Abstract

Atherosclerosis is associated with a compromised endothelial barrier, facilitating the accumulation of immune cells and macromolecules in atherosclerotic lesions. In this study, we investigate endothelial barrier integrity and the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect during atherosclerosis progression and therapy in Apoe–/– mice using hyaluronan nanoparticles (HA-NPs). Utilizing ultrastructural and en face plaque imaging, we uncover a significantly decreased junction continuity in the atherosclerotic plaque-covering endothelium compared to the normal vessel wall, indicative of disrupted endothelial barrier. Intriguingly, the plaque advancement had a positive effect on junction stabilization, which correlated with a 3-fold lower accumulation of in vivo administrated HA-NPs in advanced plaques compared to early counterparts. Furthermore, by using super-resolution and correlative light and electron microscopy, we trace nanoparticles in the plaque microenvironment. We find nanoparticle-enriched endothelial junctions, containing 75% of detected HA-NPs, and a high HA-NP accumulation in the endothelium-underlying extracellular matrix, which suggest an endothelial junctional traffic of HA-NPs to the plague. Finally, we probe the EPR effect by HA-NPs in the context of metabolic therapy with a glycolysis inhibitor, 3PO, proposed as a vascular normalizing strategy. The observed trend of attenuated HA-NP uptake in aortas of 3PO-treated mice coincides with the endothelial silencing activity of 3PO, demonstrated in vitro. Interestingly, the therapy also reduced the plaque inflammatory burden, while activating macrophage metabolism. Our findings shed light on natural limitations of nanoparticle accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques and provide mechanistic insight into nanoparticle trafficking across the atherosclerotic endothelium. Furthermore, our data contribute to the rising field of endothelial barrier modulation in atherosclerosis.

Keywords: nanomedicine, atherosclerosis, enhanced permeability and retention effect, endothelial normalization, vascular endothelial cadherin

Nanomedicine applies nanotechnology tools to aid in disease management. Therapeutic and diagnostic benefits of long-circulating nanoparticles rely on their ability to reach the disease site at high efficacy and selectivity, which has been demonstrated in animal models of cancer, atherosclerosis, and autoimmune diseases.1−5 This lesion-favorable biodistribution has been attributed to the compromised endothelial barrier and impaired lymphatic drainage, often referred to as the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.6 Clinical evidence of the EPR effect has been provided by several imaging studies, predominantly, for radiolabeled liposomes.7,8 However, the accumulation of clinical trial data shed light on the inter- and intratumor heterogeneity of the EPR effect in human tumors,9−11 which has been overseen by, and underinvestigated in, earlier preclinical studies. Recently, nanomedicine entered cardiovascular medicine.12,13 One of the key findings of a small trial by van der Valk et al.12 is the uptake of intravenously administrated long-circulating liposomes by macrophages of human atherosclerotic lesions, which supports the preceding preclinical observations.2 Our present study focuses on the identification of intrinsic and acquired limitations of nanoparticle performance in atherosclerosis and understanding the mechanism(s) driving nanoparticle accumulation at the lesion site.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease, characterized by the formation of lipid-rich lesions (plaques) in the vessel wall14 and compromised endothelial barrier.15 In recent years, nanoparticle-based strategies for diagnosis and treatment of atherosclerosis have emerged,5 aimed predominantly at the plaque inflammation. It is important that feasibility studies include the context of the natural lesion progression, which is associated with a considerable microenvironmental diversification, including the lipid buildup, immune cell recruitment, foam cell formation, collagen deposition, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and necrotic core formation. Notably, in an individual atherosclerosis patient, we can find lesions at different stages of development.16,17 We have addressed the aspect of lesion diversity in our recent report on hyaluronan nanoparticles (HA-NPs), which showed high selectivity in targeting plaque-associated macrophages in mice, but, interestingly, they were 6-fold less effectively taken up by macrophages in advanced plaques compared to early lesions.18 To explain this striking difference, we here investigate the impact of disease progression on the integrity of atherosclerotic endothelium and the concomitant plaque-homing efficacy and intraplaque distribution of HA-NPs. Furthermore, we use our nanoparticle platform to probe the EPR effect in a therapeutic setting, which aims at the normalization of atherosclerotic endothelium and which is inspired by recent findings on the tumor vessel normalization by glycolysis inhibition.19 The endothelial barrier-related effects are studied jointly with the arterial glycolytic activity and plaque inflammatory burden.

The aforementioned aims cannot be fully reached without understanding the mechanistic aspect of nanoparticle homing to atherosclerotic lesions. In the current literature, the selectivity and efficacy of nanomaterials to atherosclerotic lesions have primarily been attributed to the enhanced permeability of plaque neovasculature,20−22 yet these are mostly absent in murine lesions and highly heterogeneous in human plaques. However, nanoparticle plaque accumulation may potentially occur via different routes, that is, the plaque-covering macrovascular endothelium or microvasculature running through the plaque. Transendothelial crossing of NPs may be para- or transcellular, and blood leukocytes might be involved as transporters.23−25 As few reports address this aspect of nanomedicine, we recently published on the targeting mechanism of long-circulating liposomes in rabbit atherosclerosis, showing a significant correlation between the early accumulation level of liposomes and aortic endothelial permeability.21

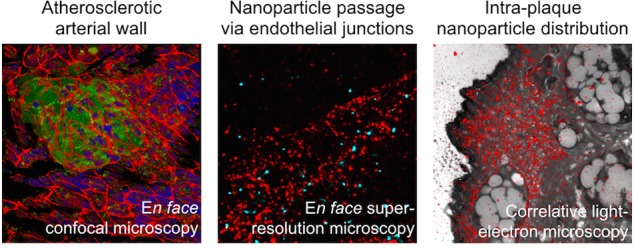

In this paper, we study endothelial barrier integrity in atherosclerosis development and progression and its impact on plaque targetability by HA-NPs. The experiments were performed in Apoe–/– mice, with either early or advanced atherosclerosis.26En face visualization of vascular endothelial cadherin (VEC), one of the key endothelial cell–cell junction proteins that forms the endothelial barrier,27,28 was investigated in atherosclerotic aorta by confocal microscopy. This was corroborated by the readout of HA-NP plaque-homing efficacy. Subsequently, the endothelial junction ultrastructure was studied by advanced microscopy methods, including the two-color super-resolution microscopy and correlative light and electron microscopy to unveil the trafficking pathways of HA-NPs to atherosclerotic lesions. Finally, we evaluate the endothelial and inflammatory effects of metabolic therapy with 3PO, a small-molecule glycolysis inhibitor,19 in atherosclerotic mice. HA-NPs and a fluorescent glucose analogue, 2-NBDG, were used to probe the aortic endothelial barrier function and metabolic (glycolytic) activity, respectively. This was complemented by histological analyses of the plaque inflammatory burden and hypoxia.

Results and Discussion

Experimental Setup

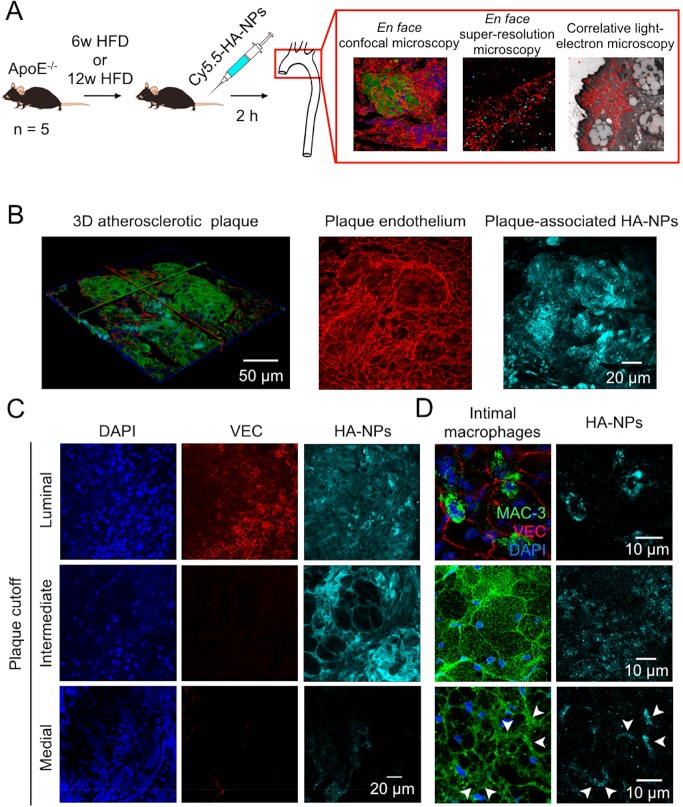

To investigate the relation between the vascular endothelial barrier integrity and HA-NP plaque targetability in the atherosclerotic plaque progression, Apoe–/– mice were put on a 6- or 12-week high-fat diet (HFD) to develop early or advanced atherosclerotic lesions, respectively (n = 5/group). Two h before sacrifice, the mice received an intravenous (i.v.) injection of Cy5.5-labeled HA-NPs. The chosen time point post-HA-NP administration was based on the previously reported correlation between early accumulation levels of long-circulating nanoparticles and plaque permeability.21 The correlation was strong at 30 min and 6 h and became non-significant at 24 h post-administration, which we attributed to the intraplaque NP redistribution and cell internalization. Therefore, 2 h circulation time ensures detectable levels of plaque-associated HA-NPs interacting with the endothelium. The excised aortas were cut longitudinally to expose the luminal endothelium surface for immunofluorescence imaging, as described previously,29 and were stained for endothelial adherens junctions (vascular endothelial cadherin, VEC), macrophages (MAC-3), and nuclei (DAPI). Subsequently, the aortic arch samples were imaged by advanced microscopy methods, including confocal, super-resolution, electron, and correlative fluorescence and electron microscopy. Our experimental setup is outlined in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of experimental setup used to study atherosclerotic endothelial integrity. ApoE–/– mice were on either a 6-week or 12-week HFD to develop early or advanced atherosclerotic lesions, respectively. Subsequently, the mice received Cy5.5-labeled HA-NPs 2 h before their sacrifice. The excised aortic arches were fixed and cut longitudinally to expose luminal endothelial surface. The samples were stained and imaged en face by confocal and super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Furthermore, sections of aortic arches were investigated by electron microscopy and correlative super-resolution fluorescence and electron microscopy. (B) Representative confocal microscopy data obtained by en face analysis of the aortic arch of an Apoe–/– mouse after 6 weeks HFD. 3D visualization of an early atherosclerotic lesion (left image; MAC-3: green, VEC: red, DAPI: blue, HA-NPs: cyan blue). MIP of the luminal surface of the same atherosclerotic plaque with the VEC-stained endothelium (middle image) and the corresponding MIP of the entire plaque volume displaying HA-NP fluorescence (left image). (C) Heterogeneity of intraplaque distribution of HA-NPs in mice after 6-week HFD. The images represent luminal (upper), intermediate (middle), and medial (lower) sections of atherosclerotic plaque. The changes in the plaque cellularity can be deduced from DAPI staining (blue, left panel), whereas the presence of vascular endothelium is visualized by VEC staining (red, middle). In the right panel, the intraplaque distribution of HA-NP fluorescence (cyan blue) can be followed. It changes from relatively homogeneous at the plaque surface to focal in the intermediate plaque compartment and finally disappears at the media. (D) The HA-NP uptake (cyan blue, right) by intimal macrophages (green, left). Upper panel displays single, presumably recently recruited macrophages in the aortic intima, which contain high levels of internalized HA-NPs. The middle and lower images display macrophages/foam cells found superficially and in deeper compartments of established atherosclerotic lesions, receptively. The former internalized efficiently HA-NPs, whereas the latter had only HA-NP-positive cell margins.

En Face Visualization of Atherosclerotic Plaques and Plaque-Associated Hyaluronan Nanoparticles

To study the relation between the plaque endothelial barrier integrity and HA-NP accumulation, we performed en face confocal microscopy of aortic samples. En face analysis enabled us to assess multiple lesions per animal, that is, approximately 4 lesions/mouse, and to acquire the entire plaque volume as well as the underlying media. Figure 1B displays the representative three-dimensional (3D) visualization of early atherosclerotic plaque (left image) and the corresponding maximum intensity projection (MIP) of the VEC-stained plaque endothelial surface (middle image) and HA-NP uptake (right image). The latter image shows a high affinity and selectivity of HA-NPs to atherosclerotic plaque foci. Based on the image z-stacks, we could follow the intraplaque distribution of HA-NPs. As presented in Figure 1C, HA-NP fluorescence was intense and rather homogeneous at the luminal plaque side (upper panel). At intermediate plaque sections, the HA-NP signal was more heterogeneous, that is, high accumulation in acellular areas (free from DAPI staining) and peri-cellular localization around large foam cells (macrophages that engulfed lipids) comprising the core of the atherosclerotic plaques (middle panel). In all studied early and advanced plaques, HA-NPs penetrated throughout the entire plaque depth, however no HA-NP fluorescence was detected in the underlying medial layer of the vessel wall (lower panel). The HA-NP interaction with intimal macrophages was dependent on the macrophage differentiation and their spatial localization in the plaque. The upper panel in Figure 1D depicts single macrophages, presumably recently recruited to the vessel intima, which had a high intracellular HA-NP signal (upper panel). In established plaques, the superficial (close to the vessel lumen) macrophages also internalized HA-NPs efficiently (middle panel). In contrast, in deeper areas with foam cells, HA-NP were confined to cell margins (lower panel). The macrophage-HA-NP overlay images are presented in Figure S1A. Figure S2 contains additional images explaining the imaging plane, plaque sectioning strategy, and spatial localization of HA-NPs within the vessel wall and plaque microenvironment.

The current data need to be considered in the context of HA-NPs’ physicochemical and biological properties, which we reported previously and are discussed below.18 HA-NPs, formulated by reacting amine-functionalized oligomeric hyaluronan (70 kDa) (HA) with cholanic ester, are approximately 90 nm in diameter, in a hydrated state, and display a stable morphology under hydrolytic conditions, as confirmed by atomic force, electron, and super-resolution microscopy. We have demonstrated their 3-fold higher uptake by pro-inflammatory (LPS-stimulated) macrophages, compared to naïve and anti-inflammatory (IL4-stimulated) counterparts, which was not found for non-formulated HA and dextran-based NPs. Furthermore, we investigated the involvement of HA-binding receptors: CD44, ICAM-1, LYVE-1, and RHAMM, in the HA-NP internalization. When endocytosis is impaired in vitro by performing the incubations at 4 °C, HA-NPs co-localized to a strong degree with CD44 expression at the macrophage cell membrane and only partially with ICAM-1 signal (Figure S3A,B). No co-localization was observed with either RHAMM or LYVE-1 (Figure S3C,D). Although flow cytometry analysis revealed no quantitative correlation between the expression levels of HA-binding epitopes and HA-NP uptake efficacy, the competition experiment with free HA showed a ca. 50% drop of HA-NP signal in pro-inflammatory macrophages. Our data suggest that both receptor-mediated and non-specific pathways are involved in the HA-NP cell trafficking, but establishing the exact identity of the target(s) and mechanism of delivery require further investigations.

In mice, 89Zr-labeled HA-NPs showed biexponential blood clearance kinetics with a short and long half-life of 0.5 and 9 h, respectively, and predominant accumulation in the liver and spleen at 10–20% ID/g (total injected dose/g). In early atherosclerosis, HA-NPs displayed a much stronger selectivity for lesion-associated macrophages, 6- and 40-fold higher mean fluorescence intensity compared to splenic and bone marrow macrophages, respectively. In contrast, control poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)-NPs had an approximately 3-fold higher affinity to splenic macrophages compared to the aortic counterparts. The cellular uptake levels of HA-NPs correlated significantly with the HA-binding efficacy and CD44 expression in aortic immune cell populations (Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.62 and 0.74, respectively). In advanced lesions, however, we found a decreasing role of HA receptor-HA-NP interactions and a 4-fold lower HA-NP uptake in plaque-associated macrophages. In a therapeutic study, we demonstrated that a 12-week treatment with HA-NPs induces atheroprotective effects by decreasing the immune cell infiltration in mouse aortic lesions, by approximately 50%. Furthermore, PET imaging in atherosclerotic rabbits revealed a similar kinetic behavior of 89Zr-HA-NP and their accumulation in aortic macrophages.

Structural and Functional Integrity of Atherosclerotic Endothelium during Disease Progression

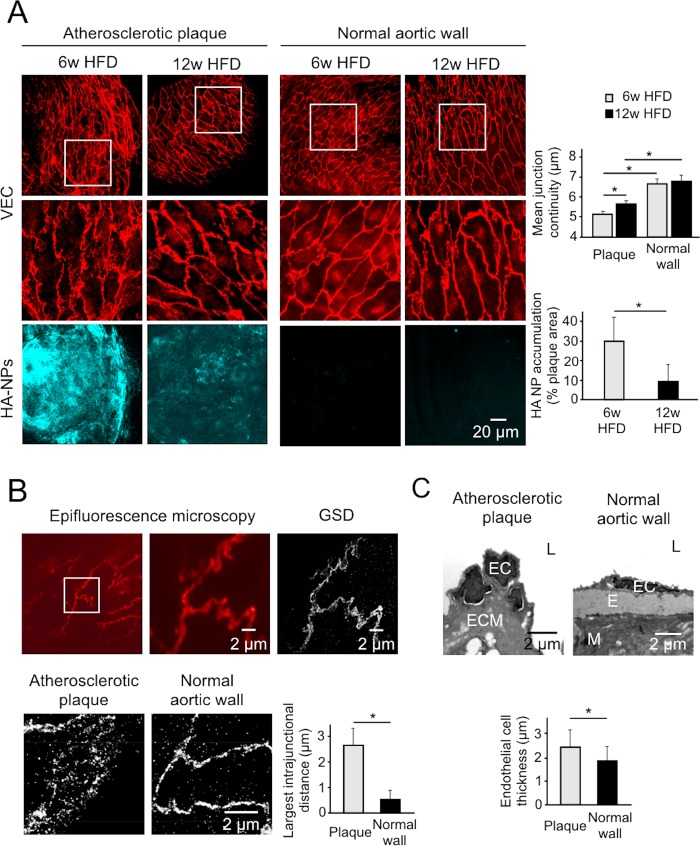

En face visualization technique was essential to determine the junction architecture of plaque-covering endothelium. The representative confocal MIPs of the endothelial surface of atherosclerotic and normal vessel walls are displayed in Figure 2A (upper and middle panels). In both early (6w HFD) and advanced (12w HFD) atherosclerosis groups, the normal vessel wall, that is, displaying no macrophage infiltration, was characterized by continuous junctions, which indicate a tight endothelial barrier.28 In contrast, VEC expression pattern of plaque endothelium was disorganized and frequently discontinued, indicative of endothelial activation and remodeling.30 The quantification of VEC continuity confirmed the disrupted endothelial junction organization in atherosclerotic lesions, that is, a ca. 20% lower VEC continuity compared to the normal vessel endothelium (Figure 2A, upper, right panel). Furthermore, by using ground-state depletion (GSD) super-resolution fluorescence microscopy, we could visualize the endothelial junction ultrastructure, as shown in Figure 2B. The atherosclerotic endothelial junctions displayed spaces between VEC units reaching up to 3 μm (Figure 2B, lower panel). In the normal endothelium, VEC molecules were tightly organized, and rarely observed spaces between junction units were approximately 0.5 μm. The abnormal and thickened cell morphology and junction abnormalities in atherosclerotic endothelium were further confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2C). Intriguingly, advanced plaques displayed a small but significant degree of endothelial normalization, as deduced from a significantly higher VEC continuity compared to early plaques (Figure 2A, upper, right panel). In line with this finding, advanced plaques were less accessible to i.v. administered HA-NPs, which were found in 10 ± 5% of plaque area and was significantly lower compared to 30 ± 10% of early plaques (Figure 2A, right, lower panel). The representative MIPs of HA-NP fluorescence in the entire plaque volume are displayed in Figure 2A (lower, left panel).

Figure 2.

(A) Comparison of the endothelial adherens junction architecture and HA-NP uptake efficacy in atherosclerotic lesions and normal vessel wall. Upper, left panel displays representative MIPs of VEC-stained endothelial junctions (red) in early (6w HFD) and advanced (12w HFD) atherosclerosis. The white frames depict regions of interest (ROIs) that are enlarged in the middle panel. The corresponding MIPs of HA-NP accumulation (cyan blue) in atherosclerotic plaques and a normal vessel wall are shown in the lower panel. In the right section, the upper chart displays the mean VEC continuity determined in the plaque and normal endothelium, and the lower chart shows the HA-NP uptake efficacy expressed as the fraction of HA-NP-positive plaque area. Gray and black bars represent early and late atherosclerosis, respectively. (B) The comparison of endothelial junction architecture of mouse aorta as visualized by epifluorescence microscopy (left and middle image) and GSD super-resolution fluorescence microscopy (right image) (upper panel). The lower images are representative for the ultrastructural organization of VEC-based junctions in atherosclerotic and normal aortic endothelium. In the example of atherosclerotic endothelial junction, large gaps between VEC molecules can be observed (left). In contrast, a normal aortic endothelium has tightly organized VEC (right). The right chart displays the largest intrajunction distance in the atherosclerotic endothelium compared to that of normal vessel wall (n = 13). (C) In the upper panel, TEM images display the altered endothelial cell morphology in atherosclerotic (left image) compared to normal endothelium (right image). Bar chart shows the endothelial cell thickness, measured in the nuclear cutoff of endothelial cells (bottom panel) (n = 44 and n = 29 for the plaque and normal vessel wall, respectively). L: lumen, E: elastin, ECM: extracellular matrix, M: media. In all charts, bars represent mean ± SD. Symbol “*” represents a significant difference at p < 0.05.

The negative impact of plaque progression on the accumulation efficacy of HA-NPs was also seen in our previous work,18 where we reported a 6-fold lower uptake of HA-NPs in advanced plaque-associated macrophages compared to early lesions, measured by flow cytometry. A similar pattern was observed by autoradiography of mouse aortas after administration of 89Zr-labeled HA-NPs. Previously, we attributed these differences to lower macrophage activity in advanced atherosclerosis. However, in the light of present findings, endothelial barrier remodeling might be an important contributing factor. Accordingly, early atherosclerotic events are associated with more severe endothelial barrier disruption compared to the advanced disease stage. As presented in Figure S1B, endothelial junction abnormalities were also observed in the presence of single intimal macrophages. Possibly, the observed endothelial normalization in advanced plaques is due to the endothelial adaptation to HFD-induced chronic inflammation.31 Additionally, an increased collagen production and smooth muscle cell proliferation, which occur in advanced plaques, might have a stabilizing effect on the endothelial barrier. A similar observation has previously been reported in atherosclerotic rabbits by Friedman and Byers et al.,32 who compared different HFD regimes. They concluded that excessive permeability of aortic intima ceases after fibrous healing or maturation of atherosclerotic plaque. Detailed analysis of magnetic resonance imaging study by Phinikaridou et al.,33 which probed atherosclerotic wall permeability at 8- and 12-weeks HFD by using an albumin-binding contrast agent, leads to similar conclusion. The vessel wall with early lesions displayed a similar mean post-contrast relaxation rate R1 compared to advanced lesions, which, considering a dramatically different lesion size, is indicative of a higher endothelial permeability in early atherosclerosis. This was also supported by the levels of extravasated albumin. Notably, however, there is a large fraction of human culprit lesions with endothelial erosion,34 which implies progressive endothelial damage.35 In this context, endothelial normalization strategies appear as an attractive therapeutic option.

In the current study, we quantitatively evaluated HA-NP plaque accumulation at 4 h post-administration (10 mice/group, Figure S4A). At this time point, the majority (more than 75%) of injected HA-NPs was cleared from the blood.18 This short circulation period resulted in the mean radiant efficiency (p/s/cm2/sr) of 6.6 × 107 ± 7.9 × 107 (early atherosclerosis) and 6.7 × 107 ± 1.3 × 107 (advanced atherosclerosis), which was significantly higher compared to the baseline signal in non-injected mice, that is, 3.2 × 106 ± 6.1 × 106 (p = 0.012 and p = 0.005 in early and advanced atherosclerosis, respectively). Previously, we performed corresponding experiments after allowing HA-NP to circulate for 24 h, at which low, but detectable levels of HA-NPs are still present in the circulation.18 In mice on a short-term diet, the prolonged circulation time did not result in a significant increase in HA-NP plaque accumulation compared to the 4 h time point, yielding 7.9 × 107 ± 3.1 × 107 fluorescence intensity (p = 0.86, compared to 4 h post-administration). In contrast, in animals with large advanced lesions, we did observe a plaque accumulation dependence with circulation time. Namely, the HA-NP signal has risen to 1.3 × 108 ± 4.0 × 107 (p = 0.0014, compared to 4 h time point).

The early atherosclerosis data indicate fast extravasation and plaque accumulation. Moreover, flow cytometry measurements uncovered efficient intraplaque redistribution of HA-NPs. Namely, we found a 3-fold higher level of HA-NP engulfment in plaque-associated macrophages at 24 h18 compared to 4 h time point (Figure S4B). We attribute this phenomenon to a highly permeable endothelial barrier, small plaque size, HA and proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix,36 and high phagocytic activity of resident macrophages. In contrast, large advanced plaques adopt a “tumor-like” accumulation profile, which benefits from long circulating NPs. In the latter case, both collagen and smooth muscle cells, which underlay endothelium and form up to 40–50% of plaque microenvironment, create structural barriers and slow down extravasating NPs. Similarly, in tumor lesions, the tissue morphology as well as heterogeneous blood supply were proposed as primary limiting factors of NP trafficking.37

Using the same experimental setup as described above, we visualized plaque neovasculature, that is, VEC-positive tubes running through the plaque (Figure S5). These were however rarely observed, that is, in ca. 10% of all lesions, in both the early and advanced atherosclerosis group, and in line with our CD31-based microvascular readout in aortic arch sections (Figure S6). Our data coincide with the previous findings by Moulton et al.,38 who also found a low incidence of lesion neovascularization in Apoe–/– mice. Interestingly, the plaque neovasculature that we observed was exclusively of the macrovascular origin, as deduced from its connectivity to the plaque-covering aortic endothelium and the microvessel-free media. Traditionally, the adventitial microvasculature was associated with angiogenic activation in atherosclerosis. The invasion of adventitial microvasculature into the lesion site has previously been demonstrated in several human histological studies.39,40 In atherosclerotic mice, intravital microscopy study by Eriksson et al.,41 and microcomputed tomography study by Langheinrich et al.42 demonstrated the microvascular enhancement in aortic adventitia associated with advanced atherosclerosis. Notably, however, both papers do not provide selective information on the lesion microvascular status, except for qualitative light or electron microscopy. On the other hand, Rademakers et al.43 showed that atherosclerosis-enhanced adventitial microvessels had no connectivity with the intraplaque neovasculature, which is in line with our findings. The advantage of our experimental setup in assessing the plaque microvascular status is the ability to visualize the entire plaque volume as well as the underlying tissue layers. The limitation might be, however, the penetration efficacy of the anti-VEC antibody through the tissue sample, which might be restricted in large, complex lesions. Previously, the relevance of plaque microvasculature has also been investigated in the context of the immune cell trafficking. Based on intravital microscopy, Eriksson et al.41 proposed the adventitial microvasculature as a primary trafficking pathway. However, Swirski et al.44 showed by histology that freshly recruited Ly-6Chigh monocytes are localized at the luminal plaque side, which corroborates our findings.

Trafficking Pathway(s) of Hyaluronan Nanoparticle to Atherosclerotic Lesions

The trafficking of systemically administered nanoparticles to atherosclerotic lesions is poorly understood. Several aspects need to be considered. First, both the macrovascular endothelium covering the plaque surface as well as intraplaque microvasculature might be involved. As demonstrated in the previous section, incidence of neovascularization in mouse lesions was very low, and therefore the luminal endothelial pathway was our primary focus. Second, NPs either can enter the plaque in their free form or can first be taken up by blood phagocytes and subsequently carried to the plaque. In our previous study, we observed a dramatically lower association of HA-NPs with newly recruited monocytes compared to differentiated plaque-associated macrophages,18 which supports the former hypothesis. Furthermore, the transfer of NPs across the endothelium can occur via either transcellular or paracellular pathways, which are both potentially relevant in activated endothelium.45

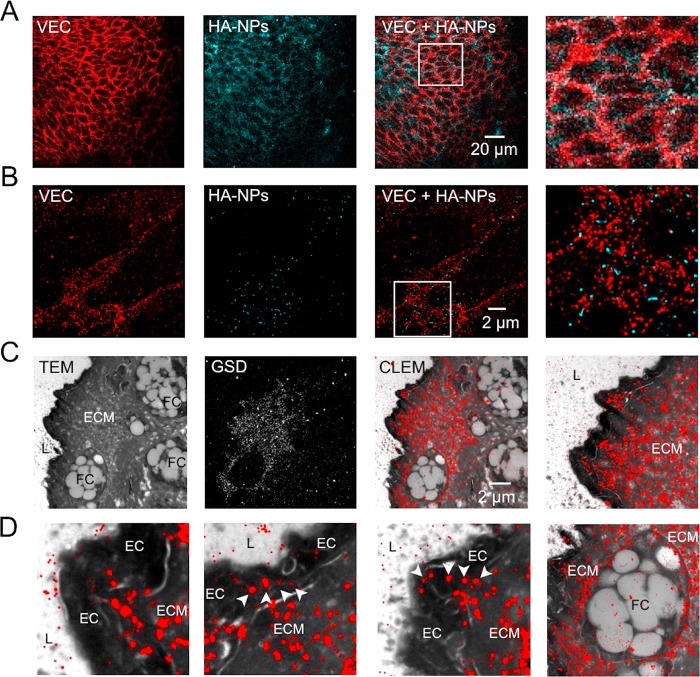

To address the aforementioned aspects of nanoparticle trafficking to atherosclerotic lesions, we first examined the luminal plaque surface by confocal microscopy. As displayed in Figure 3A, VEC-stained endothelial junctions (red, left) were enriched with HA-NP fluorescence (cyan blue, middle). However, as shown in the ROI (Figure 3A, fourth image), the spatial resolution was insufficient to certainly identify the extra- or intracellular localization of HA-NPs. To overcome this limitation, we investigated the HA-NP-endothelium interactions by two-color super-resolution GSD microscopy, which enabled us to spatially resolve HA-NPs and to assess them in context of the endothelial junction nanoarchitecture. Figure 3B displays en face organization of VEC molecules (red) in 18 × 18 μm2 field of view (first image) of mouse aorta after 6-week HFD. VEC units were loosely arranged within the endothelial cell junction (Figure 3B, first and last images), which is in line with the Figure 2B data. HA-NPs (cyan blue, second image), appearing as spherical structures of ∼100 nm in diameter, were predominantly associated with junctions, as deduced from the overlay image (third and fourth images). Notably, they did not co-localize with VEC units, but were confined within VEC-negative junction areas (fourth image). Based on the analysis of multiple endothelial areas (n = 13) visualized in two different mouse aortas, paracellular and intracellular localizations were determined for 75% and 25% of detected HA-NPs, respectively (Figure S1C). This dominant junctional pathway of HA-NPs led to their efficient extravasation into the plaque interior, as observed 24 h after HA-NP administration (Figure S6, upper panel), and the engulfment by plaque-associated macrophages, as demonstrated in our previous study.18

Figure 3.

(A) Confocal microscopy images of VEC-stained endothelial junctions (red, first image) and HA-NPs (cyan blue, second image) at the surface of an atherosclerotic plaque. The co-distribution of HA-NP and VEC can be deduced from the overlay image (third image) and enlarged ROI depicted by the white frame (fourth image). (B) Super-resolution images of VEC organization in endothelial junctions (red, first image) and spatially resolved single HA-NPs (cyan blue, second image) on the atherosclerotic plaque surface. As shown in the overlay image (third image) and enlarged ROI indicated by the white frame (fourth image), HA-NPs are localized predominantly in the cell junction. (C) CLEM of atherosclerotic plaque section obtained 15 min after HA-NP-Cy5.5 administration. Morphological details of the plaque microenvironment were assessed by TEM (first image). The following components can be identified: vessel lumen (L), endothelial cells (EC), extracellular matrix (ECM), and macrophages/foam cells (FC). Super-resolution GSD microscopy was used for the localization of HA-NPs (second image). As deduced from the overlay image (third image), HA-NPs (red) are abundant in the ECM, at the luminal plaque side. The fourth image shows the enlarged interface area of lumen (L), endothelium (hypointense layer), and extracellular matrix (ECM). (D) In enlarged CLEM image ROIs, endothelial cells displayed no intracellular HA-NP accumulations (first image). Interestingly, within the endothelial layer, we can observe sparsely distributed rows of HA-NPs (indicated with arrow heads in second and third image), suggesting the paracellular/junctional trafficking of HA-NPs. Fourth image displays a superficially localized (close to the aortic lumen) macrophage/foam cell, which is surrounded by HA-NP-rich ECM and contains some internalized HA-NPs. The presented data were acquired in aortas of three different mice after 6-week HFD.

Correlative light (GSD) and electron microscopy (CLEM) is a powerful bimodal microscopy technique, which we used to visualize HA-NPs in the plaque microenvironment, at nanoscale spatial resolution (Figure 3C). Cryo-sections of atherosclerotic aortas were first analyzed by GSD and subsequently by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to acquire a HA-NP signal (Figure 3C, second image) and plaque morphology (Figure 3C, first image), respectively. The overlay image displays the intraplaque localization of HA-NPs 15 min after i.v. injection (Figure 3C, third image). The imaged superficial plaque area is shown at a lower magnification in the Figure S1D. HA-NPs were detected exclusively at the luminal plaque side, and they were confined predominantly to the extracellular matrix (Figure 3C, third and fourth images). The enlarged areas of CLEM image are present in the Figure 3D. The endothelial cells displayed no internalization of HA-NPs (Figure 3D, first image). However, at several sites of the endothelial layer, HA-NPs formed narrow queues (Figure 3D, second and third images), which imply the pericellular transendothelial trafficking of HA-NPs. Unfortunately, semi-thin sections of 200 nm, which we used for CLEM analysis, were too thick to precisely identify endothelial junctions (Figure S1D), but necessary for the HA-NP visualization. Interestingly, already at this early time point after HA-NP administration (15 min), we could observe some initial NP internalization in foam cells/macrophages, localized in close vicinity of the endothelium (Figure 3D, fourth image).

To investigate the contribution of atherosclerotic microvasculature in NP accumulation at lesions, confocal microscopy was used. In Figure S5B, we show an example of plaque with an extensive microvascular network. These fine vessels were found to be positive for HA-NP fluorescence, which indicates that they actively contribute to the NP distribution and extravasation (Figure S5, lower panel). However, considering the low incidence of microvasculature-positive plaques (Figure S5A, Figure S6B), we believe that the overall impact of microvasculature in NP trafficking to mouse atherosclerotic lesions is limited compared to the macrovascular endothelium.

Nanoparticle-facilitated targeting of atherosclerotic lesions has been demonstrated in several preclinical studies.46−48 However, few studies focused on the specific pathways of nanoparticle trafficking to plaques. Previously, our colleagues have investigated the mechanism of liposomal targeting of atherosclerotic lesions in New Zealand white rabbits.21 The obtained results indicated a dominant role of adventitia-originating microvasculature, which is in contrast to our mouse findings. We attribute these discrepancies to the biological context, namely, the animal model and lesion phenotype. The previously investigated rabbit lesions were highly angiogenic, with presumably absent or injured luminal endothelium, which is a consequence of balloon injury.49 In contrast, mouse atherosclerotic lesions had an “intact” luminal endothelium and rarely present microvasculature (Figure 2, Figures S5 and S6). Sluimer et al.50 demonstrated a large variability in the vascularization of human atheromas, with approximately 50 microvessels per mm2 at hotspots. 60% of those had opened endothelial junctions, as determined by TEM. On the other hand, several scanning electron microscopy (SEM) studies on human carotid artery atherosclerosis revealed a number of luminal endothelial abnormalities, including endothelial cell shape irregularities, loss of endothelial connectivity, and endothelial erosion/denudation,51,52 which is in line with our findings. Possibly, both the macrovascular endothelium and plaque microvasculature are relevant trafficking pathways for the immune cells and, potentially, for nanomedicine in human atherosclerosis.

Considering the HA-NP characteristics, that is, the diameter of approximately 90 nm, negative charge, and relatively long and biexponential blood clearance kinetics, which were studied in the previous paper,18 we believe that our findings can be extrapolated to many of the previously proposed nanoparticle platforms. Although Poller et al. demonstrated that 10 nm-large citrate-coated iron oxide nanoparticles were internalized by the endothelial cell lining of atherosclerotic lesions, the authors do not report whether this was the exclusive route.25 The virtual absence of HA-NP-endothelial cell interactions, demonstrated in Figure 3 and Figure S6, is of special interest. Hyaluronan (HA), which creates a structural backbone of HA-NPs, is a biologically active polysaccharide and a ligand of ICAM-1, an important endothelial marker involved in leukocyte adhesion.45 Molecular recognition of ICAM-1 is one of the leading concepts of endothelium-targeted drug delivery and diagnostics.53 Despite the previously reported high binding affinity of HA to ICAM-1, KD of 9 × 10–12,54 we did not observe co-localization of ICAM-1 and HA-NPs in macrophages (Figure S3B). We anticipate that HA functionalization and cross-linking may have partially affected its receptor-binding affinity compared to non-modified HA, as we have previously shown for CD44.18 In the latter case, however, a high expression of CD44, >10-fold higher compared to ICAM-1 in macrophages, sustained specific interactions with modified HA. Noteworthy, previously proposed HA-based or -functionalized NPs were also employed for CD44 targeting.55 We have also hypothesized that HA modifications are responsible for a relatively long circulation time of HA-NPs, by decreasing their recognition by the liver hyaluronan receptor for endocytosis (HARE). Considering the ICAM-1 internalization half-time between 5 and 20 min,56,57 our readout time points of 15 min and 2 h post-administration were suitable for the identification of intracellular NPs, and yet only minute endothelial cell-association was observed (Figure 3B, Figures S1C and S6C). We believe that the transcellular endothelial pathway-dependent nanostrategies are attractive, especially in advanced plaques. As demonstrated by Michaelis et al. in the blood–brain barrier, apolipoprotein E can strongly enhance endothelial transfer of nanoparticles.58 The transcellular endothelial route is also relevant for apolipoprotein A-containing high-density lipoprotein (HDL), which represents a leading concept of nanoparticle design in our group.59,60

Metabolic Modulation of Endothelial Barrier in Atherosclerosis

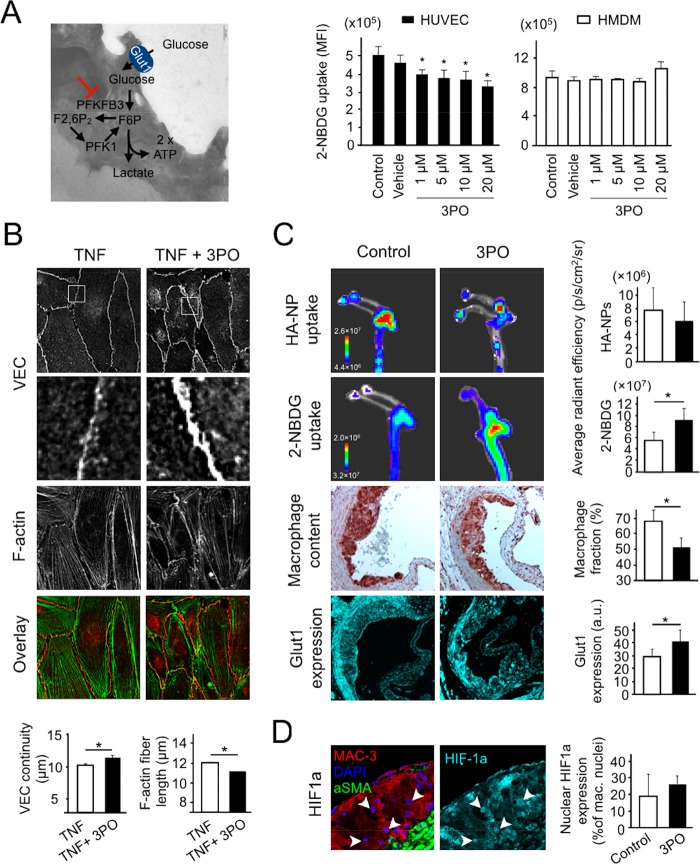

Inspired by recent findings on the tumor vascular normalization by a small-molecule glycolysis inhibitor, 3PO,19 we studied the feasibility of this therapeutic strategy in atherosclerosis. (2E)-3-(3-Pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one (3PO) exerts its antiglycolytic activity by inhibiting the 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) enzyme, which acts as a coenzyme in the glycolysis pathway (Figure 4A, left panel). Since glycolysis plays a major role in the endothelial cell and macrophage metabolism, our in vitro and in vivo experiments addressed both endothelial and inflammatory aspects of 3PO therapy. The glucose uptake and Glut1 expression were used as markers of the glycolytic activity in cells and atherosclerotic mouse aortas. The former was probed by a fluorescent glucose analogue, 2-NBDG, which mimics the clinically applied 18F-fluorodeoxygluose (18F-FDG).61 The endothelial barrier remodeling was investigated in vitro by VEC and F-actin stress fiber analysis and in vivo by using HA-NP-based permeability readout. The therapeutic outcome was validated by histology.

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic representation of the glycolysis pathway, in which 3PO inhibits activity of PFKFB3 enzyme (left panel). The right panel displays in vitro effects of different concentrations of 3PO (1–20 μM for 24 h) on the uptake of a fluorescent glucose analogue, 2-NBDG, in HUVEC and HMDM. Pure culture medium was used as a control and 0.03% DMSO as a vehicle. TNF (10 ng/mL) and LPS (100 ng/mL) were applied as pro-inflammatory co-stimuli of HUVEC and HMDM, respectively. 2-NBDG was used at a concentration of 100 μM for 30 min. (B) Representative immunofluorescence microscopy images of HUVEC treated with either 10 ng/mL of TNF (left) or 10 ng/mL of TNF and 10 μM of 3PO (TNF + 3PO, right) for 24 h. The upper panel displays VEC staining of endothelial junctions. White frames depict ROIs enlarged in the second panel. TNF treatment resulted in vague and frequently discontinued junctional VEC, which was effectively suppressed by 3PO co-incubation. Third panel from the top shows F-actin staining of cytoskeleton. The stress fiber formation was more apparent after TNF treatment compared to TNF + 3PO. The bottom panel displays an overlay image of VEC (red) and F-actin (green) images. In the charts below, the quantified VEC continuity and F-actin fiber length are compared between the TNF- and TNF + 3PO-treated HUVEC. (C) In vivo effects of glycolysis inhibition with 3PO in atherosclerotic mice. A 6-week-long therapy (3 × /week 25 mg/kg intraperitonealy) was followed by an i.v. administration of Cy5.5-labeled HA-NPs and 2-NBDG to determine the endothelial barrier integrity and glycolytic activity, respectively. Two upper panels display representative IVIS images of HA-NP and 2-NBDG signal in aortic arches form a non-treated (control, left) and 3PO-treated mouse (right). The charts in the right compare the average radiant efficacy in aortic arches between the study groups. Two lower image series represent histological data on macrophage content (third panel from the top, MAC-3-stained, brown) and glucose transporter Glut1 expression (cyan blue, bottom panel) in aortic root plaques. The corresponding charts display the quantified percentages of MAC-3-positive plaque area and mean Glut1 fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units). (D ) Representative images of atherosclerotic plaque section with nuclear expression of HIF-1α. Left image shows plaque morphology with MAC-3-stained macrophages (red), alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA)-stained smooth muscle cells (green), and DAPI-stained nuclei (blue). The right image displays the corresponding HIF-1α staining (cyan blue). Arrowheads indicate the nuclear localization of HIF-1α signal. In (A, C, D), bars represent mean ± standard deviation. In (B), the charts display mean ± standard error of the mean; control: white bars; 3PO-therapy: black bars ( n = 10). Symbol “*” represents a significant difference at p < 0.05.

First, we compared the efficacy of glycolysis inhibition by 3PO in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and human monocyte-derived macrophages (HMDM), which represent relevant cellular targets in atherosclerosis (Figure 4A, middle and right panels). The cells were treated with 3PO (1–20 μM) for 24 h. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were used as pro-inflammatory co-stimuli in HUVEC and HMDM, respectively, to mimic the inflammatory activation in atherosclerosis.62 In HUVEC, 3PO significantly and dose-dependently reduced 2-NBDG uptake, measured by flow cytometry (Figure 4A, middle panel). The cells treated with 10 μM 3PO displayed an approximately 25% lower median fluorescence intensity (MFI) compared to the control. This was associated with a significantly reduced Glut1 expression (Figure S7A, left). In contrast, the uptake of 2-NBDG in HMDM was not affected significantly by any of the tested 3PO concentrations (Figure 4A, right panel). At the same time, we found a small but significant reduction in Glut1 expression (Figure S7A, right). Similar intercellular differences in the response to 3PO were observed for HUVEC and HMDM without pro-inflammatory co-stimulation (Figure S7B).

Subsequently, we studied the effects of 3PO in an in vitro endothelial barrier model. A confluent HUVEC monolayer was treated with 10 μM 3PO and co-stimulated with TNF-α, an inflammatory cytokine, which results in the endothelial junction63,64 and cytoskeleton rearrangement.65 The lengths of VEC junctions and F-actin stress fibers were used as quantifiers of these effects. 3PO significantly inhibited TNF-α-induced endothelial activation, as demonstrated by both parameters (Figure 4B). It increased the VEC continuity, while decreasing the length of F-actin stress fibers, both by approximately 10%.

To determine the effects of 3PO in atherosclerosis, Apoe–/– mice underwent treatment in combination with a HFD. 3PO was administered intraperitoneally three times per week at the dose of 25 mg/kg, as described previously.66 After 6 weeks of treatment, the mice were injected with Cy5.5-labeled HA-NPs and 2-NBDG, 2 h and 15 min before the sacrifice, respectively. The accumulation efficacy of both probes was analyzed ex vivo by the IVIS imaging system. Figure S8 depicts a schematic overview of these therapeutic experiments. The 6-week therapeutic regimen in developing atherosclerosis was motivated by our findings on a significantly higher endothelial barrier dysfunction in early plaques compared to advanced counterparts, which undergo a natural endothelial normalization (Figure 2).

Representative IVIS images of aortic arches with HA-NP and 2-NBDG fluorescence are shown in Figure 4C (upper two panels), while the images of whole aortas can be found in Figure S9A. HA-NPs produced a patchy fluorescence signal, with hot spots at atherosclerosis-prone sites, that is, aortic arch and bifurcations, indicating selective plaque association. The quantification of HA-NP fluorescence intensity in lesion-rich aortic arches revealed an approximately 20% lower mean radiant fluorescence intensity in 3PO-treated mice compared to control counterparts. However, both groups displayed a large spread, resulting in no significant differences (Figure 4C, upper panel, and Figure S10). In contrast, 3PO treatment led to a ca. 30% higher 2-NBDG uptake compared to non-treated animals (Figure 4C, second panel from the top). Significantly enhanced mean radiance efficacy was found in both the aortic arches as well as entire aortas (Figure S9A). The aortic distribution of 2-NBDG signal was much more diffuse compared to HA-NPs, which might be due to its low-molecular weight as well as uptake by non-plaque cellular components of vessel wall.

Previously, the enhanced glucose uptake in atherosclerotic vessel wall was associated with an increased inflammatory burden and plaque progression.67 To verify this relation, we determined the macrophage content in aortic root plaques of the same animals that underwent IVIS experiments. MAC-3-positive plaque area was significantly lower in the 3PO-treated group compared to the control (Figure 4C, third panel), that is, ∼50% versus ∼70% for treated and non-treated mice, respectively. Although we found no significant differences in the plaque size, both the collagen and smooth muscle cell content, which are considered as markers of a stable plaque phenotype,68 were significantly increased in the 3PO-treated mice (Figure S9B). The necrosis fraction was low (5%) and similar in both the 3PO and control groups (Figure S9B).

The revealed mismatch between the glycolytic activity and inflammatory readout stimulated us to investigate the atherosclerotic plaque expression of the primary glucose transporter Glut1 (Figure 4C, lower panel) and hypoxia marker HIF-1α in atherosclerotic lesions (Figure 4D). The mean plaque expression of Glut1 was ∼25% higher in 3PO-treated mice compared to the control group (Figure 4C, lower, right panel). The same trend was observed when Glut1 was determined separately for the macrophage and smooth muscle cell population (Figure S9C). The analysis of nuclear translocation of HIF-1α in plaque-associated macrophages, which is explained in Figure S11, revealed on average 30% more HIF-1α-positive macrophage nuclei induced by 3PO. Notably, a large spread was observed, especially in the control group, which resulted in no significant differences.

Six-week-long antiglycolytic therapy induced no major side effects. 3PO-treated mice had a slightly lower weight gain compared the control group, as shown in Figure S12A. The major body organs displayed normal morphology (Figure S12B). In one 3PO-treated mouse, renal abnormalities were found, including immune cell infiltrations in the renal capsule and areas of necrosis. We anticipate that this might be a local effect of intraperitoneal 3PO therapy rather than its systemic manifestation. The comprehensive hematological and metabolic analyses of blood after a 3-week therapeutic regimen (three injections per week) revealed similar parameter values in both control and 3PO-treated mice (Table S1).

Glycolysis plays a key role in endothelial activation and inflammation.69 Therefore, the reprogramming of atherosclerotic plaque metabolism appears as a promising therapeutic strategy. Previously, 3PO has extensively been studied in the context of endothelial metabolic modulation. In the influential studies from the Carmeliet group, the authors demonstrated partial and transient inhibition of endothelial glycolysis by 3PO70 and its normalizing effect on tumor vasculature.19 In mouse atherosclerosis, 3PO significantly decreased glycolytic flux markers, that is, FDG-based target-to-background signal and Fru-2,6-P2, and pro-inflammatory mediators, that is, TNF-α and CCL2.71 Our study shows favorable effects of 3PO on the atherosclerotic plaque morphology, including a significantly decreased macrophage content (Figure 4C) and an increased collagen fraction (Figure S9B). However, the macroscopic readout of endothelial barrier function by HA-NPs revealed no significant response to 3PO, although the endothelial normalization trend could be observed (Figure 4C). This can potentially be attributed to a large distribution of plaque size, which we accounted in both study groups, that is, differences in the average plaque area were up to 4-fold (Figures S9 and S10). Notably, however, we found no correlation between the plaque size and HA-NP uptake in either 3PO-treated or control animals (Figure S10), which suggests a high natural variability of endothelial barrier function in atherosclerotic mice. We believe that this was a key limitation of our in vivo therapy readout, particularly, if we consider rather subtle in vitro endothelial effects of 3PO (Figure 4A,B). Alternatively to the endothelial barrier remodeling, glycolytic silencing of atherosclerotic endothelium might modulate other endothelial functions, such as the interaction with immune cells, which we do not investigate in our paper.

Our second important readout addressed the metabolic effects of 3PO therapy. Surprisingly, 3PO-treated aortas displayed a 30% higher 2-NBDG uptake compared to control vessels, although histological analysis revealed a significantly decreased macrophage burden (Figure 4C). The latter has previously been considered as a primary source of glycolytic activity in atherosclerosis and cancer.72,73 However, the mismatch between the glycolytic and inflammatory profile of an atherosclerotic vessel wall has been foreseen by Folco et al.,74 who pointed to hypoxia as an important propagator of glycolysis in both macrophages and smooth muscle cells. Accordingly, we found a significant overexpression of Glut1 in these two cell populations (Figure S9C) and a considerably increased nuclear expression of HIF-1α in macrophages (Figure 4D), which suggest a role of hypoxia in the 3PO-induced glycolytic activation. This may explain the enhanced 2-NBDG uptake, yet it seems paradoxical to the mechanism of 3PO action. Considering our in vitro findings on the 3PO selectivity toward endothelial cells (Figure 4A), the plaque endothelium might be the primary target for 3PO in atherosclerosis. It needs to be stressed that the acquired 2-NBDG signal originated predominantly from the macrophages and smooth muscle cells, the two largest cell populations in atherosclerosis plaques, while the contribution of endothelial monolayer is likely negligible. We anticipate that 3PO-induced endothelial silencing, although not readily demonstrated in our mouse experiments, may have limited the plaque accessibility to oxygen and nutrients, eventually leading to hypoxia and glycolytic activation in plaque-associated macrophages and smooth muscle cells. From a general perspective, our results shed light on the relation between the inflammation and metabolism and on the feasibility of metabolic readout for the inflammatory burden assessment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrated significant structural abnormalities in the macrovascular endothelium covering mouse atherosclerotic plaques, which correlated with the plaque targeting efficacy of HA-NPs. Interestingly, advancement of the plaque had a positive effect on the endothelial junction architecture and, consequently, a negative impact on the HA-NP plaque accumulation. By using two-color super-resolution microscopy and correlative light and electron microscopy, we traced HA-NPs in endothelial junctions and plaque microenvironment, respectively. We found that HA-NPs enter the plaque via endothelial junctions, and they subsequently distribute throughout the ECM to be eventually engulfed by plaque-associated macrophages. Finally, our therapeutic data show that a subtle normalization of endothelial barrier function, deduced from the aortic HA-NP retention, coincides with a significant modulation of inflammatory and metabolic activity in atherosclerotic lesions.

Methods

Hyaluronan Nanoparticle Preparation

Hyaluronan nanoparticles (HA-NPs) were prepared as previously described.18 In short, HA was dissolved in 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer and activated with 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA) and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (sulfo-NHS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subsequently, ethylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, United States) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The amine-functionalized HA (HA-NH2) was purified by dialysis against ultrapure water and ethanol precipitation. Afterward, the obtained product was lyophilized. NHS ester of cholanic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared by a reaction of cholanic acid with N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (Sigma-Aldrich) in dry dimethylformamide (Sigma-Aldrich). The lyophilized HA-NH2 was dissolved in 0.1 N NaHCO3 pH 9, after which the cholanic ester solution was added drop-by-drop and stirred overnight. Purification of the product was performed by filtration and dialysis against ultrapure water. The final product was freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C.

Fluorescent labeling of the nanoparticles was performed by a conjugation of cyanine5.5-NHS ester (Lumiprobe GmbH, Hannover, Germany) to the remaining primary amine groups on the HA. Cyanine5.5-NHS ester was dissolved in dry DMF and added to a solution of HA-NPs in 0.1 N NaHCO3 pH 8.5 (40% (v/v) DMF) at a 8:1 molar ratio dye to residual NH2 groups and stirred for 4 h at room temperature. Unconjugated dye was removed by ethanol precipitation and dialyses against ultrapure water.

Animal Experiments

Eight week-old Apoe–/– mice (Charles River Laboratories, Beerse, Belgium) were fed with a high-fat diet (HFD) (TD.88137, Envigo, Alconbury Huntington, UK) for either 6 or 12 weeks (n = 5/group) to induce early and advanced atherosclerotic lesions, respectively. After the diet period, the mice received an injection of Cy5.5-labeled HA-NPs (25 mg/kg) via the tail vein. Two h after injection, the mice were sacrificed and perfused with PBS. The aortic arch samples were used for both the confocal and GSD microscopy experiments. For electron microscopy and correlative light and electron microscopy, two atherosclerotic mice were perfused with McDowell Trump’s fixative (4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and 1% glutaraldehyde).

In the therapeutic study, 8 week-old Apoe–/– mice on a HFD received either no treatment (control) or three times per week intraperitoneal injection of 3PO (Sigma-Aldrich; 25 mg/kg) (metabolic therapy) (n = 10). After 6 weeks of treatment and/or diet, the mice received i.v. injection of Cy5.5-HA-NPs and 2-NBDG, a fluorescent glucose analogue (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific), 2 h and 15 min before the sacrifice, respectively. The sacrificed animals were perfused with PBS, which was followed by excision of the entire aorta, that is, aortic arch and descending aorta including the renal arterial branching. Subsequently, the aortas were imaged using the IVIS imaging system, whereas aortic roots were processed for histology.

All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

En Face Analysis of Aortic Samples by Confocal Microscopy

The aortas harvested for en face immunofluorescence microscopy experiments were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS (supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 mM MgCl2) for 12 min at room temperature (RT). Aortic arches, which are the most prone to atherosclerotic plaque development, were taken for further analysis. First, the carotid and subclavian arteries were cut out of the aortas. The aortic arch was sectioned into pieces and immobilized with 0.1 mm diameter pins on a Petri dish coated with a silicone layer, with the endothelium facing up. Subsequently, the samples were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min and blocked for 30 min with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Afterward, the vessels were incubated with goat antimouse VEC (Santa Cruz; 1:100 dilution; clone C-19) and rat antimouse CD107b (BD Pharmingen; dilution 1:100; clone M3/84) primary antibodies for 1 h at RT, then washed with 0.5% BSA in PBS, and incubated with the Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated chicken antigoat and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey antirat (both Thermo Fisher Scientific; dilution 1:100) secondary antibodies for an additional 1 h at RT. The cell nuclei were visualized using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at the concentration of 2 μg/mL for 10 min. After staining, the vessels were mounted in a drop of mowiol on microscope slides with the endothelium facing up. A glass coverslip was then placed on the top and gently pressed to flatten the tissue.

Imaging was performed by using Leica TCS SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), equipped with CS2 63×/1.40 oil objective, 405 nm UV diode and 470–670 nm Argon lasers. The localization of atherosclerotic plaques was based on intimal MAC-3-positive macrophages. In each aortic arch, we visualized approximately four lesions, for which image Z-stacks were acquired. Quantification of VE-cadherin (VEC) continuity was performed using ImageJ. First, VEC images were processed with a Gaussian Blur filter with a radius of 1.5, which was followed by the image binarization and skeletonization. Subsequently, the length of VEC skeleton branches was calculated, and the data were imported into Prism5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), with a minimum cutoff of 3 μm. The mean length of VEC branching per lesion was used for the statistical comparison of VEC continuity. To determine the efficacy of HA-NP accumulation in the plaque, first, the plaque area was defined in each Z-stack plane. Subsequently, an intensity threshold was manually set to select high-intensity Cy5.5-HA-NP-positive pixels. From the binary image, the HA-NP area was determined and normalized to the plaque area. The mean percentage of HA-NP-positive plaque area, calculated from all plaque focal planes, was used as a quantifier of the plaque accessibility to HA-NPs.

En Face Analysis of Aortic Samples by Super-Resolution Fluorescence Microscopy

Samples used for super-resolution fluorescence microscopy underwent the same fixation protocol as the samples used for confocal microscopy imaging (4% PFA; 12 min). The samples were stained using rat antimouse VEC (Biolegend, San Diego, USA; dilution 1:100; clone BV13) primary antibody, for 1 h, in combination with a goat antirat Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fischer Scientific; dilution 1:100) for an additional 1 h. The aortic sample was placed on an ultraclean coverslip and covered with a drop of imaging buffer (50 μL mercaptoethylamine (MEA; Sigma-Aldrich) 0.5 M, pH 8–8.5; 3 μL of NaOH 5M; 15 μL of oxygen-reducing reagent OxeA (Oxyrase Inc., Mansfield, USA); 100 μL of sodium d,l-lactate (equal concentration of d and l isomers and 350 μL PBS) before being covered with a second coverslip to stabilize its position. The sample was then mounted on a Chamlide CMB magnetic chamber (Live Cell Instrument, Chamlide CM-B25-1).

Ground-state depletion (GSD) followed by individual molecule return (GSDIM) imaging was performed in total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) mode with a Leica SR-GSD microscope (Leica Microsystems; Wetzlar, Germany), equipped with a 160×/oil immersion dedicated SR objective, a sCMOS pco.edge42 camera, and a 647 nm/500 mW laser. Between 20,000 and 40,000 frames were acquired with a 10 ms exposure time with image size of 180 × 180. Raw data sets were processed using the ImageJ plug-in ThunderStorm,75 and images were reconstructed with a rendering pixel size of 20 nm.

The processed GSDIM images were analyzed with respect to the continuity of VEC expression, which was manually determined as the largest distance between VEC molecules by using ImageJ. This was done for both the normal vessel wall and atherosclerotic endothelial data (n = 13). The subcellular localization of HA-NPs in the atherosclerotic endothelium was analyzed for the para- (junction) and intracellular compartments. First, the total number of HA-NPs was determined from the binary image, applying a size threshold of four pixels. Subsequently, the endothelial junction area was delineated based on the VEC molecule expression, and the number of associated HA-NPs was determined (Figure S1C). HA-NPs outside the junction were considered as intracellular. For statistical comparison, normalized HA-NP values were used.

Transmission Electron Microscopy and Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy of Aortic Sections

Aortic arches were fixed using McDowell Trump’s fixative for 24 h. Subsequently, they were infiltrated in a series of gelatin (until 12%) in PBS, incubated overnight in 2 M sucrose, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Semi-thin cryo-sections (100–250 nm) were cut as described by Bedussi et al.76 and transferred to a copper finder or normal 150 mesh grid.

For transmission electron microscopy, the samples were stained with a mixture of uranyl acetate/tylose and imaged using a Tecnai T12 electron microscope at 120 kV. For correlative fluorescence and electron microscopy, the aortic sections were first imaged with GSDIM microscope to detect Cy5.5-labeled HA-NPs. The sample preparation and image acquisition was the same as described in the section on super-resolution microscopy. Additionally, epifluorescence images were acquired for the morphological context. Subsequently, the sample grids were carefully washed with water, stained with a uranyl acetate/tylose mixture and imaged using a Tecnai T12 electron microscope. The image alignment was based on morphological hallmarks visible by both fluorescence and electron microcopy, that is, elastin and macrophage lipid droplets, and was performed in Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe inc., San Jose, USA).

In Vitro Effects of 3PO on the Endothelial Barrier Integrity

HUVEC (passage 3) were seeded on fibronectin-coated glass coverslips and grown for 24 h until confluency. The cells were stimulated with either TNF-α (10 ng/mL) alone or in combination with 10 μM 3PO (Axon Medchem). DMSO was used as vehicle control. After 24 h, the cells were fixed for 10 min at RT with 4% PFA in PBS++.

Fixed HUVEC were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min and blocked for 15 min with 2% BSA in PBS. After blocking, the cells were incubated for 45 min at RT with VEC primary polyclonal rabbit antibody (Cayman Chemical; dilution 1:100), washed with 0.5% BSA in PBS, and incubated at RT with a secondary chicken antirabbit Alexa Fluor 594 coupled antibody (Invitrogen; dilution 1:100) in combination with Promofluor 488-coupled phalloidin (F-actin staining; PromoKine; dilution 1:200) for an additional 45 min. DAPI (2 μg/mL) was used to visualize the cell nuclei. Coverslips were then mounted with mowiol on microscope slides. Widefield imaging was performed on Nikon microscope, equipped with Apo TIRF 40× oil objective, 470–670 argon laser, and an Andor Zyla sCMOS digital camera. All obtained images were adjusted for brightness/contrast and processed with an unsharp mask filter in ImageJ (National Institute of Health). Image processing and quantification of VEC continuity were performed using the same method as described in the en face analysis of aortic samples by confocal microscopy. F-actin continuity was quantified using the same protocol as for VEC, using a minimum branch length cutoff of 7 μm.

In Vitro Evaluation of Metabolic Effects of 3PO in Human Endothelial Cells and Macrophages

To determine the cell type specific metabolic effects of 3PO, the uptake of fluorescent glucose analogue 2-NBDG and expression of GLUT-1 receptor was measured by flow cytometry (FACS). HUVEC and HMDM were incubated with 3PO at a concentration ranging from 1 μM to 30 μM. Non-treated or DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) treated cells were used as controls. After 30 min of pretreatment, 100 ng/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and 10 ng/mL of TNF-α were added to HMDM and HUVEC, respectively. After 24 h, the medium was replaced by fresh medium containing 100 μM of 2-NBDG. After 30 min of incubation, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. The HUVEC and HMDM were detached by 5 min incubation with trypsin or citrate solution, respectively. The cell suspension was transferred to U-bottom 96-wells plates (Greiner), centrifuged for 5 min at 600 g, and resuspended in FACS buffer (2 mM EDTA, 0.5% BSA in PBS). Cells that were incubated with either DMSO or 10 μM 3PO were resuspended in FACS buffer containing rabbit polyclonal antimouse GLUT-1 antibody (Merck; dilution 1:100) and incubated for 30 min. For HMDM, i.v. immunoglobulin (IVIG; Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; dilution 1:100) was used to block fc-receptor binding. After washing with FACS buffer, antirabbit Alexa Fluor 647 secondary antibody (dilution 1:500) was added, and the cell suspension was incubated for another 30 min. Afterward, the cells were washed two times and resuspended in 100 μL of FACS buffer.

FACS measurements were performed on a CytoFLEX S flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Data analysis was carried out using FlowJo V10 software (FLOWJO, Ashland, OR, USA). A single cell population was selected on the basis of forward and side scatter. Within this population, the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 2-NGBG signal was determined as a parameter of glucose uptake, while MFI of Alexa Fluor 647 was used as a measure of GLUT-1 expression.

IVIS Imaging of Aortas

IVIS imaging was performed on a IVIS 200 Spectrum optical imaging system (Xenogen, Corporation, Alameda, USA) at the imaging unit of the Mouse Cancer Clinic at The Netherlands Cancer Institute. The vessels were immobilized on clear plastic dishes with lids (dimensions 41 × 23 × 12 mm), coated with BISON silicone (color antracid). The dishes were filled with PBS to prevent dehydration, sealed, and stored in dark at 4 °C until imaging. The fluorescence signal of 2-NBDG was imaged using an excitation filter of 465 nm and emission filter of 540 nm. For imaging of Cy5.5-HA-NP fluorescence, an excitation filter of 675 nm and emission filter of 720 nm were used. For both 2-NBDG and Cy5.5-HA-NP imaging, the exposure time was 1 s. Image analysis was performed using Living Image 4.0 software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, USA). For each sample, a ROI was drawn around the aortic arch and the first part of subclavian and carotid branches. For each ROI, the average radiant efficiency of 2-NBDG and Cy5.5-HA-NP was quantified and used for statistical comparison.

Histology of Aortic Roots

To determine the effects of metabolic therapy on the atherosclerotic plaque size and morphology, the hearts with aortic roots were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, followed by dehydration and embedding in paraffin. Subsequently, the roots where cut into 4 μM-thick sections. Before staining, the sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated.

The plaque size and necrosis fraction was determined from the hematoxyline and eosin (H&E; Sigma-Aldrich)-stained aortic root sections. The mean plaque area was derived from measurements of 5–6 sections per mouse, in which all three aortic valves were present. The plaque necrosis was measured as the acellular plaque area and normalized to the total plaque area. Collagen content was quantified based on Sirius red (Sigma-Aldrich) staining.

For immunohistochemical stainings, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by treatment with 0.3% H2O2 (Merck, Burlington, USA) in methanol for 30 min. Subsequently, the samples were placed in boiling citrate-based antigen unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, USA) for 10 min. Blocking was performed for 60 min using 4% FCS in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 1% BSA and 0.1% Tween-20. The macrophage and smooth muscle cell content was determined in sections stained with rat antimouse MAC-3 (BD Pharmingen; dilution 1:30; clone M3/84) and mouse antimouse α smooth muscle actin (αSMA; Sigma-Aldrich; 1:500; clone 1A4) primary antibody, respectively. After overnight incubation with the primary antibodies, biotinylated rabbit antirat (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA; dilution 1:300) or biotinylated goat antimouse (DAKO; dilution 1:1250) secondary antibody was applied for 30 min. Thereafter, avidin-peroxidase (Vectastatin Elite ABC HRP Kit, Vector Laboratories) was added for another 30 min. Color development was induced using ImmPact AMEC red peroxidase substrate (Vector Laboratories). Images were acquired using a light microscope (Leica Microsystems) at 100× magnification.

The expression of HIF-1α and Glut1 in aortic root plaques was determined by immunofluorescence. HIF-1α and Glut1 were stained with a rabbit antimouse HIF-1α (Novus, Littleton, USA; dilution 1:50) and rabbit antimouse Glut1 (Merck; dilution 1:200) polyclonal primary antibody, respectively. As a secondary antibody, a donkey antirabbit Alexa 647 conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fischer Scientific; 1:500 dilution) was applied. Macrophages were visualized using a rat antimouse MAC-3 primary antibody (BD Pharmingen; dilution 1:100; clone M3/84) in combination with a donkey antirat Alexa 594-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fischer Scientific; 1:500 dilution). Smooth muscle cells were stained with a FITC-conjugated antimouse αSMA primary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; 1:3000; clone 1A4). The sections were incubated with the aforementioned primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, after which the samples were washed, and secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI at a concentration of 2 μg/mL for 10 min. Images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Quantification of collagen, MAC-3, and αSMA area was performed using ImageJ. First, RGB images were converted to 8-bit gray-scale images. After adjusting an intensity threshold, the stained area was masked, quantified, and normalized to the total plaque area. Quantification of the Glut1 and HIF-1α expression was performed using LAS X software (Leica Microsystems). For Glut1, first the atherosclerotic plaques were defined as ROIs on the basis MAC-3 and αSMA staining. Subsequently, the average fluorescence intensity of Alexa 647-stained Glut1 was calculated from all ROIs. Glut1 expression was also determined separately for MAC-3 and αSMA-positive plaque areas. Nuclear expression of HIF-1α was determined for plaque-associated macrophages. Only macrophages with a well-defined cytoplasm and nucleus were included in the analysis (∼50 cells/plaque). For each included macrophage, a line was drawn through the cytoplasm and nucleus to generate the signal intensity histogram of Alexa Fluor 647-HIF-1α. DAPI histogram served as a reference (representative histograms can be found in Figure S11). The nucleus was considered as HIF-1α positive if its HIF-1α fluorescence signal was approximately 3-fold higher compared to the cytoplasm. The percentage of HIF-1α positive macrophage nuclei was used as a quantifier of hypoxic activation.

Statistical Analysis

The normality of data distribution was tested with a Shapiro-Wilk test. The comparison of the endothelial junction continuity in the plaque and normal vessel wall was performed using a two-tailed paired Student’s t test. The intergroup comparisons of the endothelial junction continuity and HA-NP plaque accumulation were done using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. The same analysis was performed when comparing the largest intrajunctional distance and endothelial cell thickness between the plaque and normal vessel wall. In vitro data on glucose uptake in HUVEC and HMDM were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. The in vitro VEC continuity and F-actin fiber length data were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t test. The same test was used to compare the histological outcome of the 3PO and control group. All of the analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 by setting the significance level at p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL118440 (W.J.M.M.), R01 HL125703 (W.J.M.M.), R01 CA155432 (W.J.M.M.), as well as The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) Vidi (016.136.324, W.J.M.M.), Vidi (016.156.327, S.H.), STW (15851, W.J.M.M.), and Vici (016.176.622, W.J.M.M.). The authors also thank Sensi Pharma BV for their funding. We thank Ralph J. Sinn and Pascal J. H. Kusters for help with histopathological preparation and analysis.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.8b08875.

Figures S1–S12 and Table S1 (PDF)

Author Contributions

○ These authors contributed equally to the study. T.J.B., T.M., E.D., S.vdV., C.P.A.A.vR., L.B., and E.K. preformed in vivo and/or ex vivo animal experiments. E.K., S.H., W.J.M.M., and E.L. designed the experiments and supervised them. A.L.S.M. contributed to the in vitro cell experiments. A.E.G. preformed TEM experiments. E.D. and E.K. performed GSD experiments. N.N.vd.W. and H.A.vV. supervised electron and super-resolution microscopy. M.P.J.d.W, A.E.N., J.C.S., R.A.H., and P.A.K. were valuable advisors. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Duivenvoorden R.; Tang J.; Cormode D. P.; Mieszawska A. J.; Izquierdo-Garcia D.; Ozcan C.; Otten M. J.; Zaidi N.; Lobatto M. E.; van Rijs S. M.; Priem B.; Kuan E. L.; Martel C.; Hewing B.; Sager H.; Nahrendorf M.; Randolph G. J.; Stroes E. S. G.; Fuster V.; Fisher E. A.; et al. A Statin-Loaded Reconstituted High-Density Lipoprotein Nanoparticle Inhibits Atherosclerotic Plaque Inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3065. 10.1038/ncomms4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobatto M. E.; Fayad Z. A.; Silvera S.; Vucic E.; Calcagno C.; Mani V.; Dickson S. D.; Nicolay K.; Banciu M.; Schiffelers R. M.; Metselaar J. M.; van Bloois L.; Wu H.-S.; Fallon J. T.; Rudd J. H.; Fuster V.; Fisher E. A.; Storm G.; Mulder W. J. M. Multimodal Clinical Imaging To Longitudinally Assess a Nanomedical Anti-Inflammatory Treatment in Experimental Atherosclerosis. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2010, 7, 2020–2029. 10.1021/mp100309y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Kantoff P. W.; Wooster R.; Farokhzad O. C. Cancer Nanomedicine: Progress, Challenges and Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 20–37. 10.1038/nrc.2016.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharagozloo M.; Majewski S.; Foldvari M. Therapeutic Applications of Nanomedicine in Autoimmune Diseases: From Immunosuppression to Tolerance Induction. Nanomedicine (N. Y., NY, U. S.) 2015, 11, 1003–1018. 10.1016/j.nano.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder W. J. M.; Jaffer F. A.; Fayad Z. A.; Nahrendorf M. Imaging and Nanomedicine in Inflammatory Atherosclerosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 239sr1. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y.; Maeda H. A New Concept for Macromolecular Therapeutics in Cancer Chemotherapy: Mechanism of Tumoritropic Accumulation of Proteins and the Antitumor Agent Smancs. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington K. J.; Mohammadtaghi S.; Uster P. S.; Glass D.; Peters A. M.; Vile R. G.; Stewart J. S. Effective Targeting of Solid Tumors in Patients with Locally Advanced Cancers by Radiolabeled Pegylated Liposomes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 243–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukourakis M. I.; Koukouraki S.; Giatromanolaki A.; Kakolyris S.; Georgoulias V.; Velidaki A.; Archimandritis S.; Karkavitsas N. N. High Intratumoral Accumulation of Stealth Liposomal Doxorubicin in Sarcomas: Rationale for Combination with Radiotherapy. Acta Oncol 2000, 39, 207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhier F. To Exploit the Tumor Microenvironment: Since the EPR Effect Fails in the Clinic, What Is the Future of Nanomedicine?. J. Controlled Release 2016, 244, 108–121. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar U.; Maeda H.; Jain R. K.; Sevick-Muraca E. M.; Zamboni W.; Farokhzad O. C.; Barry S. T.; Gabizon A.; Grodzinski P.; Blakey D. C. Challenges and Key Considerations of the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect for Nanomedicine Drug Delivery in Oncology. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2412–2417. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.; Shields A. F.; Siegel B. A.; Miller K. D.; Krop I.; Ma C. X.; LoRusso P. M.; Munster P. N.; Campbell K.; Gaddy D. F.; Leonard S. C.; Geretti E.; Blocker S. J.; Kirpotin D. B.; Moyo V.; Wickham T. J.; Hendriks B. S. 64 Cu-MM-302 Positron Emission Tomography Quantifies Variability of Enhanced Permeability and Retention of Nanoparticles in Relation to Treatment Response in Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4190–4202. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]