Abstract

Background:

The extraction of tooth being the most common procedure in oral surgery should be pain free with limited dosage and limited needlepricks. Articaine being unique among amide local anesthetics contains a thiophene group, which increases its liposolubility, and an ester group which helps biotransformation in plasma. Because of the high diffusion properties, it can be used as a single buccal infiltration to extract a maxillary tooth.

Aim and Objective:

Objective of the study was to compare the efficacy of single buccal infiltration of 4% articaine with that of 2% lignocaine for maxillary first molar extraction.

Methodology:

A triple blind randomized controlled study was carried on 100 patients of age group 18-60 years who required maxillary first molar extraction, visiting the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery. They were included in the study after obtaining informed consent. Buccal infiltration of 1.8 ml of anesthetic solution was given randomly to 100 patients with appropriate blinding of the cartridges. Objective signs were checked. If any additional injection was given, it was noted as type and number of rescue injection given. Postoperatively VAS score and surgeon's quality of anesthesia was noted. Duration of anesthesia was measured every 5 minutes for 50 minutes from infiltration.

Results:

Out of 50 patients in group A (Articaine), in 44 patients extraction was done without the need of additional injection whereas in group B(Lignocaine), 29 patients require additional infiltration on the palatal side. The VAS score values for group A were also significantly less in comparison with group B. The mean duration of anesthesia for Group A being (71.70 ± 17.82 min) in 44 patients who only received buccal infiltration.

Interpretation and Conclusion:

The efficacy of single buccal injection of articaine is comparable to buccal and palatal injection of lignocaine.

Keywords: Articaine, extraction, infiltration, lignocaine

INTRODUCTION

Extraction of teeth is one of the most common procedures carried out in the field of oral surgery. Reasons for routine tooth extractions have been widely reported in medical literature.[1] Extraction should be pain-free. Intraoperative pain management is of great importance in extraction procedure.

Local anesthesia forms the backbone of pain control techniques in dentistry, and there has been substantial research interest in finding safer and more effective local anesthetics.[2] The history of local anesthesia started in 1859 when cocaine was isolated by Niemann. In 1884, the ophthalmologist Koller was the first, who used cocaine for topical anesthesia in ophthalmological surgery. Lofgren synthesized lidocaine, which was the first “modern” local anesthetic agent since it is an amide-derivate of diethyl amino acetic acid. Lidocaine was marketed in 1948 and is up till now the most commonly used local anesthetic in dentistry worldwide.[3] Articaine hydrochloride was synthesized by Rushing and colleagues in 1969 and first marketed in Germany in 1976. Its use gradually spread, entering North America in Canada in 1983, and the United Kingdom in 1998.[4]

Articaine hydrochloride is an amide local anesthetic, 4-methyl-3 (2 [propylamino] propionamido)-2-thiophenecarboxylic acid, methyl ester hydrochloride. It is unique among amide local anesthetics in that it contains a thiophene group, which increases its liposolubility, and is the only widely used amide local anesthetic that also contains an ester group. The ester group enables articaine to undergo biotransformation in the plasma (hydrolysis by plasma esterase) and in the liver (by hepatic microsomal enzymes).[4] The primary metabolite, articainic acid, is inactive.[5] Articaine and its metabolites are eliminated through the kidneys. Approximately 5%–10% of articaine is excreted unchanged.[6] No differences in toxicity were noted between 4% articaine and lower concentrations.[7,8,9,10,11]

Pain on palatal injection is a very commonly experienced symptom in dentistry. A number of techniques may be used to reduce the discomfort of intraoral injections,[12,13] the application of topical anesthetic being a well-known and frequently used option. Surface anesthesia does allow for atraumatic needle penetration.[14] The density of the palatal soft tissues and their firm adherence to the underlying bone make palatal injection painful. It has been claimed that articaine is able to diffuse through soft and hard tissues more reliably than other local anesthetics and that maxillary buccal infiltration of articaine provides palatal soft-tissue anesthesia, obviating the need for a palatal injection which in many hands, is traumatic.[14,15]

Previous studies have been done on single buccal infiltration of articaine during maxillary premolar extraction and found to be effective.[16] As the maxillary first molar has thick zygomatic buttress bone, so there is a need to evaluate the success of articaine during the first molar extraction.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of single buccal infiltration of 4% articaine in comparison with 2% lignocaine in maxillary first molar extraction.

Aim

This study aims to compare the efficacy of single buccal infiltration of 4% articaine with that of 2% lignocaine in maxillary first molar extraction.

Objectives

To assess the presence or absence of pain in buccal gingiva after single buccal infiltration using the objective method

To assess the presence or absence of pain in palatal gingiva

To record number and type of rescue injections

To record the subjective pain during the procedure using visual analog scale (VAS)

To record the quality of anesthesia as evaluated by the surgeon using standard parameters

To measure the duration of the anesthesia.

METHODOLOGY

Source of data

A triple-blind randomized controlled study was carried on 100 patients of the age group of 18–60 years who required maxillary 1st molar extraction, visiting the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery were included in the study after obtaining informed consent. They were included in the study randomly.

Type of study

This was a triple-blind prospective comparative study.

Duration of study

The duration of the study was December 2015–July 2017.

Criteria for selection of patients for the study

Inclusion criteria

Patients who require maxillary first molar extraction due to appropriate causes (apical periodontitis, dental caries, root stumps, and prior to prosthodontic rehabilitation). Patients are not having any acute periapical infection in relation to maxillary first molar. Patients are in the age group of 18–60 years.

Exclusion criteria

Inadividuals with any previous history of complications associated with local anesthetic administration. The presence of acute infection or swelling. Those with teeth showing mobility. Patients having sickle cell anemia diseases. Pregnant women and lactating mother. Patients were unable to give informed consent.

Materials

SEPTANEST® (Articaine HCl. 4% with Epinephrine 1:100,000 Injection) manufactured by Septodont, France (Marketed by Septodont Healthcare India Pvt. Ltd., Maharashtra)

LIGNOSPAN (Lignocaine HCl. 2% and Epinephrine 1:100,000) dental cartridges manufactured by Septodont, France (Marketed by Septodont Healthcare India Pvt. Ltd., Maharashtra)

Septoject sterile 27-gauge disposable needles manufactured by Septodont, France (Marketed by Septodont Healthcare India Pvt. Ltd., Delhi)

Rescue injections - Lignox 2% Lignocaine HCl. 2% and Epinephrine 1:80,000 manufactured by INDOCO Remedies Gujarat India.

Method of collection of data

Cartridges were blinded by covering the manufacturer sticker with paper and randomly allocating the numbers from 1 to 100 by a separate person other than the investigator

After obtaining the informed consent given in format, and taking intraoral periapical radiograph (to rule out any periapical pathology) each patient was randomly allocated to the study

Buccal infiltration along the long axis in the area between the two buccal roots of molar was given

All injections were accomplished by one person, with slow injection technique (approximately 1 ml/min) and full cartridge (1.8 ml of solution) was deposited submucosally

The objective symptoms in buccal and palatal gingiva were assessed after 5 min, and if the patient complains of pain, then appropriate rescue injections (palatal infiltration and posterior superior alveolar block) were given and mentioned in the case history pro forma

Extraction was performed on each patient using either 4% articaine or 2% lignocaine but in cartridges labeled from 1 to 100 using appropriate blinding procedure. During extraction, the patient was continuously questioned about pain

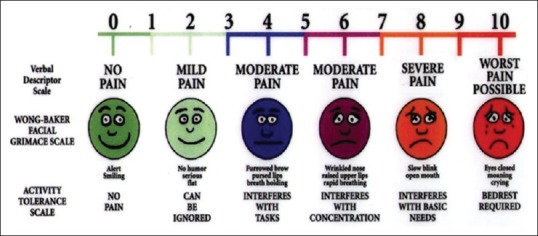

VAS scores (scale given by Wong-Baker) were obtained immediately after the extraction procedure [Figure 1]

Recording of the VAS scores was done by the patient

Following the surgery, the standard postoperative instructions were given to the patients along with the antibiotics and analgesics as and when required

Patients were monitored till the anesthetic effect wears off.

Figure 1.

VAS score measurement scale

Clinical parameters

Instrumentation (objective assessment with the help of sharp end of the periosteal elevator) was done on buccal gingiva as to assess the presence or absence of pain and the results were recorded

Instrumentation (objective assessment with the help of sharp end of the periosteal elevator) was done on palatal gingiva to assess for the presence or absence of pain and the results were recorded

The type and number of rescue injections were recorded

Subjective pain was evaluated using VAS scale The pain evaluation was done by the patient using VAS. The VAS was composed of an unmarked, continuous, horizontal, 100-mm line, anchored by the endpoints of “no pain” on the right and “worst pain” on the left

-

The quality of anesthesia during the surgery as evaluated by the surgeon

This is based on three-point category rating scale:[17]

- 1 = no discomfort reported by the patient during surgery

- 2 = any discomfort reported by the patient during surgery

- 3 = any discomfort reported by the patient during surgery requiring additional anesthesia.

Duration of postoperative anesthesia.

Measured by objective symptoms of pain checked every 5 min for 50 min from infiltration (including the time taken for extraction). Pain on instrumentation was regarded as a sign of wearing off of anesthesia.

All the extraction procedures were performed under 50 min, and if the patient experienced pain interfering with the procedure (moderate pain), an additional injection was given.

RESULTS

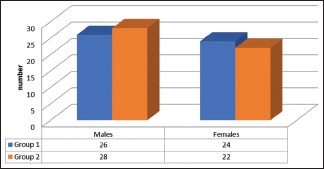

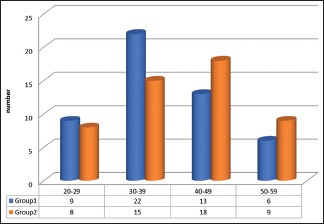

Twenty-six males and 24 females participated in Group A and 28 males and 22 females participated in Group B [Table 1 and Graph 1]. A mean age of 38.2 years in Group A and 38.4 in Group B was found [Table 2 and Graph 2]. All the extractions were simple tooth extractions and bone removal was not required in any of the cases.

Table 1.

Distribution of sex in the group

| Sex | Group A | Group B | %age |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 26 | 28 | 54 |

| Female | 24 | 22 | 46 |

| Total | 50 | 50 | 100 |

Graph 1.

Distribution of sex in the group

Table 2.

Age group distributions in the group

| Age Group (yrs) | 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | Total | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | 9 | 22 | 13 | 6 | 50 | 38.2 |

| Group B | 8 | 15 | 18 | 9 | 50 | 38.4 |

Graph 2.

Age group distributions in the group

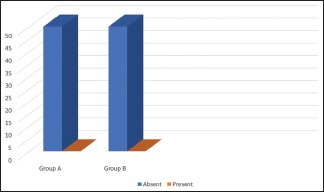

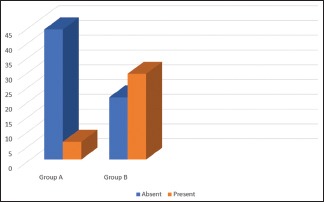

Pain on buccal instrumentation

The pain on buccal instrumentation was measured as present or absent. Group A and Group B showed no statistically significant difference between Group A buccal pain and Group B buccal pain [Table 3 and Graph 3], which indicates both Group A and Group B are equally effective in a reduction in pain.

Table 3.

Pain on buccal instrumentation

| n | Buccal pain | Chi square value | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | ||||

| Group A | 50 | 0 | 50 | Nil | Nil |

| Group B | 50 | 0 | 50 | ||

Graph 3.

Pain on buccal instrumentation

Pain on palatal instrumentation

Table 4 shows Mann–Whitney U-test in between Group A and Group B among the pain on palatal instrumentation, which shows highly statistical significant difference between them (P = 0.001) which indicates palatal pain was less experienced by Group A (Mean rank = 39) compared with Group B (Mean Rank = 62). Graph 4 represents the number of patients having palatal pain present or absent in both Group A and B.

Table 4.

Pain on palatal instrumentation

| n | Frequency of palatal pain | Mean rank | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | ||||

| Group A | 50 | 6 (6%) | 44 (44%) | 39.00 | 0.001 |

| Group B | 50 | 29 (29%) | 21 (21%) | 62.00 | |

Graph 4.

Pain on palatal instrumentation

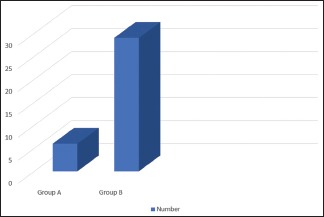

Number of rescue injections

The number of rescue injections used in Group A was 6 and that in Group B was 29 [Table 5 and Graph 5].

Table 5.

Number of rescue injections

| Group A | Group B | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of rescue injections | 6 | 29 |

Graph 5.

Number of rescue injections

Type of rescue injections

The type of rescue injections given in both the groups were single palatal infiltration of 0.5 ml of Lignocaine HCl. 2% with 1:80,000 Epinephrine.

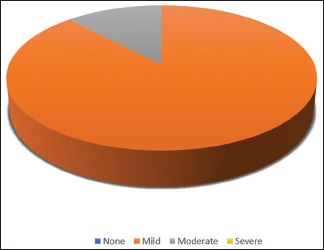

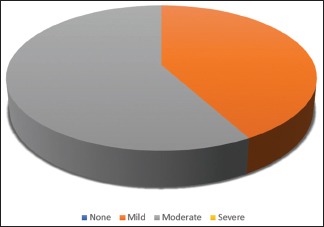

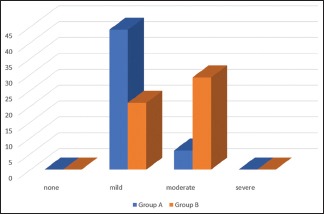

VAS score after extraction

VAS scores after extraction in Group A were: none for 0 patients (0%), mild for 44 patients (88%), moderate for 6 patients (12%), and severe for 0 patients (0%) [Graph 6]. VAS scores after extraction in Group B were: none for 0 patients (0%), mild for 21 patients (42%), moderate for 29 patients (58%), and severe for 0 patients (0%) [Graph 7]. Comparison of both the groups gives a statistically significant result [Tables 6, 7 and Graph 8].

Graph 6.

Visual Analog Scale score in group A

Graph 7.

Visual Analog Scale score in group B

Table 6.

Mann- Whitney test- Visual analog scale score

| Groups | n | Mean rank | Sum of ranks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 50 | 35.23 | 1761.50 |

| Group 2 | 50 | 65.77 | 3288.50 |

| Total | 100 |

Table 7.

P Visual Analog Scale score

| VAS score | |

|---|---|

| Mann- Whitney U | 486.500 |

| Wilcoxon W | 1761.500 |

| Z | -5.516 |

| P | 0.001 |

Graph 8.

Comparison of Visual Analog Scale score in group A and group B

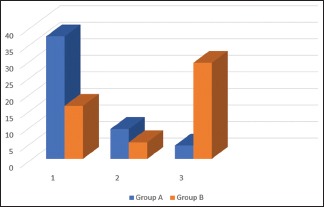

Quality of the anesthesia

There was no statistically significant difference between the quality of anesthesia provided by the local anesthetic agent in both groups [Tables 8, 9 and Graph 9].

Table 8.

Mann-Whitney test-quality of anesthesia

| Groups | n | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 50 | 37.59 | 1879.50 |

| Group 2 | 50 | 63.41 | 3170.50 |

| Total | 100 |

Table 9.

P quality of anesthesia

| Quality of anesthesia | |

|---|---|

| Mann- Whitney U | 604.500 |

| Wilcoxon W | 1879.500 |

| Z | -4.937 |

| P | 0.001 |

Graph 9.

Quality of anesthesia

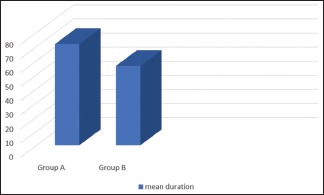

Duration of postoperative anesthesia

The mean duration of postoperative anesthesia in Group A was (71.70 ± 18.01 min) in 44 patients which only received buccal infiltration. In Group B cases, 29 patients had received additional injections, so excluding those cases 21 cases the duration of anesthesia was noted. Of those 21 cases, in 1 case, the anesthetic effect was subsided before 50 min. Rest 20 cases showed the mean duration of about (56.25 ± 6.00 min) [Table 10 and Graph 10].

Table 10.

Duration of anesthesia

| Group | n | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | 44 | 71.70 | 18.01 |

| Group B | 20 | 56.25 | 6.00 |

Graph 10.

Duration of anesthesia

DISCUSSION

Articaine first appeared in German literature in the year 1969 and referred to as carticaine.[4] Being an amide-type local anesthetic, it contains a carboxylic ester group, thus is inactivated in the liver as well as by hydrolyzation in the tissue and the blood. The main metabolic product is articainic acid (or more accurately: Articainic carboxylic acid), which is nontoxic and inactive as a local anesthetic. Articaine has a reputation of providing a good local anesthetic effect.[18] Articaine is administered as a 4% local anesthetic solution. This different concentration of local anesthetic agents is because of the difference in their local anesthetic potency and lipid solubility. Agents with lower lipid solubility coefficients are marketed at higher concentrations than those with higher lipid solubility coefficients. Lipid solubility coefficient for articaine is 40.[19] Equal analgesic efficacy along with lower systemic toxicity (i.e., a wide therapeutic range) allows the use of articaine in higher concentrations than other amide-type local anesthetics.[20] The onset of anesthesia with 4% articaine with epinephrine 1:200,000 is 1.5–1.8 min for maxillary infiltration.[21] Lemay et al.[22] found an average time to onset of anesthesia (as determined by electrical stimulation of the pulp) for both concentrations (1:100,000 concentration and 1:200,000 concentration) with maxillary infiltration to be (105.0 s ± 49.2 scanning electron microscope [SEM] vs. 118.6 s ± 83.6 SEM, respectively). In comparing articaine with lidocaine solutions in maxillary infiltration, Costa et al.[23] found statistically significant faster onset with 4% articaine (1:100,000 and 1:200,000 epinephrine) when compared with 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. However, the onset times of 1.6, 1.4, and 2.8 min for the three solutions had onset differences of around a minute and would not be clinically significant.

In our study, the objective signs were measured 5 min after the injection as time is needed for the diffusion of solution to the palatal side which was in accordance with the study conducted by Srinivasan et al.,[24] and Uckan et al.[12] On the contrary, Kandasamy et al.[25] took a latency time of 10 min to extract the maxillary tooth. A study conducted by Khan and Qazi[26] concluded that all the successful cases for buccal infiltration of 2% lignocaine had achieved palatal anesthesia by 5 min, whereas the study conducted by Kumaresan et al.[27] found out that 8.5–10 min latency period is required to achieve palatal anesthesia in the molar region when only a buccal infiltration of lidocaine local anesthetic solution is administered. In our study, all the individuals were anaesthetized on the buccal side using 4% articaine or 2% lignocaine, after 5 min on the palatal side using objective methods of the assessment of pain only 21 patients were anesthetized whereas rest experienced pain on palatal instrumentation in lignocaine group and 44 patients out of 50 were anesthetized in articaine group. A study conducted by Kandasamy et al.[25] and by Sharma et al.[28] found that 91.38% and 93.75% (n = 80) patients (using VAS scale) in articaine group experienced no pain on palatal instrumentation which were similar to our results whereas on the contrary all the cases for lignocaine group experienced pain which was contrary to our study. Khan and Qazi[26] found that single buccal infiltration of 1.7 ml solution of 2% lignocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine with 5 min of latency shows 28% successes (no pain on palatal instrumentation) and 40% success rate in the posterior maxilla. Sekhar et al.[29] found no statistically significant difference in pain on palatal instrumentation with depositing of 2 ml of 2% lignocaine with 1:80,000 buccally or 1.7 ml buccally and 0.25 ml palatally with latency period of 8 min. Additional 6 (12%) rescue injections were used in Group A and 29 (58%) in Group B which were palatal infiltration of 2% lignocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine. The results for articaine were similar to the study conducted by Luqman et al.[30] which uses additional 16 (16%) rescue injections; however, the solution used was articaine for palatal infiltration. A study conducted by Somuri et al.[15] demonstrated that articaine administered alone as single buccal infiltration provides favorable anesthesia as compared to buccal and palatal injection of lidocaine for extraction of maxillary premolars. Uckan et al.,[12] Srinivasan et al.,[24] and Kandasamy et al.[25] also demonstrated that permanent maxillary teeth can be removed without palatal injection by giving buccal infiltration of articaine. On the contrary, a study conducted by Evans et al.[31] showed that a maxillary infiltration of 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine statistically improved anesthetic success when compared with 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine in the lateral incisor but not in the first molar. Local anesthetic solutions with low pH have been thought to cause a burning sensation and thus more pain than anesthetics with more neutral pH.[32,33] Since articaine has a slightly higher pH (3.5–4), it produces less pain on injection also. When surveying the patients on quality of anesthesia, statistically significant differences were found between the two solutions in our study. Articaine provides better quality of anesthesia. The mean duration of postoperative analgesia with articaine was (71.70 ± 17.82 min) in 44 patients who only received buccal infiltration, results similar to those by Hassan et al.,[16] Darawade et al.,[34] Costa et al.[23] whereas for lignocaine group, the mean duration was about (56.25 ± 5.92 min) for 20 cases who received buccal infiltration only. In one case, the anesthetic effect subsided before 50 min, and in that case, extraction procedure was performed by 20 min. The results were in accordance with study conducted by Darawade et al.[34] The long period of analgesia for articaine finds explanation in a study by Oertel et al.[20] who reported that the concentration of articaine in the alveolus of a tooth after extraction was about 100 times higher than in systemic circulation. Moreover, the long duration of postoperative analgesia evoked by articaine may be explained by its ability to readily diffuse through tissues due to the presence of a thiophene group in the molecule, which increases its liposolubility.[35]

The safety of the use of articaine has been a matter of debate. A study conducted by Hillerup et al.[36] showed the articaine 4% presented with the highest incidence of neurosensory disturbance with mandibular nerve being most commonly affected. High incidence of neurosensory disturbance was seen in solutions with higher concentrations of anesthetic agents. Kämmerer et al.[37] showed local anesthetic effects of 2% articaine are comparable to 4% articaine. In Germany, a 2% formulation in association with 1:200,000 epinephrine has recently become available for dental use, which proved as effective as 4% concentration in teeth extractions with infiltration anesthesia.[35] Hence, the use of a higher concentration of articaine is debatable. One thing should be kept in mind that overreporting of problems is natural when a new drug is introduced to the practice.[38] Malamed et al.[39] conducted a study and found that 4% Articaine with 1:1,00,000 epinephrine is a safe and effective local anesthetic for use in pediatric dentistry. A study done by van Oss et al.[5] found adverse events such as headache, facial edema, infection, gingivitis, and paresthesia. El-Qutob et al.[40] also reported a case of immediate skin reaction with articaine whereas Chisci et al.[41] reported a case of trochlear nerve palsy using 4% articaine during posterior superior alveolar nerve block. In the present study, no signs or symptoms of paresthesia, nervousness, dizziness, tremors, blurred eyes, or any indication of adverse effects on the cardiovascular and central nervous systems in any subject with either articaine or lignocaine were found.

CONCLUSION

This study concluded that:

The pain experienced during the single buccal injection of articaine is significantly less as compared to lignocaine

Efficacy of single buccal injection of articaine is comparable to buccal and palatal injection of lignocaine

Maxillary 1st molars can be extracted by giving only buccal infiltration of articaine thereby obviating the need for the poorly tolerated palatal injection.

The choice of local anesthetic depends on several factors: length of the procedure, need for hemostasis, need for postoperative analgesia and whether any contraindications exist to the administration of the selected local anesthetic. Although lidocaine is considered as the gold standard local anesthetic for most dental procedures, articaine is a good substitute. However, further studies with larger sample size are warranted to substantiate our results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adeyemo WL, Taiwo OA, Oderinu OH, Adeyemi MF, Ladeinde AL, Ogunlewe MO. Oral health-related quality of life following non-surgical (routine) tooth extraction: A pilot study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:427–32. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.107433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malamed SF. 4th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1997. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahn R, Ball B. Local Anesthesia in Dentistry: Articaine and Epinephrine for Dental Anesthesia. Seefeld (Germany): 3M ESPE AG. (1st ed) 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malamed SF, Gagnon S, Leblanc D. Articaine hydrochloride: A study of the safety of a new amide local anesthetic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:177–85. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Oss GE, Vree TB, Baars AM, Termond EF, Booij LH. Pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and renal excretion of articaine and its metabolite articainic acid in patients after epidural administration. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1989;6:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vree TB, Baars AM, van Oss GE, Booij LH. High-performance liquid chromatography and preliminary pharmacokinetics of articaine and its 2-carboxy metabolite in human serum and urine. J Chromatogr. 1988;424:440–4. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winther JE, Nathalang B. Effectivity of a new local analgesic Hoe 40 045. Scand J Dent Res. 1972;80:272–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1972.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winther JE, Patirupanusara B. Evaluation of carticaine – A new local analgesic. Int J Oral Surg. 1974;3:422–7. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(74)80007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raab WH, Muller R, Muller HF. Comparative studies on the anesthetic efficiency of 2% and 4% articaine. Quintessence. 1990;41:1208–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruprecht S, Knoll-Köhler E. A comparative study of equimolar solutions of lidocaine and articaine for anesthesia. A randomized double-blind cross-over study. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 1991;101:1286–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raab WH, Reithmayer K, Müller HF. A procedure for testing local anesthetics. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z. 1990;45:629–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uckan S, Dayangac E, Araz K. Is permanent maxillary tooth removal without palatal injection possible? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:733–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harbert H. Topical ice: A precursor to palatal injections. J Endod. 1989;15:27–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(89)80094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhalla J, Meechan JG, Lawrence HP, Grad HA, Haas DA. Effect of time on clinical efficacy of topical anesthesia. Anesth Prog. 2009;56:36–41. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-56.2.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Somuri AV, Rai AB, Pillai M. Extraction of permanent maxillary teeth by only buccal infiltration of articaine. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2013;12:130–2. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0396-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassan S, Rao BH, Sequeria J, Rai G. Efficacy of 4% articaine hydrochloride and 2% lignocaine hydrochloride in the extraction of maxillary premolars for orthodontic reasons. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2011;1:14–8. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.83145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregorio LV, Giglio FP, Sakai VT, Modena KC, Colombini BL, Calvo AM, et al. A comparison of the clinical anesthetic efficacy of 4% articaine and 0.5% bupivacaine (both with 1:200,000 epinephrine) for lower third molar removal. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claffey E, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M, Weaver J. Anesthetic efficacy of articaine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks in patients with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2004;30:568–71. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000125317.21892.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fonseca RJ. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 2000. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, in Local Anesthetics; pp. 58–77. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oertel R, Rahn R, Kirch W. Clinical pharmacokinetics of articaine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:417–25. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199733060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malamed SF, Gagnon S, Leblanc D. Efficacy of articaine: A new amide local anesthetic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:635–42. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemay H, Albert G, Hélie P, Dufour L, Gagnon P, Payant L, et al. Ultracaine in conventional operative dentistry. J Can Dent Assoc. 1984;50:703–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa CG, Tortamano IP, Rocha RG, Francischone CE, Tortamano N. Onset and duration periods of articaine and lidocaine on maxillary infiltration. Quintessence Int. 2005;36:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srinivasan N, Kavitha M, Loganathan CS, Padmini G. Comparison of anesthetic efficacy of 4% articaine and 2% lidocaine for maxillary buccal infiltration in patients with irreversible pulpitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:133–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kandasamy S, Elangovanb R, Johnb RR, Kumar N. Removal of maxillary teeth with buccal 4% Articaine without using palatal anesthesia – A comparative double blind study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2015;27:154–158. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan SR, Qazi SR. Extraction of maxillary teeth by dental students without palatal infiltration of local anaesthesia: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Dent Educ. 2017;21:e39–e42. doi: 10.1111/eje.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumaresan R, Srinivasan B, Pendayala S. Comparison of the effectiveness of lidocaine in permanent maxillary teeth removal performed with single buccal infiltration versus routine buccal and palatal injection. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14:252–7. doi: 10.1007/s12663-014-0624-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma K, Sharma A, Aseri M, Batta A, Singh V, Pilania D, et al. Maxillary posterior teeth removal without palatal injection -truth or myth: A dilemma for oral surgeons. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZC01–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10378.5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekhar GR, Nagaraju T, KolliGiri, Nandagopal V, Sudheer R, Sravan Is palatal injection mandatory prior to extraction of permanent maxillary tooth: A preliminary study. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:100–2. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.80006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luqman U, Majeed Janjua OS, Ashfaq M, Irfan H, Mushtaq S, Bilal A. Comparison of articaine and lignocaine for uncomplicated maxillary exodontia. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25:181–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans G, Nusstein J, Drum M, Reader A, Beck M. A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of articaine and lidocaine for maxillary infiltrations. J Endod. 2008;34:389–93. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borchard U, Drouin H. Carticaine: Action of the local anesthetic on myelinated nerve fibres. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;62:73–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sumer M, Misir F, Celebi N, Muǧlali M. A comparison of injection pain with articaine with adrenaline, prilocaine with phenylpressin and lidocaine with adrenaline. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E427–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darawade DA, Kumar S, Budhiraja S, Mittal M, Mehta TN. A clinical study of efficacy of 4% articaine hydrochloride versus 2% lignocaine hydrochloride in dentistry. J Int Oral Health. 2014;6:81–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wahl MJ, Schmitt MM, Overton DA, Gordon MK. Injection pain of bupivacaine with epinephrine vs. prilocaine plain. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:1652–6. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hillerup S, Jensen RH, Ersbøll BK. Trigeminal nerve injury associated with injection of local anesthetics: Needle lesion or neurotoxicity? J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:531–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kämmerer PW, Schneider D, Palarie V, Schiegnitz E, Daubländer M. Comparison of anesthetic efficacy of 2 and 4 % articaine in inferior alveolar nerve block for tooth extraction-a double-blinded randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:397–403. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1804-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hintze A, Paessler L. Comparative investigations on the efficacy of articaine 4% (epinephrine 1:200,000) and articaine 2% (epinephrine 1:200,000) in local infiltration anaesthesia in dentistry – A randomised double-blind study. Clin Oral Investig. 2006;10:145–50. doi: 10.1007/s00784-005-0025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malamed SF, Gagnon S, Leblanc D. A comparison between articaine HCl and lidocaine HCl in pediatric dental patients. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El-Qutob D, Morales C, Peláez A. Allergic reaction caused by articaine. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2005;33:115–6. doi: 10.1157/13072924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chisci G, Chisci C, Chisci V, Chisci E. Ocular complications after posterior superior alveolar nerve block: A case of trochlear nerve palsy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42:1562–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]