Abstract

Background

Recent studies have suggested that anticoagulant therapy does not confer a survival benefit overall in sepsis, but might be beneficial in sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). In particular, those with high Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores might be the optimal target for anticoagulant therapy. However, both DIC and SOFA scores require the measurement of multiple markers. The purpose of this study was to explore a minimal marker set for determining coagulopathy at high risk of death in septic patients, wherein histone H3 levels were evaluated as indicators of both organ failure and coagulation activation.

Methods

We analyzed correlations among levels of serum histone H3 and other coagulation markers in 85 cases of sepsis using Spearman’s rank correlation test. We then compared the utility of histone H3 to that of other coagulation markers in predicting the traditional DIC state or 28-day mortality by receiver-operating characteristics analysis. Finally, we suggested cut-off values for determining coagulopathy with high risk of death, and evaluated their prognostic utility.

Results

Serum histone H3 levels significantly correlated with thrombin-antithrombin complex (TAT) levels (Spearman’s ρ = 0.46, p < 0.001), and weakly correlated with platelet counts (Spearman’s ρ = − 0.26, p < 0.05). Compared to other coagulation markers, histone H3 levels showed better performance in predicting 28-day mortality. When combining serum histone H3 levels with platelet counts, our new scoring system showed a concordance rate of 69% with the traditional four-factor criteria of DIC established by the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine. The 28-day mortality rates of the new and the traditional criteria-positive patients were 43% and 21%, respectively. Those of the new and the traditional criteria-negative patients were 5.7% and 9.4%, respectively.

Conclusions

Serum histone H3 levels and platelet counts are potential markers for determining coagulopathy with high risk of death in septic patients. Further studies are needed to clarify the utility of serum histone H3 levels in the diagnostic of coagulopathy/DIC.

Keywords: Sepsis, Disseminated Intravascular coagulation (DIC), Diagnosis, Histone

Background

Sepsis is a life-threatening disorder resulting from dysregulated host responses to infection [1]. Although the details of dysregulated host responses are not defined, insufficiency of microcirculation associated with excessive activation of the complement system, the coagulation system, and the innate immune system might be involved [2]. These exaggerated proinflammatory and procoagulant responses have been the predominant target of clinical intervention; however, none has proven effective to date [3]. Considering that sepsis is a particularly heterogeneous syndrome, the selection of patients who may benefit from a certain intervention is required [2].

Recent studies have suggested that anticoagulation therapy does not confer a survival benefit overall in sepsis, but might be beneficial in the specific subpopulation with sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [4–6], with those with high disease severity as the optimal target for anticoagulation [7]. Several organizations have proposed diagnostic criteria for DIC, including the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) [8], the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) [9], and the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (JSTH) [10]. However, DIC is not routinely diagnosed in most institutions in part because diagnostic criteria require the measurement of multiple coagulation markers, such as prothrombin time (PT), fibrin(ogen) degradation products (FDP), and thrombin-antithrombin complex (TAT), some of which are not commonly available.

Histone H3 is one of the nucleosome core proteins, acting as a spool around which DNA winds. In septic conditions, histone H3 and other histones can be released from activated neutrophils and severely injured cells into the extracellular space, where they induce platelet aggregation [11, 12], coagulation activation [13], endothelial damage [14, 15], and cardiac injury [16]. Recently, we developed an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) which can measure serum or plasma histone H3 levels with high sensitivity and specificity [17]. Using this ELISA, we found that circulating histone H3 levels in septic patients were associated with coagulopathy, multiple organ failure, and death [18]. These findings led us to speculate that serum histone H3 levels might be a simple biomarker for selecting coagulopathy patients at high risk of death who may benefit from anticoagulation therapy [5, 7]. In this study, we explore a minimal marker set for determining coagulopathy at high risk of death in septic patients, wherein histone H3 levels were evaluated as indicators of both organ failure and coagulation activation.

Methods

Study population

This investigation was performed using a data set from a single-center observational study conducted in Kagoshima University Hospital between July 2015 and June 2016 [18]. Among 85 cases of sepsis enrolled in this study, serum samples were obtained in 81 patients within 24 hours after intensive care unit admission (ICU day 1) and analyzed for histone H3 levels. Diagnosis of DIC was made according to the JAAM DIC criteria on day 1, 3, 5, and 7. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) scores and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores were calculated with reference to the medical records although the APACHE II scores and the SOFA scores in this study did not include the Glasgow Coma Scale scores due to invalid assessment of the scores under sedation. The study was compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kagoshima University.

Measurement of histone H3 and coagulation markers

Serum histone H3 levels were measured by ELISA using antibodies against histone H3 (Shino-Test Corporation, Sagamihara, Japan) as described previously [17, 18]. The lower detection limit of the ELISA was 2 ng/mL, and the linearity was observed in the range up to 250 ng/mL. The ELISA specifically detected histone H3 and did not react with other histones, including histone H2A, H2B, and H4 [17, 18].

Plasma FDP and TAT levels were determined by LPIA FDP (LSI Medience, Tokyo, Japan) and STACIA CLEIA TAT (LSI Medience, Tokyo, Japan), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma PT and antithrombin (AT) activity were analyzed using HemosIL RecombiPlasTin (Instrumentation Laboratory Company, Bedford, MA, USA) and HemosIL Liquid Antithrombin (Instrumentation Laboratory Company), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Platelet counts were analyzed using an automated counting device XE-5000 (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using commercial software (SPSS version 23 IBM, Inc., Armonk NY, USA). The relationship between serum histone H3 levels and other coagulation markers was analyzed by Spearman’s rank correlation test. The predictive ability of each parameter for the traditional DIC state established by JAAM or 28-day mortality was compared by receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) analysis. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

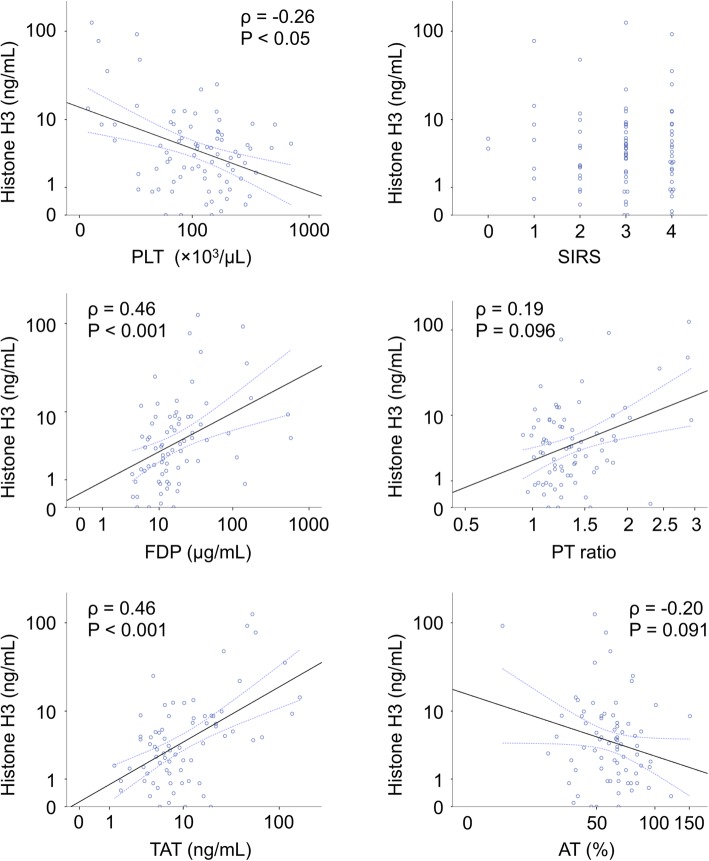

First, we assessed the characteristics of histone H3 levels in the setting of sepsis-associated DIC by analyzing its correlation with other coagulation markers. The basic characteristics of the study population were shown previously [18]. As shown in Fig. 1, serum histone H3 levels were significantly correlated with TAT levels (Spearman’s ρ = 0.46, p < 0.001) and FDP levels (Spearman’s ρ = 0.46, p < 0.001), and weakly correlated with platelet counts (Spearman’s ρ = − 0.26, p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Serum histone H3 levels are correlated with coagulation markers. Correlations between serum histone H3 levels (ng/mL) and coagulation marker levels, including platelet counts (PLT, × 103/μL), fibrin(ogen) degradation products levels (FDP, μg/mL), thrombin-antithrombin complex levels (TAT, ng/mL), SIRS score, prothrombin time (PT) ratio, and antithrombin activity (AT, %), on ICU day 1 are shown. Spearman’s ρ and p values, are also shown. Logarithmic scales are used, except for SIRS score.

We then compared the diagnostic utility of histone H3 to that of other coagulation markers for predicting the traditional DIC state or 28-day mortality. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) of serum histone H3 levels for predicting the traditional DIC state was 0.75, approximately equivalent to the value of constituent makers for DIC, such as platelets (0.79), PT (0.60), FDP (0.76), and TAT (0.70), and better than that of high mobility group box 1, the prototypical damage-associated molecular pattern molecule. The AUC of serum histone H3 levels for predicting 28-day mortality was 0.73, better than that of other coagulation markers, such as platelets (0.72), PT (0.68), FDP (0.57), and TAT (0.58).

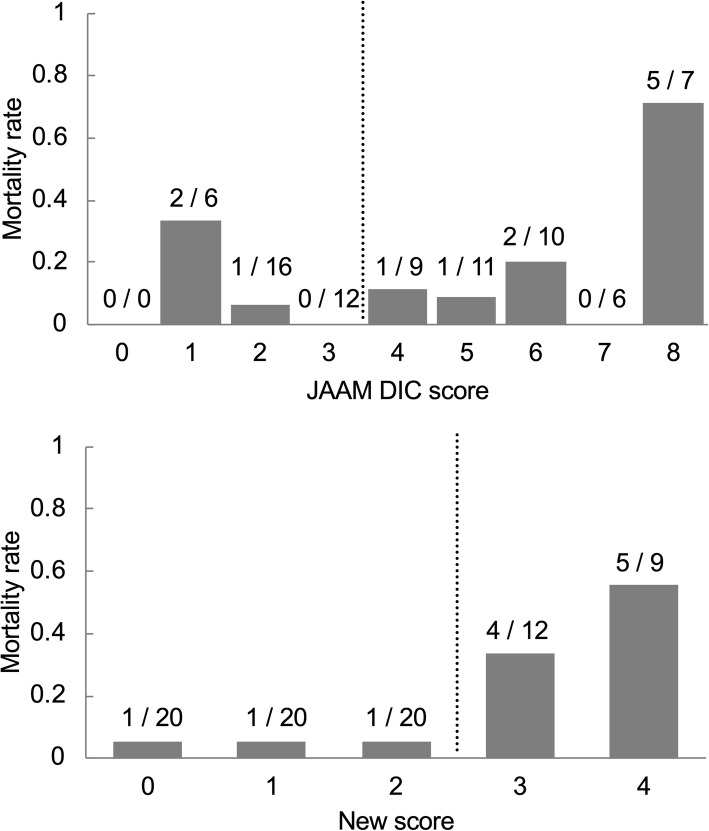

Subsequently, we assessed whether serum histone H3 levels could be a good substitute for FDP, PT, and the disease severity markers for selecting coagulopathy patients at high risk of death. To this end, we proposed a new scoring system, consisting of platelet counts and serum histone H3 levels (Table 1). The cut-off values of serum histone H3 levels and platelet counts were determined by ROC analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S1). A sum score ≥ 3 was considered to be coagulopathy with high risk of death in the new scoring system. As shown in Table 2, the diagnostic concordance rate was 69% (51/74) between the traditional JAAM criteria and the new two-factor scoring system. The 28-day mortality rates of the new and traditional criteria-positive patients were 43% and 21%, respectively. The 28-day mortality rates of the new and traditional criteria-negative patients were 5.7% and 9.4%, respectively. Consistent with these findings, the new scoring system could clearly discriminate patients at high risk of death from those at low risk (Fig. 2). The AUC of the new scoring system for predicting 28-day mortality was 0.80, better than that of other prognostic scores in the ICU setting, such as the SOFA score (0.78) and the APACHE II score (0.71). Thus, the new scoring system could determine coagulopathy at high risk of death in septic patients in a simple manner.

Table 1.

The new scoring system for identifying coagulopathy patients at high risk of death. The scoring system using serum histone H3 level and platelet counts is shown. A sum score of ≥ 3 is considered to be coagulopathy with high risk of death

| Histone H3 (ng/mL) | |

| < 3 | 0 |

| 3 ≤ < 9 | 1 |

| 9 ≤ | 2 |

| Platelet (× 103/μL) | |

| > 120 | 0 |

| 80 ≤ < 120 | 1 |

| ≤ 80 | 2 |

| Sum score | |

| 3 ≤ | Coagulopathy with high risk of death |

Table 2.

Diagnostic concordance rates between the JAAM DIC criteria and new scoring system. The diagnostic concordance rate between the JAAM DIC criteria and the new scoring system on ICU day 1 is 69%. This can be calculated by dividing the numbers of double-negative patients and double-positive patients (31 + 20) by the total number of patients (74). The mortality rates of the new and the JAAM DIC criteria-positive patients were 43% (9/21) and 21% (9/42), respectively. The mortality rates of the new and the JAAM DIC criteria-negative patients were 5.7% (3/53) and 9.4% (3/32), respectively

| Number of patients | JAAM DIC score | |||

| < 4 (negative) | 4 ≤ (positive) | Total | ||

| New score | < 3 (negative) | 31 | 22 | 53 |

| 3 ≤ (positive) | 1 | 20 | 21 | |

| total | 32 | 42 | 74 | |

| Mortality rate | JAAM DIC score | |||

| < 4 (negative) | 4 ≤ (positive) | Total | ||

| New score | < 3 (negative) | 6.5% (2/31) | 4.5% (1/22) | 5.7% (3/53) |

| 3 ≤ (positive) | 100% (1/1) | 40% (8/20) | 43% (9/21) | |

| Total | 9.4% (3/32) | 21% (9/42) | 16% (12/74) | |

Fig. 2.

The new scoring system clearly detect patients at high risk of death. Mortality rates of patients with each JAAM DIC score and the new score on ICU day 1 are shown. Dotted lines represent cut-off lines for JAAM DIC criteria and the new scoring system. The numerator and denominator of a fraction represent the number of non-survivors divided by the sum of the survivors + non-survivors in each score.

Discussion

In this study, we propose a simple scoring system for determining coagulopathy at high risk of death in septic patients. The new scoring system is designed to be (i) simple, (ii) concordant with traditional DIC diagnosis, and (iii) prognostically relevant. A set of two parameters, platelet counts and serum histone H3 levels, showed excellent performance for this purpose.

Recent studies have suggested that the optimal target for anticoagulation therapy in septic conditions might be DIC patients with high disease severity [5, 7]. The JAAM DIC criteria are widely used in Japan and are recommended for the diagnosis of sepsis-associated DIC [19]. They consist of four parameters, namely, platelet count, FDP, PT, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) [9]. Allowing that no single biomarker has yet been reported by which DIC can be specifically diagnosed, combinational evaluation of four parameters might become a bottleneck in the diagnosis process. In the setting of sepsis, a decrease in platelet count is associated with impairment of vascular integrity [20]. An elevation of FDP is associated with activation of the coagulation and fibrinolysis pathways [21]. A prolongation of PT is generally associated with liver dysfunction, including shock liver, in the setting of sepsis [22]. SIRS is associated with an increased risk of coagulopathy and organ dysfunction [23]. Overall disease severity can be assessed by the SOFA score [5, 7, 24]. Circulating histone H3 levels are associated with multiple organ failure and coagulopathy [18] and significantly correlated with FDP levels (Fig. 1). Thus, circulating histone H3 levels can be a good substitute for FDP, PT, SIRS, and the disease severity marker. Indeed, when combining circulating histone H3 levels with platelet counts, our simple two-factor scoring system could identify 70% of patients with DIC and high disease severity and 83% of those without (Additional file 1: Table S1). Furthermore, with respect to the remaining 20% unmatched cohort, our two-factor scoring system showed good prognostic performance. These findings indicate that the new scoring system could identify coagulopathy patients with high disease severity in a simple manner.

The present study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective observational study, and the cut-off values of our new scoring system were set to optimize diagnostic performance. Thus, the utility of the new scoring system could not be validated in this study and should be validated in future studies. Second, most of the JAAM DIC-positive and new scoring system-negative patients survived 28 days, but it is not clear whether anticoagulant therapy was dispensable in these patients. Anticoagulant therapy was conducted in 52% of enrolled patients based on the JAAM DIC scores and clinical features, and might have contributed to the survival of the JAAM DIC-positive and new scoring system-negative patients. Prospective intervention studies are needed for rigorous comparison of JAAM DIC criteria and our new scoring system. Third, DIC scores other than the JAAM DIC score, such as the ISTH DIC score, were not available in this study because of the retrospective nature. Fourth, applicability of the new scoring system to patients with hematologic disorders is not clear because thrombocytopenia can be observed in these patients independently of DIC and circulating histone H3 levels may not be elevated in leukopenic patients [17]. Fifth, histone H3 levels can be measured at present for research purposes only and cannot be measured in clinical settings. This is closely related to the novelty of this study, but is simultaneously related to the disadvantage. Further studies are required for the clinical application of histone H3 measurement. Finally, it is not clear in this study whether the elevation of histone H3 levels is a cause or consequence of DIC, although some studies have demonstrated that extracellular histones activate platelets and coagulation pathways [11–13, 25]. This may be important when considering a therapeutic strategy for DIC.

Conclusions

Serum histone H3 levels correlated with FDP and TAT levels in septic patients. When combining serum histone H3 levels with platelet counts, the new scoring system indicated coagulopathy with high risk of death in a simple manner. Further studies are needed to clarify the utility of serum histone H3 levels in the diagnosis of coagulopathy/DIC.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. ROC analyses of platelet counts and serum histone H3 levels for predicting 28-day mortality. Table S1. The new scoring system identified coagulopathy patients with high disease severity.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Chinatsu Kamikokuryo, Miho Yamada, Ryo Sugimoto, and all members of the clinical laboratory in Kagoshima University Hospital for their excellent technical assistance. The authors also thank Libby Cone, MD, MA, from DMC Corp. (www.dmed.co.jp <http://www.dmed.co.jp/>) for editing drafts of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- APACHE II

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- AT

Antithrombin

- AUC

Area under the ROC curve

- DIC

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FDP

Fibrin(ogen) degradation products

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- ISTH

International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis

- JAAM

Japanese Association for Acute Medicine

- JSTH

Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis

- PT

Prothrombin time

- ROC

Receiver-operating characteristics

- SIRS

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- TAT

Thrombin-antithrombin complex

Authors’ contributions

TI designed the experimental protocol and wrote the manuscript. TI, TT, YY, TY, and HF analyzed clinical data. SY participated in the laboratory experiments. IM and YK critically appraised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This single-center observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kagoshima University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The ELISA for histone H3 is a product in the development of Shino-Test Corporation, where SY is an employee. IM holds an endowed chair at Kagoshima University and receives research funding from Shino-Test Corporation. The funding is for academic promotion and is not directly related to the present study. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Takashi Ito and Takaaki Totoki contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Takashi Ito, Email: takashi@m3.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Takaaki Totoki, Email: ttktkak@gmail.com.

Yayoi Yokoyama, Email: yokoyama@m.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Tomotsugu Yasuda, Email: yasutomo@m.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Hiroaki Furubeppu, Email: m00082hf@jichi.ac.jp.

Shingo Yamada, Email: shingo.yamada@shino-test.co.jp.

Ikuro Maruyama, Email: maruyama@m2.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Yasuyuki Kakihana, Email: kakihana@m3.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s40560-019-0420-2.

References

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Poll T, van de Veerdonk FL, Scicluna BP, Netea MG. The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(7):407–420. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL, Opal SM, Reinhart K, Turnbull IR, Vincent JL. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16045. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umemura Y, Yamakawa K, Ogura H, Yuhara H, Fujimi S. Efficacy and safety of anticoagulant therapy in three specific populations with sepsis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(3):518–530. doi: 10.1111/jth.13230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamakawa K, Umemura Y, Hayakawa M, Kudo D, Sanui M, Takahashi H, et al. Japan Septic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation study group: benefit profile of anticoagulant therapy in sepsis: a nationwide multicentre registry in Japan. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1415-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kienast J, Juers M, Wiedermann CJ, Hoffmann JN, Ostermann H, Strauss R, et al. Treatment effects of high-dose antithrombin without concomitant heparin in patients with severe sepsis with or without disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(1):90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umemura Y, Yamakawa K. Optimal patient selection for anticoagulant therapy in sepsis: an evidence-based proposal from Japan. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(3):462–464. doi: 10.1111/jth.13946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor FB, Jr, Toh CH, Hoots WK, Wada H, Levi M. Scientific Subcommittee on Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH): Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(5):1327–1330. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1616068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gando S, Iba T, Eguchi Y, Ohtomo Y, Okamoto K, Koseki K, et al. A multicenter, prospective validation of disseminated intravascular coagulation diagnostic criteria for critically ill patients: comparing current criteria. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):625–631. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000202209.42491.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wada H, Takahashi H, Uchiyama T, Eguchi Y, Okamoto K, Kawasugi K, et al. The approval of revised diagnostic criteria for DIC from the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Thromb J. 2017;15:17. doi: 10.1186/s12959-017-0142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs TA, Bhandari AA, Wagner DD. Histones induce rapid and profound thrombocytopenia in mice. Blood. 2011;118(13):3708–3714. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakahara M, Ito T, Kawahara K, Yamamoto M, Nagasato T, Shrestha B, et al. Recombinant thrombomodulin protects mice against histone-induced lethal thromboembolism. PloS One. 2013;8(9):e75961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, Dale GL, Friese P, Esmon NL, et al. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood. 2011;118(7):1952–1961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu J, Zhang X, Pelayo R, Monestier M, Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, et al. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med. 2009;15(11):1318–1321. doi: 10.1038/nm.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrams ST, Zhang N, Manson J, Liu T, Dart C, Baluwa F, et al. Circulating histones are mediators of trauma-associated lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(2):160–169. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1037OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alhamdi Y, Abrams ST, Cheng Z, Jing S, Su D, Liu Z, et al. Circulating Histones Are Major Mediators of Cardiac Injury in Patients With Sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(10):2094–2103. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito T, Nakahara M, Masuda Y, Ono S, Yamada S, Ishikura H, et al. Circulating histone H3 levels are increased in septic mice in a neutrophil-dependent manner: preclinical evaluation of a novel sandwich ELISA for histone H3. J Intensive Care. 2018;6:79. doi: 10.1186/s40560-018-0348-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokoyama Y, Ito T, Yasuda T, Furubeppu H, Kamikokuryo C, Yamada S, et al. Circulating histone H3 levels in septic patients are associated with coagulopathy, multiple organ failure, and death: a single-center observational study. Thromb J. 2019;17:1. doi: 10.1186/s12959-018-0190-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishida O, Ogura H, Egi M, Fujishima S, Hayashi Y, Iba T, et al. The Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2016 (J-SSCG 2016) J Intensive Care. 2018;6:7. doi: 10.1186/s40560-017-0270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Claushuis TA, van Vught LA, Scicluna BP, Wiewel MA, Klein Klouwenberg PM, Hoogendijk AJ, et al. Thrombocytopenia is associated with a dysregulated host response in critically ill sepsis patients. Blood. 2016;127(24):3062–3072. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-680744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toh JM, Ken-Dror G, Downey C, Abrams ST. The clinical utility of fibrin-related biomarkers in sepsis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24(8):839–843. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e3283646659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh TS, Stanworth SJ, Prescott RJ, Lee RJ, Watson DM, Wyncoll D. Prevalence, management, and outcomes of critically ill patients with prothrombin time prolongation in United Kingdom intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(10):1939–1946. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181eb9d2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogura H, Gando S, Iba T, Eguchi Y, Ohtomo Y, Okamoto K, et al. SIRS-associated coagulopathy and organ dysfunction in critically ill patients with thrombocytopenia. Shock. 2007;28(4):411–417. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31804f7844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massberg S, Grahl L, von Bruehl ML, Manukyan D, Pfeiler S, Goosmann C, et al. Reciprocal coupling of coagulation and innate immunity via neutrophil serine proteases. Nat Med. 2010;16(8):887–896. doi: 10.1038/nm.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. ROC analyses of platelet counts and serum histone H3 levels for predicting 28-day mortality. Table S1. The new scoring system identified coagulopathy patients with high disease severity.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.