Abstract

Background:

Timely, expeditious and appropriate management of Frontal bone fractures and associated Frontal Sinus (FS) injuries are both crucial as well as challenging. Treatment options vary considerably, depending upon the nature, extent and severity of these injuries as well as operator skill, expertise and experience. In cases of posterior table fractures of the Frontal Sinus, literature reports have in general, propounded direct visualization and exploration of the sinus via a bifrontal craniotomy, followed by sinus cranialization.

Aims and Objectives:

To review the standard protocols of management of Frontal bone fractures and Frontal Sinus injuries. To assess the efficacy of a more conservative approach in the management of outer and inner table fractures of the FS.

Materials and Methods:

Contemporary and evolving management protocols and changing treatment paradigms of different types and severities of frontal bone fractures and frontal sinus injuries, have been presented in this case series. A useful Treatment Algorithm has been proposed to efficiently and effectively manage these injuries.

Results:

In the present case series, effective and satisfactory results could be achieved in cases of significantly displaced inner and outer table fractures of the Frontal sinus by a more conservative protocol comprising of open reduction and internal fixation carried out via the existing scar of injury, without having to resort to the more radical intracranial approach and sinus cranialization. Nevertheless, presence of complicating factors such as cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, evidence of meningitis or the development of encephalomeningocoeles necessitated the standard protocol of sinus exploration and its cranialization or obliteration.

Conclusion:

Management protocols of Frontal Sinus injuries vary, based on aspects such as the timing of presentation and intervention, degree of injury sustained, concomitant associated Craniomaxillofacial injuries present, presence of complicating factors or Secondary/Residual deformities & Functional debility, and need to be decided upon on a case to case basis.

Keywords: Anterior and posterior table fractures of frontal sinus, frontal bone, frontal sinus cranialization, frontal sinus obliteration, frontal sinus, nasofrontal duct, nasofrontal outflow tract, onlay grafting

INTRODUCTION

Fractures of the frontal bone with associated involvement of the frontal sinuses (FSs) are relatively uncommon injuries in maxillofacial trauma, comprising just around 5% of all maxillofacial injuries.[1] However, because of their location and close proximity to vital structures such as the orbital and intracranial contents, these injuries can have devastating sequelae if inadequately handled or improperly managed. Further, unaddressed frontal bone fractures with residual defects can leave a patient with disfiguring forehead deformities and prominent contour irregularities.

FS injuries involve fractures of the frontal bone with associated involvement of the FS to varying degrees. These injuries present quite a few challenges to the treating surgeon, and the ideal treatment paradigms have been debated over many years.[2] Also of significance is the fact that as the FS is an air space containing microbial flora, that communicates with the nasal cavity, i.e., the exterior, hence FS fractures are open/compound and are prone to infections which can be potentially life-threatening.[3]

The immediate or acute concerns of frontal bone fractures and FS injuries revolve around:[4]

Protection of the intracranial contents (such as the brain and the meninges)

Protection of the orbital contents

Identification and management of concomitant or associated injuries of the craniomaxillofacial skeleton, if any

Control of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage/rhinorrhea, if any

Prevention of posttraumatic wound infection

Achieving what is known as a “Safe Sinus,” resistant to late complications; and of course

Restoration of an esthetic forehead contour.

The long-term concerns or late complications are issues that can arise or persist 6 months to even decades after the initial injury, such as:[3,5]

Chronic frontal headache due to injury to the supraorbital nerve

Chronic CSF leak

Chronic frontal sinusitis

Mucocele

Mucopyocele

Subdural empyema

Frontal bone osteomyelitis

Meningitis

Brain abscess (due to spread of infection from the FS intracranially via foramina of Breschet)

Residual forehead contour defects and deformities.[6]

Each FS is shaped somewhat like a pyramid, with its base directed medially, forming the intersinus septum. Its “Anterior” or “Outer” table, which forms the brow, forehead, and glabella, is strong and sturdy, with an average thickness of 4 mm, but can reach even up to 12 mm.[7] This, together with the buttressing effect of its pneumatization, confers some degree of protection during trauma and allows it to resist facial fractures more than any other bone in the maxillofacial region. The force needed to fracture the frontal bone is between 800 and 1600 pounds,[2] which is double the force needed to fracture the mandible and five times that needed to fracture the maxilla.

The “Posterior” or “Inner” table is much thinner, just 0.1–4.8 mm in thickness, and it forms part of the anterior cranial fossa. The skull base abutting the posterior aspect of the FS is the cribriform plate of the ethmoid.[8] The floor of the sinus forms the anteromedial portion of the orbital roof and also contains the ostia or opening, through which the FS drains its mucous secretions into the nose, via the nasofrontal outflow tract (NFOT). The sinus is lined by respiratory type of epithelium consisting of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium. The NFOT is an hourglass-shaped structure, which drains secretions from the FS to the frontal recess which continues as the nasofrontal duct (NFD), which opens into the middle meatus of the nasal cavity.

FSs are absent at birth and begin to form only by the age of 2 years. It is believed that this gives toddlers a harder head and protects them from fractures as they learn coordination.[9] The FSs develop as a result of an upward extension of the anterior ethmoidal air cells which pneumatized into the frontal bone and become radiologically evident only at around 8 years of age. Adult size is reached by 12–15 years of age and is usually characterized by two asymmetric sinuses separated by a thin bony septate plate. In the average adult, the FS is 30 mm tall, 25 mm wide, and 19 mm deep. Total volume of both the FSs’ is approximately 10 cm3. Considerable variation exists in the degree of pneumatization, ranging from extreme aeration to nonexistence of one or both of the FSs, which is seen in 5%–15% of the population.[2]

High-velocity and high-energy impacts to the upper third of the face as seen in motor vehicular accidents are the leading cause of FS fractures. This incidence has somewhat reduced with the use of seatbelts and airbags. Other important causes are high impact sports injuries such as martial arts, boxing injuries, interpersonal violence, extreme sports, falls from heights, and penetrating trauma from industrial accidents.[10] Due to the large quantum of forces involved, frontal bone fractures are often associated with other intracranial, ophthalmological and maxillofacial injuries.[2]

Skull base injuries

Intracranial injuries

Pneumocephalus 26%

Cerebral contusion 18%

Dural tear 14%

Subdural, epidural, and intraparenchymal hematomas.

Ophthalmological injuries

Orbital apex syndrome

Posttraumatic volume discrepancies

Muscle entrapment, diplopia

Retinal detachment, lens displacement, blindness.[12]

Maxillofacial injuries

Panfacial fractures

Nasorbitoethmoid (NOE) complex fractures

Orbital wall fractures

Midface fractures

Zygomatic complex fractures.[13]

FS fractures can be broadly divided into four Categories: isolated anterior table fractures which comprise nearly half of the cases, isolated posterior table fractures which are relatively uncommon, combined anterior and posterior table fractures which are the most commonly seen and are severe injuries, and fractures with involvement of the NFD or NFOT.[14]

Clinical presentation of FS Fractures includes the hallmark forehead lacerations, which may be accompanied by a frontal depression. Periorbital edema and ecchymosis are frequently present. Often, swelling and edema mask the forehead deformity, and the injury becomes apparent only later, after the swelling subsides and edema resolves. Suspicion of a CSF leak or intracranial injury mandates a neurosurgical consultation. Diplopia, decrease in visual acuity, and restriction in ocular movements warrant an ophthalmological consultation as well.[3,14]

Plain radiographs are neither sensitive enough, nor do they provide adequate information needed to make a precise diagnosis of FS fractures and NFOT injuries, and they often result in underdiagnoses. High-resolution, thin-cut (0.5 mm thickness) computed tomographic (CT) scans are essential and the gold standard for diagnosing FS injuries in today's era.[15,16] Axial sections provide information on the presence and degree of displacement of anterior and posterior table fractures; coronal sections help to assess the floor of the sinus and orbital roof; and sagittal reconstructions enhance visualization of the NFOT injuries as well as displacement of the outer and inner tables of the FS. Three-dimensional reformatted images help to visualize external contour deformities of the frontal bone.[17]

Critical factors in determining the most appropriate treatment modality to be employed in such injuries are: location of the fracture, presence and degree of displacement of the fractured fragments, status of the NFOT, degree of injury to the dura mater and brain (CSF leak), the presence of other associated craniomaxillofacial injuries, and how old the injury is, that is, timing of presentation and intervention.[18] FS fractures are often associated with brain injury, most likely owing to the location of the impact of the trauma,[5] and this is an important factor to bear in mind while dealing with them.

This retrospective study elaborates the management of varying severities of frontal bone fractures and the various types of FS injuries, carried out in 15 patients over a period of 3 years [Tables 1, 2 and Figures 1–15].

Table 1.

Clinical and radiographic presentation of craniomaxillofacial trauma cases with frontal bone and frontal sinus injuries, management protocol followed, and results achieved

| Age/sex (years) | Categorization of the frontal bone and FS injury | Mode of injury | Clinical presentation | Radiographic and NCCT findings; associated injuries | Treatment protocol employed and salient features of surgical procedure | Results and postoperative follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23/male | Minimally displaced, Isolated fracture of anterior table of FS, without involvement of NFOT [Figure 1] | Fall from a two-wheeler | Abrasions, contusions, and lacerations on face, edema, and tenderness over forehead region | Minimally displaced fracture of outer table of FS with hemosinus | Conservative management - Observation with no surgical intervention | Nil early/late complications |

| 37/male | Vertical, linear, undisplaced fracture of FS [Figure 2] | RTA | Panfacial injuries, facial edema, contusions, circumorbital ecchymosis, deranged occlusion | Panfacial fractures, including fractured left parasymphysis of mandible, Le Forte 1 fracture of maxilla with midpalatal split, frontal bone fracture | ORIF of fractures of maxilla and mandible. FS fracture managed conservatively with no surgical intervention | Nil early/late complications |

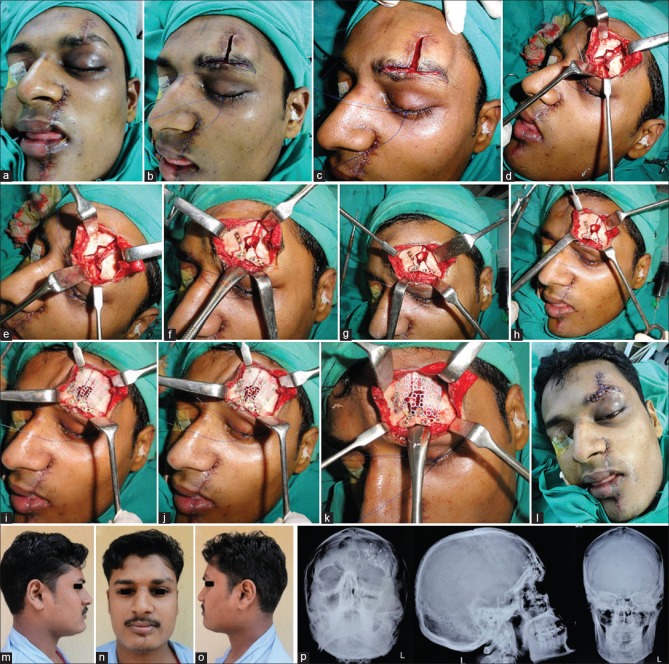

| 29/male | Moderately displaced fracture of frontal bone, involving anterior table of FS [Figure 3] | History of RTA 6 months earlier | Residual deformities, sagging right malar complex, marked hypoglobus and enophthalmos on the right, accompanied by diplopia in all gazes | Moderately displaced fracture of the frontal bone, superior orbital rim, and outer table of the FS, in addition to Le Forte II fracture of the maxilla, and a grossly displaced right zygomatic complex fracture, and a large orbital floor defect (right) | Repositioning of the displaced fractures of the craniomaxillofacial skeleton; ORIF of fractures of maxilla, right superior orbital rim and adjacent frontal bone, inferior orbital rim, and zygomatico-orbito-maxillary complex. Reconstruction of orbital floor defect with symphyseal bone graft | Successful and satisfactory correction of the residual deformities, with nil complications postoperatively |

| 45/male | Moderately displaced comminuted fractures of outer table of FS, without involvement of NFOT | RTA | Hematoma and swelling in the central forehead region | Moderately displaced multiple comminuted fractures of the frontal bone, involving the anterior table alone | ORIF via a bicoronal approach. Holes were carefully drilled through the bone fragments taking care not to injure the inner table. Screws inserted into these holes, and wires were twisted around them which were then grasped with the wire twister and an outward traction applied to reduce the fractures. Once the fragments were reduced, a titanium mesh was used to secure and fix them in place | Good postoperative outcome with no forehead irregularity or deformity and nil complications |

| 53/male | Moderately displaced, linear, horizontal fracture of frontal bone, with disjunction at frontozygomatic sutures bilaterally [Figure 4] | RTA | Facial and forehead edema, ecchymosis and swelling, lacerated wound of the lower lip, deranged occlusion, multiple avulsed, and fractured teeth | Moderately displaced fracture of the frontal bone with disjunctions at the frontozygomatic sutures bilaterally, in association with a left ZMC fracture and comminuted Mandibular body fracture on the left | ORIF of the fractured Frontal bone via a Bi-coronal approach and ORIF of the fractured mandible carried out via the existing laceration. fracture of the zygomatic buttress reduced and fixed via an intraoral upper buccal vestibular approach | Good esthetic and functional results with nil postoperative complications |

| 26/male | Residual deformity comprising of severely displaced fracture of frontal bone (right) without NFOT or FS involvement [Figure 5] | Residual deformity of the craniomaxillofacial region resulting from injuries sustained in a RTA 1 month earlier. Pronounced right antimongoloid slant, with drooping of the entire right zygomatico-orbital complex [Figure 5] | Severely displaced fracture of the frontal bone and zygomatic complex on the right side, with disjunction of the entire segment from the cranium. Fractures of the frontal and temporal bones and also of the right greater wing of sphenoid evident on coronal, axial, and sagittal sections of NCCT [Figure 5] | ORIF of displaced and depressed frontal and temporal bone fragments, including the regions of frontozygomatic and zygomaticotemporal disjunctions [Figure 6]. Shattered right zygomatic buttress, body of zygoma and infraorbital rim reduced, and fixed using titanium minibone plates and screws | Successful repositioning of the displaced and sagging fractured segments of the frontal and zygomatic bones and a good correction of the cosmetic deformity [Figure 7] | |

| 24/male | Severely depressed fracture of anterior table of FS, without involvement of the posterior table or NFOT | Fall down a flight of stairs | Edema and swelling over the glabella region, circumorbital edema and ecchymosis, pig snout deformity caused by severely depressed nasal bridge and a NOE complex fracture | Depressed fracture of the anterior table of the FS, associated with a NOE complex fracture | ORIF of frontal bone and NOE fractures via a bicoronal approach, using titanium microplates and screws | Successful restoration of convex contour of outer table of FS and correction of the pig snout deformity |

| 29/male | Vertical depressed fracture of the frontal bone on the left, with hemosinus of the FS (left), without involvement of NFOT [Figure 8] | Interpersonal violence - Struck on the face with an iron pole | Lacerated wound across the forehead, left eyebrow, and across the face in region of ala of nose, lips, and chin on the left. Fractured anterior teeth | Vertical, depressed fracture of the frontal bone on the left with comminution of the left supraorbital rim, in association with fracture of the left maxilla. Inferiorly displaced segment of the part of the frontal bone forming roof of the left orbit, apparent on coronal and axial sections of NCCT | Repositioning and ORIF of the depressed, comminuted fracture of the frontal bone, and left supraorbital rim, via the existing scar. Removal of crushed, free, nonviable bone fragments. Defect of the frontal bone reconstructed using 3D dynamic titanium mesh implant [Figure 9] | Smooth postoperative recovery with a good esthetic as well as functional outcome and nil postoperative complications [Figure 9] |

| 39/male | Severely comminuted fracture of the outer table of the FS, with hemosinus and involvement of NFOT bilaterally [Figure 10] | RTA | Large lacerated wound across the right side of forehead and eyebrow | Comminuted fracture of the outer table of the FS, with an intact posterior table. Evidence of hemosinus | Removal of free unsalvageable fragments of crushed bone of anterior table of FS. Extirpation of mucosal lining of the entire FS. Packing of the openings of the NFOT and FS obliteration using autologous fat harvested from the subcutaneous layer of patient’s abdominal wall [Figure 10]. Reconstruction of the outer table using 3D dynamic titanium mesh implant [Figure 11] | Successful rendering of a “Safe Sinus” with good restoration of the forehead contour [Figure 11] |

| 48/male | Severely displaced fracture of outer table of FS, with involvement of NFOT | Hockey stick injury (sporting event-related injury) | Swelling and edema over the central forehead region | Severely displaced linear fracture of outer table of FS, with entrapment of mucosal lining of the sinus between edges of fracture. Evidence of hemosinus bilaterally | Raising of an osteoplastic flap around the fracture l line, pedicled on the pericranium. Stripping of entire FS mucosal lining, plugging of NFOT with bone wax, obliteration of the FS using Autologous flap harvested from the anterior abdominal wall, and replacement of the bone flap and fixation of fractures using titanium microplates and screws | Successful rendering of a “Safe Sinus” with nil early/late complications |

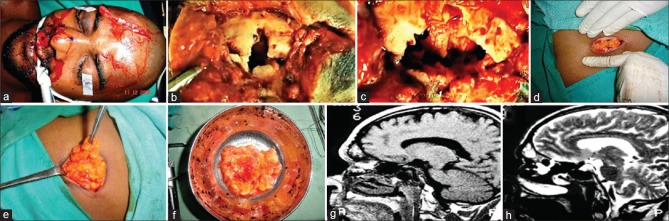

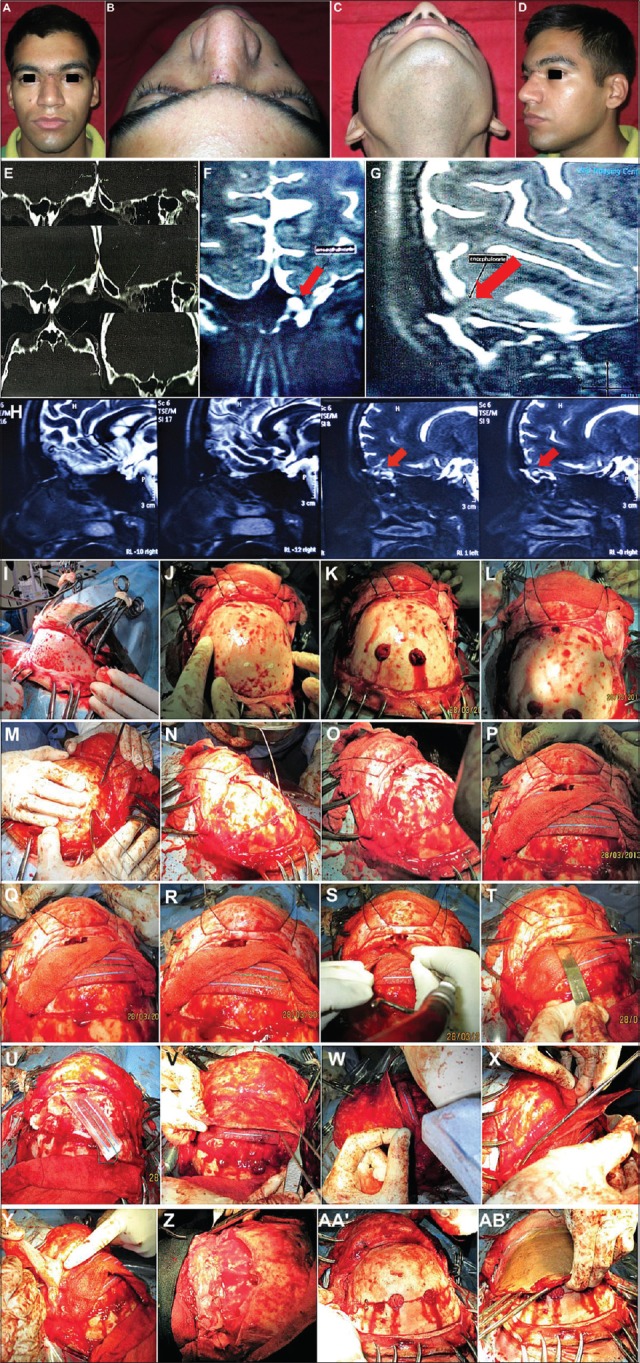

| 20/male | Isolated posterior table fracture, with evidence of pyogenic meningitis and formation of a small encephalomeningocele [Figure 12] | Fall from a horse in a horse-riding accident 6 months earlier | Healed laceration and mild swelling over the glabella region. Recurrent episodes of fever, vomiting, and headaches, isolation of Escherichia coli from the CSF, diagnosed as a case of pyogenic meningitis | Intact anterior table. 4 mm × 5 mm defect in the posterior table of the left FS. MRI cisternography revealed a focal herniation of the straight gyrus of the brain through this defect into the left FS and formation of a small encephalomeningocele [Figure 12] | Bifrontal craniotomy carried out exposing the fractured posterior table of the FS, which was then nibbled away, canalizing the sinus. Sinus mucosa carefully extirpated. Pericranial flap raised by dissecting it off the galea of the bicoronal flap, and used to separate and seal off the intracranial cavity above from the sinonasal tract below. Frontal bone flap replaced and fixed using Titanium microplates and screws | Complete recovery of the patient with no recurrence of the meningitis thereafter |

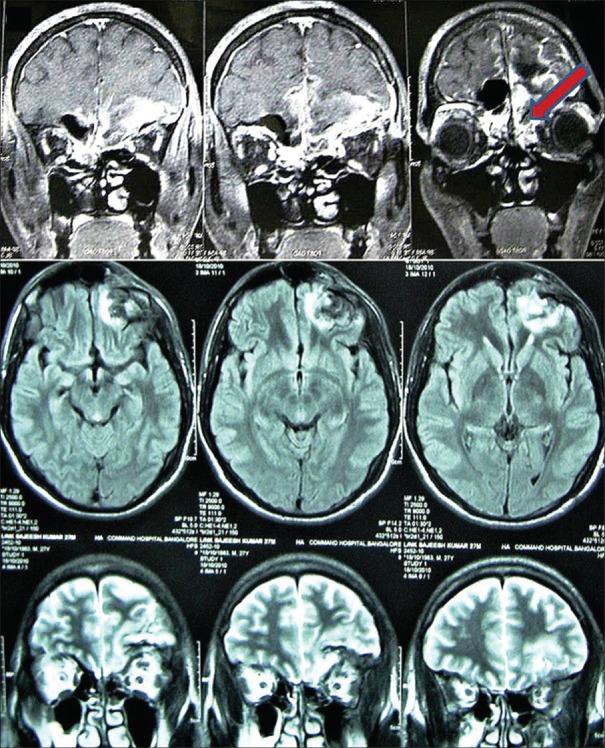

| 27/male | Fracture of frontal bone disrupting both the anterior and posterior tables of the sinus and comminution of the floor of the anterior cranial fossa, with dural tear and CSF leak [Figure 13] | RTA | NCCT revealed comminuted fracture of the frontal bone disrupting both the anterior and posterior tables of the sinus and comminution of the floor of the anterior cranial fossa [Figure 13]. MRI brain showed contusion and herniation of the left frontal lobe through the defect in the posterior table of FS and cranial floor defect [Figure 14] | FS cranialization and dural repair; open reduction and fixation of the fractured anterior cranial floor and reconstruction of the anterior skull base defects, carried out via a bifrontal craniotomy approach [Figure 15]. Sealing off of the intracranial cavity above from the sinonasal tract below achieved using autologous fascia lata graft harvested from the patient’s calf. The graft was also layered over the sinus floor and cranial floor to cover any remaining defects | Smooth, uneventful, and complete recovery of the patient, with nil early/late complications | |

| 22/male | Comminuted fracture of the frontal bone involving both the anterior as well as the posterior tables | RTA | Panfacial fractures; swelling, contusions, and edema of upper and mid-third of face; CSF rhinorrhea | NCCT revealed comminution of both, anterior and posterior tables of the FS. MRI cisternography revealed the exact location of the posterior table defect through which the CSF leak was taking place | Cranialization of the FS and dural repair via a bifrontal craniotomy approach, carried out around the existing fracture lines. The posterior wall of the FS was nibbled away, all the mucosal lining from the anterior wall and floor of the sinus extirpated. The dural breach was identified and repaired. A fascia lata graft was harvested from the calf and was layered over the denuded FS floor separating the nasal and intracranial cavities. A pericranial flap was harvested as well and tucked under the frontal lobes of the brain and sutured to the dura there for an added layer protection. The frontal bone segment was replaced and fixed successful | Successful integration of the FS space with the intracranial space, as evidenced on Postoperative NCCT After 6 months, the patient reported with complication of forehead contour irregularity, due to resorption of smaller fragments of fractured outer table. This was managed by onlay grafting using split-thickness calvarial bone grafts |

| 32/male | Old case of unaddressed depressed fracture of the frontal bone [Figure 15] | RTA 1 year earlier | Forehead contour irregularity with a central depression | Depressed fracture of the frontal bone, involving both anterior and posterior tables of the FS, with evidence of bony union in progress. Surface irregularity and depression in central region of frontal bone | Onlay grafting using Medpore implant, via a bicoronal approach | Successful esthetic outcome with restoration of forehead shape and contour |

| 42/male | Secondary forehead deformity due to residual defect in the frontal bone resulting from an inadequately addressed FS injury | Old case of RTA (2 years ago) | Forehead contour irregularity and deformity with a large depression | Surface defect and depression in central region of frontal bone | Onlay grafting using autologous split-thickness corticocancellous bone graft, harvested from the parietal bone | Successful correction of the forehead contour irregularity with restoration of esthetics |

RTA=Road traffic accident; NCCT=Noncontrast computed tomography; FS=Frontal sinus; NFOT=Nasofrontal outflow tract; ZMC=Zygomaticomaxillary complex; NOE=Naso-orbito-ethmoid; ORIF=Open reduction and rigid internal fixation; CSF=Cerebrospinal fluid; MRI=Magnetic resonance imaging

Table 2.

Treatment algorithm followed and proposed for management of the different types of frontal bone fractures and frontal sinus injuries

| Treatment paradigm depending on type of FS injury | Number of cases | Conservative management (observation) | ORIF | FS obliteration | FS cranialization | Reconstruction/onlay grafting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated anterior table fractures | ||||||

| Undisplaced | 1 | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| Minimally displaced | 1 | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| Moderately/severely displaced | 3 | ✓ | - | - | - | |

| Severely displaced | ||||||

| Without NFOT involvement | 3 | - | ✓ | - | - | - |

| With NFOT involvement | 2 | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Isolated posterior table fractures | ||||||

| Without CSF leak/NFOT involvement | - | ✓(Proposed) | - | - | - | - |

| With CSF leak | 1 | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| With NFOT involvement | - | - | - | - | ✓(Proposed) | - |

| Comminution of posterior table | - | - | - | - | ✓(Proposed) | - |

| Combined anterior and posterior table fractures | ||||||

| Comminution of anterior and posterior tables | 1 | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| Residual deformity from an old inadequately addressed case | 1 | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| 02 | - | - | - | - | ✓ | |

| Total number of cases | 15 |

FS=Frontal sinus; NFOT=Nasofrontal outflow tract; CSF=Cerebrospinal fluid

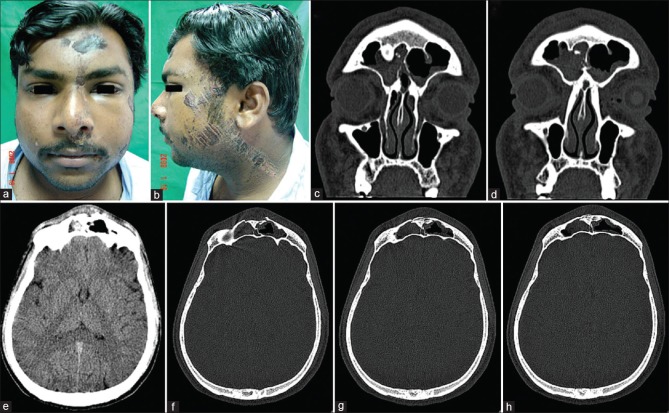

Figure 1.

(a and b) A 23-year-old male patient who sustained multiple abrasions, lacerations, and contusions over the face in a fall from a two-wheeler. (c-h) Noncontrast computed tomography scans (coronal and axial sections) revealed a minimally displaced fracture of the outer table of the frontal sinus with hemosinus. He was managed conservatively and developed no complications

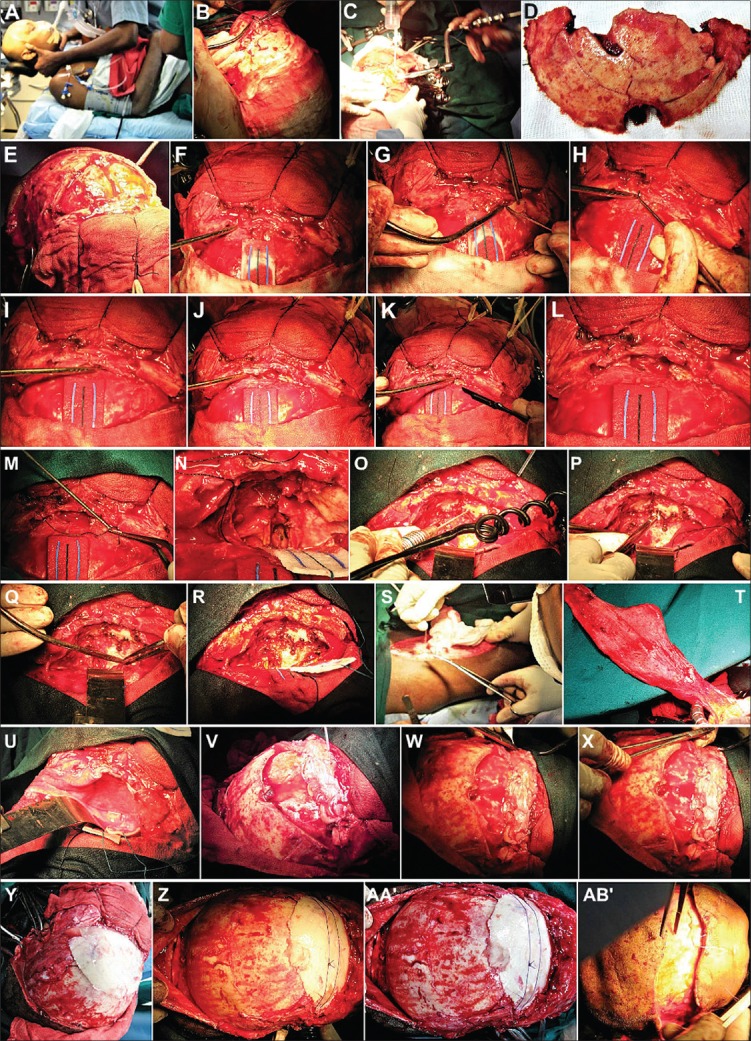

Figure 15.

(A-H) Bifrontal craniotomy. Exposure of fractured floor of the anterior cranial fossa. (I-M) Debridement of free, unsalvageable bone fragments. Remaining bone of posterior table of frontal sinus bone removed, cranializing the frontal sinus. (N-R) Delicate fragments of cranial floor reapproximated, secured, and fixed. (S-V) Fascia lata graft layered over the sinus and cranial floor to separate and seal off the intracranial cavity above from the sinonasal tract below. (W and X) The free flap sutured with the dura. (Y-AB’) Bifrontal bone flap replaced

Figure 2.

(a-d) A 37-year-old male patient sustained panfacial trauma in a road traffic accident. He had fracture of the mandibular parasymphysis, a Le Forte 1 fracture of the right maxilla, and a linear, undisplaced fracture of outer table of the frontal sinus, which was revealed on a computed tomography scan. (e-g) Open reduction and internal fixation of maxilla and mandible carried out, frontal bone fracture was unaddressed. (h-j) Follow-up of 2 years showed no complications arising from the undisplaced frontal bone fracture and no residual forehead deformity or contour irregularity postoperatively

Figure 3.

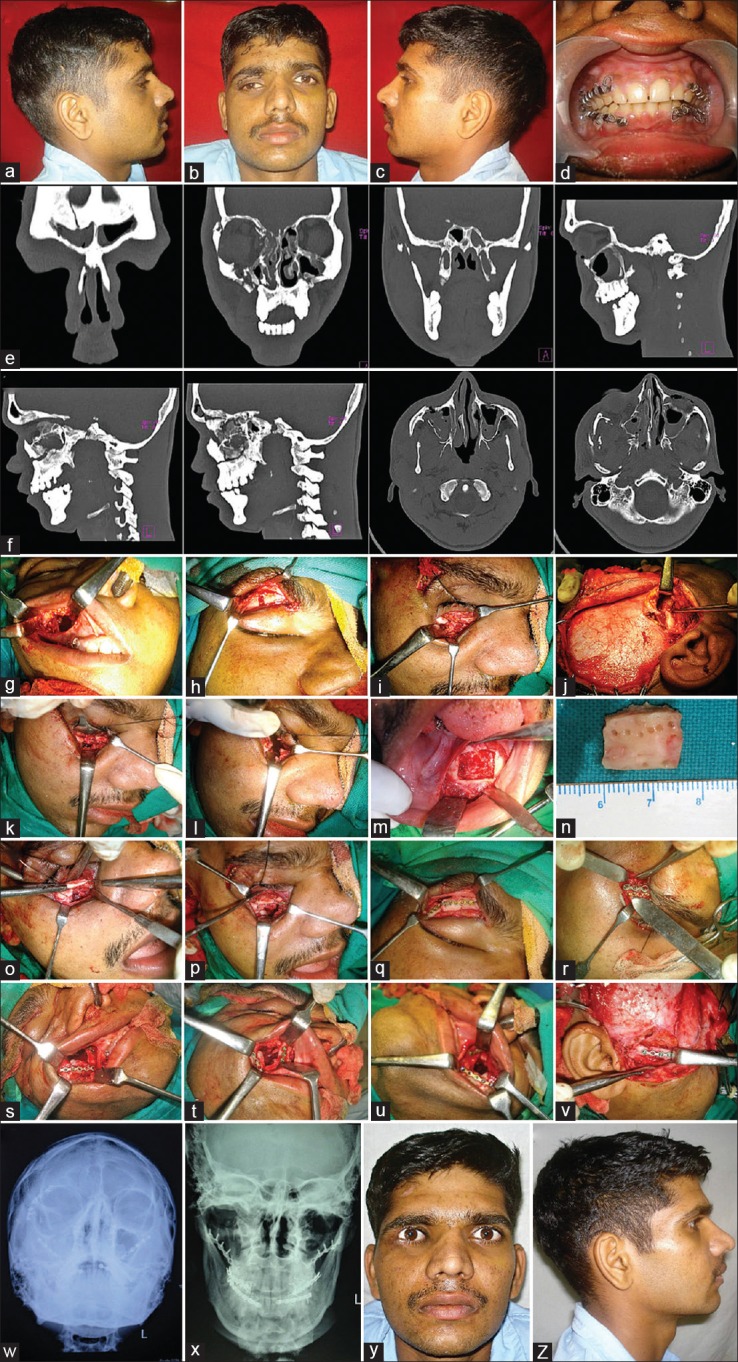

(a-c) A 29-year-old male patient with residual deformities resulting from a road traffic accident 3 months before. Hypoglobus and enophthalmos (right). (d) Arch bar fixation done. (e and f) Moderately displaced fracture of the frontal bone, superior orbital rim, and outer table of the frontal sinus, Le Forte II fracture of maxilla and right zygomaticomaxillary complex, large orbital floor defect (right). (g-j) Fractures exposed. (k-p) Herniated orbital contents restored and floor defect reconstructed using symphyseal bone graft. (q and r) Frontal bone and superior orbital rim fractures reduced and fixed. (s-v) Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures. (w-z) Satisfactory correction of residual deformities

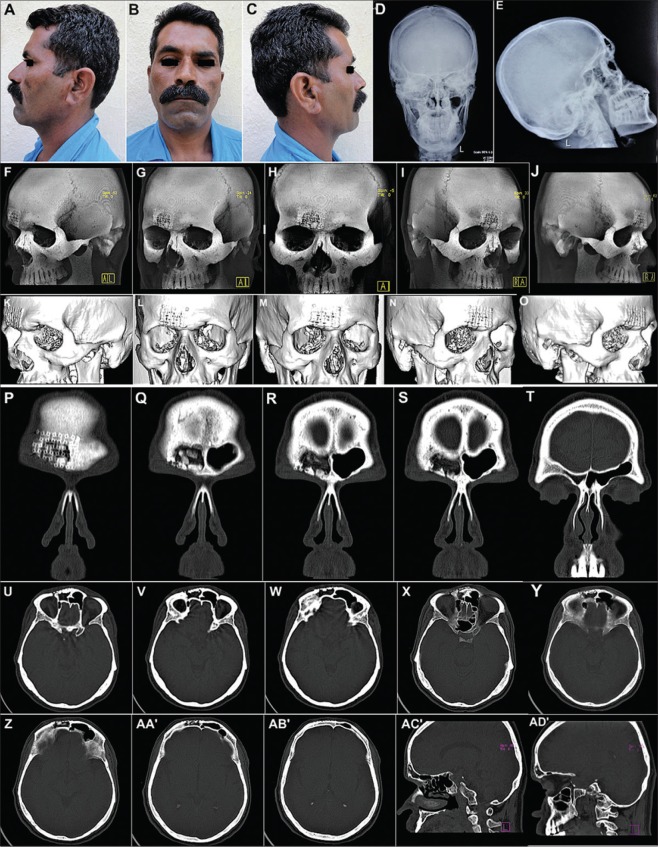

Figure 5.

(a-d) A 26-year-old male patient with residual deformity resulting from a road traffic accident 1 month earlier. The patient was kept under neurological surveillance for a month and thereafter referred for maxillofacial surgical intervention. The patient presented with a distinct antimongoloid slant, drooping of entire right zygomaticomaxillary complex. (e-h) Noncontrast computed tomography scans revealed severely displaced fracture of the frontal bone and right zygomaticomaxillary complex, with disjunction of the entire segment from the cranium. (i-x) Fractures of frontal, temporal bones, and right greater wing of sphenoid evident on coronal, axial, and sagittal sections

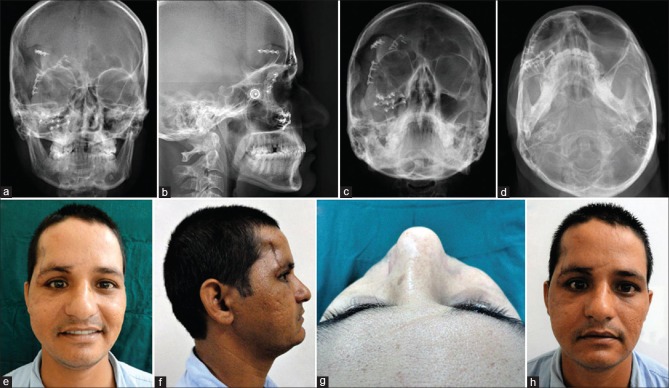

Figure 7.

(a-d) Radiographs postsurgery showing successful repositioning of the displaced fractured segments of the frontal and zygomatic bones with implants in situ. (e-h) Photographs showing a successful correction of the cosmetic deformity and antimongoloid slant caused by the severely displaced and sagging frontal bone and zygomatic complex

Figure 8.

(A-D) A 29-year-old male patient who was struck on the face with a metal pole and presented with a lacerated wound across the forehead, left eyebrow, and across the face in region of ala of nose, lips, and chin on the left. (E-L) Radiographs revealed a vertical depressed fracture of the frontal bone on the left with comminution of the left supraorbital rim and fracture of the left maxilla. (M-AB’) Inferiorly displaced segment of the part of the frontal bone forming roof of the left orbit, apparent on coronal and axial sections of noncontrast computed tomography

Figure 11.

(a-e) Postoperative appearance and plain radiographs of the patient showing a good restoration of the forehead contour. (f-o) Non-contrast computed tomography showing a good reconstruction of the severely comminuted outer table of the frontal sinus by the three-dimensional dynamic titanium mesh implant. (p-t) Coronal sections showing complete obliteration of the right frontal sinus with the titanium mesh implant in situ. (u-ad’) Axial and Sagittal sections showing good restoration of contour and integrity of the outer table of the FS

DISCUSSION

Isolated fractures of the anterior table of the FS range from linear undisplaced or minimally/moderately displaced fractures to severely displaced and comminuted fractures, depending on the nature and degree of trauma sustained, and the size and degree of pneumatization of the sinus. Linear, undisplaced, or minimally displaced fractures carry little or no risk of cosmetic deformity, CSF leak, functional deficit of the FS, or development of a mucocele and hence can be managed conservatively by periodic observation.[19]

If the degree of displacement, as visualized on axial or sagittal sections of CT scans, is >1–2 mm, that is, more than a table's width, it warrants an open reduction and fixation within 7–10 days, not only to correct the contour irregularity, but also to release any mucosal entrapment at the edges of the fracture, which could otherwise lead to late mucocele formation or chronic frontal sinusitis.[20]

More severe injuries resulting in comminution of the outer table require meticulous repositioning, stabilization, and fixation of the fragments in order to prevent a cosmetic contour deformity later. Mucosal injury of the FS would require complete extirpation of the sinus lining and FS obliteration. Presence of a bone defect would entail bone grafting, ideally, split-thickness corticocancellous, or symphyseal bone grafting. Alloplasts such as 3D dynamic titanium mesh or Medpore implants can also be used to bridge small bony defects.[15,21] Titanium mesh, being biologically inert, is an ideal alloplastic material for use in the compound fractures of this region. Its malleable and pliable nature makes it easy to handle, manipulate, and mold to the desired shape and contour intraoperatively and helps to provide a smooth and even contour at the relatively challenging frontal and forehead region, where it lies directly beneath the delicate forehead skin.[15]

Exposure of and access to the fractured fragments of the frontal bone can be gained either through an existing laceration [Figures 6, 9 and 10] or local incisions such as the “brow” or a “Gullwing” or “Open Sky” incisions; however, the scar is unesthetic. Bicoronal incisions are preferable as they provide good access and exposure [Figures 4, 12, 15 and 16] and also are subsequently well camouflaged by hair. There are several techniques to reduce displaced fragments of the fractured frontal bone. A Periosteal elevator or a Bone hook can be insinuated within a fracture line and the fragment mobilized and elevated.[22] A hole can be drilled through a depressed fragment and a screw inserted, which can be grasped using a wire twister to exert an outward traction [Figure 4], thereby reducing a depressed fracture segment. Alternatively, individual fragments can be removed, carried to the back table, where they can be assembled, and then replaced back over the defect. When this is done, the mucosal lining from the inner surface should be removed thoroughly to prevent a later formation of a mucocele, which has the tendency to enlarge progressively, eroding adjacent bone. Titanium microplates or mesh are ideal materials to secure and stabilize the repositioned fracture fragments.[23]

Figure 6.

(a-e) Open reduction and internal fixation under general anesthesia. (f-i) The existing scar above the right eyebrow was used to expose the fractured, displaced, and depressed frontal and temporal bone fragments, including the regions of frontozygomatic and zygomaticotemporal dysjunctions. (j-l) Shattered right zygomatic buttress, body of zygoma, and infraorbital rim reduced and fixed. (m-q) The fractured fragments of the frontal and temporal bones carefully reduced, reapproximated, and fixed with titanium plates and screws. (r-t) Closure was completed in layers after placement of a vacuum-assisted closed suction drain

Figure 9.

(a-d) Existing scar used to expose fracture of the frontal bone and left supraorbital rim. (e-h) Displaced fragments reapproximated, repositioned, and fixed. Unsalvageable free fragments of crushed bone removed. (i-l) Defect of the frontal bone reconstructed using three-dimensional dynamic titanium mesh implant, followed by layer-wise closure. (m-o) Smooth postoperative recovery with a good esthetic as well as functional outcome. (p) Postoperative radiographs showing restoration of the displaced frontal bone and orbital roof and rim fractures with implants in situ

Figure 10.

(a) Severely comminuted fracture of the outer table of the frontal sinus sustained by a 39-year-old male patient in a road traffic accident. (b) Existing laceration used to expose the fracture. (c) Free unsalvageable fragments of bone removed and Mucosal lining of the entire frontal sinus carefully extirpated. (d-f) Autologous fat harvested from the subcutaneous layer of the anterior abdominal wall and used to obturate, obliterate, and seal the frontal sinus, prior to replacement of the outer table augmented with titanium mesh. (g and h) Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging showing the healthy and viable fat tissue within the frontal sinus

Figure 4.

(a-g) A 53-year-old male patient who sustained panfacial trauma in a road traffic accident. Moderately displaced fracture of the frontal bone with disjunctions at the frontozygomatic sutures, fracture left zygomaticomaxillary complex and mandibular body. (h-j) Open reduction and internal fixation of frontal bone via a bicoronal approach. Single screw placed through the anterior table bone to reduce and reposition the depressed fractured frontal bone fragments and stabilize them while rigid fixation was applied using titanium microplates and screws. (k and l) Good esthetic and functional results with nil postoperative complications

Figure 12.

A 20-year-old male patient with isolated posterior table fracture (A-D) sustained in a horse-riding accident, initially managed conservatively. After 6 months developed recurrent episodes of fever, vomiting and headaches. (E-H) Computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging cisternography revealed a 4 mm × 5 mm defect in frontal sinus posterior table and formation of an encephalomeningocoele. (I-Q) Bifrontal craniotomy exposing the frontal lobes and interior of the frontal sinus. (R-U) Frontal sinus cranialization carried out. (V-Z) Pericranial flap draped over denuded sinus floor, tucked beneath the frontal lobes, and sutured to dura. (AA’ and AB’) Bone flap replaced

Figure 16.

(a and b) A 32-year-old male patient, an old case of unaddressed depressed fracture of the bifrontal region, reported a year later for correction of a residual deformity of the forehead region. (c-e) Onlay grafting using Medpore implant was carried out to correct the contour irregularity with a satisfactory esthetic outcome

Riedel's procedure first described in 1898 is an ablative procedure employed for severely displaced and comminuted fractures of the anterior table, which involves exteriorization of the FS by removal of its entire anterior table, allowing the skin of the forehead to directly overly the posterior table. An obvious disadvantage of this procedure is the marked resulting cosmetic defect and forehead deformity.

Osteoplastic flap procedure, first described by Bergera in 1951, is a method to explore the FS by removing its outer table,[24] which is hinged to an inferiorly based pedicle of pericranium. The flap with its pedicle is replaced at the end of the procedure, thus ensuring an esthetic result.

FS injuries with nasofrontal outflow tract involvement

The FS is lined with respiratory type of epithelium, that is, pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium, which propels a physiologically important bilaminar mucous blanket toward naturally draining ostia. The NFOT or NFD, is an hourglass-shaped structure, located posteromedially, one in each of the two FSs. It is the only drainage pathway draining mucous secretions from the FS to the frontal recess, and thereafter, into the middle meatus of the nasal cavity. Under normal circumstances, the NFOT is widely patent. However, following trauma, fractures involving the floor or posterior wall of the FS can cause its narrowing or obstruction, which can result in disruption of the mucociliary clearance system, causing sludging, stasis, and buildup of mucosal secretions within the FS.[25] Failure of aeration and drainage of the FS can lead to edema and inflammation of its mucosal lining which in turn can have several undesirable sequelae like a retrograde spread of infection from the nasal cavity resulting in a chronic frontal sinusitis, mucocele formation, enlargement with bony erosion, which can even get infected leading to mucopyoceles, empyema, brain abscess, and even osteomyelitis.

NFOT injuries are difficult to visualize, detect, and diagnose even on CT scans. In addition to the standard axial and coronal CT images, sagittal reconstruction of the paranasal sinuses can enhance visualization of the NFOT and detect changes in the normal ventilation and drainage of the FS's. NOE complex fractures, anterior skull base injuries near the junction of the posterior table and cribriform plate of ethmoid, fractures involving the floor of the FS, depressed or inferiorly located fractures of the posterior table of the FS, etc., are strongly suggestive of the possibility of NFOT injuries.

NFD injury should be suspected in the presence of sinus opacity or an air-fluid level within the FS persisting for more than 7–10 days following the trauma/injury. A unilateral air-fluid level indicates patency of the contralateral NFD.[26] Removal of the intersinus septum (Intersinus septectomy), using the osteoplastic flap approach, the so-called “Lothrop procedure,” or via an enlarged trephination port, may allow for both the FSs to drain into the unobstructed duct. When disruption of both the NFDs is evident upon exploration or suspected due to persistent bilateral air-fluid levels, complete FS Obliteration is the treatment of choice.[19]

NFD reconstruction procedures using mucoperiosteal flaps such as Samwell Boyden flaps or surgical enlargement of the FS ostium and recess in an attempt to restore and maintain its patency, and endoscopic dilatation of NFD with stents have not gained much popularity because of a high failure rate resulting from scar formation and stenosis. Endoscopic frontal sinusotomy for NFOT recanalization too is prone to failure.[27]

There are several techniques of management of these injuries, but the most recommended and reliable treatment option is FS exclusion either by its obliteration or cranialization.[28,29]

One method of ablating or obliterating the FS is by lifting its anterior table, removing all of its mucosal lining and packing/plugging it with an inert material which seals it off from the nasal cavity, essentially eliminating the sinus as a functional unit [Figure 10]. The anterior table is then replaced.[30] A variety of different alloplasts and autografts have been used over the years to obliterate the sinus, autografts such as pericranium, adipose tissue, temporalis fascia, bone chips, lyophilized cartilage, and alloplasts such as oxidized cellulose, gelfoam, hydroxyapatite cement, methyl methacrylate, bioglass, and calcium sulfate.[31,32]

Isolated posterior table fractures are relatively uncommon, but they are more serious than anterior table fractures as they are often associated with dural tear and CSF leak and because they create a communication between the intracranial cavity and the nasal cavity, allowing for a retrograde spread of infection to the cranial contents which can result in meningitis, brain abscess, etc., [Figure 12]. Hence, the ultimate goal of management is to seal off this communication, which may entail elimination/exclusion of the FS as a functional unit either by sinus obliteration or cranialization.[2]

Management of isolated posterior table fractures is extremely controversial, with some studies recommending surgical exploration of all posterior table fractures no matter how slight, and other studies recommending a conservative approach with just observation, no matter how displaced. The present consensus is that treatment must be guided and dictated by the presence or absence of CSF rhinorrhea and the degree of displacement of the fractured fragments.[21]

Nondisplaced or minimally displaced fractures are less likely to be associated with complications such as dural tear, CSF leak, meningitis or mucocele formation and hence warrant a conservative approach. When CSF leak accompanies a minimally displaced posterior table fracture, an initial conservative approach by observation for 5–7 days with administration of intravenous antibiotics, bed rest, head elevation, and if indicated, lumbar drainage at 10cc/h may be employed. If there is spontaneous resolution of the CSF leak, no further treatment is necessary. However, if there is a persistent CSF leak beyond 8–10 days, FS obliteration via either osteoplastic flap approach or bifrontal craniotomy is indicated.[32] Posterior table repair using grafts is possible, but cumbersome.

When disruption of the posterior table is more than 25%, and there is associated dural tear and CSF leak, cranialization of the sinus with dural repair is indicated. The procedure was first described in 1978 by Donald and Bernstein and involved stripping the sinus of all mucosa and plugging the NFDs and removing the posterior table.[33] Cranialization is a surgical procedure in which communication between the frontal air sinus and the outside space is cutoff, and the air sinus space is integrated with the intracranial space [Figure 12]. In this procedure, the anterior table is osteotomized and lifted away, the entire mucosal lining of the sinus is extirpated, the posterior table bone is nibbled away using rongeurs, the damaged dura is repaired, the NFOT is plugged and sealed off using a pericranial flap, and the anterior table bone is then replaced.[33] The brain is thus allowed to expand into the cranialized sinus, which has now become part of the anterior cranial fossa and the frontal lobes now rest directly against the anterior table.

Combined anterior and posterior table fractures are the most common FS fractures, accounting for more than half of them [Figures 13 and 14]. As they are severe injuries resulting from high-velocity impacts or penetrating trauma, they carry a higher mortality rate as well.[34] They are also often associated with other maxillofacial injuries such as NOE complex fractures, Le Forte III fractures of the Maxilla, orbital injuries, and disruption of the nasofrontal recess. The treatment paradigms revolve around the basic principles already discussed, with cranialization of the FS the treatment of choice for the more severe and extensive fractures involving both tables[35] [Figure 15]. Concomitant management of the associated craniomaxillofacial injuries needs to be carried out as well.

Figure 13.

(a-c) A 27-year-old male patient who sustained severe injuries to the upper third of his face in a road traffic accident and presented with cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. (d-k) Noncontrast computed tomography craniomaxillofacial region revealed comminuted fracture of the frontal bone disrupting both the anterior and posterior tables of the sinus and comminution of the floor of the anterior cranial fossa (as depicted by the red arrows)

Figure 14.

Magnetic resonance imaging brain showed dural tear, contusion, and herniation of the left frontal lobe through the defects in the posterior table of the frontal sinus and floor of the anterior cranial fossa

Late repair of frontal defects and residual deformities

Unaddressed or inadequately managed FS injuries can result in secondary deformities. Even with good planning and meticulous intraoperative technique, a poor frontal contour or frank frontal deformity may occur.

The ideal and preferred method of esthetic reconstruction of a residual defect is by onlay grafting using autogenous grafts. Split-thickness corticocancellous calvarial grafts are the gold standard and the most reliable in the correction of secondary deformities.[36] A variety of alloplastic materials have been used as well to reconstruct larger defects.[37] Dynamic titanium mesh implants can be used either alone or to supplement autografts.[38] Medpore implants have been successfully used for fairly large defects [Figure 16]. Acrylic resin (methyl methacrylate) plates have been widely used in the past,[39] but they are not very popular anymore, owing to various shortcomings such as their exothermic reaction during mixing and setting, leaching out of monomer and the increased risk of delayed infection.[40] Reconstruction of defects should ideally be delayed for at least 18 months to avoid complications.

CONCLUSION

Contemporary treatment paradigms center around early, aggressive, and definitive management of frontal bone fractures and FS injuries, with the goal to protect intracranial structures from further injury, to restore FS function and to minimize the possibility of development of complications in the future. Previously unaddressed frontal bone injuries and defects may also need correction of ensuing secondary/residual deformities in order to restore forehead contour. A multidisciplinary team approach involving both a neurosurgeon as well as a maxillofacial surgeon is often necessary to effectively deal with these injuries.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Erdmann D, Follmar KE, Debruijn M, Bruno AD, Jung SH, Edelman D, et al. A retrospective analysis of facial fracture etiologies. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60:398–403. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318133a87b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strong EB, Pahlavan N, Saito D. Frontal sinus fractures: A 28-year retrospective review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:774–9. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Persistent posttraumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:e1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2000.9.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Khatib K, Danino A, Malka G. The frontal sinus: A culprit or a victim? A review of 40 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:314–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salentijn EG, Peerdeman SM, Boffano P, van den Bergh B, Forouzanfar T. A ten-year analysis of the traumatic maxillofacial and brain injury patient in Amsterdam: Incidence and aetiology. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42:705–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzinger SE, Metzinger RC. Complications of frontal sinus fractures. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2009;2:27–34. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doonquah L, Brown P, Mullings W. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012;24:265–74, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klotch DW. Frontal sinus fractures: Anterior skull base. Facial Plast Surg. 2000;16:127–34. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-12574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farke AA. Evolution and functional morphology of the frontal sinuses in Bovidae (Mammalia: Artiodactyla), and implications for the evolution of cranial pneumaticity. Zool J Linnean Soc. 2010;135:988–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maladière E, Bado F, Meningaud JP, Guilbert F, Bertrand JC. Aetiology and incidence of facial fractures sustained during sports: A prospective study of 140 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30:291–5. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rice DH. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: Diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:19–22. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Follmar KE, Debruijn M, Baccarani A, Bruno AD, Mukundan S, Erdmann D, et al. Concomitant injuries in patients with panfacial fractures. J Trauma. 2007;63:831–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181492f41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manolidis S. Frontal sinus injuries: Associated injuries and surgical management of 93 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:882–91. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez ED, Stanwix MG, Nam AJ, St Hilaire H, Simmons OP, Christy MR, et al. Twenty-six-year experience treating frontal sinus fractures: A novel algorithm based on anatomical fracture pattern and failure of conventional techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1850–66. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818d58ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zavattero E, Boffano P, Bianchi FA, Bosco GF, Berrone S. The use of titanium mesh for the reconstruction of defects of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:690–1. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318280184d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravindra VM, Neil JA, Shah LM, Schmidt RH, Bisson EF. Surgical management of traumatic frontal sinus fractures: Case series from a single institution and literature review. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:141. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.163449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanwix MG, Nam AJ, Manson PN, Mirvis S, Rodriguez ED. Critical computed tomographic diagnostic criteria for frontal sinus fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2714–22. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell RB, Dierks EJ, Brar P, Potter JK, Potter BE. A protocol for the management of frontal sinus fractures emphasizing sinus preservation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:825–39. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice DH. Management of frontal sinus fractures. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:46–8. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200402000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang K, Song YB. Closed reduction of fractured anterior wall of the frontal bone. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:120–2. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200501000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen KT, Chen CT, Mardini S, Tsay PK, Chen YR. Frontal sinus fractures: A treatment algorithm and assessment of outcomes based on 78 clinical cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:457–68. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000227738.42077.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Echo A, Troy JS, Hollier LH., Jr Frontal sinus fractures. Semin Plast Surg. 2010;24:375–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1269766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dayashankara Rao JK, Malhotra V, Batra RS, Kukreja A. Esthetic correction of depressed frontal bone fracture. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2011;2:69–72. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.85858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rains BM., 3rd Frontal sinus stenting. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2001;34:101–10. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohrich RJ, Hollier L. The role of the nasofrontal duct in frontal sinus fracture management. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma. 1996;2:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metzinger SE, Guerra AB, Garcia RE. Frontal sinus fractures: Management guidelines. Facial Plast Surg. 2005;21:199–206. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-922860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soyka MB, Annen A, Holzmann D. Where endoscopy fails: Indications and experience with the frontal sinus fat obliteration. Rhinology. 2009;47:136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oztürk K, Duran M, Arbaǧ H, Keleş B, Kara M, Uyar Y. Frontal sinus obliteration with pericranial-subgaleal flap. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2010;20:13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber R, Draf W, Keerl R, Kahle G, Schinzel S, Thomann S, et al. Osteoplastic frontal sinus surgery with fat obliteration: Technique and long-term results using magnetic resonance imaging in 82 operations. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1037–44. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200006000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fattahi T, Johnson C, Steinberg B. Comparison of 2 preferred methods used for frontal sinus obliteration. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:487–91. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parhiscar A, Har-El G. Frontal sinus obliteration with the pericranial flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:304–7. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.113662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber R, Draf W, Keerl R, Kahle G, Kind M, Schinzel S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging following fat obliteration of the frontal sinus. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:52–8. doi: 10.1007/s002340100635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donath A, Sindwani R. Frontal sinus cranialization using the pericranial flap: An added layer of protection. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1585–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000232514.31101.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tedaldi M, Ramieri V, Foresta E, Cascone P, Iannetti G. Experience in the management of frontal sinus fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:208–10. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181cfe87a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cole P, Kaufman Y, Momoh A, Janz B, Hatef DA, Bullocks J, et al. Techniques in frontal sinus fracture repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1578–9. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a20733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman CD, Costantino PD, Synderman CH, Chow LC, Takagi S. Reconstruction of the frontal sinus and frontofacial skeleton with hydroxyapatite cement. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2000;2:124–9. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.2.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lakhani RS, Shibuya TY, Mathog RH, Marks SC, Burgio DL, Yoo GH, et al. Titanium mesh repair of the severely comminuted frontal sinus fracture. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:665–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marbacher S, Andres RH, Fathi AR, Fandino J. Primary reconstruction of open depressed skull fractures with titanium mesh. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:490–5. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181534ae8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdulai A, Iddrissu M, Dakurah T. Cranioplasty using polymethyl methacrylate implant constructed from an alginate impression and wax elimination technique. Ghana Med J. 2006;40:18–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen TM, Wang HJ, Chen SL, Lin FH. Reconstruction of post-traumatic frontal-bone depression using hydroxyapatite cement. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52:303–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000105522.32658.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]