaran K; Hines RN; McCarver DG Human hepatic UGT2B15 developmental expression. Toxicol. Sci 2014, 141, 292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Li W; Gu Y; James MO; Hines RN; Simpson P; Langaee T; Stacpoole PW Prenatal and postnatal expression of glutathione transferase ζ 1 in human liver and the roles of haplotype and subject age in determining activity with dichloroacetate. Drug Metab. Dispos 2012, 40, 232–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Duanmu Z; Weckle A; Koukouritaki SB; Hines RN; Falany JL; Falany CN; Kocarek TA; Runge-Morris M Developmental expression of aryl, estrogen, and hydroxysteroid sulfotransferases in pre-and postnatal human liver. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2006, 316, 1310–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Baldi P; Long AD A Bayesian framework for the analysis of microarray expression data: regularized t-test and statistical inferences of gene changes. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lu P; Vogel C; Wang R; Yao X; Marcotte EM Absolute protein expression profiling estimates the relative contributions of transcriptional and translational regulation. Nat. Biotechnol 2007, 25, 117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kendziorski C; Newton M; Lan H; Gould M On parametric empirical Bayes methods for comparing multiple groups using replicated gene expression profiles. Stat. Med 2003, 22, 3899–3914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Ngiam J; Coates A; Lahiri A; Prochnow B; Le QV; Ng AY On optimization methods for deep learning. Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-11) 2011; pp 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zhang GP Neural networks for classification: a survey. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2000, 30, 451–462. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Swamidass SJ; Calhoun BT; Bittker JA; Bodycombe NE; Clemons PA Enhancing the rate of scaffold discovery with diversity-oriented prioritization. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2271–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Sadeque AJ; Fisher MB; Korzekwa KR; Gonzalez FJ; Rettie AE Human CYP2C9 and CYP2A6 mediate formation of the hepatotoxin 4-ene-valproic acid. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1997, 283, 698–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hughes TB; Miller GP; Swamidass SJ Site of Reactivity Models Predict Molecular Reactivity of Diverse Chemicals with Glutathione. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2015, 28, 797–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hughes TB; Dang NL; Miller GP; Swamidass SJ Modeling Reactivity to Biological Macromolecules with a Deep Multitasking Network. ACS Cent. Sci 2016, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kitada M Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 enzymes in Asian populations: focus on CYP2D6. International journal of clinical pharmacology research 2003, 23, 31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Hines RN The ontogeny of drug metabolism enzymes and implications for adverse drug events. Pharmacol. Ther 2008, 118, 250–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Hakkola J; Tanaka E; Pelkonen O Developmental Expression of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Human Liver. Pharmacology & Toxicology 1998, 82, 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Rich KJ; Boobis AR Expression and inducibility of P450 enzymes during liver ontogeny. Microsc. Res. Tech 1997, 39, 424–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Lacroix D; Sonnier M; Moncion A; Cheron G; Cresteil T Expression of CYP3A in the Human Liver - Evidence that the Shift between CYP3A7 and CYP3A4 Occurs Immediately After Birth. Eur. J. Biochem 1997, 247, 625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Hornik K; Stinchcombe M; White H Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural networks 1989, 2, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Kuehl P; Zhang J; Lin Y; Lamba J; Assem M; Schuetz J; Watkins PB; Daly A; Wrighton SA; Hall SD; Maurel P; Relling M; Brimer C; Yasuda K; Venkataramanan R; Strom S; Thummel K; Boguski MS; Schuetz E Sequence diversity in CYP3A promoters and characterization of the genetic basis of polymorphic CYP3A5 expression. Nat. Genet 2001, 27, 383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Johnson TN; Rostami-Hodjegan A; Tucker GT Prediction of the clearance of eleven drugs and associated variability in neonates, infants and children. Clin. Pharmacokinet 2006, 45, 931–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Salem F; Johnson TN; Abduljalil K; Tucker GT; Rostami-Hodjegan A A Reevaluation and Validation of Ontogeny Functions for Cytochrome P450 1A2 and 3A4 Based on In Vivo Data. Clin. Pharmacokinet 2014, 53, 625–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Subrahmanyam V; Renwick AB; Walters DG; Young PJ; Price RJ; Tonelli AP; Lake BG Identification of cytochrome P-450 isoforms responsible for cis-tramadol metabolism in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos 2001, 29, 1146–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Allegaert K; Anderson B; Verbesselt R; Debeer A; de Hoon J; Devlieger H; Anker JVD; Tibboel D Tramadol disposition in the very young: an attempt to assess in vivo cytochrome P −450 2D6 activity. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2005, 95, 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Allegaert K; Rochette A; Veyckemans F Developmental pharmacology of tramadol during infancy: ontogeny, pharmacogenetics and elimination clearance. Pediatric Anesthesia 2010, 21, 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Grond S; Meuser T; Uragg H; Stahlberg HJ; Lehmann KA Serum concentrations of tramadol enantiomers during patient-controlled analgesia. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 2001, 48, 254–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Lai J; wu Ma S; Porreca F; Raffa RB Tramadol, M1 metabolite and enantiomer affinities for cloned human opioid receptors expressed in transfected HN9.10 neuroblastoma cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol 1996, 316, 369–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Allegaert K; den Anker JNV; Verbesselt R; de Hoon J; Vanhole C; Tibboel D; Devlieger H O-demethylation of tramadol in the first months of life. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2005, 61, 837–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Accessed October, 2018, https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer.

- (60).Kerry N; Somogyi A; Bochner F; Mikus G The role of CYP2D6 in primary and secondary oxidative metabolism of dextromethorphan: in vitro studies using human liver microsomes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 1994, 38, 243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Blake M; Gaedigk A; Pearce R; Bomgaars L; Christensen M; Stowe C; James L; Wilson J; Kearns G; Leeder J Ontogeny of Dextromethorphan O-and N-demethylation in the First Year of Life. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 2007, 81, 510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).de Wildt SN Profound changes in drug metabolism enzymes and possible effects on drug therapy in neonates and children. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol 2011, 7, 935–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Dreifuss FE; Langer DH Hepatic considerations in the use of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia 1987, 28, S23–S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Ghodke-Puranik Y; Thorn CF; Lamba JK; Leeder JS; Song W; Birnbaum AK; Altman RB; Klein TE Valproic acid pathway. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 2013, 23, 236–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Siemes H; Nau H; Schultze K; Wittfoht W; Drews E; Penzien J; Seidel U Valproate (VPA) Metabolites in Various Clinical Conditions of Probable VPA-Associated Hepatotoxicity. Epilepsia 1993, 34, 332–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Levy RH; Rettenmeier AW; Anderson GD; Wilensky AJ; Friel PN; Baillie TA; Acheampong A; Tor J; Guyot M; Loiseau P Effects of polytherapy with phenytoin, carbamazepine, and stiripentol on formation of 4-ene-valproate, a hepatotoxic metabolite of valproic acid. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 1990, 48, 225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Kondo T; Kaneko S; Otani K; Ishida M; Hirano T; Fukushima Y; Muranaka H; Koide N; Yokoyama M Associations between risk factors for valproate hepatotoxicity and altered valproate metabolism. Epilepsia 1992, 33, 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Spina E; Pisani F; Perucca E Clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with carbamazepine. Clin. Pharmacokinet 1996, 31, 198–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Obach RS; Huynh P; Allen MC; Beedham C Human liver aldehyde oxidase: inhibition by 239 drugs. J. Clin. Pharmacol 2004, 44, 7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Kiang TK; Ensom MH; Chang TK UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and clinical drug-drug interactions. Pharmacol. Ther 2005, 106, 97–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Djoumbou-Feunang Y; Fiamoncini J; Gil-de-la Fuente A; Greiner R; Manach C; Wishart DS BioTransformer: a comprehensive computational tool for small molecule metabolism prediction and metabolite identification. J. Cheminf 2019, 11, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Barnette D; Davis M; Dang L; Swamidass SJ; Miller G Lamisil (terbinafine): determining bioactivation pathways using computational modeling and experimental approaches. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet 2019, 34, S57. [Google Scholar]

- (73).Dang NL; Hughes TB; Miller GP; Swamidass SJ Computationally Assessing the Bioactivation of Drugs by N-Dealkylation. Chem. Res. Tox 2018, 31, 68–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.